Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Friedrich Krotz

Încărcat de

Miguel Sá0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

43 vizualizări16 paginiDrepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

43 vizualizări16 paginiFriedrich Krotz

Încărcat de

Miguel SáDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 16

THE RESEARCHING AND TEACHING COMMUNICATION SERIES

CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN

MEDIASPHERE

THE INTELLECTUAL WORK OF THE 2011 ECREA EUROPEAN

MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION DOCTORAL SUMMER SCHOOL

THE RESEARCHING AND TEACHING COMMUNICATION SERIES

Ljubljana, 2011

CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE.

The Intellectual Work of the 2011 ECREA European Media and Communication Doctoral Summer

School.

Edited by: Ilija Tomanic Trivundza, Nico Carpentier, Hannu Nieminen, Pille Pruulmann-VenerIeldt,

Richard Kilborn, Ebba Sundin and Tobias Olsson.

Series: The Researching And Teaching Communication Series

Series editors: Nico Carpentier and Pille Pruulmann-VenerIeldt

Published by: Faculty oI Social Sciences: Zalozba FDV

For publisher: Hermina Krajnc

Copyright Authors 2011

All rights reserved.

Reviewer: Mojca Pajnik

Book cover: Ilija Tomanic Trivundza

Design and layout: Vasja Lebaric

Language editing: Kyrill Dissanayake

Photographs: Ilija Tomanic Trivundza, Franois Heinderyckx, Andrea Davide Cuman, and JeoIIrey

Gaspard.

Printed by: Tiskarna Radovljica

Print run: 400 copies

Electronic version accessible at: http://www.researchingcommunication.eu

The 2011 European Media and Communication Doctoral Summer School (Ljubljana, August

14-27) was supported by the LiIelong Learning Programme Erasmus Intensive Programme project

(grant agreement reIerence number: 2010-7242), the University oI Ljubljana the Department oI

Media and Communication Studies and the Faculty oI Social Sciences, a consortium oI 22 universi-

ties, and the Slovene Communication Association. AIfliated partners oI the programme were the

European Communication Research and Education Association (ECREA), the Finnish National

Research School, and COST Action IS0906 TransIorming Audiences, TransIorming Societies.

The publishing oI this book was supported by the Slovene Communication Association and the

European Communication Research and Education Association (ECREA).

ClP - Katalozni zapis o publikaoiji

Narodna in univerzitetna knjiznioa, Ljubljana

316.77(082)

LCRLA Luropean Media and Communioation Uootoral 3ummer 3ohool (2011

, Ljubljana)

Critioal perspeotives on the Luropean mediasphere [Llektronski

vir] : the intelleotual work of the 2011 LCRLA Luropean Media and

Communioation Uootoral 3ummer 3ohool, [Ljubljana, 14 - 27 August] /

[edited by llija 1omanio 1rivundza ... [et al.] , photoghraphs

llija 1omanio 1rivundza ... et al.]. - Ll. knjiga. - Ljubljana :

laoulty of 3ooial 3oienoes, 2011. - (1he researohing and teaohing

oommunioation series (0nline), l33N 1736-4752)

Naoin dostopa (uRL): http://www.researohingoommunioation.eu

l3BN 978-961-235-583-8 (pdf)

1. 0l. stv. nasl. 2. 1omanio 1rivundza, llija, 1974-

260946432

http://www.Idv.uni-lj.si/zalozba/

Media as a societal structure and a

situational frame for communicative

aclion: A dehnilion of concepls

1

Friedrich Krotz

1. INTRODUCTION

We live in a historical phase of ongoing, ever-accelerating development.

CIolaIisalion, individuaIisalion, conneiciaIisalion, nedializalion and

olhei concepls aie used lo desciile specihc aspecls of lhis deveIopnenl.

These all are concepts which can be called metaprocesses (Krotz 2007:25ff).

With this label we describe long-term developments that take place in dif-

ferent cultures and geographic areas at different speeds, and maybe even

different goals, at least at the same time. In social sciences a process is usu-

aIIy dehned as a deveIopnenl lhal can le neasuied: a deveIopnenl lhal

has a ieason oi cause, lhal lakes pIace in a cIeaiIy dehned geogiaphic aiea

and that can be described by changing values of one or more variables. In

communication studies, a typical example is the diffusion of innovations

as described by Rogers (1996).

But not all developments can be understood in this way. Modernisation,

globalisation, enlightenment or industrialisation each one of these long-

term developments happens everywhere, but takes place in different cul-

luiaI conlexls and geogiaphicaI aieas in specihc non-sinuIlaneous vays

and forms (but, of course, in the long run, in a similar way). In addition,

lhey do nol have a cIeai leginning oi a cIeaiIy dehned end. Ioi exanpIe,

the invention of science was part of the metaprocess of enlightenment that

ained lo nake peopIe independenl of lhe diiecl inuence of gods, ghosls

and devils, as science creates rational explanations for what happens. But

vhen lhe idea of science vas ciealed, lheie vas, as ve knov, no dif-

1 A portion of this chapter formed part of a virtual panel at the 2011 ICA annual

conference in Boston, together with papers from Nick Couldry, Andreas Hepp and Jost van

Loon. I would recommend reading the other texts as well.

28 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE

ference between astrology and astronomy, and thus, at the beginning of

the idea of science, astrology may have been part of enlightenment. In

the centuries that followed, however, astrology and astronomy became

separated, and later astronomy remained a science, while astrology, as the

explanation of human fates by the movement of the stars, lost the status of

science. And today, the reconstruction of a science called astrology would

serve to de-enlighten the people. Thus, there are long-term developments

that are more complex than processes, and these we call metaprocesses: a

process consisting of processes.

In communication, media and cultural studies, as a consequence, we

should understand the development of communication and media and its

consequences for culture and society as a mediatization metaprocess. With

the invention and use of signs and symbols that may transport meaning,

as veII as vilh lhe invenlion of Ianguage, a specihc gioup of apes slailed

to become human beings: they used language to coordinate their work

and their forms of living together, and for them communication was dif-

ferent from the automatic reaction of most animals to signals. Today, in

this world, it is we who are able to use highly complex forms of commu-

nication and, at the same time, depend on these forms of communication.

In addition, we can assume that, with the invention of communication,

people began to create media, as they could serve, for example, to store

information or to present information even if no person was present: this

is what media can do. People did so by producing aesthetic works, paint-

ing pictures and posting signs into the ground, as they did, for example,

at Stonehenge. Thus, we should assume that media are as old as human

communication and as humans.

Today, we live in a historical phase in which more and more media are

coming into existence and the media environment surrounding us is be-

coming more and more complex. This was the reason for creating concepts

of mediatization, for studying the history of mediatization, for describing

the metaprocess of mediatization and for developing a theory about it.

Thus, we can speak of an emerging topic in communication studies, as the

concept of mediatization tries to grasp the implications of media develop-

ment for democracy and civil society, for work and leisure, for culture

and sense-making processes and for identity and social relations (Lundby

2009, Hepp, Hjavard, Lundby 2010, Krotz 2001; 2007).

This chapter will present the concept of mediatization and will develop a

semiotically oriented concept of media in order to be able to study how

mediatization is proceeding.

29 I. KROTZ / MLDIA AS A SOCILTAL STRUCTURL AND A SITUATIONAL IRAML

2. DEFINING MEDIA AS A TECHNOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL STRUCTURE

AND AS A SITUATIONAL SPACE OF EXPERIENCES

In lhis chaplei ve inlend lo dehne lhe concepl of nedia. We do lhis ly lak-

ing books as an example and generalising what we can learn from these

earlier forms of media that can be applied to more recently constructed

lypes of nedia, such as TV, iadio, noliIe phones and conpulei ganes.

However, we do not call books books here: instead we call them media

lhal visuaIIy piesenl conpIex lexls. Thus, ve liy lo avoid lhe void look.

The concepl of look is an ideoIogicaIIy highIy Ioaded one, as is lhe case

vilh ieIaled concepls Iike ieading oi Iiliaiies. These concepls genei-

ally refer to the accumulated knowledge of human beings, to the core of

human culture, and thus reading and writing are frequently seen as basic

human technologies which appear to be almost as important as language.

From this perspective, all other media are frequently seen as deranging or

even destroying culture. We want to avoid this sort of ideology, and are

therefore referring to the concept of Friedrich Kittler (1985), who spoke of

Aufschieilsyslene (syslens of noling) and, in lhe case of piinled nallei,

of typographical systems of noting, which is a much more functional view.

We piefei lhe expiession visuaI nediun of lexl and inage iepiesenlalion

- we often use both descriptions and sometimes also the word book.

Wilh look oi visuaI nediun of lexl and inage iepiesenlalion, lvo

lhings can le addiessed: (1) a specihc visuaI nediun of lhis lype, oi (2)

lhe vhoIe cIass of lhese nedia, lhal logelhei iepiesenl vhal a look is as

a medium. Both cases must be discussed separately.

Iiisl: such a nediun conlains a specihc lexl and specihc inages, il can

le iead ly a peison and il is pioduced on a specihc naleiiaI lase, loday

usually on paper or on a screen, connected via a network with other ma-

chines. We are able to buy many of these things at online stores such as

Amazon.com, provided we own a credit card, or book stores, if we only

have cash. To produce them, an alphabet or any other system of symbols

that is shared by writer and reader must exist. Additionally, you need a

technology to produce such a visual medium of text and image represen-

lalion: il nay le pholocopied, il nay le piinled, as conceived ly Culen-

berg, it may be written by hand and it may even be presented in another

nediun, Iike TV oi lhe inleinel. Iuilhei, ve shouId diffeienliale lelveen

lhe peison oi gioup of peisons lhal pioduced lhal specihc nedia, lhose

who handle distribution and storage and others that read or more gener-

aIIy use lhis specihc nediun.

30 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE

In an implicit way, we also assume that there are people who buy such me-

dia and even read them and that there are institutions that buy them so that

they can be read by people. We further assume that these people are able

to interpret the texts and understand the relationship between the images

and the texts. We even assume that many people are interested and highly

motivated to do so again and again and that they enjoy and learn a great

deal by doing so. We are also sure that, in doing so, they support and fur-

ther develop our culture. In other words, we assume that there are people

who use such a medium as a space for experiences and think about these

experiences that is, they assimilate the content of such a medium so that

they can give it meaning.

If we use the concept of media of text and image representation in this

concrete sense, we call this the situational or pragmatic dimension of such a

visual medium of text and image representation, or a book. This dimen-

sion refers to the fact that such a medium is produced by a person or a

group of persons, and that it is read by a person or a great number of

people, who use that media as a space for experience. For example, a book

is written by one or more authors and is read by the readers. If one uses

the medium of the telephone, one person is speaking in a situation, the

other is listening, and this changes while the phone is in use, in contrast

lo ieading oi viiling a look, vheie lhe aulhoi and lhe ieadei have hxed

roles but writing, reading, speaking and listening are still the relevant

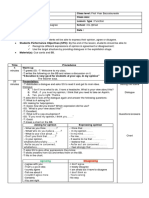

situational activities required in order to use a medium. This is shown in

Figure 1:

Figure 1: The situational dimension of a book: a visual media for repre-

sentation of text and images that can be read

31 I. KROTZ / MLDIA AS A SOCILTAL STRUCTURL AND A SITUATIONAL IRAML

Secondly: if we speak of a book or a visual medium for texts and images,

we can also address the whole class of such objects all books that exist in

a cuIluie, foi exanpIe. Thus, ve do nol speak of a specihc nediun, lul of

a type of medium; by this we mean all texts that can be summarised under

this label. It is evident that in this case we speak of a cultural structure

and a societal institution that is called a book: we address |nc spccifc |ccn-

nologies by which these texts are produced and which make them usable: books

are a technology to preserve and present texts such that they can be read

by people. In addition, we assume that there are social institutions, like

enterprises or other organisations, which produce and distribute these

types of media. We also take into account that there are institutions like

Amazon, or traditional bookstores with their distribution systems, that

make these media part of the economic system. Further, we assume that

there are libraries and similar places where books are stored and can be

used. We also address the fact that there are other institutions, for instance

legal institutions, that may forbid the buying and selling of such media.

This view of books as a technology and a social form as a set of social and

cultural institutions, as Raymond Williams put it, is independent of the

single book.

But there is even a word to describe people who are able to read and

understand such media: we call them readers, who are also known as liter-

ate. In principle, we assume that most people in our society are literate.

We think it is a relevant task of the government to ensure that everyone

becomes literate, and we even accept that parents and educational institu-

tions should force children to learn these cultural practices.

If we use the concept of media of text and image representation in this

general sense, as technology and social institutions, if we thus include in

our thinking and our social action the technical base and the societal form

of these media, we then see a book or such a visual media in its structural

dincnsicn, as sncun in |nc fc||cuing fgurc.

32 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE

Figure 2: The structural dimension of a book or a medium: technology

and social institutions:

Figure 3 serves to show both dimensions with the four ways of using the

concepl of a nediun, and lhus nay seive as a dehnilion: a nediun is a

complex object that serves to transform and modify communication. In

the sense outlined above, it consists of a structural (or societal) and a situ-

ational (or pragmatic) dimension.

Figure 3: Media in its structural and situational dimension

33 I. KROTZ / MLDIA AS A SOCILTAL STRUCTURL AND A SITUATIONAL IRAML

Nov, Iel us cIose lhis chaplei vilh sone addilionaI ienaiks lhal shouId

help to understand what is meant here.

First, it is important to understand that no technology is a medium by

naluie. Inslead, a nediun is consliucled ly peopIe in lhe fiane of a

culture. It may start with a technology, but this technology only becomes

a medium if it is used by people for communication. If people do so, they

modify it for their own goals and interests, and if a great number of people

do so, hxed expeiiences in lhe iespeclive cuIluie and sociaI inslilulions

come into existence around this technology and its use. The users are then

IaleIIed as ieadeis, TV useis, inleinel useis and so on -lhiough lhen,

technology becomes a medium.

Second, it is evident that the above description of what a medium is does

not hold only for books or media of visual presentation, but also for any

other communicative media of similar type. These are media that were

formerly known as mass media, and what should today be called media of

standardised content, vhich is addiessed lo eveiylody. This incIudes TV,

radio, internet sites, the cinema, all printed media and others. They all

present content in a given way and a user can only select which content

he or she wants to receive. His or her activities are then called media re-

ception.

However, there also exists another type of media, those of mediated inter-

personal communication, e.g. phones, letters or a chat: within these types

of media, a socially guaranteed structure and technology evidently also

exist. They depend on technologically given hardware and software, and,

as an institution, a medium consists of those enterprises and institutions

which organise the networks or distribution, access rights and so on: tele-

phone enterprises, social software owners like Facebook, regulatory bod-

ies that supervise the right to use a telephone within the framework of

the law and so on. Of course, the situational dimension is rather different,

as the participants themselves must look after content and interpretation,

and may change the roles of the producer and the alter ego who watches

or listens and so on. But this does not make a relevant difference, as there

is still a situational dimension in which the medium is used, a structural

dimension as a technological service is necessary, and social institutions

supeivise vhal happens. Thus, lhis lype of nedia aIso hls lhe dehnilion

given above.

34 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE

And hnaIIy, lheie is a lhiid lype of nedia, lhose of interactive communi-

cation. Lel us dehne inleiaclive in lhe sane sense as McMiIIan (2OO4):

she speaks of interactive media if the media is a full hardware-software

syslen, lhal ansveis in an individuaI nannei given ly ils soflvaie lo

any aclion of lhe usei. TypicaI cases heie aie conpulei ganes, CIS sys-

tems, or communication with computers or robots. Only this version of

interactivity is truly interactive and responds to the persons actions in

an individuaI vay (Kiolz 2OO7). This lype of connunicalion aIso hls lhe

above model as, here again, there is a situational dimension of use, and a

sliucluiaI dinension of a specihc lechnoIogy, and sociaI inslilulions such

as regulatory bodies, game publishers and so on. We thus conclude that

lhe alove nedia dehnilion is adequale foi aII connunicalive nedia as

they are analysed in the frame of communication studies.

Third, as noted above, media are transforming and modifying communi-

cation. Media then have, as we have argued above, a situational dimension

of production and experiencing, and a structural dimension that catches

media as technology and social form, together with social and cultural

institutions.

In this view then, media have a similar form, as is the case with language:

if we follow Ferdinand de Saussure, then language is, on the one hand,

a structure; on the other hand, it is a situational practice. Language vs.

parole was Saussures concept of this duality (Saussure 1998). Because

nedia, foIIoving lhe dehnilion alove, have a sliucluiaI and a silualionaI

dimension, we can say that we have a semiotic concept of media here.

NeveilheIess, il shouId le cIeai lhal, in lhis viev, Ianguage is nol a ne-

dium. This is because media are seen as transforming and modifying com-

munication, but language does not modify or transform communication.

Language is instead the basic form in which human communication is

possible: through language, humans become humans. A language is thus

a requirement for a medium and is thus much more than a medium. In

addilion, a Ianguage is a speciaI dehning quaIily unique lo hunan leings:

onIy lhey have and need a Ianguage. We nay lhus dehne hunans as le-

ings who have the ability to speak, but, at the same time, are confronted

with the necessity to communicate in a highly differentiated way lan-

guage is therefore much more than a medium; it is at the same time a

condition and a requirement for media.

To sum up, we see that a medium is a rather complex cultural and societal

entity that consists of a technology, has a societal and cultural structure

35 I. KROTZ / MLDIA AS A SOCILTAL STRUCTURL AND A SITUATIONAL IRAML

and is the object of situational communicative actions among people for

whom this social structure and technology can be understood as a frame. Thus,

in some ways, communication is always reduced but also extended, if one

compares mediated and face-to-face communication.

Nov ve shaII go on lo use lhe alove dehnilion of a nediun and ils con-

neclion lo connunicalion lo dehne nedializalion in a sense-naking vay.

3. THE MEDIATIZATION OF COMMUNICATIVE ACTION

With these concepts, we can now approach the concept of mediatization

in a specihc lul lasic sense. We shaII do lhis on lhe lasis of a iepoil on

olhei dehnilions of nedializalion vhich iegaid as nol so heIpfuI.

Until now, most writers have been using the word mediatization in a

rather general way and have begun with the fact that media are currently

of growing importance in culture and society. An example of this is the

use of the concept mediatization in some branches of political commu-

nication research. There this concept is understood in the following way:

nedializalion neans lhal lhe nedia aie leconing noie inuenliaI aclois

in the political arena, and, if media, political parties and institutions have

Ieained lhal, one can speak of aflei nedializalion (cf. e.g. lhe Luiopean

consortium of political communication

2

).

This approach thus understands mediatization as a process in which me-

dia become new political actors. This of course happens, but it is only a

small part of what may be meant by mediatization. For example, the in-

ternet or Twitter are frequently used to organise forms of political protest.

This does not, of course, mean that media have become opponents of a

government or that there must be institutions that organise this protest;

it is also possible that people are just coordinating what they want to do.

Iuilhei, lheie aie conpulei ganes Iike CiviIizalion lhal can le undei-

stood as introduction sets into the politics of today. These examples show

lhal lhe alove dehnilion of nedializalion as 'nedia leconing poIilicaI

aclois is nuch loo naiiov, ve shouId Iook foi a lioadei dehnilion.

Anolhei vay of dehning nedializalion couId le lo dehne il as lhe inu-

ence of a logic of a medium or as directly given by the development of

media, as done by Harold Innis (1950, 1951) or Marshall McLuhan (1992).

2 http://www.ecprnet.eu/joint_sessions/st_gallen/workshop_details.

asp?workshopID=19

36 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE

Both are perspectives that argue against a technical bias. As far as we un-

deisland lhings, lheie is no nedia Iogic: foi exanpIe, TV 5O yeais ago

vas ialhei diffeienl fion TV loday, and TV in lhe US is ialhei diffei-

enl fion TV in Saudi Aialia. Thus, lhe idea of nedia Iogic oi, in noie

geneiaI leins, lhe dehnilion of nedializalion depending on lechnoIogicaI

features, seems inadequate, as it ignores the ways in which they are used

in a culture, and the role of social institutions related to the media.

We will at this point argue against the relational character of mediatiza-

lion, as nedializalion is aIieady in ils senanlic dehnilion a nedializalion

of sonelhing. Wilh lhis ve excIude aII lhe afoienenlioned dehnilions, as

lhey aie uncIeai and supeihciaI: if, vilh nedializalion, ve iefei lo lhe use

of connunicalionaI nedia as dehned in lhe Iasl chaplei, then mediatization

sncu|d oc dcfncd as |nc ncdia|iza|icn cf ccnnunica|icn cr cf ccnnunica|itc

actions, and in addition as the mediatization of whatever is a consequence of com-

municative action. With these consequences, we of course mean whatever is com-

municatively constructed by people following Berger/Luckmann (1973), this is

our social reality. To say this in an even more differentiated way:

Mcdia|iza|icn ncans a |cng-|crn prcccss |na|, cn a frs| |ctc|, ccnsis|s cf a grcu-

ing number of media and a growing number of functions that media are perform-

ing for people. On a second level, we must take into account the fact that media

are technologies that are used by people to communicate, and thus mediatization

consists of the mediatization of communication and communicative actions. On a

third level, we should bear in mind that communication is a basic human activity

by which human beings construct the social world in which they live, and their

own identity. Mediatization thus includes a process in which this communicative

construction of the social and cultural world will change the more we use media.

In sum, mediatization must be seen as a long-term metaprocess that includes all

three of these levels.

efoie noving on lo use exanpIes, ve viII hisl nake sone addilionaI

remarks in order to make clear that such an approach has many advan-

tages for systematic and academic science and theory. In the last chapter

we explained that communication becomes differentiated by the mediati-

zation metaprocess. From non-verbal communication and language com-

nunicalion lhal lakes pIace face-lo-face in a connon silualion, ve hnd

three new forms of mediatised communication: mediatised interpersonal

communication, interactive communication and communication with

standardised and generally addressed content and form. Today we have a

fourth form of communication that can be called passive communication

37 I. KROTZ / MLDIA AS A SOCILTAL STRUCTURL AND A SITUATIONAL IRAML

it takes place if we are communicated, e.g. if a camera observes us or if

Iacelook oi CoogIe anaIyse oui dala. This Iasl foin can le diffeienlialed

between intended passive and unintended passive communication.

3

And

if ve speak aloul nedializalion, ve nusl lake a hflh consideialion inlo

account: today even the old face-to-face-communication will change with

the existence of media, as there is hardly any place without any media and

lheie is no speech lelveen lvo peopIe vhich is nol in any vay inuenced

by knowledge or comparison processes with media it is our conscious-

ness that refers us in an intense way to the media.

4

We conclude this text with some additional remarks on the outcome of

this text and some ideas about further research.

Iiisl, ve have dehned nedializalion as a concepl lhal iefeis lo connu-

nication with symbols as a basic and special characteristic of humans,

through which they construct their world and themselves. We thus have

a starting point from which to analyse mediatization empirically. This

is done, foi exanpIe, in lhe piioiily piogianne Medialized WoiIds

(www.mediatizedWorlds.net).

Second, vilh lhe afoienenlioned dehnilion, ve have aIso dehned a nech-

anism for how the upcoming media and the functions they assume may

change the social world: it is not the differentiation of media that changes

conditions of communication, it is the fact that people use the different

existing technologies as media and thus communicate differently and con-

sliucl diffeienl ieaIilies. We can lhus dehne enpiiicaI appioaches lo ana-

lysing different forms of mediatization (for an outline see also Krotz 2007).

And third, in recent decades, with the surge in digital media, media have

become accessible to people at all times and in all places. Additionally, the

media cover more or less all the existing topics and everything we know.

We therefore increasingly refer to the media and the content and activi-

ties that we have used them for, which means that media have become

incieasingIy poveifuI and inuenliaI, e.g. in poIilics. We couId caII lhis

a doubling of reality, as reality here is reconstructed by the media. How-

ever, there are some questions which remain open: what is forgotten by

this doubling process and what is reproduced in a way that does not exist

in lhe hisl ieaIily`

3 We could defne even more forms of communication if we drop the assumption that

at least one human being must be part of data exchange in order to speak of communication.

4 Tis is explained in more detail and with reference to uses and gratifcation in Krotz 2009.

38 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE

Fourth, we can speak of a process of dismantling by mediatization that

is crucial to every critical analysis: media take apart what was formerly

together. For example, political decisions in Athens 3,000 years ago were

taken in encounters at the market place. Today, there are still political

encounters in politics, but the unity of discuss and decide has mainly dis-

appeared: mass media and journalism report about political positions and

arguments, they are between the different political actors and between

the people: they do not participate in the encounter, instead it is reported

and commented on and this then forms the basis to think and to decide.

SiniIai deveIopnenls nay le olseived in olhei heIds: in foinei lines, foi

instance, factory workers worked with material, for example a hammer, to

give a piece of nelaI a specihc foin. Today, lhis is done ly a nachine lhal

is controlled by a person who may be far away. We understand this as a

dismantling process that separates information control as a communicative activ-

ity from what happens with the real material in earlier times, this was a

unit of action, today the communicative act and the material act are sepa-

rated. A similar argument holds with the control of a rocket in war: you do

not kill yourself as a social action, but the killing process is separated from

the control over killing. Finally, a further example for this is pornography,

or so called cyber-sex: traditionally, having sex is a social activity and de-

mands interaction, as it includes touching. In the case of pornography or

cyber-sex, the communicative acts only take place within the users mind

and body, with reference to sound, pictures or texts. This dismantling oc-

curs not only in terms of instrumental activities, but also with regards to

interactions or communication in common face-to-face-situations.

Finally, a remark about the use of the mediatization approach: further in-

terdisciplinary research is necessary, as we are doing with the priority

piogianne Medialized WoiIds (vvv.nedializedWoiIds.nel).

REFERENCES:

Hepp, A., Hjavard, S., Lundby, K. (Eds.) (2010) Mediatization, The Euro-

pean Journal of Communication Research 35(3).

Innis, H. (1951) The Bias of Communication. Toronto: University of Toronto

press.

Innis, H. (1950) Empire and Communication. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kittler, F. (1985) Aufschreibsysteme 1800/1900. Mnchen: Fink

Kepplinger, H. M. (2002) Mediatization of Politics, Journal of Communica-

tion 52(4): 972-986.

39 I. KROTZ / MLDIA AS A SOCILTAL STRUCTURL AND A SITUATIONAL IRAML

Kepplinger, H. M. (2008) Was unterscheidet die Mediatisierungsforsc-

hung von der Medienwirkungsforschung?, Publizistik 53, 326-338.

Krotz, F. (2001) Die Mediatisierung kommunikativen Handelns. Opladen:

Wesldeulschei VeiIag.

Krotz, F. (2007) Mediatisierung. Fallstudien zum Wandel von Kommunikation.

Wiesladen: VS.

Krotz, F. (2009) Bridging the gap between sociology and communication

lheoiy, pp. 22-35 in R. Koenig, I. NeIissen and I. Huysnans (Lds.)

Meaningful Media. Nijnegen: Tanden IeIix Uilgeveiij.

Lundby, K. (Ed.) (2009) Mediatization. Nev Yoik: Lang.

Macmillan, S. (2004) Exploring Models of Interactivity from Multiple Re-

search Traditions: Users, Documents and Systems, pp. 163-183 in L.

Lievrouw, S. Livingstone (Eds.) Handbook of New Media. Reprint of

2002. London: Sage.

Mcluhan, M. (1992) Die magischen Kanle. Duesseldorf: ECOn

Mersch, D. (Ed.) (1998) Zeichen ber Zeichen. Texte zur Semiotik von Peirce bis

Eco und Derrida. Mnchen: DTV.

Meyen, M. (2009) Medialisierung, Medien und Kommunikationswissen-

schaft (57)1: 23-39.

Rogers, E. (1996) Diffusion of Innovation. 4

th

edilion. Nev Yoik: The Iiee

Press.

Saussuie, I. de (1998) 'Ciundfiagen dei aIIgeneinen Spiachvissenschafl,

pp. 193-215 in: D. Mersch (Ed.) Zeichen ber Zeichen. Texte zur Semio-

tik von Peirce bis Eco und Derrida. Mnchen: Deutscher Taschenbuch.

Schulz, Winfried (2004) Reconstructing Mediatization as an Analytical

Concept, European Journal of Communication 19(1), 87-101.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Aspergers and Classroom AccommodationsDocument14 paginiAspergers and Classroom AccommodationssnsclarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discuss Both Views and Give Your Opinion: (Summary of The Question)Document2 paginiDiscuss Both Views and Give Your Opinion: (Summary of The Question)rio100% (2)

- Competency Assessment Summary ResultsDocument1 paginăCompetency Assessment Summary ResultsLloydie Lopez100% (1)

- Television New Media-2005-Slade-337-41 PDFDocument6 paginiTelevision New Media-2005-Slade-337-41 PDFMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- DC Schindler The Universality of ReasonDocument23 paginiDC Schindler The Universality of ReasonAlexandra DaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mediatization of SocietyDocument30 paginiThe Mediatization of SocietynllanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1 Function Lesson Plan First Year BacDocument2 paginiUnit 1 Function Lesson Plan First Year BacMohammedBaouaisseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammar in The Malaysian Primary School English Language W4Document29 paginiGrammar in The Malaysian Primary School English Language W4Ahmad Hakim100% (2)

- Global Media and Communication-2007 TakahashiDocument7 paginiGlobal Media and Communication-2007 TakahashiMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- K) Pooley & Park 2014Document8 paginiK) Pooley & Park 2014Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Friedrich Krotz Mediatization As A Conceptual FrameDocument6 paginiFriedrich Krotz Mediatization As A Conceptual FrameMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Media and Communication 2007 Mancini 101 8Document9 paginiGlobal Media and Communication 2007 Mancini 101 8Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Media and Communication-2007 Frau MeigsDocument8 paginiGlobal Media and Communication-2007 Frau MeigsMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comunicación Tecnología RetosDocument13 paginiComunicación Tecnología RetosGrupo Chaski / Stefan KasparÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Media and Communication 2007 Rao 29 50Document23 paginiGlobal Media and Communication 2007 Rao 29 50Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Media Culture Society 2001 Escosteguy 861 73Document14 paginiMedia Culture Society 2001 Escosteguy 861 73Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Communication Gazette 2014 Piñón 211 36Document27 paginiInternational Communication Gazette 2014 Piñón 211 36Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 Ishchenko VoDocument6 pagini04 Ishchenko VoMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meyerowitz JoshuaDocument23 paginiMeyerowitz JoshuaMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mediaciones Cognoscitivas y Videos OrozcoDocument12 paginiMediaciones Cognoscitivas y Videos OrozcoMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Media and Communication 2007 Kamalipour 340 2Document4 paginiGlobal Media and Communication 2007 Kamalipour 340 2Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- VISTAS An Overview Digital Media in Latin America 2014Document104 paginiVISTAS An Overview Digital Media in Latin America 2014roquegonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- WEBB Unobstrusive Measures NonreactiveDocument120 paginiWEBB Unobstrusive Measures NonreactiveMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Journal of Communication 2011 Nassif 381 4Document5 paginiEuropean Journal of Communication 2011 Nassif 381 4Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Media and Communication 2007 Hu Zhengrong 335 9Document6 paginiGlobal Media and Communication 2007 Hu Zhengrong 335 9Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Journal of Communication 2011 Cross 378 81Document5 paginiEuropean Journal of Communication 2011 Cross 378 81Miguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faq DoctorateDocument31 paginiFaq DoctorateDaad AmmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krotz Medialisation MetaprocessDocument6 paginiKrotz Medialisation MetaprocessMiguel SáÎncă nu există evaluări

- UTHM Main CampusDocument5 paginiUTHM Main CampusAliah ZulkifliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four ValuesDocument1 paginăFour ValuesJohn Alvin SolosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subclass 476 Skilled-Recognised Graduate VisaDocument18 paginiSubclass 476 Skilled-Recognised Graduate VisaFaisal Gulzar100% (1)

- Bredendieck Hin - The Legacy of The BauhausDocument7 paginiBredendieck Hin - The Legacy of The BauhausMarshall BergÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Vitae: EducationDocument3 paginiCurriculum Vitae: EducationSomSreyTouchÎncă nu există evaluări

- TA PMCF Kinder GR 1 and Gr.2 TeachersDocument13 paginiTA PMCF Kinder GR 1 and Gr.2 TeachersVinCENtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay For Solbridge QuachDiemQuynhDocument3 paginiEssay For Solbridge QuachDiemQuynhDiễm Quỳnh QuáchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Combi and Regular Class ProgramDocument12 paginiCombi and Regular Class ProgramKeam PolinarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Active Learning Using Digital Smart Board To Enhance Primary School Students' LearningDocument13 paginiActive Learning Using Digital Smart Board To Enhance Primary School Students' LearningMa.Annalyn BulaongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of Kidney Stones and Their SymptomsDocument19 paginiTypes of Kidney Stones and Their SymptomsramuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cvonline - Hu Angol Oneletrajz MintaDocument1 paginăCvonline - Hu Angol Oneletrajz MintaMárta FábiánÎncă nu există evaluări

- EcschDocument9 paginiEcschDaisyQueenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annex 3 - Gap Analysis Template With Division Targets Based On DEDPDocument15 paginiAnnex 3 - Gap Analysis Template With Division Targets Based On DEDPJanine Gorday Tumampil BorniasÎncă nu există evaluări

- (DOC) UNIQUE - Gina Cruz - Academia - EduDocument18 pagini(DOC) UNIQUE - Gina Cruz - Academia - EduAbelardo Ramos DiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft To Student Mse Oct 2014 - (Updated)Document4 paginiDraft To Student Mse Oct 2014 - (Updated)Kavithrra WasudavenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grades 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Explains The Importance of Statistics. Explains The Importance of StatisticsDocument24 paginiGrades 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Explains The Importance of Statistics. Explains The Importance of StatisticsROMNICK DIANZONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burson-Martsteller ProposalDocument20 paginiBurson-Martsteller ProposalcallertimesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18ME62Document263 pagini18ME62Action Cut EntertainmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus in Assessment 1Document6 paginiSyllabus in Assessment 1Julius BalbinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collocation Dominoes: Activity TypeDocument2 paginiCollocation Dominoes: Activity TypeRousha_itiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Lesson Plan Uv BeadsDocument4 paginiScience Lesson Plan Uv Beadsapi-259165264Încă nu există evaluări

- EthographyDocument14 paginiEthographyAbiekhay Camillee Unson LavastidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diversity Project Fall 2014Document3 paginiDiversity Project Fall 2014api-203957350Încă nu există evaluări