Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

114 Full

Încărcat de

Camy CameliaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

114 Full

Încărcat de

Camy CameliaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

http://jme.sagepub.

com/

Education

Journal of Management

http://jme.sagepub.com/content/38/1/114

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1052562913488110

May 2013

2014 38: 114 originally published online 20 Journal of Management Education

Janine L. Bowen

Emotion in Organizations: Resources for Business Educators

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

OBTS Teaching Society for Management Educators

can be found at: Journal of Management Education Additional services and information for

http://jme.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://jme.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://jme.sagepub.com/content/38/1/114.refs.html Citations:

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

What is This?

- May 20, 2013 OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Jan 6, 2014 Version of Record >>

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Journal of Management Education

2014, Vol. 38(1) 114 142

The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1052562913488110

jme.sagepub.com

Research Article

Emotion in

Organizations: Resources

for Business Educators

Janine L. Bowen

1

Abstract

The study of emotion in organizations has advanced considerably in recent

years. Several aspects of this research area make calls for its translation into

business curricula particularly compelling. First, potential benefits to students

are significant. Second, important contributions to this scholarship often

come from the classroom. Third, emotions are part of the learning process

and, when aroused, improve learning and retention. Finally, given that the

study of emotion in organizations has become central to our understanding

of behavior at work, it is simply time to integrate current scholarly research

into education and practice. For all these reasons, this article has two aims:

to introduce business educators to the domain of emotion in organizations

for classroom use and to provide teaching resources to those starting to

integrate emotion into existing courses. References are provided for further

reading where discussion is necessarily abbreviated. Encouragement for

greater participation in the scholarship of teaching and learning in this area

is also provided.

Keywords

emotion in organizations, management education, experiential exercise,

emotional intelligence, emotional literacy, emotional contagion, emotional

climate, assessment

1

Goucher College, Baltimore, MD, USA

Corresponding Author:

Janine L. Bowen, Business Management Department, Goucher College, 1021 Dulaney Valley

Road, Baltimore, MD 21204, USA.

Email: jbowen@goucher.edu

488110JME38110.1177/1052562913488110Journal of Management EducationBowen

research-article2013

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 115

Introduction

In recent years, the study of emotion in organizations moved beyond its

infancy stage into what might be called adolescence. Interest since the 1980s

continues to grow such that there are now special issues of journals, edited

books, and book series on the subject (Ashkanasy, Dasborough, & Ascough,

2009; Ashkanasy & Humphrey, 2011; Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003;

Barsade & Gibson, 2007; Brief & Weiss, 2002; Kautish, 2010). Fueling the

interest is a desire to provide managers with practical tools to work with emo-

tion rather than avoid or dismiss it (Ashkanasy, Hartel, & Zerbe, 2002). We

are getting closer, it appears, to fulfilling Stephen Finemans (1993) hope that

emotion become a normal feature of organizational studieswhere it rightly

belongs (p. 2).

Several aspects of this research area make calls for its translation into

business curricula particularly compelling. First, potential benefits to stu-

dents are significant. Content knowledge and skill acquisition in this area are

associated not only with workplace preparation in general, but more specifi-

cally with group performance, decision making, leadership development,

interpersonal relationships, and stress reduction. Second, important contribu-

tions to this scholarship often come from the classroom (e.g., Ashkanasy &

Dasborough, 2003; Clark, Callister, & Wallace, 2003; Esmond-Kiger, Tucker,

& Yost, 2006; Liu, Xu, & Weitz, 2011; Ozcelik & Paprika, 2010; Sheehan,

McDonald, & Spence, 2009; Walsh-Portillo, 2011) and more is needed.

Emotions pervade the classroom as they do the workplace. Business course

staples like team projects, workplace simulations, and classroom-as-organi-

zation pedagogies facilitate the mimicry, creating research laboratories

through which the field can advance. Third, emotions are part of the learning

process and, when aroused and brought to consciousness, may improve

knowledge retention and recall (R. B. Brown, 2000; Forgas, 1995; Raelin &

Raelin, 2011; Steidl, Mohi-uddin, & Anderson, 2006). Finally, given that the

study of emotion in organizations has moved beyond the infancy stage to

become central concepts in our understanding of behavior at work

(Ashkanasy et al., 2009, p. 162), it is time to perform one of our prime respon-

sibilities as business educators to integrate current scholarly research into

education and practice.

For all these reasons, this article has two aims: to introduce business edu-

cators to the domain of emotion in organizations for classroom use and to

provide teaching resources to those starting to integrate emotion into existing

courses. References are provided for further reading where discussion is nec-

essarily abbreviated. Encouragement for greater participation in the scholar-

ship of teaching and learning in this area is also provided.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

116 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

An Introduction to Emotion and Emotion Theories

Business educators will find many theories and definitions of emotion from

which to choose for classroom use. This is because the nature of emotion has

been a matter of scientific debate for many years, with no end in sight.

Though the issues in question are innumerable, the role of cognition serves as

one relevant demarcation for the business classroom.

Some theories assert that there are basic emotions that are reflex-like,

requiring no evaluation or judgment, and are linked through evolution to the

instinctive behaviors of animals. Basic emotion refers to the affective pro-

cesses generated by evolutionarily old brain systems upon the sensing of an

ecologically valid stimulus (Izard, 2007, p. 261). Examples include fear,

anger, disgust, happiness, sadness, and surprise (Ekman, 1992; Levenson,

2011; Plutchik, 1980). The evolutionary hypothesis began with the work of

Charles Darwin (1872/1998) who searched for similarities in the expressions

of humans and animals, as well as across human cultures. Paul Ekman (1972)

and Carroll Izard (1971) likewise studied facial expressions and brought the

notion of basic emotions into modern times. Other major proponents include

Silvin Tomkins (1984), Robert Plutchik (1980), and Jaak Panksepp (1992).

As an illustration, students might imagine scenarios that would evoke the

same emotion in an animal, an infant, and an adult (e.g., eating a tasty treat or

a monster bursting through the door). Examples of facial expressions associ-

ated with basic emotions are easily found on the Internet for more entertain-

ing discussion.

Other theorists assert that cognition is a necessary element of emotion.

Examples include Lazarus and Folkman (1984), Frijda (1994), Roseman

(1984), and Scherer (2005). It is a cognitive process, they assert, whereby

information is manipulated (even at the unconscious level) that generates an

emotion response rather than a direct and automatic response to stimuli. And

it is the way in which information is manipulated (i.e., how an individual

evaluates or appraises the stimulus) that determines the emotion. The details

of appraisal systems account for many differences between theorists. The

intuitive appeal of cognitive appraisal theories may be illustrated for students

by considering scenarios whereby the same event (e.g., being laid-off) may

result in very different emotions in different people (e.g., anger or relief), or

why the same emotion (e.g., sadness) can be brought on by very different

scenarios. Hellriegel and Slocum (2010) present a model to students of how

cognition and emotions affect behavior and its use in industry. The process

starts with a goal that an individual is trying to accomplish (e.g., reaching a

sales or weight-loss target). Individuals tend to imagine (or are even asked to

imagine) the rewards that will come from attaining that goal (e.g., a bonus or

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 117

more attractive clothing). These thoughts evoke anticipatory emotions that, if

intensive enough, will trigger goal-oriented behaviors. Depending on whether

the goal is achieved, outcome emotions will be either positive or negative.

Fortunately, the two camps need not be considered mutually exclusive.

Izard (2009), for example, distinguishes basic emotion episodes (which are

automatic and short-lived) from emotion schemas (which are emotions

interacting with cognitive processes to influence mind and behavior).

Appraisal processes provide the cognitive framework for the emotional com-

ponent of the emotion schemas. Furthermore, emotion schemas develop over

time, from infanthood, and can be altered by experience. The role of cogni-

tion is but one of many matters under debate by emotion researchers. Others

include the structure of emotion (whether emotions are discrete/categorical

or continuous/circumplex), the role of consciousness, and a wide range of

definitional and measurement issues. For the business educator, no single

theory (or even classification of theories) need be chosen above all others.

Each explains a different aspect of emotion and is applicable in processes

across the organization. Emotions potential multifacetedness suggests that

any one approach to understanding it will be just thatone approach

(Fineman, 2004, p. 721).

Terminology, therefore, should be kept in general but easily understood

terms for the business classroom. Those provided by Barsade and Gibson

(2007) are representative of current textbook and article findings. Emotions

are focused on a specific target or cause, are generally realized by the per-

ceiver of the emotion, are relatively intense, and are very short-lived. After

initial intensity, they can sometimes transform into a mood. Examples include

love, anger, hate, fear, jealousy, happiness, sadness, grief, rage, aggravation,

ecstasy, affection, joy, envy, and fright. Moods generally take the form of a

global positive or negative feeling, tend to be diffuse (not focused on a spe-

cific cause), and often are not realized by the perceiver of the mood. They are

of medium duration (from a few moments to as long as a few weeks or more).

Examples include feeling good, bad, negative, positive, cheerful, down,

pleasant, irritable, and so on. A dispositional (trait) affect is an overall person-

ality tendency to respond to situations in stable, predictable ways. It is a per-

sons affective lens on the world. For example, No matter what, hes always

in the same mood.

Content and Skill Areas

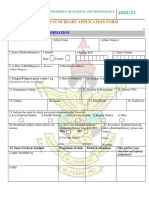

A conceptual model is useful to locate where and how emotions pervade the

workplace. Ashkanasy (2003) provides such a model of the five levels of

emotion in the workplace (see Figure 1).

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

118 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

Figure 1. Five levels of emotions in organizations.

Source: Ashkanasy (2003).

Level 1: Within-Person Phenomena

Emotions originate within individuals. As discussed above, there are emo-

tions that appear to be instinctive, automatic responses to stimuli in the envi-

ronment (noncognitive), whereas others seem to be the result of how we

interpret and make meaning of external stimuli (cognitive). Educators who

wish to introduce students to contributions from neuroscience on this matter

will find the work of Antonio Damasio (1994) of interest. His somatic marker

hypothesis explains the biology of emotion and its important role in decision

making. Theories used in organizational studies more frequently come from

psychology with a heavy focus on cognition. Affective events theory (AET)

is a fitting organizational theory for the within-person level of discussion.

Developed by Weiss and Cropanzano in 1996, AET centers on the causes and

consequences of individuals moods and emotions in the workplace, such as

the relationship between affect and job satisfaction. Events at work (so-called

uplifts and hassles) cause emotional reactions, which, depending on per-

sonality and mood, affect the intensity of short-term behavior and influence

overall feelings about the job as they aggregate in the longer-term (Brief &

Weiss, 2002; Grandey, Tam, & Brauburger, 2002). For business educators,

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 119

the theory offers useful framing of the relationships between work environ-

ment, work events, personal dispositions, emotional reactions, and various

outcomes, such as job satisfaction and job performance. Robbins and Judge

(2007) illustrate the theory for students by describing the emotional ups and

downs of anticipating layoffs and the effects on job performance and

satisfaction.

Level 2: Between-Person Differences

The Ashkanasy model graduates our focus from the emotional process within

an individual to the emotional differences between people. Differences in

trait affects, for example, might be illustrated by asking students if they know

anyone who always seems to wear rose colored glasses or perhaps is more

like Eeyore from Winnie-the-Pooh. A well-known model of positive and neg-

ative trait affect was developed by Watson and Tellegen (1985). They fall in

the continuous/circumplex camp of theorists who assert that each emotion is

a combination of two or three dimensions (in their case, positive and negative

affectivity). Because a person is believed to have some of both, the concep-

tual model has two axes, creating four quadrants. It is measured with the

Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale, a 20-item questionnaire developed

with a sample of undergraduates and validated with adult populations

(Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988).

For business educators, perhaps the most widely known theory used to

explain emotion differences between people is emotional intelligence (EI). EI

became popularized in the business world in the 1990s (Goleman, 1995;

Salovey & Mayer, 1990). As noted by Druskat and Wolff (2008), Controversy

over EI stems mostly from the abrupt speed with which it entered the litera-

ture, which was due to its almost instant popularity (p. 442). Researchers

debate and work to resolve definitional issues (e.g., whether EI is a set of

specific abilities or a broader mix of motivational and dispositional charac-

teristics), appropriate measurement instruments (which depend on the defini-

tion and whether subjects self-assess), and matters of mutability (i.e., the

extent to which EI can be taught). For classroom purposes, Ashkanasy et al.

(2009) argue that only the ability-based approach of Salovey and Mayer

should be taught, except for comparison purposes, because other approaches

lack a well-defined, organized construct. The associated abilities test is the

MSCEIT (Mayer, Salovey, Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; Mayer,

Salovey, & Caruso, 2002).

Empirical studies support a positive relationship between EI and various

outcomes, such as leadership effectiveness (Dasborough, Thomas, & Bowler,

2007; George, 2000; Kellett, Humphrey, & Sleeth, 2006; Kerr, Garvin,

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

120 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

Heaton, & Boyle, 2006; Palmer, Walls, Burgess, & Stough, 2000; Pescosolido,

2002; Pirola-Merlo, Hartel, Mann, & Hirst, 2002; Rosete & Ciarrochi, 2005;

Wolff, Pescosolido, & Druskat, 2002; Wong & Law, 2002), job satisfaction

and performance (Joseph & Newman, 2010; OBoyle, Humphrey, Pollack,

Hawver, & Story, 2011), team performance (Ashkanasy & Dasborough,

2003; Chang, Sy, & Choi, 2012), conflict resolution (Foo, Elfenbein, Tan, &

Aik, 2004; Jordan & Troth, 2004), and other workplace outcomes. As

described by Barsade and Gibson (2007), EI is a nascent field, theoretically

and methodologically. . . . We predict the construct of EI, particularly if

deconstructed into its component parts (e.g., the four factors), will ultimately

have much to offer our understanding of organizational life (pp. 40-41). The

four factors they refer to are from the Mayer and Salovey (1997) definition of

EI: (a) ability to perceive emotion, both in self and in others; (b) ability to

assimilate emotion into cognitive processes underlying thought; (c) ability to

understand emotion and its consequences; and (d) ability to manage and

thereby to regulate emotion in self and others. Cote and Hideg (2011) are

among those suggesting additional abilities contribute to EI. Their work

focuses on the differences in peoples ability to influence others through

emotion displays. Fortunately for business educators, published classroom

exercises and assignments designed to enhance EI, or emotion skills more

generally, are increasingly common, across a wide variety of business courses

and will be reviewed below.

Level 3: Interpersonal Exchanges

Following within-person processes and between-person differences,

Ashkanasys model moves next to emotional effects from dyadic exchanges.

People often try to increase, maintain, or decrease some part of their emo-

tional display in reaction to each other, which is called emotion regulation

(Gross, 1999). Examples include the salesperson who amplifies his display of

happiness to improve sales or the attorney who amplifies displeasure to affect

negotiations. When the act is done by an employee to comply with organiza-

tional demands (display rules), it is known as emotional labor (Hochschild,

1983). The difference between a felt emotion and the emotion an employee is

expected to display creates emotional dissonance. In response, the employee

may engage in surface acting (hiding inner feelings in response to display

rules) or deep acting (trying to modify inner feelings to be consistent with

display rules). Surface acting means altering how (or how much) an emotion

is displayed after it is fully felt and has been associated with psychological

ill-effects on the employee, such as emotional exhaustion, psychological

strain, and psychosomatic complaints (Beal, Trougakos, Weiss, & Green,

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 121

2006; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Brotheridge & Lee, 2002; Grandey,

2003; Grandey, Fisk, & Steiner, 2005; Holman, Chissick, & Totterdell, 2002;

Hulsheger & Schewe, 2011; Pugliesi, 1999). Deep acting, on the other hand,

requires altering how one appraises an event or stimuli to change the result-

ing emotion. Students may be reminded of cognitive appraisal theories of

emotion here. There are many fascinating studies of the consequences of sur-

face and deep acting, as well as the nature and sources of display rules (e.g.,

Bolton & Boyd, 2003; Callahan, 2002; Coupland, Brown, Daniels, &

Humphreys, 2008; Hulsheger & Schewe, 2011; Kramer & Hess, 2002; Miller,

Considine, & Garner, 2007; Rafaeli & Sutton, 2009; Tumbat, 2011). In-class

discussion of the findings can provide further nuance to the theory and are

highly relevant to students lives. The theory helps students recognize the

sources of display rules at work, the roles they themselves play as employees

and supervisors in the process, and possible consequences of prolonged emo-

tional dissonance for themselves and others.

Level 4: Group-Level Phenomenon

There is considerable research on emotion at the group level of analysis.

Most of it centers on the dynamics between leaders and followers and the

phenomenon of emotional contagion. Emotional contagion is the process by

which people influence the emotions of others by displaying their own emo-

tions and behaviors, consciously or unconsciously (Schoenewolf, 1990).

Beyond leadership courses, the topic is relevant in any business course that

uses team projects (which are typically designed to mimic workplace teams).

One place to start is the early work of Hatfield, Cacioppo, and Rapson (1992,

1994), who focused on interpersonal connections, such as the way people

mimic facial, vocal, and postural expressions; the varying abilities people

have to infect others; and their varying levels of susceptibility. Empirical

studies continue today from many disciplines such as animal research and

psychology. The study of leader and follower affect and emotions, more spe-

cifically, is relatively new. Key findings thus far are reported by Ashkanasy et

al. (2009), including that team emotion is promulgated through emotional

contagion (Barsade, 2002); team leaders communicate emotional states in

their followers (Sy, Cote, & Saavedra, 2005); leadermember exchange rela-

tionships have an impact on teammember exchange relationships (Seers,

1989), in a process involving group and team member affect (Tse &

Dasborough, 2008; Tse, Dasborough, & Ashkanasy, 2008); team members

emotional states affect their leaders affective states and effectiveness (Tee &

Ashkanasy, 2007); and teams develop the ability to recognize emotion as a

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

122 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

group (Elfenbein, Polzer, & Ambady, 2007), all of which provides rich and

highly relevant material for the business classroom.

Level 5: Organization-Wide Phenomenon

The organizational level of analysis is the least researched facet of emotions

in organizations to date, but arguably with the greatest potential (Ashkanasy

& Cooper, 2008, p. 11). For the business classroom, it is an opportunity for

students to learn about emotional climate in the workplace, which is distinct

from organizational culture. Emotional climate is the present social environ-

ment in the organization as perceived by the members of the organization

(Yurtsever & De Rivera, 2010, p. 502). Organizational culture, on the other

hand, is more stable over time as leaders and members come and go. Another

distinction is that climate can vary across sites of an organization whereas

culture does not (Ashkanasy & Nicholson, 2003). Emotional climate may be

less amenable to experiential exercises in the classroom, but a wide range of

reflective exercises that make use of students past experiences (see below)

can be very effective. Scholars are looking at ways to measure emotional

climate in organizations by separating it into eight emotional processes: secu-

rity, insecurity, confidence, depression, anger, love, fear, and trust (Yurtsever

& De Rivera, 2010). The descriptions and nuances of these eight processes

can facilitate productive discussion with students. Recent work by Sekerka

and Fredrickson (2008) and Hartel (2008) focus on how to build positive

emotional climates. For those interested in bringing the topic into the strate-

gic management classroom, Huy (2008) explains how emotions can enhance

strategic agility while Kumar (2008) describes the role of emotional dynam-

ics in strategic alliances.

Teaching Resources

To further aid business educators with integration of workplace emotion into

their courses, published classroom exercises and pedagogical approaches

were reviewed and are summarized below. Table 1 organizes them according

to the primary activity involved. Along the vertical axis are the levels of

Ashkanasys model to indicate how exercises might best be used to demon-

strate a particular content and skill area. Most exercises are highly adaptable,

however, to fit a given instructors objectives regarding emotion in

organizations.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 123

Mining Past Experience

As indicated in Table 1, using student reflection on past experience to illus-

trate emotion in organizations (at Levels 1 and 2) is a method provided by

Finan (2004), Litvin and Betters-Reed (2005), and McNeely (2000). They

point out that even undergraduates with limited work histories have consider-

able life experience from which to draw. Finan and McNeely draw out orga-

nizational experiences specifically through writing assignments, while Litvin

and Betters-Reed ask students to create a personal map based on significant

experiences that helped create their sense of self. Examples include collages,

model homes, and other three-dimensional constructs, poetry, and so on. The

authors detail each step of the assignments, when and how reference material

is introduced, steps for reflection and sharing in groups, debriefing tips, and

the like. Among their learning objectives are to surface students theories-in-

use, to give them confidence about what they already know, and to identify

questions that theory might answer. Evidence is provided to suggest that they

also increased reading of assigned material, increased interest in the course,

and improved learning retention. Not all were designed with emotion skills as

a specific learning outcome but all are perfectly suited to illustrate concepts

from AET and/or EI. R. B. Brown (2003) also draws on previous experience

in one of three exercises that are useful in conveying a sense of the basic

Table 1. Teaching Resources for Emotion in Organizations.

Teaching Resources for Emotion in Organizations

Model

Level

1

Within Person

2

Between

Person

3

Interpersonal

4

Group

5

Organizational

Brown

Myers &

Tucker

Boje

Reilly

Lewicki

et al.

Ozcelik &

Paprika

Pittenger &

Heimann

Sheehan et

al.

Miles et al.

Lindsay

Dugal &

Eriksen

Gibson

Brown

Finan

Litvin &

Beers-

Reed

McNeely

Brown

Past

Experience

Self

Assessment

Stories &

Cases

Drama Negotiations Classroom As

Organization

LTE

Myers &

Tucker

Brown

Ferris

Raelin &

Raelin

Huffaker &

West

Boggs et al.

Cross-cultural

exchanges

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

124 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

precepts of EI to students and in helping develop skills in emotionally intel-

ligent behavior (p. 122). With emphasis on interpersonal exchanges, it can

be used to illustrate Level 3 of Ashkanasys model. It involves journaling

about incidents that were emotionally charged to build awareness of how

often emotions are evoked and their effects on behavior. After stories are

shared in small groups, the instructor facilitates creation of a master list of

emotions and a guided discussion about EI concepts. Dugal and Eriksen

(2004) also draw on previous experience but use selected quotes from

assigned text as the starting point from which students produce personal

interpretations and personal experiences that embody the meaning of the

quote. The emotional content of the experience is also shared between stu-

dents. The exercise is highly structured and has been used in undergraduate,

MBA, and PhD courses, including leadership and organizational develop-

ment, leadership and team building, cross-cultural management, international

management, and strategy. (Because instructors select the text and quotes, the

exercise can be used for any level of the organizational model.) Gibsons

(2006) exercise, titled Emotional Episodes at Work, targets the highest

level of emotion in organizations. Student reflection on emotional episodes

from their work lives leads to discussion about how organizations generate

display rules and the implications for individual and organizational effective-

ness. The purpose of this exercise is to emphasize emotions as a central,

rather than hidden, part of work life (p. 477).

Self-Assessment

Myers and Tucker (2005) provide a series of in- and out-of-class assignments

to increase awareness of EI in a business communications course. The first

part of the series includes completing an EI assessment, reading a short book

on EI, creating an EI self-improvement plan, and journaling student progress

on the plan weekly. The assigned book, Emotional Intelligence at Work

(Weisinger, 1998), is based on Salovey and Meyers EI theory and includes a

45-item scale to test EI. They report that the scale has been shown to have

reliable scores in two research studies of college students (Tucker, Yost,

Kirch, Cutright, & Esmond-Kiger, 2002; Yost, Tucker, & Barone, 2001) (p.

47). Similarly, R. B. Brown (2003) uses self-assessment as a conclusion to a

series of exercises designed to teach EI. She asks students to write a short

self-appraisal based on Golemans (1995) four components of EI: How do

you appraise yourself in the areas of (a) self-discipline and delayed gratifica-

tion, (b) emotional awareness and self-control, (c) optimism, and (d) empa-

thy (p. 131). Students are further asked to reflect on which skill area needs

most improvement for future career success and ways by which the area can

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 125

be strengthened. Both exercises help students reflect on within-person pro-

cesses, as well as differences in EI, making it suitable for addressing Levels

1 and 2 of the Ashkanasy model.

Storytelling and Case Writing

The power of good storytelling, particularly by corporate leaders, has filled

business periodicals since at least the 1980s. How-to books for executive

officers, branding managers, corporate trainers, and others continue to flour-

ish (e.g., Denning, 2011; Fog, Budtz, Munch, & Blanchette, 2010; Gargiulo,

2006, Guber, 2011; Lipman, 2006; Maxwell & Dickman, 2007; Parkin, 2010;

Simmons, 2007; Simmons & Lipman, 2006). Management scholars explore

the role of storytelling across a variety of industries and organizational con-

texts (A. A. Brown, 2010; Escalfoni, Braganholo, & Borges, 2011; Sanne,

2008; Tobin & Snyman, 2008). For classroom use, experiential teaching

handbooks often include storytelling (e.g., Alterio & McDrury, 2003; Beard

& Wilson, 2006; Silberman, 2007), including one specifically for business

educators (Reynolds & Vince, 2007). In practice, however, storytelling is not

a common teaching technique in the business classroom (except to the extent

formal case studies are considered a form of storytelling).

But for teaching about emotion in organizations, storytelling offers many

advantages. Boje (1991) advocates storytelling to strengthen a subset of lead-

ership skills that include accurately interpreting what people are experiencing

and translating those experiences into powerful stories that can affect

others.

Students conduct interviews with outside business people and are given

considerable guidance on storytelling techniques to bring emotion to life.

Similarly, Morgan and Dennehy (2004) have pairs and trios of students tell a

story, listen carefully, and then retell others stories in hope of building skills

in telling, listening, being empathetic, and noticing cues in emotion and body

language. Storytelling exercises such as these are creative vehicles for teach-

ing emotion issues at Levels 2 (between-person differences), 3 (interpersonal

exchanges), and 4 (group phenomena) of Ashkanasys model. The act of

interviewing another about emotional experiences at the workplace, and

understanding what is heard well enough to craft a story, is practice in emo-

tion skill in and of itself, which can be explicitly linked to EI (Level 2) at the

instructors discretion. Interview or story topics (e.g., recalling experiences

with emotional dissonance) can also be tailored by the instructor to reinforce

learning of interpersonal phenomena (Level 3). When stories are shared with

other students (and listened to by groups of students), the phenomenon of

emotional contagion and leaderfollower dynamics become evident. Most

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

126 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

students will recognize that a story well told can emotionally affect a large

group and potentially move them to action.

There is a similar approach described by Myers and Tucker (2005), but

students create case studies based on outside business interviews rather than

tell the stories of their interviewees (making it fitting for Levels 2 and 3, but

not 4). Like the others, this exercise is highly structured and time-intensive,

but requires less class time. Components of the assignment include prepara-

tory readings, identifying a businessperson interviewee, developing inter-

view questions based on Weisingers (1998) assessment scale, evoking

examples of difficult conversations with leaders during the interview, analyz-

ing the interview data, and developing a case study. The case study incorpo-

rates assigned readings and the students recommendations for how

communication between the interviewee and his/her leader can be improved.

As noted by the authors, this type of primary research, analysis, and synthesis

enhances the business curriculum by building student knowledge of EI (p.

50), as well as other content areas associated with emotion in organizations

as determined by the instructor.

Drama

The arts increasingly inspire new forms of experiential learning in the busi-

ness classroom. Role-playing, for example, is most common among pub-

lished approaches to teaching emotion in organizations. Myers and Tucker

(2005) ask students to analyze a hypothetical workplace scenario, using EI

concepts, before practicing and eventually performing a role-play of the main

characters. Other students are used as coaches who may interject comments

or suggestions during the role-play. R. B. Browns (2003) approach adds an

element of surprise and spontaneity because students who will, in turn, play

one of the central characters are removed from the room before the role-

playing begins. The entire class participates, playing members of the organi-

zation in the scenario, and discuss in advance the tack they will take with the

character who has yet to enter. In that way, the student entering the scene

belatedly will experience spontaneous emotions during the role-play, react to

them, and demonstrate emotional consequences for other students to witness.

Those playing other central characters will also directly experience spontane-

ous emotion as behaviors may be directed to them specifically. Ferriss (2009)

approach is similar to Browns in that a small number of main characters

actually feel certain emotions during the role play; however, other students

serve as observers (rather than participants) and complete feedback sheets to

facilitate an analysis of what happened through concepts of EI. Ferriss

example is also unique because it can be used in traditional, blended learning,

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 127

or online courses, using a webcam and electronic blackboard system. A writ-

ten paper assignment follows the experience. Raelin and Raelin (2011) have

students construct their own dramatic scenes, based on a given emotion, and

later discuss whether the impact was beneficial.

Further on the continuum of arts-based learning is Huffaker and Wests

(2005) use of improvisational forms in a business class. They report on events

from one particular course, enrolled by undergraduate and MBA students,

and provide instructions for three easily implemented improv forms for oth-

ers to try. In their view, benefits to improv are unique because participates

must shut off their internal critics, become intensely focused and present,

and listen carefully (p. 854). Also, when students spontaneously move from

intuition to acting, without thinking, self-revelations can contribute to a skill

set different than the cognitive, judgment-driven discrimination typically

honed in the business classroom (p. 862). Source materials for the improvi-

sations are easily customized to fit any content area or organization level

where emotion in the workplace occurs. Finally, interactive drama is also

being used by business educators. Boggs, Mickel, and Bolton (2007) and

their colleagues have reportedly incorporated interactive drama in more than

500 classroom sessions for more than 17,000 students. It differs from role-

playing or improv by using trained actors, which allows students to view the

scene as though it were actually happening. The authors provide empirical

evidence to support the soundness of this technique for student learning,

Because the vivid scenes are so memorable, the students are able later to

connect them effectively to management theory or their own experiences in

reflective journals or other written assessments (p. 832). The authors pro-

vide sample scripts, including the following: Corporate Culture, Executive

Decision Making and Crisis Communication, Discrimination in the

Workplace, and Ethics in Negotiation, all of which are a good fit for incorpo-

rating emotion in organizations into the classroom.

All six of the drama-based exercises provide considerable latitude for

instructors to target emotion at any of the five organizational levels. When

crafting (or even just watching) a dramatic scene, for example, students may

be asked to focus on the causes and consequences of any one characters

moods and emotions in the workplace (reinforcing the concepts of AET at

Level 1). Acting out (or witnessing) differences in trait affects or components

of EI serves to illustrate emotional differences between people (Level 2).

Scripted or spontaneous emotional reactions between characters can easily be

emphasized to demonstrate the interpersonal level of emotion in organiza-

tions (Level 3), while the potential for one characters emotion displays to

affect the feelings and behaviors of a larger group illustrates emotional con-

tagion and other Level 4 phenomena. Finally, dramatic scenes of real or

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

128 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

hypothetical organizations with palpable emotional climates and display

rules can be used to teach emotion at the organization-wide level (Level 5).

Instructors who want to delve deeper into students skills at handling high-

stakes emotional dialogues at work may benefit from the latest edition of

Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High (Patterson,

Grenny, McMillan, & Switzler, 2012).

Negotiation

Negotiation simulations are a form of role-playing but are distinct because

students focus on achieving a particular outcome, which they interpret as

personal accomplishment. Reilly (2005) shares his use of a negotiation simu-

lation for teaching the theory and practice of EI to law students. He argues

that not only law schools but also all professional degree-granting programs

should make training in emotion a curriculum staple. He details one simu-

lated negotiation exercise, known as Charlene Walker. Key characters

include Ms. Walker, a low-income mother of three, her attorney, a social

worker, and an assistant city attorney. Raw emotions tend to come quickly

to the fore, which seem to almost take the student actors by surprise (p.

305). Before long, play-acting transforms into genuine emotional behaviors

and responses. The debriefing includes discussion of EI with the aim of tran-

sitioning students away from a win-at-all-costs approach (and the high

emotion it evokes) to a mindset that encourages creativity, open mindedness,

and joint problem solving. He hopes for students to see negotiation as a form

of conversation and, therefore, every conversation a potential negotiation.

Given how common formal and informal negotiations are within any organi-

zation, Reillys materials are easily modified to fit most any business course,

whether to teach EI, emotional contagion, or other phenomena found at the

second and third levels of Ashkanasys model. In fact, many published nego-

tiation simulations can be transplanted to other courses where the emotion of

organizations is under study (e.g., Lewicki, Barry, & Saunders, 2009).

Cross-Cultural Exchanges

Similar to Reillys concern that emotion education is missing from law

courses, Ozcelik and Paprika (2010) find it lacking from cross-cultural busi-

ness courses. Cross-cultural interactions are inherently emotional because of

heightened uncertainty. This is due, in part, to differing norms regarding

how, when, and where people should express their emotions (p. 673). As one

remedy, Ozcelik and Paprika devised a videoconferencing approach to

develop emotional awareness in cross-cultural communication. It is ideally

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 129

suited for teaching concepts from Levels 1 to 3 for the multinational organi-

zation, or the organization with cross-border business dealings. In short, busi-

ness students in Budapest and northern California conducted a simulated

negotiation (based on a real-life case study) via videoconferencing.

Participants and observers were surveyed immediately thereafter, and after a

few days, about the emotions evoked and their role in the outcome. A shared

viewing, analysis, and discussion of the videotape are also included, along

with follow-up writing assignments. Real-time webcam connections (e.g.,

Windows Live Messenger) make this approach accessible to many business

educators interested in helping students explore the role of emotion in orga-

nizations operating across borders.

A low-technology option for teaching emotional awareness in cross-cul-

tural settings (which can be done in as little as 50 minutes) is a game called

Barnga. The fairly simple card game simulates a form of culture shock as

players move between groups who appear to be playing the same game but

are actually playing under different rules. Emotions quickly run high and are

aggravated by the fact that players cannot speak. During the debriefing ses-

sion, students quite easily make the connection between their experiences

during the simulation and those of businesspeople operating cross-culturally.

They also learn a great deal about their own emotional responses in uncertain

circumstances and potential consequences from their behavior (making it fit-

ting for teaching Levels 1-3 of Ashkanasys model). The game can be used in

a variety of courses, including organizational behavior, diversity manage-

ment, cross-cultural communication, international business, and so on

(Pittenger & Heimann, 1998).

Classroom as Organization

The Classroom as Organization (CAO) approach is promoted by Sheehan et

al. (2009) to develop emotional competency among students in any business

course with project-based activities, such as organizing a conference, a major

celebration (e.g., Earth Day), or a community service event. They employ

CAO pedagogy in a sport event management course whereby students man-

age and market a basketball festival on campus. The first learning outcome is

for students to gain content knowledge about event management, such as

budgeting, operations, marketing, and so on. The other is for students to

develop emotional competencies necessary to manage themselves and others

in an organizational setting. Specifically, these include the following: (a) self-

awareness, knowing ones internal states, preferences, resources, and intu-

itions; (b) self-management, managing ones internal states, impulses, and

resources; (c) social awareness, awareness of others feelings, needs, and

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

130 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

concerns; and (d) relationship management, adeptness at inducing desirable

responses in others (Goleman, 2001). Detail is provided on how the course

operates as an organization, with students assigned to functional departments,

wherein they create organizational norms and policies and set their own

agendas and goals.

To summarize, designing a course that simulates a functioning organization

promotes the establishment of a learning environment where students are exposed

to a high volume of interactions from which they can learn and develop emotional

competency. In addition, the course is more likely to contribute to students

emotional competency if they assume ownership, are emotionally invested, and

are committed to a core purpose and a set of core values. (p. 84)

Writing assignments help connect experiences to selected theory and concepts,

while exit interviews further assess student learning for the instructor. To assess

the approach more formally, a quasi-experimental posttest-only design was

employed, using two comparable courses being offered at the same university.

Quantitative and qualitative results collectively highlight the greater impact of

the CAO approach compared to traditional lecture and discussion approaches

on students emotional competency development (p. 91).

Another option for business educators who are interested in the CAO

approach, but for whom a real-life project is not available or appropriate, is

The Organization Game (Miles, Randolph, & Kemery, 1993). Though it is

now out of print and its paper-and-pen technology may seem antiquated, used

copies of the manual are still available online, and the 6-week simulation

remains a remarkably powerful tool, providing a realistic setting for experi-

encing and understanding emotions in a complex organization. The instructor

manual provides guidance on handling inevitably emotional outcomes.

Online business simulations are increasingly common and may also be con-

sidered. Given that the CAO approach encompasses the entirety of an organi-

zation, it can be used to teach emotion at all levels of Ashkanasys model. The

caveat provided by Sheehan et al. (2009), however, is that the course must be

designed, implemented and consistently managed to reinforce desired learn-

ing outcomes beyond the development of cognitive skill sets (p. 94). That is,

the teaching of emotion in organizations requires intentionality and careful

planning.

Learning Through Emotion

Finally, Lindsay (1992) provides not so much a classroom method or tech-

nique as a general approach to teaching called learning through emotion

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 131

(LTE). LTE is based on the premise that the emotions experienced in class

(by the instructor and students) are similar to what would be felt in other

organizational settings and thus are valid data about organizational reality.

Course design is much like it would be for any course, with lectures, read-

ings, and standard exercises from assigned texts. But the schedule is kept

flexible so that when emotions are expressed (such as frustration over test

grades) they can become the basis of classroom discussion and analysis. In

addition to flexibility, course design includes experiential exercises to pro-

vide ample opportunity for trust building and emotion displays. Lindsay

argues that exercises meant to evoke particular emotions be avoided. Only

the naturally occurring, spontaneous emotions occurring in a particular

semester are addressed, making each course highly personalized. As an

example, Lindsay herself spontaneously presented herself to the class as a

case study subject who was struggling with motivational issues. Students

were invited to serve as consultants, and through their questions, explored a

range of personal issues and emotions surrounding her professional motiva-

tion (or lack thereof). Afterward, students wrote consultant reports using

theory to explain her motivational problems.

Lindsay asserts that LTE goes beyond teaching that emotions exist at work

and have an effect on performance because it focuses on current emotional

involvement in the class experience. Although she uses LTE in organizational

behavior courses, it may be considered for any course where emotion in orga-

nizations is among the learning objectives. Because any given course is likely

to evoke emotions within individuals, create exchanges of emotion between

individuals, and contain emotions passed from a leader/instructor to the

group, it is applicable to Levels 1 to 4 of Ashkanasys model. As mentioned

by R. B. Brown (2003), LTE is risky and requires high levels of trust, and

perhaps is best used after the topics of emotion at work and EI have been

introduced.

Discussion

The review of published classroom exercises and pedagogical approaches

was provided as a resource for business educators who are starting to inte-

grate emotion into existing courses. The examples need not be taken whole-

sale into a given class session but rather are highly malleable to suit the

instructors goals and learning objectives. Large schools, with business fac-

ulty dedicated to one or few areas of expertise, may be more likely to desig-

nate one or two courses (e.g., Organizational Behavior or Diversity in the

Workplace) to cover the material. Smaller schools, with a given faculty mem-

ber covering a much broader range of courses, may be more likely to

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

132 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

integrate the material in smaller doses across the business curriculum (not

unlike the introduction of international and environmental issues in years

past). In any case, Raelin and Raelin (2011) encourage business educators to

steer away from previous tendencies to teach students that emotion in organi-

zations should be marginalized, controlled, or even fabricated for personal

gain. Rather, they should encourage students to engage in direct emotional

expression, followed by a dialogue about the advantages and disadvantages

of emotional cognitization and control (p. 21).

The value and importance of that dialogue, or debriefing, make it worthy

of elaboration, particularly because emotions in the classroom can run high.

Instructors are encouraged to set and communicate clear goals for the debrief.

For example, does the instructor intend to debrief emotions only, which is not

about establishing facts of an incident but rather just expressing feelings? Or

is it also to reinforce learning of course material? Whatever the goals, ground

rules should be established (time permitting, with student input), such as no

interrupting, no name calling, attentive and respectful listening, and so on.

Instructors can facilitate the process with preplanned questions to prompt

discussion. Examples include the following: What emotions did you experi-

ence during the exercise? What new learning took place? What things you

already knew took on new meaning? Why do you think this exercise was

selected for this material? How does the exercise connect to real business

organizations? If conflict emerges during the debrief, instructors need to be

prepared to respond. That might include helping students distinguish between

dialogue and debate, reframing student comments so they are less personal,

taking a time-out to allow tempers to cool, and/or asking students to stop and

reflect their thoughts in writing before continuing with discussion. As the

discussion develops, instructors might write categories on the board (such as

personal reactions, events, problems, intended learning outcomes, etc.;

Burgess, 2007; Fritzsche, Leonard, Boscia, & Anderson, 2004).

When exercises and simulations go well, it can sometimes seem that a

debriefing is not necessary. But without the debrief, classroom exercises

become isolated experiences rather than opportunities for insight into real

organizational settings. And if things did not go smoothly and there were seri-

ous emotional reactions, learning may be compromised without effective

debriefing.

Educators using interactive exercises to teach emotion in organizations for

the first time should also give thought to how learning will be assessed. Informal

approaches may be appropriate in the early stages. Classroom Assessment

Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (Angelo & Cross, 1993) pro-

vides a comprehensive guide. CATs differ from formal approaches to assess-

ment because they are formative rather than evaluative or summative. That is,

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 133

their purpose is to improve the quality of student learning, not to provide evi-

dence for evaluating students. Angelo and Cross offer 50 distinct CATs from

which to choose, including 14 specifically for assessing learner attitudes, val-

ues, and self-awareness. The development of emotion skills goes beyond the

cognitive processes with which business educators are most familiar. Therefore,

new approaches to student learning assessment may also be needed.

Turning Teaching Into Scholarship

Emotion in organizations as a field of study has benefitted significantly from

the scholarship of teaching and learning. For example, some have addressed

the question of EI mutability. Ashkanasy and Dasborough (2003) used an

undergraduate leadership course to determine that interest in, and knowledge

of, EI predicted team performance. Similarly, Esmond-Kiger et al. (2006)

learned from their accounting students that prior exposure to the concept of

EI, in turn, affected EI levels. More recently, Sheehan et al. (2009) found that

the type of instruction (CAO vs. lecture) was associated with emotional com-

petency development. Others have used the classroom to explore the relation-

ship between EI and academic success (e.g., Barchard, 2003; Le, Casillas,

Robbins, & Langley, 2005; Liu et al., 2011; Walsh-Portillo, 2011).

Business faculty are uniquely positioned to contribute more to the research

domain of emotion in organizations because course staples like team proj-

ects, workplace simulations, CAO approaches, and the like mimic real orga-

nizational activities, turning classrooms into research laboratories. Applying

EI concepts to team performance (e.g., the role of individual EI vs. team EI

and performance outcomes) is one area for exploration. Replication of stud-

ies across schools would also be helpful. Theories beyond EI can also be

addressed. And given that an internship experience often accompanies busi-

ness program requirements, the effects of classroom teaching about emotion

can be followed through to real work performance. There is also the largely

untouched area of emotion and teaching in higher education. Do instructors

engage in emotional labor? If so, what are the effects? Do instructor emotion

skills lead to more effective teaching? What is the role of classroom emo-

tional contagion between instructor and students and how does it affect stu-

dent performance, or instructor performance?

As previously mentioned, business educators new to the domain may

begin with informal assessments to gauge and improve the effects of class-

room teaching on student learning. Scholarship of teaching and learning

about emotion in organizations is the next logical step as informal assess-

ments can graduate to become more formal measurements of student learning

and performance in business-like situations (e.g., team projects).

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

134 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

Conclusion

The notion that emotions permeate organizations, and affect individual,

group, and organizational performance, is not up for debate. The next ques-

tion is, Do we know enough about those effects to bring them into our cur-

ricula? The introductory domain review provided here allows business

educators to answer affirmatively. The study of emotion in organizations,

though fairly new, has advanced sufficiently for business educators to trans-

late its most important findings into the classroom.

Although knowledge about emotion in organizations is necessary, it is not

sufficient. Skill building is also needed. For that reason, a comprehensive

review of experiential teaching exercises was also provided. They address

emotion at all levels of the organization, in many cases have been tested for

teaching effectiveness, and provide variety in classroom activity. The chal-

lenge they present, however, is that they are often designed to evoke emotion.

Faculty members, like managers, have long viewed emotion as something to

marginalize. If we are to teach students (i.e., future managers) that emotion is

to be understood and addressed directly as an informative resource, then we

have to lead by example in our classrooms. Faculty themselves have not nec-

essarily been trained in emotion skills. They will, in some ways, be students

in their own classrooms. For this reason, it may be wise to begin with reflec-

tive exercises before tackling exercises that evoke high emotion in real time.

Preplanned debriefing sessions are also strongly encouraged.

It has been the aim of this article to arm business faculty with the knowl-

edge and tools needed to better prepare students for the emotional processes

embedded in every organization. In doing so, faculty will also be equipped to

contribute new knowledge to the domain through their own scholarship of

teaching and learning.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Goucher

College and the Atchinson Fund.

References

Alterio, R., & McDrury, J. (2003). Learning through storytelling in higher educa-

tion: Using reflection and experience to improve learning. Oxford, England:

Routledge.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 135

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook

for college teachers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ashkanasy, N. M. (2003). Emotion in organizations: A multilevel perspective. In F.

Dansrereau & F. J. Yammarino (Eds.), Research in multi-level issues: Multi-

level issues in organizational behavior and strategy (Vol. 2, pp. 9-54). Oxford,

England: Elsevier/JAI Press.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Cooper, C. L. (2008). Introduction. In N. M. Ashkanasy & C.

L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to emotion in organizations (pp. 1-15).

Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Dasborough, M. T. (2003). Emotional awareness and emotional

intelligence in leadership teaching. Journal of Education in Business, 79, 18-22.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Dasborough, M. Y., & Ascough, K. W. (2009). Developing lead-

ers: Teaching about emotional intelligence and training in emotional skills. In S.

J. Armstrong & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The Sage handbook of management learn-

ing, education and development (pp. 161-183). London, England: Sage.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Hartel, C. E. J, & Zerbe, W. J. (2002). What are the management

tools that come out of this? In N. M. Ashkanasy, W. J. Zerbe, & C. E. J. Hartel

(Eds.), Managing emotions in the workplace (pp. 285-296). New York, NY: M.E.

Sharpe.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Humphrey R. H. (2011). Current emotion research in organiza-

tional behavior. Emotion Review, 3, 214-224.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Nicholson, G. J. (2003). Climate of fear in organizational set-

tings: Construct definition, measurement, and a test of theory. Australian Journal

of Psychology, 55, 24-29.

Barchard, K. A. (2003). Does emotional intelligence assist in the prediction of aca-

demic success? Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 840-858.

Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on

group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644-675.

Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in

organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.),

Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 3-52). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Barsade, S. G., & Gibson, D. E. (2007). Why does affect matter in organizations?

Academy of Management Perspectives, 21, 36-59.

Beal, D. J., Trougakos, J. P., Weiss, H. M., & Green, S. G. (2006). Episodic processes

in emotional labor: Perceptions of affective delivery and regulation strategies.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1053-1063.

Beard, C., & Wilson, J. P. (2006). Experiential learning: A best practice handbook for

educators and trainers. London, England: Kogan Page.

Boggs, J. G., Mickel, A. E., & Bolton, B. C. (2007). Experiential learning through

interactive drama: An alternative to student role plays. Journal of Management

Education, 31, 832-858.

Boje, D. (1991). Learning storytelling: Storytelling to learn management skills.

Journal of Management Education, 15, 279-294.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

136 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

Bolton, S. C., & Boyd, C. (2003). Trolley dolly or skilled emotion manager? Moving

on from Hochschilds managed heart. Work, Employment and Society, 17, 289-

308.

Brief, A. P., & Weiss, H. M. (2002). Organizational behavior: Affect in the work-

place. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 279-307.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout:

Comparing two perspectives of people work. Journal of Vocational Behavior,

60, 17-39.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. T. (2002). Testing a conservation of resources model

of the dynamics of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,

7, 57-67.

Brown, A. S. (2010). Storytelling in risk management. Nurse Researcher, 17, 26-31.

Brown, R. B. (2000). Contemplating the emotional component of learning: The emo-

tions and feelings involved when undertaking an MBA. Management Learning,

31, 271-293.

Brown, R. B. (2003). Emotions and behavior: Exercises in emotional intelligence.

Journal of Management Education, 27, 122-134.

Burgess, H. (2007). Working with strong emotions in the classroom: A guide for

teachers and students. Retrieved from http://teachingresourceguide.wikispaces.

com/Dev_StrongEmotions

Callahan, J. L. (2002). Masking the need for cultural change: The effects of emotion

structuration. Organization Studies, 23, 281-297.

Chang, J. W., Sy, T., & Choi, J. N. (2012). Team emotional intelligence and per-

formance: Interactive dynamics between leaders and member. Small Group

Research, 43, 75-104.

Clark, S. C., Callister, R., & Wallace, R. (2003). Undergraduate management skills

courses and students emotional intelligence. Journal of Management Education,

27, 3-23.

Cote, S., & Hideg, I. (2011). The ability to influence others via emotional displays:

A new dimension of emotional intelligence. Organizational Psychology Review,

1, 53-71.

Coupland, C., Brown, A. D., Daniels, K., & Humphreys, M. (2008). Saying it with

feeling: Analyzing speakable emotions. Human Relations, 6, 327-353.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes error: Emotion, reason and the human brain. New

York, NY: G.P. Putnam.

Darwin, C. (1998). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. New York,

NY: Oxford University Press. (Original published 1862)

Dasborough, M. T., Thomas, J., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Utilizing your social net-

work and emotional skills to emerge as the team leader. Paper presented at the

Academy of Management Annual Meetings, Philadelphia, PA.

Denning, S. (2011). The leaders guide to storytelling: Mastering the art and disci-

pline of business narrative. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Druskat, V. U., & Wolff, S. B. (2008). Group-level emotional intelligence. In N. M.

Ashkanasy & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to emotion in organiza-

tions (pp. 441-454). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 137

Dugal, S. S., & Eriksen, M. (2004). Understanding and transcending team member

differences: A felt experience exercise. Journal of Management Education, 28,

492-508.

Ekman, P. (1972). Emotions in the human face. New York, NY: Pergamon Press.

Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions. Psychological Review, 99, 550-553.

Elfenbein, H. A., Polzer, J. T., & Ambady, N. (2007). Team Emotion recognition

accuracy and team performance. In C. E. J. Hartel, N. M. Ashkanasy, & W. J.

Zerbe (Eds.), Research on emotion in organizations (Vol. 3, pp. 89-119). Oxford,

England: Elsevier/JAI Press.

Escalfoni, R., Braganholo, V., & Borges, M. (2011). A method for capturing inno-

vation features using group storytelling. Expert Systems with Applications, 38,

1148-1159.

Esmond-Kiger, C., Tucker, M. L., & Yost, C. A. (2006). Emotional intelligence: From

the classroom to the workplace. Management Accounting Quarterly, 7, 35-42.

Ferris, W. (2009). Demonstrating the challenges of behaving with emotional intelli-

gence in a team setting: An on-line/on-ground experiential exercise. Organization

Management Journal, 6, 23-38.

Finan, M. C. (2004). Experience as teacher: Two techniques for incorporating student

experiences into a course. Journal of Management Education, 47, 478-491.

Fineman, S. (Ed.). (1993). Emotion in organizations. London, England: Sage.

Fineman, S. (2004). Getting the measure of emotionAnd the cautionary tale of

emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 57, 719-740.

Frijda, N. H. (1994). Emotions are functional, most of the time. In P. Ekman & R. J.

Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 112-122).

New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fog, K., Budtz, C., Munch, P., & Blanchette, S. (2010). Storytelling: Branding in

practice. New York, NY: Springer.

Foo, M. D., Elfenbein, H. A., Tan, H. H., & Aik, V. C. (2004). Emotional intelligence

and negotiation: The tension between creating and claiming value. International

Journal of Conflict Management, 15, 411-429.

Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect intrusion model (AIM).

Psychological Bulletin, 117, 39-66.

Fritzsche, D. J., Leonard, N. H., Boscia, M. W., & Anderson, P. H. (2004). Simulation

debriefing procedures. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential

Learning, 31, 337-338.

Gargiulo, T. L. (2006). Stories at work: Using stories to improve communication and

improve relationships. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

George, J. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence.

Human Relations, 53, 1027-1055.

Gibson, D. E. (2006). Emotional episodes at work: An experiential exercise in feeling

and expressing emotions. Journal of Management Education, 30, 477-500.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New

York, NY: Bantam.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

138 Journal of Management Education 38(1)

Goleman, D. (2001). An EI-based theory of performance. In C. Cherniss, D. Goleman,

& W. Bennis (Eds.), The emotionally intelligent workplace: How to select for,

measure, and improve emotional intelligence in individuals, groups, and organi-

zations (pp. 27-44). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When the show must go on: Surface acting and deep act-

ing as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery.

Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86-96.

Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., & Steiner, D. D. (2005). Must service with a smile

be stressful? The moderating role of personal control for American and French

employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 893-904.

Grandey, A. A., Tam, A. P., & Brauburger, A. L. (2002). Affective states and traits

in the workplace: Diary and survey data from young workers. Motivation and

Emotion, 26, 31-55.

Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion and emotion regulation. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John

(Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 525-552).

New York, NY: Guilford.

Guber, P. (2011). Tell to win: Connect, persuade and triumph with the hidden power

of story. New York, NY: Crown Business Books.

Hartel, C. E. J. (2008). How to build a healthy emotional culture and avoid a toxic cul-

ture. In N. M. Ashkanasy & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to emotion

in organizations (pp. 575-588). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. L. (1992). Primitive emotional contagion.

Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 14, 151-177.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional contagion. Cambridge,

England: Cambridge University Press.

Hellriegel, D., & Slocum, J. W. (2010). Organizational behavior. Mason, OH: South-

Western Cengage Learning.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Holman, D., Chissick, C., & Totterdell, P. (2002). The effects of performance moni-

toring on emotional labor and well-being in call centers. Motivation and Emotion,

26, 57-81.

Huffaker, J. S., & West, E. (2005). Enhancing learning in the business classroom: An

adventure with Improv Theater Techniques. Journal of Management Education,

29, 852-869.

Hulsheger, U. R., & Schewe, A. F. (2011). On the costs and benefits of emotional

labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Occupational

Health Psychology, 16, 361-389.

Huy, Q. N. (2008). How contrasting emotions can enhance strategic agility. In N. M.

Ashkanasy & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to emotion in organiza-

tions (pp. 546-560). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

Izard, C. E. (1971). The face of motion. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Izard, C. E. (2007). Basic emotions, natural kinds, emotion schemas, and a new para-

digm. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 260-280.

at National School of Political on September 2, 2014 jme.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Bowen 139

Izard, C. E. (2009). Emotion theory and research: Highlights, unanswered ques-

tions, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 1-25. doi:10.1146/

annurev.psych.60.110707.163539

Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2004). Managing emotions during team problem solv-

ing: Emotional intelligence and conflict resolution. Human Performance, 17,

195-218.

Joseph, D. L., & Newman, D. A. (2010). Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-

analysis and cascading model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 54-78.

Kautish, P. (2010). Emotional intelligence and business education: An analysis.

Journal of All India Association for Educational Research, 22, 89-100.

Kellett, J. B., Humphrey, R. H., & Sleeth, R. G. (2006). Empathy and the emergence

of task and relations leaders. Leadership Quarterly, 17, 162-164.

Kerr, R., Garvin, J., Heaton, N., & Boyle, E. (2006). Emotional intelligence and lead-

ership effectiveness. Leadership & Organizational Development Journal, 27,

265-279.

Kramer, M. W., & Hess, J. A. (2002). Communication rules for the display of emo-

tions in organizational settings. Management Communication Quarterly, 16, 66-

80.

Kumar, R. (2008). Contested meanings and emotional dynamics in strategic alliances.

In N. M. Ashkanasy & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to emotion in

organizations (pp. 561-574). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY:

Springer.

Le, H., Casillas, A., Robbins, S., & Langley, R. (2005). Motivational and skills, social

and self-management predictors of college outcomes: Constructing the student

readiness inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 482-508.

Levenson, R. W. (2011). Basic emotion questions. Emotion Review, 3, 379-386.

Lewicki, R. J., Barry, B., & Saunders, D. (2009). Negotiation: Readings, exercises

and cases. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Lindsay, C. (1992). Learning through emotion: An approach for integrating student

and teacher emotions into the classroom. Journal of Management Education, 16,

25-38.

Lipman, D. (2006). The storytelling coach: How to listen, praise, and bring out peo-

ples best. Atlanta, GA: August House.