Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

DRYZEK - Policy Analysis As A Hermeneutic Activity

Încărcat de

Remy Løw0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

17 vizualizări21 paginiAny piece of policy analysis must be appropriate to the context of its intended use. Social science often fails as policy analysis due to insensitivity to context. This paper explores a number of different modes of policy analysis to determine the circumstances in which the application of each is appropriate. It is argued that each mode is appropriate only under a fairly limited set of conditions; many of the problems policy analysis encounters are a result of attempts to apply a mode outside its niche. Greater use should be made of what is developed here as a hermeneut!c model of policy analysis, appropriate in a residual set of conditions which none of the traditional models of policy analysis copes with adequately.

Titlu original

DRYZEK_Policy Analysis as a Hermeneutic Activity

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentAny piece of policy analysis must be appropriate to the context of its intended use. Social science often fails as policy analysis due to insensitivity to context. This paper explores a number of different modes of policy analysis to determine the circumstances in which the application of each is appropriate. It is argued that each mode is appropriate only under a fairly limited set of conditions; many of the problems policy analysis encounters are a result of attempts to apply a mode outside its niche. Greater use should be made of what is developed here as a hermeneut!c model of policy analysis, appropriate in a residual set of conditions which none of the traditional models of policy analysis copes with adequately.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

17 vizualizări21 paginiDRYZEK - Policy Analysis As A Hermeneutic Activity

Încărcat de

Remy LøwAny piece of policy analysis must be appropriate to the context of its intended use. Social science often fails as policy analysis due to insensitivity to context. This paper explores a number of different modes of policy analysis to determine the circumstances in which the application of each is appropriate. It is argued that each mode is appropriate only under a fairly limited set of conditions; many of the problems policy analysis encounters are a result of attempts to apply a mode outside its niche. Greater use should be made of what is developed here as a hermeneut!c model of policy analysis, appropriate in a residual set of conditions which none of the traditional models of policy analysis copes with adequately.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 21

Policy Sciences 14 (1982) 309-329

Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam - Printed in the Netherlands

309

Pol i cy Anal ysi s as a Hermeneut i c

Act i vi t y

J O H N D R Y Z E K

Department of Political Science, Ohio State University, 223 Derby Hall, 154 North Oval Mall, Columbus,

OH 43210, U.S.A.

ABSTRACT

Any piece of policy analysis must be appropriate to the context of its intended use. Social science often fails

as policy analysis due to insensitivity to context. This paper explores a number of different modes of policy

analysis to determine the circumstances in which the application of each is appropriate. It is argued that

each mode is appropriate only under a fairly limited set of conditions; many of the problems policy analysis

encounters are a result of attempts to apply a mode outside its niche. Greater use should be made of what is

developed here as a hermeneut!c model of policy analysis, appropriate in a residual set of conditions which

none of the traditional models of policy analysis copes with adequately.

If it rained knowledge, I'd hold out my hand; but I would not give myself the trouble to go in quest of it

(Dr. Samuel Johnson. Quoted in Boswell's Life of Johnson)

I. I n t r o d u c t i o n

Unf or t unat el y for Dr. J ohns on, it rarel y rai ns knowl edge. Even when it does, many

peopl e choose to hol d an umbr el l a over t hei r head, i nst ead of hol di ng out t hei r hands.

Thus one fi nds social scientists devot i ng consi der abl e effort to the pr oduct i on of

knowl edge i nt ended to be appl i cabl e to publ i c policy, onl y to have little heed paid to

t hei r efforts by peopl e in publ i c deci si on maki ng posi t i ons, or pol i cy st akehol ders

more general l y. We have i ndeed t ravel l ed far from the heady days of the 1960s, when it

was widely believed t hat , gi ven enough anal ysi s and federal gover nment money, it was

possi bl e to solve any social pr obl em. Today, one fi nds wi despread doubt a mong bot h

pol i cymaker s and social scientists - not least policy anal yst s t hemsel ves - concer ni ng

the abi l i t y of social science to cont r i but e to social pr obl em sol vi ng [1].

0032-2687 / 82/0000-0000 / $02.75 9 1982 Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company

310

The fai l ure of soci al science research t o cont r i but e t o pol i cy choi ce has elicited t wo

f r equent react i ons. The mor e cyni cal woul d hol d t hat soci al scientists shoul d st op

t ryi ng. For exampl e, Li ndbl om and Cohen (1979, p. 92) write t hat , when a social

sci ent i st is t hi nki ng of doi ng a piece of pol i cy anal ysi s, "t he most f r equent l y appl i cabl e

pr escr i pt i on f or hi m is ' St op! ' , " on t he gr ounds t hat the nor mal fat e of any piece of

anal ysi s is to get lost in the give and t ake of politics. Al t ernat i vel y, one mi ght cast

anal yst s as oper at i ng officials whose pr i mar y concer n relates to the or gani zat i on t hey

wor k f or and its cont i nued heal t h (see Wi l davsky, 1979), as opposed t o social pr ob-

lems.

Is t here any al t er nat i ve t o cyni ci sm on the one hand and s ycophancy on the ot her?

The chal l enge is t o carve out a const r uct i ve rol e f or social science and pol i cy anal ysi s

while recogni zi ng the real i t y of deci si on processes: i nt eract i ve, pol i t i cal , and char act er -

ized by the presence of a mul t i pl i ci t y of st akehol der s wi t h perspect i ves di fferent f r om

one a not he r and f r om t hat of t he anal yst . My i nt ent i on here is t o rise to this chal l enge

t hr ough t he exami nat i on of a numbe r of di fferent modes of pol i cy anal ysi s and the

i dent i fi cat i on of t he ci r cumst ances in whi ch the appl i cat i on of each is appr opr i at e. In

so doi ng, I will ar gue f or mor e ext ensi ve use of what I will call a " her meneut i c" model

of the act i vi t y.

Pol i cy anal ysi s as a field is cur r ent l y di vi ded and i ncoherent . The divisions r un deep;

the field has no accept ed par adi gm, wel l -devel oped body of t heor y, or set of met hods

to appl y t o specific pol i cy pr obl ems. Indeed, defi ni t i ons of pol i cy anal ysi s are al mos t

as numer ous as pol i cy anal yst s. I will t ake the defi ni t i on offered by Dunn (1981, p. 35):

Policy analysis is an applied social science discipline which uses multiple methods of inquiry and

argument to produce and transform policy-relevant information that may be utilized in political settings

to resolve policy problems.

The key poi nt s, whi ch this defi ni t i on emphasi ses, are t hat pol i cy anal ysi s di f f e r s

f r om " pur e" soci al science in t hat i nf or mat i on needs t o be t ransf ormed as well as

pr oduced, and t hat its use in pol i t i cal set t i ngs is not a secondar y consi der at i on, but a

pr i ma r y aspect of t he anal ysi s itself. Soci al science may fai l as pol i cy anal ysi s if it fails

to address its pol i t i cal setting. Thi s set t i ng in t ur n is defi ned by the val ue or i ent at i ons

of act or s, t he const r ai nt s upon these act ors, and the st r uct ur e of t hei r reasoni ng.

Here, t he epi st emol ogi cal l y inclined will recogni ze echoes of t he phenomenol ogi cal

cri t i que of mai ns t r eam behavi or al soci al science (see, f or exampl e, Bernst ei n 1976:

115-169). Phe nome nol ogy sees i ndi vi dual s as agent s act i ng in social si t uat i ons in

pursui t of t hei r goal s, as opposed t o dat a poi nt s f or t he t est i ng of hypot heses about

causal l i nkages in the i nt erest s of est abl i shi ng an empi r i cal l y veri fi ed body of t heory.

Phenomenol ogi cal expl anat i ons rely upon an under st andi ng of the logic of the

si t uat i on in whi ch i ndi vi dual s find t hemsel ves. For i ndi vi dual s are capabl e of act i on

based on an under st andi ng of t hei r ci r cumst ances in a way t hat t he obj ect s of nat ur al

science are not . Gener al i zat i on in social science is a chi mer a, as all si t uat i ons are

different.

311

Good exampl es of the phenomenol ogi cal style in social research are the works of

Moyni han (1965; see also Fischer, 1980, p. 137) and Banfield (1970) on race and pover-

ty, and Schuman (1982) on hi gher educat i on. Moyni han and Banfield bot h offer imag-

i nat i ve r econst r uct i ons of t he life si t uat i on of ghet t o dwellers. Schuman at t empt s to

bui l d an under st andi ng of the f unct i ons and meani ng of hi gher educat i on f r om the

perspect i ve of t he i ndi vi dual s subj ect t o it. Whet her these r econst r uct i ons are correct or

mi st aken [2], t hey penet r at e to a level of under st andi ng i mpossi bl e in or di nar y

behavi oral research.

The phenomenol ogi cal cri t i que of social science applies af or t i or i to policy analysis,

which must not onl y seek an under st andi ng of the social and political world, but, in its

appl i cat i on, must also make the connect i on back t o t hat worl d to be pai d any heed by

pol i cy st akehol ders [3]. All t oo often, pol i cy analyses are rejected on the grounds of

t hei r limited relevance to the si t uat i on as defined by those st akehol ders.

One shoul d not i nf er f r om this t hat pol i cy analysts shoul d discard t hei r existing

t ool s and si mpl y adopt phenomenol ogy as met hod. However, t he phenomenol ogi cal

cri t i que does poi nt to the overarchi ng i mpor t ance of mat chi ng analysis to cont ext ;

which, in t urn, suggests a st andar d of " appr opr i at enes s " by which we can j udge bot h

specific pi eces of analysis and di fferent modes of analysis. The focus here is on the

latter.

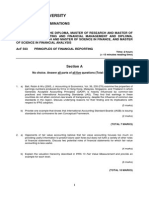

Six such modes will be addressed. These are pol i cy eval uat i on, advocacy, single

f r amewor k, social choice, mor al phi l osophy, and the hermeneut i c model. These six

model s cover much (if not most ) of what has been pr oposed in the name of pol i cy

analysis in t he recent past: each stresses a somewhat di fferent facet. Consi der agai n

Dunn' s definition, with some emphases added:

pol i cy anal ys i s is an appl i ed soci al sci ence di sci pl i ne whi ch uses mul t i pl e methods of inquiry and

argument t o pr oduc e a nd transform pol i cy r el evant i nf or ma t i on t hat ma y be utilized inpolitiealsettings

to resolve policy problems.

The italicized t erms cover t he basic el ement s of pol i cy analysis. One mi ght add, t oo,

t hat the resol ut i on of pol i cy probl ems must be j udged accor di ng to some value(s).

Pol i cy analysis in pract i ce is r ar el y as compr ehensi ve as Dunn' s defi ni t i on specifies.

Inst ead, di fferent pieces of analysis - and di fferent modes of analysis - stress di fferent

aspects of this definition. Each of the italicized t erms is capabl e of provi di ng the

backi ng f or one of the six modes of policy analysis dealt with here, as follows:

Anal ysi s Stresses:

Resol ut i on of pr obl em

Met hods of ar gument

Met hods of i nqui ry

Political setting

Values

Tr ans f or mat i on and ut i l i zat i on

of i nf or mat i on ( communi cat i on)

Mode l

1. Pol i cy eval uat i on

2. Advocacy

3. Single f r amewor k

4. Social choi ce

5. Mor al phi l osophy

6. Her meneut i cs

312

I will descri be these model s and at t empt to i dent i fy the ci rcumst ances in which the

appl i cat i on of each is appr opr i at e. The i nt ent i on is not t o demonst r at e t he uni versal

superi ori t y of t he sixth alternative. What I will suggest, however, is t hat each of models

1-5 is appr opr i at e onl y wi t hi n a fai rl y nar r ow range of ci rcumst ances. Any at t empt t o

appl y any one of t hem beyond its ni che causes the ideal t ype t o meet the nor mal fate of

any over - ext ended paradi gm: a " de a t h of a t housand qual i fi cat i ons" (see Mast er man,

1970). My cont ent i on is t hat t here exists a large residual cat egory oLci rcumst ances in

which none of model s 1-5 per f or ms t oo well, and f or which the hermeneut i c model is

most appr opr i at e.

The first five model s can onl y be deal t with manageabl y as ideal types; but t o

demol i sh each on the basis of its mor e simplistic and naive pract i t i oners woul d be

futile. St r awmen are easily f ound within each t radi t i on, but each also has its more

persuasi ve exponent s, its exempl ar y successes as well as failures. A cl ari fi cat i on of the

condi t i ons f or successful appl i cat i on shoul d offer a f r amewor k f or the intelligent use

of the best t hat the five model s have to offer.

| I. An Assessment of Five Modes of Policy Analysis

Tur ni ng now t o cri t eri a f or t he assessment of these di fferent modes of pol i cy analysis,

it was poi nt ed out above t hat t he phenomenol ogi cal ar gument suggests "appr opr i at e-

ness" as an overal l st andard. It is in this vein t hat Lasswell (1971) proposes policy

sciences as "cont ext ual , mul t i - met hod, and pr obl em- or i ent ed. " Cont ext ual i t y means

t hat analysis shoul d be sensitive t o t he real i t y of t he pol i cy process in whi ch its

cons umpt i on is sought (Lasswell, 1971, pp. 22-23); analysis based upon a mi st aken

image of this process and t he capabilities of t he act ors within it fails t he test. One might

add t hat cont ext ual i t y shoul d also appl y t o t he real i t y of any social si t uat i on t o whi ch

t he concl usi ons of analysis are supposed to apply; this is of especial relevance in the

case of policies and pr ogr ams with an i dent i fi abl e t arget popul at i on (i.e., most

quest i ons of social policy). Pr obl em or i ent at i on requires t hat analysis be t arget ed at

t he real concer ns of st akehol ders wi t hi n t he pol i cy process, and hence percei ved as

rel evant to t hose concerns. Analysis shoul d deal with real worl d probl ems, not

cont ri ved ones.

However , pol i cy analysis needs to be somet hi ng mor e t han cont ext ual and probl em-

ori ent at ed. As an appl i ed discipline, its pur pose is t o cont r i but e t o t he i mpr ovement of

condi t i ons in the real world. An addi t i onal cri t eri on shoul d t herefore be the ext ent t o

which a mode of analysis is capabl e of i dent i fyi ng change in a positive di rect i on [4].

Analysis shoul d be appl i cabl e in policy choice, r at her t han merely rel evant t o it; it

shoul d be capabl e of establishing empi ri cal connect i ons bet ween pol i cy al t ernat i ves

and desired ends. " I mpr ovement " must, of course, be adj udged accordi ng to some

val ue or values; a non- ar bi t r ar y way of i dent i fyi ng these values is requi red. Pol i cy

pr obl ems are nor mal l y charact eri sed by confl i ct i ng values, such t hat agr eement on the

ends or pur poses of pol i cy is difficult t o reach. Indeed, if values did not conflict, pol i cy

313

probl ems woul d be mere technical exercises in execut i on [5].

Our list of criteria is now compl et e, and is as follows:

I. Cont ext ual i t y: Sensitivity to policy process.

Sensi t i vi t y t o social situation.

2. Pr obl em ori ent at i on: Rel evance to real concerns of st akehol ders.

3. Capaci t y t o i dent i fy positive change:

Empirical i dent i fi cat i on.

Non- ar bi t r ay means f or i dent i fyi ng values.

1 believe t hat these cri t eri a const i t ut e a relatively uncont r over si al list, one t hat most

writers who have cont empl at ed the l arger quest i ons of pol i cy analysis coul d accept.

Looki ng ahead, I will at t empt to demonst r at e t hat model s 1-5 can satisfy all t hree cri-

t eri a onl y in a restricted range of ci rcumst ances, leaving a subst ant i al cat egor y of cases

which call f or the her meneut i c alternative.

Model One: Policy Evaluation

In many ways, the defi ni ng charact eri st i cs of the policy eval uat i on model cor r espond

to t he el ement s of r at i onal t hought in i ndi vi dual decision. Its i nj unct i ons are fourfol d:

(i) Speci fy the criteria against which pol i cy out comes are to be j udged;

(ii) Ident i fy a set of policy options;

(iii) Det ermi ne how well each opt i on per f or ms accor di ng to each criterion;

(iv) Choose the opt i on t hat scores best accor di ng to some weighted sum of these

criteria.

The basic idea, t hen, is to establish causal rel at i onshi ps bet ween mani pul abl e policy

vari abl es and cr i t er i on variables. A great deal of work in pol i cy analysis fol l ows this

al~proach [6]. Pr ogr am ( or i mpact ) eval uat i on is a special case in which onl y one

opt i on - chosen in the past and act ual l y being carri ed out - is moni t or ed and assessed.

Mor e general l y, pol i cy eval uat i on can be f or war d or backwar d l ooki ng; exper i ment al

designs are especially useful.

The i mager y of the pol i cy eval uat i on model has the pol i cy anal yst advising a

rat i onal act or who, faced with a policy probl em, is capabl e of purposi ve and effective

act i on in pursui t of some well-defined end or ends. The i mpl i cat i on is t hat public

pol i cy is a f or m of social engi neeri ng, i nf or med by well-defined goals, and t hat the

pr oper role f or the anal yst is t hat of a consul t ant to social engineers.

How realistic is this social engi neeri ng i magery? Pol i cy processes in decent ral i zed

pol i t i cal syst ems - such as t hose in t he Uni t ed States - are t ypi fi ed by a mul t i pl i ci t y of

act or s and interests, such t hat t her e is no overal l gui di ng intelligence capabl e of

rat i onal , pur posi ve act i on. Rat her , policies are made by - or, rat her, emerge f r om -

314

i nt eract i ve political processes (see Li ndbl om, 1959; Wi l davsky, 1979b). The f r equent

fat e of pol i cy eval uat i on is to sink i nt o a political quagmi re. Thus the social engineer-

ing i mage will r ar el y capt ur e reality; t he i mpl ement at i on process is very likely where

any realized pol i cy act ual l y gets made. The policy eval uat i on model will t her ef or e

oft en fall short on t he cont ext ual i t y criterion.

One mi ght expect t he policy eval uat i on mode t o per f or m well on the pr obl em- or i en-

t at i on cri t eri on, given its i magery of advi ce to a pol i cy- maker conf r ont i ng a well-de-

fined pr obl em. However , this will be the case onl y if t here is consensus among

st akehol ders as t o t he nat ure of the policy probl em. Again, real world policy disputes

are as much about pr obl em defi ni t i on as t hey are about al t ernat i ve ways of solving a

pr obl em (see Dunn, 1981, pp. 97-102).

Tur ni ng t o means f or the i dent i fi cat i on of values, pol i cy eval uat i on' s appr oach is

i nst r ument al or positivistic: val ue speci fi cat i on is t aken as ar bi t r ar y and ext r aneous.

In Dr or ' s terms, policy sciences shoul d cont r i but e t o "t he maki ng of policies which

achi eve mor e of goals det er mi ned by t he legitimate pol i cymaker s" ( Dr or , 197 l b, p.

138) [7]. Pol i cy analysis coul d t hen be used f or good or evil, as its techniques woul d be

val ue neut ral .

Thi s is fine if t here is an obvi ousl y legitimate val ue j udge, or , failing t hat , consensus

over values. In pract i ce, t hough, decent ral i zed political systems experi ence ext r eme

di ffi cul t y in maki ng up t hei r mi nds what t he goal s of pol i cy are. Wi t hi n a pl ural i st i c

political ar ena it is possible t o reach agr eement on an act i on wi t hout agr eement on t he

reasons for it, if values conflict (see Ei ndbl om and Cohen, 1979).

Success cri t eri a must be devel oped somehow; one al t ernat i ve is to base t hem on the

values of the client. However , put t i ng analysis to the service of an ar bi t r ar i l y chosen

client makes it accomodat i ng r at her t han critical with respect t o existing policy

pract i ce; it rei nforces t he status quo by wor ki ng within limits set by the existing

di st r i but i on of decision maki ng capabilities and the policy agenda as det ermi ned by

t he powers t hat be. Pol i cy analysis is ar guabl y necessary because all is not well.

A way of ci r cumvent i ng the probl ems policy eval uat i on has with value identifica-

t i on is t hr ough appeal t o legislative i nt ent (in t hose cases where rel evant legislation

does exist). However , legislative consensus may be achi eved and legislation passed

onl y if goals and values remai n undefi ned (Rei n and White, 1977), or at best stated in

t erms so vague as t o be meaningless. Thus, court s t end to find themselves in the

business of maki ng legislative i nt ent concret e. As an al t ernat i ve, an aut ops y can be

per f or med on the body politic, and t he past out comes of the political system exami ned

f or implicit goals and value premises. This may t ur n up some unsavor y results [8].

Fi scher (1980) at t empt s t o ext end the ability of policy eval uat i on to cope with

mul t i pl e confl i ct i ng values; his proj ect is t o suppl ement the model with a non- ar bi t r ar y

and convi nci ng means of maki ng value j udgment s. Fischer' s suggested appr oach is to

subject values t o val i dat i on accor di ng t o t hei r phenomenol ogi cal consi st ency with a

system of values; and, at a hi gher level still, with t he values of the political cul t ure of

society. In this process Fi scher leaves behi nd t he i nst rument al , social engi neeri ng

315

i mage of anal ysi s and deci si on in a manner consi st ent wi t h the her meneut i c model .

Thi s assessment of t he pol i cy eval uat i on model has deal t wi t h the ideal type. Wi t hi n

the br oa de r cont ext of this model , one does find wor k t hat is or can be critical of

exi st i ng pol i cy pract i ce. Thi s can be done by the pol i cy anal yst act i ng as his or her own

"cl i ent ", as an act or r at her t han an advi sor , hence capabl e of choosi ng val ues to gui de

the anal ysi s and the al t er nat i ves to be addressed. A good exampl e here is Ti t muss

(1974) on al t er nat i ve syst ems f or the medi cal suppl y of human bl ood. But adopt i ng

this st r at egy hi ghl i ght s the ot her fl aw in the model : j ust what val ues shoul d i nf or m the

anal ysi s? Why shoul d anal ysi s based on these be at all per suasi ve to anyone ot her t han

the anal yst ? Cont ext ual appr opr i at enes s is in danger t oo.

Pol i cy eval uat i on is an a ppr opr i a t e mode of pol i cy anal ysi s when t here exi st s a

single, i dent i fi abl e, l egi t i mat e pol i cy- maki ng body wi t h the capaci t y t o effectively

i mpl ement its decisions; furt her, t here is consensus whi ch ext ends t o bot h defi ni t i on of

the pol i cy pr obl e m at hand and t he cri t eri a f or j udgi ng pol i cy success. One may expect

these condi t i ons to be a ppr oxi ma t e d in a limited r ange of cases where the choi ce of

means t o an agreed upon end is the sole issue. Exampl es of such t echni cal issues

include quest i ons of i nf r ast r uct ur e const r uct i on, muni ci pal service delivery, choi ce of

al t er nat i ve weapons syst ems f or nat i onal securi t y, or even t he det er mi nat i on of t he

best way to reach the moon. The model runs i nt o t r oubl e when it is ext ended out si de

this r eal m to messi er ar eas such as t he eval uat i on of social pr ogr ams . Thi s per haps

expl ai ns why we are abl e to r each t he moon, yet unabl e to sol ve the pr obl ems of t he

ghet t o (Nelson, 1977).

Mode l Two: Advoc ac y

The advocacy a ppr oa c h t o pol i cy anal ysi s is an at t empt to come to grips wi t h the

di sj oi nt ed and i nt eract i ve nat ur e of pol i cy processes. It eschews the soci al engi neer i ng

i mage of the pol i cy eval uat i on model , and recogni zes t he limited capaci t y of any

pol i cymaker to behave in a r at i onal , pur posi ve, and effect i ve manner . Essent i al l y, the

advocacy model prescri bes t hat the pol i cy anal yst identifies with the st rat egi c posi t i on

of an act or wi t hi n t he pol i cy ar ena, he it an agency, l egi sl at or, or pr i vat e i nt erest , while

not necessari l y bei ng in s ympa t hy with t hat act or ' s values. Values become subor di nat e

to st r at egy or interest. Thi s is not as oppor t uni st i c as it sounds; an anal yst coul d choose

who t o wor k f or by t hei r affi ni t y to his or her val ue posi t i on.

The steps in a piece of advocacy research are t herefore:

(i) Choose a client;

(ii) Est abl i sh t he st rat egi c i nt erest of t hat client;

(iii) I dent i f y the pol i cy opt i on(s) t hat best serve(s) this st rat egi c interest;

(iv) Seek evi dence and ar gument s in s uppor t of the opt i on(s) identified.

Act or s in real wor l d pol i cy pr ocesses t ypi cal l y devot e mos t of t hei r t i me and ener gy

316

to st rat egy, or at t empt i ng to bend out comes to what t hey consi der desi rabl e, as

oppos ed t o c ont e mpl a t i on of the et hi cal basi s or goal s of t hat st rat egy. The rol e of the

anal yst becomes anal ogous t o t hat of a lawyer: t o bui l d a case f or t he cl i ent ' s posi t i on,

and selectively mar s hal facts, statistics, and ar gument s t o this end. It shoul d be not ed

t hat the fact t hat a piece of anal ysi s addresses mor e t han one al t ernat i ve does not mean

it is not advocacy; opt i ons may be i nt r oduced as st r awmen.

A good exampl e of the advocacy style of research based on a view of " cons umer

i nt erest " is t he t ype of wor k engaged in by " Nader ' s Rai der s", which t ypi cal l y com-

bines el ement s of i nvest i gat i ve j our nal i s m and legal met hodol ogy in bui l di ng a case

(see Siegel and Dot y, 1979 f or a case study). Much of what passes f or "fut ures

r esear ch" al so fits i nt o this cat egory.

I f one t akes t he pl ural i st vi ew t hat pol i cy out comes are det er mi ned by the i nt er ac-

t i on of compet i ng i nt erest s, t hen advocacy r esear ch has a posi t i ve f unct i on i nas-

mt i ch as it raises the level of di al ogue wi t hi n the pol i t i cal arena. It is also one sol ut i on

to t he pr obl e m of confl i ct i ng val ues. I n any si t uat i on t here ar e likely to be a numbe r of

l egi t i mat e t hough cont r adi ct or y val ue posi t i ons. Li beral s see val ue confl i ct as i nevi t a-

ble, gi ven t hat ends are and shoul d be i ndi vi dual (see, f or exampl e, Unger, 1975,

pp. 76-77).

Wi t hi n t he pl ural i st ar ena, all i nt erest s coul d empl oy t hei r own anal yst s t o st reng-

t hen t hei r cases, and t hei r opponent s woul d have t o pr oduce anal ysi s t o count er; in

exact l y t he same way t hat l awyers mus t r espond to t he ar gument s of t hei r pr ot agoni st s

in a court . Thi s is what Rivlin (1973) has in mi nd in pr opos i ng "f or ensi c soci al science"

as a model f or pol i cy anal ysi s. Under pl ural i sm, it is t he relative st rengt hs of t h e

r esour ces br ought t o bear by compet i ng i nt erest s t hat det er mi ne pol i cy out comes. Yet

a good a r gume nt is one ki nd of pol i t i cal resource, especi al l y i mpor t ant to fi nanci al l y

weak i nt erest s ( unf or t unat el y, a bad but persuasi ve ar gument can be a resource t oo).

Thus t he advocacy model does al l ow f or some i nj ect i on of r eason i nt o t he pol i cy

process. It meet s the cont ext ual i t y r equi r ement in its consi st ency wi t h the way deci si on

processes act ual l y wor k. Mor eover , advocacy is pr obl em- or i ent ed in t hat it is mot i vat -

ed by t he real concer ns of pol i cy st akehol der s. I t pr ovi des f or r esear ch t hat is c ommu-

ni cabl e, not onl y t o t he "cl i ent " it is done for, but al so t o ot her i nt erest s wi t hi n t he pol i cy

ar ena, as in l arge measur e it must r espond t o t hei r ar gument s.

However , t he anal yst adopt i ng this st r at egy does so at a mor al and i nt el l ect ual cost.

One r eason why pol i cy anal ysi s is soci al l y desi rabl e is t hat pol i t i cal processes left t o

t hei r own devices are capabl e of pr oduci ng out comes t hat are ei t her mani f est l y bad by

any cri t eri a or syst emat i cal l y bi ased t o power f ul interests. Pl ur al i sm emphasi zes

par t i al as oppos ed t o general interests; t here is no "i nvi si bl e hand" in politics t o ensure

t hat the i nt er act i on of t hese par t i al i nt erest s pr oduces accept abl e out comes at the

macr o level [9]. Pl ural i st i c syst ems exper i ence ext r eme di ffi cul t y in movi ng to any

coher ent al t er nat i ve f ut ur e when t he st at us quo is mani f est l y bad as, f or exampl e, in

the case of U. S. energy pol i cy in the l at e 1970s and earl y 1980s [10].

Advocacy' s mai n failing is its i nabi l i t y t o i dent i fy change in a posi t i ve di rect i on; ' i t s

317

bias is static and conservat i ve. The advocacy model casts t he pol i cy anal yst in the role

of an oper at i ng official r at her t han a critic of exi st i ng pract i ce or a source of ideas. It is

perhaps adequat e ( or inevitable) f or t he anal yst hired by an agency, legislator, or ot her

interest - and, indeed, conduci ve to career success. Much real worl d policy analysis

undoubt edl y falls i nt o this cat egory. Yet it will not facilitate the i dent i fi cat i on of

courses of act i on desirable on ethical gr ounds more persuasive t han the sum of

compet i ng interests. Not all values have r epr esent at i on within pol i cy processes; and

such r epr esent at i on as exists is highly skewed. Int erest s systematically excl uded or

under r epr esent ed include the poor , the unorgani zed, and fut ure generat i ons.

Advocacy is perhaps appr opr i at e in decision processes charact eri zed by multiple

act ors and confl i ct i ng values - it scores over pol i cy eval uat i on in this respect - but onl y

if these processes are al r eady pr oduci ng t ol erabl y good out comes. At its best, advo-

cacy seeks honest persuasi on, on behal f of a mor al posi t i on, r at her t han t he nar r ow

self-interest of an act or. Nader-st yl e "publ i c i nt erest " research woul d see itself in this

light. Advocacy does have a l egi t i mat e role in t he real worl d of politics. However, its

t hrust is to cajole r at her t han t o cont empl at e. It is a legitimate publ i ci t y device onl y if

t he anal yt i cal gr oundwor k has al r eady been done. All t oo oft en this prerequi si t e is

lacking, and advocat es end up by persuadi ng onl y themselves, or possibly deceiving

others.

Model Three: Single Framework

By a single f r amewor k appr oach to pol i cy analysis I mean the appl i cat i on to a pol i cy

pr obl em of an anal yt i cal f r amewor k devel oped i ndependent of t he pr obl em at hand,

nor mal l y by some academi c discipline or t radi t i on. Such f r amewor ks t her ef or e in-

cl ude welfare economi cs, cybernetics, soci ol ogy and ecology. The concl usi ons of

analysis are backed by t he met hod of t hei r pr oduct i on, itself gr ounded in an anal yt i cal

f r amewor k. Most pol i cy analysis done by academi cs falls i nt o this cat egory. Thus the

anal yst appr oaches the pr obl em at hand ar med with a set of t ool s and - equal l y

i mpor t ant - a cri t eri on or set of criteria f or pol i cy success inherent in the analytical

f ramework. In welfare economi cs, this value is allocative efficiency; in cybernetics, low

ent r opy of i nf or mat i on (Wiener, 1948); in the social st ruct ural appr oach, it can ei t her

be social or der (in the funct i onal i st vari ant ) or the interests of the undercl ass (in a

Mar xi st appr oach) ; in ecology, ecological bal ance ( Commoner , 1971). Beyond this, a

di sci pl i nary mat r i x can yield a pr edi sposi t i on to cert ai n kinds of pol i cy i nst rument s.

For exampl e, economi st s t end to t hi nk in t erms of mar ket or quasi - mar ket strategies

such as the negative i ncome t ax, voucher systems in educat i on, and charges r at her

t han regul at i on as the appr opr i at e pol i cy i nst r ument f or pol l ut i on cont rol . Cyber net -

ics l ooks f or sol ut i ons in or gani zat i onal design, while law (as a discipline) stresses

changes in the st ruct ure of legal rights. Each single f r amewor k can t her ef or e const i t ut e

a closed system of values, pol i cy al t ernat i ves, and met hods and t echni ques f or det er-

mining the effects of al t ernat i ves on values.

318

The procedures f or policy analysis in the single f r amewor k mode are therefore:

(i) Become educat ed in a social science discipline; assimilate its norms, met hods, and

techniques;

(ii) Assimilate the range of pol i cy i nst rument s i nherent in the f r amewor k;

(iii) When faced with a policy pr obl em, i nt er pr et it in the light of this anal yt i cal

f r amewor k;

(iv) Det er mi ne how t he f r amewor k' s preferred pol i cy i nst rument (s) can be appl i ed t o

the case at hand.

Obvi ousl y at risk here are cont ext ual i t y and pr obl em- or i ent at i on. Ther e is no

guar ant ee t hat analysis will t ake i nt o account the reality of the di st ri but i on of capabili-

ties wi t hi n the decision process, or t hat policy st akehol ders will share the analyst' s

defi ni t i on of the probl em. On what gr ounds beyond the di sci pl i nary t rai ni ng of the

anal yst . shoul d one f r amewor k be chosen, and ot her possibilities excl uded? Why

shoul d the chosen f r amewor k be at all persuasi ve t o policy pract i t i oners, and per-

ceived as relevant? For exampl e, a piece of policy analysis t hat identifies the most

efficient (in the economi c sense) st rat egy f or t he leasing of federal lands f or fossil fuel

pr oduct i on may be of little concer n to peopl e in the Depar t ment of the I nt er i or (the

responsi bl e management agency) t ryi ng to bal ance compet i ng interests such as the oil

i ndust ry, state and local government s, and envi ronment al i st s in the const r uct i on of a

lease sale schedule. One ends up with analysis t hat is inspired by one value among

many, bl i nkered by the discipline of the analyst.

Wi t h these reservat i ons, analysis in this mode is undoubt edl y capabl e of i dent i fyi ng

Changes in a positive di rect i on. The single f r amewor k mode is appr opr i at e when t here

exists a consensus among st akehol ders on values, or at least on the range of values t hat

mat t er, which is itself congr uent with the nor mat i ve posi t i on embedded in t he anal yt i -

cal f r amewor k. Analysis in this image can be especially useful when, given these

condi t i ons, it is uncl ear to the non-speci al i st which of a number of al t ernat i ves shoul d

be f avor ed; or even what the set of al t ernat i ves is. One of the best exampl es here is

macr oeconomi c pol i cy analysis, di rect ed at cri t eri on variables such as i nfl at i on,

unempl oyment , and i nt erest rates. Here, of course, t he consensus is on the range of

values t hat mat t er, as opposed to t hei r weighting.

When the above ci rcumst ances obt ai n, analysis in t he single f r amewor k mode can

provi de gr eat er scope t han policy eval uat i on or advocacy f or creativity in the devel-

opment of policy al t ernat i ves. Unf or t unat el y, these ci rcumst ances are sufficiently rare

t o make exampl es of i nappr opr i at e si ngl e-framework analysis all t oo numerous.

Mi cr oeconomi cs al one has given us PPBS, Britain' s Roskill Commi ssi on on ai r por t

siting, and monet ar y val uat i ons of intangibles t hat can verge on the ludicrous.

Mo de l Four: Soci al Choi ce

The social choi ce model of policy analysis takes as its units of analysis the mechani sms

3t 9

for pr oduci ng collective choices, r at her t han public policies per se. Such mechani sms

i ncl ude regimes, hierarchies, vot i ng systems, bargai ni ng, market s, and ar med conflict.

This model can t her ef or e cor r ect one maj or defect of t he pol i cy eval uat i on model: i t

does not requi re t hat any act or be able to f or mul at e and i mpl ement public pol i cy in

any r at i onal and purposi ve fashi on. Rat her, it conceives of act ors - i ncl udi ng t hose

with nomi nal cont r ol over the maki ng of policy - as operat i ng within an ar ena whose

basic f r amewor k consists of a social choi ce mechani sm. Act ors may oper at e rat i onal l y

(in t erms of the calculus of self-interest) within this arena [11], but none possesses the

capaci t y to effect social engineering. Social choice mechani sms are not neut ral in

t erms of t he kinds of out comes t hey pr oduce, hence t hey can be j udged by per f or mance

criteria. For exampl e, economi st s have t r adi t i onal l y j udged the superi ori t y of market s

over cent ral l y pl anned. st ruct ures by t hei r abi l i t y to satisfy i ndi vi dual preferences (see,

for exampl e, Prybyl a, 1969).

The i nj unct i ons of the appr oach bear a great deal of si mi l ari t y t o t hose of pol i cy

eval uat i on:

(i) Speci fy the criteria accor di ng to which i nst i t ut i onal per f or mance is to be j udged;

(ii) I dent i f y a set of al t ernat i ve social choi ce mechani sms, i ncl udi ng the status quo;

(iii) Det ermi ne how well each al t ernat i ve per f or ms accor di ng to each criterion;

(iv) Advocat e a t ransi t i on to the mechani sm t hat scores best accordi ng to some

weighted sum of the criteria.

Thi s ki nd of appr oach has f ound its greatest appl i cat i on to dat e at t he i nt er nat i onal

level, an exempl ar y decent ral i zed deci si on system. It also lends itself well to the

analysis and assessment of regimes f or the management of nat ural resources (see

Young, 1977, 1982), especially when decision maki ng capabilities are dispersed and an

overal l aut hor i t y f or decisions is missing. Thus one can speak of a r egul at or y regime

f or pol l ut i on cont r ol , a c ommon pr oper t y regime f or ocean fisheries, a public pr oper t y

regi me f or forests, and a compet i t i ve leasing regime f or oil and gas ext r act i on. A

regime is t her ef or e a col l ect i on of i nst i t ut i onal ar r angement s t hat pr ovi de a set of

incentives and an arena, within which act ors operat e, which will i ncor por at e rights,

rules, regulations, and compl i ance mechani sms (Young, 1982).

Analysis wi t hi n t he social choi ce image is not tied t o an analyst-client rel at i onshi p,

for, obvi ousl y, no act or is capabl e of social engi neeri ng to the ext ent of regime

mani pul at i on. Inst ead, t he anal yst takes a step back f r om the f r ay of the pol i cy

process; at best, analysis will feed i nt o debat es over the i ncr ement al t r ansf or mat i on of

regimes (see Young, 1977, pp. 235-236). Of course, the case f or full-scale regime

const r uct i on does occasi onal l y arise; an obvi ous exampl e at t he i nt er nat i onal level is

the U.N. Conf er ence on the Law of the Sea, an at t empt to const r uct a management

regime f or the oceans.

The social choi ce mode suffers few illusions concerni ng the ability of pol i cymakers

t o under t ake social engineering. In addressi ng t he cont ext of pol i cy choice, it aut omat -

320

ically achi eves cont ext -sensi t i vi t y. It can achi eve rel evance t o the concer ns of st ake-

hol der s if t her e is a met apol i cy process in act i on; t hat is, if regi me change is on t he

agenda. Mor eover , the mode pr ovi des f or i nnovat i on in the desi gn of al t er nat i ve

regi mes. However , it does have its defects: mos t f undament al l y, its choi ce of success

cri t eri a f or social choi ce mechani sms is essent i al l y ar bi t r ar y. Pol i cy eval uat i on deals

wi t h t he cri t eri a pr obl e m t hr ough appeal t o s ome val ue j udge ext r aneous t o the

anal ysi s, and t he single f r a me wor k model appl i es val ues i nherent in anal yt i cal f r ame-

wor ks. Soci al choi ce l acks recourse t o ei t her of these al t ernat i ves. I n t aki ng t he syst em

as the uni t of anal ysi s, t here is no case f or appl yi ng cri t eri a t o its per f or mance based on

the val ues of any act or wi t hi n t hat syst em. No val ues are i nherent in t he soci al choi ce

anal yt i cal f r amewor k; cri t eri a such as al l ocat i ve efficiency, di st ri but i ve equi t y, social

order, l ow ent r opy, and pol i t i cal feasi bi l i t y coul d all be br ought to bear.

Ther e are al so t wo ki nds of issues t hat t he soci al choi ce model does not address very

well, l arge and smal l quest i ons respect i vel y. The a ppr oa c h may be silent on the ki nd of

f ut ur e a soci al choi ce mechani s m is t aki ng us into: it coul d tell us ( accor di ng t o some

cri t eri a) what ki nd of r egi me mi ght be desi r abl e f or t he ma na ge me nt of a nat ur al

resource such as shale oil, but little a bout whet her t hat oil shoul d be expl oi t ed at all.

And soci al choi ce is of little hel p f or smal l er quest i ons of pol i cy choice, such as

whet her t o hol d an oil lease sale in ar ea x in year y. The model is t hus mos t appl i cabl e

t o mi ddl e range quest i ons of i nst i t ut i onal ar r angement s.

The soci al choi ce mode of anal ysi s is appr opr i at e, t hen, when t here is a met apol i cy

process under way; f ur t her , t here must be some consensus on values, whi ch the anal yst

shares. Agai n, this ki nd of anal ysi s can be especi al l y useful in cl ari fyi ng the opt i ons if

st akehol der s st art out wi t h no cl ear i dea of t he ki nd of regi me or social choi ce

mechani s m t hey want . Soci al choi ce anal ysi s has a niche, but it is not t oo ext ensi ve.

Model Five: Moral Phi l osophy

An et hi cal a r gume nt or line of r easoni ng is one whi ch deri ves i mpl i cat i ons f or

i ndi vi dual or soci al pr act i ce f r om some basi c mor al pri nci pl e. Exampl es of the

appl i cat i on of mor al phi l os ophy t o publ i c pol i cy include di scount i ng the f ut ur e (see

Si kor a and Barry, 1978), man' s obl i gat i on t o nat ur e (see Tr i be, 1976), and human

ri ght s in publ i c pol i cy (see Br own and MacLean, 1979). Et hi cal ar gument s need not be

conf i ned t o goal s or desi red st at es as st ar t i ng poi nt s and end poi nt s; const r ai nt s upon

act i on can ent er i nt o the a r gume nt t oo. Thus bot h ends- based and means - bas ed

ar gument s ar e possi bl e. An exampl e of ends- based r easoni ng is the const r uct i on of a

soci et y accor di ng t o pri nci pl es of j ust i ce (Rawl s, 1971); f or a means- based ar gument ,

see how scarce r esour ces shoul d be di st r i but ed in an over popul at ed worl d ( Har di n,

1972).

Pol i cy anal ysi s can be appr oached in this manner ; t he steps woul d be:

321

(i) Ident i fy a mor al f r amewor k;

(ii) I nt er pr et the pol i cy pr obl em at hand in the light of this f r amewor k;

(iii) Devel op a set of pri nci pl es f or the conduct of public pol i cy in this pr obl em area.

Primafacie, this woul d seem t o solve t he pr obl em of val ue choi ce in pol i cy analysis

at a s t r oke - leave it to mor al phi l osophers. And indeed, phi l osophers have of late been

payi ng gr eat er at t ent i on t o publ i c pol i cy issues, as a perusal of j our nal s such as Ethics,

Philosophy and Public AJfairs, and Environmental Ethics will attest.

Still, one does not find pol i cymakers beat i ng a pat h to the door s of phi l osophers,

begging f or mor al gui dance and f or good reason: mor al phi l osophy as such lacks any

means f or t he empi ri cal i dent i f i cat i on of courses of act i on. Mor al phi l osophy must of

course have some mi ni mal empi ri cal cont ent ; ethical st at ement s do not exist in a

vacuum, i ndependent of t he nat ur e of the worl d t o which t hey are i nt ended to apply.

And it is possible t o cite exampl es of empi ri cal l y wel l -grounded and pol i cy-di rect ed

mor al phi l osophy ( Br own and MacLean, 1979; Goodi n, 1980). But phi l osophers,

especially when writing f or publ i cat i on, oft en t end to choose empi ri cal cases accordi ng

to how well t hey illustrate as ar gument , avoi di ng fact ual compl i cat i on wherever

possible. The upshot of this is t hat , however much one mi ght wish pol i cymakers to

spare a t hought f or mor al choice ( MacRae, 1976), this will oft en be unrealistic.

Analysis may fail accor di ng to the pr obl em- or i ent at i on cri t eri on t hr ough an inability

to make the connect i on to the concer ns of st akehol ders unused to t hi nki ng in t erms of

mor al abst ract i ons.

Though mor al phi l osophy is rarel y sufficient in itself as a model f or pol i cy analysis,

it is hard t o concei ve of any si t uat i on of pol i cy choi ce beyond the nar r owl y technical to

which it has no rel evance at all. Ethics can al ways gener at e br oad principles f or social

practice. This relevance will be especially great in si t uat i ons when pol i cy debat e is over

the ends r at her t han the means of policy, f or exampl e, abor t i on, human rights, and

ot her so-called "mor al " issues. An exami nat i on of ethics j our nal s will reveal t he ext ent

to which philosoph.ers t arget this kind of issue. The appropri at eness of mor al philo-

sophy as pol i cy analysis is enhanced when act ors have a genui ne concer n f or the mor al

issue i nvol ved, and yet are sufficiently unsure of t hei r own posi t i ons to be willing to

listen t o what t he phi l osopher has to offer. Needless to say, t he strategic interests of

act ors will oft en get in t he way.

III. He r me n e u t i c s

Each of the five modes of pol i cy analysis addressed so f ar has its uses, but each is

appr opr i at e onl y in a specific set of condi t i ons. M oreover, aft er summi ng t he capabili-

ties of all five models, we are still left with a residual cat egor y of ci rcumst ances in

which none of these modes of analysis is appr opr i at e. This residual set is defined by a

pl ural i st i c deci si on process made up of a mul t i pl i ci t y of act ors and interests which is

not pr oduci ng mani fest l y good out comes. Wi t hi n this process, confl i ct i ng and uncer-

322

t ai n values are the norm; typically, t here will be little consensus on pr obl em defi ni t i on,

and no well-defined policy agenda. In short , this cat egory cont ai ns the "messy" cases.

The residual set may be large or small, dependi ng on one' s view of the efficacy of

pluralistic deci si on processes. What is undeni abl e, t hough, is t hat it is composed of the

most pr obl emat i c kinds of cases where t he need and demand f or analysis is greatest. It

woul d i ndeed be unf or t unat e if pol i cy analysis as a discipline possessed sophi st i cat ed

means f or deal i ng with simple cases while lacking t he power to tackle the most

i mpor t ant ones.

The i nabi l i t y of model s 1-5 to cope with this messy set stems in large measure f r om

t hei r ineffectiveness in securing phenomenol ogi cal relevance. Phenomenol ogi cal

met hods are al r eady ext ant in empi ri cal social research (for exampl e, Schuman, 1982;

see also Bernst ei n 1976, p. xvii); shoul d not pol i cy analysis simply adopt these? Unf or -

t unat el y, phenomenol ogy' s spirit is descriptive r at her t han evaluative; it seeks onl y t o

reconst ruct life si t uat i ons (Bernst ei n, 1976, pp. 167-169). Phenomenol ogy shares with

behavi or al social science a view of the social scientist as a passive, disinterested

observer. No al l owance is made f or this obser ver t o cont r i but e any expert i se at all to

t he si t uat i on bei ng anal ysed. Phenomenol ogy is t her ef or e i ncapabl e of i dent i fyi ng

posi t i ve changes; it is i nappl i cabl e as a model f or pol i cy analysis. It can, however, pl ay

an anci l l ary rol e in pol i cy research by giving us an under st andi ng of how social real i t y

l ooks t o t he i ndi vi dual s affect ed by a policy, f r om which criteria f or eval uat i on may be

established or conf i r med (Fischer, 1980, p. 141). In addi t i on, it may give us an idea of

what ki nds of policies - especially social policies will not wor k in a given si t uat i on.

This kind of analysis lies at the r oot of Banfield' s (1970) pessimism concerni ng the

possibility of effective ant i - pover t y policy.

Phenomenol ogy leaves us in a relativistic abyss when it comes t o t he i dent i fi cat i on

of posi t i ve change. Thus we t ur n t o hermeneut i cs. Her meneut i es shares the phenome-

nologist' s cri t i que of behavi oral social science, but differs f r om phenomenol ogy in t hat

it is a creat i ve and eval uat i ve activity. Her meneut i c policy analysis may be defi ned as

the eval uat i on of existing condi t i ons and the expl or at i on of al t ernat i ves to t hem, in

t erms of cri t eri a deri ved f r om an under st andi ng of possible bet t er condi t i ons, t hr ough

an i nt erchange bet ween the frames of reference of analysts and act ors [ 12].

The i mpl i cat i on is t hat t he policy anal yst shoul d seek a medi at i on (or conf r ont at i on)

bet ween pol i cy pract i ce and the frames of reference or t aci t social t heori es of act ors

within the pol i cy process, on the one hand, and t he anal yt i cal f r amewor ks he has at his

fi ngert i ps as a social scientist on the ot her. Thi s takes place in a manner anal ogous t o a

conver sat i on in whi ch t he hor i zons of bot h part i ci pant s are ext ended t hr ough con-

f r ont at i on with one anot her (see Gadamer , 1975). The result of this ki nd of dialectic

shoul d i deal l y be a synt hesi s of t he best of bot h ki nds of f r amewor k, r at her t han

i mperi al i sm of the anal yt i cal f r amewor k (as implied by t he single f r amewor k model )

or t he act or' s f r amewor k (as in advocacy and, to a lesser ext ent , policy eval uat i on).

To use t he t er mi nol ogy of t he Fr ankf ur t School of critical t heor y, pol i cy analysis is

surely an " emanci pat or y" discipline par excel l ence. An emanci pat or y cognitive inter-

323

est is one t hat strives t o i mpr ove human exi st ence t hr ough raising the consci ousness of

t hose whom social scientific laws - "i deol ogi cal l y f r ozen rel at i ons of dependence"

( Haber mas, 1971, p. 310) - are about [ 13]. Psychoanal ysi s is t he model emanci pat or y

discipline: i ndi vi dual s are conf r ont ed with knowl edge and forced i nt o self-reflection.

Psychoanal ysi s utilizes her meneut i c under st andi ng (in a search f or t he meani ng of

verbal i zat i ons) and "t echni cal " expl anat i on of the causes of suppressi on of experi ence,

but these are united and dri ven by an emanci pat or y impulse t hat seeks to free the

pat i ent f r om forces out si de his or her consci ous cont r ol (Gi ddens, 1976, p. 60) [14].

This is an especially appr opr i at e anal ogy f or policy analysis t hat is driven by a desire

f or real i t y i mpr ovement , t hat must be cont ext ual , and which possesses sets of i nst ru-

ment al t echni ques f or det ermi ni ng cause and effect rel at i onshi ps (for exampl e, the

per f or mance of pol i cy alternatives accor di ng to some st andard) [15].

In this light, a piece of pol i cy analysis shoul d ai m f or a dialectic bet ween policy

anal yst s and act ors. Ethics and values shoul d be an i nt egral part of this, not t aken as

given, but amenabl e to reasoni ng and subject to adj ust ment as a result of discourse (see

Fischer, 1980). A pol i cy pr obl em pr obl em or di l emma in fact provi des an ideal cont ext

f or reflection on collective moral s and values, which one woul d expect to be in a state

of fl ux r at her t han static or pr edet er mi ned. As Wi l davsky (1979a, pp. 41-61) recog-

nizes, objectives are fluid, and are onl y devel oped in the worki ng out of a pol i cy or

pr ogr am (he refers to a"s t r at egi c r et r eat on objectives"). Even mor al phi l osopher s do

not posit t hat moral principles be absol ut e; instead, these principles can st and in a

"reflective equi l i bri um" with real world experi ence and i nt ui t i ons ( RaMs, 1951).

The her meneut i c image is of di scourse and dialectic r at her t han i nst rument al ,

pur posi ve act i on; yet i nst r ument al knowl edge - t he subst ance of the policy eval uat i on

model - is necessary to generat e pol i cy ideas as par t of t hat discourse. This is where the

di sci pl i nary f r amewor ks of social scientists can come i nt o play. The anal yst must

at t empt t o achi eve an under st andi ng of the pract i cal probl ems and frames of reference

of act ors and pol i cymakers, while si mul t aneousl y remai ni ng capabl e of criticism of the

practices in which these act ors are engaged [16J. Effective di scourse implies t hat t he

anal yst has somet hi ng to bri ng t o these probl ems.

To make this specific, I woul d suggest t hat policy analysis in the hermeneut i c mol d

cont ai n the f ol l owi ng el ement s. Ther e shoul d be t wo st art i ng points: on the one hand,

ethics and nor mat i ve t heory, and on the ot her the appar ent nor mat i ve basis of the

status quo in t he decision process - t hat is, the values and interests represent ed in the

existing regime and policy process. In the case of social policy, these shoul d also

i ncl ude t he values t hat are const i t ut i ve of t he social si t uat i on mor e generally. The

anal yst shoul d engi neer a conf r ont at i on bet ween et hi cal f r amewor ks and t he effective

val uat i ve basis of exi st i ng pract i ce by assessing this status q u o in t erms of these

f r amewor ks. Thus t here will be an el ement of advocacy in the analysis, but it is

advocacy of mor al posi t i ons r at her t han the strategic interest of any act or [17]. Any

et hi cal posi t i ons arri ved at can t hen be used t o det er mi ne the f r amewor ks most appr o-

pri at e f or t he i nst r ument al or pol i cy eval uat i on par t of t he analysis. These f r amewor ks

324

can be one, or, given a mul t i pl i ci t y of ethical f r amewor ks, mor e t han one of the

appr oaches referred t o under t he single f r amewor k model. All the available frames of

reference are highly i ncompl et e f or public pol i cy analysis; this makes mul t i - met hod

i nqui r y highly desirable. Thi s is not a pr escr i pt i on f or met hodol ogi cal anarchi sm; but

t here is no need t o set up par adi gms and j udge bet ween t hem - as a post - Kuhni an view

of t he progress of scientific disciplines mi ght suggest - and a single best f r amewor k

chosen. A ful l er under st andi ng may be achi eved by several "cut s" at real i t y (Durrel l ,

1957 et seq; Allison, 1971), because no one par adi gm can descri be t he wor l d in a com-

prehensi ve way.

Beyond this, it shoul d be recogni zed t hat all cases are di fferent , hence likely to

requi re analysis t hat differs in its details. As Wi l davsky (1979a) points out, policy

anal ysi s is an " ar t " and a "cr af t " r at her t han t he unt hi nki ng appl i cat i on of a set of

t echni ques. Cont ext ual policy analysis must obvi ousl y vary accordi ng t o the cont ext .

Is it possible to poi nt t o any exempl ar y pieces of policy analysis in maj or accord with

the precept s of the her meneut i c model ? One piece of wor k which illustrates the

possibilities of t he appr oach is t he analysis under t aken by Canada' s MacKenzi e Valley

Pipeline I nqui r y bet ween 1974 and 1977. Thi s commi ssi on was established under the

di rect i on of Mr. Just i ce Thomas R. Berger t o investigate the likely social, envi r onmen-

tal, and economi c i mpact s of the const r uct i on of pipelines to t r anspor t oil and gas

f r om t he Al askan and Canadi an Arct i c to mar ket s in Sout her n Canada and the

cont er mi nous Uni t ed States. Unlike many such commi ssi ons of i nqui ry, it did not

pr oceed with t he i nt ent i on of appl yi ng a veneer of concer n to decisions whose

out comes were in no doubt , nor did it merel y seek t o synthesize t he submissions of

expert s. Rat her , Berger initiated a process of i nt er act i on and communi cat i on bet ween

t he st aff of his i nqui ry, gover nment agencies, exper t witnesses (engineers, geologists,

ecologists, economi st s, ant hr opol ogi st s, and others), and organi zed and unorgani zed

interests such as the oil i ndust ry, native peoples, consumers, and envi ronment al i st s.

The fi nal r epor t of the i nqui r y was an out come of this di al ogue (see Berger, 1977),

t hough mor e i mpor t ant t han the cont ent of this r epor t (excellent t hough it is) was the

process set in mot i on, which had consi derabl e i mpl i cat i on f or the bal ance of compet -

i ng values, interests, and rights in the Canadi an Arctic.

Berger went beyond t he t echni cal submi ssi ons of expert s to address and r espond t o

pol i t i cal quest i ons. To avoi d maki ng t he i nqui ry "a f or um f or lawyers and exper t s"

(Berger, 1977, vol. II, p. 226), communi t y heari ngs were held in t owns and villages

t hr oughout Canada' s West ern Arctic region, and also in Canadi an provi nces out si de

t he Arctic. The idea of these heari ngs was to di ssemi nat e i nf or mat i on t o or di nar y

citizens, encour age the ar t i cul at i on of t hei r concerns, and also to i ncor por at e the

wi sdom t hat t hey had to offer (for exampl e, with respect to subsistence hunt i ng and

fishing in t he region). Represent at i ves of t he pipeline compani es at t ended these

meetings t o r espond t o concer ns expressed and to cont r i but e t echni cal expertise. The

I nqui r y pr ovi ded funds t o fi nanci al l y weak interests - native peoples, envi r onment al -

ists, Arct i c muni ci pal gover nment s , and Arct i c businesses - to enabl e t hem t o devel op

325

t hei r cases. In t erms of t he her meneut i c model , this enhanced the "communi cat i ve

compet ence" ( Haber mas, 1970) of these act ors.

The Berger i nqui r y t her ef or e pr ovi ded an ar ena f or i nt er act i on and di scourse

bet ween analysts and ot her act ors [ 18]. Its process exhi bi t ed several key feat ures of the

her meneut i c model . The val ue posi t i ons of the i nqui ry were not t aken as ar bi t r ar y or

pr edet er mi ned, but devel oped in i nt eract i ons among part i ci pant s. The i nqui ry worked

within t he const rai nt s of a pre-specified set of opt i ons (pert ai ni ng to the const r uct i on

or ot herwi se of t he pipelines), yet escaped these const rai nt s to devel op strategies f or

the economi c, cul t ural , and political devel opment of the Canadi an Nor t h [19]. Disci-

pl i nary f r amewor ks such as economi cs and ant hr opol gy were appl i ed in the cont ext of

the pr obl em at hand. A consci ous (and successful) at t empt was made to relate the

frames of reference of analysts and act ors. Mor al and ethical questions, especially with

respect t o the rights of i ndi genous peoples, were addressed. The i nqui ry was sensitive

t o political issues in the di st ri but i on of pol i cy-maki ng capabilities, poi nt i ng out t hat

some interests - especially t hose of i ndi genous peopl es - had been syst emat i cal l y

excl uded f r om t he pol i cy process. The Berger r epor t was successful in its "communi ca-

t i ve" t ask of bri ngi ng issues to the political agenda, and pr ovoked consi derabl e debat e

in Canada and beyond. Overall, t he Berger i nqui r y illustrates the pot ent i al f or effec-

tive policy analysis within the hermeneut i c mold. Its details might not be capabl e of

precise dupl i cat i on elsewhere, yet it indicates the range of the possible.

Fur t her feat ures of her meneut i c pol i cy analysis in act i on are illustrated (usually

i nadver t ent l y) by several cases of cont r over sy over social policy. The disputes over the

West i nghouse Head St ar t eval uat i on are a case in poi nt ; here, one f ound pol i cy

anal yst s debat i ng with one anot her and the st akehol ders in t he pr ogr am (see Williams

and Evans, 1972; Fischer, 1980, pp. 119-124). At issue were the t heoret i cal frame-

works of the analysts, the i nt er pr et at i on of results, the phenomenol ogi cal appr opr i -

ateness of eval uat i on criteria, the purposes of the pr ogr am, and even the poi nt of the

analysis itself, t hat is, whet her it shoul d uncover fai l ure or search f or success. The

Col eman r epor t on equal i t y of educat i onal oppor t uni t y i ni t i at ed a similar ki nd of

process.

Her meneut i c analysis is especially appr opr i at e f or br oad ai m social pr ogr ams (such

as Head St art ), f or which success cri t eri a are best devel oped in the cont ext of what the

t ar get popul at i on itself perceives and values; it is the compet ence of the t arget

popul at i on which is ( or shoul d be) t he issue. The appar ent fai l ure of many Gr eat

Soci et y pr ogr ams may be part i al l y expl ai ned on t he gr ounds t hat not hi ng appr oxi mat -

ing hermeneut i c analysis went i nt o t hei r f or mul at i on.

The her meneut i c mode of pol i cy analysis may be challenged on the grounds t hat to

be received as "r el evant ", the concept ual f r amewor k of the anal yst shoul d cor r espond

to t hat of t he "cl i ent " (see Meltsner, 1976; Wildavsky, 1979a). Appl yi ng by anal ogy the

rest ri ct i ons upon ways of seeing i mposed by a par adi gm in a scientific communi t y

( Kuhn, 1962), pol i cymakers may not be recept i ve to analysis t hat quest i ons t hei r

par adi gm of decision, and hence will t end to reject the analysis r at her t han the

326

par adi gm (see Li ndbl om and Cohen, 1979). But if we assess t he success of a piece of

analysis by its cont r i but i on t o raising the level of di scourse and changi ng climates of

opi ni on, we find a number of exempl ar y successes t hat are works which radi cal l y

chal l enge t he status quo, f or instance, Keynes (1936), Beveridge (1942), Myr dal (1944),

Jencks (1971), Ti t muss (1974), and Castells (1977). This adds force to the cont ent i on of

Weiss (1977) t hat decision makers oft en give consi derabl e weight to pieces of analysis

with i nnovat i ve i mpl i cat i ons, even if t hey are politically unaccept abl e with respect t o

t he deci si on at hand. Tr eat i ng the non- cor r espondence of concept ual f r amewor ks as

an i mmut abl e pr obl em makes any ki nd of pol i cy analysis of dubi ous pur pose, not j ust

her meneut i c analysis. Mor eover , as the exampl e of the Berger I nqui r y suggests, it is

possible t o over come barri ers t o communi cat i on.

To accept the utility of the her meneut i c model is not a r evol ut i onar y step. Indeed, in

some ways it is a r et ur n t o the "pol i cy sciences movement " of the post Wor l d War II

peri od ( Ler ner and Lasswell, 1951). As Dunn (1981, p. 19) points out, this movement

shared much in c ommon with t he effort s of t he Fr ankf ur t School t o establish a critical

social science: "t he ul t i mat e goal is the real i zat i on of human dignity in t heor y and fact "

(Lasswell, 1951, p. 15, quot ed in Dunn, 1981, p. 19).

IV. Conclusion

The her meneut i c model as out l i ned here is no panacea; it obvi ousl y requires a great

deal in t he way of creat i ve ef f or t t o make it work. The anal yst under pressure of time

wi t hi n a gover nment bur eaucr acy ma y be excused f or preferri ng policy eval uat i on or

advocacy. Conversel y, social scientists concer ned with anal yt i cal puri t y may be more

comf or t abl e with the single f r amewor k of t hei r discipline, social choice, or mor al

phi l osophy.

My cont ent i on is t hat , f or a wide range of " me s s y" si t uat i ons of pol i cy choice, the

her meneut i c mode of pol i cy analysis is the most appr opr i at e form. Hermeneut i cs

makes a f r ont al at t ack to achi eve the cri t eri a of cont ext ual i t y, pr obl em- or i ent at i on,

and a capaci t y t o i dent i fy positive changes. Each of model s 1-5 has its niche in which

these cri t eri a can be met. One can t hi nk of her meneut i cs as a ci rcui t ous but sure rout e.

t o a given dest i nat i on, expensi ve in t erms of the t i me and energy t hat must be devot ed

to it. Model s 1-5 offer short cut s to t he same dest i nat i on under the right ci rcumst ances;

but if the ci rcumst ances are not right, these short cut s t ur n out to be dead-ends.

Acknowledgments

I am grat eful f or the advice and encour agement of Or an Young, Davis Bobrow, Kat hy

Per of f , Sam Post bri ef, Virgil Nor t on, Rober t Goodi n, an anonymous referee, and the

edi t or of Pol i cy Sciences.

327

No t e s

l For an i nt el l ect ual hi s t or y of pol i cy anal ysi s f r om ear l y opt i mi s m to l at er mal ai se, see Nel son (1977).

2 In fact , p h e n o me n o l o g y gi ves us no f ool pr oof way of j udgi ng bet ween c ompe t i ng descr i pt i ons.

3 For a n e xpl or a t i on of t he l i nk bet ween p h e n o me n o l o g y and pol i cy anal ys i s in t he c ont e xt of t he

val i dat i on of cri t eri a f or pol i cy eval uat i on, see Fi scher (1980, 111-148).

4 Dr or (197 l a) pr opos e s a "pr ef er i s at i on" cr i t er i on f or pol i cy anal ysi s; a piece of anal ys i s s houl d be j udge d

by t he di f f er ence bet ween t he qual i t y of t he pol i cy as it is, havi ng ma d e use of t he anal ysi s, and t he qual i t y

of t he pol i cy as it woul d ot her wi se be.

5 Th o u g h , as Pr e s s ma n and Wi l davs ky (1973) de mons t r a t e , t echni cal pr obl e ms can bl ock t he i mpl e me n-

t at i on of pr ogr a ms even when all ma j or par t i ci pant s agr ee on basi c goal s.

6 Good e xa mpl e s woul d i ncl ude Knees e a nd Schul t ze (1975) on pol l ut i on cont r ol pol i cy, and Ti t mus s

(1974) on al t er nai i ve s ys t ems f or t he s uppl y of bl ood f or medi cal uses. See al so t he series of Ev a l u a t i o n

S t u d i e s R e v i e w A n n u a l s ( Cook et aL 1978).

7 In f ai r nes s t o Dr or , he does s peak of t he need for "val ue anal ys i s " at t he out set of any st udy, and wri t es

t hat pol i cy sci ences s houl d i ncor por at e " s ubs t a nt i ve mat er i al f r om appl i ed et hi cs and pol i t i cal phi l o-

s ophy, and a dva nc e d me t hodol ogi e s f or h a n d l i n g val ue i s s ues " ( Dr or , 1971a, p. 58). But he gi ves no

i ndi cat i on as t o what s uch me t hodol ogi e s s houl d l ook like.

8 Thi s ma y in f act be a usef ul f unc t i on f or pol i cy research: to expose i mpl i ci t val ues a nd t he mor al

f r a me wor k of choi ce. See Lowi et al. (1975) and Rei n (1976).

9 See Schel l i ng (1978) f or a di s c us s i on of how r e a s ona bl e i ndi vi dual be ha vi or can pr oduc e s t r ange

cons equences at t he ma c r o level.

10 See Lowi (1969) on t he gener al weaknes s es of pl ur al i sm.

11 I ndeed, t he t he or y of publ i c choi ce, whi ch of t en addr es s es i t sel f t o me c h a n i s ms f or ma ki ng collective

choi ces, a s s ume s t ha t i ndi vi dual s do behave r at i onal l y.

12 Wi t h o u t wi s hi ng t o get i nt o t he f i ner det ai l s of t he ma i n s chool s of t h o u g h t in c o n t e mp o r a r y h e r me n e u -

t i cs (see Bl ei cher, 1980 f or an a c c ount of t hese) , t he a p p r o a c h pr opos e d here is mor e cons i s t ent wi t h

cri t i cal he r me ne ut i c s ( as s oci at ed especi al l y wi t h Ha be r ma s ) - f or whi ch t he e ma nc i pa t or y i mpul s e is

cent r al - t h a n it is wi t h t he mor e pur el y i nt er pr et i ve he r me ne ut i c s as s oci at ed wi t h Ga da me r . Ha be r ma s ,

in c ont r a s t t o Ga da me r , r ecogni ses t ha t l a ngua ge in t he real wor l d can be s ys t emat i cal l y di st or t ed by

cont r ol l i ng "t echni cal " f act or s.

13 Ha b e r ma s i dent i fi es a c a de mi c di sci pl i nes wi t h knowl e dge - c ons t i t ut i ng i nt erest s. Th u s nat ur al sci ences

s houl d be i ns pi r ed by a " t echni cal " i nt erest , cul t ur al sci ences ( l i t er at ur e, hi st or y, a nt hr opol ogy) by a

her meneut i c i nt erest , and soci al sci ences by an e ma nc i pa t or y i nt erest .

14 Gi ddens and Ha b e r ma s bot h r ecogni ze t hat , in pract i ce, ps ychoanal ys i s exhi bi t s a hi ghl y a ut hor i t a r i a n

r el at i ons hi p bet ween anal ys t and pat i ent . Yet an ,!ideal ps yc hoa na l ys i s " ma y still be t a ke n as a model .

15 Cri t i cal t heor i s t s mi ght be ups et at t he cl as s i f i cat i on of 15olicy anal ys i s ~/s an e ma n c i p a t o r y act i vi t y, as in

ge/~eral t hey t ake a negat i ve vi ew of t he st at e and i t s agenci es in capi t al i st soci et y. The y believe t ha t t he

def ect s whi ch r e f or mi s m super f i ci al l y addr es s es ar e i nher ent in t he soci al s t r uct ur e ( Hor khei mer , 1972,

206-207). Soci al sci ence s houl d t her ef or e s pur n t he st at e and addr es s i t sel f t o t he mas s es .

16 Wh a t is in f act r equi r ed is a ki nd 3f " doubl e he r me ne ut i c " in whi ch t he pol i cy anal ys t is in a mi ddl e

pos i t i on bet ween anal yt i cal f r a me wo r k s on t he one h a n d a nd act or s in t he pol i cy pr oces s on t he ot her -

in t he s a me way a n i nt er pr et er medi at es bet ween t wo peopl e who s peak di f f er ent l anguages .

17 I n t hi s vei n, An d e r s o n (1979) a r gue s t ha t t he pr i nci pl es of a ut hor i t y, j us t i ce, and effi ci ency have a

ne c e s s ar y pl ace in a ny piece of pol i cy anal ysi s.

18 Of cour s e, t hi s pr oces s was expens i ve; t he t ot al cost of t he i nqui r y exceeded five mi l l i on dol l ar s. But t hi s

s u m pal es i nt o i nsi gni f i cance whe n set agai ns t t he s u ms of mo n e y at s t ake in t he pi pel i ne proj ect .

19 Essent i al l y, Ber ger r e c o mme n d e d t he s t r e ngt he ni ng of nat i ve r enewabl e r es our ce economi es and t he

s et t l ement of nat i ve l and cl ai ms pr i or to t he c ons t r uc t i on of pi pel i nes.

328

Re f e r e nc e s

Allison, Gr aham T. (1971). Essence o f Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. Boston, MA: Little

Brown.

Anderson, Charles W. (1979). "The Place of Principles in Policy Analysis," American Political Science

Review 73:711-723.

Banfield, Edward C. (1970), The Unheavenly City. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Berger, Thomas R. (1977). Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland. Toront o: James Lorimer.

Bernstein, Ri chard (1976). The Restructuring o f Social and Political Theory. New York: Harcourt, Brace,

Jovanovi ch.

Beveridge, Sir William Henry (1942). Social Insurance and Al l i ed Services. London: H.M.S.O.

Bleicher, Joseph (1980). Contemporary Hermeneutics. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Brown, Peter and MacLean, Douglas (eds.)(1979). Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Policy. Lexington,

MA: Lexington Books.

Castells, Manuel (1977). The Urban Question: A Marxi st Approach. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

Commoner, Barry (1971). The Closing Circle. New York: Knopf.

Cook, Thomas D. et al. (1978). Evaluation Studies Review Annual Vol. 3. Beverley Hills: Sage.

Dror, Yehezkel (1971a). Design f or Policy Sciences. New York: American Elsevier.

Dror, Yehezkel (1971b). Ventures in Policy Sciences. New York: American Elsevier.

Dunn, William N. (1981). Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction. Englewood Cliffs, N J: Prentice-Hall.

Durrell, Lawrence (1957 et seq.). Justine, Balthazar, Mount ol i ve, Clea (The Al exandri a Quartet). New

York: Dut t on.

Fischer, Fr ank (1980). Politics, Values, and Public Policy: The Problem o f Met hodol ogy. Boulder, CO:

Westview.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg, (1975). Truth and Method. New York: Seabury.

Giddens, Ant hony (1976). New Rules o f Sociological Met hod: A Positive Critique of Interpretative

Sociologies. New York: Basic Books.

Goodin, Robert E. (1980). "No Moral Nukes," Ethics 90:417 449.

Habermas, Jurgen (1970). "Towards a Theory of Communicative Competence," Inquiry 13: 360-375.

Habermas, Jur gen (1971). Knowledge and Human Interests (translated by Jeremy J. Shapiro). Boston,

MA: Beacon Press.

Hardin, Garret t (1972). Exploring New Ethics f or Survival. New York: Viking.

Horkheimer, Max (1972). Critical Theory. New York: Seabury Press.

Jencks, Chri st opher (1972). Inequality: A Reassessment o f the Effects o f Family and Schooling in America.

New York: Basic Books.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory o f Employment, Interest, and Money. London: MacMillan.

Kneese, Allen V. and Schultze, Charles L. (1975). Pollution, Prices, and Public Policy. Washi ngt on D.C.:

Brookings.

Kuhn, Thomas S. (1962). The Structure o f Scient~' c Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lasswell, Harol d D. ( 1951). "The Policy Ori ent at i on, " in Daniel Lerner and Harold D. Lasswell (eds.), The

Policy Sciences: Recent Developments in Scope and Method. St anford, CA: St anford University Press.

Lasswell, Harold D. (1971). A Pre-View o f Policy Sciences. New York: American Elsevier.

Lerner, Dani el and Lasswell, Harol d D. (eds.) ( 1951). The Policy Sciences: Recent Devel opment s in Scope

and Method. Stanford, CA: St anford University Press.

Li ndbl om, Charles L. (1959). "The Science of Muddl i ng Through, " Public Admi ni st rat i on Review 19:

79-88.

Li ndbl om, Charles L. and Cohen, David K. (1979). Usable Knowledge: Social Science and Social Problem

Solving. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lowi, Theodore J. (1969). The End o f Liberalism. New York: Nort on.

Lowi, Theodore J. et al. (1975). Poliscide: Science and Federalism versus the Metropolis. New York:

MacMillan.

MacRae, Duncan Jr. (1976). The Social Function o f Social Science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Mast erman, Margaret (1970). "The Nat ure of a Paradi gm, " in Imre Lakat os and Al an Musgrave (eds.),

Criticism and the Growth o f Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambri dge University Press, pp. 59-89.

329

Meltsner, Arnol d 3. (1976). Policy Analysts in the Bureaucracy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of

California Press.