Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Evans - The Root Locus Paper

Încărcat de

pss1962030 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

225 vizualizări7 pagini1) Walter Evans was frustrated by the slow review process of his "root locus" paper by the American Institute of Electrical Engineering (AIEE). He vented his frustration in a letter to Professor Gordon Brown, who was overseeing the review.

2) Evans worked as an engineer at North American Aviation, developing flight control systems for rockets and missiles to compete with the Soviet space program during the Cold War.

3) Evans' "root locus" method provided a new way to design stable feedback control systems, which was important for inertial guidance systems needed for missile development.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest document1) Walter Evans was frustrated by the slow review process of his "root locus" paper by the American Institute of Electrical Engineering (AIEE). He vented his frustration in a letter to Professor Gordon Brown, who was overseeing the review.

2) Evans worked as an engineer at North American Aviation, developing flight control systems for rockets and missiles to compete with the Soviet space program during the Cold War.

3) Evans' "root locus" method provided a new way to design stable feedback control systems, which was important for inertial guidance systems needed for missile development.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

225 vizualizări7 paginiEvans - The Root Locus Paper

Încărcat de

pss1962031) Walter Evans was frustrated by the slow review process of his "root locus" paper by the American Institute of Electrical Engineering (AIEE). He vented his frustration in a letter to Professor Gordon Brown, who was overseeing the review.

2) Evans worked as an engineer at North American Aviation, developing flight control systems for rockets and missiles to compete with the Soviet space program during the Cold War.

3) Evans' "root locus" method provided a new way to design stable feedback control systems, which was important for inertial guidance systems needed for missile development.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 7

The Root Locus Paper

Walter R. Evans and the Story of Root Locus

On Saturday, May 7, 1949, at the Polo Grounds, the New York Giants delivered a 9-1 drubbing

to the St. Louis Cardinals, hometown team of a twenty-nine year old electrical engineer and

baseball fan, Walter R. Evans. A third generation St. Louisan, Evans now lived with his wife

Arline (also third generation St.Louisan) and two young sons, Randy (age 4) and Gregory (age 1)

in Whittier, California, about 15 miles east of Los Angeles.

Despite Saturday being a day off, the impatient Evans was mad. His anger had nothing to do

with the 9-1 drubbing and everything to do with a frustration born of six months of waiting. In

December 1948 he had submitted his second servomechanisms

1

paper to the American Institute

of Electrical Engineering (A.I.E.E.). Just as had occurred in 1947, he had become frustrated by

the agonizingly slow review process. He had already missed out on the 1949 winter general

meeting because one critic complained about the papers length. Now, two months since he

resubmitted a shorter version, he remained in the dark about its acceptability. Would it require a

year, as it had with his 1947 graphical analysis paper, before his new root locus idea would

receive a hearing at a general meeting? Were open-minded reviewers assigned his papers, or, as

he feared, were close-minded ones critiquing it? At work, open-minded engineers gravitated to

his new idea; some senior ones seemed annoyed at being asked to think differently.

He sat down and vented his anger toward the one person in whose hands he believed the fate of

his paper sat, Professor Gordon S. Brown, founder and director of MITs Servomechanism

Laboratory and chairman of the Technical Program Committees servomechanism

subcommittee.

The A.I.E.E. has now had the Root Locus paper for nearly six months. In my humble

opinion this pathetic record for an Institute which is alleged to have dissemination of new

theories .. as one of its fundamental aims. This is a subject on which I might write in

undeniably clear language if there were reason to believe it might do some good.

He finished the draft of the letter and set it aside for the time being.

1

Servo in servomechanism means slave in Latin. One example of a servomechanism is the

complex machinery that causes the Hubble Telescope to point exactly at a particular galaxy when an

astronomer enters the galaxys coordinates. The servomechanism tries to reduce to zero the difference

between the direction the astronomer has told the telescope to point and the direction its sensors tell it is

pointed. Machines take time to respond to commands, however, and these delays induce an oscillatory

behavior. Servomechanism designers want to the amplitude of these oscillations to always decrease

over time. This behavior is stable. Oscillations that grow over time are unstable. Evans root locus

method provided a new way for engineers to be confident their designs moved into stability.

2

That same Saturday, about ten thousand miles away at the Kapustin Yar launch site, Soviet

scientists celebrated the first successful launch of their R1-A Scunner rocket, a version of the

German V-2 rocket that had been used with devastating effect in the war. They had overcome

their most vexing problem -- flight control -- to achieve a successful 270 km flight. Five more

successes would follow in the month of May.

Although this Soviet success was, of course, unknown to Evans, he was well aware of Americas

competition with the Soviet Union. Three years had passed since Winston Churchill had

famously declared in Fulton, Missouri, From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an

iron curtain has descended in the continent. In May 1949, memories of the US-Soviet alliance

that had brought victory over the axis powers were fresh, but relations between the former allies

had grown tense. Less than a year before, the Soviets tried to block western access to Berlin.

Unlike the world war recently ended, this new cold war would not be led by generals nor

fought by soldiers on battlefields. Rather, it would be led by scientists and waged by engineers

in their respective laboratories and rocket test ranges. Evans was a new recruit on the front line

of this war, having emigrated nine months previously from St. Louis to join North American

Aviations Aerophysics Laboratory in Downey, California.

Four years before, as the war was coming to an end, North Americans president James Howard

Dutch Kindelberger had formed a small, secret Technical Research Laboratory in Inglewood

for several staff to study rocketry. Once the war ended, the militarys needs shifted immediately

from high volume aircraft manufacturing to long-range ballistic missiles. By 1949, their

requirements for range had increased to 1000 nm on their way to 5500 nm and the requirements

for accuracy had become a very significant challenge. New technology was needed across a

wide range of engineering discipline, but none was more important than design of the internal

compasses that put the guided in guided missiles their inertial references and associated

flight control systems. Kindelberger and his successor as NAA president, J. Lee Atwood,

created a new larger organization called the Aerophysics Laboratory and challenged it to become

the best in every technology associated with ballistic missiles.

To lead this new organization they needed someone with proven leadership, managerial, and

technical ability. Atwood chose William C (Bill) Bollay, a former Ph.D. aeronautics student of

Caltechs Theodore von Karmen. John Moore, an associate professor of mechanics at

Washington University, joined the laboratory to form the engineering team to build small,

accurate, inertial guidance systems. Among the first people he sought out was a twenty-eight

year old engineer he had helped become an instructor at Washington University --Walter Evans.

In June 1948 Evans joined NAA for summer employment between academic years. He found

himself intellectually challenged and, given his growing family, attracted by the pay differential.

He returned to St. Louis and drove his family west, where they would settle in Whittier.

Evans found himself among an elite team of engineers working for John Moores organization.

North American Aviation (NAA) has a contract with the Army Air Corps to develop an

American version of the German V-2 rocket to become known as the NAVAHO. (North

American liked to see their products begin with the letters NA) Evans area of expertise

feedback control systems used by servomechanisms was key to solving the technical problems

3

that his Soviet counterparts had struggled to overcome automatic flight control of a ballistic

missile using an inertial reference system.

In early 1940s Evans and Moore had studied together while at the General Electric Companys

Advanced Course in Schenectady, NY. Through GEs technical library they followed advances

in principles of servomechanism design, including MITs latest prepublication papers distributed

in advance of A.I.E.E.s quarterly meetings. In professors Charles Stark Draper and Gordon S.

Brown, MIT had unchallenged leadership in the fields of servomechanisms and inertial guidance

systems. The American military had invested heavily at MIT during the war to develop the first

radar, and later in the antiaircraft fire control systems that used radars as sensors --military

examples of servomechanisms. Many years later, Evans kept a prepublication copy of a 1945

paper -- No 45-A-20 Dynamic Behavior and Servomechanism Design in his files. Its authors

were Gordon Brown and his associate, Albert C. Hall. In fact, Evans first reference in his root

locus paper was to Gordon S. Browns 1948 book on servomechanisms.

Later that same Saturday, May 7, Evans returned to the draft of his letter to Gordon Brown.

Should he send it? What good would it do? Evans mind churned. Creative but impatient by

nature, his thinking process seldom stuck on the first solution that came to his mind. Rather he

would continue to seek out an alternate perspective that might expose a better solution to a

problem. He knew that John Moore and Gordon Brown had met within the last few days.

Among the topics he knew they would have discussed was his root locus paper. He knew he

could count on getting a report from Moore soon.

We cannot know what was in his mind. What we do know is he decided to rewrite the letter with

a strained attempt at humor and a suggestion that amounted to a threat. Dr. Professor Brown,

he wrote again. Trying a dozen plays on words, he wrote, in part:

The root locus idea has been chasing around for six months in some multiple loop with no

visible output. The only feedback has been rejection and your recent letters. There must

be something nonlinear in the system. The obvious alternative is to submit the paper to a

different organization.

He sent this second letter airmail to Brown and scrawled, NOT SENT on his first draft.

Sunday May 8, would be a better day, at least for St. Louis. The Cardinals trounced their rivals

the Dodgers 14-5 at Ebbett's Field. The 1949 baseball season was still in its early stages. And

so, it would develop, was the review of Evans paper. The Cardinals, recent (1946) world

champions, led by 1948 batting champion Stan Musial, were hoping to at least win the pennant.

To do so, they would have to subdue the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Monday Morning, May 9, Evans drove down Imperial Blvd. from his modest Whittier home to

the Aerophysics facility in Downey. There he learned from Moore that the March 28 version of

the paper was still unacceptable to Brown. Moreover, Evans got the impression from Moores

comments that Brown did not yet see the value of his root locus method. Anxious to understand

what specifically Brown did not grasp; Evans wrote another letter to Brown before Brown would

have received his May 7 letter. Dear Prof. Brown, he wrote for the third time in as many days,

4

John Moore returned with the news that the Root Locus paper is still unacceptable to you.

Therefore I would appreciate a copy of the paper marked with your questions. He

finished the letter as he had the last one with I see no alternative to starting some action in

parallel with your committee.

At home that evening, he decided to take a more proactive approach by at taking his manual

typewriter and banging out four letters in one evening, all to former colleagues at GE and Wash

U Gordon Walter, Phil Michel, Louis (Doc) Radar, and Orrin Livingston. He could express

more freely to them what was really bugging him. Evans also realized he could use his friends as

conduits to get his idea into the institutions he had recently left by including a copy of his paper

with each letter sent. To Doc Radar he wrote,

Remember the low opinion that I had of the A.I.E.E. technical paper system in Pittsburgh?

Well, it has now sunk even lower. The enclosed paper was first submitted to the winter

meeting. Every bit of information I have received has been the result of needling them.

The fellows out here at the Aerophysics Lab at North American have adopted it in preference

to any of the standard methods. If you or any of the boys have any questions about the

method, I would be glad to answer them.

Tuesday, May 10, Gordon Brown received Evans letter of May 7. He responded with a carefully

worded letter that was both professionally polite and at the same time a stinging rebuke. He took

the unusual measure of asking his secretary to send the letter airmail.

Thursday evening May 12, Evans opened it Brown had enumerated his remarks from one to six,

starting five of the six with the word please. That he took offense at Evans comments is

apparent in item number four:

4. Please remember that if anyone seriously takes the job of reviewing manuscripts, they

spend a great deal of time in the interests of the authors professional reputation that is

purely voluntary and part of the code of professional ethics.

The sixth comment advised Evans Please talk to Mr. Moore upon his return to California and

get his advice before you let this matter go to far. Below the closing salutation, Evans saw that

he was not the only one to receive the feedback. Brown had sent both letters to three members of

A.I.E.Es Technical Committee and John Moore.

Browns structured rebuke left Evans was both contrite and angry. Immediately, he drafted a

point-by-point, typewritten draft response. To Browns fourth comment (quoted above) Evans

wrote,

You will perhaps excuse my overlooking the time volunteered by reviewers when you realize

the too long and show contribution to synthesis was essentially all I learned from the

initial rejection. The several hundred hours which I spend (sic) developing the method was

fun, but has been matched by now with write-ups and revisions. But most important, think of

5

the thousands of man-hours wasted by A.I.E.E. members on inefficient methods during a

publication delay like this.

By the time he finished the evening was late. He set the letter aside to sleep on it.

Friday, May 13: Evans followed Gordon Browns suggestion and went to John Moore to get his

guidance. This time Evans learned that Brown had told Moore that he himself had devoted hours

of his own time with root locus paper and had even considered rewriting it himself. From

colleagues he learned that they had complemented him on the paper in part because of their

knowledge of the hours Evans had put into writing it. Evans anger dissolved into a mixture of

contrition and personal embarrassment. He filed away yesterday evenings defiant draft and

composed a short letter of apology for his secretary to type and send to Brown. Dear Professor

Brown, he wrote for the fifth time in six days,

Nothing seems less funny than an attempt at humor which is out of place. I wish to apologize

for my letter of May 7, it was an ill-considered outburst releasing long accumulated

frustration. Any effort which you can make to ignore the recent letters would be

appreciated. I have been completely deflated. The only thing Im sure of at this time is the

sense of duty to revise the paper until acceptable.

Over the next two weeks, Evans did just that, and on May 29 sent the A.I.E.E. in New York his

rewritten paper. He dropped servomechanism, and chose the title Control System Synthesis

by Root Locus Method. He sent a copy to Gordon Brown at MIT.

The next letter he received came neither from the A.I.E.E. or Gordon Brown. Rather, it was

from GEs Orrin Livingston, who was responding to one of the four letters Evans had banged out

on May 9. Livingston confessed his bewilderment with the paper.

I struggled through a few pages am now referring it to some of the other boys in the hopes

they can explain it to me in words of one syllable. Incidentally, if you have anything of a

more elementary nature, we would like to receive a copy

By this time, of course, Evans had already made another pass at explaining root locus.

Although it was Brown, not Livingston, who controlled the fate of his paper, Livingstons

bewilderment bothered Evans; another idea began to percolate in his mind.

A week later, the letter carrying an MIT return address arrived. This time Browns comments

were considerably more favorable. Both Evans letter of apology and his rewritten paper had

had their hoped for affect on Brown, who wrote:

I am pleased to acknowledge receipt of the carbon copy of the final (italics added)

manuscript of your paper. I believe you have done an excellent job at working out the

suggestions made by the reviewers. I assume you sent. the necessary extra copies for

review.

Evans, of course, if he knew anything, knew to expect more review; he had sent copies.

6

Meanwhile, Evans worked up a response to Livingstons request for something of a more

elementary nature. The formal style expected of the A.I.E.E. papers had been a strain for Evans

to compose. His wife, John Moore, and other colleagues were drawn to him in part out of

respect for his intellect, but mostly for his sense of humor and naturally informal style. (Years

later, for example, he informed an applicant he was hired while playing touch football with him.)

Now, realizing he had never described root locus in a more informal way, he used Livingstons

letter as an opportunity to do so. By June 13 he had completed four handwritten pages he entitled

The Root Locus Idea, divided into paragraphs on Problem, The Classical Approach, The

Frequency Response Technique, Roots Their Lives and Habitats, and The Root Locus Plot.

The only extant copy is one Evans kept in his files; he never had it typed or published. In his

cover letter he included to Livingston, Evans wrote,

Ive long thought is would be a sporting idea to write up the root locus idea the way I

came to understand it free from approved terminology. Forget the synopsis and

introduction. Lets concentrate on the simple cubic system. Thats just tough enough to

illustrate the idea and no more. Incidentally, it took from 1946 to 1949 to hit upon the idea

and all the rest was worked up in 3 weeks so Im sure you can work out all the rest anyway.

Good luck with the enclosed write up.

That summer Evans put aside any further formal work on his paper and turned his attention to

developing a book about root locus. In a letter to John Wight, Editor of Engineering Books at

McGraw Hill in New York, Evans explained that the main purpose of the book is to

demonstrate the root locus method. The importance of his work at Aerophysics Laboratory was

surely brought home to him and all of Bollays NAVAHO missile team when word came that the

Soviet Union had exploded their first atomic bomb Joe 1 on August 29

th

on the steppes of

Kazakhstan in Central Asia. It was a virtual carbon copy of the American weapon. The Soviet

scientists had received Americas recipe from sympathizers and spies. Three days after the

Soviet atomic test, Evans signed a memorandum of agreement to prepare and supply to the

McGraw Hill Company a work entitled Control System Synthesis.

With regards to his root locus paper, still in the A.I.E.E. review process, Evans received some

help in August from Caltechs G.D. McCann, who wrote to reviewer Sy Herwald:

I believe this is a such an important contribution to the art of steady state analysis of linear

systems that every effort should be made to have it accepted by the A.I.E.E. as soon as

possible.

In September, the baseball season ended. Although it went down to the wire, the Dodgers edged

out the Cardinals for the National League championship by a single game. Stan Musials 0.338

batting average fell a few points short of the 0.342 posted by the Dodgers new leader, Jackie

Robinson, who won the batting championship. Just as it had with his 1948 Graphical Analysis

paper, an entire baseball season had come and gone while he had seemingly had struck out with

the A.I.E.E. review committees.

7

Finally, in mid-October, Evans learned that the A.I.E.E. would recommend the root locus paper

publication, but, as the fall meeting schedule was too full, it would probably (italics added) be

the 1950 winter general meeting before it would be presented putting its publication in

Transactions into 1950s baseball spring training season.

Much remains to be told of the root locus story. Yet to be written is the story of how Evans

came to write his book, of the 100,000 Spirules sent to 65 countries and of decades of

applications of the root locus method, including North Americans inertial guidance systems for

the NAVAHO missile and the Nautiluss voyage to the north pole.

Fifty years later, as dawn breaks on the twenty-first century, root locus continues to be part of the

standard curriculum of every introductory graduate course in control theory. In 1994, George

Thaler, Professor of Engineering at the Naval postgraduate School in Monterey, California,

complied a book of classic 21 classic papers on Automatic Control: Classical Linear Theory.

The last papers he chose to include were those Evans had persisted through three years of

waiting, wrangling, and rewriting to have published in the A.I.E.E. Transactions. In his

introduction of these two papers, Thaler wrote:

This group of two papers comprises the only post-World War II contributions in this volume.

In these papers Evans introduced the now-famous root-locus method. The first of these

papers is essentially background, in the sense that it shows the kind of thinking that later led

Evans to the root-locus method, and it also shows the elementary form of protractor which

later became the Spirule. Some of the conformal mapping ideas are useful and informative.

Our last paper is, of course, an exposition of the root-locus method itself. Little need be said

here, except to point out that the paper is very concise, yet contains a wealth of ideas. On

careful reading one realizes that, at the time of publication, Evans understanding of his

method and his ability to use it was at a level that most of use did not reach for another

fifteen years.

We have terminated this volume with the classic papers by Evans primarily because they

mark the last of the major, fundamental contributions to that is commonly known as the

classical theory of linear, continuous feedback control systems. There have been many

contributions to classical theory since 1950, but such contributions have largely been

expansions, clarifications, and applications of the fundamental ideas. Shortly after 1950 the

explosion in technical publications began, and in the field of automatic control, countless

papers have been published that deal with linear, non-linear, sampled data, adaptive, and

other types of systems. Many of these papers are indeed of major importance, and perhaps

collections of such papers may be of value, but none seems to be classic in the same sense as

the ones presented here.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Electric Spring For Voltage Stability and Power Factor CorrectionDocument3 paginiElectric Spring For Voltage Stability and Power Factor CorrectionAmalu PhilipÎncă nu există evaluări

- DC Electric Springs - A Technology For Stabilizing DC Power Distribution SystemsDocument18 paginiDC Electric Springs - A Technology For Stabilizing DC Power Distribution SystemsRémiÎncă nu există evaluări

- EDC Notes PDFDocument377 paginiEDC Notes PDFscribdcurrenttextÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space Phasor Theory and Control of Multiphase MachinesDocument16 paginiSpace Phasor Theory and Control of Multiphase MachinesvalentinmullerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gujarat Technological University: W.E.F. AY 2018-19Document3 paginiGujarat Technological University: W.E.F. AY 2018-19manish_iitrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power Quality Improvement in Grid Connected PV SystemDocument6 paginiPower Quality Improvement in Grid Connected PV SystemEditor IJTSRDÎncă nu există evaluări

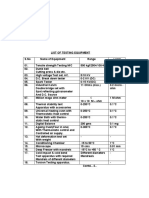

- Testing Euipments ListDocument2 paginiTesting Euipments Listshaikh mohd ziaullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar PowerDocument34 paginiSolar PowerkhoidayvangduongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exp 5Document6 paginiExp 5HR HabibÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Page of AssignmentDocument8 paginiFirst Page of Assignmentmatougabouzmila0% (1)

- Syllabus For Power Electronics and DriveDocument34 paginiSyllabus For Power Electronics and Drivearavi1979Încă nu există evaluări

- Electic Field&Electricflux AlvaranDocument4 paginiElectic Field&Electricflux AlvaranRestian Lezlie AlvaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- WecsDocument68 paginiWecsRajaraman Kannan100% (1)

- Solar Cell Parameters: WWW - Ggsy.in Training@ggsy - inDocument4 paginiSolar Cell Parameters: WWW - Ggsy.in Training@ggsy - inImran Mazumder100% (1)

- ATP Petersen Coil PracticalExerciseDocument33 paginiATP Petersen Coil PracticalExerciseGesiel SoaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partially Shaded Operation of A Grid-Tied PV SystemDocument9 paginiPartially Shaded Operation of A Grid-Tied PV SystemheanbuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit-I: Introduction of BJTDocument56 paginiUnit-I: Introduction of BJThodeegits9526Încă nu există evaluări

- Insulation Coordination Study Study CasesDocument6 paginiInsulation Coordination Study Study CasesErsi AgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clean Energy Generation, Integration and Storage (Eee-801) : Dr. Abasin Ulasyar Assistant Professor (NUST USPCAS-E)Document12 paginiClean Energy Generation, Integration and Storage (Eee-801) : Dr. Abasin Ulasyar Assistant Professor (NUST USPCAS-E)Malik Shahzeb Ali0% (1)

- An Introduction To Underwater Acoustics (2004)Document1 paginăAn Introduction To Underwater Acoustics (2004)Carlos JavierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar Power SatelliteDocument28 paginiSolar Power SatelliteInduchoodan Rajendran100% (2)

- Part2 Maxwell Ultracapacitors TechnologyAtGlanceDocument80 paginiPart2 Maxwell Ultracapacitors TechnologyAtGlanceruhulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ilya Gertsbakh Auth. Measurement Theory ForDocument157 paginiIlya Gertsbakh Auth. Measurement Theory ForauduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Line Design Based Upon Direct StrokesDocument32 paginiLine Design Based Upon Direct StrokesbasilecoqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modeling of Solar PV System Under Partial Shading Using Particle Swarm Optimization Based MPPTDocument7 paginiModeling of Solar PV System Under Partial Shading Using Particle Swarm Optimization Based MPPTAnonymous CUPykm6DZÎncă nu există evaluări

- ApuntesDocument28 paginiApuntesFrancisco RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Important Questions in RF and Microwave Engineering EC2403 EC 2403 Subject For NOVDocument2 paginiImportant Questions in RF and Microwave Engineering EC2403 EC 2403 Subject For NOVeldhosejmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surge Current Protection Using SuperconductorDocument2 paginiSurge Current Protection Using SuperconductorSaurabh Band PatilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Type Test Verification - SafePlusDocument7 paginiType Test Verification - SafePlusAnonymous hRePlgdOFrÎncă nu există evaluări

- P3T32 en M J006 ANSI Web PDFDocument426 paginiP3T32 en M J006 ANSI Web PDFBruce NationÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 0800 HVDC Plenary RashwanDocument24 pagini04 0800 HVDC Plenary RashwanDante FilhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Curves Are Used To ObtainDocument4 paginiThe Curves Are Used To Obtainnantha74Încă nu există evaluări

- Guide Spec 9395P 200-600kW UPS PDFDocument19 paginiGuide Spec 9395P 200-600kW UPS PDFabual3ezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alone, FCG-Driven High Power Microwave SystemDocument5 paginiAlone, FCG-Driven High Power Microwave SystempauljansonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Design and Performance of A Power System For The Galileo System Test Bed GSTB-V2ADocument6 paginiThe Design and Performance of A Power System For The Galileo System Test Bed GSTB-V2AAndres Rambal VecinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 19 Induction Motor Fundamentals PDFDocument37 pagini19 Induction Motor Fundamentals PDFsuchita jainÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Principles of Nuclear Energy) - Modified - AyubDocument40 pagini(Principles of Nuclear Energy) - Modified - AyubMuzammil KhalilÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Review of Commonly Used DC Arc Models PDFDocument10 paginiA Review of Commonly Used DC Arc Models PDFMrn PÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supercapacitors 130206061102 Phpapp02Document22 paginiSupercapacitors 130206061102 Phpapp02Brrijesh YadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSLF User's ManualDocument2.187 paginiPSLF User's ManualnoahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space-Based Solar PowerDocument18 paginiSpace-Based Solar PowerMuhammed Nihad PÎncă nu există evaluări

- BEE Module 1Document17 paginiBEE Module 1John crax100% (1)

- Design and Implementation of An Effective Electrical Power System For Nano Satellite 2Document7 paginiDesign and Implementation of An Effective Electrical Power System For Nano Satellite 2Mohammad Chessab MahdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voltage Controlled Current SourceDocument14 paginiVoltage Controlled Current SourceQaiser JavedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piezo Electric Transducer ReportDocument8 paginiPiezo Electric Transducer Reportأسامة عليÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECE 611 SP17 Homework 1Document3 paginiECE 611 SP17 Homework 1hanythekingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Band Theory For SolidsDocument6 paginiBand Theory For SolidsShaji ThomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of Çukurova Institute of Natural and Applied ScienceDocument227 paginiUniversity of Çukurova Institute of Natural and Applied ScienceSharmiladevy Prasanna100% (1)

- NYISO Interconnection Queue 11/30/2018Document15 paginiNYISO Interconnection Queue 11/30/2018pandorasboxofrocksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viewtenddoc PDFDocument68 paginiViewtenddoc PDFSundaresan SabanayagamÎncă nu există evaluări

- TÜV - Additional Requirements For Supplementary Rating and Qualification of Bifacial PV-modules - SNEC 2018Document29 paginiTÜV - Additional Requirements For Supplementary Rating and Qualification of Bifacial PV-modules - SNEC 2018Miguel GarzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modeling of The Solid Rotor Induction MotorDocument5 paginiModeling of The Solid Rotor Induction MotorIraqi stormÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antenna Part B QuestionsDocument2 paginiAntenna Part B QuestionsArshad MohammedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Machine Simulation ModelsDocument22 paginiMachine Simulation ModelsAshwani RanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ee8703 - Res - Unit 3Document55 paginiEe8703 - Res - Unit 3mokkai of the day videos100% (1)

- Analysis and Simulation of Photovoltaic Systems Incorporating BatDocument118 paginiAnalysis and Simulation of Photovoltaic Systems Incorporating BatDaniel Gomes JulianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NeuralNetworks One PDFDocument58 paginiNeuralNetworks One PDFDavid WeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 25510-A New Calculation For Designing Multilayer Planar Spiral Inductors PDF PDFDocument4 pagini25510-A New Calculation For Designing Multilayer Planar Spiral Inductors PDF PDFAnonymous Kti5jq5EJIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Earthing & Equi Potential BondingDocument27 paginiEarthing & Equi Potential BondingSDE BSS KollamÎncă nu există evaluări

- In the Shadow of the Moon: America, Russia, and the Hidden History of the Space RaceDe la EverandIn the Shadow of the Moon: America, Russia, and the Hidden History of the Space RaceEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (4)

- Catálogo de Pruebas Estándar IEEE para Transformadores Tipo SecoDocument83 paginiCatálogo de Pruebas Estándar IEEE para Transformadores Tipo SecoBanner Ruano100% (2)

- SteelMaster 1200WF BrochureDocument4 paginiSteelMaster 1200WF BrochureSatish VishnubhotlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Transformer DesignDocument148 paginiPractical Transformer Designعمر محمود100% (6)

- Horseshoe Curve ManualDocument10 paginiHorseshoe Curve ManualDRG_5_UÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hitachi USPV Architecture and Concepts PDFDocument103 paginiHitachi USPV Architecture and Concepts PDFdvÎncă nu există evaluări

- MIT 2016 Report of ResearchDocument44 paginiMIT 2016 Report of ResearchMuhammad SalmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- UC001 - IM Use Case 1Document15 paginiUC001 - IM Use Case 1dedie29Încă nu există evaluări

- Tnetv 901 DatasheetDocument13 paginiTnetv 901 DatasheetmadscientistatlargeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Tanuj K Khard Rev2Document12 paginiCase Study Tanuj K Khard Rev2TanujÎncă nu există evaluări

- BITS Dubai ProspectusDocument48 paginiBITS Dubai ProspectusDeepak DahiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foamaster Mo 2111Document2 paginiFoamaster Mo 2111Gustavo E Aguilar EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Project Reporting Dash Board - Rev 1Document7 paginiWeekly Project Reporting Dash Board - Rev 1Ajaya KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infra GDocument10 paginiInfra GMeynard AspaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rejection Handling ProcessDocument4 paginiRejection Handling ProcessSangeeth BhoopaalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Máquina Moer Alumina PDFDocument36 paginiMáquina Moer Alumina PDFDulce GabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surface Lift Distribution-Francisco Miguel Acevedo GonzalezDocument7 paginiSurface Lift Distribution-Francisco Miguel Acevedo GonzalezJesus DominguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAP MM Quick Guide PDFDocument222 paginiSAP MM Quick Guide PDFKhadeer AhamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- SW ReengineeringDocument40 paginiSW ReengineeringmeerasheikÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 Festool Catalog Final 72Document100 pagini06 Festool Catalog Final 72demo1967Încă nu există evaluări

- March 19, 2013 PMDocument251 paginiMarch 19, 2013 PMOSDocs2012Încă nu există evaluări

- Air Cadet Publication: FlightDocument62 paginiAir Cadet Publication: FlightMarcus Drago100% (1)

- Difference Between Hyper Threading & Multi-Core Technology PDFDocument2 paginiDifference Between Hyper Threading & Multi-Core Technology PDFsom_dutt100% (1)

- C.N.C Lathe SpecificationnDocument5 paginiC.N.C Lathe Specificationnsarfaraz023Încă nu există evaluări

- Inkt Cables CabinetsDocument52 paginiInkt Cables CabinetsvliegenkristofÎncă nu există evaluări

- A320 Oeb N°44 L:G Gear Not Downlocked PDFDocument31 paginiA320 Oeb N°44 L:G Gear Not Downlocked PDFpilote_a3200% (1)

- MGT 187 University of The Philippines Cebu: JKL BearingDocument8 paginiMGT 187 University of The Philippines Cebu: JKL BearingbutterflygigglesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10-Personnel Cost PlanningDocument52 pagini10-Personnel Cost PlanningWenny HuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ska, Monthly Report Januari 2018Document60 paginiSka, Monthly Report Januari 2018Muhammad Ma'mumÎncă nu există evaluări

- SimaPro PHDDocument1 paginăSimaPro PHDAnonymous zYW2HQlezdÎncă nu există evaluări