Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Pits, Silos and Other Aspects. A Catalogue of Prehistoric Features in Europe

Încărcat de

Josep Miret i Mestre0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

97 vizualizări16 paginiThis is a summary of "Fosses, sitges i altres coses" by Josep Miret. This book is a catalogue of more than sixty features that can be found in the excavation of prehistoric sites. The book seeks to define elements that enable us to identify the function of the features. This is a multidisciplinary study, combining data from agronomy, ethnography and archaeology.

Titlu original

Pits, silos and other aspects. A catalogue of prehistoric features in Europe

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis is a summary of "Fosses, sitges i altres coses" by Josep Miret. This book is a catalogue of more than sixty features that can be found in the excavation of prehistoric sites. The book seeks to define elements that enable us to identify the function of the features. This is a multidisciplinary study, combining data from agronomy, ethnography and archaeology.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

97 vizualizări16 paginiPits, Silos and Other Aspects. A Catalogue of Prehistoric Features in Europe

Încărcat de

Josep Miret i MestreThis is a summary of "Fosses, sitges i altres coses" by Josep Miret. This book is a catalogue of more than sixty features that can be found in the excavation of prehistoric sites. The book seeks to define elements that enable us to identify the function of the features. This is a multidisciplinary study, combining data from agronomy, ethnography and archaeology.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 16

Summary

PITS, SILOS AND OTHER ASPECTS. A CATALOGUE OF

PREHISTORIC FEATURES IN EUROPE

By Josep Miret i Mestre

This book is a catalogue of more than sixty features that can be found in the

excavation of prehistoric sites. The book seeks to define elements that enable us to

identify the function of the features. This is a multidisciplinary study, combining data

from agronomy, ethnography and archaeology.

We have attempted to enable the function of a pit to be identified as naturally as

possible, by means of the shape, content or other, easily verifiable, characteristics.

Despite my efforts, many of the features continue to be difficult to define or are even

controversial: there are numerous examples of this throughout the book.

Firstly, the features are classified into positive and negative. It is well known that

positive features are created by adding material (sediment, stones, mud), while

negative features are cut into the substrate forming the foundation of the site. At the

same time, positive features will be classified by the type of material of which they are

composed: stone or mud. In contrast, negative features will be classified by their

shape, then by their content or certain specific characteristics (e.g. rubefaction of the

walls).

Some types of feature can be constructed with stone or mud. For this reason, they are

repeated several times in this book.

Constructions

In general, constructions can be classified according to the main material used to build

the walls. This enables us to refer to stone houses, mud houses or wooden houses. If a

mixture of techniques is used, involving the use of different materials, the main

material takes priority. Roofs are nearly always made from vegetable matter (logs,

branches, straw, etc.).

Stone houses. Stone houses can have walls made from dry stone, meaning that no

type of binder is used to join the stones, or the stones can be joined with mud. Houses

with stone walls are found in places where stones are plentiful, such as the

Mediterranean (Fig. 2.3).

2

Mud houses. Different techniques are used in construction with mud: adobe, mud

walls, cob (called bauge in French), and wattle and daub. Houses made from adobe or

mud walls often have a dry stone base to prevent dampness in the floor (Fig. 2.4).

Wooden houses. These houses have walls made of wooden posts driven into the

ground to support the weight of the roof. The walls can be made exclusively of logs,

but it is very common for them to be made with wattle, with warped branches covered

by a layer of mud (wattle and daub). In archaeology, wooden houses are identified by

finding post holes arranged at regular intervals, or foundation trenches with post holes

(Fig. 2.5 and 2.8).

Storehouses and granaries. The granary was a room or building designed to store all

types of grain and pulses. It was used preferably to store large volumes of grain and

pulses in the short and medium term. The granary could take many forms, as it could

be a separate building or a room high up in the house. In this work, we differentiate

between granaries with grain compartments, granaries on posts, granaries on stones

and granaries supported by parallel walls. Chapter 2 of the book provides a description

of each type of granary (2.10-2.12).

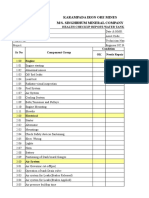

TYPE FORM IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Stone houses Circular, oval, rectangular,

etc.

With stone walls

Mud houses Circular, oval, rectangular,

etc.

With mud walls

Wooden houses Circular, oval, rectangular,

etc.

With walls made from logs

Storehouses and granaries Circular, rectangular Variations:

- On wooden posts

- On stones

- On walls

Table 1.1: Types of feature documented in prehistoric Europe

Positive Features

Stone features

Stone features are usually paved and can correspond to any of the features described

below, in order of size, from the largest to the smallest.

Threshing floors. Threshing floors are places in which grains and pulses were threshed.

They usually consist of spaces with a circular base of large diameter (approximately

fifteen metres in traditional threshing floors). Threshing floors from prehistoric times

have rarely been identified in excavations. However, as there is some paving in

traditional threshing floors, I believe that it is important that they should at least be

mentioned.

Haystacks. Traditional haystacks are piles of straw, usually stacked around a central

post. In some regions, traditional haystacks have an upper section protected by a layer

3

of mud. However, haystacks from prehistoric times have been identified very rarely

(Fig. 6.4).

Stone walls. These are walls made mainly from stones. They can be dry stone (if no

element joins them together) or connected by mud, lime or any other binder.

Benches. A bench is a low wall (typically 0.5 m) attached to another wall, which serves

as a corbel on which to place millstones, large earthenware jars and all types of utensil.

A variation on the bench is the pot holder, which has small hollows into which the base

of the earthenware jars fit. There are also benches and pot holders made from adobe,

as shall be seen below.

Granary bases. These are paved, generally forming a circular shape, to support a

wooden granary. These features are found outside houses and vary in shape and size

(Fig. 2.11).

Above ground silo bases. These are paved in a circular or rectangular shape, and can

be inside or outside houses. Among and on top of the stones (if preserved), there

should be a layer of settled clay and the beginning of the mud walls (Fig. 4.3).

Hearths. Some fires have a hearth made from stone pebbles, the aim of which was to

store the heat of the fire above, releasing it gradually to cook food slowly. These

hearths usually have a circular base and a diameter of around 0.60 m, although they

are also known to be oval and even slightly irregular.

Grain compartments. A grain compartment is a compartment of low height within the

granary or in the room of the house used to store the grain in bulk. It can be made of

stone or mud. The stone grain compartment was created by placing slabs vertically to

define an area. It can also be in the corner of a room (Fig. 3.10, 1).

Millstone supports. Millstone supports consist of a stone or mud feature that fixes the

millstone to the floor, in order to collect the flour or to raise the millstone from the

ground, making it more accessible (Fig. 3.14).

Pot holders. With a circular base of small diameter, these stones supported a large

earthenware jar or a basket. Pot holders can also be negative features, as shall be seen

below (Fig. 5.8).

4

TYPE SHAPE IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Threshing floor Circular Paved area of large diameter

Haystack Circular Large paved area

Stone wall Elongated Aligned stones

Bench Elongated Low wall

Granary base Generally circular Paved

Above ground silo base Circular or rectangular Paved with mud remains

Hearth Circular or square A set of stones or pebbles

Ash and charcoal

Grain compartment Circular or square Slabs placed vertically

Millstone support Circular Paved, and above which is a

hand-operated millstone

Pot holder Circular in plan and of small

diameter

A circle of stones of small

diameter

Table 1.2: Positive stone features

Mud features

There are a significant number of features made from mud, including above ground

silos, grain compartments, ovens, fire hearths, etc. It should be noted that, in some

cases, the same features are repeated as those made with stone. This is because there

are features that can be made from stone or mud. I have described them in order of

size, from the largest to the smallest.

Above ground silos for grain. This is a silo found above ground level. Unanimity does

not exist between archaeologists, ethnographers and agronomists on the difference

between a granary and an above ground silo. The same construction can be described

by one author as a granary and by another as a silo. In the absence of consensus, I

suggested using the word granary for constructions made from wood and vegetable

fibre to store grain, and the word above ground silo for those made from mud and its

derivatives (Miret 2010: 52-53). It should be noted that an above ground clay silo can

have a stone base (see above) (Fig. 4.3).

Benches. As stated previously, this is a low wall attached to another wall, which serves

as a corbel on which to place millstones, large earthenware jars and all types of utensil.

In this case, it is a bench made from adobe.

Domed pottery kilns. The most well known pottery kilns are those with a dome and

double chamber, a fire chamber and a cooking chamber, separated by a grill with

perforations. Sometimes quite well preserved kilns are found, but we often identify

pottery kilns by finding fragments of the grill made from fired mud (Fig. 10.8).

Domed domestic ovens. Domestic ovens (ovens for cooking bread and other food,

found inside houses or in their vicinity) can be divided into domed ovens and ovens

dug into the ground. The first type is a positive feature and the second type is a

negative feature. Domed ovens are constructed with a mesh of branches that support

5

the clay walls in a semi-spherical shape, or as a truncated cone (Fig. 3.5 and 3.6). To

cook bread, a fire is lit inside the oven. When the desired temperature is reached, the

ash and logs are removed, and the bread, or food to be cooked, is placed in the oven.

In an archaeological excavation, the base of ovens is sometimes found, but often only

fragments of mud walls thrown into a waste pit can be identified.

Grain compartments. A grain compartment is a compartment of low height made

from cob or wattle and daub in order to contain grain (Fig. 3.10, 2). A grain

compartment can be located in the corner of a room, used to preserve grain or other

elements. It can have straight walls or a wall curved into one quarter of a circle.

Fire hearths. There are fires with a mud hearth as a base that re-emitted the heat of

the fire lit within. Below, there may be a layer of pottery fragments or pebbles (Fig.

3.1).

TYPE SHAPE IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Above ground silo Circular or square Walls of cob or wattle and

daub

Bench Elongated Low wall

They can have hollow spaces

to support large earthenware

jars

Domed pottery kiln Circular or square Two chambers separated by a

fired-mud grill

Fired-mud walls

Domed domestic kiln Circular Hearth made from mud and

stones

Fired-mud walls

Grain compartment Circular or square Low mud walls

In a house or granary

Fire hearth Circular or square Hearth made from mud

Charcoal and ash

Table 1.3: Positive mud features

Negative Features

The pits or negative features have already been described above. I now wish to

indicate simply that negative features can be deep or shallow. Firstly, we will address

the deep features, the depth of which is greater than the width. We will see that they

can be classified according to whether they are circular, rectangular, oval or elongated

in plan. Further on, we will discuss shallow features, special-shaped features (usually

industrial pits designed to obtain a particular product) and those with a non-specific

shape, defined by the objects found inside.

6

Deep features that are circular in plan

We will begin by discussing the deep negative features, and, within this category,

those that are circular in plan. They are ordered by diameter, from the largest to the

smallest.

Underground silos for grain. These are considered the most common type of pit in

prehistoric settlements in Europe, except on sites with wooden houses, where the

most common feature is the post hole. In terms of shape, the analysis of reference

works from the fields of agronomy, ethnography and archaeology shows that silos for

storing grain are the only underground features that are truncated cone-shaped, egg-

shaped or bottle-shaped (Fig. 4.1). Cylindrical silos are also normal, but this shape is

shared by many other types of pit, which makes it necessary to seek other elements to

correctly identify a silo for grain. Other criteria that enable a silo to be identified are: 1)

A carpological analysis of the sediment in the bottom of the silo, in which grain

appears. 2) A mud coating on the walls in order to improve waterproofing. 3) A slight

rubefaction of the walls, caused by burning waste from a previous silo. 4) The presence

of circular stone slabs or lids made from mud, etc.

Storage pits with intact pottery. Storage pits with intact pottery are storage pits for

grain, which, when empty (usually in the summer), were used to preserve food in

pottery. They are identified by the presence of intact pottery in the bottom of the

storage pit. The pottery should preferably be large earthenware storage jars. This is a

key element that differentiates them from domestic cache pits and ritual pits (Fig. 5.6

and 5.7).

Semi-underground silos for cereal grains. In semi-underground silos, the grain is found

partly underground and partly above ground. In ethnography, these are not very

common, and, in archaeology, it should be noted that they are difficult to identify

because the base that remains is a basin or a shallow cylindrical pit, which is difficult to

distinguish from other types of pit (Fig. 4.2).

Root storage pits. Root storage pits are found in other latitudes. In Europe, they have

not been documented for certain until the end of the Middle Ages (Fig. 5.2).

Silage pits. Silage pits did not become widespread until the 19

th

century, although

some authors believe that they may have been used in the Iron Age (Fig. 5.3).

Wells. A well is a cylinder of significant depth that extends from the old surface of the

ground to the water table, where water is found. The depth is nearly always greater

than 2 or 3 m, and there are cases of Neolithic wells of up to 15 m. Those of a later

date can be even deeper. The lower section generally consists of walls covered with

logs or dry stone walls. Central European prehistorians differentiate between different

types of well: Kastenbrunnen, Rhrenbrunnen, wickerwork, etc. depending on the

structure that prevents the walls from collapsing (Figs. 3.11 and 3.12).

Sandy bed pits. This was a rare type of feature in prehistoric times (I do not know of

any definite example), but it is well described by ancient agronomists and in

7

ethnography. They are cylindrical or cubic pits with a layer of sand in the bottom. Food

(fruit, roots, nuts, etc.) was placed inside to be preserved (Fig. 5.4).

Vats. These are cylindrical pits covered with a skin and used to contain liquid such as

whey. I do not know of any prehistoric examples in Europe and only have information

from ethno-archaeology (Fig. 5.12).

Fermentation pits. These are pits coated in leaves in which fruit and roots were

fermented, enabling the products to be preserved for longer. They are used, above all,

in tropical areas and are unknown in Europe (Fig. 5.13).

Storage pits for nuts. The few storage pits for nuts found from prehistoric times are

cylindrical and have smaller dimensions than silos for grain. Ethnographical examples

that are rectangular in plan are also known. In archaeology, storage pits for nuts are

identified by finding the remains of nuts (generally charred) inside a cylindrical pit (Fig.

5.1).

Storage jars buried to the neck. These are large earthenware jars buried to the neck in

cylindrical pits, usually with a concave base adjusted to the shape of the jar. Storage

jars buried to the neck contained liquids such as wine, oil or water. According to

ethnographical data, they could also preserve some types of fruit (Figs. 5.9 and 5.10).

Underground mortars. This type of mortar consisted of a simple pit made in the

ground, in which seeds were placed in order to crush them using a stick or a wooden

mallet. Underground mortars were of modest size, with a diameter of 0.30m or 0.40m,

and a similar depth (Fig. 3.13).

Post holes. This type of feature enables wooden houses to be identified. It consists of a

cylinder of small diameter with a depth several times greater than its diameter. It

could also be used as the foundation of a palisade or for other features such as

bridges, haystack posts, etc. (Fig. 2.9)

Deep features that are rectangular or oval in plan

There are few negative features that are rectangular in plan. Wells, silos (of all types),

pit houses and even some semi-underground granaries can be rectangular. When we

find a pit that is rectangular in plan in the excavation of a feature from prehistoric

times, we should assume, in principle, that it is a storage cellar.

Storage cellars. Prehistoric storage cellars are pits that are rectangular or oval in plan,

although storage cellars are also known to be in the shape of a passageway with stone

walls. Storage cellars were used to preserve all types of food. The food could be placed

in storage cellars in pottery, barrels, boxes, sacks, or it could be stored hanging, etc.

The preservation of food in storage cellars was based on the greater stability of below

ground temperatures, especially with the coolness underground during the summer

months (Fig. 5.5).

On some sites, storage cellars are known to have had a wooden box to prevent the

food coming into contact with the walls of the pit.

8

Deep features that are elongated in plan

Pits that are elongated in plan can be classified in many ways. Here I have outlined the

types of pit related to settlements first, followed by the agrarian and natural features.

Storage cellars. As described above, storage cellars exist that are in the shape of a

walled passageway (Fig. 5.5, 3).

Foundation trenches. These trenches are the foundation of dry stone walls or walls

made from supporting logs. If connected to post holes, these foundation trenches

enable us to identify wooden houses.

Fences and palisades. Fences and palisades are detected by the alignment of small

post holes or foundation trenches narrower than those of a wall. Fences could be for

livestock or to define a settlement. Palisades could be for defence purposes when they

are connected to ditches.

Ditches. These usually define settlements. They are connected to palisades and their

purpose is usually attributed to defence. Neolithic ditches are often discontinuous and

arranged one after the other (Fig. 2.16).

Ard marks or plough lines. These are the marks left by the plough in the substrate of a

crop field. They are small parallel trenches arranged along the fields, and often cross-

sectioned by other orthogonal marks. Modern ploughs usually erase the markings left

by older ploughs. As a result, many plough markings that have been preserved are

under prehistoric mounds that seal older crop fields (Fig. 6.1).

Plot boundaries. These are trenches that define an old crop field. They are often found

as a result of aerial photography or laser altimetry, enabling the identification of land

that used to be divided into plots. Land divided into plots in prehistoric times, usually

known by the name of Celtic fields, has been found in several regions in temperate

Europe.

Drainage channels. These are trenches that collect water from a settlement or a

cultivated plot of land, and direct it towards a river or stream. They can be identified

by aerial photography or directly through excavation.

Paleochannels. These are channels along which rainwater used to pass, and which

have been covered by agricultural terraces. They are not anthropic features, but

natural elements. They are included in this work because they can be found in an

archaeological excavation (Fig. 11.2).

TYPE SHAPE IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Underground silo for grain Cylindrical, truncated-cone

shaped, egg-shaped or bottle-

shaped

Charred grain

Coating of the walls with clay

Slight rubefaction of walls

Grain imprints

Presence of lids

Storage pit with intact pottery Cylindrical, truncated-cone

shaped, egg-shaped or bottle-

shaped

Intact storage pottery

Semi-underground silo for Cylindrical basin Charred cereal grains

9

grain

Root storage pit Cylindrical

Silage pit Cylindrical or elongated

Well Cylindrical Great depth, to the water table

Protective elements in the

lower section (logs, stone

walls)

Sandy bed pit Circular or square in plan Layer of sand or ash in the

bottom

Vat Cylindrical

Fermentation pit Cylindrical

Storage pit for nuts Cylindrical Charred nuts

Storage jar buried to the neck Cylindrical and concave in

plan

Relatively intact preserved

storage jar (more than half the

jar)

Underground mortar Cylindrical Small dimensions

Layer of clay on the walls

Post hole Cylindrical, narrow and deep Sediment with charcoal or

organic matter (dark

colouring)

Wedging stones

Storage cellar Rectangular, oval or

elongated in plan

The storage jars it contained

can be preserved

They can have a wooden box

Foundation trench Elongated Connected to a wall

Fence or palisade Elongated Line of post holes or

foundation trenches defining

an area

They can be connected to a

pit

Ditch Elongated They usually define a dwelling

area

They can be connected to a

palisade

Ard mark or plough line Elongated Small channels following the

direction of the long side of a

field or cross-sectioned

Plot boundary Elongated They are usually in a straight

line and define a rectangular

field

Drainage channel Elongated They can be in a dwelling

area or define crop fields

Paleochannel Elongated Former streambed created by

nature

Table 1.4: Deep, negative features, which are greater in depth than width

10

Shallow features

Continuing with negative features, this section outlines some regular features

characterised for their shallowness. They are ranked from largest to smallest.

Pools. These are large hollows, usually near settlements, in which rainwater

accumulated. Layers of clay and silt swept along by the water are detected at the

bottom of the pool. A sediment study can reveal diatom skeletons and other

organisms belonging in stagnant water. Pottery is sometimes found in the bottom of

pools. It is assumed that these were used to collect water and were lost.

Pit houses. This is a classical type of feature and is quite controversial. It is a house in

which the floor is a regular-shaped pit. In some cases, it can be an entire dwelling, but

European examples from prehistoric times are more likely to point to a specific

purpose: a workshop, livestock enclosure, storehouse, etc. Until the 1980s, a pit

house was the name given to any negative feature (Figs. 2.13-2.15).

Earth ovens. These are also called cooking pits. They are a special type of oven

consisting of a circular or elongated pit in which food was cooked by adding very hot

stones taken from a fire located nearby or in the same pit. Food was wrapped in leaves

and cooked slowly. Ethnographical studies indicate that earth ovens were used above

all for feasts and banquets, as they were ovens that enabled an entire animal to be

cooked, and, and were, therefore, not suitable for cooking the small quantities of food

required on a daily basis (Figs. 3.7-3.9).

Fire pits. Fires were sometimes constructed in basins, which served to concentrate the

heat of the fire on the container being used for cooking. Fire pits are identified when a

basin is found with rubefaction of the walls, and the interior is full of ash and charcoal

(Fig. 3.2 and 3.3).

Pot holders. This is a small hollow with a flat or concave base that was used to hold a

large earthenware jar. Sand or wedging stones were sometimes used to adjust the

base of the earthenware jar to the shape of the pit (Fig. 5.8, 2).

11

TYPE SHAPE IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Pool These tend to be circular with

a large diameter

They can have a supply

channel bringing water

Silt in the bottom of the pool

Pit house Circular or rectangular Flat ground

They can have domestic

features such as fires, ovens,

grain compartments, etc.

Earth oven (cooking pit) Circular or elongated

rectangle

Heat-altered stones

They can have large pieces of

charcoal

Fire pit Circular Rubefaction of walls

Charcoal and ash

Pot holder Circular with a concave base Base of a storage jar in situ

Wedging stone

Table 1.5: Shallow negative features

Special-shaped features

These pits are identified by their different shapes, as they can be cylindrical, funnel-

shaped, elongated, etc. Many of these pits are industrial, meaning that they were used

to make a specific product. In some industrial features, the presence of the product

obtained, or its waste, can be detected. Fire was often used to obtain these products,

in which case we detect charcoal, ash and rubefaction.

Underground domestic ovens. This type of domestic oven is found when the chamber

of an oven is dug into the side wall of a pit house. The majority of examples known in

Europe are from the Middle Ages, but some older ones exist. They are usually circular

in plan and the walls form a dome (Fig. 3.4).

Clay pits. These pits appear irregular, but, when observed in detail, are a combination

of several oval pits. Each oval pit represents an operator who extracted the

surrounding earth (usually an arms length, typically with a maximum axis of 1.5-2 m),

which is vertical directly in front of the operator and less vertical behind, and through

which the sediment was removed. The pits intersect one another, and the ground

evokes the craters of the moon. Until the 1980s, the majority of these pits were

classified as pit houses (Figs. 10.1-10.4).

Pits to settle and knead clay. These are usually clay pits that were reused to settle or

knead the mud that was used in the construction of nearby features and buildings.

Underground pottery kilns. Pottery vessels could be fired in underground pottery

kilns. Ethnography and experimental archaeology show us numerous possible shapes

for these ovens, from cylindrical (basin-shaped) to those with an access shaft and a

cooking chamber dug into the ground (Fig. 10.7).

12

Pottery dumps. In a potters workshop, these are places where badly-fired or

deformed pottery was thrown away. It can be simply a pile or a pit. It is a former clay

pit. The name sensu lato is also given to a build-up of pottery (Fig. 10.9).

Buried storage jars. This is a very special type of feature, to the extent that I do not

know of any definite examples in prehistoric Europe. The definition is based on former

agronomy treatises, which stated that fruit and nuts could be preserved in

hermetically sealed storage jars that were buried in a dry place (Fig. 5.11).

Charcoal piles. This feature was where the charcoal required for metallurgical furnaces

was obtained. It is, therefore, believed that they were developed above all from the

Eneolithic period onwards, although the first charcoal piles identified for certain were

from the Iron Age. The ethnography and history of the techniques demonstrate

different ways of making charcoal, as it could be made in piles or in pits. A charcoal pile

is detected by the presence of charcoal from numerous species suitable for producing

charcoal, such as oak, holm oak, beech, pine, heather, etc. in the Mediterranean

region, or alder, linden, maple or elm in temperate Europe (Figs. 10.15 and 10.16).

Copper furnaces. There are many types. It is necessary to distinguish between

reducing furnaces, which obtained copper from the mineral and are located in mining

areas and smelting furnaces, found on the sites of bronzesmith workshops, and

located near centres of commerce. The most well known reducing furnaces consist of a

quadrangular pit in a sloping location, with stone walls. The inside is full of charcoal

and copper slag. Reducing furnaces consist of a crucible placed on a pit where charcoal

was burned with great intensity, with the help of the airflow provided by bellows

attached to a nozzle. The elements for the identification of a reducing furnace are the

crucible, the pit, the nozzle and the presence of metal slag (Figs. 10.10 and 10.11).

Furnaces. As with copper furnaces, it is necessary to differentiate, on one hand,

between those used to obtain iron from the mineral (reducing furnace) and smelting

furnaces or forges, which are found on the site of blacksmith workshops. In a reducing

furnace, an iron sponge is obtained. This is reheated in the oven and hammered

repeatedly to shape the iron object. An anvil usually appears near the forge, which is a

stone on which the blacksmith hammered the iron (Figs. 10.12-10.14).

Lime kilns. Poorly documented for prehistoric times, these are known above all as a

result of experiments, and, predominantly, due to ethnographic information and

information from ancient agronomists (Fig. 10.17).

Tar kilns. We do not know either of any tar kilns that have been identified and studied.

Nearly all the information available is based on experiments and more recent ovens

(Figs. 10.18-10.21).

Tannery pits. These long, narrow pits are problematic. They are called Schlitzgruben in

German. They used to be considered as pits for tanning skins, which were immersed in

liquid containing tannins. However, they now tend to be interpreted as pit traps.

13

Smudge pits. These are small pits in which matter was burnt to create a significant

amount of smoke that was used to smoke skins. Although this type of pit is well known

in North America, I know of no examples in Europe (Fig. 10.22).

Pit traps. This type of pit is controversial, as it includes the Schlitzgruben, a specific

type of pit found in many places in Europe, which is elongated, deep and very often

has a hollow base. Years ago, this type of pit was considered to be a tannery pit, but it

now tends to be considered a pit trap (Figs. 10.23 and 10.24).

Planting pits. These pits were made in the ground of old crop fields, which were used

to plant vines or other trees. Vines were planted in rows, maintaining a certain

distance between them, in order to facilitate use of the plough. The majority of

planting pits and trenches known are from Roman times, but some are from the Iron

Age and a few older ones exist on Mediterranean islands (Fig. 6.3).

Tree throws. These are irregular pits caused by a tree falling due to the force of the

wind. When the tree falls, the roots are stretched and a rather irregular section of

earth is created in the shape of a D. These pits were caused by nature, but were

occasionally used by people (Fig. 11.1).

TYPE SHAPE IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Underground domestic oven Circular in plan with an access

shaft

Intense rubefaction

Clay pit Pit formed by the combination

of different oval pits that are

juxtaposed

The substrate must be made

of clay

Pit to settle and knead clay A clay pit is usually reused They usually contain clay

settled in the bottom of the pit

Underground pottery kiln Cylindrical Slight rubefaction

Pottery dump A pre-existing pit is usually

used

Build-up of badly-fired or

deformed pottery

Buried storage jar Formed by the combination of

different pits juxtaposed, of

more modest measurements

than clay pits

Charcoal pile Circular or quadrangular in

plan

Charcoal from species

suitable for producing

charcoal

They can be found on the site

of a blacksmiths workshop or

at a distance from settlements

Copper furnace Circular or quadrangular in

plan

Rubefaction of walls

Charcoal

Nozzles

Crucibles

Copper slag

Furnace Circular or quadrangular in

plan

Rubefaction of walls

Charcoal

Nozzles

14

Crucibles

Iron slag

Lime kiln Cylindrical Rubefaction of walls

Lime remains

Proximity to a pool in order to

slake the lime

Tar kiln Funnel-shaped (and other

shapes)

Rubefaction of walls

Charcoal

Tannery pit Long and narrow in a Y V or

W shape

The accumulation of organic

matter, phosphorus, nitrogen,

etc.

Smudge pit Cylindrical with a concave

base

The presence of charcoal that

produced a great deal of

smoke

A layer of smoke in the walls

Pit trap Long and narrow in a Y V or

W shape

Far from settlements

They appear in groups

Planting pit Pits located at regular

intervals

They are identified when

stripping away great layers

Tree throw D-shaped Irregular walls

Table 1.6: Special-shaped features

Non-specific shaped features

For these features, the shape of the pit is unimportant, as it is characterised by the

objects contained within. Advantage is sometimes taken of pits with other functions,

such as silos, post holes, clay pits, etc.

Cache pits. Cache pits are pits, or sometimes simply places (loci), in which a more or

less significant number of tools, utensils and goods are found. They are assumed to

have been hidden underground because they were not required at the time, or

perhaps due to a situation of insecurity, which made it advisable to hide valuable

goods. In a previous work, I classified cache pits into domestic cache pits (Figs. 8.1-8.3),

distribution cache pits (Figs. 7.4 and 7.5) and hoards (Figs. 7.6) (Table 1.7) (Miret 2010:

117-119).

Ritual pits. Ritual pits are pits containing elements attributed to magical-religious

rituals or identified as offerings to divinities. There are many types of ritual pit, and

they are, generally, quite controversial. To avoid excessive digression into a type of

feature that is subject to speculation, I have opted to use the little knowledge we have

from the classical era, for which we know some religious aspects, and to go back in

time to see whether what we find from prehistoric times can be adapted to the

archaeological records from the classical era. In this way, I have taken the following

types of ritual pit into consideration (Table 1.7): foundation depots (Figs. 8.1-8.3), ritual

pits with animal bones in anatomical connection (Fig. 8.4-8.5), ritual pits with

15

banqueting remains, ritual pits related to libation (Figs. 8.6-8.8), ritual pits with objects

of worship, and findings in swamps. These features are described in greater detail in

chapter 8.

Burial pits. The number of prehistoric features and constructions related to death is

very extensive: passage graves, cists, barrows, urnfields, hypogea, grave pits, etc. This

monograph studies only a few burial features: storage pits for grain reused as a burial

place, animal graves in tombs or cemeteries, etc. (Figs. 9.1-9.2).

Waste pits. Based on the ethno-archaeological works of Hayden and Cannon (1983), it

is necessary to distinguish between two types of waste pit. The authors mentioned

maintain that waste was sorted twice. Firstly, there was a provisional discard, in which

the remains of food or ash were thrown into a temporary dump (such as a manure

heap), broken pottery was stored in case it could be used to give water to animals or

to protect vegetable garden plants, etc. Sometimes, usually once a year, a final discard

was made. The content of the manure heap was poured onto crop fields, and objects

that could not be used were thrown into any type of pit that had lost its original use.

This could be a silo, clay pit, well, etc., or the bed of a stream.

TYPE SHAPE IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS

Cache pit or domestic cache

pits

A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Many types of pottery, tools,

millstones, raw materials.

Found within settlements

Cache pit or distribution cache

pits

A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Repeated series of bronze,

stone axes or flint tools.

Smelter deposits with broken

objects.

Distanced from settlements

Hoard A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Necklaces, bronze tools, coins

Belonging to historical times

Foundation depot In a post hole, a trench or a pit

covered by the paving of a

house

They can contain intact

pottery, the skeleton of a

sacrificed animal or coins

Ritual pit with animal bones in

anatomical connection

A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Full or partial skeleton of a

sacrificed animal.

Found within a settlement or

place of worship

Ritual pit with banqueting

remains

A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Remains of exceptional types

of food (unusual species).

Found within places of

worship or burial areas

Ritual pit related to libation A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Series of cups for individual

use (glasses, dishes)

Ritual pit with objects of

worship

A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

Deposit of objects of worship

(pots, figurines, miniature

vessels, etc.)

Findings in swamps Objects of all types thrown

16

into swamps or buried in

surrounding areas

Burial pit (in a settlement) A pre-existing pit is usually

reused, generally a silo

Graves in silos, under houses,

etc.

They can be primary or

secondary

Waste pit A pre-existing pit is usually

reused

All types of waste and rubbish

Table 1.7: Non-specific shaped features, characterised by their content

English translation: Victoria Pounce

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Electric Vehicles PresentationDocument10 paginiElectric Vehicles PresentationVIBHU CHANDRANSH BHANOT100% (1)

- Geometry and IntuitionDocument9 paginiGeometry and IntuitionHollyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Microeconomics Term 1 SlidesDocument494 paginiMicroeconomics Term 1 SlidesSidra BhattiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dehn Brian Intonation SolutionsDocument76 paginiDehn Brian Intonation SolutionsEthan NealÎncă nu există evaluări

- DIFFERENTIATING PERFORMANCE TASK FOR DIVERSE LEARNERS (Script)Document2 paginiDIFFERENTIATING PERFORMANCE TASK FOR DIVERSE LEARNERS (Script)Laurice Carmel AgsoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ac221 and Ac211 CourseoutlineDocument10 paginiAc221 and Ac211 CourseoutlineLouis Maps MapangaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vernacular ArchitectureDocument4 paginiVernacular ArchitectureSakthiPriya NacchinarkiniyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- TMPRO CASABE 1318 Ecopetrol Full ReportDocument55 paginiTMPRO CASABE 1318 Ecopetrol Full ReportDiego CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japanese GardensDocument22 paginiJapanese GardensAnmol ChughÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agile ModelingDocument15 paginiAgile Modelingprasad19845Încă nu există evaluări

- Audi R8 Advert Analysis by Masum Ahmed 10PDocument2 paginiAudi R8 Advert Analysis by Masum Ahmed 10PMasum95Încă nu există evaluări

- Acampamento 2010Document47 paginiAcampamento 2010Salete MendezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Tanker Check ListDocument8 paginiWater Tanker Check ListHariyanto oknesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Review of Stories Untold in Modular Distance Learning: A PhenomenologyDocument8 paginiA Review of Stories Untold in Modular Distance Learning: A PhenomenologyPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avid Final ProjectDocument2 paginiAvid Final Projectapi-286463817Încă nu există evaluări

- AFAR - 07 - New Version No AnswerDocument7 paginiAFAR - 07 - New Version No AnswerjonasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ds-Module 5 Lecture NotesDocument12 paginiDs-Module 5 Lecture NotesLeela Krishna MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oral ComDocument2 paginiOral ComChristian OwlzÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 - A Note On Introduction To E-Commerce - 9march2011Document12 pagini01 - A Note On Introduction To E-Commerce - 9march2011engr_amirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optimal Dispatch of Generation: Prepared To Dr. Emaad SedeekDocument7 paginiOptimal Dispatch of Generation: Prepared To Dr. Emaad SedeekAhmedRaafatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toi Su20 Sat Epep ProposalDocument7 paginiToi Su20 Sat Epep ProposalTalha SiddiquiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3rd Page 5Document1 pagină3rd Page 5api-282737728Încă nu există evaluări

- UnixDocument251 paginiUnixAnkush AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Footing - f1 - f2 - Da RC StructureDocument42 paginiFooting - f1 - f2 - Da RC StructureFrederickV.VelascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture Notes 3A - Basic Concepts of Crystal Structure 2019Document19 paginiLecture Notes 3A - Basic Concepts of Crystal Structure 2019Lena BacaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- P. E. and Health ReportDocument20 paginiP. E. and Health ReportLESSLY ABRENCILLOÎncă nu există evaluări

- N2 V Operare ManualDocument370 paginiN2 V Operare Manualramiro0001Încă nu există evaluări

- ThaneDocument2 paginiThaneAkansha KhaitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Projects PDFDocument1 paginăCourse Projects PDFsanjog kshetriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation Municipal Appraisal CommitteeDocument3 paginiPresentation Municipal Appraisal CommitteeEdwin JavateÎncă nu există evaluări