Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Haruspices William Smith

Încărcat de

johnharnsberryDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Haruspices William Smith

Încărcat de

johnharnsberryDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.

:

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875.

HARUSPICES, or ARUSPICES, were soothsayers or diviners, who interpreted

the will of the gods. They originally came to Rome from Etruria, whence

haruspices were often sent for by the Romans on important occasions

(Liv. XXVII.37; Cic. Cat. III.8, de Div. II.4). The art of the haruspices resembled in

many respects that of the augurs; but they never acquired that political

importance which the latter possessed, and were regarded rather as a means for

ascertaining the will of the gods than as possessing any religious authority. They

did not in fact form any part of the ecclesiastical polity of the Roman state during

the republic; they are never called sacerdotes, they did not form a collegium, and

had no magister at their head. The account of Dionysius (II), p587that the

haruspices were instituted by Romulus, and that one was chosen from each tribe,

is opposed to all the other authorities, and is manifestly incorrect. In the time of

the emperors, we read of a collegium or order of sixty haruspices (Tac. Ann. XI.15;

Orelli, Inscr. I. p399); but the time of its institution is uncertain. It has been

supposed that such a collegium existed in the time of Cicero, since he speaks of a

summus magister (de Div. II.24);

a

but by this we are probably to understand not a

magister collegii, but merely the most eminent of the haruspices at the time.

The art of the haruspices, which was called haruspicina, consisted in explaining

and interpreting the will of the gods from the appearance of the entrails (exta) of

animals ofered in sacrifce, whence they are sometimes called extispices, and

their art extispicium (Cic. de Div. II.11; Suet. Ner. 56); and also from lightning,

earthquakes, and all extraordinary phenomena in nature, to which the general

name of portenta was given (Valer. Max. I.1 1). Their art is said to have been

invented by the Etruscan Tages (Cic. de Div. II.23; Festus, s.v. Tages), and was

contained in certain books called libri haruspicini, fulgurales, and tonitruales

(Cic. de Div. I.33; cf. Macrob. Saturn. III.7).

This art was considered by the Romans so important at one time, that the senate

decreed that a certain number of young Etruscans, belonging to the principal

families in the state, should always be instructed in it (Cic. de Div. I.41). Niebuhr

appears to be mistaken in supposing the passage in Cicero to refer to the children

of Roman families (see Orelli, ad loc.). The senate sometimes consulted the

haruspices (Cic. de Div. I.43, II.35; Liv. XXVII.37), as did also private persons

(Cic. de Div. II.29). In later times, however, their art fell into disrepute among well-

educated Romans; and Cicero (de Div. II.24) relates a saying of Cato, that he

wondered that one haruspex did not laugh when he saw another. The Emperor

Claudius attempted to revive the study of the art, which had then become

neglected; and the senate, under his directions, passed a decree that the

pontifces should examine what parts of it should be retained and established

(Tac. Ann. XI.15); but we do not know what efect this decree produced.

The name of haruspex is sometimes applied to any kind of soothsayer or prophet

(Prop. III.13.59); whence Juvenal (VI.550) speaks of Armenius vel Commagenus

haruspex.

The latter part of the word haruspex contains the root spec; and Donatus (ad Ter.

Phorm. IV.4.28) derives the former part from haruga, a victim. Cf. Festus,

s.v. Harviga, and Varro, De Ling. Lat. V.98, ed. Mller. (Gttling, Gesch. der Rm.

Staatsv. p213; Walter, Gesch. des Rm. Rechts, 142, 770, 2nd ed.; Brissonius,

De Formulis, I.29, &c.)

Thayer's Note:

a

summus magister (however declined) does not appear anywhere in the online

Latin text of de Divinatione, an established scholarly text. The passage linked,

I.24.52, refers to a summus haruspex, which the Loeb editor, agreeing with our

Dictionary, translates merely in the sense of "most eminent".

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- High School Chemistry Grade 10-12Document486 paginiHigh School Chemistry Grade 10-12Todd95% (39)

- Mithras in Comparison With Other Belief SystemsDocument6 paginiMithras in Comparison With Other Belief SystemsMathieu RBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Descriptions of Jesus Outside of The New Testament: A Sample of Some of The Primary Source Material Ancient HistoriansDocument3 paginiDescriptions of Jesus Outside of The New Testament: A Sample of Some of The Primary Source Material Ancient HistoriansNick HillÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tithe in Ancient IsraelDocument9 paginiThe Tithe in Ancient IsraelRichard RadavichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Midsummer Night's DreamDocument2 paginiMidsummer Night's Dreammizo2411Încă nu există evaluări

- Self-Compassionate LetterDocument2 paginiSelf-Compassionate LetterRitsu Tainaka75% (4)

- The Origin of The Na-Dene Merritt RuhlenDocument3 paginiThe Origin of The Na-Dene Merritt Ruhlenmikey_tipswordÎncă nu există evaluări

- 87866book CopywebDocument54 pagini87866book Copywebmiller999100% (1)

- THE MITHRAISM Freemasonic ConnectionDocument9 paginiTHE MITHRAISM Freemasonic ConnectionAntonius KarasulasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gregory Nazianzen's First and Second Invective Against Julian The Emperor.Document55 paginiGregory Nazianzen's First and Second Invective Against Julian The Emperor.Chaka AdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revivals Golden KeyDocument113 paginiRevivals Golden KeyArnel Añabieza GumbanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documents of The 1898 Declaration of Philippine IndependenceDocument29 paginiDocuments of The 1898 Declaration of Philippine IndependenceSheila Mae Angoluan100% (3)

- EeceDocument22 paginiEeceEugen CiurtinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts and Crafts From Muslim MindanaoDocument37 paginiArts and Crafts From Muslim MindanaoGilbert Obing0% (1)

- Caesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of RomeDe la EverandCaesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of RomeEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (51)

- Tourism Products of NepalDocument176 paginiTourism Products of NepalMahesh Thapaliya50% (2)

- Gladiators & Beast Hunts: Arena Sports of Ancient RomeDe la EverandGladiators & Beast Hunts: Arena Sports of Ancient RomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art of Liver DiviningDocument16 paginiArt of Liver DiviningjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marguerite Donnadieu, Known As Marguerite Duras (4 April 1914 - 3 March 1996)Document2 paginiMarguerite Donnadieu, Known As Marguerite Duras (4 April 1914 - 3 March 1996)Bianca Baican100% (1)

- Maiestas PDFDocument2 paginiMaiestas PDFJoão Victor LannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Glossary - Julius CaesarDocument6 paginiGlossary - Julius Caesarapi-238598354Încă nu există evaluări

- The Second Triumvirate: Exam Tip: Source SkillsDocument3 paginiThe Second Triumvirate: Exam Tip: Source Skillsd cornsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The City of Rome in Late Imperial Ideology. The Tetrarchs, Maxentius, and ConstantineDocument31 paginiThe City of Rome in Late Imperial Ideology. The Tetrarchs, Maxentius, and ConstantineMariusz Myjak100% (1)

- Archaic Triad - WikipediaDocument4 paginiArchaic Triad - WikipediaIgor HrsticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roman Corinth - The Formation of A Colonial Elite - Antony Spawforth (1996)Document16 paginiRoman Corinth - The Formation of A Colonial Elite - Antony Spawforth (1996)annamd100% (1)

- Epictetus and The TyrantDocument11 paginiEpictetus and The TyrantFernanda Lopes de OliveiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Votive Religion at Caere For The History, Sordi, / Rapporti Romano-Ceriti. Nimio Plus: 2. 37. 4 NDocument11 paginiVotive Religion at Caere For The History, Sordi, / Rapporti Romano-Ceriti. Nimio Plus: 2. 37. 4 NVelveret100% (1)

- Thrasyllus PDFDocument19 paginiThrasyllus PDFceudekarnakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vandalism and Resistance in Republican Rome: Penelope J. E. DaviesDocument19 paginiVandalism and Resistance in Republican Rome: Penelope J. E. DaviesJuan GerardiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taylor WatchingSkiesJanus 2000Document41 paginiTaylor WatchingSkiesJanus 2000shuang songÎncă nu există evaluări

- Divine Insinuation in The 'Panegyrici Latini'Document37 paginiDivine Insinuation in The 'Panegyrici Latini'hÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient NEWSmismatics: A Tribute (Penny) To Tiberius by L.A. HamblyDocument2 paginiAncient NEWSmismatics: A Tribute (Penny) To Tiberius by L.A. HamblyLegion Six VictrixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cult Ritual Killings in Ancient Rome - Winter WatchDocument3 paginiCult Ritual Killings in Ancient Rome - Winter WatchFREEDOM Saliendo De La CavernaÎncă nu există evaluări

- JCS: Female Gladiators of The Ancient Roman World: MurrayDocument1 paginăJCS: Female Gladiators of The Ancient Roman World: MurrayDali Khobakhia100% (1)

- Reflections On Cyrus ConfDocument12 paginiReflections On Cyrus ConfDaniel de FrançaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demokratia (10.1086 - 365921)Document2 paginiDemokratia (10.1086 - 365921)Felipe MontanaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Celtic Warrior Class Devotion Boutet PDFDocument25 paginiCeltic Warrior Class Devotion Boutet PDFcodytlse100% (1)

- Lucius Licinius Sura. Emperors' MakerDocument2 paginiLucius Licinius Sura. Emperors' MakerrufussÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor and His VirtuesDocument29 paginiThe Emperor and His VirtuesliufengÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 02 (From The Rise of Greece To The Christian Era)Document236 paginiThe Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 02 (From The Rise of Greece To The Christian Era)Gutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imperial Rome II: Civil Wars and The FlaviansDocument14 paginiImperial Rome II: Civil Wars and The FlaviansAaron KingÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Short Guide To Electioneering (Commentariolum Petitionis) (LACTOR3) (Q. Cicero J. Murrell, D.W. Taylor (Trans.) ) (Z-Library)Document23 paginiA Short Guide To Electioneering (Commentariolum Petitionis) (LACTOR3) (Q. Cicero J. Murrell, D.W. Taylor (Trans.) ) (Z-Library)Daniel HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lee-Stecum - 2006 - Dangerous Reputations Charioteers and Magic in FoDocument11 paginiLee-Stecum - 2006 - Dangerous Reputations Charioteers and Magic in FophilodemusÎncă nu există evaluări

- White GreekTyranny 1955Document19 paginiWhite GreekTyranny 1955Jose Miguel Gomez ArbelaezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seeing Caesar's Symbols. Religious Implements On The Coins of Julius Caesar and His SuccessorsDocument16 paginiSeeing Caesar's Symbols. Religious Implements On The Coins of Julius Caesar and His SuccessorsRubén EscorihuelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Guide Lecture 3.: Numa Pompilius Invented The Traditional Roman Religion. Like Many of The KingsDocument3 paginiStudy Guide Lecture 3.: Numa Pompilius Invented The Traditional Roman Religion. Like Many of The KingsVickyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Johns Hopkins University Press, Classical Association of The Atlantic States The Classical WorldDocument24 paginiThe Johns Hopkins University Press, Classical Association of The Atlantic States The Classical WorldAgatha GeorgescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dyck, Andrew R. - Three Notes On Cicero, in VerremDocument4 paginiDyck, Andrew R. - Three Notes On Cicero, in VerremLyuba RadulovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greek Images of Monarchy and Their Influence On Rome and Alexander To Augustus 1Document319 paginiGreek Images of Monarchy and Their Influence On Rome and Alexander To Augustus 1Jane SatherÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.a Barbara Levick - Morals, Politic, and The Fall of The Roman RepublicDocument11 pagini3.a Barbara Levick - Morals, Politic, and The Fall of The Roman RepublicPram BayuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iv) The Roman Empire: Augustus of Prima Porta IsDocument13 paginiIv) The Roman Empire: Augustus of Prima Porta IsAlbert FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Curse of Roman SlaveryDocument6 paginiThe Curse of Roman SlaveryEve AthanasekouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oliva, The Early Tyranny (1982)Document19 paginiOliva, The Early Tyranny (1982)Keith HurtÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 41) Calcidius - On Platoâ S Timaeus-Harvard University Press (2016)Document794 pagini(Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 41) Calcidius - On Platoâ S Timaeus-Harvard University Press (2016)phr8023lzhÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Ok) Resenha MomilglianoDocument9 pagini(Ok) Resenha MomilglianoJoão Victor LannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar - William ShakespeareDocument4 paginiJulius Caesar - William ShakespearePranav Chheda0% (1)

- Matthew Shaw - Imperial LegitimacyDocument198 paginiMatthew Shaw - Imperial LegitimacyEleonora MuroniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evans-Grubbs and Courtney - 1987 - An Identification in The Latin AnthologyDocument3 paginiEvans-Grubbs and Courtney - 1987 - An Identification in The Latin AnthologyCARLOS SOTO CONTRERASÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eco6828 8309Document4 paginiEco6828 8309JgghjgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tiberius: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument5 paginiTiberius: Jump To Navigation Jump To Searchnatia saginashviliÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Foretaste of Eusebian Panegyricism inDocument32 paginiA Foretaste of Eusebian Panegyricism inThe RearrangerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raymond Van Dam - Remembering Constantine at The Milvian Bridge - Cambridge University Press (2011) - 138Document1 paginăRaymond Van Dam - Remembering Constantine at The Milvian Bridge - Cambridge University Press (2011) - 138ram krishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- App 4Document20 paginiApp 4Tommaso GazzoloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legends of The Greek Lawgivers: Andrew Szegedy-MaszakDocument11 paginiLegends of The Greek Lawgivers: Andrew Szegedy-MaszakDániel BajnokÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Gladiatorial (2010)Document13 paginiThomas Gladiatorial (2010)George GeorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nero in The Medieval French TraditionDocument16 paginiNero in The Medieval French TraditionGabriela HuidobroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some Observations On The Origin of Byzantine-Persian Political SymbiosisDocument13 paginiSome Observations On The Origin of Byzantine-Persian Political SymbiosistheodorrÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Walk With the Emperors: A Historic and Literary Tour of Ancient RomeDe la EverandA Walk With the Emperors: A Historic and Literary Tour of Ancient RomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bewildering Beleaguerment The Problem ofDocument21 paginiBewildering Beleaguerment The Problem ofjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Malone 1971Document23 paginiMalone 1971johnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rosettaproject Acm Vertxt-1Document69 paginiRosettaproject Acm Vertxt-1johnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minov S and Kessel G Recent PublicationsDocument90 paginiMinov S and Kessel G Recent PublicationsjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rewriting Scripture As An Exercise in CDocument20 paginiRewriting Scripture As An Exercise in CjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Nomads in The Near East in LDocument17 paginiThe Role of Nomads in The Near East in LjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Arabic Dialect of Kbese An Oasis DiaDocument1 paginăThe Arabic Dialect of Kbese An Oasis DiajohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- ܫܪܒܢܐ ܣܠܐܦܐ ܘܠܣܠܐܦܘ ܡܕܐܡܬܐDocument1 paginăܫܪܒܢܐ ܣܠܐܦܐ ܘܠܣܠܐܦܘ ܡܕܐܡܬܐjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- King Lists ComparedDocument8 paginiKing Lists ComparedjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- On The Position of Nuristani Within IndoDocument31 paginiOn The Position of Nuristani Within IndojohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loanwords in Phoenician and PunicDocument30 paginiLoanwords in Phoenician and PunicjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- ܐܡܠܠ ܟܝDocument1 paginăܐܡܠܠ ܟܝjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classical Syriac Neo-Aramaic and ArabicDocument17 paginiClassical Syriac Neo-Aramaic and ArabicjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument7 paginiEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- ܦܪܘܐܗ ܡܐܪܝDocument1 paginăܦܪܘܐܗ ܡܐܪܝjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghayhabil GhasaqiDocument1 paginăGhayhabil GhasaqijohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- ܒܘܬܪ ܦܠܩ ܕܫܥܬܐDocument1 paginăܒܘܬܪ ܦܠܩ ܕܫܥܬܐjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2ALAAZA3AMATDocument1 pagină2ALAAZA3AMATjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kadh Den Ethaa Lwoth Mshii7oo Sham3uunDocument1 paginăKadh Den Ethaa Lwoth Mshii7oo Sham3uunjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kama QultDocument1 paginăKama QultjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diwan Haran GauaithaDocument25 paginiDiwan Haran GauaithajohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- ܐܠܐ ܐܢܡܐ ܐܠܕܗܪ ܠܝܠܐܠ ܘ ܐܥܨDocument1 paginăܐܠܐ ܐܢܡܐ ܐܠܕܗܪ ܠܝܠܐܠ ܘ ܐܥܨjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- King Lists ComparedDocument8 paginiKing Lists ComparedjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3ALAQDocument1 pagină3ALAQjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient Migration Patterns To North America Are Hidden in Languages Spoken TodayDocument5 paginiAncient Migration Patterns To North America Are Hidden in Languages Spoken TodayjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of The Babylonian ChroniclesDocument2 paginiList of The Babylonian ChroniclesjohnharnsberryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tell The World of His LoveDocument1 paginăTell The World of His LoveLucky Valera DayondonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhutan: Druk Yul Druk Gyal Khap)Document5 paginiBhutan: Druk Yul Druk Gyal Khap)rat12345Încă nu există evaluări

- Category Wise Colony List PDFDocument46 paginiCategory Wise Colony List PDFjatinderpal singh BhathalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mega 28000 LinksDocument1.190 paginiMega 28000 LinksMonserrat ArguetaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uddhab Bharali 111Document3 paginiUddhab Bharali 111Onkar ChavanÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPOnline's Authorized KIOSK List PDFDocument6 paginiMPOnline's Authorized KIOSK List PDFSunil Dixit100% (1)

- Folk Architecture: Submitted By: Kristine Mae PalaoDocument15 paginiFolk Architecture: Submitted By: Kristine Mae Palaozeno phyxxÎncă nu există evaluări

- "A" ZONA: 175: SelloDocument19 pagini"A" ZONA: 175: SelloHelga ChamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jawaharlal Nehru (MAHARASHTRA), India (CY) - Apapa, Nigeria (CY)Document2 paginiJawaharlal Nehru (MAHARASHTRA), India (CY) - Apapa, Nigeria (CY)r shashi kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA-023040 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (Filipino) - Tuguegarao - 9-2019 PDFDocument25 paginiRA-023040 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (Filipino) - Tuguegarao - 9-2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sanity of Madness in Edward P Jones' The Known WorldDocument4 paginiThe Sanity of Madness in Edward P Jones' The Known Worldneptuneauteur100% (2)

- Bi Bi 2Document19 paginiBi Bi 2Aladetan AbiodunÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Pairs, answe-WPS OfficeDocument2 paginiIn Pairs, answe-WPS Officeeng.hasan.91777Încă nu există evaluări

- Snow White: Fairy Tales For The First TimeDocument8 paginiSnow White: Fairy Tales For The First TimeRehan AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- A UnitDocument127 paginiA UnitLia TahsinÎncă nu există evaluări

- IGOROTDocument18 paginiIGOROTKreizel FajaÎncă nu există evaluări

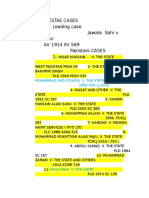

- Evidence Cases ListDocument12 paginiEvidence Cases ListAnam Dawood Hashmi100% (1)

- Level B1Document6 paginiLevel B1Jorge Anibal Rivera CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- UNLESS You Understand Your Role in SocietyDocument2 paginiUNLESS You Understand Your Role in Societyirenemwendeh07Încă nu există evaluări

- Prueba de Seleccion Excel)Document447 paginiPrueba de Seleccion Excel)Paula Daniela GoyenecheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Racharla Junior College Admissions 2012-2013 BatchDocument10 paginiRacharla Junior College Admissions 2012-2013 BatchRANJITH_DOSALAÎncă nu există evaluări