Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Clinical Prediction Rule To Identify Patients Likely To Responde To Lumbar Spine Stabilization Exercisess: A Randomized Controlled Validation Study

Încărcat de

SamSchroetkeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Clinical Prediction Rule To Identify Patients Likely To Responde To Lumbar Spine Stabilization Exercisess: A Randomized Controlled Validation Study

Încărcat de

SamSchroetkeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

6 | january 2014 | volume 44 | number 1 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

L

ow back pain (LBP) is

common among the general

population, with a lifetime

prevalence and point pre-

valence estimated to be greater

than 80% and 28%, respectively.

12

Although short-term outcomes are gen-

erally favorable, some patients go on to

experience long-term pain and disabil-

ity,

32,40,78

and recurrence rates are high.

17,78

Systematic reviews of various physi-

cal therapy interventions for LBP do not

provide strong support for any particu-

lar treatment approach.

2,50,51,77

One pos-

sible reason is the use of heterogeneous

samples of patients in many clinical trials

for LBP. Patients with LBP demonstrate

both etiologic and prognostic hetero-

geneity,

7,40,45

which makes it unlikely for

any single intervention to have a signi-

cant advantage over another in a general

population with LBP. Classifying patients

into more homogeneous subgroups has

been previously identied as a top re-

TSTUDY DESIGN: Randomized controlled trial.

TOBJECTIVE: To determine the validity of a

previously suggested clinical prediction rule (CPR)

for identifying patients most likely to experience

short-term success following lumbar stabilization

exercise (LSE).

TBACKGROUND: Although LSE is commonly

used by physical therapists in the management

of low back pain, it does not seem to be more

efective than other interventions. A 4-item CPR

for identifying patients most likely to benet from

LSE has been previously suggested but has yet to

be validated.

TMETHODS: One hundred ve patients with

low back pain underwent a baseline examination

to determine their status on the CPR (positive or

negative). Patients were stratied by CPR status

and then randomized to receive an LSE program

or an intervention consisting of manual therapy

(MT) and range-of-motion/exibility exercises.

Both interventions included 11 treatment sessions

delivered over 8 weeks. Low back painrelated

disability was measured by the modied version of

the Oswestry Disability Index at baseline and upon

completion of treatment.

TRESULTS: The statistical signicance for the

2-way interaction between treatment group and

CPR status for the level of disability at the end

of the intervention was P = .17. However, among

patients receiving LSE, those with a positive CPR

status experienced less disability by the end of

treatment compared with those with a nega-

tive CPR status (P = .02). Also, among patients

with a positive CPR status, those receiving LSE

experienced less disability by the end of treatment

compared with those receiving MT (P = .03). In

addition, there were main efects for treatment and

CPR status. Patients receiving LSE experienced

less disability by the end of treatment compared to

patients receiving MT (P = .05), and patients with

a positive CPR status experienced less disability

by the end of treatment compared to patients with

a negative CPR status, regardless of the treatment

received (P = .04). When a modied version of

the CPR (mCPR) containing only the presence of

aberrant movement and a positive prone instability

test was used, a signicant interaction with treat-

ment was found for nal disability (P = .02). Of the

patients who received LSE, those with a positive

mCPR status experienced less disability by the end

of treatment compared to those with a negative

mCPR status (P = .02), and among patients with

a positive mCPR status, those who received LSE

experienced less disability by the end of treatment

compared to those who received MT (P = .005).

TCONCLUSION: The previously suggested CPR

for identifying patients likely to benet from LSE

could not be validated in this study. However, due

to its relatively low level of power, this study could

not invalidate the CPR, either. A modied version

of the CPR that contains only 2 items may possess

a better predictive validity to identify those most

likely to succeed with an LSE program. Because

this modied version was established through post

hoc testing, an additional study is recommended

to prospectively test its predictive validity.

TLEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Prognosis, level 1b. J

Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014;44(1):6-18. Epub 21

November 2013. doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.4888

TKEY WORDS: lumbar spine, manual therapy

1

Department of Physiotherapy, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel.

2

Bat-Yamon Physical Therapy Clinic, Clalit Health Services, Israel.

3

Giora Physical Therapy Clinic, Clalit Health

Services, Israel.

4

Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. This study was approved by the Helsinki

Committee of Clalit Health Services. The authors certify that they have no afliations with or nancial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct nancial interest

in the subject matter or materials discussed in the article. Address correspondence to Dr Alon Rabin, Ariel University, Department of Physiotherapy, Kiryat Hamada, PO Box 3,

Ariel, Israel. E-mail: alonrabin@gmail.com T Copyright 2014 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy

ALON RABIN, DPT, PhD

1

ANAT SHASHUA, BPT, MS

2

KOBY PIZEM, BPT

3

RUTHY DICKSTEIN, PT, DSc

4

GALI DAR, PT, PhD

4

A Clinical Prediction Rule to Identify

Patients With Low Back Pain Who Are

Likely to Experience Short-Term Success

Following Lumbar Stabilization Exercises:

A Randomized Controlled Validation Study

[ RESEARCH REPORT ]

44-01 Rabin.indd 6 12/17/2013 5:18:33 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 44 | number 1 | january 2014 | 7

search priority,

6

and, in fact, more recent

research has suggested that matching pa-

tients with interventions based on their

specic clinical presentation may yield

improved clinical outcomes.

8,10,15,27,47

Structural as well as functional

impairments, such as decreased and

delayed activation of the transversus ab-

dominis and atrophy of the lumbar mul-

tidus,

25,34,37,48,69,80

have been identied

among patients with LBP. These impair-

ments may result in a reduction in spinal

stifness

82

and possibly render the spine

more vulnerable to excessive deforma-

tion and pain. Lumbar stabilization ex-

ercises (LSE) attempt to address these

impairments by retraining the proper

activation and coordination of trunk

musculature.

58,64

Stabilization exercises

are widely used by physical therapists in

the management of LBP.

8,11,22,24,35,44,49,50,62,65

Although some evidence exists to support

the remediating efects of LSE on some

of the muscle impairments identied in

patients with LBP,

36,73,74

the clinical ef-

cacy of this intervention seems to vary.

When compared to sham or no interven-

tion, LSE appears to be advantageous

22,65

;

however, when compared to other exer-

cise interventions or to manual therapy

(MT), no denitive advantage has been

ascertained.

11,24,35,44,49,50,62,75

In light of the variable clinical suc-

cess of LSE and in accordance with the

aforementioned need to classify patients

who have LBP into more homogeneous

subgroups, Hicks et al

33

suggested a clini-

cal prediction rule (CPR) to specically

identify patients with LBP who are likely

to exhibit short-term improvement with

LSE. Four variables were found to pos-

sess the greatest predictive power for

treatment success: (1) age less than 40

years, (2) average straight leg raise (SLR)

of 91 or greater, (3) the presence of aber-

rant lumbar movement, and (4) a positive

prone instability test.

33

When at least 3

of the 4 variables were present, the posi-

tive likelihood ratio for achieving a suc-

cessful outcome was 4.0, increasing the

probability of success from 33% to 67%.

33

The study by Hicks et al

33

comprises the

rst stage in establishing a CPR, the deri-

vation stage.

4,14,55

Following derivation, a

CPR must be validated, that is, shown to

consistently predict the outcome of inter-

est in a separate and preferably prospec-

tive investigation.

26

Given its preliminary

nature, and because CPRs do not typi-

cally perform as well on new samples of

patients,

21,30,67,68

modication of the CPR

may also be necessary to achieve satisfac-

tory predictive validity. Once validated,

CPRs can move into the nal stage of

their determination, which includes an

investigation into their impact on clini-

cal practice (impact analysis).

4,14,55

Validation of the CPR for LSE re-

quires a randomized controlled trial in

which patients with a diferent status on

the CPR (positive or negative) undergo

an LSE program, as well as a comparison

intervention.

4

The use of a comparison

intervention is important to determine

whether the CPR can truly identify pa-

tients who will benet specically from

LSE, as opposed to patients who have a

favorable prognosis irrespective of the

treatment received.

66

Finally, to validate

the CPR in the most clinically meaning-

ful manner, we believe that the compari-

son intervention should be considered a

viable alternative to LSE, rather than a

sham or an inert intervention.

Manual therapy is an intervention fre-

quently used by physical therapists in the

management of patients with LBP

39,46,56

and is recommended by several clinical

practice guidelines and systematic reviews

for the management of acute, subacute,

and chronic LBP.

1,9,19,76

These factors, com-

bined with the fact that LSE programs

have previously demonstrated varied

levels of success compared to MT,

11,24,50,62

suggest that MT may be a suitable com-

parison intervention for testing the validi-

ty of the CPR. In contrast to its use among

heterogeneous samples,

11,24,50,62

LSE

should demonstrate a clearer advantage

among patients with LBP who also satisfy

the CPR, if the CPR accurately identies

the correct target patient population.

The purpose of this investigation was

to determine the validity of, or to possibly

modify, the previously suggested CPR for

identifying patients most likely to benet

from LSE. We hypothesized that among

patients receiving LSE, those with a posi-

tive CPR status would exhibit a better

outcome compared to those with a nega-

tive CPR status. We also hypothesized

that among patients with a positive CPR

status, those who received LSE would ex-

hibit a better outcome compared to those

who received MT.

METHODS

Patients

O

ne hundred ve patients diag-

nosed with LBP and referred to

physical therapy at 1 of 5 outpa-

tient clinics of Clalit Health Services in

the Tel-Aviv metropolitan area, Israel,

were recruited for this study. Subjects

were included if they were 18 to 60 years

of age, had a primary complaint of LBP

with or without associated leg symptoms

(pain, paresthesia), and had a minimum

score of 24% on the Hebrew version of

the modied Oswestry Disability Index

(MODI) outcome measure. Patients

were excluded if they presented with a

history suggesting any red ags (eg, ma-

lignancy, infection, spine fracture, cauda

equina syndrome); 2 or more signs sug-

gesting lumbar nerve root compression,

such as decreased deep tendon reexes,

myotomal weakness, decreased sensation

in a dermatomal distribution, or a posi-

tive SLR, crossed SLR, or femoral nerve

stretch test; or a history of corticosteroid

use, osteoporosis, or rheumatoid arthri-

tis. Patients were also excluded if they

were pregnant, received chiropractic

or physical therapy care for LBP in the

preceding 6 months, could not read or

write in the Hebrew language, or had a

pending legal proceeding associated with

their LBP. Prior to participation, all pa-

tients signed an informed consent form

approved by the Helsinki Committee of

Clalit Health Services.

Therapists

Sixteen physical therapists were involved

44-01 Rabin.indd 7 12/17/2013 5:18:35 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

8 | january 2014 | volume 44 | number 1 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

[ RESEARCH REPORT ]

in the study. Eleven therapists, with be-

tween 4 and 12 years of experience in

outpatient physical therapy patient care,

provided treatment, and 5 therapists,

with between 13 to 25 years of experi-

ence, performed baseline and follow-

up evaluations. Prior to beginning the

study, all participating therapists under-

went two 4-hour sessions in which the

rationale and protocol of the study were

presented and the examination and treat-

ment procedures were demonstrated and

practiced. Therapists had to pass a writ-

ten examination of the study procedures

prior to data collection. Finally, each

therapist received a manual describing

treatment and evaluation procedures,

based on the therapists role in the study

(treatment or evaluation). Therapists in-

volved in treating patients were unaware

of the concept of the CPR throughout the

study, to avoid bias from this knowledge

during treatment. All treating therapists

provided both treatments of the study

(LSE and MT).

Procedure

After giving consent, patients completed

a baseline examination that included de-

mographic information, an 11-point (0-

10) numeric pain rating scale (NPRS),

on which 0 was no pain and 10 was

the worst imaginable pain, the Hebrew

version of the MODI,

3,28

and the Hebrew

version of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs

Questionnaire.

38,79

In addition, the his-

tory of the present and any past LBP

was documented, followed by a physical

examination.

The physical examination included a

neurological screen to rule out lumbar

nerve root compression; lumbar active

motion, during which the presence of ab-

errant movement, as dened by Hicks et

al,

33

was determined; bilateral SLR range

of motion; segmental mobility of the lum-

bar spine; and the prone instability test.

The patients status on the CPR (positive

or negative) was established based on the

ndings of the physical examination.

Examiners who performed the base-

line examinations, as well as examiners

who screened patients for eligibility to

participate in the study, were blinded to

the intervention allocation of the patients.

Reliability

The reliability of the individual physical

examination items comprising the CPR,

as well as that of the entire CPR, has been

reported previously.

60

In that study,

60

the

interrater reliability for determining CPR

status was excellent ( = 0.86), and the

interrater reliability of each of the items

comprising the CPR ranged from moder-

ate to substantial ( = 0.64-0.73).

60

Randomization

At the conclusion of the physical exami-

nation, each patient was randomized to

receive LSE or MT. Randomization was

based on a computer-generated list of

random numbers, stratied by CPR status

to ensure that adequate numbers of pa-

tients with a positive and a negative CPR

status would be included in each interven-

tion group. The list was kept by a research

assistant who was not involved in patient

recruitment, examination, or treatment.

Intervention

Patients in both groups received 11 treat-

ment sessions over an 8-week period.

Each patient was seen twice a week dur-

ing the rst 4 weeks, then once a week

for 3 additional weeks. A 12th session

(usually on the eighth week) consisted

of a nal evaluation. The total number

of sessions (12) matched the maximum

number of physical therapy visits allowed

annually per condition under the policy

of the Clalit Health Services health main-

tenance organization, which covered all

patients participating in the study. Pa-

tients in both groups were prescribed a

home exercise program consistent with

their treatment group; however, no at-

tempt was made to monitor patients

compliance with the home exercise

program.

Lumbar Stabilization Exercises

The LSE program was largely based on

the program described by Hicks et al,

33

with a few minor changes in the order of

the exercises and a few additional levels

of difculty for some of the exercises. Pa-

tients were initially educated about the

structure and function of the trunk mus-

culature, as well as common impairments

in these muscles among patients with

LBP. Patients were then taught to per-

form an isolated contraction of the trans-

versus abdominis and lumbar multidus

through an abdominal drawing-in ma-

neuver (ADIM) in the quadruped, stand-

ing, and supine positions.

63,64,69,71,73

Once

a proper ADIM was achieved (most likely

by the second or third visit), additional

loads were placed on the spine through

various upper extremity, lower extremity,

and trunk movement patterns. Exercises

were performed in the quadruped, sidely-

ing, supine, and standing positions, with

the goal of recruiting a variety of trunk

muscles.

18,53,54

In each position, exercises

were ordered by their level of difculty,

and patients progressed from one exer-

cise to the next after satisfying specic

predetermined criteria. In the seventh

treatment session, functional movement

patterns were incorporated into the

training program while performing an

ADIM and maintaining a neutral lumbar

spine. This stage, which was not includ-

ed in the derivation study, was added to

the program because it has been recom-

mended by others.

22,58,62

The exercises in

each stage of the LSE program, as well as

the specic criteria for progression from

one exercise to the next, are outlined in

APPENDIX A (available at www.jospt.org).

Manual Therapy

The MT intervention included several

thrust and nonthrust manipulative tech-

niques directed at the lumbar spine that

have been used previously with some

degree of success in various groups with

LBP.

10,15,20,59

In addition, manual stretch-

ing of several hip and thigh muscles was

performed, as exibility of the lower ex-

tremity is purported to protect the spine

from excessive strain.

54

Finally, active

range-of-motion and stretching exercis-

es were added to the program, as these

44-01 Rabin.indd 8 12/17/2013 5:18:36 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 44 | number 1 | january 2014 | 9

are commonly prescribed in combina-

tion with MT to maintain or improve the

mobility gains resulting from the manual

procedures.

10,15,20,47

The exercises included

were selected to minimize trunk muscle

activation and to avoid duplication be-

tween the 2 interventions.

All manual procedures and exercises

were prescribed based on the clinical

judgment of the treating therapist; how-

ever, each session could include up to 3

manual techniques, 1 of which had to be

a thrust manipulative technique directed

at the lumbar spine, and an additional

technique that had to include a manual

stretch of a lower extremity muscle. The

third technique, as well as the comple-

mentary range-of-motion/exibility ex-

ercises, was given at the discretion of the

treating therapist. The MT techniques, as

well as all exercises used in the MT proto-

col, are described in APPENDIX B (available

at www.jospt.org).

Evaluation

The MODI served as the primary out-

come measure in this investigation. The

MODI is scored from 0 to 100 and has a

minimal clinically important diference

(MCID) of 10 points among patients with

LBP.

57

The secondary outcome measure

was the NPRS, which has an MCID of 2

points among patients with LBP.

16

Both

measures were administered before the

beginning of treatment and immediately

after the last treatment session by an in-

vestigator not involved in patient care.

Sample Size

Sample size was calculated to detect a be-

tween-group diference of 12 points in the

nal score of the MODI, based on the in-

teraction between treatment group (LSE

versus MT) and CPR status (positive ver-

sus negative), with an alpha level of .05

and a power of 70%. Based on a 16-point

standard deviation, it was determined

that 20 patients were needed in each cell.

Pilot data suggested that the prevalence

of patients with a positive status on the

CPR was approximately 33%. Therefore,

it was estimated that 120 patients would

be necessary to include 40 patients with

a positive CPR status; however, 40 such

patients were included after 105 patients

were recruited, and recruitment was

stopped at that point.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequen-

cy counts for categorical variables and

measures of central tendency and dis-

persion for continuous variables, were

used to summarize the data. All baseline

variables were assessed for normal distri-

bution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Base-

line variables were compared between

treatment groups (LSE versus MT), CPR

status (positive versus negative), and

the resulting 4 subgroups using a 2-way

analysis of variance and chi-square tests

for continuous and categorical variables,

respectively.

The primary aim of the study was

tested using 2 separate analyses of cova-

riance (ANCOVAs), with the nal MODI

score serving as the dependent variable in

1 model and the nal NPRS score serving

as the dependent variable in the second

model. In both models, treatment group

and CPR status served as independent

variables, and the baseline MODI score

(or baseline NPRS score) was used as

a covariate. The residuals of all models

were tested for violations of the ANCOVA

assumptions and for outliers. The main

efects of treatment group and CPR sta-

tus, as well as the 2-way interaction be-

tween these factors on the nal MODI

and NPRS scores, were evaluated. The a

priori level of signicance for these analy-

ses was P.05. Two pairwise comparisons

were planned following the ANCOVA: (1)

a comparison of diferences between pa-

tients with a positive CPR receiving LSE

and those with a negative CPR receiving

LSE, and (2) a comparison of diferences

between patients with a positive CPR

receiving LSE and those with a positive

CPR receiving MT. These 2 comparisons

were deemed the most relevant for the

purpose of validating the CPR, as both

included a comparison between patients

receiving a matched intervention (CPR-

positive patients receiving LSE) and

patients receiving an unmatched inter-

vention (either CPR-negative patients

receiving LSE or CPR-positive patients

receiving MT).

The individual items of the CPR, as

well as diferent combinations of these

items, were similarly tested to identify

whether any such combination would

enhance the predictive validity of the

original version. Finally, the outcome was

also dichotomized as successful or unsuc-

cessful based on a previously established

cutof threshold of 50% reduction in the

baseline score of the MODI.

33

The pro-

portion of patients achieving a success-

ful outcome was compared among the

resulting subgroups (LSE CPR+, LSE

CPR, MT CPR+, and MT CPR) using

chi-square analysis.

An intention-to-treat approach was

performed for all analyses by using mul-

tiple imputations for any missing val-

ues of the 2 outcome measures (MODI,

NPRS). First, Littles missing completely

at random test was performed to test the

hypothesis that missing values were ran-

domly distributed. If this hypothesis could

not be rejected, expectation maximization

was used to predict missing values. A per-

protocol analysis was performed as well.

All statistical analyses were performed us-

ing the JMP Version 10 statistical package

(SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), as well as

the SPSS Version 19 statistical package

(SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

F

ive hundred thirty-one poten-

tial candidates were screened for

eligibility between March 2010 and

April 2012. Two hundred ninety-seven pa-

tients did not meet the inclusion criteria,

and another 129 declined participation.

The remaining 105 patients were admit-

ted into the study. Forty patients had a

positive CPR status, whereas 65 had a

negative status. Forty-eight patients were

randomized to the LSE group, whereas 57

patients were randomized to receive MT.

All patients underwent treatment accord-

44-01 Rabin.indd 9 12/17/2013 5:18:37 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

10 | january 2014 | volume 44 | number 1 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

[ RESEARCH REPORT ]

ing to their allocated treatment group.

Sixteen patients did not complete the

LSE intervention, and 8 patients did not

complete the MT intervention (P = .02).

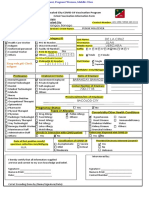

FIGURE 1 presents patient recruitment and

retention throughout the study.

TABLE 1 presents baseline demographic,

history, and self-reported variables for all

groups and subgroups. All baseline vari-

ables were normally distributed, with the

exception of body mass index and dura-

tion of LBP. Log transformations were

thus performed on body mass index and

duration of LBP, resulting in a better dis-

tribution pattern. As a result, the geomet-

ric mean with 95% condence interval is

reported for these variables, as opposed

to mean SD for all other baseline vari-

ables (TABLE 1). No baseline diferences

were noted between the diferent groups

and subgroups other than for age. Pa-

tients with a positive CPR status were

younger than patients with a negative

CPR status (P = .0006). This diference

was expected, as 1 of the items comprising

the CPR is being less than 40 years of age.

Therefore, we did not correct our model

to account for this expected diference.

Littles "missing completely at ran-

dom" test indicated that the hypothesis

that nal MODI and NPRS scores were

randomly missing could not be rejected

(P = .76 for the MODI and P = .52 for the

NPRS). Therefore, expectation maximi-

zation was used to replace missing values.

Completers Versus Noncompleters

All baseline demographic, history, and

self-reported variables were compared

between patients who completed the

intervention (completers, n = 81) and

patients who dropped out prior to com-

pleting the intervention (noncompleters,

n = 24) using Wilcoxon and Fisher ex-

act tests for continuous and categorical

variables, respectively. Noncompleters

exhibited a higher baseline score on

the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Question-

naire physical activity subscale versus

completers (17.2 versus 15.1, P = .04).

Noncompleters also had a lower level

of education compared to completers

(P = .03). No other diferences were

detected between the completers and

noncompleters.

Analysis by Intention to Treat

The baseline and nal MODI and NPRS

scores for each treatment group and sub-

group are summarized in TABLE 2. When

assessing nal disability level, the statisti-

cal level of signicance for the 2-way in-

teraction between treatment group and

CPR status was P = .17. A main efect was

detected for treatment (P = .05), which

indicated that patients receiving LSE

experienced less disability by the end

of treatment compared to the patients

who received MT. A main efect was also

detected for CPR status (P = .04), indi-

cating that patients with a positive CPR

status experienced less disability by the

end of treatment compared to those with

a negative CPR status, regardless of the

treatment received. The 2 preplanned

pairwise comparisons indicated that (1)

among patients receiving LSE, those with

a positive CPR status experienced less dis-

ability at the end of the intervention com-

pared to those with a negative CPR status

(P = .02); and (2) among patients with a

positive CPR status, those receiving LSE

experienced less disability by the end

of treatment compared to those receiv-

ing MT (P = .03). The change in MODI

between baseline and the end of treat-

ment for the 4 subgroups is represented

in FIGURE 2. No interactions or main ef-

fects were noted for pain (P>.26). TABLE 3

pre sents the adjusted nal disability and

pain scores for all groups and subgroups,

and TABLE 4 presents the diferences in -

nal disability and pain among the difer-

ent groups and subgroups.

Screened for eligibility, n = 531

Randomized, n = 105

Lumbar stabilization exercises,

n = 48

Excluded, n = 297:

MODI <24%, n = 151

Prior physical therapy, n = 28

Nerve root compression, n = 26

Pending legal proceeding, n = 24

Did not meet other inclusion

criteria, n = 68

Declined participation, n = 129

Manual therapy, n = 57

8-wk follow-up, n = 32

16 dropped out

8-wk follow-up, n = 49

8 dropped out

Analyzed, n = 48

CPR+, n = 18

Analyzed, n = 57

CPR, n = 30 CPR+, n = 22 CPR, n = 35

FIGURE 1. Flow diagram of participant recruitment and retention. Abbreviations: CPR, clinical prediction rule;

MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index.

44-01 Rabin.indd 10 12/17/2013 5:18:38 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 44 | number 1 | january 2014 | 11

The proportion of patients who

achieved a successful outcome, dened

as a reduction of at least 50% in disability

as measured by the MODI, did not difer

among the 4 subgroups (P = .31) (FIGURE 3).

When examining the interaction of

treatment group with each of the indi-

vidual items comprising the CPR on -

nal disability, no signicant efects were

noted (aberrant movement, P = .07; prone

instability test, P = .16; age less than 40

years, P = .72; SLR of 91 or greater, P =

.79). However, when combining the pres-

ence of aberrant movement and a positive

prone instability test (n = 44), a signi-

cant 2-way interaction between treatment

group and the modied version of the CPR

(mCPR) was found for nal disability (P

= .02). When the 2 pairwise comparisons

were repeated using the mCPR, ndings

indicated that (1) among patients receiv-

ing LSE, those with a positive mCPR sta-

tus (n = 20) experienced less disability by

the end of treatment compared to those

with a negative mCPR status (n = 28, P =

.02); and (2) among patients with a posi-

tive mCPR status, those receiving LSE (n

= 20) experienced less disability by the

end of treatment compared to those re-

ceiving MT (n = 24, P = .005). Unlike the

original version of the CPR, the mCPR

did not demonstrate a main efect for -

nal disability (P = .27). No 2-way interac-

tion or main efects were noted for nal

pain level when using the mCPR (P>.09).

TABLE 5 presents the adjusted nal disabil-

ity and pain scores of the diferent groups

and subgroups based on the mCPR, and

TABLE 6 presents the diferences in nal

disability and pain among the groups and

subgroups based on the mCPR.

Finally, the proportion of patients

achieving a successful outcome did not

difer between the subgroups based on

mCPR status (P = .30) (FIGURE 4).

Per-Protocol Analysis

Similar to analysis by intention to treat,

TABLE 1 Baseline Demographic, History, and Self-Report Variables for All Groups

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CPR, patients with a negative status on the clinical prediction rule; CPR+, patients with a positive status on the clini-

cal prediction rule; FABQ-PA, Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire physical activity subscale; FABQ-W, Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire work subscale;

LBP, low back pain; LSE, patients treated with lumbar stabilization exercises; MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index; MT, patients treated with manual

therapy; NPRS, numeric pain rating scale.

*Values are mean SD.

CPR greater than CPR+ (P = .0006).

Values are mean (95% condence interval).

Numbers provided when data not available on all patients.

Characteristic LSE (n = 48) MT (n = 57) CPR+ (n = 40) CPR (n = 65)

LSE CPR+

(n = 18)

LSE CPR

(n = 30)

MT CPR+

(n = 22)

MT CPR

(n = 35)

Sex (female), n (%) 25 (52.1) 31 (54.4) 22 (55.0) 34 (52.3) 10 (55.6) 15 (50.0) 12 (54.5) 19 (54.3)

Age, y*

38.3 10.5 35.5 9.1 32.8 7.5 39.2 10.3 32.7 7.4 41.6 10.7 32.8 7.7 37.2 9.6

BMI, kg/m

2

24.4 (22.9, 25.9) 25.8 (24.3, 27.3) 24.2 (22.6, 25.9) 25.9 (24.7, 27.3) 22.9 (20.7, 25.4) 25.9 (24.0, 27.9) 25.6 (23.3, 28.1) 26.0 (24.3, 27.8)

Education, n (%)

Less than high school 2 (4.2) 0 (0) 0 (0) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) 2 (6.7) 0 (0) 0 (0)

High school 21 (43.7) 15 (26.3) 9 (22.5) 27 (41.5) 5 (27.8) 16 (53.3) 4 (18.2) 11 (31.4)

Some postsecondary 8 (16.7) 15 (26.3) 9 (22.5) 14 (21.5) 3 (16.7) 5 (16.7) 6 (27.3) 9 (25.7)

Bachelor 13 (27.1) 17 (29.8) 18 (45.0) 12 (18.5) 8 (44.4) 5 (16.7) 10 (45.5) 7 (20.0)

Master 3 (6.2) 9 (15.8) 4 (10.0) 8 (12.3) 2 (11.1) 1 (3.3) 2 (9.0) 7 (20.0)

Doctorate 1 (2.1) 1 (1.8) 0 (0) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) 1 (3.3) 0 (0) 1 (2.8)

Work status (employed

),

n (%)

38/43 (88.4) 41/53 (77.4) 28/36 (77.8) 51/60 (85.0) 13/16 (81.3) 25/27 (92.6) 15/20 (75.0) 26/33 (78.8)

Smoker, n (%)

16/44 (36.4) 11/53 (20.8) 14/36 (38.9) 13/61 (21.3) 8/16 (50.0) 8/28 (28.6) 6/20 (30.0) 5/33 (15.2)

Duration (days since

onset)

58.7 (41.8, 82.4) 67.4 (48.9, 92.9) 63.8 (44.2, 92.2) 62.0 (46.5, 82.7) 52.0 (30.5, 88.6) 66.3 (43.6, 101.0) 78.4 (47.3, 130.0) 57.9 (39.1, 85.9)

Use of analgesics, n (%)

22/42 (52.4) 32/53 (60.4) 23/36 (63.9) 31/59 (52.5) 9/16 (56.3) 13/26 (50.0) 14/20 (70.0) 18/33 (54.6)

Past LBP, n (%)

34/48 (70.8) 35/56 (62.5) 27/39 (69.2) 42/65 (64.6) 13/18 (72.2) 21/30 (70.0) 14/21 (66.7) 21/35 (60.0)

Symptoms below knee,

n (%)

14 (29.2) 16 (28.1) 8 (20.0) 22 (33.8) 2 (11.1) 12 (40.0) 6 (27.3) 10 (28.6)

NPRS (0-10)* 4.9 1.7 5.3 1.7 4.9 1.7 5.3 1.7 4.4 1.7 5.2 1.6 5.2 1.6 5.4 1.8

MODI (0-100)* 37.8 10.6 37.6 12.5 40.0 12.8 36.3 10.6 37.8 9.4 37.7 11.4 41.8 15.0 35.0 9.9

FABQ-PA (0-24)* 16.2 4.4 15.1 4.9 14.9 5.3 16.0 4.3 15.9 4.3 16.3 4.6 14.1 5.8 15.7 4.2

FABQ-W (0-42)* 18.1 9.9 19.4 10.3 19.9 10.5 18.1 9.9 18.9 11.0 17.6 9.4 20.7 10.3 18.6 10.4

44-01 Rabin.indd 11 12/17/2013 5:18:39 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

12 | january 2014 | volume 44 | number 1 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

[ RESEARCH REPORT ]

there was no 2-way interaction between

CPR status and treatment on nal disabil-

ity (P = .14). In addition, a main efect was

retained for CPR status on nal disability

(P = .04), indicating that patients with a

positive CPR status experienced less dis-

ability by the end of treatment compared

to patients with a negative CPR status,

regardless of the treatment received. No

main efect was noted for treatment (P =

.06). The preplanned pairwise compari-

sons indicated that (1) among all patients

receiving LSE, those with a positive CPR

status experienced less disability by the

end of treatment compared to those with

a negative CPR status (P = .02); and (2)

among patients with a positive CPR sta-

tus, those receiving LSE experienced less

disability by the end of treatment com-

pared to those receiving MT (P = .03).

No 2-way interaction or main efect was

noted for pain (P>.21). Chi-square analy-

sis indicated that the proportion of pa-

tients achieving a successful outcome was

greater among patients with a positive

CPR status compared to patients with

a negative CPR status, regardless of the

treatment received (P = .04).

The 2-way interaction between treat-

ment group and the mCPR on nal dis-

ability was retained in the per-protocol

analysis (P = .02). The preplanned pair-

wise comparisons indicated that (1)

among patients receiving LSE, those

with a positive mCPR status experienced

less disability at the conclusion of the

intervention compared to those with a

negative mCPR status (P = .03); and (2)

among patients with a positive mCPR sta-

tus, those receiving LSE experienced less

disability at the conclusion of the inter-

vention compared to those receiving MT

(P = .006). No 2-way interaction or main

efect was noted for pain level when us-

ing the mCPR (P>.13). Finally, although a

greater proportion of patients with a posi-

tive mCPR receiving LSE achieved a suc-

cessful outcome compared to the other 3

subgroups, this diference was not signi-

cant (P = .17).

DISCUSSION

T

he previously suggested CPR

for predicting a successful outcome

following LSE

33

could not be vali-

TABLE 2

Baseline and Final Disability (MODI) and Pain

(NPRS) Scores for All Groups and Subgroups*

Abbreviations: CPR, patients with a negative status on the clinical prediction rule; CPR+, patients

with a positive status on the clinical prediction rule; LSE, patients treated with lumbar stabilization

exercises; MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index; MT, patients treated with manual therapy;

NPRS, numeric pain rating scale.

*Values are mean SD and are based on intention-to-treat analysis.

Group Baseline MODI (0-100) Final MODI (0-100) Baseline NPRS (0-10) Final NPRS (0-10)

LSE (n = 48) 37.8 10.6 16.1 11.2 4.9 1.7 2.4 1.8

MT (n = 57) 37.6 12.5 20.2 16.0 5.3 1.7 3.1 2.5

CPR+ (n = 40) 40.0 12.8 16.6 17.5 4.9 1.7 2.6 2.4

CPR (n = 65) 36.3 10.6 19.4 11.5 5.3 1.7 2.9 2.2

LSE CPR+ (n = 18) 37.8 9.4 10.7 9.8 4.4 1.7 1.9 1.6

LSE CPR (n = 30) 37.7 11.4 19.4 10.8 5.2 1.6 2.7 1.9

MT CPR+ (n = 22) 41.8 15.0 21.5 20.9 5.2 1.6 3.1 2.8

MT CPR (n = 35) 35.0 9.9 19.4 12.3 5.4 1.8 3.1 2.4

TABLE 3

Baseline Adjusted Final Disability

(MODI) and Pain (NPRS) Among the

Different Groups and Subgroups*

Abbreviations: CPR, patients with a negative status on the clinical prediction rule; CPR+, patients

with a positive status on the clinical prediction rule; LSE, patients treated with lumbar stabilization

exercises; MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index; MT, patients treated with manual therapy;

NPRS, numeric pain rating scale.

*Values are mean (95% condence interval) and are provided based on intention-to-treat analysis.

Group MODI (0-100) NPRS (0-10)

LSE (n = 48) 15.0 (11.4, 18.6) 2.5 (1.9, 3.1)

MT (n = 57) 20.0 (16.7, 23.3) 3.0 (2.4, 3.5)

CPR+ (n = 40) 14.9 (11.0, 18.8) 2.7 (2.1, 3.4)

CPR (n = 65) 20.1 (17.1, 23.1) 2.8 (2.3, 3.3)

LSE CPR+ (n = 18) 10.7 (4.9, 16.4) 2.4 (1.4, 3.3)

LSE CPR (n = 30) 19.3 (14.9, 23.8) 2.6 (1.9, 3.4)

MT CPR+ (n = 22) 19.1 (13.9, 24.4) 3.0 (2.2, 3.9)

MT CPR (n = 35) 20.9 (16.7, 25.0) 2.9 (2.2, 3.6)

0

5

10

Baseline

LSE CPR+ LSE CPR

M

O

D

I

S

c

o

r

e

,

%

Final

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

MT CPR+ MT CPR

FIGURE 2. Change in disability from baseline to the

end of treatment for the 4 subgroups. Abbreviations:

LSE CPR, patients with a negative status on

the clinical prediction rule treated with lumbar

stabilization exercises; LSE CPR+, patients with a

positive status on the clinical prediction rule treated

with lumbar stabilization exercises; MODI, modied

Oswestry Disability Index; MT CPR, patients with a

negative status on the clinical prediction rule treated

with manual therapy; MT CPR+, patients with a

positive status on the clinical prediction rule treated

with manual therapy.

44-01 Rabin.indd 12 12/17/2013 5:18:41 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 44 | number 1 | january 2014 | 13

dated in our investigation. Nevertheless,

we believe the CPR may hold promise in

identifying patients most likely to experi-

ence success following LSE. Despite the

absence of a CPR-by-treatment interac-

tion, the 2 pairwise comparisons most

relevant for validating the CPR indicated

that, by the end of treatment, patients

with a positive CPR status who received

LSE (a matched intervention) experi-

enced less disability compared to those

with a negative CPR status receiving

LSE or to patients with a positive CPR

status receiving MT (an unmatched in-

tervention). Furthermore, efect sizes for

both of these comparisons were very close

to the MCID of the MODI (10 points),

and the lower bounds of the 95% con-

dence intervals were above zero (TABLE 4).

The extra noise created by the multiple

computations of the ANCOVA might

have prevented a signicant CPR-by-

treatment interaction efect, despite the

consistent advantage for patients with a

positive CPR treated with LSE.

It seems, therefore, that the inability

to validate the CPR in this study is most

likely related to its level of power. Our

a priori sample-size calculation was de-

signed to detect a 12-point diference in

the MODI, with = .05 and a power of

70%. Therefore, it could be argued that

our study was somewhat underpowered.

However, based on our ndings, 314

patients would have been required to

achieve 80% power for detecting an in-

teraction between treatment group and

CPR status, a sample size that was un-

realistic under the circumstances of the

present study. We therefore believe that,

although our results cannot validate the

CPR, they do not invalidate it but, in fact,

seem to imply its potential. It is not un-

reasonable to assume that the CPR in its

current form may still be able to indicate

which patients would most likely succeed

with LSE.

Among other potential reasons for

the inability to validate a CPR are dif-

ferences in sample characteristics, in the

application of the CPR itself, in the ad-

ministration of the intervention, and in

the denition of the outcome between the

derivation and validation studies. With

regard to sample characteristics, the in-

clusion/exclusion criteria in the current

study were fairly similar to those of the

derivation study,

33

which resulted in rela-

tively similar samples. However, patients

in the current study demonstrated a high-

er level of disability at baseline (MODI

score, 37% versus 29% in the derivation

study

33

) and a somewhat longer duration

of symptoms (68 versus 40 days). The

longer duration of LBP in the current

sample could have had a negative efect

on the overall prognosis

32,40,72

; however,

this efect was not expected to difer be-

tween the treatment groups or subgroups.

As for the application of the CPR it-

self, the sample of the current study in-

cluded a higher proportion of patients

with a positive CPR status compared to

the derivation study (38% versus 28%).

33

A likely reason for this diference is the

younger age of our sample (37 versus 42

years). Another possible reason is the

higher prevalence of a positive prone

instability test in our study (71% versus

52% in the derivation study

33

). Because

we used the same testing technique and

rating criteria as outlined by Hicks et al,

33

we cannot explain the diference in prev-

alence rates of a positive prone instability

test. In any event, we do not believe that

the higher rate of a positive CPR status in

our study was likely to hinder the ability

to validate the CPR.

The LSE program used in the current

study was very similar to that used in the

derivation study. In addition, the criteria

for dichotomizing the outcomes as suc-

cess or failure were identical to those

used in the derivation study.

33

Therefore,

we do not believe these factors would

likely explain the inability to validate the

CPR, either.

Finally, the inability to validate the

CPR may be related to the comparison

intervention used in the current study.

TABLE 4

Baseline Adjusted Mean Differences in Final

Disability (MODI) and Pain (NPRS) Between

the Different Groups and Subgroups

Abbreviations: CPR, patients with a negative status on the clinical prediction rule; CPR+, patients

with a positive status on the clinical prediction rule; LSE, patients treated with lumbar stabilization

exercises; MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index; MT, patients treated with manual therapy;

NPRS, numeric pain rating scale.

*Values are mean diference (95% condence interval).

Positive values indicate an advantage to LSE.

Positive values indicate an advantage to CPR+.

Positive values indicate an advantage to LSE CPR+.

Comparison MODI (0-100)* P Value NPRS (0-10)* P Value

LSE versus MT

5.0 (0.1, 9.9) .05 0.5 (0.3, 1.3) .26

CPR+ versus CPR

5.2 (0.2, 10.2) .04 0.1 (0.7, 0.9) .88

LSE CPR+ versus LSE CPR

8.7 (1.4, 15.9) .02 0.3 (0.9, 1.5) .67

LSE CPR+ versus MT CPR+

8.5 (0.7, 16.3) .03 0.7 (0.6, 1.9) .31

0

10

LSE CPR+ LSE CPR MT CPR+ MT CPR

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

S

u

c

c

e

s

s

R

a

t

e

,

%

FIGURE 3. Rate of success (%) among the 4

subgroups based on the original clinical prediction

rule and a cutof threshold of 50% decrease in

baseline modied Oswestry Disability Index score.

Abbreviations: LSE CPR, patients with a negative

status on the clinical prediction rule treated with

lumbar stabilization exercises; LSE CPR+, patients

with a positive status on the clinical prediction rule

treated with lumbar stabilization exercises; MT

CPR, patients with a negative status on the clinical

prediction rule treated with manual therapy; MT

CPR+, patients with a positive status on the clinical

prediction rule treated with manual therapy.

44-01 Rabin.indd 13 12/17/2013 5:18:42 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

14 | january 2014 | volume 44 | number 1 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

[ RESEARCH REPORT ]

Manual therapy seemed to be a suitable

comparison intervention because it is fre-

quently used in the management of LBP,

it is advocated by several clinical practice

guidelines,

1,19,76

and it has previously been

shown to have a varied level of success

when compared to LSE in heterogeneous

samples of patients with LBP.

11,24,50,62

Despite this rationale, recent evidence

suggests that spinal manipulation may

result in remediation of some muscle im-

pairments that are the focus of LSE pro-

grams, such as increased activation of the

transversus abdominis and lumbar mul-

tidi.

42,61

It is possible, therefore, that the

manipulation techniques included in the

MT intervention contributed to facilita-

tion of the deep spinal musculature and,

consequently, exerted an efect similar to

that attributed to LSE. Be that as it may,

when spinal manipulation has been pre-

viously performed specically on patients

who meet the stabilization CPR,

41

no ef-

fects were observed on the activation of

the transversus abdominis or internal

oblique, and the clinical efects (pain and

disability) did not exceed the minimal

clinically important threshold.

41

Further-

more, another study indicated that none

of the variables comprising the stabiliza-

tion CPR was associated with increased

activation of the lumbar multidus fol-

lowing spinal manipulation.

43

Finally,

any changes in activation of the lumbar

multidus that were observed immedi-

ately after manipulation did not seem to

be consistently sustained 3 to 4 days after

the application of the technique.

42

There-

fore, we do not believe the manipulation

techniques in our study were likely to

produce long-lasting or clinically signi-

cant changes in recruitment of the spinal

musculature of our patients.

During the process of CPR validation,

it is not unusual to attempt to modify

an original version of a CPR by adding,

omitting, or combining several of its

items.

67,68,81

Our ndings indicate that a

modied version of the CPR (mCPR),

containing only 2 of the original 4 items,

yielded a better predictive validity. The

mCPR did result in a signicant inter-

action efect with treatment, and the 2

corresponding pairwise comparisons

indicated a better outcome for patients

with a positive mCPR status treated with

TABLE 5

Baseline Adjusted Final Disability (MODI)

and Pain (NPRS) Among the Different Groups

and Subgroups Based on the mCPR*

Abbreviations: LSE, patients treated with lumbar stabilization exercises; mCPR, patients with a

negative status on the modied clinical prediction rule; mCPR+, patients with a positive status on the

modied clinical prediction rule; MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index; MT, patients treated

with manual therapy; NPRS, numeric pain rating scale.

*Values are mean (95% condence interval) and are provided based on intention-to-treat analysis.

Group MODI (0-100) NPRS (0-10)

LSE (n = 48) 15.4 (11.8, 18.9) 2.5 (1.9, 3.0)

MT (n = 57) 20.4 (17.2, 23.7) 3.0 (2.5, 3.5)

mCPR+ (n = 44) 16.5 (12.8, 20.3) 2.7 (2.1, 3.3)

mCPR (n = 61) 19.3 (16.1, 22.4) 2.8 (2.3, 3.3)

LSE mCPR+ (n = 20) 11.2 (5.7, 16.6) 2.0 (1.1, 2.9)

LSE mCPR (n = 28) 19.6 (15.0, 24.2) 2.9 (2.1, 3.6)

MT mCPR+ (n = 24) 21.9 (16.9, 26.9) 3.3 (2.5, 4.1)

MT mCPR (n = 33) 19.0 (14.7, 23.2) 2.8 (2.1, 3.4)

TABLE 6

Baseline Adjusted Mean Differences

in Final Disability (MODI) and Pain

(NPRS) Between the Different Groups

and Subgroups Based on the mCPR

Abbreviations: LSE, patients treated with lumbar stabilization exercises; mCPR, patients with a

negative status on the modied clinical prediction rule; mCPR+, patients with a positive status on the

modied clinical prediction rule; MODI, modied Oswestry Disability Index; MT, patients treated

with manual therapy; NPRS, numeric pain rating scale.

*Values are mean diference (95% condence interval) and are provided based on intention-to-treat

analysis.

Positive values indicate an advantage to LSE.

Positive values indicate an advantage to mCPR+.

Positive values indicate an advantage to LSE (mCPR+).

Comparison MODI (0-100)* P Value NPRS (0-10)* P Value

LSE versus MT

5.0 (0.2, 9.9) .04 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) .18

mCPR+ versus mCPR

2.7 (2.2, 7.7) .27 0.2 (0.6, 1.0) .67

LSE mCPR+ versus LSE mCPR

8.4 (1.3, 15.5) .02 0.8 (0.3, 2.0) .16

LSE mCPR+ versus MT mCPR+

10.7 (3.4, 18.1) .005 1.2 (0.0, 2.4) .05

0

10

LSE mCPR+ LSE mCPR MT mCPR+ MT mCPR

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

S

u

c

c

e

s

s

R

a

t

e

,

%

FIGURE 4. Rate of success (%) among the 4

subgroups based on the mCPR and a cutof

threshold of 50% decrease in baseline modied

Oswestry Disability Index score. Abbreviations:

LSE mCPR, patients with a negative status on the

modied clinical prediction rule treated with lumbar

stabilization exercises; LSE mCPR+, patients with

a positive status on the modied clinical prediction

rule treated with lumbar stabilization exercises;

mCPR, modied clinical prediction rule; MT mCPR,

patients with a negative status on the modied

clinical prediction rule treated with manual therapy;

MT mCPR+, patients with a positive status on the

modied clinical prediction rule treated with manual

therapy.

44-01 Rabin.indd 14 12/17/2013 5:18:43 PM

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

w

w

w

.

j

o

s

p

t

.

o

r

g

a

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

9

,

2

0

1

4

.

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

.

N

o

o

t

h

e

r

u

s

e

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

p

e

r

m

i

s

s

i

o

n

.

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

2

0

1

4

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

O

r

t

h

o

p

a

e

d

i

c

&

S

p

o

r

t

s

P

h

y

s

i

c

a

l

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 44 | number 1 | january 2014 | 15

LSE compared to patients treated with

unmatched interventions. Efect sizes

for these comparisons were either above

or slightly below the MCID of the MODI

(TABLE 6). These ndings seem to suggest

that the mCPR may be a more accurate

predictor of success following LSE.

It is acknowledged that because the

mCPR was derived retrospectively, its

efect on nal disability could have oc-

curred by chance alone. We believe, how-

ever, that several factors point against

this possibility. First, the mCPR is still

composed of items that have been previ-

ously linked to success following LSE in

the derivation study.

33

Second, no other

combination of items from the original

CPR produced similar ndings. Third,

we believe this 2-item version may even

possess a clearer biomechanical plau-

sibility compared to the original CPR.

The mCPR status is considered positive

when both aberrant lumbar movement

and a positive prone instability test are

present. Teyhen et al

70

demonstrated

that, compared to healthy individuals,

patients with LBP, aberrant movements,

and a positive prone instability test dem-

onstrate decreased control of lumbar

segmental mobility during midrange

lumbar motion.

This diference may rep-

resent an altered motor control strategy,

which suggests that an LSE program may

be most benecial under those circum-

stances. Furthermore, Hebert et al

31

dem-

onstrated that individuals with LBP and

a positive prone instability test displayed

decreased automatic activation of their

lumbar multidi compared to healthy

controls. Given the remediating efects

of LSE on muscle activation patterns,

73,74

it seems reasonable that LSE would be

most benecial for patients presenting

with such activation decits. In contrast,

it seems much less clear why patients

under the age of 40 would preferentially

benet from LSE as opposed to MT or

any other intervention. In fact, a younger

age has been previously associated with

a generally favorable prognosis following

an episode of LBP.

5,13,29,52,72

This nding

may help to explain why the CPR in its

original version seemed to be consistently

associated with a better outcome, regard-

less of the treatment received. Likewise,

it seems less intuitive why a greater SLR

range of motion would predict a better

outcome specically following LSE.

Finally, our entire sample included 40

patients with a positive CPR status ac-

cording to the original (4-item) version

and 44 patients with a positive mCPR

status. It could therefore be argued that

the slightly larger number of patients

with a positive mCPR might have simply

increased the power to detect an inter-

action with treatment group. However,

as only 31 patients had a positive status

according to both versions of the CPR, it

seems that the better predictive power of

the mCPR may not simply be a matter of

sample size but may be inherent in pa-

tients presenting with the 2 specic items

comprising the mCPR.

In summary, we believe that, in addi-

tion to its stronger statistical association

with success specically following LSE,

the mCPR carries a stronger biomechani-

cal plausibility as a predictor of success

following this intervention. Nevertheless,

due to its retrospective nature, an addi-

tional investigation is recommended to

prospectively establish the predictive va-

lidity of the mCPR.

Study Limitations

In addition to the aforementioned issues

of power and the retrospective nature of

some of the ndings, the current study

has several additional limitations. First,

the dropout rate was fairly high, in par-

ticular among the LSE group. Overall,

24 patients (22.8%) did not complete

the study. The dropout rate was greater

among patients receiving LSE (33%

versus 14%). We believe that the overall

dropout rate of the current study may

partly reect the dropout rate (31%)

among Israeli patients receiving outpa-

tient physical therapy for common mus-

culoskeletal conditions.

23

The greater

dropout rate among the LSE group also

suggests that patients receiving this in-

tervention may not have perceived it to

be as valuable as MT. The manual contact

included in the MT intervention could

have created an attention efect in favor

of this intervention, which, in turn, might

have contributed to better compliance.

Because this was suspected, the treating

clinicians were encouraged to provide

patients receiving LSE with continuous

verbal as well as manual cuing for main-

taining a neutral lumbar posture and an

ADIM. It seems, however, that this ap-

proach still failed to produce a similar

level of compliance among the 2 groups.