Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Endoscopic Forehead Lift. Technique and Case Presentations

Încărcat de

Nguyen DuongDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Endoscopic Forehead Lift. Technique and Case Presentations

Încărcat de

Nguyen DuongDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

J Oral Maxhfac Surg

54569.577, 1996

Endoscopic Forehead Lift: Technique

and Case Presentations

CLARK 0. TAYLOR, MD, DDS,* JAMES G. GREEN, MD, DDS,t

AND DAVID P. WISE, MD, DDS*

Purpose: The advent of the endoscopic forehead lift has provided an alterna-

tive to the conventional open approach. This article describes the basic tech-

nique, with some modifications, and reports three clinical cases.

Results: The subperiosteal forehead technique rejuvenates the upper third

of the face with no scalp resection, minimal risks of hypesthesia, limited risk

of alopecia, reduced tissue trauma, small camouflaged scars, less bleeding

and edema, improved postoperative comfort, and faster recovery compared

with the standard open techniques.

Conc/usions: The endoscopic subperiosteal forehead lift is a useful tech-

nique for providing rejuvenation of the upper third of the face. It reduces or

eliminates forehead rhytids by eliminating the reflex contracture of the frontalis

and contributes to softening of the vertical glabellar rhytids. Longitudinal stud-

ies will be required to assess the effectiveness of this technique compared

with open techniques.

The introduction of endoscopic surgical procedures

has provided an alternative to traditional approaches

for performing facial cosmetic surgery. The endo-

scopic technique allows controlled, precise surgery

through small incisions placed in inconspicuous loca-

tions. The development of endoscopic equipment de-

signed for esthetic surgery now permits rejuvenation

of the upper third of the face with no excision of hair-

bearing scalp, elimination or reduction of visible scar-

ring, and decreased risk of alopecia, anesthesia, or hyp-

esthesia. The basic techniques for the endoscopic

forehead lift, with some modifications and clinical

cases, are presented.

Indications and Preoperative Evaluation

The rationale for performing a forehead lift is to

reestablish the esthetic balance between the upper and

* Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center,

Director of Institute of Facial Surgery, Bismarck, ND.

t Senior Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Resident, Department of

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Nebraska Medical

Center, Omaha, NE.

$ Senior Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Resident, Department of

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Nebraska Medical

Center, Omaha, NE.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr Taylor: Insti-

tute of Facial Surgery, 416 N 6th St, Bismarck, ND 58501.

0 1996 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

0278-2391/96/5405-0006$3.00/O

middle thirds of the face that have been lost because of

the aging process. The position of the brow represents. a

key anatomic structure in rejuvenation of the upper

third of the face. Elimination or reduction of transverse

and vertical rhytids of the forehead and nasal region

represents the second important component of the fore-

head lift. Critical evaluation of postoperative results

shows that perhaps the most important effect of fore-

head rejuvenation is not the magnitude of brow eleva-

tion or the precision of brow position, but the elimina-

tion of the tense forehead. This is the result of

proper depressor muscle resection and forehead tissue

elevation and fixation.

The indications for a forehead lift are represented

by the anatomic changes of the aging upper face. These

include brow ptosis; lateral hooding; hypertrophic or

hyperactive corrugator, frontalis, and procerus mus-

cles, creating a tense forehead; disruption of the

smooth sweep of the brow into the nose; brow skin

descending over the orbit (pseudoblepharochalasis);

brow asymmetry; and reduction of the distance from

the upper eyelid tarsal crease to the eyebrow.] Some

of these changes may interfere with the patients vision

and necessitate surgical correction. Another common

indication for forehead rejuvenation is a history of pre-

vious cervicofacial rhytidectomy. Many patients who

undergo a facelift operation do not have a simultaneous

forehead lift performed. Postsurgical results often ac-

569

570 ENDOSCOPIC FOREHEAD LIFT

centuate the difference between the rejuvenated lower

two thirds and the untreated upper one third of the

face.

The aging upper face develops as gravity pulls the

forehead tissues down over the supraorbital rims and

eyelids, creating the appearance that the patient is tired,

angry, or sad. Decent of brow skin over the upper

eyelid can lead to inappropriate or excessive upper

blepharoplasty if normal brow position is not reestab-

lished first. The upper eyelid skinfold may extend be-

yond the lateral canthus onto the lateral periorbital

region (lateral hooding) and represents a hallmark of

brow ptosis. The forehead musculature becomes re-

flexively hyperactive in an effort to reposition the eye-

brows to a normal position. The constant counter-

action between the brow elevators (frontalis and

corrugator muscles) and the depressors (orbicularis,

procerus, corrugator, and depressor supercilii muscles)

leads to the development of characteristic transverse

and vertical rhytids and the classic clinically tense

forehead. The tense forehead may result in the brow

being held in the normal position at rest. The chronic

contraction of the forehead muscles is an often over-

looked cause of frontal headaches. Eventually, the ver-

tical distance between the brows and the hairline in-

creases, disrupting the balance between the upper and

middle thirds of the face. The distance between the

upper eyelid crease and eyebrow is also noted to de-

crease.lT4

Evaluation of the patient for a forehead lift requires

an understanding of the variations between female and

male esthetics. In women, the highest point of the

arched brow should be at the lateral limbus or canthus

of the eye. The relationship of the brow with the medial

orbital rim should create a smooth Y-shaped curvature.

The brow should be positioned slightly above the su-

praorbital rim, and the forehead should have few or

no horizontal or transverse rhytids. Men normally have

the brow positioned at the supraorbital rim, and the

brow creates a T-shaped configuration with the medial

orbital rim. The brow appears horizontal or mildly

arched, and variable amounts of vertical and horizontal

rhytids are acceptable. In both men and women, the

medial and lateral brow margins should be at the same

height to avoid a surprised, sad, tired, annoyed, or

angry appearance.5

Sex, age, skin quality, hair quantity and quality, hair

pattern, hairline, eyebrow position and shape, presence

of forehead, glabellar, and nasal rhytids, motor func-

tion of the forehead musculature, and bony architecture

must be systematically evaluated.6 Thorough evalua-

tion leads to identification of specific anatomic prob-

lems, selection of the proper surgical approach, and

improved treatment results. Although the literature

contains specific numbers for the diagnosis of brow

ptosis (less than 2.5 cm from the midpupil to the upper

edge of the brow), deficient brow-to-hairline measure-

ment (less than 5 cm from the top of the brow to

the hairline), and deficient upper eyelid crease-to-brow

distance (less than 1.5 cm), the patients input before

surgery and the surgeons assessment at the time of

surgery remain critical factors.* However, these mea-

surements can assist the surgeon in determining which

areas require treatment and which surgical approach

should be used.

The indications for an endoscopic forehead lift are

the same as those for the traditional approaches. The

best candidates are 30 to 50 years of age, with limited

skin excess, who show the early or classic signs of

brow ptosis. The endoscopic procedure is also suitable

for older individuals with excess skin but who are

unwilling to accept the undesirable sequelae of tradi-

tional open approaches. The endoscopic technique of-

fers the following advantages: no scalp resection, mini-

mal risk of hypesthesialanesthesia, limited risk of

alopecia, less tissue trauma, small camouflaged scars,

less bleeding and edema, improved postoperative com-

fort, and faster recovery.-

Endoscopic Technique

The patient is initially positioned in the semisupine

position, and intravenous sedation is induced. Before

beginning the forehead dissection, 2% lidocaine with

epinephrine 1: 100,000 is infiltrated in all proposed in-

cision marks and in the region of the supratrochlear

and supraorbital nerves. A small volume of anesthetic

solution (approximately 30 mL) is infiltrated in the

subgaleal plane to facilitate the dissection and for addi-

tional anesthesia. Further discussion regarding the tu-

mescent technique can be found in the article by

Schoen et al.

Three sagittal incisions, through periosteum to bone,

are initially made approximately 1 to 3 cm posterior

to the hairline. In addition, two horizontal incisions

down to the deep layer of the superficial temporalis

fascia are made in the temporal hair-bearing region of

the scalp over the temporalis muscle (Fig 1). The

proper layer is identified by manipulating both edges

of the surgical wound and observing the scalp tissues

sliding directly over the deep layer of the temporalis

fascia. The incisions are made approximately 1 to 1.5

cm in length to allow introduction of the endoscopic

telescope and instrumentation.

The pericranium is elevated with periosteal dis-

sectors using a blind technique, taking care to avoid

tearing the periosteal layer during elevation of the flap.

The entire forehead region is elevated down to ,a point

approximately 3 cm above the bony orbital rim. Poste-

riorly, the entire scalp is elevated blindly in a subperi-

osteal plane to the attachment of the occipitalis muscles

and laterally into the suprahelical areas. The endoscope

TAYLOR, GREEN, AND WISE

FIGURE 1. Artist rendition of the five incisions needed for the

endoscopic brow technique. Incisions 1 and 3 are parasagittal inci-

sions, incision 2 is a midsagittal incision, and incisions 4 and 5 are

temporal incisions (fifth incision is not shown).

is then inserted through one of the three sagittal access

ports to allow completion of the forehead dissection

under direct visualization in a color monitor (Fig 2).

The dissection is accomplished throughout the re-

maining extent of the forehead and in the area of the

supratrochlear and supraorbital neurovascular bundles

(See Fig 3 for overlying anatomy). Visualization is

optimized with saline irrigation, and suction is pro-

vided by a Frazier tip inserted into one of the open

sagittal incisions. Using soft tissue dissectors, the neu-

rovascular bundles are identified (Fig 4). Once the neu-

rovascular bundles are identified, the corrugator and

procerus muscles are directly visualized through the

endoscope, and they are either avulsed with a biting

instrument or their dermal attachments are transected

while taking care to avoid the neurovascular structures

in the area (Fig 5). Care is taken during this portion

of the procedure to avoid damage to the subcutaneous

or dermal tissues.

The temporal dissector is now inserted through the

temporal incision into the plane just superficial to the

deep layer of the superficial temporalis fascia. Under

direct visualization, the temporal dissector is used to

transect the temporalis fascial attachments along the

I3

FIGURE 2. A, Intraoperative view of endoscope and dissector in

place. B, Artist rendition of endoscope in the subperiosteal tissue

plane.

572 ENDOSCOPIC FOREHEAD LIFT

FIGURE 3. Artist rendition of the pertinent overlying anatomy in

the region where the endoscopic brow lift procedure is performed

(not shown are the corresponding arterial and venous counterparts

and the frontal branch of the facial nerve).

FIGURE 5. View through the endoscope showing the endoscopic

biting forceps resecting the corrugator supercilii muscle.

temporal crest and thus release the scalp flap from the

temporal crest region (Fig 6). Maintaining a proper

tissue plane is extremely important during this portion

of the procedure to avoid damage to the frontal branch

of the seventh cranial nerve. The temporalis fascial

attachments are released posteriorly until the entire

temporal and frontal flaps are mobile. Reference points

are marked on the bony skull at the anterior extent of

the coronal sagittal incisions and at the planned poste-

rior movement position using rotary air-driven instru-

mentation. The average posterior positioning in the

midsagittal region is 8 to 10 mm, whereas in the para-

sagittal region this movement is 10 to 12 mm. Using

skin hooks, the scalp is advanced posteriorly, and

screw holes are placed at the posterior reference mark.

Care is taken to recognize penetration through the outer

cortex to avoid perforation into the dural sinus or into

the brain. Luhr (Howmedia Inc, Rutherford, NJ) pan-

fixation screws are then inserted through the anterior

extent of the scalp flap into the prepared posterior hole

to anchor the scalp in a posterior position while simul-

taneously observing the brows for ideal orientation.

Traction is then placed in the temporal region to elimi-

nate any lateral hooding and to allow a smooth transi-

tion between the temporal and facial regions. This ad-

vancement in the temporal region is secured by

anchoring the anterior extent of the incision to the

temporalis fascia using a Maxon or .PDS (D & G

Monofil Inc, Manati, Puerto Rico) suture.

Should bleeding be encountered during any segment

of the procedure, it is easily controlled with electrocau-

tery. The sagittal and temporal incisions are then closed

with either staples or 4-O nylon sutures. A light pres-

sure dressing is placed for 48 hours. The patient is

given preoperative antibiotics and is maintained on

postoperative antibiotic therapy for 7 days. The cuta-

neous sutures are removed at 7 days, and the percutane-

ous cranial screws are removed at 12 to 14 days. After

the initial 48 hours, and for an additional 2 weeks after

FIGURE 4. View through the endoscope showing the supraorbital

neurovascular bundle and the endoscopic dissector.

FIGURE 6. View through the endoscope showing the temporal

dissector perforating through the junction of the temporalis fascial

attachments along the temporal crest region (lower right) to release

the scalp flap.

TAYLOR, GREEN, AND WISE

573

removal of screws, an elastic forehead dressing, such

as a tennis headband, is worn at night until full adher-

ence of the periosteum to the cranium is noted.

Report of Cases

Case 1

A 35-year-old white woman had features of an aging face,

including brow ptosis, herniated lower eyelid fat pads, and

lateral eyelid laxity, along with a indistinct mentocervical

angle (Fig 7). She underwent the following procedures: en-

doscopic forehead lift with corrugator resection, transcon-

junctival preexcision lower lid blepharoplasty, and sub-

mental liposuction. Her preoperative and postoperative

photographs demonstrate substantial improvement in her fa-

cial appearance. Note the significant decrease in the vertical

glabellar rhytids and lack of reflex contraction of the frontalis

muscle.

Case 2

A 67-year-old white woman presented 10 years after a direct

browlift with severe glabellar rhytids and medial brow ptosis

(Fig 8). She underwent an endoscopic forehead/brow rejuve-

nation technique with procerus and corrugator supercilii

muscle resection. Note the lack of significant forehead rhyt-

ids in the postoperative photographs, which were present

preoperatively.

Case 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with brow ptosis and corru-

gator hyperactivity (Fig 9). She underwent an endoscopic

forehead/brow rejuvenation technique with brow elevation

and corrugator resection.

Discussion

The endoscopic forehead technique is in its infancy,

and a number of different approaches and techniques

have been used with modifications being incorporated

on a trial-and-error basis. Incision design, tissue plane

approach, necessity for disruption of the frontalis mus-

cle, and tissue stabilization methods represent current

areas of controversy. With continued experience and

further research, the endoscopic approach will continue

to evolve and become more standardized.

The endoscopic forehead lift can be adequately per-

formed through the five incisions described. T-shaped,

chevron, and straight sagittal incision designs also have

been described. We favor the straight sagittal and para-

sagittal incisions over the T-shaped and chevron de-

signs because they can be closed with minimal diffi-

culty, are more esthetic, do not require scalp excision

with forehead repositioning, and carry a lower risk of

alopecia.

Although both subperiosteal and subgaleal ap-

proaches can be performed with the endoscopic tech-

nique, the subperiosteal plane has several advantages.

It is safe, quick, and can be done in a blind fashion

over a large percentage of the forehead. The lymphatic

and vascular channels are not disrupted, thereby pro-

ducing less edema and hemorrhage. Maintenance of

the lymphatics also permits early resolution of the sur-

gical edema. The subperiosteal approach allows for

creation of a nearly bloodless optical chamber, which

improves visualization of critical anatomic structures

(supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves, a small branch

of the superficial temporal artery associated with the

fat pad containing the frontal branches of the facial

nerve and the corrugator and procerus muscles). The

periosteum can also be elevated down to or slightly

beyond the supraorbital rim. Additionally, the perios-

teum is inelastic, and the released periosteum allows

effective traction for forehead and brow repositioning.

Readaptation to the cranium appears to be faster, giv-

ing earlier stability to the elevated tissues, and the

subperiosteal approach is less likely to suffer from

stress relaxation. The normal gliding mechanism of the

occipitalis-frontalis muscle is preserved, maintaining a

dynamic and stable brow position.

Access to the procerus and corrugator muscles is

excellent with either the subperiosteal or subgaleal ap-

proach. Resection can be accomplished easily after the

supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves have been iden-

tified and isolated. Partial or complete resection of

these muscles results in elimination or improvement

of the vertical glabellar and transverse nasal rhytids.

The muscle-dermis junction is easily identified, and

care should be used to avoid damage to the dermal

and cutaneous layers. External cutaneous depressions

have not been a problem, and fat grafts to replace the

resected muscle have not been necessary. Redraping

of the forehead tissue without depressor muscle resec-

tion is not advocated because the hyperactive muscle

activity is not eliminated and may reappear with adher-

ence of the periosteum to the cranium or the subgaleal

tissues to the pericranium.

Treatment of the frontalis muscle is controversial,

and some surgeons do not believe that sectioning or

scoring of the frontalis muscle is required or advisable.

The frontalis muscle is the primary elevator of the

brow, and diminishing its effect is not advantageous.

Proper brow and forehead repositioning appear to re-

duce frontalis hyperactivity and provide gradual im-

provement in the forehead rhytids and elimination of

the clinically tense forehead. In addition, elimina-

tion of the antagonistic effect of the forehead depressor

muscles further diminishes frontalis activity.

Posterior dissection of the parietal and occipital por-

tions of the scalp can be performed in either the subperi-

osteal or the subgaleal plane. Release in either plane

allows posterior sliding of the scalp and soft tissue

contracture. Hemorrhage, hypesthesia, and alopecia are

of minimal concern with either method.

HEAD LIFT

FIGURE 7. Case 1. Patient with an aging face showing brow ptosis, herniated lower eyelid fat pads and lateral eyelid laxity with an indistinct

mentocervical angle. A, Preoperative relaxed view. B, Preoperative frown. C, 6-month postoperative relaxed view. D, Postoperative frown.

TAYLOR, GREEN, AND WISE

FIGURE 8. Case 2. Sixty-seven-year-old woman who had a direct browlift performed approximately 10 years earlier. Note her recurrent

glabellar rhytids and medial brow ptosis. A, Preoperative relaxed view. B, Preoperative frown. C, h-month postoperative relaxed view. 0,

Postoperative frown.

576 ENDOSCOPIC FOREHEAD LIFT

FIGURE 9. Case 3. Patient with brow ptosis and corrugator hyperactivity. A, Preoperative relaxed view. B, Preoperative frown. C, 6-month

postoperative relaxed view. D, Postoperative frown.

TAYLOR, GREEN, AND WISE

Techniques for forehead and scalp fixation have

used sutures, miniscrews, or a combination of both.

Our technique precisely fixes the tissue directly to the

cranium with 1.7~mm diameter vitallium miniscrews

at the midsagittal and parasagittal incisions. Mini-

screws can be selected by length to match the level of

the scalp so as to reduce visibility and avoid interfer-

ence with daily hair hygiene. The concomitant use of

suspension sutures is eliminated, and the concern about

suture slippage or breakage is negated. The scalp tissue

does not react adversely to the vitallium miniscrews,

and removal can be accomplished without local anes-

thesia. When combined with the sagittal incisions,

scalp excision is not required, the risk of alopecia is

minimal, and wound closure is simple and esthetic.

The risk of entering the cranial vault or sagittal sinus

is minimal if the appropriate equipment and technique

are used. Suspension sutures are used to reposition the

lateral orbital and temporal tissues at the appropriate

level by attachment to the temporalis fascia.

The use of the endoscopic technique can be limited

by a number of predisposing factors. Significant

fronto-orbital bony irregularities that require extensive

recontouring and the need for excision of skin preclude

the use of the procedure. The presence of an exces-

sively high hairline (>6.0 to 6.5 cm from the brow)

also precludes any technique that will further lengthen

the forehead. The thick or tight skin and prominent

frontal and periorbital attachments in Asians, Ameri-

can Indians, and Latinos make elevation difficult, even

with open techniques. Other limiting factors include

the learning curve required to achieve optimal results,

use of new instrumentation, staff training, and the asso-

ciated overall investment.

Endoscopic and open forehead lift procedures are not

without possible complications and postoperative prob-

lems. However, certain postoperative problems may be

less frequent or totally avoidable with the endoscopic

technique. Anesthesia or hypesthesia associated with

coronal or trichophilic incisions are minimal or nonexis-

tent because the incisions are placed parallel to the sen-

577

sory nerves and dissection is subperiosteal. Alopecia is

also avoidable because there is minimal damage to hair

follicles, skin excision is not required, and there is less

tension on the scalp, reducing ischemia. Scarring is min-

imized because the incisions are hidden in the scalp,

small, and easily closed with simple techniques. Infec-

tion, hematoma, unsatisfactory contours, suboptimal

correction, skin slough, xerophthahnia, and cranial

nerve V (supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves) and

cranial nerve VII (frontal branch) injuries are possible

complications related not to a specific surgical approach,

but rather to improper operative technique and surgeon

error. Currently, no long-term studies exist to document

the potential for, and rate of, relapse of brow ptosis with

the endoscopic technique.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

Connell BF, Marten TJ: The male foreheadplasty: Recognizing

and treating aging in the upper face. Clin Plast Surg 18:653,

1991

McKinney P, Mossie RD, Zukowski ML: Criteria for the fore-

head lift. Aesthetic Plast Surg 15:141, 1991

Flowers RS, Caputy GG, Flowers SS: The biomechanics of

brow and frontalis function and its effect of blepharoplasty.

Clin Plast Surg 20:255, 1993

Wojtanoski MH: Bicoronal forehead lift. Aesthetic Plast Surg

l&33, 1994

Johnson CM Jr, Toriumi DM: Forehead deformities, in Krause

CJ, Mangat DS, Pasaorek N: Aesthetic Facial Surgery. Phila-

delphia, PA, Lippincott, 1991, pp 545-557

Connell BF, Lambros VS, Neurohr GH: The forehead lift: Tech-

niques to avoid complications and produce optimal results.

Aesthetic Plast Surg i3:217, 1989

Isse NG: Endoscooic facial reiuvenation: Endoforehead, the

functional lift. Case reports. Aesthetic Plast Surg 18:21, 1994

Ramirez OM: Endoscopic techniques in facial rejuvenation: An

overview. Part I. Aesthetic Plast Surg 8:141, 1994

Aiache AE: Endoscopic facelift. Aesthetic Plast Surg 18:275,

1994

Ramirez OM: Endoscopic full facelift. Aesthetic Plast Surg

l&363, 1994

Vasconez LO, Core GB, Gamboa-Bobadilla M, et al: Endo-

scopic techniques in coronal brow lifting. Plast Reconstr Surg

94:788, 1994

Chajchir A: Endoscopic subperiosteal forehead lift. Aesthetic

Plast Surg 18:269, 1994

Schoen SA, Taylor CO, Owsley TG: Tumescent technique in

cervicofacial rhytidectomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52:344,

1994

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Filler Placement and The Fat CompartmentsDocument14 paginiFiller Placement and The Fat CompartmentsNguyen Duong100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology-An Illustrated Colour TextDocument174 paginiObstetrics and Gynecology-An Illustrated Colour TextAlina CiubotariuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Aesthetic Facial ImplantsDocument21 paginiAesthetic Facial ImplantsNguyen DuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Traditional AbdominoplastyDocument23 paginiTraditional AbdominoplastyNguyen DuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Respiratory System of OxDocument14 paginiThe Respiratory System of OxHemant JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Prosthodontics CD - BookDocument7 paginiProsthodontics CD - BookFrances Bren MontealegreÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Chapter 06 Try inDocument18 paginiChapter 06 Try inمحمد حسنÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Audiometric TestingDocument12 paginiAudiometric TestingHeribertus AribawaÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Ijoi Vol 23-2Document100 paginiIjoi Vol 23-2Giovanni Eduardo Medina MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- MMT FaceDocument35 paginiMMT FaceRavneet singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Data Mentah Pasien CovidDocument280 paginiData Mentah Pasien CovidRizka Yuliana PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- ENT Exam Prep NotesDocument37 paginiENT Exam Prep NotesSimran KothariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Points in Making Complete Dentures Suction Effective and FunctionalDocument46 paginiPractical Points in Making Complete Dentures Suction Effective and FunctionalCostin SilviuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Sanna - CA Endo-Otoscopy - ABIDocument2 paginiSanna - CA Endo-Otoscopy - ABIcuba11Încă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Ent History Taking and Examination-1Document16 paginiEnt History Taking and Examination-1Jyotirmayee100% (5)

- Q2 - Week 1 - Day 4Document3 paginiQ2 - Week 1 - Day 4Erwin TusiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- 3 Development of FaceDocument25 pagini3 Development of FaceMohamad TallÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1091)

- Bald Thigh Syndrome of Greyhound Dogs - Gross and Microscopic FindingsDocument3 paginiBald Thigh Syndrome of Greyhound Dogs - Gross and Microscopic FindingsjenÎncă nu există evaluări

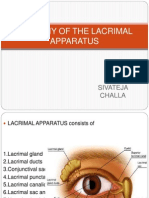

- Anatomy of The Lacrimal ApparatusDocument22 paginiAnatomy of The Lacrimal ApparatusSivateja Reddy ChallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nervous System Head InjuryDocument11 paginiNervous System Head InjurydimlyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orthodontics Part 8 Extractions in OrthodonticsDocument10 paginiOrthodontics Part 8 Extractions in OrthodonticsAdina SerbanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Anatomy of The HorseDocument410 paginiClinical Anatomy of The HorseKristina PriscanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Esthetics in Dental ImplantsDocument87 paginiEsthetics in Dental ImplantsRavi Uttara100% (3)

- Cricothyroidotomy 1Document42 paginiCricothyroidotomy 1Louis FortunatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- FaceDocument74 paginiFacehazell_aseronÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pola Penderita Rawat Inap THT-KL Di Blu Rsup Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Manado Periode Januari 2010 - Desember 2012Document8 paginiPola Penderita Rawat Inap THT-KL Di Blu Rsup Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Manado Periode Januari 2010 - Desember 2012micstainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Table Descending TractDocument3 paginiTable Descending TractirfanzukriÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Middle Superior Alveolar Nerve BlockDocument39 paginiMiddle Superior Alveolar Nerve Blockdaw022Încă nu există evaluări

- Perio GingivektomiDocument5 paginiPerio GingivektomiSafiraMaulidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dawson 1Document59 paginiDawson 1Hatem Ibrahim Ahmed AburiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Background: Congenital Hypothyroidism Pediatric HypothyroidismDocument1 paginăBackground: Congenital Hypothyroidism Pediatric HypothyroidismNiddy Rohim FebriadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- No BS Guide To Vision Improvement - Sept 2016Document18 paginiNo BS Guide To Vision Improvement - Sept 2016ShaiabbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trigemina Nerve Sem 2 WordDocument18 paginiTrigemina Nerve Sem 2 WordBharathi GudapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Special Senses NotesDocument17 paginiSpecial Senses NotesizabelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)