Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Academic Research in Rehab

Încărcat de

Alexandra Nadinne0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

16 vizualizări7 paginiAcademic research in rehab

Titlu original

Academic research in rehab

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentAcademic research in rehab

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

16 vizualizări7 paginiAcademic Research in Rehab

Încărcat de

Alexandra NadinneAcademic research in rehab

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 7

STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access

Study protocol: Improving patient choice in

treating low back pain (IMPACT - LBP): A

randomised controlled trial of a decision support

package for use in physical therapy

Shilpa Patel

1*

, Sally Brown

2

, Tim Friede

3

, Frances Griffiths

4

, Joanne Lord

5

, Anne Ngunjiri

1

, Jill Thistlethwaite

6

,

Colin Tysall

2

, Mark Woolvine

7

, Martin Underwood

1

Abstract

Background: Low back pain is a common and costly condition. There are several treatment options for people

suffering from back pain, but there are few data on how to improve patients treatment choices. This study will

test the effects of a decision support package (DSP), designed to help patients seeking care for back pain to make

better, more informed choices about their treatment within a physiotherapy department. The package will be

designed to assist both therapist and patient.

Methods/Design: Firstly, in collaboration with physiotherapists, patients and experts in the field of decision

support and decision aids, we will develop the DSP. The work will include: a literature and evidence review;

secondary analysis of existing qualitative data; exploration of patients perspectives through focus groups and

exploration of experts perspectives using a nominal group technique and a Delphi study.

Secondly, we will carry out a pilot single centre randomised controlled trial within NHS Coventry Community

Physiotherapy. We will randomise physiotherapists to receive either training for the DSP or not. We will randomly

allocate patients seeking treatment for non specific low back pain to either a physiotherapist trained in decision

support or to receive usual care. Our primary outcome measure will be patient satisfaction with treatment at three

month follow-up. We will also estimate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention, and assess the value of

conducting further research.

Discussion: Informed shared decision-making should be an important part of any clinical consultation, particularly

when there are several treatments, which potentially have moderate effects. The results of this pilot will help us

determine the benefits of improving the decision-making process in clinical practice on patient satisfaction.

Trial registration: Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN46035546

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a common, disabling and expen-

sive disorder. In 1998 treating this condition cost the

National Health Service (NHS) 1,632M [1]. The 2009

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

(NICE) guidelines for early management of persistent

non-specific LBP [2] recommend that clinicians consider

offering patients with chronic LBP a course of one of a

range of different therapies (acupuncture, exercise, man-

ual therapy), depending on the patients preference.

These therapies have modest average benefits at a mod-

est cost. The clinical effects and the costs of these differ-

ent treatments are of a similar magnitude, so there is no

clear basis for preferring any one of these treatments for

use in the NHS. It is, however, possible that improved

matching of patients to treatments will produce a

greater overall positive effect. An understanding of the

factors that inform patient choice and decision-making

* Correspondence: shilpa.patel@warwick.ac.uk

1

University of Warwick, Clinical Trials Unit, Warwick Medical School, Gibbet

Hill Road, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

2011 Patel et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

might help patients to make the best treatment decision

for themselves. Having the opportunity to participate in

such decision-making may also be associated with better

health outcomes [3,4].

A patient-centred approach, using shared decision-

making (SDM), involves the patient and healthcare pro-

fessional discussing treatment options and interacting to

agree on a management plan [5,6]. This approach is

widely advocated but its use in practice is challenging

[7]. SDM involves taking patient expectations, prefer-

ences, concerns, ideas and values, plus the practitioners

values and experiences into account. In contrast,

informed decision-making involves presenting patients

with relevant information and options without the

healthcare professional expressing a preference. This

informed model gives patients autonomy but fails to

take into account the shared interaction [8]. The

patient-practitioner interaction model represents

informed shared decision-making (ISDM) and is the

model that will be used to design a decision support

package (DSP) for LBP patients. The quality of patient-

practitioner interactions may be crucially important in

improving back pain outcomes [9].

Coaching to support patients making decisions is

effective in aiding patients knowledge, information

recall, and participation in decision-making [10]. Deci-

sion aids are interventions designed to help people

make specific and deliberate choices among options by

providing information about the options and outcomes

relevant to a persons health status [10]. These aids pro-

vide information to facilitate patients involvement in

the decision-making process. Patient expectations and

preferences also play a role in decision-making and may

affect outcomes. Patients with a higher expectation of

recovery have reported higher functional improvement

[11]. Within randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in gen-

eral, those randomised to their preferred treatment gain

more benefit [12]. However, evidence from RCTs of

LBP is equivocal: one RCT of LBP found that those who

expected better outcomes with treatment gained more

benefit than those who did not; however another trial

failed to show that expectations affected outcome

[13,14]. Patient preferences may also affect treatment

adherence [15].

Patients report they would like to play an active role

in decisions concerning their health [16]. Many patients

also want a patient-centred approach to decision-making

incorporating communication, partnership and health

promotion [17]. However it is important to remember

that while not all patients want to be involved in deci-

sion-making all of the time, they should be given choice

about the depth of involvement. Clinicians do not

always involve patients in decision-making; possibly

because they feel ill trained to do so [18]. Despite this,

general practitioners (GPs) have positive views about

SDM and can gain the skills required to implement

SDM in practice [19,20].

The aim of this pilot RCT is to develop and test the

effect of a DSP on patient satisfaction. This package will

comprise material to assist both the physiotherapist and

patient during the informed shared decision-making

process. Overall, the DSP will be designed to help

patients seeking care for back pain, make informed

choices, about their treatment which are the best for

them.

Methods/Design

This pilot has been funded by the National Institute of

Health Research - Research for Patient Benefit Pro-

gramme (Ref: PB-PG-0808-17039). Ethical approval has

been granted by Warwickshire Research Ethics Commit-

tee (Ref: 10/H1211/2).

Intervention design

To inform the design of the DSP, we will conduct a series

of exploratory studies (described in more detail below).

This work will be carried out in collaboration with phy-

siotherapists, patients, and experts in the field of decision

support and decision aids. At this time it is difficult to

predict the exact nature of the DSP - this will depend on

the findings from our exploratory work. However, we

anticipate that there will be: an information package that

summarises the nature of each intervention; a rationale

for the interventions, questions that assist the patient in

reviewing their current health status and the value they

place on possible future scenarios, and what is known

about the effectiveness of the interventions.

In a recent Cochrane review of decision aids for peo-

ple facing health treatment or screening decisions, the

included studies used a variety of decision aids for a

range of conditions. A sample of some of the decision

aids included were cancer treatments and screening,

back surgery, hormone replacement therapy and osteo-

porosis treatments. The decision aids varied in formats

including video tapes, computer based interactive pro-

grammes, audio material and information booklets [21].

Some decision aids were available in a combination of

formats giving patients options. Our DSP will be

designed to enable easy implementation into routine

NHS care. This will be suitable for use by both patients

and therapists. We anticipate that once this package has

been developed, we will devise a formal training pro-

gramme to deliver to physiotherapists to improve their

knowledge of the treatment options and their skills in

ISDM. We will integrate patients and therapists views

on the content and format of our decision support pack-

age. We will subsequently publish a paper describing the

intervention in detail.

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

Page 2 of 7

In the early phase, we will ask physiotherapists within

the Coventry Community Physiotherapy team to test

the intervention in an uncontrolled manner, allowing us

to test practicality and feasibility in the clinical environ-

ment. We will assess this by direct observation of the

consultation process and through focus groups with

patients and physiotherapists. This will allow us to opti-

mise the intervention before starting the pilot RCT.

The section below describes the exploratory work to

be undertaken to inform the intervention design.

A. Literature & evidence review

We will review relevant new trial data published since the

2009 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

(NICE) guidelines on low back pain [2]. This will allow us

to identify any new data that, if available to the guideline

development group, may have led to a change of recom-

mendations. We will only include RCTs of therapist deliv-

ered interventions with a sample size >349. This is the

sample size beyond which an RCT can detect a standar-

dised effect size of 0.3 or less with 80% power and 5% sig-

nificance if there are two groups split evenly [22]. It is

such large trials that might, in the future, lead to changes

in guidance. The information about the treatments and

evidence in our DSP will be based on this NICE guidance

and subsequent trials identified from this review.

We will systematically seek studies of decision aids for

treatments for benign disorders, such as tennis elbow or

depression, with multiple moderately effective treatment

options. We will extract data about the components of

these interventions and the mechanisms by which they

are thought to act. We will use this data to inform the

design of our decision aid.

We will also systematically identify qualitative studies

of people with chronic back pain that include accounts

of why they chose different therapies. This will provide

us with some understanding of the reasoning behind

treatment choice within patients with back pain.

B. Secondary Analysis

We have interview data from people living with back

pain undertaken with individuals in both the interven-

tion and control arm of a clinical trial evaluating a

group cognitive behavioural approach for patients with

low back pain in primary care (Back Skills Training

Trial - BeST) [23]. Interviews were undertaken at 2-4

months after the intervention (or baseline assessment)

and 12 months later. The interviews include exploration

of the experience of living with back pain including the

use of interventions beyond that being evaluated in the

trial. We will re-analyse these data to identify influences

on treatment decisions and use this data in our decision

aid planning and development.

C. Patients perspectives

Concurrently we will develop a questionnaire to mea-

sure current patient preferences for treatment. We will

approach around 100 people seeking treatment from the

physiotherapy department for LBP. Those interested will

be asked to complete the questionnaire and subse-

quently participate in a focus group. Interested respon-

dents will provide a sampling frame for our focus

groups. Our purposive sampling willbe informed by age,

gender, duration & troublesomeness of LBP, treatment

decisions and treatment preferences. We will run two

focus groups to develop a broad understanding of the

factors that inform choice and decision-making among

patients with back pain in which we will explore: how

patients make decisions in general (i.e. decision style),

how they make decisions and choices about treatments

for their back pain, what information patients would

like to help them make more informed choices, and

what patients think of the existing material on offer to

them.

Qualitative data will be analysed using the framework

method to identify key concepts and themes [24].

D. Experts perspectives

To develop an understanding of experts views and

experiences of informed shared decision-making for LBP

treatments we have selected two broad areas of experts,

physiotherapists and patient experts. By engaging these

two groups we hope to generate a range of experiences

which will feed into our intervention design.

We will recruit physiotherapists, who regularly provide

first contact care for low back pain from a neighbouring

primary care trust, to a nominal group - a formal face

to face consensus method [25]. This is a structured

approach to data collection from a group who have

insight into a specific topic area. This method allows

ideas to be generated as well as solutions to be achieved.

Participants are initially asked to generate ideas, which

the group later discuss and rank in order of importance.

We have selected this method as it encourages partici-

pation from everyone and as a result we hope it will

lead to good quality ideas and solutions.

Concurrently, we will also conduct a Delphi study

with patient group leaders, expert patients and advocacy

group activists. We will work with local and national

organisations to identify expert patients who have

experience of managing back pain. We have selected the

Delphi method as it is a practical method of obtaining

opinions from a range of experts nationally. We will

develop a set of questions to send to the experts; the

responses will then be collated and fed back to the par-

ticipants for further rounds of questions. Rounds will

continue until consensus is achieved.

The results of the reviews and secondary analyses

together with the focus groups, nominal group techni-

que and the Delphi study will feed into the intervention

design. We will use the overall consensus of opinion to

help inform how we develop, and what we include, in

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

Page 3 of 7

our decision support package. It is not possible at the

time of writing to pre-judge the content and format of

the decision support package. As part of the design pro-

cess for the package we will invite comments from key

opinion leaders in back pain research nationally and

internationally to ensure that no key content has been

omitted.

Pilot RCT design

This study is a single centre randomised controlled trial

taking place in the physiotherapy service at NHS Coven-

try Community Physiotherapy. The physiotherapy ser-

vice sees around 300 patients as new back pain referrals

a month. The service uses a paper free referral system,

when patients are advised by their GP to attend the

physiotherapy service, it is the patients responsibility to

call the booking team and arrange an appointment.

Physiotherapists will be randomised to either receiving

training for the DSP or not. Subsequently patients will

be randomised to either a trained or a standard

physiotherapist.

Study population and eligibility criteria

One hundred and fifty participants seeking treatment

from the physiotherapy service at NHS Coventry Com-

munity Physiotherapy will be recruited. We will include

patients who have been advised by their GP to attend

physiotherapy. GPs are asked to refer those patients pre-

senting with LBP who do not return to normal activities

after 3-4 weeks. Earlier referrals can be made for

patients who are not coping with their pain e.g. the pain

has a significant effect upon daily living or they present

with poor prognosis which the GP is unable to address.

In all cases the GP would provide patients with the

Back Pain Access number. The patient is then free to

ring and directly book a 45 minute assessment appoint-

ment. GPs are asked to exclude patients if they have

signs of red flags, acute LBP of less than 3-4 weeks,

those already under secondary care, had recent lumbar

spine surgery, LBP as part of a presentation of multiple

body pains e.g. fibromyalgia, thoracic or cervical pain

and unstable psychiatric illness.

In this pilot RCT patients will be included if they are

seeking treatment for non specific LBP, they are aged

18 years and have fluent spoken and written English.

We will exclude patients with severe psychiatric or per-

sonality disorders, those with a terminal or critical ill-

ness and patients with possible serious spinal pathology

(e.g. tumour, infection or fracture).

Recruitment procedure

Following advice from their GP, the patient is given

information on how to get in touch with the booking

service to make an appointment (see figure 1). Those

who do so will be sent an invitation to join the study.

Interested participants will return the consent form and

completed baseline questionnaire to the research team.

Patients who meet the inclusion criteria, complete the

baseline questionnaire and consent to the trial will be

included. They will be randomised to either a DSP

trained physiotherapist or usual physiotherapy care. All

participants will attend a 45 minute one-to-one assess-

ment where they will be informed of the treatments on

offer and have the opportunity to discuss these.

Randomisation

We will randomise half of the 14 (five whole time equiva-

lents) physiotherapists to deliver the intervention. Patients

will then be randomised to physiotherapists. Once the

consent form and baseline questionnaire are received, the

physiotherapy department will call the Warwick Clinical

Trials Unit randomisation service to randomise the patient

to either the control or intervention arm. Clinic lists will

be adjusted to ensure participants have appointments with

the allocated therapists: control or intervention.

Outcome assessment

Our package of outcome measures is based on those we

have used successfully in two previous large scale com-

munity based trials of LBP treatments and are in line

with international recommendations [26,27].

a. Primary outcome measure

We will use satisfaction with treatment at three months

using a five-point Likert Scale (very satisfied to very dis-

satisfied) as our primary outcome. It is an amended ver-

sion of the standardised and recommended single-item

question [28]. Since a study of this size is unlikely to

show a change in clinical outcomes, satisfaction with

treatment is a useful outcome measure that is likely to be

more sensitive to change than clinical outcomes. If, in

this pilot, we can generate some evidence that we can

improve satisfaction, we will have justification for pro-

ceeding to a trial to test the impact on clinical outcomes.

b. Secondary outcome measures

Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)

[29] - The most commonly used measure of LBP-

related disability in primary care trials.

Modified Von Korff [30] - A measure of LBP &

disability over the preceding month.

SF-12 [31] - A generic measure of health-related

quality of life.

EuroQol [32] - A generic measure of health utility

that is designed for use in RCTs.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

[33] - An established and validated self rating instru-

ment for anxiety and depression.

Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) [34] - An

established measure self-efficacy for people with

chronic pain.

Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) [35]

- The physical sub-scale of FABQ measures attitude

to movement in back pain.

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

Page 4 of 7

Attendance - we will measure attendance from the

physiotherapy departments records.

Use of health services and costs

Immediate follow-up

The immediate follow-up assessment will focus on satis-

faction with the decision-making process. We will use

the Satisfaction with Decision Scale [36]. This is a tool

used to measure satisfaction with a health care decision.

The scale has been adapted and applied to other condi-

tions [37]. We will post this questionnaire to partici-

pants and ask them to return it by post to the study

team.

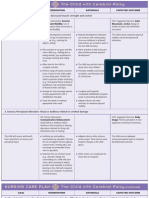

Figure 1 Pilot randomised controlled trial flow chart.

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

Page 5 of 7

Three-month follow-up

For this pilot RCT we will do a single follow-up after

three months, when treatment will be complete and

maximum benefit from treatment is expected. In addi-

tion to measuring satisfaction and repeating baseline

measures we will collect data on health service use and

health transition [38]. We will send follow-up question-

naires by post, three months after randomisation. We

will send postal reminders after two and four weeks,

and if necessary, we will collect a minimum data set by

phone from non-responders.

Sample size

In the Back Skills Training (BeST) trial, satisfaction with

treatment was measured using a five-point Likert Scale

(very satisfied to very dissatisfied) [23]. In this trial the

difference in satisfaction with treatment (a combination

of somewhat satisfied and very satisfied) at three

months was 23.6% compared to 54.3% for control and

treatment arm, respectively. Assuming satisfaction is

50% in the control group (similar to the treatment arm

in BeST), then to show a similar additional improve-

ment to 75% with 80% power at 5% significance level we

need data on 58 participants in each group. We have

not inflated the sample size to allow a design effect for

clustering by therapist. In our two previous trials of LBP

treatments, clustering effects by therapist were insignifi-

cant [26,27]. Thus, allowing for a 20% loss to follow up,

we need to recruit a minimum of 150 participants.

Data analysis

Descriptive summary statistics for demographic and

baseline data will be provided. The dichotomised

responses on the five point Likert scale to the treatment

satisfaction question will be analysed by means of a gen-

eralised linear mixed model with logit link, fixed effects

for intervention and baseline pain severity, and random

physiotherapist effects. The estimated intervention effect

(odds ratio) will be reported with 95% confidence inter-

val and p-value testing the null hypothesis of no inter-

vention effect. Continuous outcomes will be reported as

difference in change from baseline with its 95% confi-

dence interval.

Health economics

We will estimate the mean cost of the intervention and

other back pain-related NHS services and participants out

of pocket expenses over the three-month study period.

We will collect information on the cost of training for the

physiotherapists in the DSP group, including the cost of

the tutors time to prepare and deliver the training, the

cost of participants time, travel costs and materials.

Therapy cost will be collected from PCT records. The

three-month follow-up questionnaire will include ques-

tions about use of medication (prescribed and over-the-

counter), GP attendances, inpatient stays, outpatient

consultations, and visits to other therapists (NHS and

private). Healthcare cost will be estimated using unit costs

from the NHS tariff and standard references texts [39].

The within-trial difference in mean costs and the dif-

ference in mean quality adjusted life years (QALYs) will

be estimated with 95% confidence intervals, allowing for

the effects of treatment, baseline pain severity, and treat-

ing physiotherapist. These estimates will help us to

assess the potential benefits of conducting a definitive

trial and economic evaluation. For example, if the DSP

is associated with greater healthcare costs and no appar-

ent improvement in health outcomes over this initial

three-month period, it is unlikely that further research

would be worthwhile, particularly if there is also no

clear evidence of a strong patient preference for use of

the DSP. However, if cost savings and/or health

improvements are observed, it is possible that DSP may

be a cost-effective intervention and further research

would be warranted.

Acknowledgements

Funding: National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Research for Patient

Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Ref: PB-PG-0808-17039). This project benefited

from facilities funded through Birmingham Science City Translational Medicine

Clinical Research and infrastructure Trials platform, with support from

Advantage West Midlands.

Author details

1

University of Warwick, Clinical Trials Unit, Warwick Medical School, Gibbet

Hill Road, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK.

2

Universities/User Teaching and Research

Action Partnership (UNTRAP), Institute of Health School of Health and Social

Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK.

3

University Medical

Centre Gttingen, Department of Medical Statistics, Humboldtallee 32, D-

37073 Gttingen, Germany.

4

University of Warwick, Warwick Medical School,

Gibbet Hill Road, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK.

5

Brunel University, Health

Economics Research Group, Middlesex, UB8 3PH, UK.

6

University of Warwick,

Institute of Clinical Education, Warwick Medical School, Gibbet Hill Road,

Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK.

7

NHS Coventry Community Physiotherapy, Coventry

& Warwickshire Hospital, Stoney Stanton Road, CV1 4FH, UK.

Authors contributions

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

SB - has contributed to the design of the study and has commented on

draft versions of this manuscript. TF - has contributed to the design of the

study and is overseeing the quantitative analyses. TF has commented on

draft versions of this manuscript. FG - has contributed to the design of the

study and is overseeing the qualitative analyses. FG has commented on

draft versions of this manuscript. JL - has contributed to the design of the

study and is overseeing the economic analysis. AN - has commented on

draft versions of this manuscript. SP - has substantially contributed to the

conception and design of the study. SP has drafted this manuscript. CT - has

contributed to the design of the study and has commented on draft

versions of this manuscript. JT - has contributed to the design of the study

and is overseeing the intervention design. JT has commented on draft

versions of this manuscript. MW - has contributed to the design of the

study. MU - is the principal investigator. He has substantially contributed to

the conception and design of the study and obtaining the funding. MU has

critically commented on draft versions of the manuscript.

Competing interests

Martin Underwood was chair of the guideline development group for the

NICE Low back pain guidelines. Joanne Lord was employed by NICE at the

time of the development of the NICE Low Back Pain Guidelines and advised

the guideline development group on economic analysis. All other authors

declare that they have no competing interests.

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

Page 6 of 7

Received: 23 December 2010 Accepted: 25 February 2011

Published: 25 February 2011

References

1. Maniadakis N, Gray A: The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain

2000, 84(1):95-103.

2. Savigny P, Kuntze S, Watson P, Underwood M, Ritchie G, Cotterell M, Hill D,

Browne N, Buchanan E, Coffey P, Dixon P, Drummond C, Flanagan M,

Greenough C, Griffiths M, Halliday-Bell J, Hettinga D, Vogel S, Walsh D: Low

Back Pain: early management of persistent non-specific low back pain.

London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College

of General Practitioners; 2009 [http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/

CG88fullguideline.pdf].

3. Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J: Interventions for

providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical

consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, , Issue 4:

CD003267.

4. Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S: Shared decision-making interventions for

people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews 2010, , Issue 1: CD007297.

5. Stewart M: Patient-centred Medicine: transforming the clinical method Oxford:

Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003.

6. Thistlethwaite J, Heal C, Nan Tie R, Evans R: Shared decision-making and

decision aids - a literature review. Aust Fam Physician 2006, 35(7):537-40.

7. Edwards A, Elwyn G, Wood F, Atwell C, Prior L, Houston H: Shared

decision-making and risk communication in practice: a qualitative study

of GPs experiences. Br J Gen Pract 2005, 55(510):6-13.

8. Tomlinson T: The physicians influence on patients choices. Theorr Med

1968, 7:105-21.

9. Foster NE, Pincus T, Underwood MR, Vogel S, Breen AC, Harding G:

Treatment and the process of care in musculoskeletal conditions; a

multidisciplinary perspective and integration. Orthop Clin North Am 2003,

34:239-244.

10. OConnor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D,

Holmes-Rovner M, Tait V, Tetroe J, Fiset V, Barry M, Jones J: Decision aids

for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, , Issue 4: CD001431.

11. Myers SS, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Cherkin DC, Legedza A, Kaptchuk TJ,

Hrbek A, Buring JE, Post D, Connelly MT, Eisenberg DM: Patient

expectations as predictors of outcome in patients with acute low back

pain. J Gen Intern Med 2008, 23(2):148-53.

12. Preference Collaborative Review Group: Patients preferences within

randomised trials: systematic review and patient level meta-analysis. BMJ

2008, 31(337):a1864.

13. Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA: Lessons

from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient

expectations and treatment effects. Spine 2001, 26(13):1418-24.

14. Underwood MR, Morton V, Farrin A, UK BEAM Trial Team: Do baseline

characteristics predict response to treatment for low back pain?

Secondary analysis of the UK BEAM dataset. Rheumatology 2007,

46(8):1297-302.

15. Underwood M, Ashby D, Carnes D, Castelnuovo E, Cross P, Harding G,

Hennessy E, Letley L, Martin J, Mt-Isa S, Parsons S, Spencer A, Vickers M,

Whyte K: Topical or oral ibuprofen for chronic knee pain in older

people. The TOIB study. Health Technol Assess 2008, 12(22):ix-155.

16. Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM: Optimal matches of patient preferences for

information, decision-making and interpersonal behavior: evidence,

models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns 2006, 61(3):319-41.

17. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, Ferrier K,

Payne S: Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to

consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ 2001,

322(7284):468-72.

18. Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches C, Osborn R, Zapert K: Common

concerns amid diverse systems: health care experiences in five

countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003, 22(3):106-21.

19. Thistlethwaite J, Heal C, Nan Tie R, Evans R: Shared decision-making

between registrars and patientsweb based decision aids. Aust Fam

Physician 2007, 36(8):670-2.

20. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Hood K, Robling M, Atwell C, Russell I, Wensing M,

Grol R, Study Steering Group: Achieving involvement: process outcomes

from a cluster randomized trial of shared decision-making skill

development and use of risk communication aids in general practice.

Fam Pract 2004, 21(4):337-46.

21. OConnor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col NF, Eden KB, Entwistle VA,

Fiset V, Holmes-Rovner M, Khangura S, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D:

Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions.

Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2009, , Issue 8: CD001431.

22. Froud RJ: Improving interpretation of patient-reported outcomes in low

back pain trials. PhD thesis Queen Mary University of London; 2009.

23. Lamb SE, Lall R, Hansen Z, Castelnuovo E, Withers EJ, Nichols V, Griffiths F,

Potter R, Szczepura A, Underwood M, on behalf of the BeST trial group: A

multi-centred randomised controlled trial of a primary-care based

cognitive behavioural program for low back pain. The Back Skills

Training Trial - BeST. Health Technology Assessment Report .

24. Ritchie J, Spencer L: In Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research.

Edited by: Bryman A, Burgess RG. London: Routledge; 1994:173-94,

Analysing Qualitative Data.

25. Jones J, Hunter D: Using the Delphi and nominal group technique in

health services research. In Qualitative Research in Health Care. 2 edition.

Edited by: Pope C & Mays N. London: BMJ Books, BMJ Publishing Group;

1999:40-49.

26. Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, Castelnuovo E, Withers EJ, Nichols V, Potter R,

Underwood MR, on behalf of the Back Skills Training Trial investigators:

Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary

care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet

2010, 375(9718):916-923.

27. UK BEAM Trial TEAM (Underwood M): UK Back pain Exercise And

Manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical

treatments for back pain in primary care.. BMJ 2004, 229:1377-1381.

28. Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B,

Malmivaara A, Roland M, Von Korff M, Waddell G: Outcome measures for

back pain research: A proposal for standardised use. Spine 1998,

23(18):2003-13.

29. Roland M, Morris R: A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I:

development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-

back pain. Spine 1983, 8:141-144.

30. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF: Grading the severity of

chronic pain. Pain 1992, 50:133-149.

31. Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Abdalla MI, Buckingham JK, Russell IT: The SF36

health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for routine

use within the NHS? BMJ 1993, 306:1440-1444.

32. The EuroQol Group: EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of

health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16:199-208.

33. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983, 67:361-370.

34. Nicholas MK: Self-efficacy and chronic pain. Proceedings of the annual

conference of the British Psychological Society St. Andrews, Scotland; 1989.

35. Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ: A Fear-

Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance

beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993, 52:157-168.

36. Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, Rovner D, Lynn Breer M, Marilyn L,

Rothert ML, Padonu G, Talarczyk G: Patient Satisfaction with Health Care

Decisions: The Satisfaction with Decision Scale. Med Decis Making 1996,

16:58.

37. Wills CE, Holmes-Rovner M: Preliminary validation of the Satisfaction with

Decision scale with depressed primary care patients. Health Expect 2003,

6(2):149-59.

38. Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Koke AJ: Responsiveness of functional status in

low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain 1996,

65(1):71-6.

39. Curtis L, Netten A: Unit Costs of Health and Social Care Personal Social

Services Research Unit. Canterbury: University of Kent PSSRU; 2006.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52/prepub

doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-52

Cite this article as: Patel et al.: Study protocol: Improving patient choice

in treating low back pain (IMPACT - LBP): A randomised controlled trial

of a decision support package for use in physical therapy. BMC

Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011 12:52.

Patel et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12:52

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/52

Page 7 of 7

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- MDT World Press Newsletter Full PDF Vol2No3Document19 paginiMDT World Press Newsletter Full PDF Vol2No3Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact Factor 2016Document233 paginiImpact Factor 2016Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy Exam 1 Review - Muscles of the Back, Shoulder, Arm, Forearm & HandDocument27 paginiAnatomy Exam 1 Review - Muscles of the Back, Shoulder, Arm, Forearm & Handgdubs215Încă nu există evaluări

- Muscle Origin Insertion ActionsDocument14 paginiMuscle Origin Insertion ActionsAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Statistical Architecture For Economic Statistics: Ron Mckenzie Ices IiiDocument34 paginiA Statistical Architecture For Economic Statistics: Ron Mckenzie Ices IiiRishikesh KaushikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Uk and Countries March 2017 v1Document16 paginiChartered Society of Physiotherapy Uk and Countries March 2017 v1Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bio EnergeticsDocument23 paginiBio EnergeticsAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13 CIN Respiratory Assessment NotesDocument29 pagini13 CIN Respiratory Assessment NotesAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bers Resp No Anim 03Document65 paginiBers Resp No Anim 03Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavior and MedicineDocument32 paginiBehavior and MedicineAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Egeszsegugyi Ellatas Fuzet EngDocument16 paginiEgeszsegugyi Ellatas Fuzet EngAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phy Kompetenzprofil Englisch Fin 02106Document22 paginiPhy Kompetenzprofil Englisch Fin 02106Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patients' Rights in the European Union OverviewDocument30 paginiPatients' Rights in the European Union OverviewAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Services Co108 enDocument11 paginiHealth Services Co108 enAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- c1Document7 paginic1Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-2173 Physical Agent Catalog - 2Document16 pagini2012-2173 Physical Agent Catalog - 2Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Icahe Oc Incontinence User ManualDocument118 paginiIcahe Oc Incontinence User ManualAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainDocument5 pagini1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electrotherapy For Neck Pain (Review)Document106 paginiElectrotherapy For Neck Pain (Review)Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence Informed Practice Position Statement EnglishDocument2 paginiEvidence Informed Practice Position Statement EnglishAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Data Fisiotek HP2Document28 paginiClinical Data Fisiotek HP2Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colleague and Patient Questionnaires - PDF 44702599Document12 paginiColleague and Patient Questionnaires - PDF 44702599Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainDocument5 pagini1 s2.0 S0004951408700072 MainAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nu e Nimic InteresantDocument10 paginiNu e Nimic InteresantAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Physiotherapy Workforce Is Ageing, Becoming More Masculinised, and Is Working Longer Hours: A Demographic StudyDocument6 paginiThe Physiotherapy Workforce Is Ageing, Becoming More Masculinised, and Is Working Longer Hours: A Demographic StudyAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Should I: Warn The Patient First?Document7 paginiShould I: Warn The Patient First?Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Un Peu Du Ethics Pour RehabilitationDocument8 paginiUn Peu Du Ethics Pour RehabilitationAlexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 Leveraging Employee Engagement For Competitive Advantage 2Document12 pagini02 Leveraging Employee Engagement For Competitive Advantage 2faisalsiddique100% (2)

- J Hist Med Allied Sci 2005 Linker 320 54Document35 paginiJ Hist Med Allied Sci 2005 Linker 320 54Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scheda I-Tech Ue - Eng (Sp21-00)Document2 paginiScheda I-Tech Ue - Eng (Sp21-00)Alexandra NadinneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Priyanka ProjectDocument30 paginiPriyanka ProjectPriyanka ValluriÎncă nu există evaluări

- How manual therapy concepts have evolved from original researchDocument6 paginiHow manual therapy concepts have evolved from original researchismaelvara6568Încă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care For Patients With Musculoskeletal DisordersDocument4 paginiNursing Care For Patients With Musculoskeletal DisordersMark Russel Sean LealÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lec 12 - Drugs Used in PTDocument14 paginiLec 12 - Drugs Used in PTAiqa QaziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Association between acute low back pain and fear of movementDocument5 paginiAssociation between acute low back pain and fear of movementRadhamani ArunÎncă nu există evaluări

- TX Hospital Licensing Rules Table of ContentsDocument318 paginiTX Hospital Licensing Rules Table of ContentskazooedÎncă nu există evaluări

- WT-Natasha Dobby TEXTDocument4 paginiWT-Natasha Dobby TEXTjisha tom100% (3)

- NP 5Document6 paginiNP 5Ana Blesilda Cachola100% (1)

- Active Rehab for Back, Neck, Shoulder PainDocument57 paginiActive Rehab for Back, Neck, Shoulder PainLindawatiAjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bubble Wrap Gross Motor Skills ActivitiesDocument3 paginiBubble Wrap Gross Motor Skills ActivitiesNoreen GriffinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiotherapy Management of Acute Transverse Myelitis in A Pediatric Patient in A Nigerian Hospital: A Case ReportDocument9 paginiPhysiotherapy Management of Acute Transverse Myelitis in A Pediatric Patient in A Nigerian Hospital: A Case Reportluis bulnesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines For Data Collection On The American Nurses Association's National Quality Forum Endorsed MeasuresDocument21 paginiGuidelines For Data Collection On The American Nurses Association's National Quality Forum Endorsed MeasuresMaria Fudji HastutiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multiple Choice RatioDocument14 paginiMultiple Choice RatioDivine Joe Grace Marcelino100% (2)

- The Movement Continuum Theory of Physical Therapy-2Document2 paginiThe Movement Continuum Theory of Physical Therapy-2Ingela Sjölin100% (2)

- Certificate of DisabiltyDocument2 paginiCertificate of DisabiltyRizwan KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documentation For Physical Therapist Assistants by Wendy D. Bircher Wendy D. BircherDocument304 paginiDocumentation For Physical Therapist Assistants by Wendy D. Bircher Wendy D. BircherRickDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recommendations For Physiotherapy Intervention After Stroke 5712Document9 paginiRecommendations For Physiotherapy Intervention After Stroke 5712Anonymous Ezsgg0VSEÎncă nu există evaluări

- EXSA - Silver Award Recipients 2007Document8 paginiEXSA - Silver Award Recipients 2007applebarrelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Document PDFDocument12 paginiDocument PDFEviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business & Marketing PortfolioDocument28 paginiBusiness & Marketing PortfolioByng Sumague100% (3)

- Deborah Falla The Role of Motor Learning and Neuroplasticity in Designing RehabilitationDocument5 paginiDeborah Falla The Role of Motor Learning and Neuroplasticity in Designing RehabilitationDago Angel Prieto PalavecinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jessica Irwin Resume 2020 RNDocument2 paginiJessica Irwin Resume 2020 RNapi-300943374Încă nu există evaluări

- Process of Rehabilitation in PsychiatryDocument29 paginiProcess of Rehabilitation in PsychiatryRahul Kumar DiwakarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aquatic Therapy Journal Aug 2005 Vol 7Document28 paginiAquatic Therapy Journal Aug 2005 Vol 7Barbu Alexandru StefanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Superior Outcomes After Operative Fixation of Patella Fractures Using A Novel Plating Technique - A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument25 paginiSuperior Outcomes After Operative Fixation of Patella Fractures Using A Novel Plating Technique - A Prospective Cohort StudyAldrovando JrÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Another CountryDocument10 paginiIn Another CountryHồng NhungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan Goals for Child with Cerebral PalsyDocument3 paginiNursing Care Plan Goals for Child with Cerebral PalsyJamie Icabandi67% (3)

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 paginiCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelAdelina AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Rehabilitation Exercises Improve Joints MusclesDocument5 paginiMedical Rehabilitation Exercises Improve Joints MusclessylviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doors Pages From VA ARCH DESIGN MANUALDocument13 paginiDoors Pages From VA ARCH DESIGN MANUALMic BÎncă nu există evaluări