Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas

Încărcat de

Erick AlanDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas

Încărcat de

Erick AlanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

UNDERGROUNDINFRASTRUCTURE OF URBANAREAS

SELECTED AND EDITED PAPERS FROMTHE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON

UNDERGROUND INFRASTRUCTURE OF URBAN AREAS, WROCAW, POLAND,

2224 OCTOBER 2008

UndergroundInfrastructureof

UrbanAreas

Editors

Cezary Madryas, Bogdan Przybya &Arkadiusz Szot

Faculty of Civil Engineering, Wrocaw University of Technology, Wrocaw, Poland

Taylor & Francis is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2009Taylor & FrancisGroup, London, UK

Typeset byCharonTecLtd(A MacmillanCompany), Chennai, India

PrintedandboundinGreat BritainbyCromwell PressLtd, Towbridge, Wiltshire

All rightsreserved. Nopart of thispublicationor theinformationcontainedhereinmaybereproduced,

storedinaretrieval system, or transmittedinanyformor byanymeans, electronic, mechanical, by

photocopying, recordingor otherwise, without writtenprior permissionfromthepublishers.

Althoughall careistakentoensureintegrityandthequalityof thispublicationandtheinformation

herein, noresponsibilityisassumedbythepublishersnor theauthor for anydamagetothepropertyor

personsasaresult of operationor useof thispublicationand/or theinformationcontainedherein.

Publishedby: CRC Press/Balkema

P.O. Box447, 2300AK Leiden, TheNetherlands

e-mail: Pub.NL@taylorandfrancis.com

www.crcpress.com www.taylorandfrancis.co.uk www.balkema.nl

ISBN: 978-0-415-48638-5(Hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-203-88229-0(eBook)

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Tableof Contents

Preface VII

ScientificCommittee/Reviewers IX

Sponsors XI

Problemsof trenchlessrehabilitationof pipelinessituatedunder watercourses 1

T. Abel

Buildingonundergroundspaceawareness 9

J.B.M. Admiraal

Newchallengesinurbantunnelling: Thecaseof BolognaMetroLine1 15

G. Astore, S. Eandi & P. Grasso

Numerical analysisof theeffect of compositerepair oncompositepipe

structural integrity 27

A. Bezowski & P. Str zyk

Repair of RC oil contaminatedelementsincaseof infrastructure 37

T.Z. Baszczy nski

Modellingthebehaviour of amicro-tunnellingmachineduetosteeringcorrections 45

W. Broere, J. Dijkstra & G. Arends

Trenchlessreplacement of gasandpotablewater pipeswithnewPA 12pipes

applyingthepipeburstingmethod 55

R. Buessing, A. Dowe, C. Baron & M. Rameil

ExperienceswithPolyamide12gaspipesafter 2yearsinoperationat 24bar and

newpossibilitiesfor HDD 67

A. Dowe, C. Baron, W. Wessing, R. Buessing & M. Rameil

Simulationresearchesof pump-gravitational storagereservoir anditsapplication

insewagesystems 75

J. Dziopak & D. Sy s

Newdevelopmentsinliner designduetoATV-M 127-2andcasestudies 83

B. Falter

Concrete durablecompositeinmunicipal engineering 97

Z. Giergiczny, T. Pu zak & M. Sokoowski

Flyashasacomponent of concretecontainingslagcements 107

Z. Giergiczny &T. Pu zak

Rehabilitationof roadculvertsontheequator. Implementationof innovative

opencut andjacking/reliningtrenchlesssolutions 115

J.M. Joussin

Urbantechnical infrastructureandcitymanagement 129

W. Kaczkowski, K. Burska, H. Goawska & K. Kasprzak

V

Maintenanceof drainagesysteminfrastructureinButareTown, Rwanda 141

A. Karangwa

Contact zoneinmicrotunnelingpipelines 149

A. Kmita & R. Wrblewski

Effect of variableenvironmental conditionsonheavymetalsleachingfromconcretes 155

A. Krl

Designof thepipelinesconsideringexploitativeparameters 165

A. Kuliczkowski, E. Kuliczkowska & U. Kubicka

Management of sewer networkrehabilitationusingthemassservicemodels 171

C. Madryas & B. Przybya

UtilizingtheImpact-Echomethodfor nondestructivediagnosticsof atypically

locatedpipeline 183

C. Madryas, A. Moczko & L. Wysocki

Selectedproblemsof designingandconstructingundergroundgaragesin

intensivelyurbanisedareas 193

H. Michalak

Material structureof municipal wastewater networksinPolandintheperiodof

2000to2005 203

K. Miszta-Kruk, M. Kwietniewski, A. Osiecka & J. Parada

TwoHDDcrossingsof theHarlemRiver inNewYorkCity 213

J.P. Mooney Jr. & J.B. Stypulkowski

Preliminarydesignfor roadtunnelsonTrans-EuropeanVcCorridor motorway,

sectionMostar North SouthBorder (BosniaandHerzegovina) 225

I. Mustapi c, D. ari c & M. Stankovi c

Mappingtheunderworldtominimisestreet works 237

C.D.F. Rogers

Assumptionsfor optimizationmodel of sewagesystemcooperatingwith

storagereservoirs 249

D. Sy s & J. Dziopak

Curvaturejackingof centrifugallycast GRP pipes 257

U. Wallmann & D. Kosiorowski

Reliningwithlargediameter GRP pipes 269

U. Wallmann

Undergroundinfrastructureof historical citiesasexceptionallyvaluable

cultural heritage 275

M. Wardas, M. Pawlikowski, E. Zaitz & M. Zaitz

Author Index 287

VI

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Preface

Inmostcases, townshavegrownuponthebasisof industrial capital andrelevantrulesof industrial-

ization. Ithascausedthatsuchtownsaremalfunctioning, expensive, notecological withall resulting

consequencesimpedingeveryday lifeof their inhabitants. Thus, public expectationsarethat por-

tionsof townssubjectingtomodernizationandalsoexpansionof suchtownswouldbeprogressed

withutmost considerationfor residential comfort byadaptingnewlygrowntowninfrastructureto

social, spiritual andcultural needsresultingfromchangedstyleof lifeandcontinuouslychanging

scaleof values. Creatingurbanizedspaceof suchfeatures is oneamongfundamental tasks that

needtobeundertakentofulfil theexpectationsspecifiedabove. Thistaskisalsoresultingfromthe

necessity of unifyingthetownsandadaptingthemtostandardsbecomingpopular duetoglobal-

izationprocess. Newprojectsof modernizationandexpansionof townshavingbeennowcoming

into being must bedistinguished by better-than-beforeuseof town spacethrough stereoization

of development, i.e. development of tower-block housing and underground structures. To meet

this conditionahigher level of integrationof infrastructuresystems amongwhichthefollowing

equipment isdistinguished:

equipment relatedtocommunicationservicesfor thetown;

equipmentconnectedwithpower management, water supplyandsewagedisposal system, waste

disposal andmanagement;

communicationandinformationrelatedsystems which, assumingtheneedof control, also in

respect totheremaininginfrastructuresystems, createthebasisof urbanmanagement system.

Themost important is however to work out engineeringsolutions that wouldbethebasis for

creatingintegratedstructures. Thefundamental assumptionfor suchstudies must becreationof

urbanizedspaceenabling:

toexchangeenergybetweensystems/equipmentandtousetownheatfromsomestructures, such

asfor examplecommunicationtunnels, sewagesystemor power systems, etc.

self-fillinginof thewater supplysystem(bywastewater treatment),

to rise the safety of town inhabitants both in respect of natural threats (flood, seismic and

paraseismicquakes, etc.) andexternal risks(terrorist or war actions),

tousetheprofitsresultingfromstereoizationof town, i.e. temperature, humidity andacoustic

conditionsother thanthoseexistingover theground,

toreleasethegroundspacefromsomefunctions(first andforemost thecommunicationrelated

functions) whichshall bemainlyusedfor residential andrecreational purposes,

torenovatethehistorical, cultural andecological environment of citycentres.

Thus, researches, planners and investors must focus their attention on making better use of

undergroundspaceasthepotential toimprovetowncommunication, onexpandingcentrecapacity

by movingmany commercial andservicefunctionunderground, andalso onmodernizationand

integration of underground systemto improve their functionalities and to create conditions for

constructionandoperationof other undergroundstructures.

Shouldthespecifiedtargetsbereached, apackageof administrationregulationspreferential for

undergroundconstructionwouldbenecessary, suchwhichaffects, but arenot limitedtotherules

of crediting, subsidizingor commissioningthebest solutions.

Accordingtoexperiencegainedtodateindevelopedcountrieswecanstatethattheunderground

spacewouldbe, andoftenalreadyis, usedwithoutanylimitationstogenerallyall purposes(except

residential function, whichinthisway couldget morespaceontheground). However thiswould

VII

not meanthat thetopic hasbeenexhaustedandrelatedproblemsresolve. J ust theopposite. Asit

resultsfromthematerialsincludedinthispaper, thissubjectisstill topical andmanyrelatedissues

needtoberesolved. Hence, I hopethat thispaper wouldariseinterest andinspirationfor further

examinations inpersons engagedinwidely understoodshapingof undergroundinfrastructureof

urbanizedareas.

At the end of this preface, I would like to express special acknowledgements to institutions

andcompanieswhichlogosandnamesareincludedinthisbook astheir financial support wasa

decisivefactor allowingitspublication.

Maineditor

CezaryMadryas

VIII

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

ScientificCommittee/Reviewers

Han ADMIRAAL, President of Dutch Group ITA-AITES, The Netherlands

Gerard ARENDS, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands

Rolf BIELECKI, President EFUC, Germany

Bert BOSSELER, Wissenschaftlicher Leiter des IKT, Germany

Jzef DZIOPAK, Rzeszw University of Technology, Poland

Bernhard FALTER, University of Applied Science-Mnster, Germany

Kazimierz FLAGA, Cracov University of Technology, Poland

Piergiorgio GRASSO, Vice-President of ITA-AITES, Italy

Wojciech GRODECKI, President of Polish Group ITA-AITES, Poland

Eivind GRV, Vice-President of ITA-AITES, Norway

Alfred HAACK (D), STUVA, Germany

Jens HLTERHOFF, President of GSTT, Germany

Jzef JASICZAK, Pozna University of Technology, Poland

Martin KNIGHTS, President of ITA-AITES, UK

Andrzej KULICZKOWSKI, Kielce University of Technology, Poland

Dariusz YD

ZBA, Wrocaw University of Technology, Poland

Cezary MADRYAS, President of PSTB, Poland

Herbert A. MANG, Technische Universitt Wien, Austria

Dietmar MLLER, Universitt Hamburg, Germany

Harvey PARKER, Past-President of ITA-AITES, USA

Anna POLAK, University of Waterloo, Canada

Chris ROGERS, University of Birmingham, UK

Anna SIEMI

NSKA LEWANDOWSKA, Warsaw University of Technology, Poland

Ray STERLING, Louisiana Tech. University, USA

Markus THEWES, RUB Bochum, Germany

Roland W. WANIEK, President of IKT, Germany

Andrzej WICHUR, University of Science and Technology Krakow, Poland

IX

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Sponsors

PLATINUM SPONSORS

HERRENKNECHT AG

HOBASSystemPolskaSp. z o.o

GOLD SPONSORS

INFRA S.A

REHAU Sp. z o.o.

SILVER SPONSORS

AmitechPolandSp. z o.o.

Gra zd zeCement S.A.

KWHPipe(Poland) Sp. z o.o.

XI

OTHER SPONSORS

BEWA SystemyOczyszczania

Sciekw

Dolno sl askaOkr egowaIzba

In zynierwBudownictwa

SIKA PolandSp. z o.o.

Book supported by

XII

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Problemsof trenchlessrehabilitationof pipelinessituatedunder

watercourses

T. Abel

Wroclaw University of Technology, Poland, KAN-REM Sp. z o.o. Wroclaw, Poland

ABSTRACT: All typesof collisionsof pipelineswithwater racearefrequentlysolvedbyelabo-

ratingsewertrapconstructions. Suchconstructionsareoftenencounteredinseweragesystemswhen

it isnecessarytoovercomeanobstacleandfor thisreasonbymaincollectorsof largedimensions

areused. Channelslocatedincloseneighborhoodtosurfacewater shouldbeconstantlymonitored,

sinceevery damageor failureof theunder-river pipelineor channel leading surfacewater may

causevery serious consequences. Municipal andindustrial wastes, whenincontact withsurface

water mayquicklyresult incontaminationandecological catastrophe. Surfacewater disturbwater

andseweragebalanceandinextremecases, withhighpressuresappliedtothesewer trapconstruc-

tion, theymayproduceaveryquick propagationof thedamageandfinally, constructiondisaster.

Duetoaveryspecificconstructionof asewagetrap(most frequentlylocatedunder watercourses

of Rother fix hindrances) it is impossibleto repair or replaceapipelinenetwork that is created

by sewagetrap in atraditional, dig technology. Owing to thedevelopment of civil engineering

andtheuseof trenchless technologies, restoringtheoriginal conditionof pipelines andassuring

their safeexploitationarehighly feasible. Inthepaper, examplesof sewer trapswill beprovided

andfinishedprojects of seweragesystems rehabilitation, shown. Thefirst structureto comment

onwill beawastetraponthemaindrainof DN1200locatedintheregionof Pulawy (southeast

of Poland) under KurowkaRiver. Thesewer trapiscomposedof threesteel pipelinenetworksof

DN600. RehabilitationworksconsistedinmakingshortreliningwithPEHDmodules. Thesecond

examplewill beasteel sewer trapof DN2200locatedunder dischargewater of Thermal-electric

powerstationinKonin(central Poland). RegenerationwasmadeinMaxi-Troliningtechnology.The

aimof thispaperistopresenttrenchlessmethodsof sewertrapstructuresrehabilitationandexplain

indetail all technological process as well as by-pass methods andmaterials solutions appliedin

pipelinesandsewer trapsentrancechambers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Asaresultof intensivedevelopment, routesof sewagesystemsformingundergroundpartof urban

infrastructureare, inmanyplaces, situatedindirect vicinityof other objects, particularlyinurban

areas.

Engineering objects with which collision of sewagesystems may occur are, first of all, road

and rail tunnels, communication arteries and railway lines laid in towns in trenches, navigable

waterways, water andheat supply mainlines andevenbuildings. Thesecondgroupof obstacles

that canbeencounteredwhilelayingsewagesystemsarenatural obstaclessuchaswater courses

andravines.

Dependingonthedepthof layingsewersaswell asdifferencesingradelines, theductingmay

passaboveroutesof engineeringobjectsandother terrainobstaclesor belowthem.

1

Layingasewer aboveanobstaclecanbeperformedonanaqueductor inavaultpassingover the

engineeringstructure. Whenlayingthesewer under anengineeringstructure, thefollowingthree

casescanoccur:

thesewer canrununder theobstaclewithout changeinshapeor dimensionsof thesection. The

bottomof theengineeringstructureintersectstheductingvault.

thesectionof thesewer enterstheobjectstructureonlyinitstoppart. Inthiscase, itisnecessary

tochangesectionof thesewer toaloweredonewhilemaintainingdropof thechannel bottom

andspeedinthechannel possiblyunchanged.

if thesewer entersintothestructureof thecollidingobject withitswholesection, asewer trap

shouldbeplannedunder theobstacle.

2 ASSESSINGTHETECHNICAL STATE OF DAMAGEDSEWERTRAP PIPE

Thestarting point of technology selection for rehabilitation of trap pipes, as structural element

transferringdefiniteload, ispreciseassessment of their technical state. InaccordancewithATV-

DVMK M 127, threedifferent technical statesof damagedpipecanbedistinguished. Depending

onthekindof technical state, various loads act ontheexecutedshell (grouting). Assessment of

thetechnical stateshouldbeperformedonthebasisof TV camerainspectionresults. It shouldbe

realizedthatsuchmodeof examiningthestructural stateof sewerisnotalwayssufficient. Especially

inthecaseof trapconstructionof concreteandreinforcedconcretepipes, very dangerousvitriol

corrosionof concreteoftenoccursasaresultof whichittransformsintogypsumcausinglowering

inloadcapacityof thewholestructure, evenleadingtoitslossandoccurrenceof stateof emergency.

Level of corrosioncannotbeassessedbyoptical examinationbutonlybytestingof samplestaken.

If justified, beforerehabilitation, pointrepairsshouldbeundertakenusingrobots. Insuchcase, the

recommendedsolutionistoincreasethestrengthof rehabilitatingshell over thewholelength.

3 TRAP CONSTRUCTIONSASSPECIAL CASESDURINGREHABILITATIONOF

SYSTEM

Traps areconstructions consistingof oneor morepipes whoseoperationoccurs under pressure.

Trapconstructionsoccur most frequentlyasobjectsmadefrompipesof cast iron, steel or steel in

concreteor reinforcedconcretecasing.

In case of repairing sewage systems, engineering objects as are trap constructions generate

complicationsfor applicationof trenchlesstechnologies.

Performingrepairsof sewer trapsusingtrenchlesstechnologiesrequiresconductingindividual

analysisof thecaseanddrawingupaproject, andparticularlyplanningthetechnologyfor carrying

out theworks.

Part of the trenchless methods of renovating the systemdoes not find application in sewer

traps. Characteristic features for structures surmountingterrain obstacles, causingnarrowingof

capabilitiesfor applicationof solutions, arefirst of all:

veryfrequent changesindirectionof layingtraplinesinprofile(figure1).

Locationof traplinesat largeangledisablesapplicationof most close-fittingtechnologiesdue

totheir limitationsregardingsusceptibilityat arcsandoccurrencesof deformationsthat canbe

avoided. Whenusingunconstrainedliningsincaseof occurrenceof evenminimumchangein

directionof sewer routedueto introductioninto thepipelineof rigidpipemodules of lengths

from0.6to6.0m, thetraparrangement completely disablesexecutionof repairsintheabove-

mentionedtechnologies. Technologiesof unconstrainedliningsconstituteaverygoodsolution

incaseof occurrenceof traplinearrangement asstraight lengths(figure2).

diameter of trappipes. Incaseof passagepipelines, i.e. of diameters larger than1000mm, it

is possibleto utilizeclose-fittingtechnologies enablingformationof theinsert directly inthe

2

Figure1. Changesindirectionof layingtraplinesinprofile.

sewer by thefittersthankstowhichtheir preciseexecutionisensured. For non-passagepipes,

duetoabsenceof thepossibilityof directinterventioninsidethesewer, therangeof applications

of close-fittingtechnologiesnarrowsconsiderably. Lack of possibilityof controllingexecution

of liningineverysensitivepoint (asinthecaseof passagepipes) formsaseriousobstacleand

aspect against theuseof close-fittinglinings.

trapconstructioninsewagesystemismostfrequentlyappliedincaseof surmountinganobstacle

intheformof watercourses. Suchasituationveryoftendisablesexecutionof by-passtypesystem

enablingworkingonasectioncut-off fromutilization. Most trenchlesstechniquesof repair are

applicable only on inactive systems. Lack of facility for pumping over mediumconducted

throughthepipemeant for rehabilitationdefines toacertainextent thegroupof technologies

that arepossiblefor application.

All theabove-mentionedconditionsconstitutethegroupof factorswhich, occurringsimultaneously,

limit toaverysmall groupof trenchlesstechnologiesthat arepossiblefor application.

4 REVIEWOF TRENCHLESSTECHNOLOGIESFINDINGAPPLICATIONIN

REHABILITATIONOF SEWERTRAPS

Liningsusedintrenchlessmethodsof renovatingsewagesystemtrapconstructionscanbedivided

into close-fitting and unconstrained. The former (viz. in situ form) are methods consisting in

makingliningsinsidetheexistingpipe, whereasthelatter consistsininstallationinsidethesection

under repair, of pipesor modulesof smaller dimensionsthanitsinsidediameter allows.

Close-fittingmethodsaresleevesof technical fabricsaturatedwithresinsaswell aspolyethylene

sleeves. Anexampleof unconstrainedlinings, incaseof sewer traps, is methodof reliningwith

short modules.

3

Figure2. Traplinearrangement asstraight lengths.

4.1 Sleeves of technical fabrics

Technologies fromgroup of close-fitting technical fabrics consist in inserting into the sewer a

resinous shell sleeveof technical fabric saturated with resin which, after filling with e.g. hot

water or hot air, getshardenedandadherescloselytotheoldsewer structure.

4

At present, thereareseveral variations of technical-fabric sleevetechnologies, differingfrom

themodeof introducingtheshell, kindof mediumusedcausingpressureintheshell, kindof agent

hardeningtheshell.

In certain situations, technical conditions maketheCIPP sleeveto becometheonly rational

solution. They couldinclude, for example, deformationof thesection. Consideredherearesuch

deformations as, for example, imperfections of thecross section. Inother situations, application

of CIPP sleeveis not possible, for example, inthecaseof loss of loadcapacity andbreak-down

of structureof thetrap construction utilized. At present, dueto decreasein utilization of water

andconsequently inreductioninquantity of sewage, inmany cases, reductionincrosssectionis

apositiveoperationsince, thankstothis, flowspeedincreasesresultinginimprovedself-cleaning

of thewholesystemandreductioninmaintenancecosts.

4.2 Polyethylene sleeves

Thebasic exampleof this typeof technology is Trolining system. It is a trenchless systemfor

reconstructingcombinedsewagesystemandalsosanitary, rainwaterandindustrial drainagesystems

aswell asother pipelinesbothgravitational andalsopressure, fabricatedfromvariousmaterials.

Thissystembelongstothegroupof GIPP(groutinginplacepipe) methods. Technologiesof close-

fittingliningsarecharacterizedbyeliminatingtoaminimumtheneedfor carryingoutearthworks

as areindispensableincaseof classical technologies of undergroundinfrastructurerepairs; this

facilitatesreductionincommunicationdifficulties. Animportantmatter isalsolimitationof noise,

dustandothernuisances. Deservingspecial attentionhoweveristheradical shorteningof theperiod

of workduration.

Incontrastwithliningsof technical fabricssaturatedwithresins(differinginfabricmaterial and

kindof resinandparticularlythemodeof hardening), TROLININGconsistsof polyethyleneinsert

madefromspecial kindof sheet/foil andfillinglayer.

Large-size pipes are renovated using segments of PEHD panels stiffened with solid form-

work, instead of sleeves. In case of infiltration of groundwater, panels are also used on the

outside, adhering directly onto therenovated construction, protecting thenew structureagainst

external influences. Thefreespacebetweentheinsert andthepipewalls is filledwithconcrete.

Reinforcement canfirst beinstalledinit. Thequantityof reinforcement, wall thicknessandclass

of concretearethedecidingfactorsregardingrigidityof therepairedconstruction. Thesequantities

aredefinedthroughprecisioncalculations. Therepair systemof large-sizepipesisalsoperfectly

suitablefor rehabilitationof inspectionchambers.

4.3 Example of execution

Dischargewater trapinKoninThermal-Electric Power Station.Theobject is locatedinKoninat

RybackaStreet innorthernpart of thetown. Thetrapconstructionhasthetask of carryingwater

fromthedischargeductof Pa

tnwThermal-ElectricPower Stationunder theductleadingwater to

KoninPower Station.This object belongs to thesystemof ducts andtraps whosetask is to carry

coolingwater of Pa

tnw KoninPower Plant Complex.

Theductingis madefromsmoothSt3S steel pipes withlongitudinal seamandwall thickness

of 20mmtogether withexternal andinternal anticorrosionprotection. Lengthof eachtraplineis

32.5m(figure4).

Assessmentof technical stateof thepipelinetoberepairedshowedverylargecorrosioncavities

inplaces inpipewalls. Measurements takenwiththickness gaugeshowedthat wall thickness in

certainplaceshadreducedfrom20mmto7.1mm.

Fromstructural analysisconducted, it wasconcludedthat incaseof reductionof wall thickness

to5mm, thetrapconstructionwouldloseitsstrength.

Technical statedeterminedof thepipelineindicatedthenecessityfor immediatereinforcement

of themiddlelineof thetrap. Deterioration of thetechnical stateand theresulting loss of load

capacitycouldthreatenaconstructioncatastrophe.

5

Figure3. GIPP system, TROLININGsystem.

Figure4. Water trapinKonin.

Internal forceswerecalculatedfor twoloadsituations:

caseI all loadsoccur,

caseII nowater loadinduct (pipelineisemptiedof water).

After dimensioningtheconstruction, resultswereobtainedensuringadequatetechnical param-

eters for reinforced concrete layer of 150mmdoubly reinforced with 14 rods in spacing of

100mm.

Structural andstrengthanalysisforcaseII (trapconstructionemptiedof water) indicatedthatfor

apipeof suchlargelossinwall thickness(evenupto7.1mm), itsemptyingof waterisinadmissible

sinceit couldleadtobreakdown.

Inviewof theabove, it wasplannedtoprovideapreliminaryreinforcement byinstallingrings

madeof rolled160mmchannel sections. Therings wereinstalledby divers beforepumpingout

water fromtheducting(figure5).

6

Figure5. Preliminaryreinforcement.

4.4 Relining with short modules

For rehabilitationof gravitational pipelinesbymeansof short pipemodules, themodulesutilized

areof slightlylessoutsidediameter thaninsidediameter of therenovatedpipe, e.g. for renovation

of DN300sewer, pipemodulesof outsidediameter280mmor250mmcanbeused. Rehabilitation

consistsinsuccessivejoiningof consecutivepipemodulesandsimultaneousslidingtheliningso

assembledinto theinterior of theoldpipeline. Themodules havetotal lengthfromabout 0.6m.

Thisenablescarryingout workinsidethereinforcedconcretechamber/pit andhenceit ispossible

torehabilitatethefull lengthof trapconstructionwithout performinganyearthwork whatsoever.

Availablein themarket aredifferent methods of inserting renovation modules into thepipeline

to berehabilitated. Somefirms proposepushing/jacking in themodules by means of hydraulic

actuators/jacks; other proposepullingtheminbymeansof winches.

4.5 Example of execution

Sewer trapcarryingcommunal sewagefromthetownof Puawatothewastewater treatmentplant.

Theobject islocatedontherouteof themaindrainof diameter 1200mm.

Thetrapconsistsof 3linesof diameters600mmeach, connectedtothemaindrainthroughinlet

andoutletchambers/pits. Thetrapconstructionlengthscarrythesewageunder theKurwkaRiver

whichconstitutes asmall tributary of theVistulaRiver. It was plannedto performrehabilitation

usingshortreliningtechnology. PEHDmodulesof length1mwereused.Theinstallationtechnology

consistedinpullinginthemodules by means of ahydraulic winch. Theworks werecarriedout

under difficult winter conditions withsewer inoperation. Sewagewas transferredby means of a

logstopprovidedthroughactivepart of thetrapconstruction. Thiswaspossiblethankstodivision

of thepit intocells. Beforeproceedingtoexecutetheshort relining, all thelinesof thetrapwere

subjectedtohydrodynamiccleaning. After rehabilitation, thenewpipelineobtainedwasof slightly

lessdiameter, themodulesinstalledbeingof outsidediameter 580mm.

5 SUMMINGUP

Dueto thespecifics of trap systemoperation which very often operates at 100%capacity, any

methodof rehabilitationusedmustnotleadtodeteriorationof thehydraulicconditions. Therepair

must ensureimprovement of hydraulic conditions, increaseinloadcapacity andprolongationof

7

pipelinedurability. Rehabilitationof thesaidobjectsmust becarriedout withmaximumaccuracy

andprecisionduetoinability of monitoringthelengthsof trapconstructionat operational stage.

Breakdownof sewer trap, incontrast withthewholesewagesystem, maycarrymoreseriousand

dangerous consequences withit. As aresult of sewer trapbreakdown, damagecanbecausedto

structures inits closeproximity whichvery oftenincludetheobjects for whichprovisionof the

sewer trapwasnecessary. Damagetoacommunicationarteryor water coursemaycreateadirect

hazardtopeople.

As canbeseen, theconsequences of no repairs or repairs carriedout witherrors may leadto

several failuresof structures. Sewer trapsconstituteatop-classchallengefor anycontractor under-

takingtheir rehabilitation. Thankstothepossibilityof applyingtheabove-mentionedtechnologies

for repairing such constructions, every designer has the capability of selecting the appropriate

technology and planning out the rehabilitation procedure so as to acquire long-termeffect and

protectionof theconstructionagainst breakdown.

REFERENCES

Sewagesystem. T. 1, Sewagesystemandpumpingstation. (InPolish). Kanalizacja. T. 1, Sieci i pompownie.

Baszczyk, Wacaw, 1983.

ATV-DVWK-A127P Instructions Structural analysis of sewers and sewage system pipes. (In Polish).

WytyczneATV-DVWK-A127P Obliczenia statyczno-wytrzymao sciowe kanaw i przewodw kanal-

izacyjnych.

ATV-DVWK-M 127P Auxiliary Materials Structural analysis for technical rehabilitationof sewagesystem

pipesbyintroducinglinersor bytheassemblymethod. (InPolish). MateriayPomocniczeATV-DVWK-M

127P Obliczeniastatyczno-wytrzymao sciowedlarehabilitacji technicznej przewodwkanalizacyjnych

przez wprowadzenielinerwlubmetod amonta zow a.

PN-84/B-03264 Concrete and reinforced concrete structures. Basic principles of designing. (In Polish).

PN-84/B-03264Konstrukcjebetonowei zelbetowe. Podstawowezasadyprojektowania.

Technical materials of M/s KAN-REM Sp. z o.o. (In Polish). Materiay techniczne firmy KAN-REM

Sp. z o.o.

Technical materialsof M/sTROLININGGmbH. (InPolish). MateriaytechnicznefirmyTROLININGGmbH.

Problemsof trenchlessrehabilitationof sewagesystempipes. (InPolish). Problemybezodkrywkowej odnowy

przewodwkanalizacyjnych Prof. Andrzej Kuliczkowski, 2004.

Rehabilitation of Konin trap construction Execution project. (In Polish). Naprawasyfonu koni nskiego

ProjektWykonawczy.

Testingandacceptanceof CIPPtechnical sleevesandtheir durability Andrzej Kolonko, TrenchlessTechnol-

ogy 3/2007. (InPolish). Badaniai odbiory technicznere

kawwCIPP aichtrwao s c Andrzej Kolonko,

In zynieriaBezwykopowa3/2007.

8

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Buildingonundergroundspaceawareness

J.B.M. Admiraal

Centre Applied Research Underground Space CARUS, Gouda, The Netherlands

ABSTRACT: Worldwidethedemandonavailablespaceinurbanareasisgrowing.Theawareness

that theuseof undergroundspacecanoffer asolutionisoftenlacking. Thispaper will discussthe

latest developments in thefield of underground spaceplanning. It will highlight why planning

should beconsidered in order to avoid spatial conflicts which will bedetrimental to theuseof

undergroundspace. Thepaper will alsodiscussthesustainableuseof theunderground. Giventhe

many benefits theuseof theundergroundoffers to lifeon thesurface, it is often deemedto be

sustainable. Theauthor will arguethat thisisnot necessarilyalwaysthecase. A balanceddecision

is neededwhenconsideringtheuseof undergroundspaceinwhichtheundergroundas aliving

organismshouldbeconsidered.

1 INTRODUCTION

Withtheworldwidesearchfor morespaceinurbanareas, theuseof undergroundspaceisseenas

avalidsolution. Theawarenessthatthisisthecaseisinpracticenotwidespread. Inmanycasesthe

development of undergroundspaceis autonomous withfar reachingeffects. Oneof thesebeing

that further development isseverelyhinderedandcanonlytakeplaceat great depth. Tunnellingis

seenasoneof themethodswhichcanbeappliedtousetheundergroundspace.

To prevent theautonomous development becoming common practice, avision on theuseof

undergroundspaceneedstobedevelopedat alocal level. Thisinturncanfacilitateplanningthe

useof undergroundspace, whichshouldavoidconflictsbetweenresourcedemandsandalsolead

tomulti-functional useof undergroundspace.

Inmanycasestheundergroundspaceisalivingorganism. Thiswill requirebalanceddecisions

ontheuseof undergroundspace. Onlyinthiswaycantheuseof undergroundspacebedeemedto

bepart of sustainabledevelopment.

2 UNDERGROUNDSPACEAWARENESS

2.1 The worldwide quest for urban space

Astheworldpopulationkeepsgrowing, mega-citiesaregrowingbigger andbigger. It ishowever

notonlythegrowthof theworldpopulationthatleadstothedevelopmentof mega-cities. TheUN-

HABITATprogrammehasstatedthatasof mid-2007morethan50%of theworldpopulationlivesin

cities.Thismeansthatthepopulationshiftfromrural areastourbanareasisalsocontributingtothis

growth. Oneof themost commonaspectsof mega-citiesisthestrugglefor spacetoaccommodate

all functionsrequiredtomaintainliveabilitybut alsomobility.

Citiescannot survivewithout infrastructure. Infrastructuretoallowitspopulationtomove, but

alsotheinfrastructuretoprovidethecity withitspower andwater. Utilitiesalsorequirespaceto

beaccommodated. Withtheadverseaffects of climatechange, sewer systems needto copewith

9

ever increasingamountsof rainwater. All thisneedstobetakenintoaccount. Theworldwidequest

for urbanspacerequires radical newinsights into landuse. Multiplelanduseis oftenseenas a

newwaytocopewiththeever increasingdemand. Theuseof undergroundspacemust beseenas

avalidoptionwithinthiscontext.

2.2 Sustainable development and climate change

InTheNetherlands aurgency agendawas published in 2007 by leading scientists and research

programmes, callingonthenationtotaketoheart sustainabledevelopment andtoclimateproof

thecountry. Theso-calledUrgenda provides anactionplanfor thecoming40years. Thebasis

assumptionisthatTheNetherlandswill needtochangemorerapidlyinthecoming50yearsthan

inthepast 500yearsinorder tocopewithall thechallengesthecountryisfacedwith.

Thesechallenges arebothinthesocial cultural arenaas inthecivil engineeringfield. Oneof

thestatementsintheUrgenda, isthat within15years, intensiveuseof undergroundspacewill be

commoninTheNetherlands.

For theauthors of theUrgendait is agiven fact that underground spaceusewill play avital

roleinthesustainabledevelopment of thecountry anditsclimateproofing, i.e. ensuringthat the

adverseeffectsof climatechangearemitigated.

2.3 Underground space development

Given, asshowabove, theroleundergroundspaceusecanplaywithinthecontextof theworldwide

questformoreurbanspace, thereisaparadoxwhichneedstobeaddressed.Thisparadoxbeingthat

ontheonehandmanycountriesandcitiesalreadypracticeanintensiveuseof undergroundspace

whereasontheother handthereseemstobeaworldwideignorancetothefact that underground

spacecanplayavital roleinalleviatingthespatial shortagesat surfacelevel.

Thisparadox isoneof thereasonsfor settinguptheITA CommitteeonUndergroundSpace

ITACUSbytheInternational TunnellingandUndergroundSpaceAssociation, ITA-AITES. World-

widemany Westerncities arefindingtheneedto go deeper anddeeper into theundergroundas

thetoplayersarealreadycongestedwithvariousfunctions. Usersof transport systemsneedtobe

transportedtogreat depthas thetoplayers areusedfor utility systems. This fact arises fromthe

autonomous development of undergroundspacewithout any formof coordinationandnovision

bycityauthoritiesonmultipleuseof undergroundspace.

Theauthor hasoftenpubliclystatedthat thegoal toachieveintensiveundergroundspaceusein

TheNetherlands withinthenext 15years is unreachableif thecurrent practiceof uncoordinated

use of underground space remains. The autonomous development will lead to a chaos in the

undergroundwhichwill makefuturedevelopment impossible.

Another problemwhicharisesfromthelackof awareness, isthesimplefactthatdevelopmentof

forexampleinfrastructurewill takeplacewithoutevenconsideringthepossibilitiesof underground

spaceuse. Thiscanleadtousingcontemporarymethodswhichoftengiveasuboptimal resultsas

reportedbytheauthor (Admiraal, 2004).

Awarenessof thepossibilitieswhichundergroundspaceusehastooffer isthereforeneededon

alargescale. Not onlytoensurethat thisuseisconsideredright fromthestart of development of

cities, but alsotoensurethat oncedevelopment takes place, it is doneinacoordinatedway. The

roleof ITACUSwill be, toprovideaplatformfor aworldwidedialogueontheuseof underground

space. A dialoguewhichwill consider theuseof undergroundspacewithinthecontext of societal

needs, environmental concerns, sustainabledevelopment andtheclimatechallenge.

2.4 Underground space use

There seems to be confusion in practice on what the use of underground space entails. Often

tunnellingis seento bethesoleuseof undergroundspace. This is trueinso far that tunnelling

is amethod which allows for various functional uses of underground space. Transport Useand

10

ProductionUseof theundergroundcall for tunnelstomakethispossible(Admiraal, 2006). There

arehowever many other uses whichall competefor spaceintheunderground. This fact initself

requires abalanceddecisiononhowto developundergroundspace(Parriaux, Blunier, Maire&

Tacher, 2008). A further complexityisaddedwhenwerequirethisdevelopment tobesustainable

aswill bediscussedlater inthispaper.

As Parriaux and others point out, underground space can be modelled as consisting of four

differentresources: space, water, geo-material andgeo-energy. All theseresourcescanbeused, but

theseusescanconflictwithvariousresults. Theseresultscanvaryfrompollutionof drinkingwater

totransportationprojectsnot beingcarriedout. Thereisneedtoconsider theuseof underground

spaceinitsentiretyandnot limit it totunnelling.

3 PLANNINGBASEDONVISION

3.1 Action without vision

A J apaneseproverbstatesthat: Visionwithoutactionisadaydream, actionwithoutvisionanight-

mare. As statedabove, withrapidautonomous development of undergroundspace, anightmare

situationcanariseas city planners discover thechaos whichexists underground. InTheNether-

lands and in Chinatheneed for creating avision on theuseof underground spaceas thebasis

for aplanneddevelopment is understoodandput inpractice. Althoughthescaleis still limited,

interestingresultscanbereported. Thecityof ZwolleinTheNetherlandswasthefirst todevelop

avisionontheuseof theunderground.

Oneof theinterestingresultsof thisvisionwastheidentificationof pollutedgroundwater under

anewurbandevelopment area. This has leadtotheideatocombinetheapplicationof heat-cold

storagewiththecleaning-upof contaminatedgroundwater over aperiodof 10years. Inthisway

theenvironmentisservedintwoways: thegroundwaterisdecontaminatedandthecarbonfootprint

for thedevelopment areaisreducedasnogasor electricityisrequiredtoheat thehousesinwinter

or cool themduringsummer.

Inthecityof Shanghai inChina, apilot project isbeingcarriedout wherebyfor newdevelop-

ments of thecity, undergroundspacemust beincludedintheplanningof thedevelopment. It is

evidentthatthissituationwill leadtoacoordinateddevelopmentinwhichanoptimal useof under-

ground spaceis ensured. Chinais aprimeexampleof acountry wheretheuseof underground

spaceismoreandmoreseenaspartof urbandevelopment. Visionandplannedactionisparamount

for acontrolleddevelopment of undergroundspace.

3.2 Conflicts between resources

Themainproblemwhichcanarisefromnot planningtheuseof undergroundspacecanbebest

explained by two examples. As natural energy resources are seen to be limited, the search for

alternativesisalsoaworldwideevent. Oneof themost promisinginthisareaistheapplicationof

geo-thermal energysystems. Theapplicationof thesesystemsdoeshowever requirevertical pipes

tobeinsertedintoundergroundspace, oftenhundredsof metersdeep.

Theuseof thesesystemsisverypopular andarapidautonomousdeployment of thesesystems

isobservedbothinGermanyandTheNetherlands. Thedownsidetothisisthat thesesystemscan

becomeaseriousobstaclefor futuredevelopment of undergroundspaceinthehorizontal plane. It

isnot unthinkablethat futurealignmentsof undergroundmassrapidtransport systemsisseverely

hinderedbythepresenceof thesesystems.

Moreover, as observed by Parriaux, Tacher & J oliquin (2004), when a decision needs to be

made for an underground mass rapid transport systemor a geothermal application, the first is

mostlychosen. Inanycase, noconsiderationisgiventothepossibilitytocombinethesefunctions.

Althoughnot deemedto befeasiblefromanengineeringperspectiveonthemoment, thereis no

reasonwhyinfuturethisshouldnotbethecase. Thepointbeingmadehereisthatwithoutplanning

thesesituationscannot beidentifiedandthereforeinnovationasmentionedisnot stimulated.

11

A second examplestems fromtheconflict which arises fromseeing underground spaceas a

unlimitedreservoir of spaceversusundergroundspaceasanaturereservewhichneedstobepre-

servedat all cost. Thisconflict arisesfromthefact that inmoreDeltaicregions, giventhespecific

character of thesubsoil, it is deemedto bethesupporter of lifeon thesurface, given themany

natural processesandsystemsthat exist belowthesurface. Inonecasethisconflict hasleadtoa

tunnel projectbeingscrappedinTheNetherlandsfor fear of changingthecharacter of theNaarder

Lake, alakedeemedtobepart of anareaof outstandingnatural beauty.

That thefear initself is not unfoundedcanbedemonstratedwiththeadverseeffects of water

inflowintunnels as experiencedinNorway (Grv, 2008). AlthoughthesituationinNorway and

TheNetherlandsarenotcomparable, thelackof understandingthattheconflictbetweenthesetwo

approachesexists, liesat thebasisof thedecisiontakennot tocarryout theproject.

A balanced-decision making framework for the use of underground space can avoid these

conflicts. Parriaux andothers, areworkingonthedevelopment of suchframeworks. Theimple-

mentationof theseframeworkscanhowever onlytakeplacewhenthereisageneral awarenessof

thevirtuesof theuseof undergroundspace, thisawarenessistranslatedintoavisionwhichinturn

makesplanningpossible.

3.3 Planning methods in practice

Variousmethodsareinuseregardingtheplanningof undergroundspace. Asreportedbytheauthor

(Admiraal, 2006) researchinTheNetherlandshascomeupwithpractical methodswhichidentify

areaswhicharemost likelytoproveworthwhilefor undergroundspacedevelopment. Theseareas

areidentifiedby takingvariousaspectsintoaccount. Other methodstry toapproachtheproblem

fromatheoretical sideand useasystems approach on which decisions can bebased (Parriaux

et al, 2008). Themost commondevelopment istofocusonareasfor development rather thanon

individual cases.

Theso-calledareadevelopment approachoftenincorporatesadialoguebasedmodel inwhich

all interestedstakeholdersareinvolved. Plannersthenusetheoutcomeof thisdialoguetodevelop

astakeholder basedvisiononwhichtheplanningcanbebased. Inthisapproachtheinterestsof all

parties aretakenintoaccount andtheconflicts as observedabovecanbeavoidedas all interests

areweighed-up.

Aninterestingtool for analysisistheso-calledlayeredapproach toareadevelopment. Inthis

approachanareaisdeemedtoconsist of threelayers: habitation, networksandtheunderground.

ThemethodhasbeendevelopedbytheMinistryof Housing, Spatial PlanningandtheEnvironment

inTheNetherlands. Thefact that theundergroundis recognisedas anentity to beconsideredin

futureplanningissuesisapositivedevelopment.

The city of Arnhemin The Netherlands is actively using this approach for the planning of

developmentswithpositiveresultsintermsof undergroundspaceuse. Oneof theresultsbeingthe

combinationof functionsunderground.A primeexampleisthedevelopmentof anundergroundcar

parkincombinationwithanutilitytunnel whichincorporatesanundergroundwasterefugecollec-

tionsystem. Inothercitiesthesedevelopmentswouldeventuallyhavetakenplaceonanautonomous

scale. Inthisexamplethecombinationof thesefunctionsthroughplanningbasedonvisionmakes

it anexcellingbest practiceexample.

4 THE UNDERGROUNDASLIVINGORGANISM

Theuseof undergroundspacetakesplaceindifferentregionsof theworldwithvaryinggeological

conditions. Mega-citiesaremost commonly foundwithin50kmof thesea. Thismakesthat alot

of mega-citiesandthereforeundergroundspacedevelopmenttakesplaceinDeltaicregions. These

Deltaicregionshaveincommonthattheundergroundconsistsof softsoilsbeingoldriverdeposits.

Theregionsalsohaveincommonthat theyareoftenveryfertile, providinglandfor cropgrowth.

12

In Deltaic regions, the underground can be modelled as being the supporter for life on the

surface as mentioned before. The time scale at which processes take place in the underground

variesdramaticallyfromlifeonthesurface. Comparetoappreciatethisthetimeittooktoproduce

coal, gasandoil asnatural resourceswiththelifespanof anaveragebuilding. Theargument being

madeisthatweoftenarenotawareof theeffectsof manmadeinterventionsinthesubsoil. A prime

examplebeingthecontaminationof drinkingwateraquifersthroughstorageof wasteinthesubsoil.

TheNetherlandsisstill facingamassiveclean-upoperationtothiseffect.

Theuseof undergroundspaceaspartof sustainabledevelopmentmustconsider theabovewhen

decisionsaretaken. Itclearlyillustratesthatautonomousdevelopmentof theundergroundnotonly

canleadto resourceconflicts as mentionedinthecaseof transport versus geothermal energy. It

canalsoleadtodevelopmentswhichmayprovetobenon-sustainable.

In general it is felt by the author that resource conflicts can be avoided and a sustainable

development of underground space can be achieved through planning. In the case of the city

of Zwolle, the combination of a geothermal application with decontamination of groundwater,

clearlyshowswhat canbeachievedthroughvisiondevelopment.

5 CONCLUDINGREMARKS

Theuseof undergroundspaceisseentobevital inaworldwheremorethanhalf of thepopulation

nowlivesinurbanareas. Further concentrationinmega-citiesisatrendwhichcannot bestopped.

Theuseof undergroundspacecancontributetosustainabledevelopment, maintainingliveability

andpreparingtheworldfor theimpactof climatechange. Creatingawarenessontheuseof under-

groundspaceinthisrespect isvital. Furtheringthedevelopment of visionsonurbanunderground

spaceuseandrational useof theundergroundspacethroughplanningtechniquesisessential.

Thefutureof undergroundspaceuseisfurthermoregovernedbytheabilitytocombinefunctions,

e.g. combinationof transportfunctionswithwatermanagement.Thisrequiresadialoguewithincity

authoritiesacrosspolicyboundaries.Theresultscanhoweverbeverypositiveasisdemonstratedby

theStormwater ManagementandRoadTunnel projectwhichisnowoperational inKualaLumpur,

Malaysia.

Theabilitytoplantheuseof undergroundspaceincombinationwithamulti-functional usewill

determinethefutureof undergroundspaceuseasavaluablecontributor totheworldwidequestfor

moreurbanspaceandasustainabledevelopment of mega-cities. It will alsoshowthat societycan

reallynot affordnot touseundergroundspace.

REFERENCES

Admiraal, J.B.M. 2004. Developingaknowledgeinfrastructurefor undergroundspaceinIndonesia. Proceed-

ing7thJ oint MeetingJ TA-COB, StichtingCOB, Gouda, TheNetherlands.

Admiraal, J.B.M. 2006. A bottom-up approach to the planning of underground space. Tunnelling and

UndergroundSpaceTechnology, Volume21, Issues34, Pages464465.

Grv, E. 2008. Watercontrol inNorwegiantunnelling. ProceedingSouthAmericanTunnelling2008. Brazilian

TunnellingCommittee CBT, SaoPaulo. Brazil.

Parriaux,A,Tacher, L. &J oliquin, P. 2004.Thehiddensideof cities towardsthree-dimensional landplanning.

Energy& Buildings, Volume36, Pages335341.

Parriaux, A, Blunier, P, Maire, P. & Tacher, L. 2008. Theurban underground in thedeep city project: for

construction but not only. Proceedings Underground space challenges in urban development, Stichting

COB, Gouda, TheNetherlands.

13

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Newchallengesinurbantunnelling: Thecaseof BolognaMetroLine1

G. Astore, S. Eandi & P. Grasso

Geodata SpA, Turin, Italy

ABSTRACT: TheLine1of BolognaMetrois7kmlongwith12stationswhichcrossestheentire

city fromtheFieraDistrict totheMaggioreHospital. Thesystemadoptedisalight rail tramway

operatedwith34-mlong, single-unit vehicles. Thelineisdesignedtobecompletelyunderground

and its construction involves theuseof all theavailabletunnelling technologies: cut and cover,

TBM and NATM. Theportion of thevertical alignment in thecity centreis very deep to avoid

damagetobuildingsandtoallowthelinetounderpassthenewHighSpeedRailwaytunnel nearthe

Central RailwayStation, whereit isforeseenaninterchangewiththemetro. ThePiazzaMaggiore

Stationisthemost complex andimportant intheentirelineandrepresentsagreat challenge, for

designersinparticular, becauseatthisstationsitethehorizontal alignmenthasaturnof 90

which

hastobebuilt completelybyconventional tunnellingtechniques.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 The Bologna Case

Locatedinnorthernpart of Italy, Bologna, amedium-sizecity withabout 400.000residents, has

anancienthistorical centreandcanbeconsideredastheheartof Italianroadsandrailwaynetwork.

Infact, its uniqueposition, beinginthecentreof acrossroadlinkingnorthto southandwest to

east of Italy, createsahugedemandfor publictransportationsystems.

As amatter of fact, to improveandchangethecity layout, at least four infrastructural works

will bebuiltin10yearstime: anewhighspeedrailwaystation; apeoplemover connectingrailway

stationtoairport, animportant linefor trolleybuscalled(Civis); andanenforceableMetroline.

Intheplannednetwork, themetroLinerepresentsoneof themostcomplexworksbecauseof its

length(7km) anddepth, alignment, anddifficultiesinconstructingthecivil works.

Themainconstrainsarethepresenceof old-built citycentrewithhistorical monumentsandthe

possibilityof thearcheological findings, entailingthemetrolinetobecompletelyunderground.

Geodata, leader of ateamconsisting of other design firms, has developed for theCommune

of BolognatheFinal Designof thewholemetro line, whichincludes thecivil works, theE&M

installationsandthetramwaytracksystem, besidesthegeological andenvironmental studies.

1.2 Description of the Metro System and the main project data

Bologna will be equipped with a semi-automatic tramway systemwith drivers aided by ACC

(Automatic&CentralizedControl system), asystemwhichallowsfor monitoringandtele-control

of trains andsubway traffic, andbyATP (AutomaticTrainProtection), asystemfor controlling

thespeedanddistancebetweentrainsaswell asfor managingthemobilizationof trains, oncethey

havearrivedat thestation.

Eachstationis to beequippedwithplatformscreendoors that separatetheplatformfromthe

train. Thesescreendoorsrepresent arelativelynewtechnological additiontomanymetrosystems

15

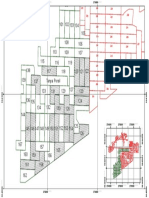

Figure1. Schematicplanof theentireline1fromFiera(right ontop) toMaggioreHospital (left).

aroundtheworld, withsomeplatformdoorsaddedtotheexistingsystemslater. They arewidely

usedinAsianandEuropeanmetrosystems.

The modern low-floor rolling stock will run with 2 headway during peak hours in the

undergroundsection, elsewherewith4 to6 maximumfrequency.

Theprincipal characteristicsof thelineare:

Total length=7800m

Semi-automatictramwaysystem(Driver aidedbyACC /ATP technology)

Undergroundstations=12

Surfacestations=1

Ventilationshafts=11

TBM(Tunnel BoringMachine) tunnel length=5600m

Cut & Cover tunnel andU-shapedsectionlength=800m

Conventional tunnel length=200m.

2 GEOLOGICAL ANDGEOTECHNICAL SETTING

2.1 Geology

Thegeologyof thetoplayersmaybeoutlinedthroughdividingthealignment intothreesections,

eachof whichhaspeculiar characteristicsintermsof thedepositional stratigraphy.

Thefirst section(fromMichelinostationtoFSstation) andthethirdone(fromSaffi stationto

MaggioreHospital station), correspondingrespectivelytotheeasternandwesternsideof theroute,

arecharacterizedby alternatepresenceof gravel-sandsedimentary layersfromriver channel and

variablebandsof silt andclayfromfloodplain. Theintermediatesectionconcerningthehistorical

towncentre(fromFS stationto Saffi station), by contrast, consists almost entirely of finesoils.

Coarsesedimentary bodies arealmost absent andthemainstratigraphic markers arerepresented

by paleosols, passingthroughsoil bands, richof organic matter onthetop, to over-consolidated

bandswithalot of carbonateconcretions.

This stratigraphic layout is consistent withthewell-knowngeomorphologic framework of the

Bolognavalley. Inparticular, inthiscasetheextremesof thealignment crossalluvial cones, while

thecentral sectionpassesthroughpredominantlyfineinter-coneareas.

16

Thesoil-layers attitudesreflectapproximatelythecomplexgeological realityof theprojectarea,

characterizedalmostexclusivelybyalluvial depositswhich, bytheirlenticulargeometry, showhigh

vertical andlateral variations.

2.2 Geotechnical setting and hydrogeological regime

Thedesigngeotechnical model of theproject has beendevelopedonthebasis of historical data

andnewsurveycampaignscarriedout in2007inthecourseof itsdesigndevelopment.

Thedepthof boreholes is directly linkedto thedepthof thestations andventilationshafts, in

order toprovideareliabledefinitionof designparametersalongtheentireline.

Duringthesiteinvestigationmany in-situgeotechnical testswerecarriedout suchasStandard

PenetrationTest (SPT) andalsoundisturbedsoil sampleshavebeenobtainedfor laboratory tests.

Otherinsitutestscarriedoutwere: conepenetrationtestswithpiezocone(CPTU) tomeasurepore-

water pressure; insitudissipationtests for evaluatingthecoefficient of horizontal consolidation

andhorizontal hydraulic conductivity; Seismic Dilatometer Marchetti Test (SDMT) for defining

thedynamicpropertiesof thesoils. Finallyall boreholeswereequippedwithapiezometer inorder

tomeasurethehydraulicheadintheaquifersalongtheentireroute.

Inthefirst 40mit canbefoundamultilevel groundwater aquifer. It consists infour different

levels, partiallysaturatedandlocallyunderpressure, namedrespectively, frombottomtotop: SUP1,

SUP2, SUP3andSUP4. Groundwater levelsSUP1, 2and3arelocatedinsandsandgravels, while

SUP4is includedinsands, limes andsilts, moresuperficial (6to 7mfromsurface). Inany

case, SUP3andSUP4cannotbeeasilydistinguished, particularlywherethesoilschangefromone

typetoanother.

Tunnel andstations do not touchthedeepest groundwater level (SUP1), but they areaffected

mainlybySUP3andSUP4

TheGeotechnical unitsarereportedbelow.

Geotechnical unitA Gravel layers

Thisunit isformedbylensof coarsesand, gravelysand, gravel withsand, andsandygravel, and

clastsuptoapproximately 8cm, aswell asrarepebbles. Thethicknessof thesoil lensare6to

8m(NSPT=1550, innocaserefusal). ItislargelypresentintheMichelino-FSstationsection

(Fig. 2) andpartiallyinthesectionbetweenMalvasiaandMaggioreHospital. Theunithasgood

permeabilityandhostsmajor theaquifersof Bologna(SUP1, SUP2, SUP3)

Geotechnical unit B Cohesionlesssands

This unit consists of uncemented sands, fromcoarseto fine, sometimes silty, predominantly

saturatedsoils. SPT valuesdonot showparticular granulometric differences. Thecoarsesands

arelesscompactedthanthefineones(NSPT<10, until 2).

Geotechnical unit C Finecohesivesoils

Thisunitincludesfinesoilswithacohesivebehaviour, mainlysiltyclayandclayeysiltwithpeat

trails. Itistheunitthatismostinterceptedbythemetroalignment, mainlyinthesectionbetween

FSStationandSaffi station.

Table1showsthegeotechnical propertiesof thethreeunitsdefinedfor thedesign.

3 TUNNEL CONSTRUCTIONTECHNIQUES

3.1 Main constraints and adopted solutions

A very complex and time-consuming work in ahistorical, urbanized areais always achallenge

for designers. Inthecaseof BolognaMetro line1, different anddifficult items wereconsidered

in planning and designing theunderground works such as tunnelling under water tablein very

poor ground conditions, underpassing of buildings particularly at historical places, protecting

archeological findings related to the Roman era, siting of stations, exits and ventilation shafts

17

Figure2. A part of thegeological profilenear BologninaStation.

Table1. Geotechnical parameters

Unit

n

[kN/m

3

]

p

[

] c

[kPa] c

u

[kPa] E

[MPa]

A 1820 3036 0 4080

B 1820 2630 0 2040

C 1920 2228 020 50150 1040

bothincitycentreandincommercial andcongestedareas(at north-east of thetown), minimizing

construction-siteareas, andmanagingintensivesurfacetraffic.

Inthelight of theaboveconstraints, thesolutionsadoptedfor theproject are:

theentirelineforits7.8kmlength, isconceivedtobeundergroundwithaconfigurationof single

tube, doubletrack and thedesigned solution provides systematic recourseto themechanized

tunnelling;

external superficial tunnelsaredesignedascutandcover sectionsinorder torealizeconnections

betweenthedepotandtheMichelinostationatthenorthsideandbetweentheOspedaleMaggiore

stationandtheMalvasiastationat thewest side; and

for special situations, short conventional tunnels areforeseen, like, for example, inthePiazza

Maggiorestation.

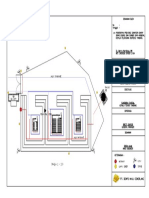

Specifically, therunningtunnel will berealizedusinganEPB Shieldwithadiameter equal to

9.80m, whichcanensure(Fig. 3):

aninternal tunnel diameter of 7.90m(functional minimum=7.80m, plus10cmof tolerance);

tail voidof 15cm;

18

Figure3. TBM tunnel typical section(left) andEPB operational scheme(right).

final liningthicknessof 35cmwithanominal lengthof 1.4m;

eachringof precast segmentsistaperedtonegotiatethecurvedtunnel alignment;

thejointsbetweensegmentsaretobesealedusingeither neoproneor hydrotitegaskets.

Thekeyobjectivescontributingtotheabovechoices:

alteringaslittleaspossibletheoriginal stressstateof thesoils;

avoidingunnecessary, extra-excavations inorder to control theexcavation-inducedeffects on

thesurface(subsidence).

TheEPB excavation modecan providecontinuous support to thetunnel face, with thesoils

excavated by thecutting head accumulated under pressurein theexcavation chamber and then

extractedbyarotatingconveyor.

Geodatahassuccessful experienceintunnellingwithEPB-TBMsinBolognabecausein2006

Geodata was involved in the construction studies and technical assistance during the works of

two parallel tunnels (9,4mdiameter and 6.112min length each) of the Bologna high speed

railway line (especially Lot 5 of urban penetration in the quarter S. Ruffillo in the south of

the city and the new central station). Both tunnels were realized by EPB-TBMs. The suc-

cess was reflected by the tunnel daily production rate and the solutions to prevent damage of

buildings.

IndesigningtheMetro Line1Geodatahas usedthetechnical andenvironmental known-how

learneddirectlyfromthehigh-speedrail tunnel. Inparticular, back-analysisof theobservedsettle-

mentshavebeenmadetodeterminetheparameter values(Vpek, OReillyandNew,1992), which

arenecessaryfor input tothesubsidencepredictionandbuildingriskassessment.

3.2 Risk analysis of buildings and soil improvement design

Potentially, buildingsaffectedbytunnelingareasmanyas400, of which35areunderpasseddirectly

bylineor stationtunnels. Insuchsituations, acomprehensive, detailedsurveyin-situwascarried

outtocollectandorganizecritical buildingdata. Thecrucial parametershavebeenmanagedusing

aGISsysteminorder tofaciliatetheassessmentof potential buildingdamagesduetounderground

works: excavationof tunnels, stationsandshafts.

Theevaluationof critical buildingsrevealedthatwhereexpectedsettlementsarenotcompatible

withprescribedsafety limits, thedesignhadto apply soil improvement: principally jet-grouting

(Fig. 4) or compensationgroutingintheverycritical arealikeBolognina.

19

Figure4. Soil improvements: tunnel crown completely grouted (left) or grouted wall to protect building

edges(right).

Figure5. Typical station assonometric view(left) andinternal renderingof stairsconnectingatriumwith

mezzanine.

4 TYPICAL STATIONS

4.1 Functional and architectural layout

Thestationsaretheconnectionsbetweenthesurfaceandtherunningtunnel andbetweenthetown

andtheline; withthispoint of viewthefunctional layout of astationisdefinedinorder to:

reducethelengthof thepathstoandexit fromtheplatforms;

createawide, bright spacewherepassengerscaneasilyrecognizetheright directions;

locateaccesswherepedestrianflowsaremost significant;

minimizethevolumeof theentirestation.

Inparticular, thearchitectural imagechosenforeachstationisbuiltonthepurityof thevolumes,

inwhichareavoidedscarcement andblindspots; theclarityof functional space, wherestairsand

elevatorsarealwaysvisibletousers; andtheusageof finishingandfurnishingelementsarechosen

for simplicityandelegance.

With theabovedesign principles in mind, 9 out of the12 underground stations aredesigned

accordingtoatypological scheme, whichis18mwideand42mlong, andliesatanaveragedepth

varyingfrom15mto25m. Theplatformsareseparatedfromthetracksbyplatformscreendoors.

20

Figure6. PiazzaMaggioreStationplanviewanddetail of TBM passage.

4.2 Constructive method

Typical stationsaretobebuiltwiththetop-downvariantof thecutandcover method. Thissolution

permitstoreduceconstructiontimesandworksiteareas, Infact, thesurfaceareasabovethecover

slabcanbereturnedtothecityfor realizingparking, viabilityor constructiondepot.

The principal construction phases are: diaphragmwalls built by hydromill; construction of

concretecoverslab; excavationunderthecover; constructionof bottomslab; buildingotherinternal

concreteworksfrombottomtothetop.

Thestationsof PiazzaMaggiore, RivaRenoandFS differ fromthetypological scheme. Inthe

nextsectionadescriptionof thePiazzaMaggiorestationwill begiven, whichisnodoubtthemost

significant pieceof workof thewholeBolognametroproject.

5 PIAZZA MAGGIORE STATION

5.1 General problem

ThePiazzaMaggioreStationis locatedat ahistorical squareof Bolognawheretwo major roads

crossthetowncentre: viaIndipendenzaandviaRizzoli, withalotof critical andhistorical buildings

andalack of spacetofor constructionsites. For all theseconstraintsthePiazzaMaggioreStation

itself canbeconsideredasaproject inthemetroproject.

Thestationis150mlongandpositionedonacurve(with25mradius), thestationplatformson

thetwosidesshall bestaggeredinorder tooptimizetheunusual shapeandpermit aneasier train

stoppage.

Thisstationhas4principal constitutingelements(Figs6, 7):

Platformtunnel onacurvetobebuilt withconventional tunnellingmethod;

Largeaccessshaft, usedalsoasconstructionshaft;

21

Figure7. PiazzaMaggioreStationlongitudinal section(A-A sectioninFigure6).

Platformaccesstunnelstoconnect shaftswithplatforms;

Existing underground atrium. This structure will be upgraded to create a new atrium for

passengers, but during construction it will be used as storage area to minimize demand for

surfacearea.

The25mcurveisnot aproblemfor thetramwayalignment itself, becausetrainswill approach

thecurveslowly, leavingafter stoppingat theplatform. However, intheconstructionphaseit has

topermit theTBM topassthroughthat becomeafundamental point intheentirework. Generally,

aTBM of therequired sizecan not excavatecurves with aradius of curvatureless than 200m.

Furthermore, inthisparticular casethereisalsonot enoughspacetoextract theTBM fromashaft

locatedat oneendof thestationandlower it downat theother. For thesereasonsit isdecidedto

createaconventionally-excavatedplatformtunnel withawidecross-sectionshapeto permit the

shieldedTBM topassthroughthealready-excavatedstationspace.

TheTBM passingphasecanbedetailedas follow: shieldmachineenters fromthenorth(via

Indipendenza)inthealready-excavatedtunnel; backuparedismounted; theshieldismovedthrough

thecurvewithaspecial trolleysystemtothenewstartpositionalignedtoviaRizzoli; shieldstarts

excavationinthenewE-Wdirectionwithback-upre-connectedtotheshield.

5.2 Tunnel and shaft calculation

Suchacomplexworkneedsimpressivestudiesandcalculationstocheckthestructural solidityand

minimizerisksinall constructionphases, beinginthetowncentre.

Constructionphaseshavebeenstudiedfor alongtimewithexpertsinconventional andmech-

anizedtunnelling, groundimprovements, undergroundworks, etc. inorder tobesurethat sucha

work canbeaffordable. Principal constructionphaseshavebeenusedtodefine: preliminary and

definitivelining, extensionandtypeof soil improvements, internal tunnel shape(minimumtomove

TBM incurve), connectiontunnelsprincipal parameters(Fig. 9).

Thecircular shaft, fromwhichcurvedplatformtunnel andaccesstunnelsshouldbeconstructed,

will beconstructedfirst. Being20mindiameterand39mdeepwithdiaphragmwallsof 45mlong,

thecircular shaftwill beexcavatedusingcut&cover top-downmethod. Theshafthasintermediate

slabs, every4.8m, tocreatesupport for stairsandtostabilizethediaphragmwallsthemselves.

Bottomslab has an arched invert shape in order to reduce bending moment and to transfer

bendingforcesstemmingfromcompressivegroundwater forcesonthediaphragms.

22

Figure8. Renderedassonometricviewof thePiazzaMaggioreStation.

Figure9. Major constructionphasesof thePiazzaMaggioreStation.

23

Figure10. 2Dand3Danalysisperformedinaccessshaft design.

Figure11. Conventional platformtunnel FEM analysis. Model andsettlementsresult.

Both2DFiniteDifferenceMethod(FDM) usingFLAC and3DFiniteElement Method(FEM )

usingANSYShavebeenusedtoevaluatebendingmoments, shearandaxial forcesonthediaphragm

walls, creatinganaxial-symmetricmodel with3Danalysistosimulatethecreationof largeopenings

inthestructure(Fig. 10).

For thecurvedplatformtunnel, thetop-headingandbenchinvert techniqueisconsideredtobe

moresuitablegivenitsbigcross-sectionareaof 170m

2

. Thislargesectionrequiressomespecial

attentionsincalculatingtheinternal structuresandinevaluatingthesettlement effectsonsurface

buildings.

This conventional tunnel is tobebuilt insoils withvery poor geotechnical characteristics and

closetobuildingsandmonuments.Thus, theconstructionisconditional tointensegroundimprove-

ment. Thetechniquestobeusedarejet-groutingandsoil freezing. J et-groutingisusedwherethere

isenoughspacetoworkwithout largeinterferencetosurfaceactivities, whilesoil freezingisused

wheresurfaceworks arenot allowed. Compensationgroutingis alsoforeseeninsomeparticular

situations liketheunder-passing of acritical historical building or to prevent settlements in the

morecritical sectionsof tunnel, wherecurveisat most.

Likefor theshaft, thetunnel isalsodesignedusing2D(PHASE 2) and3Dnumerical analyses

(FLAC3D), modellingtheexcavationsequences. A seriesof PHASE 2analyseswascarriedoutto

identify themoresuitablesolutioninterms of theconstructionsteps, andthetypeandextent of

groundimprovement (Fig. 11).

24

6 CONCLUSIONS

TheBolognaMetroline1representsareal challengefor designers. Asamulti-constrainttunneling

conditioninurbanarea, thedesignof theBolognametro project demandedspecial attentions to

link properly theobstaclecomponents of theprojects, namely, conservationof ahistorical town,

preservationof buildingsandmonuments, andminimizationof thesuperficial impacts. All these

constraintsledtoaverycomplexconstructionwork. ThejobdifficultyatPiazzaMaggioreStation

broughtaboutalsosomechallengeabledesigncriteria, of whichthemostnoticeableare: astaggered

platformsolutiononcurve, anewtechnical approachinusingEPBTBM, aspecial solutiontopass

through thecurvewith avery small radius. Theproject also demanded for an extensiveuseof

theavailablegroundimprovement techniques: freezing, jet-grouting, compensationgrouting, etc.

The solutions illustrated in this paper should be valuable for those who have to design similar

undergroundworksinanalogousurbanconditions.

REFERENCES

Amorosi A. &FarinaM., 1994. Stratigrafiadellasuccessionequaternariacontinentaledellapianurabolognese

mediantecorrelazionedi dati di pozzo. 1st EuropeanCongress onRegional Geological Cartography and

InformationSystems, Bologna(Italy), J une1316, 1994. Volume5, 1634.

Amorosi A. & FarinaM. 1995. Large-scalearchitectureof athrust-relatedalluvial complex fromsubsurface

data: theQuaternarysuccessionof thePoBasinintheBolognaarea(northernItaly). Giornaledi Geologia,

57/12, 316.

GeodataS.p.A., 2007. Metrotranviadi Bologna Final designdocumentation.

Guglielmetti et. al., 2007. MechanizedTunnellinginUrbanAreas. Taylor & Francis.

Marchionni V.&Guglielmetti V.2007EPB-Tunnellingcontrol andmonitoringinasensitiveurbanenvironment:

theexperienceof theNododi Bologna construction(ItalianHighSpeedRailway system), ITA-AITES

WorldTunnel Congress 2007 Underground Space the4th Dimension of Metropolises Prague, 510

May, 2007.

GrassoP. & Guglielmetti V., 2008High-speedRailway Underground-CrossingBologna, Italy, Workshopon

Tunnels in densely populated urban areas Professional Association of Civil Engineers of Catalonia

Barcelona, 7April 2008.

25

Underground Infrastructure of Urban Areas Madryas, Przybya & Szot (eds)

2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-48638-5

Numerical analysisof theeffect of compositerepair on

compositepipestructural integrity

A. Bezowski & P. Str zyk

Wrocaw University of Technology, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Wrocaw, Poland

ABSTRACT: Thepaperdealswiththeproblemof assessingthestructural integrityof acomposite

reinforcement used to repair anonpressureseweragepiping systemwith assembly damage. An

analysisof thestraincriteriaappliedtoassessthestructural integrityof polyester-glasscomposites

wascarriedout. Thetechnical aspectsof therepair of thedamagearediscussedandanumerical

model of thepipesectionunder repair ispresented. Thecalculationsmadeindicatethecomposite

repair structural andmaterial solutions potential for further improvements andmeasures which

arelesseffectiveinthisregard.

1 INTRODUCTION

Polymer compositesformedfromglassreinforcedplasticsarecharacterizedby relativelightness

andstiffnessandgoodresistancetoenvironmentactionandcausticsubstances. Polymercomposites

arenowcommonlyusedtobuildall kindsof pipingsystems, suchas:

urban infrastructure networks pressure piping systems for water supply, sewers without

pressure, sewagetreatment plant fittings, etc.;

process plants, includingstoragetanks for petroleumderivatives andcaustics, coolingcircuit

pipingsystems, fluegaspipelinesinpower plants, andsoon.

Theminimumservicelifeof urbaninfrastructurepipingsystemsis50years(EN 1796, 2006),

(EN 14364, 2006). Thelifeof 2030years, 40yearsand1030yearsisassumedrespectively in

thepetrochemical industry, nuclear power plants(LeCourtois, 1995) andchemical-resistanttanks.

Polymercompositesaresusceptibletochemical andphysical ageingandmechanical degradation

(Bollaert & Lemason1999), (Tuttle, 1996) whichadversely affect thematerial properties. As a

result, the composites elasticity modulus and strength during the anticipated service life may

decreaseby as much1060%. Thechanges inthecompositeproperties aregradual but they can

bepredictedonthebasisof acceleratedageingtests(Bezowski, 2005). Long-termtestprocedures

for composites are usually modelled on the tests described in (ASTM D2992, 1991). Tubular

specimens(minimum18pieces) aresubjectedtopressureswhichshouldresult inafailurewithin

10000h(14months). Byextrapolatingthesimpleregressiondeterminedfromthecoordinatesof the

failurepointsonecanestimatethestrength(ASTMD2992, 1996) orstiffness(PN-EN1120, 2000)

and(Farshad& Necola, 2004) of thematerial over itswholeservicelife. Theaboveprocedureis

consideredtobeareliablebutexpensivewayof predictingchangesinthepropertiesof composites.

Irrespectiveof gradual degradation, most of thestructures canbeaccidentally damaged(e.g. by

impacts), whichmayadditionallyreducetheir life.

Discontinuitiesintheprotectivelayers(PL) ontheinner surfaceof pipesandtanksinstructures

exposed to the action of corrosion factors pose a threat to their durability. PL discontinuities

canbetechnological defects or servicedamage. Protectivelayers shouldprotect theglass fibres

constitutingthestructural reinforcement against thecorrosiveeffect of liquidsfillingthesystem.

PL discontinuitiesmaydrasticallyreducethedurabilityof thepipingsystem.

27

2 REPAIRSOF PIPINGSYSTEMS

Repairsoncompositepipes, chemical resistant tanksandsoonarecarriedout inorder toremove:

technological defects,

local damage caused during transport or assembly and by incidental service overloads (e.g.

accidental impacts),

deteriorationinthepropertiesasaresult of long-lastingmaterial degradation.

The descriptions of repairs based on the composite reinforcement technology, found in the

literature, focusonafewapplications:

a. Repairsof chemical-resistant, composite(oftenhigh-risk)processfacilitiesforstoringdangerous

caustic substances, etc. Theprinciples of carrying out such repairs aredescribed in (ASME

RTP-1, 2000). Thecriteriaof qualifying adevicefor repair and thepermissiblerepair range

(limitedto310%of theinner surface) arequitestringent.

b. Therepairof theinnersurfaceof wholesectionsof sewerpipelinesbyproducinganewcomposite

shell insidetheoldwornoutconduit. Mainlypreimpregnatedsleeveshardenedinsidethepipeline

by means of elevated temperatureor UV radiation areused. Theachievement of proper ring

stiffnessof thenewshell canbetherepair effectivenesscriterion.

c. Repairs of steel andcompositepipingwithlocal corrosiondamagecausingleakage, by mak-

ingexternal sealingcompositerings. Chemical andpetrochemical industry process pipelines

arerepairedinthis way. Theprinciples of designing, carryingout andevaluatingarepair are

describedin(ASME PCC-2, 2006). Besidesrepairstohigh-riskpipework, thecodesalsocover

repairstolow-riskpipeworkbutwithitsdiameterlimitedto1000mm. Repairsonleakingplaces

insteel pipelinesarediscussedin(AEA Tech, 2005).

Froman analysis of the standards and publications devoted to piping systemrepairs using

composite-basedtechnologiesthefollowingconclusionsemerge:

Most attentionisdevotedtohigh-riskpipingsystemrepairs.

Thecriteriaof qualifyingdamagefor suchrepairs, definedinthestandards, arequitestringent.

The considered techniques of repairing local damage usually do not take into account the

specificityof pipelineslaiddirectlyintheground.

Theplanningof repairsandtheirrealizationandtechnical acceptanceincludeexpertassessments

of thedamageextent andtheeffectivenessof themeasurestaken.

Theabovementionedpublicationsonrepairsaimtoensurehighprofessionalisminthisregard.

Thisisunderstandablesincemostof therepairsaredoneonchemical resistantcomponentsof high-

risk process plants. Professionalismis essential hereas evidenced by descriptions of dangerous

failuresof unprofessionallyrepairedfacilities(Bezowski, 2004), (Myerset al. 2007).

Thispaperpresentsanumerical analysisof thewayinwhichassemblydamagetoaburiedsewer-

agepipingsystemwithoutpressurewascarriedout, focusingonthecomparisonof thenumerically

calculatedstrainsinselectedpointsof theareasubjectedtorepairswiththecriteriafor dimension-

ingcompositecomponentsusedintheconstructionof variouspipingsystems. Thepossibility of

improvingthematerial-structural solutionusedintherepair isassessed. Thepipelinesectionwith

damagewasmadefromDN1400mmpolyester-glasspipeswithringstiffnessSN=10000N/m

2

.

Thewall thicknesswasabout 34mm. Becauseof theimproper applicationof theforcedamagein

theformof cracks, chipsandspallsappearedinthepipesastheywerebeingshifted. Thedamage

wasanalyzedin(Bezowski & Str zyk, 2008).

3 STRAINCRITERIA OF DIMENSIONINGCOMPOSITES

Thedesignof chemical resistant compositepipingsystemsisbasedontheassumptionthat a0.2