Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

What Is The Point of Being Good - Magda Ajtay-Horvath.

Încărcat de

Gábor Erik0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

23 vizualizări10 paginiMagda Ajtay-Horvath

The paper attempts to present the controversially received novel by the contemporary British author of

Hungarian origin Tibor Fischer. Good to be God is the story of a jobless loser who finally tries his luck as a

spiritual leader in “God business” in Miami. The adventures told by the protagonist have generic meaning

suggesting the emptiness and aimlessness of modern times where the stability of the traditional values is

entirely missing. The stories do not lead the readers towards any conclusion, the novel is not finished, just

given up. However, the stories are capable of showing a world in which each of us recognizes oneself, and thus

does not judge hard on the attitudes, rather smiles and accepts them in a liberal way. The effect of the plotless

story lies in the author’s satirical view upon modern life told in a stand-up-comedy-like style. This

“observational comedy” reveals the author’s acute observation of the controversies of life which are often

rendered in maxims and linguistic subtleties that can be a real challenge for the Hungarian translator as well.

Key words: postmodern novel, observational comedy, satire, maxims and linguistic jokes

Titlu original

What is the Point of Being Good - Magda Ajtay-Horvath.

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentMagda Ajtay-Horvath

The paper attempts to present the controversially received novel by the contemporary British author of

Hungarian origin Tibor Fischer. Good to be God is the story of a jobless loser who finally tries his luck as a

spiritual leader in “God business” in Miami. The adventures told by the protagonist have generic meaning

suggesting the emptiness and aimlessness of modern times where the stability of the traditional values is

entirely missing. The stories do not lead the readers towards any conclusion, the novel is not finished, just

given up. However, the stories are capable of showing a world in which each of us recognizes oneself, and thus

does not judge hard on the attitudes, rather smiles and accepts them in a liberal way. The effect of the plotless

story lies in the author’s satirical view upon modern life told in a stand-up-comedy-like style. This

“observational comedy” reveals the author’s acute observation of the controversies of life which are often

rendered in maxims and linguistic subtleties that can be a real challenge for the Hungarian translator as well.

Key words: postmodern novel, observational comedy, satire, maxims and linguistic jokes

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

23 vizualizări10 paginiWhat Is The Point of Being Good - Magda Ajtay-Horvath.

Încărcat de

Gábor ErikMagda Ajtay-Horvath

The paper attempts to present the controversially received novel by the contemporary British author of

Hungarian origin Tibor Fischer. Good to be God is the story of a jobless loser who finally tries his luck as a

spiritual leader in “God business” in Miami. The adventures told by the protagonist have generic meaning

suggesting the emptiness and aimlessness of modern times where the stability of the traditional values is

entirely missing. The stories do not lead the readers towards any conclusion, the novel is not finished, just

given up. However, the stories are capable of showing a world in which each of us recognizes oneself, and thus

does not judge hard on the attitudes, rather smiles and accepts them in a liberal way. The effect of the plotless

story lies in the author’s satirical view upon modern life told in a stand-up-comedy-like style. This

“observational comedy” reveals the author’s acute observation of the controversies of life which are often

rendered in maxims and linguistic subtleties that can be a real challenge for the Hungarian translator as well.

Key words: postmodern novel, observational comedy, satire, maxims and linguistic jokes

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 10

1

Whats the point of being good?

(The source of fun and wisdom in Tibor Fischers Good to be God)

Magda Ajtay-Horvth

*

University College of Nyregyhza

Abstract:

The paper attempts to present the controversially received novel by the contemporary British author of

Hungarian origin Tibor Fischer. Good to be God is the story of a jobless loser who finally tries his luck as a

spiritual leader in God business in Miami. The adventures told by the protagonist have generic meaning

suggesting the emptiness and aimlessness of modern times where the stability of the traditional values is

entirely missing. The stories do not lead the readers towards any conclusion, the novel is not finished, just

given up. However, the stories are capable of showing a world in which each of us recognizes oneself, and thus

does not judge hard on the attitudes, rather smiles and accepts them in a liberal way. The effect of the plotless

story lies in the authors satirical view upon modern life told in a stand-up-comedy-like style. This

observational comedy reveals the authors acute observation of the controversies of life which are often

rendered in maxims and linguistic subtleties that can be a real challenge for the Hungarian translator as well.

Key words: postmodern novel, observational comedy, satire, maxims and linguistic jokes

Tibor Fischers novel published in 2008 is a symptomatic modern text presenting samples of

plights of the European and North American average citizen, so much disappointed by the

human conditions of contemporary civilization and still glad for living in it and capable of

enjoying it.

The novel has several shortcomings, or rather, intentionally does not satisfy the

expectations raised by a traditional novel. In other words, Good to be God is a postmodern

novel consisting of a number of incidents told in the first person in a style very similar to the

trendy stand-up comedies of today. It lacks a traditional plot, however it has a clear

beginning and a catchy title, which, similar to a good play, can arouse the readers

expectations. Nonetheless, the novel itself fails to satisfy these expectations, that is, it does

*

Ajtay-Horvth Magda is Head of the Department of English Language and Literature at the College of

Nyregyhza, Hungary. She graduated from the Babe-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca in 1984 and received her

PhD in Linguistics from the same university in 1997. Her area of research covers Comparative stylistics, Stylistics

of Translation, and Literary Studies. She published two books (A szecesszi stlusjegyei az angol s a magyar

irodalomban 2001; Szvegek, nyelvek, kultrk (2010) and edited Endeavours: Occasional Papers on Linguistics

Literature, Civilization and Methodology (Nyregyhza: Bessenyei Kiad. 221 lap, lektorlt). Email address:

ajtayhm@nyf.hu

2

not reach any solution, be it a relief or a failure. It never turns out what it is like to be God,

because Tyndale Corbett, though he goes into the religion business and becomes a casual

leader of a community, is far from being God-like. The title anticipates some sort of

revelation which the protagonist never achieves. The pettiness and triviality of the incidents

suggest that the postmodern age we live in is incapable to provoke any majestic experience,

or the individuals fail to perceive the world as a stage where major events can take place.

And still, Fischer is able to turn this triviality into a textual material, into a stretch of language

worth reading, this being perhaps both the greatest contradiction and the greatest point of

the book.

The hopeless view upon life is articulated in cynicism, proving that the protagonist

knows the depths and widths of life. The problem with cynicism is similar to the feeling

characterizing the general impression induced by the entire novel: The one problem with

turning cynical and dishonest is that you can never succeed completely(Fischer 70).

The beginning of the novel is similar to the first scene of a drama: in nine lines it

creates the desperate mood of the jobless, loser protagonist whose money, marriage, home

and health are all gone, along with his job. Tyndale, who strived in vain in life to earn an

honest living, finally at around forty loses his job, which results in self-pity and loss of self-

esteem. The short section quoted below ends in an important remark referring to the

honesty of the protagonist. The forthcoming paragraph subtly evokes implied meanings:

You know when youre in trouble. You know youre in trouble when you phone and no one

phones back. You know youre in trouble when you get back home, the doors been kicked in,

the only thing stolen is the lock (its the only thing worth stealing), and your burglar has left a

note urging you to pull yourself together.

This isnt funny when it happens to you.

I tried to live my life decently. For a long time. I really did, but it did not work

(Fischer 3).

Contemplating about joblessness is a recurrent topic of the novel, at which point the

author as a first person narrator again proves to be sensitively knowledgeable of the plight:

If one is a failure machine, it is wonderful to be mistaken for someone; thats one of the

3

worst things about unemployment the conclusion youre nothing. Probably in the great

scheme of things we all are, but you dont want to feel it (Fischer 35).

Bitterness from past experiences is interwoven with the present course of

happenings suggesting that misery and disgrace are perpetual, handed down from one

generation to the next. The protagonist remarks at a point: I think about how I paid taxes all

my life, how my parents did too. Then when my mother was ill, how nothing happened at

the hospital. You pay tax, and you get nothing. No, thats not true, you get shit (Fischer 41).

This hopeless situation seems to change, due partly to an unexpected meeting with

an old schoolmate, who, having grown tired of his remunerative, however boring work,

sends Tyndale on a business trip to Miami instead of himself, endowing him with his own

passport and credit card. Both Tyndale and Nelson are typical 21

st

century characters, middle

aged men, with less hair and more stinginess. Tyndale jobless, Nelson burnt out, with a

dire job, constantly worrying for the future, with huge mortgage, kids for whose education

he has to save up.

Arriving in Miami, Tyndale feels new, heavy and holy, experiences a surge of self

and enters into the religion business taking over a small congregation from its pastor

Hierophant, a Vietnam veteran who can lead an easy life in Miami owing to his military

pension. The paradox of the situation in itself is very characteristic of the controversies of

the alienated and at the same time credulous society, which accepts a jobless lighting

salesman as a spiritual leader and psychological advisor: Act natural the protagonist is

advised, and then he wonders what exactly this would means in his case: Act like an

unemployed lighting salesman? Act like an unemployed lighting salesman acting like hes

God? (Fischer 71). It is not clear how the church which he temporarily takes over and which

is advertised as affordable paradise (Fischer 73) differs from the mainstream churches, and

this is not anyones business as long as it functions and tells the people what they want to

hear.

The reason why the reader does not quit reading this novel definitely lies in its style.

Small remarks often provoke an enjoyable smile or the astonishing feeling of yes, I myself

have experienced exactly the same. The author proves to be an acute observer of everyday

happenings and is able to draw commonsense conclusions from them, always with some

freshness. This is revealed by the casual remarks of the protagonist, which are always

sharply contrasted with their general validity of their meaning.

4

Humour

Fischers humour has several sources. It often arises from the unusual activities, jobs or

habits that the characters pursue, do or possess.

Nelson, Tyndales friend, for example, works as a representative for a company that

manufactures handcuffs. Another woman character, who randomly shows up, has a business

of selling toe-separators.

Euphemisms instead of naming the proper activity also constitute the source of

humour: pole dancing clubs are called bird-watching, visiting brothels is referred to as

pipe-cleaning.

Conciseness

A method used by Fischer is to give a rather lengthy and detailed description of a situation or

happening full with particulars, then he suddenly comes to a halt by formulating a general

and very concise conclusion. Tyndale, for example, accepts Nelsons suggestion with the

following remark:

If hed offered me a week cleaning his toilet, Id have accepted. Doing anything is better

than doing nothing (Fischer 9).

Having arrived in Miami Tyndale remarks:

Not caring about your problem is as good as not having them(Fischer 12).

Examples for aphoristic conclusions also often occur:

Being right doesnt do you too much good. Being right doesnt improve the quality of your

life, any more than wearing yellow socks (Fischer 22); or Suicide panders to our laziness.

And laziness, laziness always wins. Sooner or later. Thats the only law(Fischer 19); the

characters who go on about caring for others are nearly always the most selfish (Fischer 9).

Something doesnt work for you doesnt mean its not working somewhere else (Fischer

80).

There is a conspiracy. Its called the world (Fischer 82).

5

I arrived here with no baggage, nothing to help me or hinder me (Fischer 83).

We must notice the alliteration that exercises a centripetal force that keeps the two words

tightly together, however the contradictory meanings produce a counterforce pushing the

words apart. Concentrated wisdom can be noticed in the following maxims:

Action is only speeded-up waiting (Fischer 139).

Laziness always wins (Fischer 191).

Naturally, the only thing worse than sinning, is sinning ridiculously( Fischer 177).

Bitterness balanced by optimism

Pessimism and bitterness are often balanced by a note of optimism, just like in life,

downs are followed by ups, pessimistic periods by promising ones.

The chapter relating the heros departure from Great Britain to Miami starts with the

following remark:

There are places that are waiting for you. You may not have learnt this, but there are

(Fischer 10).

Talking about the strong business competition the protagonist used to experience

with the carefully conceived and narrow niches which barely let one live, the protagonist

states:

Everything was carefully calculated, products priced to be just affordable by the clients,

products with just enough commission to make them worth selling. The cheese was no

bigger than required by the trap(Fischer 28).

The preliminary standpoint of the first person narrator is his own plight, namely the

status of a jobless man who knows from experience that, Its easy to talk about

benevolence when the sun is shining and bank accounts are full, not so easy when the

tortures are going on (Fischer 70). Your moral bank account is a currency that cant buy

you anything (Fischer 84). This maxim again contradicts the experiential meaning regarding

6

money and bank account with which anything can be bought. It is expected that moral bank

account should have a similar role, but experience shows quite the contrary.

The media ruled and manipulated world is bitterly mocked at in the following

remarks:

Never believe anything you read in the papers (Fischer 89). Its strange how when youre

getting what you want, you still try to ruin it (Fischer 92), Why is it you always get what

you want in a way you dont want it (Fischer 92). All application forms are designed to

humiliate and subordinate the applicant (Fischer 102),

hinting at the modern practise of surveying everybody on the most various matters.

Redundant, long, senseless and irresponsible talk in modern life is ridiculed in the

following remark:

I dont know why we all have this urge to talk confidently about subjects we have no

knowledge of (Fischer 120). Or, another talkative character mastered some technique of

breathing while simultaneously talking (Fischer 136).

About the futility of buying lottery tickets as a last hope for those who are hopeless

the author concludes:

You can work hard to buy lots of tickets, you can buy lots of tickets if you put your mind to

it. You can buy lots of tickets and win nothing (Fischer 128).

Experience gathered on group travelings is compressed in the following section:

It is noticeable that whenever you travel the stupid and ignorant are always the loudest.

They cant talk, they have to shout, and are always to be found on public transport (Fischer

2008:129).

Bitterness is finely balanced by optimism in the following sentences:

And if bad luck doesnt upset you, its not really such bad luck ( Fischer 138).

7

I hate beggars as much as bankers and lawyers, for the same reason they take advantage

of others (Fischer 158).

Anger, like most emotions, is a waste of time (Fischer 202).

Getting concerned about the problems of your fellow man is one way of fleeing your own

(Fischer 203).

I dont understand myself, so its no surprise I cant understand others (Fischer 219).

The uselessness of being good, or perhaps being God, is recurrently expressed in the

novel:

there is no benefit in living sensibly (Fischer 209); goodness and decency should be

punished (Fischer 211); shes a very decent soul and thats why shell always run a small

shop (Fischer 214); compassion is a disease, compassion may also be another form of

arrogance (Fischer 220-221); dont expect any reward (Fischer 237); the most important

skill you have to have in life, working with people you hate (Fischer 254); miracles occur

when you get exactly what you want usually without you knowing what you want (Fischer

47); power is the drug that destroys the strong (Fischer 53).

Fischer often arrives at far-reaching philosophical depths when he or rather one of

his characters defines human life and the refinement of civilization as a constant process of

hiding something:

Our earthly time is mostly a battle to conceal. To conceal our odours, our disappointing

features. Theres the physical and then theres the spiritual striving to hide the greed, the

hate, the weakness. Civilisation is spiritual clothing. Its a pretence that we are better than

we are, spiritual garb, spiritual aftershave (Fischer 197).

The quoted fragment clearly demonstrates the freshness of Fischers style. Stylistically the

light-handed metaphors subtly express the parallel between life, which is similar to a battle

emphasised later in the text by the synonym strive. The aim of this battle is to hide, again

reiterated by the synonym to conceal. This association may seem strange enough because

battles are carried out for very material reasons, strivings also achieve something definable,

however, generally not of a material sort. In this context the activity (battle, strive) is carried

8

out in order to achieve the invisibility of something, namely, the invisibility of negative

human features: greediness, hatred and other human weaknesses. After these rather

detailed sentences a maxim follows as a conclusion: Civilisation is spiritual clothing which

again swings the readers associations from the very abstract (civilisation, spiritual) to the

very concrete: clothing, whose meaning is again reiterated by the noun garb later on. In

the subsequent sentence, however, the author devaluates the meaning of the activity

(battle, strive) by stating that this is nothing more than a pretence, a way of cheating

ourselves to look better than what we really are or at least to make other people see us

better than what we really are. Life being identified with spiritual garb is again a striking

association. The semantic domain of the noun garb is very far from the domain of the

adjective spiritual preceding it and even much further from the noun aftershave,

denoting a far more elusive entity than the materialistic garb.

Linguistic jokes

When appreciating the linguistic achievements of the novel, linguistic jokes should be

devoted proper attention in Tibor Fischers text. The title itself is the first example: good to

be god besides its alliterating words is almost homophonic with good to be good, which

is often counterpoised by the conclusions the protagonist draws, namely, there is no point in

being good, in other words, there is no point in being god. Hence the meaning of God clearly

becomes the synonym of good in the given context of the novel in accordance with the

convention of the Christian system of belief.

Synonymy and words with multiple meanings are often exploited by the author. At a

meeting with scarce attendance there are a couple of couples who look like concern is their

major concern (Fischer 21).

Puns

Homophones function as a rich source of humour and playfulness, thus proving the authors

mastery of language. Talking about someone who likes sitting in the church, Fischer remarks

that the person is wholly holy (Fischer 76);

youve proved to be a slowie rather than a showie (Ficher118);

9

God wants winners not sinners (Fischer 140).

Talking about the relationship between the pastor and his congregation, Fischer

concludes in a rhyming sentence: your flock expects you to talk a lot (Fischer 65). When

mentioning the freedom of the individual to choose the rite of a religion the author remarks

Right rite. Rite right (Fischer 69). This figure of speech called chiasmus repeats the

words in a reverse order in the two subsequent sentences, emphasising that both meanings

are equally correct and acceptable.

Contradicting old sayings, refreshing old thinking

Contradicting old sayings serves a double function: on the one hand, it is an effective way of

refreshing the worn out linguistic stock and the traditional way of thinking standing behind

it, on the other hand, it proves the authors fresh look upon old clichs. Thus linguistic

innovation reveals intelligent thinking. Talking about a past failure, where the business

partner was fond of drinking, the author, paraphrasing the saying: a small leak will destroy

a great ship formulates the following conclusion:

Holliss drinking didnt destroy the club, but then a small hole in a keel doesnt destroy the

yacht either, its the ocean that does the job. In our case, the banks (Fischer 25).

Friends in need impede, (Fischer 195) again, contradicts the saying Friends in need are

friends indeed.

Linguistic device to intensify meaning

Adverbs derived from the same adjectives, besides alliterating, contribute to the intensified

effect of the meaning. In rhetoric this redundant figure of speech bears the name of figura

etymologica, which involves the repetition of cognate words in relatively close proximity to

each other. In the following example, the adverb and the adjective brought into close

syntactic connection share the same etymology: insanely insane (Fischer 141), or

tragically tragic in the following redundant sentence: This is a tragically tragic case of

tragic misunderstanding tragically (Fischer 143).

10

Applying different forms of a similar root varied by the use of a privative prefix in

case of one of the elements involved also augments the effect of the phrase as in the

examples below: to unknot the unknottable knot (Fischer 147), dead undeaded (Fischer

160), surviving the unsurvivable (Fisher 160).

Gradation, as a means of intensifying meaning, is achieved by individual linguistic

invention as in the example marbiler marble (Fischer 166).

Naming

Fischer chooses rather unusual names for his characters. The pastor, from whom the

protagonist takes over the congregation, is called Hierophant, a name with an undeniable

Greek echo. Tyndales helper is called Dishonest Dave, other two are Gamay and Muscat, the

congregation is called the Fixico Sisters run by criminals who are finally charged with twelve

murders.

The self-made pastor is identified by several synonyms in the text: he is a spiritual

pharmacist (Fischer 147), God dealer (Fischer 156), an arsehole who saved the world

(Fischer 193), a person who is running a Church, someone who says something for

ecclesiastical emergencies, a cult master (Fischer 45), or a person going into God business.

The two congregations often competing with each other are called Church of Heavily

Armed Christ and The Temple of Extreme Abundance.

Conclusion: Walk on and laugh. Thats the way

This is the recommendation of one of the characters to another one, and perhaps this might

characterize the readers attitude as well, who, having read the novel, is partly bitter for not

having found a traditional definite message in the novel, partly ironic because s/he is

compelled to realize that the novel, as it is, is very much like our superficial shallow life.

Finally, however, s/he is consoled by the tolerant wisdom which arises from the book and its

linguistic achievements and, last but not least, by its underlying infectious optimism. Walk

on and laugh. Thats the way.

Works Cited

Fischer, Tibor. Good to be God. Richmond: Alma Books Ltd., 2008.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Translation of a Translation: Analyzing Tibor Fischer’s Novel Under the Frog in its Original English and Hungarian Translated VersionsDocument9 paginiThe Translation of a Translation: Analyzing Tibor Fischer’s Novel Under the Frog in its Original English and Hungarian Translated VersionsbuffettoscaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arjen de Korte Literature and Language Learning PDFDocument5 paginiArjen de Korte Literature and Language Learning PDFdexcrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hungarians and The Canadian Theatre The Case of Peter HayDocument8 paginiHungarians and The Canadian Theatre The Case of Peter HayGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Carpathian Basin in The 13. CenturyDocument1 paginăThe Carpathian Basin in The 13. CenturyGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Borrowing of Place Names in The Uralian LanguagesDocument223 paginiBorrowing of Place Names in The Uralian LanguagesGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some Observations On Hungarian-American Ties and Contacts - Zsolt VirágosDocument9 paginiSome Observations On Hungarian-American Ties and Contacts - Zsolt VirágosGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- From The Noon Bell To The Lads of PestDocument58 paginiFrom The Noon Bell To The Lads of PestGábor Erik100% (1)

- The Carpathian Basin Before The Hungarian Conquest in The 9th CenturyDocument1 paginăThe Carpathian Basin Before The Hungarian Conquest in The 9th CenturyGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Climate Change and Local GovernanceDocument274 paginiClimate Change and Local GovernanceGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blue Paper 2007Document30 paginiBlue Paper 2007Gábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Austro Hungarian EmpireDocument8 paginiAustro Hungarian EmpireGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bibliography Ethnic Conflict and Ethnic Conflict ManagementDocument47 paginiBibliography Ethnic Conflict and Ethnic Conflict ManagementGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 1956 Hungarian Revolution and The Soviet Bloc Countries: Reactions and RepercussionsDocument154 paginiThe 1956 Hungarian Revolution and The Soviet Bloc Countries: Reactions and RepercussionsGábor Erik100% (1)

- Austria-Hungary and The WarDocument65 paginiAustria-Hungary and The WarGábor Erik100% (1)

- Austria-Hungary in 1914Document1 paginăAustria-Hungary in 1914Gábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kossuth in New EnglandDocument366 paginiKossuth in New EnglandGábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

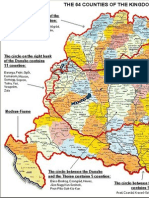

- The 64 Counties of Thekingdom of Hungary in 1876Document1 paginăThe 64 Counties of Thekingdom of Hungary in 1876Gábor ErikÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Folk Tales of MagyarsDocument518 paginiThe Folk Tales of MagyarsGábor Erik100% (6)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Im 412 - Human Behavior in Organization: University of Southern Mindanao Kidapawan City Campus Sudapin, Kidapawan CityDocument15 paginiIm 412 - Human Behavior in Organization: University of Southern Mindanao Kidapawan City Campus Sudapin, Kidapawan CityApril Joy Necor PorceloÎncă nu există evaluări

- DeputationDocument10 paginiDeputationRohish Mehta67% (3)

- Introduccion A La Filosofia HermeneuticaDocument3 paginiIntroduccion A La Filosofia HermeneuticaCamilo Andres Reina GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy of BusinessDocument9 paginiPhilosophy of BusinessIguodala OwieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surprise in ChessDocument116 paginiSurprise in Chesscrisstian01100% (1)

- A Universal Instability of Many-Dimensional Oscillator SystemsDocument117 paginiA Universal Instability of Many-Dimensional Oscillator SystemsBrishen Hawkins100% (1)

- Vedic Chart PDF - AspDocument18 paginiVedic Chart PDF - Aspbhavin.b.kothari2708Încă nu există evaluări

- VU21444 - Identify Australian Leisure ActivitiesDocument9 paginiVU21444 - Identify Australian Leisure ActivitiesjikoljiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design and Analysis of Indexing Type of Drill JigDocument6 paginiDesign and Analysis of Indexing Type of Drill JigInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Încă nu există evaluări

- Quantifying Technology Leadership in LTE Standard DevelopmentDocument35 paginiQuantifying Technology Leadership in LTE Standard Developmenttech_geekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gava VisualizationDocument41 paginiGava VisualizationDani FtwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Análisis Semiótico de Los Carteles de La Pélicula The HelpDocument5 paginiAnálisis Semiótico de Los Carteles de La Pélicula The HelpSara IsazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lyotard & Postmodernism (Theories & Methodologies Essay 2)Document12 paginiLyotard & Postmodernism (Theories & Methodologies Essay 2)David Jones100% (1)

- A New Map of CensorshipDocument8 paginiA New Map of CensorshipThe DreamerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Garate Curriculum Viate 2013Document11 paginiGarate Curriculum Viate 2013api-211764890Încă nu există evaluări

- Sonship Edification IntroductionDocument12 paginiSonship Edification Introductionsommy55Încă nu există evaluări

- Implementasi Nilai-Nilai Karakter Buddhis Pada Sekolah Minggu Buddha Mandala Maitreya PekanbaruDocument14 paginiImplementasi Nilai-Nilai Karakter Buddhis Pada Sekolah Minggu Buddha Mandala Maitreya PekanbaruJordy SteffanusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide To Writing Economics Term PapersDocument6 paginiGuide To Writing Economics Term PapersMradul YadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Densetsu No Yuusha No Densetsu Vol 8Document146 paginiDensetsu No Yuusha No Densetsu Vol 8brackmadarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Court upholds dismissal of graft case against Carmona officialsDocument15 paginiCourt upholds dismissal of graft case against Carmona officialsMary May AbellonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Lesson - CircuitsDocument9 paginiScience Lesson - Circuitsapi-280467536Încă nu există evaluări

- Shri Ram Hanuman ChalisaDocument12 paginiShri Ram Hanuman ChalisaRaman KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benefits of empathy in educationDocument2 paginiBenefits of empathy in educationJenica BunyiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intercultural Differences in Global Workplace CommunicationDocument48 paginiIntercultural Differences in Global Workplace CommunicationAlmabnoudi SabriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inductive Approach Is Advocated by Pestalaozzi and Francis BaconDocument9 paginiInductive Approach Is Advocated by Pestalaozzi and Francis BaconSalma JanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corporate Environmental Management SYSTEMS AND STRATEGIESDocument15 paginiCorporate Environmental Management SYSTEMS AND STRATEGIESGaurav ShastriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idioms, Sentence CorrectionDocument24 paginiIdioms, Sentence CorrectionJahanzaib KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 12Document7 paginiChapter 12Jannibee EstreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power Evangelism Manual: John 4:35, "Say Not Ye, There Are Yet Four Months, and Then ComethDocument65 paginiPower Evangelism Manual: John 4:35, "Say Not Ye, There Are Yet Four Months, and Then Comethdomierh88Încă nu există evaluări