Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

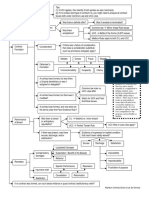

Crim Pro, Rules

Încărcat de

superxl20090 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

18 vizualizări2 paginiOutline

Titlu original

CrimPro,Rules[1]

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOC, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentOutline

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOC, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

18 vizualizări2 paginiCrim Pro, Rules

Încărcat de

superxl2009Outline

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOC, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 2

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution provides individual protection

from unreasonable searches and seizures. Article I 8 of the Pennslvania Constitution

e!tends this protection to its citizens and reco"nizes an even "reater protection of privac.

An unla#ful search of a person or place occurs #hen an individual has a sub$ective

e!pectation of privac in somethin" #hich societ reco"nizes as reasonable% and the

"overnment has violated this e!pectation of privac #ith a search.

Article I 8 of the Pennslvania Constitution presumes that to be reasonable% actions of

the "overnment amountin" to a search must be authorized b a valid search #arrant% and

searches not supported b such a #arrant are per se unreasonable.

A seizure of a person happens if in vie# of all the relevant circumstances% an ob$ectivel

reasonable person in the vie# of the defendant #ould not feel that the #ere free to

leave.

In Pennslvania% a chase&pursuit of a suspect is considered to be a seizure for #hich there

must be reasonable suspicion to support. An officer's approach carries #ith it indicia of

some form of intended detention or restriction on the individual's freedom( therefore% PA

la# re)uires reasonable suspicion or probable cause to be present( other#ise% an

relin)uishment that results #ill not be considered abandonment.

*elin)uishment durin" a mere encounter is deemed an abandonment.

In order to be valid a search #arrant must be sufficientl particular as to the person or

place to be searches and the person or thin" to be seized. The overall )uestion is #hether

the description in the #arrant is sufficient to limit the discretion of the e!ecutin" officials

and prevent a search of an area defined b the officer's inclination alone. If an

unreasonable discrepanc e!ists bet#een the items for #hich probable cause is

established and the description in the search #arrant% then suppression of the seized

evidence is re)uired.

Part of the Fourth Amendment's and Article I 8's re)uirement of reasonableness

includes that officers must use reasonable means to e!ecute a search #arrant.

Pennslvania has codified this in Pennslvania *ule of Criminal Procedure +,-. *ule

+,-% also .no#n as the /0noc. and Announce *ule%1 re)uires an officer to "ive% or ma.e

a reasonable effort to "ive% notice of the officer's identit% authorit% and reason of the

officer's entr to the e!ecute the #arrant to the occupant. The rule further re)uires the

officer to #ait a reasonable amount of time for a response b the occupant% absent e!i"ent

circumstances% before entr into the home. This rule e!ists because reasonableness

re)uires that an individual have an opportunit to peacefull surrender.

2

If the court finds that the defendant #as sub$ected to a custodial interro"ation% the

Common#ealth must prove that the person #as advised of his ri"ht to be free from self

incrimination as described in Miranda v. Arizona. Custod is found more readil in

Pennslvania than in federal courts and #ill be found #hen3 425 la# enforcement officials

phsicall deprived a person of his freedom of action( 4+5 the person had a reasonable

belief that his freedom of movement and action #as restricted b interro"ation( 465 the

person #as sub$ect to police detention that% because of the totalit of the circumstances%

became so coercive as to become the functional e)uivalent of an arrest( or 475 because of

an officer's sho# of authorit% the person #as led to believe that he #as not free to

decline the officer's re)uest or other#ise terminate the encounter.

In addition to direct )uestionin"% and conduct li.el to elicit an incriminatin" response

amounts to an interro"ation. Rhode Island v. Innis.

8nce a defendant is in custod% he must ma.e a .no#in"% intelli"ent% and voluntar

#aiver of his Miranda ri"hts in order to ma.e a statement. Moran v. Burbine; Comm v.

DeJesus. The Prosecution has the burden of provin" that a defendant .no#in"l%

voluntaril% and intelli"entl #aived his privile"e a"ainst self9incrimination. To do this

the must prove that the :'s #aiver #as the product of free and deliberate choice rather

than intimidation% coercion% or deception.

Those sub$ected to coercive police interro"ations have an automatic protection from the

use of their involuntar statements% or evidence derived from their statements% in an

subse)uent trial. US v. Patane; Adopted in PA b Comm v. Abbas.

;o#ever% if a statement is ta.en in violation of a :'s Miranda ri"hts% that statement is

sub$ect to suppression ho#ever it can be sued to support a subse)uent search #arrant and

evidence seized as a result of that #arrant is admissible.

The Si!th Amendment of the United States Constitution "uarantees a defendant a ri"ht to

counsel. 8fficiall% the ri"ht to counsel be"ins #hen formal adversar proceedin"s have

commenced. ;o#ever% before formal proceedin"s% the ri"ht to an attorne is contained in

Miranda as a <

th

Amendment protection. Therefore% a defendant has the ri"ht to counsel

as soon as the are in custod% but the defendant must specificall invo.e this ri"ht to it to

ta.e effect prior to $udicial proceedin"s.

The Confrontation Clause of the Si!th Amendment of the United States Constitution is

violated #hen at a criminal trial the Common#ealth attempts to offer into evidence a

testimonial statement of a currentl unavailable declarant #ho is unavailable for cross9

e!amination at trial and #ho #as not previousl cross9e!amined b the defendant. A

statement is considered to be testimonial if it #as made to a "overnment official #ith the

reasonable e!pectation that it #ould later be used prosecutorall.

+

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- 2011 0112 11 13 54 Document1Document1 pagină2011 0112 11 13 54 Document1superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Post Nuptial and Prenuptual Agreement EnforceabilityDocument1 paginăPost Nuptial and Prenuptual Agreement Enforceabilitysuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- 2016 05 10 10 52 45 Document2Document1 pagină2016 05 10 10 52 45 Document2superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- The Complete Defense: of Risk, Risk RiskDocument1 paginăThe Complete Defense: of Risk, Risk Risksuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Regulatory State Sitaraman 2014Document59 paginiRegulatory State Sitaraman 2014superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Scrutiny Categorization ChartDocument1 paginăScrutiny Categorization Chartsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- ConLaw FlowChartDocument2 paginiConLaw FlowChartAisha Lesley81% (16)

- MBE Hand Score Request FormDocument1 paginăMBE Hand Score Request Formsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Professional Responsibility Checklist for AttorneysDocument1 paginăProfessional Responsibility Checklist for Attorneyssuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Bar Exam Homicide Classification GuideDocument1 paginăBar Exam Homicide Classification Guidesuperxl2009100% (1)

- BE Tracker Form With Sig LineDocument1 paginăBE Tracker Form With Sig Linesuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- TORTS Outline For FinalDocument24 paginiTORTS Outline For Finalsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Evidence FlowchartDocument2 paginiEvidence Flowchartsuperxl200989% (9)

- Kucc FlowchartDocument1 paginăKucc Flowchartsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Wills Essay Law To Be AppliedDocument1 paginăWills Essay Law To Be Appliedsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Rules To Be AppliedDocument1 paginăRules To Be Appliedsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- ExplanationDocument1 paginăExplanationsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Civil Procedure Checklist - Organize Issues According to Lawsuit TimelineDocument1 paginăCivil Procedure Checklist - Organize Issues According to Lawsuit Timelinesuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Contracts Where Courts Are Divided: ConsiderationDocument1 paginăContracts Where Courts Are Divided: Considerationsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- DOS SLTort ChartDocument1 paginăDOS SLTort Chartsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- MBE Study ScheduleDocument8 paginiMBE Study ScheduleEmussel2Încă nu există evaluări

- Property Rights Attack OutlineDocument6 paginiProperty Rights Attack Outlinesuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Pa Contracts BarDocument1 paginăPa Contracts Barsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Con Law1 Unknown5Document1 paginăCon Law1 Unknown5superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Contracts I Roadmap - Selmi - Fall 2003 - 001Document1 paginăContracts I Roadmap - Selmi - Fall 2003 - 001superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Contracts I Roadmap - Selmi - Fall 2003 - 001Document1 paginăContracts I Roadmap - Selmi - Fall 2003 - 001superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Busorg ChecklistDocument2 paginiBusorg Checklistsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Con Law1 Unknown5Document1 paginăCon Law1 Unknown5superxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Cases and Materials On Employment DiscriminationDocument1 paginăCases and Materials On Employment Discriminationsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Cohabitation and Family Law Issues in Marvin v. MarvinDocument1 paginăCohabitation and Family Law Issues in Marvin v. Marvinsuperxl2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- 039 NLR NLR V 65 E. P. Seneviratne Appellant and Thaha RespondentDocument2 pagini039 NLR NLR V 65 E. P. Seneviratne Appellant and Thaha RespondentDinesh Kumara0% (1)

- PNP Revised Policy on Dropped From RollsDocument29 paginiPNP Revised Policy on Dropped From RollsEla Mae100% (2)

- 24 - Heirs of Gamboa v. TevesDocument3 pagini24 - Heirs of Gamboa v. TevesPRECIOUS JOY PACIONELAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warren County Civil PetitionDocument6 paginiWarren County Civil PetitionLocal 5 News (WOI-TV)Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Moot Prop 2019 PDFDocument4 paginiFinal Moot Prop 2019 PDFVaibhav JalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023 Pre-Week Notes - Criminal LawDocument92 pagini2023 Pre-Week Notes - Criminal LawCarrotman IsintheHouseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Rules on Constitutionality of Embroidery and Apparel Control LawDocument5 paginiSupreme Court Rules on Constitutionality of Embroidery and Apparel Control LawCiara Tralala CalungsudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lao Vs Dee Full TextDocument4 paginiLao Vs Dee Full TextSalie VillafloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule72 Musa Vs AmorDocument3 paginiRule72 Musa Vs AmorGil Ray Vergara OntalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1. Law Enforcement Agencies ARRESTDocument5 paginiLesson 1. Law Enforcement Agencies ARRESTSairan Ace AndradaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Directors Cannot Be Prosecuted Without Arraigning The Company As AccusedDocument7 paginiDirectors Cannot Be Prosecuted Without Arraigning The Company As AccusedLive Law100% (1)

- Lea Reporting PDFDocument13 paginiLea Reporting PDFDes MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal ConspiracyDocument3 paginiCriminal ConspiracySANTOSH MANDALEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bazar v. RuizolDocument2 paginiBazar v. Ruizolmaite fernandez100% (2)

- Abbas v. COMELEC FactsDocument12 paginiAbbas v. COMELEC FactsPaula Bianca Cedillo CorsigaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cooperation Between Police and ProsecutionDocument6 paginiCooperation Between Police and ProsecutionAsif Masood Raja100% (1)

- Warrantless Housing Inspection Ruled UnconstitutionalDocument2 paginiWarrantless Housing Inspection Ruled UnconstitutionalMonique LhuillierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tolentino V Sec of Finance DigestsDocument5 paginiTolentino V Sec of Finance DigestsDeb Bie100% (8)

- First Financial Insurance Company v. Debcon, Inc., B & B Construction Company, Inc., Defendant/third Party v. Andrew Martin, Sr. and Andrew Martin, JR., Third Party, 82 F.3d 418, 1st Cir. (1996)Document3 paginiFirst Financial Insurance Company v. Debcon, Inc., B & B Construction Company, Inc., Defendant/third Party v. Andrew Martin, Sr. and Andrew Martin, JR., Third Party, 82 F.3d 418, 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Civil Law Act MalaysiaDocument70 paginiThe Civil Law Act MalaysiaAngeline Tay Lee Yin100% (1)

- MDE Letter To Cros-LexDocument3 paginiMDE Letter To Cros-LexLiz ShepardÎncă nu există evaluări

- People VSDocument2 paginiPeople VSZonix LomboyÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is An Affidavit?Document16 paginiWhat Is An Affidavit?CDT LIDEM JOSEPH LESTERÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACAS Disciplinary and Grievance GuideDocument7 paginiACAS Disciplinary and Grievance Guidehamba0007Încă nu există evaluări

- Anti Terrorism Act 1997Document35 paginiAnti Terrorism Act 1997Jawaad KazmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lasalle Bank V Patrick PuentesDocument10 paginiLasalle Bank V Patrick PuentesRicharnellia-RichieRichBattiest-CollinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agdao Residents Association Directors Transfer Land Titles VoidDocument14 paginiAgdao Residents Association Directors Transfer Land Titles VoidFred Joven GlobioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Troherro Ketih BatisteDocument20 paginiTroherro Ketih BatisteThe Town TalkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ferrer V UstDocument4 paginiFerrer V UstemslansanganÎncă nu există evaluări

- SC Collegium Resolution Dated 22nd February, 2018 Reg. Appointment of Additional Judges As Permanent Judges in Rajasthan High Court.Document2 paginiSC Collegium Resolution Dated 22nd February, 2018 Reg. Appointment of Additional Judges As Permanent Judges in Rajasthan High Court.Latest Laws TeamÎncă nu există evaluări