Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hurl Assignement 4

Încărcat de

Winchelle Dawn Ramos LoyolaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hurl Assignement 4

Încărcat de

Winchelle Dawn Ramos LoyolaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

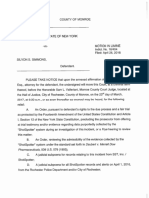

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. 7081 September 7, 1912

THE UNITED STATES, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

TAN TENG, defendant-appellant.

Chas A. McDonough, for appellant.

Office of the Solicitor General Harvey, for appellee.

JOHNSON, J .:

This defendant was charged with the crime of rape. The complaint alleged:

That on or about September 15, 1910, and before the filing of this complaint,

in the city of Manila, Philippine Islands, the said Tan Teng did willfully,

unlawfully and criminally, and employing force, lie and have carnal

intercourse with a certain Oliva Pacomio, a girl 7 years of age.

After hearing the evidence, the Honorable Charles S. Lobingier, judge, found the

defendant guilty of the offense ofabusos deshonestos, as defined and punished under

article 439 of the Penal Code, and sentenced him to be imprisoned for a period of 4

years 6 months and 11 days of prision correccional, and to pay the costs.

From that sentence the defendant appealed and made the following assignments of

error in this court:

I. The lower court erred in admitting the testimony of the physicians about

having taken a certain substance from the body of the accused while he was

confined in jail and regarding the chemical analysis made of the substance to

demonstrate the physical condition of the accused with reference to a

venereal disease.

II. The lower court erred in holding that the complainant was suffering from a

venereal disease produced by contact with a sick man.

III. The court erred in holding that the accused was suffering from a venereal

disease.

IV. The court erred in finding the accused guilty from the evidence.

From an examination of the record it appears that the offended party, Oliva Pacomio,

a girl seven years of age, was, on the 15th day of September , 1910, staying in the

house of her sister, located on Ilang-Ilang Street, in the city of Manila; that on said day

a number of Chinamen were gambling had been in the habit of visiting the house of

the sister of the offended party; that Oliva Pacomio, on the day in question, after

having taken a bath, returned to her room; that the defendant followed her into her

room and asked her for some face powder, which she gave him; that after using some

of the face powder upon his private parts he threw the said Oliva upon the floor,

placing his private parts upon hers, and remained in that position for some little time.

Several days later, perhaps a week or two, the sister of Oliva Pacomio discovered that

the latter was suffering from a venereal disease known as gonorrhea. It was at the

time of this discovery that Oliva related to her sister what happened upon the morning

of the 15th of September. The sister at once put on foot an investigation to find the

Chinaman. A number of Chinamen were collected together. Oliva was called upon to

identify the one who had abused her. The defendant was not present at first. later he

arrived and Oliva identified him at once as the one who had attempted to violate her.

Upon this information the defendant was arrested and taken to the police station and

stripped of his clothing and examined. The policeman who examined the defendant

swore from the venereal disease known as gonorrhea. The policeman took a portion

of the substance emitting from the body of the defendant and turned it over to the

Bureau of Science for the purpose of having a scientific analysis made of the same.

The result of the examination showed that the defendant was suffering from

gonorrhea.

During the trial the defendant objected strongly to the admissibility of the testimony of

Oliva, on the ground that because of her tender years her testimony should not be

given credit. The lower court, after carefully examining her with reference to her ability

to understand the nature of an oath, held that she had sufficient intelligence and

discernment to justify the court in accepting her testimony with full faith and credit.

With the conclusion of the lower court, after reading her declaration, we fully concur.

The defense in the lower court attempted to show that the venereal disease of

gonorrhea might be communicated in ways other than by contact such as is described

in the present case, and called medical witnesses for the purpose of supporting the

contention. Judge Lobingier, in discussing that question said:

We shall not pursue the refinement of speculation as to whether or not this

disease might, in exceptional cases, arise from other carnal contact. The

medical experts, as well as the books, agree that in ordinary cases it arises

from that cause, and if this was an exceptional one, we think it was

incumbent upon the defense to bring it within the exception.

The offended party testified that the defendant had rested his private parts upon hers

for some moments. The defendant was found to be suffering from gonorrhea. The

medical experts who testified agreed that this disease could have been communicated

from him to her by the contact described. Believing as we do the story told by Oliva,

we are forced to the conclusion that the disease with which Oliva was suffering was

the result of the illegal and brutal conduct of the defendant. Proof, however, that Oliva

constructed said obnoxious disease from the defendant is not necessary to show that

he is guilty of the crime. It is only corroborative of the truth of Oliva's declaration.

The defendant attempted to prove in the lower court that the prosecution was brought

for the purpose of compelling him to pay to the sister of Oliva a certain sum of money.

The defendant testifed and brought other Chinamen to support his declaration, that

the sister of Oliva threatened to have him prosecuted if he did not pay her the sum of

P60. It seems impossible to believe that the sister, after having become convinced

that Oliva had been outraged in the manner described above, would consider for a

moment a settlement for the paltry sum of P60. Honest women do not consent to the

violation of their bodies nor those of their near relatives, for the filthy consideration of

mere money.

In the court below the defendant contended that the result of the scientific examination

made by the Bureau of Science of the substance taken from his body, at or about the

time he was arrested, was not admissible in evidence as proof of the fact that he was

suffering from gonorrhea. That to admit such evidence was to compel the defendant to

testify against himself. Judge Lobingier, in discussing that question in his sentence,

said:

The accused was not compelled to make any admissions or answer any

questions, and the mere fact that an object found on his person was

examined: seems no more to infringe the rule invoked, than would the

introduction in evidence of stolen property taken from the person of a thief.

The substance was taken from the body of the defendant without his objection, the

examination was made by competent medical authority and the result showed that the

defendant was suffering from said disease. As was suggested by Judge Lobingier,

had the defendant been found with stolen property upon his person, there certainly

could have been no question had the stolen property been taken for the purpose of

using the same as evidence against him. So also if the clothing which he wore, by

reason of blood stains or otherwise, had furnished evidence of the commission of a

crime, there certainly could have been no objection to taking such for the purpose of

using the same as proof. No one would think of even suggesting that stolen property

and the clothing in the case indicated, taken from the defendant, could not be used

against him as evidence, without violating the rule that a person shall not be required

to give testimony against himself.

The question presented by the defendant below and repeated in his first assignment

of error is not a new question, either to the courts or authors. In the case of Holt vs.

U.S. (218 U.S., 245), Mr. Justice Holmes, speaking for the court upon this question,

said:

But the prohibition of compelling a man in a criminal court to be a witness

against himself, is a prohibition of the use of physical or moral compulsion, to

extort communications from him, not an exclusion of his body as evidence,

when it may be material. The objection, in principle, would forbid a jury

(court) to look at a person and compare his features with a photograph in

proof. Moreover we are not considering how far a court would go in

compelling a man to exhibit himself, for when he is exhibited, whether

voluntarily or by order, even if the order goes too far, the evidence if material,

is competent.

The question which we are discussing was also discussed by the supreme court of the

State of New Jersey, in the case of State vs. Miller (71 N.J. law Reports, 527). In that

case the court said, speaking through its chancellor:

It was not erroneous to permit the physician of the jail in which the accused

was confined, to testify to wounds observed by him on the back of the hands

of the accused, although he also testified that he had the accused removed

to a room in another part of the jail and divested of his clothing. The

observation made by the witness of the wounds on the hands and testified to

by him, was in no sense a compelling of the accused to be a witness against

himself. If the removal of the clothes had been forcible and the wounds had

been thus exposed, it seems that the evidence of their character and

appearance would not have been objectionable.

In that case also (State vs. Miller) the defendant was required to place his hand upon

the wall of the house where the crime was committed, for the purpose of ascertaining

whether or not his hand would have produced the bloody print. The court said, in

discussing that question:

It was not erroneous to permit evidence of the coincidence between the hand

of the accused and the bloody prints of a hand upon the wall of the house

where the crime was committed, the hand of the accused having been placed

thereon at the request of persons who were with him in the house.

It may be added that a section of the wall containing the blood prints was produced

before the jury and the testimony of such comparison was like that held to be proper in

another case decided by the supreme court of New Jersey in the case of Johnson vs.

State (30 Vroom, N.J. Law Reports, 271). The defendant caused the prints of the

shoes to be made in the sand before the jury, and the witnesses who had observed

shoe prints in the sand at the place of the commission of the crime were permitted to

compare them with what the had observed at that place.

In that case also the clothing of the defendant was used as evidence against him.

To admit the doctrine contended for by the appellant might exclude the testimony of a

physician or a medical expert who had been appointed to make observations of a

person who plead insanity as a defense, where such medical testimony was against

necessarily use the person of the defendant for the purpose of making such

examination. (People vs. Agustin, 199 N.Y., 446.) The doctrine contended for by the

appellants would also prevent the courts from making an examination of the body of

the defendant where serious personal injuries were alleged to have been received by

him. The right of the courts in such cases to require an exhibit of the injured parts of

the body has been established by a long line of decisions.

The prohibition contained in section 5 of the Philippine Bill that a person shall not be

compelled to be a witness against himself, is simply a prohibition against legal process

to extract from the defendant's own lips, against his will, an admission of his guilt.

Mr. Wigmore, in his valuable work on evidence, in discussing the question before us,

said:

If, in other words, it (the rule) created inviolability not only for his [physical

control] in whatever form exercised, then it would be possible for a guilty

person to shut himself up in his house, with all the tools and indicia of his

crime, and defy the authority of the law to employ in evidence anything that

might be obtained by forcibly overthrowing his possession and compelling the

surrender of the evidential articles a clear reductio ad absurdum. In other

words, it is not merely compulsion that is the kernel of the privilege, . . .

but testimonial compulsion. (4 Wigmore, sec. 2263.)

The main purpose of the provision of the Philippine Bill is to prohibit compulsory oral

examination of prisoners before trial. or upon trial, for the purpose of extorting

unwilling confessions or declarations implicating them in the commission of a crime.

(People vs. Gardner, 144 N. Y., 119.)

The doctrine contended for by appellant would prohibit courts from looking at the fact

of a defendant even, for the purpose of disclosing his identity. Such an application of

the prohibition under discussion certainly could not be permitted. Such an inspection

of the bodily features by the court or by witnesses, can not violate the privilege

granted under the Philippine Bill, because it does not call upon the accused as a

witness it does not call upon the defendant for his testimonial responsibility. Mr.

Wigmore says that evidence obtained in this way from the accused, is not testimony

but his body his body itself.

As was said by Judge Lobingier:

The accused was not compelled to make any admission or answer any

questions, and the mere fact that an object found upon his body was

examined seems no more to infringe the rule invoked than would the

introduction of stolen property taken from the person of a thief.

The doctrine contended for by the appellant would also prohibit the sanitary

department of the Government from examining the body of persons who are supposed

to have some contagious disease.

We believe that the evidence clearly shows that the defendant was suffering from the

venereal disease, as above stated, and that through his brutal conduct said disease

was communicated to Oliva Pacomio. In a case like the present it is always difficult to

secure positive and direct proof. Such crimes as the present are generally proved by

circumstantial evidence. In cases of rape the courts of law require corroborative proof,

for the reason that such crimes are generally committed in secret. In the present case,

taking into account the number and credibility of the witnesses, their interest and

attitude on the witness stand, their manner of testifying and the general circumstances

surrounding the witnesses, including the fact that both parties were found to be

suffering from a common disease, we are of the opinion that the defendant did, on or

about the 15th of September, 1910, have such relations as above described with the

said Oliva Pacomio, which under the provisions of article 439 of the Penal Code

makes him guilty of the crime of "abusos deshonestos," and taking into consideration

the fact that the crime which the defendant committed was done in the house where

Oliva Pacomio was living, we are of the opinion that the maximum penalty of the law

should be imposed. The maximum penalty provided for by law is six years of prision

correccional. Therefore let a judgment be entered modifying the sentence of the lower

court and sentencing the defendant to be imprisoned for a period of six years

of prision correccional, and to pay the costs. So ordered.

Arellano, C.J., Torres, Mapa, Carson and Trent, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-25018 May 26, 1969

ARSENIO PASCUAL, JR., petitioner-appellee,

vs.

BOARD OF MEDICAL EXAMINERS, respondent-appellant, SALVADOR

GATBONTON and ENRIQUETA GATBONTON, intervenors-appellants.

Conrado B. Enriquez for petitioner-appellee.

Office of the Solicitor General Arturo A. Alafriz, Assistant Solicitor General Antonio A.

Torres and Solicitor Pedro A. Ramirez for respondent-appellant.

Bausa, Ampil and Suarez for intervenors-appellants.

FERNANDO, J .:

The broad, all-embracing sweep of the self-incrimination clause,

1

whenever

appropriately invoked, has been accorded due recognition by this Court ever since the

adoption of the Constitution.

2

Bermudez v. Castillo,

3

decided in 1937, was quite

categorical. As we there stated: "This Court is of the opinion that in order that the

constitutional provision under consideration may prove to be a real protection and not

a dead letter, it must be given a liberal and broad interpretation favorable to the

person invoking it." As phrased by Justice Laurel in his concurring opinion: "The

provision, as doubtless it was designed, would be construed with the utmost liberality

in favor of the right of the individual intended to be served."

4

Even more relevant, considering the precise point at issue, is the recent case of Cabal

v. Kapunan,

5

where it was held that a respondent in an administrative proceeding

under the Anti-Graft Law

6

cannot be required to take the witness stand at the instance

of the complainant. So it must be in this case, where petitioner was sustained by the

lower court in his plea that he could not be compelled to be the first witness of the

complainants, he being the party proceeded against in an administrative charge for

malpractice. That was a correct decision; we affirm it on appeal.

Arsenio Pascual, Jr., petitioner-appellee, filed on February 1, 1965 with the Court of

First Instance of Manila an action for prohibition with prayer for preliminary injunction

against the Board of Medical Examiners, now respondent-appellant. It was alleged

therein that at the initial hearing of an administrative case

7

for alleged immorality,

counsel for complainants announced that he would present as his first witness herein

petitioner-appellee, who was the respondent in such malpractice charge. Thereupon,

petitioner-appellee, through counsel, made of record his objection, relying on the

constitutional right to be exempt from being a witness against himself. Respondent-

appellant, the Board of Examiners, took note of such a plea, at the same time stating

that at the next scheduled hearing, on February 12, 1965, petitioner-appellee would be

called upon to testify as such witness, unless in the meantime he could secure a

restraining order from a competent authority.

Petitioner-appellee then alleged that in thus ruling to compel him to take the witness

stand, the Board of Examiners was guilty, at the very least, of grave abuse of

discretion for failure to respect the constitutional right against self-incrimination, the

administrative proceeding against him, which could result in forfeiture or loss of a

privilege, being quasi-criminal in character. With his assertion that he was entitled to

the relief demanded consisting of perpetually restraining the respondent Board from

compelling him to testify as witness for his adversary and his readiness or his

willingness to put a bond, he prayed for a writ of preliminary injunction and after a

hearing or trial, for a writ of prohibition.

On February 9, 1965, the lower court ordered that a writ of preliminary injunction issue

against the respondent Board commanding it to refrain from hearing or further

proceeding with such an administrative case, to await the judicial disposition of the

matter upon petitioner-appellee posting a bond in the amount of P500.00.

The answer of respondent Board, while admitting the facts stressed that it could call

petitioner-appellee to the witness stand and interrogate him, the right against self-

incrimination being available only when a question calling for an incriminating answer

is asked of a witness. It further elaborated the matter in the affirmative defenses

interposed, stating that petitioner-appellee's remedy is to object once he is in the

witness stand, for respondent "a plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary

course of law," precluding the issuance of the relief sought. Respondent Board,

therefore, denied that it acted with grave abuse of discretion.

There was a motion for intervention by Salvador Gatbonton and Enriqueta Gatbonton,

the complainants in the administrative case for malpractice against petitioner-appellee,

asking that they be allowed to file an answer as intervenors. Such a motion was

granted and an answer in intervention was duly filed by them on March 23, 1965

sustaining the power of respondent Board, which for them is limited to compelling the

witness to take the stand, to be distinguished, in their opinion, from the power to

compel a witness to incriminate himself. They likewise alleged that the right against

self-incrimination cannot be availed of in an administrative hearing.

A decision was rendered by the lower court on August 2, 1965, finding the claim of

petitioner-appellee to be well-founded and prohibiting respondent Board "from

compelling the petitioner to act and testify as a witness for the complainant in said

investigation without his consent and against himself." Hence this appeal both by

respondent Board and intervenors, the Gatbontons. As noted at the outset, we find for

the petitioner-appellee.

1. We affirm the lower court decision on appeal as it does manifest fealty to the

principle announced by us in Cabal v. Kapunan.

8

In that proceeding for certiorari and

prohibition to annul an order of Judge Kapunan, it appeared that an administrative

charge for unexplained wealth having been filed against petitioner under the Anti-Graft

Act,

9

the complainant requested the investigating committee that petitioner be ordered

to take the witness stand, which request was granted. Upon petitioner's refusal to be

sworn as such witness, a charge for contempt was filed against him in the sala of

respondent Judge. He filed a motion to quash and upon its denial, he initiated this

proceeding. We found for the petitioner in accordance with the well-settled principle

that "the accused in a criminal case may refuse, not only to answer incriminatory

questions, but, also, to take the witness stand."

It was noted in the opinion penned by the present Chief Justice that while the matter

referred to an a administrative charge of unexplained wealth, with the Anti-Graft Act

authorizing the forfeiture of whatever property a public officer or employee may

acquire, manifestly out proportion to his salary and his other lawful income, there is

clearly the imposition of a penalty. The proceeding for forfeiture while administrative in

character thus possesses a criminal or penal aspect. The case before us is not

dissimilar; petitioner would be similarly disadvantaged. He could suffer not the

forfeiture of property but the revocation of his license as a medical practitioner, for

some an even greater deprivation.

To the argument that Cabal v. Kapunan could thus distinguished, it suffices to refer to

an American Supreme Court opinion highly persuasive in character.

10

In the language

of Justice Douglas: "We conclude ... that the Self-Incrimination Clause of the Fifth

Amendment has been absorbed in the Fourteenth, that it extends its protection to

lawyers as well as to other individuals, and that it should not be watered down by

imposing the dishonor of disbarment and the deprivation of a livelihood as a price for

asserting it." We reiterate that such a principle is equally applicable to a proceeding

that could possibly result in the loss of the privilege to practice the medical profession.

2. The appeal apparently proceeds on the mistaken assumption by respondent Board

and intervenors-appellants that the constitutional guarantee against self-incrimination

should be limited to allowing a witness to object to questions the answers to which

could lead to a penal liability being subsequently incurred. It is true that one aspect of

such a right, to follow the language of another American decision,

11

is the protection

against "any disclosures which the witness may reasonably apprehend could be used

in a criminal prosecution or which could lead to other evidence that might be so used."

If that were all there is then it becomes diluted.lawphi1.et

The constitutional guarantee protects as well the right to silence. As far back as 1905,

we had occasion to declare: "The accused has a perfect right to remain silent and his

silence cannot be used as a presumption of his guilt."

12

Only last year, in Chavez v.

Court of Appeals,

13

speaking through Justice Sanchez, we reaffirmed the doctrine

anew that it is the right of a defendant "to forego testimony, to remain silent, unless he

chooses to take the witness stand with undiluted, unfettered exercise of his own

free genuine will."

Why it should be thus is not difficult to discern. The constitutional guarantee, along

with other rights granted an accused, stands for a belief that while crime should not go

unpunished and that the truth must be revealed, such desirable objectives should not

be accomplished according to means or methods offensive to the high sense of

respect accorded the human personality. More and more in line with the democratic

creed, the deference accorded an individual even those suspected of the most

heinous crimes is given due weight. To quote from Chief Justice Warren, "the

constitutional foundation underlying the privilege is the respect a government ... must

accord to the dignity and integrity of its citizens."

14

It is likewise of interest to note that while earlier decisions stressed the principle of

humanity on which this right is predicated, precluding as it does all resort to force or

compulsion, whether physical or mental, current judicial opinion places equal

emphasis on its identification with the right to privacy. Thus according to Justice

Douglas: "The Fifth Amendment in its Self-Incrimination clause enables the citizen to

create a zone of privacy which government may not force to surrender to his

detriment."

15

So also with the observation of the late Judge Frank who spoke of "a

right to a private enclave where he may lead a private life. That right is the hallmark of

our democracy."

16

In the light of the above, it could thus clearly appear that no

possible objection could be legitimately raised against the correctness of the decision

now on appeal. We hold that in an administrative hearing against a medical

practitioner for alleged malpractice, respondent Board of Medical Examiners cannot,

consistently with the self-incrimination clause, compel the person proceeded against

to take the witness stand without his consent.

WHEREFORE, the decision of the lower court of August 2, 1965 is affirmed. Without

pronouncement as to costs.

Reyes, Dizon, Makalintal, Zaldivar, Sanchez and Capistrano, JJ., concur.

Teehankee and Barredo, JJ., took no part.

Concepcion, C.J., and Castro, J., are on leave.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. Nos. 71208-09 August 30, 1985

SATURNINA GALMAN AND REYNALDO GALMAN, petitioners,

vs.

THE HONORABLE PRESIDING JUSTICE MANUEL PAMARAN AND ASSOCIATE

JUSTICES AUGUSTO AMORES AND BIENVENIDO VERA CRUZ OF THE

SANDIGANBAYAN, THE HONORABLE BERNARDO FERNANDEZ,

TANODBAYAN, GENERAL FABIAN C. VER, MAJOR GENERAL PROSPERO

OLIVAS, SGT. PABLO MARTINEZ, SGT. TOMAS FERNANDEZ, SGT. LEONARDO

MOJICA SGT. PEPITO TORIO, SGT. PROSPERO BONA AND AlC ANICETO

ACUPIDO, respondents.

G.R. Nos. 71212-13 August 30, 1985

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, represented by the TANODBAYAN

(OMBUDSMAN), petitioner,

vs.

THE SANDIGANBAYAN, GENERAL FABIAN C. VER, MAJOR GEN. PROSPERO

OLIVAS, SGT. PABLO MARTINEZ, SGT. TOMAS FERNANDEZ, SGT. LEONARDO

MOJICA, SGT. PEPITO TORIO, SGT. PROSPERO BONA AND AIC ANICETO

ACUPIDO, respondents.

CUEVAS, JR., J .:

On August 21, 1983, a crime unparalleled in repercussions and ramifications was

committed inside the premises of the Manila International Airport (MIA) in Pasay City.

Former Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr., an opposition stalwart who was returning to

the country after a long-sojourn abroad, was gunned down to death. The

assassination rippled shock-waves throughout the entire country which reverberated

beyond the territorial confines of this Republic. The after-shocks stunned the nation

even more as this ramified to all aspects of Philippine political, economic and social

life.

To determine the facts and circumstances surrounding the killing and to allow a free,

unlimited and exhaustive investigation of all aspects of the tragedy,

1

P.D. 1886 was

promulgated creating an ad hoc Fact Finding Board which later became more

popularly known as the Agrava Board.

2

Pursuant to the powers vested in it by P.D.

1886, the Board conducted public hearings wherein various witnesses appeared and

testified and/or produced documentary and other evidence either in obedience to a

subpoena or in response to an invitation issued by the Board Among the witnesses

who appeared, testified and produced evidence before the Board were the herein

private respondents General Fabian C. Ver, Major General Prospero Olivas,

3

Sgt.

Pablo Martinez, Sgt. Tomas Fernandez, Sgt. Leonardo Mojica, Sgt. Pepito Torio, Sgt.

Prospero Bona and AIC Aniceto Acupido.

4

UPON termination of the investigation, two (2) reports were submitted to His

Excellency, President Ferdinand E. Marcos. One, by its Chairman, the Hon. Justice

Corazon Juliano Agrava; and another one, jointly authored by the other members of

the Board namely: Hon. Luciano Salazar, Hon. Amado Dizon, Hon. Dante Santos

and Hon. Ernesto Herrera. 'the reports were thereafter referred and turned over to the

TANODBAYAN for appropriate action. After conducting the necessary preliminary

investigation, the TANODBAYAN

5

filed with the SANDIGANBAYAN two (2)

Informations for MURDER-one for the killing of Sen. Benigno S. Aquino which was

docketed as Criminal Case No. 10010 and another, criminal Case No. 10011, for the

killing of Rolando Galman, who was found dead on the airport tarmac not far from the

prostrate body of Sen. Aquino on that same fateful day. In both criminal cases, private

respondents were charged as accessories, along with several principals, and one

accomplice.

Upon arraignment, all the accused, including the herein private ate Respondents

pleaded NOT GUILTY.

In the course of the joint trial of the two (2) aforementioned cases, the Prosecution

represented by the Office of the petition TANODBAYAN, marked and thereafter

offered as part of its evidence, the individual testimonies of private respondents before

the Agrava Board.

6

Private respondents, through their respective counsel objected to

the admission of said exhibits. Private respondent Gen. Ver filed a formal "Motion to

Exclude Testimonies of Gen. Fabian C. Ver before the Fact Finding Board as

Evidence against him in the above-entitled cases"

7

contending that its admission will

be in derogation of his constitutional right against self-incrimination and violative of the

immunity granted by P.D. 1886. He prayed that his aforesaid testimony be rejected as

evidence for the prosecution. Major Gen. Olivas and the rest of the other private

respondents likewise filed separate motions to exclude their respective individual

testimonies invoking the same ground.

8

Petitioner TANODBAYAN opposed said

motions contending that the immunity relied upon by the private respondents in

support of their motions to exclude their respective testimonies, was not available to

them because of their failure to invoke their right against self-incrimination before the

ad hoc Fact Finding Board.

9

Respondent SANDIGANBAYAN ordered the

TANODBAYAN and the private respondents to submit their respective memorandum

on the issue after which said motions will be considered submitted for resolution.

10

On May 30, 1985, petitioner having no further witnesses to present and having been

required to make its offer of evidence in writing, respondent SANDIGANBAYAN,

without the pending motions for exclusion being resolved, issued a Resolution

directing that by agreement of the parties, the pending motions for exclusion and the

opposition thereto, together with the memorandum in support thereof, as well as the

legal issues and arguments, raised therein are to be considered jointly in the Court's

Resolution on the prosecution's formal offer of exhibits and other documentary

evidences.

11

On June 3, 1985, the prosecution made a written "Formal Offer of

Evidence" which includes, among others, the testimonies of private respondents and

other evidences produced by them before the Board, all of which have been

previously marked in the course of the trial.

12

All the private respondents objected to the prosecution's formal offer of evidence on

the same ground relied upon by them in their respective motion for exclusion.

On June 13, 1985, respondent SANDIGANBAYAN issued a Resolution, now assailed

in these two (2) petitions, admitting all the evidences offered by the prosecution except

the testimonies and/or other evidence produced by the private respondents in view of

the immunity granted by P.D. 1886.

13

Petitioners' motion for the reconsideration of the said Resolution having been

DENIED, they now come before Us by way of certiorari

14

praying for the amendment

and/or setting aside of the challenged Resolution on the ground that it was issued

without jurisdiction and/or with grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of

jurisdiction. Private prosecutor below, as counsel for the mother of deceased Rolando

Galman, also filed a separate petition for certiorari

15

on the same ground. Having

arisen from the same factual beginnings and raising practically Identical issues, the

two (2) petitioners were consolidated and will therefore be jointly dealt with and

resolved in this Decision.

The crux of the instant controversy is the admissibility in evidence of the testimonies

given by the eight (8) private respondents who did not invoke their rights against self-

incrimination before the Agrava Board.

It is the submission of the prosecution, now represented by the petitioner

TANODBAYAN, that said testimonies are admissible against the private respondents,

respectively, because of the latter's failure to invoke before the Agrava Board the

immunity granted by P.D. 1886. Since private respondents did not invoke said

privilege, the immunity did not attach. Petitioners went further by contending that such

failure to claim said constitutional privilege amounts to a waiver thereof.

16

The private

respondents, on the other hand, claim that notwithstanding failure to set up the

privilege against self- incrimination before the Agrava Board, said evidences cannot

be used against them as mandated by Section 5 of the said P.D. 1886. They contend

that without the immunity provided for by the second clause of Section 5, P.D. 1886,

the legal compulsion imposed by the first clause of the same Section would suffer

from constitutional infirmity for being violative of the witness' right against self-

incrimination.

17

Thus, the protagonists are locked in horns on the effect and legal

significance of failure to set up the privilege against self-incrimination.

The question presented before Us is a novel one. Heretofore, this Court has not been

previously called upon to rule on issues involving immunity statutes. The relative

novelty of the question coupled with the extraordinary circumstance that had

precipitated the same did nothing to ease the burden of laying down the criteria upon

which this Court will henceforth build future jurisprudence on a heretofore unexplored

area of judicial inquiry. In carrying out this monumental task, however, We shall be

guided, as always, by the constitution and existing laws.

The Agrava Board,

18

came into existence in response to a popular public clamor that

an impartial and independent body, instead of any ordinary police agency, be charged

with the task of conducting the investigation. The then early distortions and

exaggerations, both in foreign and local media, relative to the probable motive behind

the assassination and the person or persons responsible for or involved in the

assassination hastened its creation and heavily contributed to its early formation.

19

Although referred to and designated as a mere Fact Finding Board, the Board is in

truth and in fact, and to all legal intents and purposes, an entity charged, not only with

the function of determining the facts and circumstances surrounding the killing, but

more importantly, the determination of the person or persons criminally responsible

therefor so that they may be brought before the bar of justice. For indeed, what good

will it be to the entire nation and the more than 50 million Filipinos to know the facts

and circumstances of the killing if the culprit or culprits will nevertheless not be dealt

with criminally? This purpose is implicit from Section 12 of the said Presidential

Decree, the pertinent portion of which provides

SECTION 12. The findings of the Board shall be made public.

Should the findings warrant the prosecution of any person, the

Board may initiate the filing of proper complaint with the appropriate

got government agency. ... (Emphasis supplied)

The investigation therefor is also geared, as any other similar investigation of its sort,

to the ascertainment and/or determination of the culprit or culprits, their consequent

prosecution and ultimately, their conviction. And as safeguard, the P.D. guarantees

"any person called to testify before the Board the right to counsel at any stage of the

proceedings."

20

Considering the foregoing environmental settings, it cannot be denied

that in the course of receiving evidence, persons summoned to testify will include not

merely plain witnesses but also those suspected as authors and co-participants in the

tragic killing. And when suspects are summoned and called to testify and/or produce

evidence, the situation is one where the person testifying or producing evidence is

undergoing investigation for the commission of an offense and not merely in order to

shed light on the facts and surrounding circumstances of the assassination, but more

importantly, to determine the character and extent of his participation therein.

Among this class of witnesses were the herein private respondents, suspects in the

said assassination, all of whom except Generals Ver and Olivas, were detained (under

technical arrest) at the time they were summoned and gave their testimonies before

the Agrava Board. This notwithstanding, Presidential Decree No. 1886 denied them

the right to remain silent. They were compelled to testify or be witnesses against

themselves. Section 5 of P.D. 1886 leave them no choice. They have to take the

witness stand, testify or produce evidence, under pain of contempt if they failed or

refused to do so.

21

The jeopardy of being placed behind prison bars even before

conviction dangled before their very eyes. Similarly, they cannot invoke the right not to

be a witness against themselves, both of which are sacrosantly enshrined and

protected by our fundamental law.

21

-a Both these constitutional rights (to remain

silent and not to be compelled to be a witness against himself) were right away totally

foreclosed by P.D. 1886. And yet when they so testified and produced evidence as

ordered, they were not immune from prosecution by reason of the testimony given by

them.

Of course, it may be argued is not the right to remain silent available only to a person

undergoing custodial interrogation? We find no categorical statement in the

constitutional provision on the matter which reads:

... Any person under investigation for the commission of an offense

shall have the right to remain and to counsel, and to be informed of

such right. ...

22

(Emphasis supplied)

Since the effectivity of the 1973 Constitution, we now have a mass of

jurisprudence

23

on this specific portion of the subject provision. In all these cases, it

has been categorically declared that a person detained for the commission of an

offense undergoing investigation has a right to be informed of his right to remain silent,

to counsel, and to an admonition that any and all statements to be given by him may

be used against him. Significantly however, there has been no pronouncement in any

of these cases nor in any other that a person similarly undergoing investigation for the

commission of an offense, if not detained, is not entitled to the constitutional

admonition mandated by said Section 20, Art. IV of the Bill of Rights.

The fact that the framers of our Constitution did not choose to use the term "custodial"

by having it inserted between the words "under" and investigation", as in fact the

sentence opens with the phrase "any person " goes to prove that they did not adopt in

toto the entire fabric of the Miranda doctrine.

24

Neither are we impressed by

petitioners' contention that the use of the word "confession" in the last sentence of

said Section 20, Article 4 connotes the Idea that it applies only to police investigation,

for although the word "confession" is used, the protection covers not only

"confessions" but also "admissions" made in violation of this section. They are

inadmissible against the source of the confession or admission and against third

person.

25

It is true a person in custody undergoing investigation labors under a more formidable

ordeal and graver trying conditions than one who is at liberty while being investigated.

But the common denominator in both which is sought to be avoided is the evil of

extorting from the very mouth of the person undergoing interrogation for the

commission of an offense, the very evidence with which to prosecute and thereafter

convict him. This is the lamentable situation we have at hand.

All the private respondents, except Generals Ver and Olivas, are members of the

military contingent that escorted Sen. Aquino while disembarking from the plane that

brought him home to Manila on that fateful day. Being at the scene of the crime as

such, they were among the first line of suspects in the subject assassination. General

Ver on the other hand, being the highest military authority of his co-petitioners labored

under the same suspicion and so with General Olivas, the first designated investigator

of the tragedy, but whom others suspected, felt and believed to have bungled the

case. The papers, especially the foreign media, and rumors from uglywagging

tongues, all point to them as having, in one way or another participated or have

something to do, in the alleged conspiracy that brought about the assassination. Could

there still be any doubt then that their being asked to testify, was to determine whether

they were really conspirators and if so, the extent of their participation in the said

conspiracy? It is too taxing upon one's credulity to believe that private respondents'

being called to the witness stand was merely to elicit from them facts and

circumstances surrounding the tragedy, which was already so abundantly supplied by

other ordinary witnesses who had testified earlier. In fact, the records show that

Generals Ver and Olivas were among the last witnesses called by the Agrava Board.

The subject matter dealt with and the line of questioning as shown by the transcript of

their testimonies before the Agrava Board, indubitably evinced purposes other than

merely eliciting and determining the so-called surrounding facts and circumstances of

the assassination. In the light of the examination reflected by the record, it is not far-

fetched to conclude that they were called to the stand to determine their probable

involvement in the crime being investigated. Yet they have not been informed or at the

very least even warned while so testifying, even at that particular stage of their

testimonies, of their right to remain silent and that any statement given by them may

be used against them. If the investigation was conducted, say by the PC, NBI or by

other police agency, all the herein private respondents could not have been compelled

to give any statement whether incriminatory or exculpatory. Not only that. They are

also entitled to be admonished of their constitutional right to remain silent, to counsel,

and be informed that any and all statements given by them may be used against them.

Did they lose their aforesaid constitutional rights simply because the investigation was

by the Agrava Board and not by any police investigator, officer or agency? True, they

continued testifying. May that be construed as a waiver of their rights to remain silent

and not to be compelled to be a witness against themselves? The answer is yes, if

they have the option to do so. But in the light of the first portion of Section 5 of P.D.

1886 and the awesome contempt power of the Board to punish any refusal to testify or

produce evidence, We are not persuaded that when they testified, they voluntarily

waived their constitutional rights not to be compelled to be a witness against

themselves much less their right to remain silent.

Compulsion as it is understood here does not necessarily connote

the use of violence; it may be the product of unintentional

statements. Pressure which operates to overbear his will, disable

him from making a free and rational choice, or impair his capacity

for rational judgment would in our opinion be sufficient. So is moral

coercion 'tending to force testimony from the unwilling lips of the

defendant.

26

Similarly, in the case of Louis J. Lefkowitz v. Russel

27

Turley" citing Garrity vs. New

Jersey" where certain police officers summoned to an inquiry being conducted by the

Attorney General involving the fixing of traffic tickets were asked questions following a

warning that if they did not answer they would be removed from office and that

anything they said might be used against them in any criminal proceeding, and the

questions were answered, the answers given cannot over their objection be later used

in their prosecutions for conspiracy. The United States Supreme Court went further in

holding that:

the protection of the individuals under the Fourteenth Amendment

against coerced statements prohibits use in subsequent

proceedings of statements obtained under threat or removal from

office, and that it extends to all, whether they are policemen or other

members of the body politic. 385 US at 500, 17 L Ed. 562. The

Court also held that in the context of threats of removal from office

the act of responding to interrogation was not voluntary and was not

an effective waiver of the privilege against self- incrimination.

To buttress their precarious stand and breathe life into a seemingly hopeless cause,

petitioners and amicus curiae (Ex-Senator Ambrosio Padilla) assert that the "right not

to be compelled to be a witness against himself" applies only in favor of an accused in

a criminal case. Hence, it may not be invoked by any of the herein private respondents

before the Agrava Board. The Cabal vs. Kapunan

28

doctrine militates very heavily

against this theory. Said case is not a criminal case as its title very clearly indicates. It

is not People vs. Cabal nor a prosecution for a criminal offense. And yet, when Cabal

refused to take the stand, to be sworn and to testify upon being called as a witness for

complainant Col. Maristela in a forfeiture of illegally acquired assets, this Court

sustained Cabal's plea that for him to be compelled to testify will be in violation of his

right against self- incrimination. We did not therein state that since he is not an

accused and the case is not a criminal case, Cabal cannot refuse to take the witness

stand and testify, and that he can invoke his right against self-incrimination only when

a question which tends to elicit an answer that will incriminate him is profounded to

him. Clearly then, it is not the character of the suit involved but the nature of the

proceedings that controls. The privilege has consistently been held to extend to all

proceedings sanctioned by law and to all cases in which punishment is sought to be

visited upon a witness, whether a party or not.

29

If in a mere forfeiture case where

only property rights were involved, "the right not to be compelled to be a witness

against himself" is secured in favor of the defendant, then with more reason it cannot

be denied to a person facing investigation before a Fact Finding Board where his life

and liberty, by reason of the statements to be given by him, hang on the balance.

Further enlightenment on the subject can be found in the historical background of this

constitutional provision against self- incrimination. The privilege against self-

incrimination is guaranteed in the Fifth Amendment to the Federal Constitution. In the

Philippines, the same principle obtains as a direct result of American influence. At first,

the provision in our organic laws were similar to the Constitution of the United States

and was as follows:

That no person shall be ... compelled in a criminal case to be a

witness against himself.

30

As now worded, Section 20 of Article IV reads:

No person shall be compelled to be a witness against himself.

The deletion of the phrase "in a criminal case" connotes no other import except to

make said provision also applicable to cases other than criminal. Decidedly then, the

right "not to be compelled to testify against himself" applies to the herein private

respondents notwithstanding that the proceedings before the Agrava Board is not, in

its strictest sense, a criminal case

No doubt, the private respondents were not merely denied the afore-discussed sacred

constitutional rights, but also the right to "due process" which is fundamental

fairness.

31

Quoting the highly-respected eminent constitutionalist that once graced

this Court, the former Chief Justice Enrique M. Fernando, due process

... is responsiveness to the supremacy of reason, obedience to the

dictates of justice. Negatively put, arbitrariness is ruled out and

unfairness avoided. To satisfy the due process requirement, official

action, to paraphrase Cardozo, must not outrun the bounds of

reason and result in sheer oppression. Due process is thus hostile

to any official action marred by lack of reasonableness. Correctly, it

has been Identified as freedom from arbitrariness. It is the

embodiment of the sporting Idea of fair play(Frankfurter, Mr. Justice

Holmes and the Supreme Court, 1983, pp. 32-33). It exacts fealty

"to those strivings for justice and judges the act of officialdom of

whatever branch "in the light of reason drawn from considerations of

fairness that reflect (democratic) traditions of legal and political

thought."(Frankfurter, Hannah v. Larche 1960, 363 US 20, at 487). It

is not a narrow or '"echnical conception with fixed content unrelated

to time, place and circumstances."(Cafeteria Workers v. McElroy

1961, 367 US 1230) Decisions based on such a clause requiring a

'close and perceptive inquiry into fundamental principles of our

society. (Bartkus vs. Illinois, 1959, 359 US 121). Questions of due

process are not to be treated narrowly or pedantically in slavery to

form or phrases. (Pearson v. McGraw, 1939, 308 US 313).

Our review of the pleadings and their annexes, together with the oral arguments,

manifestations and admissions of both counsel, failed to reveal adherence to and

compliance with due process. The manner in which the testimonies were taken from

private respondents fall short of the constitutional standards both under the DUE

PROCESS CLAUSE and under the EXCLUSIONARY RULE in Section 20, Article IV.

In the face of such grave constitutional infirmities, the individual testimonies of private

respondents cannot be admitted against them in ally criminal proceeding. This is true

regardless of absence of claim of constitutional privilege or of the presence of a grant

of immunity by law. Nevertheless, We shall rule on the effect of such absence of claim

to the availability to private respondents of the immunity provided for in Section 5, P.D.

1886 which issue was squarely raised and extensively discussed in the pleadings and

oral arguments of the parties.

Immunity statutes may be generally classified into two: one, which grants "use

immunity"; and the other, which grants what is known as "transactional immunity." The

distinction between the two is as follows: "Use immunity" prohibits use of witness'

compelled testimony and its fruits in any manner in connection with the criminal

prosecution of the witness. On the other hand, "transactional immunity" grants

immunity to the witness from prosecution for an offense to which his compelled

testimony relates."

32

Examining Presidential Decree 1886, more specifically Section 5

thereof, which reads:

SEC. 5. No person shall be excused from attending and testifying or

from producing books, records, correspondence, documents, or

other evidence in obedience to a subpoena issued by the Board on

the ground that his testimony or the evidence required of him may

tend to incriminate him or subject him to penalty or forfeiture; but his

testimony or any evidence produced by him shall not be used

against him in connection with any transaction, matter or thing

concerning which he is compelled, after having invoked his privilege

against self-incrimination, to testify or produce evidence, except that

such individual so testifying shall not be exempt from prosecution

and punishment for perjury committed in so testifying, nor shall he

be exempt from demotion or removal from office. (Emphasis

supplied)

it is beyond dispute that said law belongs to the first type of immunity statutes. It

grants merely immunity from use of any statement given before the Board, but not

immunity from prosecution by reason or on the basis thereof. Merely testifying and/or

producing evidence do not render the witness immuned from prosecution

notwithstanding his invocation of the right against self- incrimination. He is merely

saved from the use against him of such statement and nothing more. Stated otherwise

... he still runs the risk of being prosecuted even if he sets up his right against self-

incrimination. The dictates of fair play, which is the hallmark of due process, demands

that private respondents should have been informed of their rights to remain silent and

warned that any and all statements to be given by them may be used against them.

This, they were denied, under the pretense that they are not entitled to it and that the

Board has no obligation to so inform them.

It is for this reason that we cannot subscribe to the view adopted and urged upon Us

by the petitioners that the right against self-incrimination must be invoked before the

Board in order to prevent use of any given statement against the testifying witness in a

subsequent criminal prosecution. A literal interpretation fashioned upon Us is

repugnant to Article IV, Section 20 of the Constitution, which is the first test of

admissibility. It reads:

No person shall be compelled to be a witness against himself. Any

person under investigation for the commission of an offense shall

have the right to remain silent and to counsel, and to be informed of

such right. No force, violence, threat, intimidation, or any other

means which vitiates the free will shall be used against him. Any

confession obtained in violation of this section shall be inadmissible

in evidence. (Emphasis supplied)

The aforequoted provision renders inadmissible any confession obtained in violation

thereof. As herein earlier discussed, this exclusionary rule applies not only to

confessions but also to admissions,

33

whether made by a witness in any proceeding

or by an accused in a criminal proceeding or any person under investigation for the

commission of an offense. Any interpretation of a statute which will give it a meaning

in conflict with the Constitution must be avoided. So much so that if two or more

constructions or interpretations could possibly be resorted to, then that one which will

avoid unconstitutionality must be adopted even though it may be necessary for this

purpose to disregard the more usual and apparent import of the language used.

34

To

save the statute from a declaration of unconstitutionality it must be given a reasonable

construction that will bring it within the fundamental law.

35

Apparent conflict between

two clauses should be harmonized.

36

But a literal application of a requirement of a claim of the privilege against self-

incrimination as a condition sine qua non to the grant of immunity presupposes that

from a layman's point of view, he has the option to refuse to answer questions and

therefore, to make such claim. P.D. 1886, however, forecloses such option of refusal

by imposing sanctions upon its exercise, thus:

SEC. 4. The Board may hold any person in direct or indirect

contempt, and impose appropriate penalties therefor. A person

guilty of .... including ... refusal to be sworn or to answer as a

witness or to subscribe to an affidavit or deposition when lawfully

required to do so may be summarily adjudged in direct contempt by

the Board. ...

Such threat of punishment for making a claim of the privilege leaves the witness no

choice but to answer and thereby forfeit the immunity purportedly granted by Sec. 5.

The absurdity of such application is apparent Sec. 5 requires a claim which it,

however, forecloses under threat of contempt proceedings against anyone who makes

such claim. But the strong testimonial compulsion imposed by Section 5 of P.D. 1886

viewed in the light of the sanctions provided in Section 4,infringes upon the witness'

right against self-incrimination. As a rule, such infringement of the constitutional right

renders inoperative the testimonial compulsion, meaning, the witness cannot be

compelled to answer UNLESS a co-extensive protection in the form of IMMUNITY is

offered.

37

Hence, under the oppressive compulsion of P.D. 1886, immunity must in

fact be offered to the witness before he can be required to answer, so as to safeguard

his sacred constitutional right. But in this case, the compulsion has already produced

its desired results the private respondents had all testified without offer of immunity.

Their constitutional rights are therefore, in jeopardy. The only way to cure the law of its

unconstitutional effects is to construe it in the manner as if IMMUNITY had in fact

been offered. We hold, therefore, that in view of the potent sanctions imposed on the

refusal to testify or to answer questions under Sec. 4 of P.D. 1886, the testimonies

compelled thereby are deemed immunized under Section 5 of the same law. The

applicability of the immunity granted by P.D. 1886 cannot be made to depend on a

claim of the privilege against self-incrimination which the same law practically strips

away from the witness.

With the stand we take on the issue before Us, and considering the temper of the

times, we run the risk of being consigned to unpopularity. Conscious as we are of, but

undaunted by, the frightening consequences that hover before Us, we have strictly

adhered to the Constitution in upholding the rule of law finding solace in the view very

aptly articulated by that well-known civil libertarian and admired defender of human

rights of this Court, Mr. Justice Claudio Teehankee, in the case of People vs.

Manalang

38

and we quote:

I am completely conscious of the need for a balancing of the

interests of society with the rights and freedoms of the individuals. I

have advocated the balancing-of-interests rule in an situations

which call for an appraisal of the interplay of conflicting interests of

consequential dimensions. But I reject any proposition that would

blindly uphold the interests of society at the sacrifice of the dignity of

any human being. (Emphasis supplied)

Lest we be misunderstood, let it be known that we are not by this disposition passing

upon the guilt or innocence of the herein private respondents an issue which is before

the Sandiganbayan. We are merely resolving a question of law and the

pronouncement herein made applies to all similarly situated, irrespective of one's rank

and status in society.

IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATIONS and finding the instant petitions

without merit, same are DISMISSED. No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

Aquino, J., concurs (as certified by Makasiar, C.J.).

Abad Santos, J., is on leave.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-28025 December 16, 1970

DAVID ACEBEDO Y DALMAN, petitioner,

vs.

HON. MALCOLM G. SARMIENTO, as Judge of the Court of First Instance of

Pampanga and THE PROV. FISCAL OF PAMPANGA, respondents.

Filemon Cajator for petitioner.

Judge Malcolm G. Sarmiento in his own behalf.

Provincial Fiscal Regidor Y. Aglipay for and in his own behalf as respondent.

FERNANDO, J .:

This Court not so long ago reaffirmed the doctrine that where a dismissal of a criminal

prosecution amounts to an acquittal, even if arising from a motion presented by the

accused, the ban on being twice put in jeopardy may be invoked, especially where

such dismissal was predicated on the right to a speedy trial.

1

The specific question

then that this certiorari and prohibition proceeding presents is whether on the

undisputed facts, an order of dismissal given in open court by respondent Judge falls

within the operation of the above principle, precluding its reconsideration later as the

defense of double jeopardy would be available. Here respondent Judge did

reconsider, and his actuation is now assailed as a grave abuse of discretion. As will be

made apparent, petitioner has the law on his side. The writs should be granted.

It was shown that on August 3, 1959, respondent Provincial Fiscal filed in the Court of

First Instance of Pampanga a criminal information for damage to property through

reckless imprudence against petitioner and a certain Chi Chan Tan. As there were no

further proceedings in the meantime, petitioner on May 19, 1965 moved to dismiss the

criminal charge. Respondent Judge was not in agreement as shown by his order of

denial of July 10, 1965. Then, after two more years, came the trial with the

complainant having testified on direct examination but not having as yet been fully

cross-examined. At the continuation of the trial set for June 7, 1967 such witness did

not show up. The provincial fiscal moved for postponement. Counsel for petitioner,

however, not only objected but sought the dismissal of the case based on the right of

the accused to speedy trial. Respondent Judge this time acceded, but would likewise

base his order of dismissal, orally given, on the cross-examination of complainant not

having started as yet. Later that same day, respondent Judge did reconsider the order

and reinstated the case, his action being due to its being shown that the cross-

examination of the complainant had already started.

On the above facts, there can be no dispute as to the applicable law. It is not to be lost

sight of that the petition on its face had more than its fair share of plausibility, thus

eliciting an affirmative response to the plea for a writ of preliminary injunction, duly

issued by this Court. For it was all too evident that petitioner could rely on his

constitutional right to a speedy trial. For more than six years the threat of his being

subjected to a penal liability did hang over his head, with the prosecution failing to take

any step to have the matter heard. He did ask that the case be dismissed, but

respondent Judge turned him down. When the trial did at long last take place after two

more years and again postponement was sought as the complainant was not available

for cross- examination, petitioner, as could have been expected, did again seek to put

an end to his travail with a motion for dismissal grounded once more on the

undeniable fact that he was not accorded the speedy trial that was his due. This time

respondent Judge was quite receptive and about time too. The order of dismissal

given in open court had then the effect of an acquittal. For the respondent Judge to

give vent to a change of heart with his reconsideration was to subject petitioner to the

risk of being put in jeopardy once more. Nor could respondent Judge's allegation that

he could do so as he acted under a misapprehension be impressed with the quality of

persuasiveness. The decisive fact was the absence of that speedy trial guaranteed by

the Constitution. This petition then, to repeat, possesses merit.

1. The right to a speedy trial means one free from vexatious, capricious and

oppressive delays, its salutary objective being to assure that an innocent person may

be free from the anxiety and expense of a court litigation or, if otherwise, of having his

guilt determined within the shortest possible time compatible with the presentation and

consideration of whatever legitimate defense he may interpose.

2

The remedy in the

event of a non-observance of this right is by habeas corpus if the accused were

restrained of his liberty, or by certiorari, prohibition, or mandamus for the final

dismissal of the case.

3

In the first Supreme Court decision after the Constitution took effect, an appeal from a

judgment of conviction, it was shown that the criminal case had been dragging on for

almost five years. When the trial did finally take place, it was tainted by irregularities.

While ordinarily the remedy would have been to remand the case again for a new trial,

the appealed decision of conviction was set aside and the accused acquitted. Such a

judgment was called for according to the opinion penned by Justice Laurel, if this

constitutional right were to be accorded respect and deference. Thus: "The

Government should be the last to set an example of delay and oppression in the

administration of justice and it is the moral and legal obligation of this court to see that

the criminal proceedings against the accused came to an end and that they be

immediately discharged from the custody of the law."

4

Conformably to the above ruling as well as the earlier case of Conde v. Rivera,

5

the

dismissal of a second information for frustrated homicide was ordered by the Supreme

Court on a showing that the first information had been dismissed after a lapse of one

year and seven months from the time the original complaint was filed during which

time on the three occasions the case was set for trial, the private prosecutor twice

asked for postponements and once the trial court itself cancelled the entire calendar

for the month it was supposed to have been heard. As pointed out in such decision:

"The right of the accused to have a speedy trial is violated not only when unjustified

postponements of the trial are asked for and secured, but also when, without good

cause or justifiable motive, a long period of time is allowed to elapse without having

his case tried." 6 It did not matter that in this case the postponements were sought

and obtained by the private prosecution, although with the consent and approval of the

fiscal. Nor was there a waiver and abandonment of the right to a speedy trial when

there was a failure on the part of the accused to urge that the case be heard. "Such a

waiver or abandonment may be presumed only when the postponement of the trial

has been sought and obtained [by him]". 7 A finding that there was an infringement of

this right was predicated on an accused having been criminally prosecuted for an

alleged abuse of chastity in a justice of the peace court as a result of which he was

arrested three times, each time having to post a bond for his provisional liberty.

Mandamus to compel the trial judge to dismiss the case was under the circumstances

the appropriate remedy. 8

In Mercado v. Santos, 9 the second occasion Justice Laurel had to write the opinion

for the Supreme Court in a case of this nature, the transgression of this constitutional

mandate came about with petitioner having in a space of twenty months been arrested

four times on the charge of falsifying his deceased wife's will, the first two complaints

having been subsequently withdrawn only to be refiled a third time and thereafter

dismissed after due investigation by the justice of the peace. Undeterred the provincial

fiscal filed a motion for reinvestigation favorably acted on by the Court of First Instance

which finally ordered that the case be heard on the merits. At this stage the accused

moved to dismiss but was rebuffed. He sought the aid of the Court of Appeals in a

petition for certiorari but did not prevail. It was then that the matter was elevated to the

Supreme Court which reversed the Court of Appeals, the accused "being entitled to

have the criminal proceedings against him quashed." It was stressed in Justice

Laurel's opinion: "An accused person is entitled to a trial at the earliest opportunity. ...

He cannot be oppressed by delaying the commencement of trial for an unreasonable

length of time. If the proceedings pending trial are deferred, the trial itself is

necessarily delayed. It is not to be supposed, of course, that the Constitution intends

to remove from the prosecution every reasonable opportunity to prepare for trial.

Impossibilities cannot be expected or extraordinary efforts required on the part of the

prosecutor or the court."

10

The opinion likewise considered as not decisive the fact

that the provincial fiscal did not intervene until an information was filed charging the

accused with the crime of falsification the third time. Thus: "The Constitution does not

say that the right to a speedy trial may be availed of only where the prosecution for

crime is commenced and undertaken by the fiscal. It does not exclude from its

operation cases commenced by private individuals. Where once a person is

prosecuted criminally, he is entitled to a speedy trial, irrespective of the nature of the

offense or the manner in which it is authorized to be commenced."

11

2. More specifically, this Court has consistently adhered to the view that a dismissal

based on the denial of the right to a speedy trial amounts to an acquittal. Necessarily,

any further attempt at continuing the prosecution or starting a new one would fall

within the prohibition against an accused being twice put in jeopardy. The extensive

opinion of Justice Castro in People v. Obsania noted earlier made reference to four

Philippine decisions, People v. Diaz,

12

People v. Abano,

13

People v.

Robles,

14

and People v. Cloribel.

15

In all of the above cases, this Court left no doubt

that a dismissal of the case, though at the instance of the defendant grounded on the

disregard of his right to a speedy trial was tantamount to an acquittal. In People v.

Diaz, it was shown that the case was set for hearing twice and the prosecution without

asking for postponement or giving any explanation failed to appear. In People v.

Abano, the facts disclosed that there were three postponements. Thereafter, at the

time the resumption of the trial was scheduled, the complaining witness as in this case

was absent; this Court held that respondent Judge was justified in dismissing the case

upon motion of the defense and that the annulment or setting aside of the order of

dismissal would place the accused twice in jeopardy of punishment for the same

offense. People v. Robles likewise presented a picture of witnesses for the

prosecution not being available, with the lower court after having transferred the

hearings on several occasions denying the last plea for postponement and dismissing

the case. Such order of dismissal, according to this Court "is not provisional in

character but one which is tantamount to acquittal that would bar further prosecution

of the accused for the same offense."

16

This is a summary of the Cloribel case as set

forth in the above opinion of Justice Castro: "In Cloribel, the case dragged for three

years and eleven months, that is, from September 27, 1958 when the information was

filed to August 15, 1962 when it was called for trial, after numerous postponements,

mostly at the instance of the prosecution. On the latter date, the prosecution failed to

appear for trial, and upon motion of defendants, the case was dismissed. This Court

held 'that the dismissal here complained of was not truly a 'dismissal' but an acquittal.

For it was entered upon the defendants' insistense on their constitutional right to

speedy trial and by reason of the prosecution's failure to appear on the date of

trial.' (Emphasis supplied.)"

17

There is no escaping the conclusion then that petitioner

here has clearly made out a case of an acquittal arising from the order of dismissal

given in open court.

3. Respondent Judge would rely on Cabarroguis v. San Diego

18

to lend support to the

reconsideration of his order of dismissal. The case is not applicable; the factual setting

is different. The order of dismissal set aside in that case arose from the belief of the

court that the crime of estafa was not committed as the liability was civil in character.

At no stage then was there a plea that the accused was denied his right to a speedy