Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Law of Maintenance

Încărcat de

Kumar Mangalam100%(1)100% au considerat acest document util (1 vot)

226 vizualizări11 paginimaintenance

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentmaintenance

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

100%(1)100% au considerat acest document util (1 vot)

226 vizualizări11 paginiLaw of Maintenance

Încărcat de

Kumar Mangalammaintenance

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 11

Maintenance under Hindu Law

Maintenance under Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956

Maintenance

Maintenance means the right of dependents to obtain food, clothing, shelter, medical care,

education, and reasonable marriage expenses for marriage of a girl, from the provider of the

family or the inheritor of an estate. The basic concept of maintenance originated from the

existence of joint families where every member of the family including legal relations as well

as concubines, illegitimate children, and even slaves were taken care of by the family.

However, maintenance does not mean unreasonable expectations or demands.

Historical Perspective

Joint family system has been a main feature of the Hindu society since vedic ages. In a joint

family, it is the duty of the able male members to earn money and provide for the needs of

other members such as women, children, and aged or infirm parents.

In Manusmriti, it has been said that wife, children, and old parents must be cared for

even by doing a hundred misdeeds.

Since in the social structure of Hindu society the joint family system looms large, the law of

maintenance has a special significance in Hindu law. All members of a joint family, whatever

be their status and whatever be their age, are entitled to maintenance. Hindu law recognizes

that a Hindu has a personal obligation to maintain certain near relations, such as wife,

children, and aged parents and that the one who takes anothers property has an obligation to

maintain the latters dependents. Thus husband has a direct obligation to maintain his wife. In

modern system of law, the obligation exists even after the dissolution of marriage. Thus, a

wife has right to maintenance in following situation:

When the wife lives with her husband.

When the wife lives separate from her husband, and

When the wife lives separate under a decree of the court or when is dissolved.

HAMA 1956 codifies a lot of principles governing the maintenance of dependents of a Hindu

male. Under this act, the obligation can be divided into two categories - personal obligation

and obligation tied to the property.

Dependents based on personal obligation

Personal obligation means that a Hindu is personally liable, irrespective of the property that

he has inherited or his earnings, to provide for certain relations who are dependent on him.

These relations have been specified in the following sections of HAMA 1956.

Section 18(1) declares that whether married before or after this act, a Hindu wife shall be

entitled to claim maintenance by her husband during her lifetime.

Sec 18(2) says that a wife is entitled to live separately without forfeiting her right to claim

maintenance in certain situations.

Sec 18(3) says that a wife shall not be entitled to separate residence and maintenance of she is

unchaste or ceases to be a Hindu.

In the case of Jayanti vs Alamelu, 1904 Madras HC held that the obligation to maintain

one's wife is one's personal obligation and it exists independent of any property, personal or

ancestral.

Section 20(1) declares that a Hindu is bound to maintain his children, legitimate or

illegitimate, and aged or infirm parents. 20(2) says that a child, legitimate or illegitimate, can

claim maintenance from father or mother, until the child is a minor. 20(3) says that the right

to claim maintenance of aged or infirm parents and unmarried daughter extends in so far as

they are not able to maintain themselves through their other sources of income.

In this case, a childless step-mother is also considered a parent.

Dependents based on obligation tied to property

A person has obligation to support certain relations of another person whose property has

devolved on him. In this case, this obligation is not personal but only up to the extent that it

can be maintained from the devolved property.

Section 21 specifies these relations of the deceased who must be supported by the person who

receives the deceased property.

1. father

2. mother

3. widow, so long as she does not remarry

4. son, predeceased son's son, or predeceased son's predeceased son's son until the age of

majority. Provided that he is not able to obtain maintenance from his father or mother's

estate in the case of grandson, and from his father or mother, or father's father or

father's mother, in the case of great grandson.

5. daughter or predeceased son's daughter, or predeceased son's predeceased son's

daughter until she gets married. Provided that he is not able to obtain maintenance from

his father or mother's estate in the case of granddaughter, and from his father or

mother, or father's father or father's mother, in the case of great granddaughter.

6. widowed daughter, if she is not getting enough maintenance from her husband's,

children's, or father in law's estate.

7. widow of predeceased son, or widow of predeceased son's son, so long as she does not

remarry and if the widow is not getting enough maintenance from her husband's,

children's or her father or mother's estate in the case of son's widow.

8. illegitimate son, until the age of majority

9. illegitimate daughter, until she is married.

Section 22 (1) says that heirs of a Hindu are bound to maintain the dependents of the

deceased out of the estate inherited by them from the deceased. Thus, this obligation is to be

fulfilled only from the inherited property and so it is not a personal obligation. 22(2) says that

where a dependent has not received any share, by testamentary or intestate succession, he

shall be entitled to maintenance from those who take the estate. 22(3) says that the liability of

each heir is in proportion to the estate obtained by him. 22(4) says that a person who himself

is a dependent cannot be forced to pay any amount of maintenance if the amount causes his

share to reduce below what is required to maintain himself.

How much maintenance

Section 23(1) says that courts will have complete discretion upon whether and how much to

maintenance should be given. While deciding this, the courts shall consider the guidelines

given in sections 23(2) and 23(3).

Section 23(2) says that that while deciding the maintenance for wife, children, and aged or

infirm parents, the courts will consider:

1. the position and status of the parties.

2. the reasonable wants of the claimants.

3. If a claimant has a separate residence, is it really needed.

4. the value of the estate and the income derived from it or claimant's own earning or any

other source of income.

5. the number of claimants.

Section 23(3) says that while determining the maintenance for all other dependents the courts

shall consider the following points:

1. the net value of the estate after paying all his debts.

2. the provisions, if any, made in the will in favor of the claimants.

3. the degree of the relationship between the two.

4. the reasonable wants of the dependent.

5. the past relations between the deceased and the claimants.

6. claimant's own earnings or other sources of income.

7. the number of dependents claiming under this act.

Separate earning of the claimant

Whether the claimant has separate earning on income is a question of fact and not a question

of presumption. It cannot be, for example, presumed that a college educated girl can maintain

herself.

In the case of Kulbhushan vs. Raj Kumari wife was getting an allowance of 250/- PM from

her father. This was not considered to be her income but only a bounty that she may or may

not get. However, income from inherited property is counted as the claimants earning.

Arrears of Maintenance

In the case of Raghunath vs Dwarkabai 1941 Bom HC held that right of maintenance is a

recurring right and non-payment of maintenance prima facie constitutes proof of wrongful

withholding.

Wife's right to separate residence without forfeiting the right

to maintenance

Section 18(2) says that a wife can live separately and still claim maintenance from husband in

the following situations.

1. Desertion: It the husband is guilty of deserting the wife without her consent, against

wife's wishes, and without any reasonable cause, the wife is entitled to separate

residence. In the case of Meera vs Sukumar 1994 Mad., it was held that willful

neglect of the husband constitutes desertion.

2. Cruelty: If husband through his actions creates sufficient apprehension in the mind of

the wife that living with the husband is injurious to her then that is cruelty. In the case

of Ram Devi vs Raja Ram 1963 Allahbad, if the husband treats the wife with

contempt, resents her presence and makes her feel unwanted, this is cruelty.

3. If the husband is suffering from a virulent form of leprosy.

4. If the husband has another wife living. In the case of Kalawati vs Ratan 1960

Allahbad, is has been held that it is not necessary that the second wife is living with

the husband but only that she is alive.

5. If the husband keeps a concubine or habitually resides with one. In the case of Rajathi

vs Ganesan 1999 SC, it was held that keeping or living with a concubine are extreme

forms of adultery.

6. If the husband has ceased to be a Hindu by converting to another religion.

7. For any other reasonable cause. In the case of Kesharbai vs Haribhan 1974 Mah, it

was held that any cause due to which husband's request of restitution of conjugal rights

can be denied could be a good cause for claiming a separate residence as well as

maintenance. In the case of Laxmi vs Maheshwar 1985 Orrisa, it was held that if the

husband fails to obey the order of restitution of conjugal rights, he is liable to pay

maintenance and separate residence

Section 18(3) says that a wife is not eligible for separate residence and maintenance if she is

unchaste or has ceased to be a Hindu.

In the case of Dattu vs Tarabai 1985 Bombay, it was held that mere cohabitation does not

by itself terminate the order of maintenance passed under 18(2). It depends on whether the

cause of such an order still exists.

Maintenance (Alimony) under Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

Various rights have been attributed to Hindu wife and husband on matrimonial issues under

the Hindu Marriage Act. Yet on few issues the rights of wife and husband are different from

each other but on many issues both the spouses stand on equal footing. Right of alimony is

also one of them.

Alimony means the allowances which husband or wife by court order pays to other spouse for

maintenance while they are separated or after they are divorced (permanent alimony) or

temporarily, pending a suit for divorce (pendente lite). The principle is that one who is unable

to maintain oneself, has a right to be maintained. The object is not to publish but to make

realize ones legal liability, to provide for those who are unable to support themselves, to

make the weaker section of the society to exist the live, to prevent destitution on public

grounds and on the basis of moral support as well, the subject is legally acknowledged.

Maintenance Pendente Lite:

The object of enacting the provision for maintenance and expenses during the pendency of

the proceeding in Section 24 is that a wife or husband, who has no independent income

sufficient for her or his support or enough to meet necessary expenses of the proceedings,

may not be handicapped. So the doctrine of pendente lite and permanent alimony is based on

economic tutelage of a spouse. It aims at administering justice and maintaining equilibrium

between the parties.

This section applies to both husband and wife equally. Law has placed both the spouses on

the same footing for this purpose.

The power of the court of ordering alimony pendente lite in a pending proceeding for

matrimonial relief has been provided by Sec. 24 of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. The liability is

on the person who initiates the proceedings to maintain the opposite party during the

pendency of the proceedings if the opposite party is unable to maintain herself and to meet

the expenses of the proceedings.

In order of alimony pendente lite should be supported by reasons and the applicant is to

establish that he or she has no independent income sufficient for his or her support and for

necessary expenses of the proceeding or if he or she has income the nature of quantum of it,

the income, of the respondent of the application for alimony and the quantum thereof, the

nature and extent of applicants needs both for maintenance and expenses of proceedings.

The discretion in the matter of granting maintenance pendente lite and cost of litigation is to

be exercised on sound legal principles. If the applicant has no independent means, he or she is

entitled to interim maintenance and expenses unless good cause is shown for depriving him or

her of it. The matters that may properly be considered in this connection are:

(i) whether applicant is being supported by an adulterer, and

(ii) whether the respondent has not sufficient means.

Thus, where the wife was prepared to go and live with the husband but the husband did not

wish to keep her with him on the ground of her inability of consummate the marriage the wife

is entitled to maintenance. The fact that the petitioning spouse is maintained by his or her

parents is no ground to deprive the petitioner of his or her maintenance and expenses of

litigation. For considering the application for grant of interim maintenance, only independent

income of the petitioning spouse or the conduct of her is material.

The expression sufficient in the collocation of the word sufficient means for his or her

support. Sufficient is not some. The word sufficient connotes that the income of the

applicant must be such which would be sufficient for a normal person for his or her

sustenance as well as to meet the necessary expenses of the proceeding. So the fact that the

wife sits in her fathers shop and earns a paltry sum by knitting and by tuition is not relevant

in deciding the question of alimony pendente lite, neither the fact that the father of the wife is

suporting her nor her refusal to live with the husband could be any ground for denial of

maintenance under Section 24. The question whether the wife is guilty of desertion cannot be

decided at the time of passing order of maintenance pendente lite.

It is noticeable that Section 24 only refers to income and not other property. So in case of

alimony pendente lite other property of the spouses should not enter judicial consideration.

Therefore immovable property yielding no income cannot be considered. Only the income

out of it received by the applicant can enter judicial consideration.

To have almony pendente lite it is not necessary that petitioners should have no income of her

or his own. If the income of the petitioners is found by court to be insufficient to support

her/him the court may order the other party to pay to the petitioner an allowance monthly and

litigation expenses. Even if the petitioner fails to aver that she has no source of income the

petition is not liable to be dismissed. The word sufficient is a relative term and has to be

considered on facts of each case.

The words wife having no independent income insufficient for her support suggests that

income of the wife must be independent and must be sufficient for her support. So, even if the

wifes parents are affluent, the wife has no independent income of her sufficient to support

her is entitled to maintenance pendente lite under Section 24 of the Act. The plea of having

no job when the husband is qualified and he refuses several offers of job on the pretext that it

would not suit him is not available as a defence against a petition for alimony pendente lite by

wife.

A husband who voluntarily incapacitates himself cannot be absolved of his liability to

maintain the wife. In Sousseau Mitra v. Chandana Mitra, the husband graduate in science

and a B.Ed. coming from respectable family and able bodied capable of earning, contended

that he was earlier working as a typist-cum-clerk but had resigned and so was out of

employment. The Court held that he couldnt avoid his liability to maintain his wife and child

by voluntarily incapacitate himself. The Court can legitimately take into consideration his

ability to earn a reasonable amount.

Alimony pendente lite and litigation expenses may be granted in any proceedings under the

Hindu Marriage Act provided other conditions for such grant are satisfied.

Section 24 does not bar proceedings under Section 125 of Cr.P.C., being separate and

independent remedies. Also by reason of Section 4(b) of Hindu Marriage Act it does not

prevail over the provisions under Cr.P.C. The amount of maintenance fixed under Section

125 of Cr.P.C. may be taken into account while awarding maintenance pendente lite.

Permanent Alimony: Section 25

Section 25 makes provisions for the grant of permanent alimony. The object of this section is

to treat both the husband and the wife on equal footing for the purpose of financial assistance

to be rendered permanently to the spouse who is poverty-stricken without having any

independent income of its own for maintenance and support. This grant of permanent alimony

and maintenance is circumscribed by two conditions. First, this grant will remain in force till

the applicant remains unmarried and pursues the chaste life. Secondly, this grant is the

personal right of the applicant and extinguishes with the death of the applicant.

This section differs from the provisions of similar legislations on this issue to the effect that

under analogous laws permanent alimony is granted only to the wife, but this section

recognizes this right for both the spouses alike following the legal principle of equality before

law. Though Section 25 does not use the expression permanent alimony in any part of the

enactment, the marginal note to the section clearly shows that the section is intended to deal

with permanent alimony.

The concept of permanent alimony is not an indigenous concept grown on the soil and there

was no law of divorce amongst Hindus in the country. The reason for awarding permanent

alimony to the wife seems to be that if the marriage bond which was at one time regarded as

indissoluble is to be allowed to be severed in larger interest of society, the same

considerations of public interest and social welfare also require that the wife should not be

thrown on the street but should be provided for in order that she may not be compelled to

adopt a disreputable way of life. The provision for permanent alimony is, therefore, really

incidental to the granting of a decree for judicial separation, divorce or annulment of marriage

and that also appears to be clearly the position if the language of Section 25 is looked at.

The right of permanent alimony is statutory right and as such it cannot be abridged or taken

away by any contract of the parties to that effect. Thus the husband cannot contract out nor is

the wife bound by any such contract.

It is significant to note that the relief of permanent alimony is a relief incidental to the

granting of the substantive relief by the Court in the main proceeding. It is an incidental relief

claimed in the main proceeding, though an application is necessary for claiming it. The

application is an application in the main proceeding for claiming an incidental relief

consequent upon the granting of the substantive relief by the Court.

Section 25 differs from Section 18 of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956.

Though this section confers power on the Court to order the permanent alimony and

maintenance but this power is discretionary and is exercised with reference to certain well

established principles. On the other hand, Section 18 of the H.A.M.A. does not provide any

such discretionary power and as such the Court is to pass order under this section on

determination of question of facts and questions of law. Thus, no question of judicial

discretion is involved in this matter. Further Section 4 of the HAMA, 1956 does not impliedly

repeal Section 25 of the Act. Under Section 18, husband is personally liable for his wifes

maintenance because such right is an incident of the status of matrimony. For such right valid

marriage is a pre-condition. This right of wife is a part of our ancient law but such right does

not accrue in case of void marriage. The right may be refused if decree on restitution of

conjugal right is operating against wife.

Section 25 does not deprive the wife of her right of maintenance even if the divorce is granted

on the ground of desertion on the part of the wife. The Court can in appropriate cases grant

relief of maintenance to women from the estate of her deceased husband even though it is

found by the Court that the marriage was void. It may be noted that in sub-section (1) of

Section 25, apart from various other matters to be taken into account, the Court is also to take

into account the conduct of the parties when a request is made for payment of alimony and

maintenance. Sub-section (2) provides for the Court varying, modifying or rescinding any

order already passed under sub-section (1) on being satisfied that there is a change in the

circumstances of either party at any time after the order was passed under sub-section (1). But

there is another special provision contained in sub-section (3) making it obligatory on the

Court to cancel an order passed under sub-section (1), under the circumstances mentioned in

that sub-section, the Court has to cancel an order passed under Section 25(1). These

circumstances are:

(i) The party in whose favour maintenance is awarded has remarried.

(ii) If that party is the wife, that she has not remained chaste, and

(iii) If such party is the husband, that he had sexual intercourse with any women outside

wedlock.

In the context of Section 25 the expression, any decrees means any of the decree referred to

in the earlier provision of the Act, i.e. nullity of marriage, or of divorce passed under Sections

9 to 13 of the Act. When the main petition is dismissed and no substantive relief is granted

under Sections 9 to 14, there is no passing of a decree as contemplated by Section 25 and the

jurisdiction to make an order for maintenance under the section does not arise. The term any

decree in the section, however, cannot be construed to include every decree. In Bhau

Saheb v. Leelabai the issue involved was whether an order dismissing a wifes petition

seeking declaration that marriage was valid can come under the term any decree. The Court

considered some hypothetical situation to indicate that the term any decree cannot be

expanded or stretched too liberally to include any Court order.

MAINTENANCE UNDER MUSLIM LAW

MAINTENANCE

Maintenance is a right to get necessities which are reasonable from another. It has been held

in various cases that maintenance includes not only food, clothes and residence, but also the

things necessary for the comfort and status in which the person entitled is reasonably

expected to live. The term maintenance means proper maintenance and it should not be

narrowly interpreted.

WIFES RIGHT TO MAINTENANCE UNDER MUSLIM LAW:

A Muslim husband is bound to maintain his wife of a valid marriage even if she is rich, and

not withstanding that the husband is without any means. He is also bound to maintain his wife

in a particular instance of an irregular marriage viz. when the marriage is irregular for want of

witnesses. The wifes right of maintenance is a debt against the husband and has priority over

the rights of all other persons to receive maintenance. The wife, however, has no right to

pledge the credit of her husband for providing herself with maintenance.

In Muslim law, the obligation to maintain wife does not commence on marriage and it exists

only so long as the wife remains faithful to him and obeys all his reasonable orders. But the

wife does not lose her right to maintenance if:

(a) she refuses access to her husband on some lawful grounds, such as when the husband

keeps a concubine, or is guilty of cruelty towards her (wife), or

(b) marriage cannot be consummated owing to:

(i) husband having not attained puberty,

(ii) his absence without her prior permission, or

(iii) his illness, or

(iv) malformation

It is pertinent to mention here that the wife cannot exercise her right of maintenance except

after it has become due.

So far as the quantum of maintenance is concerned, there is a difference of opinion among the

Muslim authorities as to the amount of maintenance a wife is entitled to receive from her

husband. It seems that under Hanafi law, the rank and the financial position of both the

parties are to be considered, while under the Shafii law, only that of the wife, and the amount

of maintenance is to be determined on the basis of wifes requirements of condiments, food,

clothing, residence, service and implements of anointing, due regard being also had to the

custom of her equals among her own people in the same city. It further appears that that the

wife (and where there are more than one wives, each wife) is also entitled to a separate

apartment for herself, free from the intrusion of any person other than her husband.

DIVORCED WIFES RIGHT TO MAINTENANCE

Holy Quran imposed an obligation on the Muslim husband to make provision for or to

provide maintenance to the divorced wife but prior to the decision of the Supreme Court in

Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum, a divorced Muslim wife was not entitled to any

maintenance from her husband after the expiry of the period of iddat.

In the Shah Bano case the Supreme Court held that:

Under section 125(1)(a) of the Code of Criminal Procedure,1973, a person who, having

sufficient means, neglects or refuses to maintain his wife who is unable to maintain herself,

can be asked by the court to pay a monthly maintenance to her at a rate not exceeding Five

Hundred Rupees. By clause (b) of the Explanation to section 125(1), wife includes a

divorced woman who has not remarried. These provisions are too clear and precise to admit

of any doubt or refinement. The religion professed by a spouse or by the spouses has no place

in the scheme of these provisions. Since the Muslim Personal Law, which limits the

husbands liability to provide for the maintenance of the divorced wife to the period of iddat,

does not contemplate or countenance the situation envisaged by section 125, it would be

wrong to hold that the Muslim husband, according to his personal law, is not under all

obligation to provide maintenance, beyond the period of iddat, to his divorced wife who is

unable to maintain herself. The true position is that, if the divorced wife is able to maintain

herself, the husbands liability to provide maintenance for her ceases with the expiration of

the period of iddat. If she is unable to maintain herself, she is entitled to take recourse to

section 125 of the Code.

Considering the controversy and outrage following the Shah Bano ruling, the Indian

Parliament passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act in 1986. This

Act makes provisions for the protection of the rights of Muslim women who have been

divorced by, or have obtained divorce from, their husbands, which includes right of

maintenance as well.

It is interesting that the Supreme Court has again extended this protection to the divorced

Muslim women by ruling that provision including maintenance extending beyond the iddat

period must be made by the husband within the iddat period by terms of S. 3(1)(a) of the Act

of 1986. It has been held that a Muslim wife is entitled to Maintenance under Section 125 till

divorce by her husband is communicated to her.

The constitutional validity of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act,

1986, was challenged in the case of Danial Latifi v. Union of India and while upholding the

validity of the Act, the Apex Court summed up its conclusions as follows:

1) Muslim husband is liable to make reasonable and fair provision for the future of the

divorced wife which obviously includes her maintenance as well. Such a reasonable

and fair provision extending beyond the iddat period must be made by the husband

within the iddat period in terms of Section 3(1)(a) of the Act.

2) Liability of Muslim husband to his divorced wife arising under Section 3(1)(a) of the

Act to pay maintenance is not confined to iddat period.

3) A divorced Muslim woman who has not remarried and who is not able to maintain

herself after iddat period can proceed as provided under Section 4 of the Act against

her relatives who are liable to maintain her in proportion to the properties which they

inherit on her death according to Muslim law from such divorced woman including her

children and parents. If any of the relatives being unable to pay maintenance, the

Magistrate may direct the State Wakf Board established under the Act to pay such

maintenance.

4) The provisions of the Act do not offend Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution of

India.

Section 5 of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 also says that

If, on the date of the first hearing of the application under sub-section (2) of Section 3, a

divorced woman and her former husband declare, by affidavit or any other declaration in

writing in such form as may be prescribed, either jointly or separately, that they would prefer

to be governed by the provisions of Section 125 to 128 of the Code of Criminal Procedure,

1973, and file such affidavit or declaration in the Court hearing the application, the

Magistrate shall dispose of such application accordingly and as per explanation of Section 5,

for the purposes of this section, date of the first hearing of the application means the date

fixed in the summons for the attendance of the respondent to the application.

Latest Case on this issue

Shabana Bano Vs Imran Khan 2010 (1) CTC 121

Muslim Women (protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 (25 of 1986), Section 4 Claim

of maintenance by divorced Muslim woman Whether restricted for iddat period only

Whether Petition under Section 125 of Cr.P.C. maintainable before Family Court Held:

Maintenance to be awarded under Section 125 of Cr.P.C. cannot be restricted for iddat period

only Divorced Muslim woman entitled to claim maintenance from her divorced husband as

long as she does not remarry Divorced Muslim women will be entitled to claim

maintenance from her husband under Section 125 of Cr.P.C. after expiry of period of iddat as

well.

Facts: The basic and foremost question that arises for consideration is whether a Muslim

divorced wife would be entitled to receive the amount of maintenance from her divorced

husband under Section 125 of Cr.P.C. and if yes, then through which forum. The Appellants

petition under section 125 of the Cr.P.C., would be maintainable before the Family Court as

long as appellant does not remarry. The amount of maintenance to be awarded under Section

125 of the Cr.P.C., cannot be restricted for the iddat period only. Cumulative reading of the

relevant portions of judgment of this Court in Danial Latifi would make it crystal clear that

even a divorced Muslim woman would be entitled to claim maintenance from her divorced

husband, as long as she does not remarry. This being a beneficial piece of legislation, the

benefit thereof must accrue to the divorced Muslim women.

In the light of the aforesaid discussion, the impugned orders are hereby set aside and quashed.

It is held that even if a Muslim woman has been divorced, she would be entitled to claim

maintenance from her husband under Section 125 of the Cr.P.C., after the expiry of period of

iddat also, as long as she does not remarry.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Final Draft of CRPCDocument16 paginiFinal Draft of CRPCKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transfer for unborn under Section 13Document20 paginiTransfer for unborn under Section 13Umakanta ballÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maintenance Under Hindu LawDocument14 paginiMaintenance Under Hindu LawunnatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sources of Muslim LawDocument5 paginiSources of Muslim Lawparijat_96427211100% (1)

- Hindu Succession Act 1956Document47 paginiHindu Succession Act 1956Danika JoplinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short Notes On Hindu Joint Family. Mitakshara and DayabhagaDocument8 paginiShort Notes On Hindu Joint Family. Mitakshara and DayabhagaS P BarbozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hindu Succession-Male & FemaleDocument14 paginiHindu Succession-Male & FemaleKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Female Hindu Intestate SuccessionDocument9 paginiFemale Hindu Intestate Successionm sÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1111 Difference Between Joint Hindu Family and CoparcenaryDocument12 pagini1111 Difference Between Joint Hindu Family and CoparcenaryAmitDwivedi100% (2)

- Env Law SyllabusDocument3 paginiEnv Law SyllabusKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical analysis of Alimony and maintenance as an independent remedyDocument6 paginiCritical analysis of Alimony and maintenance as an independent remedyheer10298_734179785Încă nu există evaluări

- Right To Maintenance of Hindu Women Under Hindu Adoption and Maintenance ActDocument6 paginiRight To Maintenance of Hindu Women Under Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Actaryan jainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Law II Modules on Hindu and Muslim Adoption, Maintenance, Joint Family, Coparcenary, Partition, Succession and InheritanceDocument4 paginiFamily Law II Modules on Hindu and Muslim Adoption, Maintenance, Joint Family, Coparcenary, Partition, Succession and InheritanceMuskan KhatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Section 84 IpcDocument11 paginiSection 84 IpcGauri ChuttaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Hinu Law Project On AdoptionDocument10 paginiFinal Hinu Law Project On AdoptionShubhamPatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analytical Study of Rights, Duties and Liabilities of MembersDocument8 paginiAnalytical Study of Rights, Duties and Liabilities of MembersKHUSHI KATREÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Law - IiDocument30 paginiFamily Law - IiZeel kachhiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guardianship Under Hindu Law-2Document6 paginiGuardianship Under Hindu Law-2Kumari RimjhimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transfer for benefit of unborn: Key aspects of Section 13Document44 paginiTransfer for benefit of unborn: Key aspects of Section 13Manav BhagatÎncă nu există evaluări

- RatificationDocument13 paginiRatificationDishant MittalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Categorisation of Hindu PropertyDocument17 paginiCategorisation of Hindu PropertyKarman AulakhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meaning of A Director: " Any Person Occupying The Position of Director, by Whatever Name Called" - Sec. 2Document21 paginiMeaning of A Director: " Any Person Occupying The Position of Director, by Whatever Name Called" - Sec. 2smsmbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Law - I, Abhishek SinghDocument28 paginiFamily Law - I, Abhishek SinghSinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trespass to Land and Related TopicsDocument21 paginiTrespass to Land and Related Topicsvrinda sarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hurt and Grievous HurtDocument9 paginiHurt and Grievous HurtAshish SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule of Feeding The Grant by Estoppels (Section 43)Document11 paginiRule of Feeding The Grant by Estoppels (Section 43)AN HadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hindu Law Key ConceptsDocument6 paginiHindu Law Key ConceptsNisha NishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who Is The Ostensible OwnerDocument10 paginiWho Is The Ostensible OwnerdeepakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept of Gift and Wasiyat under Muslim Personal LawDocument11 paginiConcept of Gift and Wasiyat under Muslim Personal LawRadhikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Property Law Project Transfer of Property by Ostensible OwnerDocument6 paginiProperty Law Project Transfer of Property by Ostensible OwnerShaji SebastianÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASSIGNMENT ON Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956Document17 paginiASSIGNMENT ON Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956Abdul MannanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syed Mohammad Raza Vs Abbas Bandi Bibi On 12 April, 1932Document5 paginiSyed Mohammad Raza Vs Abbas Bandi Bibi On 12 April, 1932samiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Changes by Hindu Succession ActDocument6 paginiChanges by Hindu Succession ActvaibhavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Testamentary Guardianship by Ishu SainiDocument6 paginiTestamentary Guardianship by Ishu SainiIshu SainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Position of DirectorsDocument3 paginiLegal Position of DirectorsHeta_Chauhan_36620% (1)

- H.P National Law University, Shimla: Family Law-Ii Assignment Submitted ToDocument7 paginiH.P National Law University, Shimla: Family Law-Ii Assignment Submitted Tokunal mehtoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karta's Power of AlienationDocument10 paginiKarta's Power of Alienationkriti mishra0% (1)

- EPF & Miscellaneous Provisions Act 1952 SummaryDocument7 paginiEPF & Miscellaneous Provisions Act 1952 SummaryMehak KaushikkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nullity of MarriageDocument7 paginiNullity of Marriagemihir khannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LAW Partnership Act 1932Document10 paginiLAW Partnership Act 1932ritesh2030Încă nu există evaluări

- Muslim FL Case LawsDocument4 paginiMuslim FL Case Lawsmanya jayasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health Act 1987Document7 paginiMental Health Act 1987Arundhati BhatiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hindu Marriage Act 1955 and Special Marriage Act 1954 Grounds for DivorceDocument2 paginiHindu Marriage Act 1955 and Special Marriage Act 1954 Grounds for DivorceMAYANK GUPTAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relations of Partners Inter SeDocument8 paginiRelations of Partners Inter SeRahul kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alteration of MemorandumDocument10 paginiAlteration of Memorandumjain7738Încă nu există evaluări

- Sunni Law of Inheritance: An IntroductionDocument19 paginiSunni Law of Inheritance: An IntroductionZeesahnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benefits of Unborn ChildDocument3 paginiBenefits of Unborn ChildAdan HoodaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hindu Joint FamilyDocument17 paginiHindu Joint Familyrajesh_k69_778949788Încă nu există evaluări

- Danial Latifi Vs Union of IndiaDocument6 paginiDanial Latifi Vs Union of IndiaArjun PaigwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Void Bequests & Void Wills - Family LawDocument27 paginiVoid Bequests & Void Wills - Family Lawjavvad shaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- White CollarDocument46 paginiWhite CollarRakesh BÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contractual Liability of The State in IndiaDocument10 paginiContractual Liability of The State in IndiaSatyam KhandelwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guardianship under Muslim Law ExplainedDocument8 paginiGuardianship under Muslim Law ExplainedSammy JacksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Hindu Joint Family or Hindu Undivided FamilyDocument5 paginiA Hindu Joint Family or Hindu Undivided Familyurs3012Încă nu există evaluări

- Adoption & Maintenance (Family Law)Document17 paginiAdoption & Maintenance (Family Law)Karthik100% (1)

- GUARDIANSHIP UNDER MUSLIM LAWDocument4 paginiGUARDIANSHIP UNDER MUSLIM LAWAbhijeet kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Onerous Gifts Legal Trends IndiaDocument7 paginiOnerous Gifts Legal Trends IndiaGunjeetÎncă nu există evaluări

- UNIT 1 All TopicsDocument70 paginiUNIT 1 All TopicsAnish KartikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joseph Vellikunnel v. RBIDocument5 paginiJoseph Vellikunnel v. RBIJINTA JAIMON 19213015Încă nu există evaluări

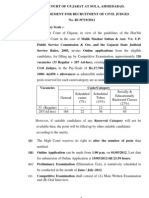

- Civil Judge Recruitment 2012 ComDocument15 paginiCivil Judge Recruitment 2012 ComDeweducationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improvements under defective titlesDocument5 paginiImprovements under defective titlesBharath YJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intellectual Property: The Lifeblood of Your CompanyDe la EverandIntellectual Property: The Lifeblood of Your CompanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Law-Ii Project On Maintenance Under Hndu Law SUBMITTED TO: Professor Kahkashan Y. DanyalDocument10 paginiFamily Law-Ii Project On Maintenance Under Hndu Law SUBMITTED TO: Professor Kahkashan Y. DanyalRoopali GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Law-Ii Project On Maintenance Under Hndu Law SUBMITTED TO: Professor Kahkashan Y. DanyalDocument10 paginiFamily Law-Ii Project On Maintenance Under Hndu Law SUBMITTED TO: Professor Kahkashan Y. DanyalRoopali Gupta100% (1)

- BCI Verification Rules 1 3Document25 paginiBCI Verification Rules 1 3Kumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter-Iii Evolution of Drug Abuse Control Law in India: 1 v. (1969) 24L Ed. (2d) 610Document36 paginiChapter-Iii Evolution of Drug Abuse Control Law in India: 1 v. (1969) 24L Ed. (2d) 610Kumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beneficent Construction RuleDocument8 paginiBeneficent Construction RuleKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 - 3 - Flavia Agnes - Triple TalaqDocument19 pagini10 - 3 - Flavia Agnes - Triple TalaqKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statutory Interpretation ToolsDocument8 paginiStatutory Interpretation ToolsKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- CivilProcedureRulesPart07 PDFDocument16 paginiCivilProcedureRulesPart07 PDFKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noise Pollution Rules GuideDocument7 paginiNoise Pollution Rules GuideSaravanan ElumalaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Are Five Principle Theories of Corp PersonalityDocument2 paginiThere Are Five Principle Theories of Corp PersonalityKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bonus SharesDocument3 paginiBonus SharesKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamental Principles of Env LawDocument22 paginiFundamental Principles of Env LawKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1Document12 paginiChapter 1Kumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Register Rules for CompaniesDocument5 paginiRegister Rules for CompaniesKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labour Law 2 Final ProjectDocument19 paginiLabour Law 2 Final ProjectKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dilution ArticleDocument4 paginiDilution ArticleKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Myth and Reality of Dilution PDFDocument101 paginiThe Myth and Reality of Dilution PDFKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law of MaintenanceDocument11 paginiLaw of MaintenanceKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legislative Intent and Statutory Interpretation in England and THDocument25 paginiLegislative Intent and Statutory Interpretation in England and THKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collective Bargaining Guide WebDocument24 paginiCollective Bargaining Guide WebKumar Mangalam100% (1)

- Final Research Project of Family Law - 2Document13 paginiFinal Research Project of Family Law - 2Kumar Mangalam100% (2)

- The Harrowing ExecutionDocument5 paginiThe Harrowing ExecutionKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- YagnaPurusdasji V Muldas - 1 PDFDocument15 paginiYagnaPurusdasji V Muldas - 1 PDFKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Economic GrowthDocument14 paginiIndian Economic GrowthKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- T.P.A. Bare ActDocument108 paginiT.P.A. Bare ActKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project of ContractDocument16 paginiProject of ContractKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uniform Civil CodeDocument5 paginiUniform Civil CodeKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sources of Hindu LawDocument6 paginiSources of Hindu LawKumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări