Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

DMI Combat Trauma Manual

Încărcat de

gbarefoot123Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

DMI Combat Trauma Manual

Încărcat de

gbarefoot123Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Combat Trauma Medicine

(CTM)

Student Reference Manual

Deployment Medicine International

2

"These materials may be used only for

Educational and Training Purposes. They

include extracts of copyright works copied

under copyright licenses. You may not copy or

distribute any part of this material to any other

person. Where the material is provided to you in

electronic format you may download or print

from it for your own use. You may not download

or make a further copy for any other purpose.

Failure to comply with the terms of this warning

may expose you to legal action for copyright

infringement."

Deployment Medicine International

3

THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK

Deployment Medicine International

4

COURSE INTENT

Combat Trauma Medicine (CTM)

1. We are medical trainers; we do not establish policy or protocol. We

contribute to these processes through our individual and collective

experience on the field of battle. We are educators and trainers devoted to

the transformation of warriors into warrior healers; the ultimate Warfighter

trained to save lives as well as take them.

2. This course of instruction is designed to address the medical theory and

science behind the special needs of providers in a theatre of war. Our goal

is to augment the skills already given you through your service schools and

other trainingto present you with innovative lessons learned from the

battlefieldto give you additional confidence and knowledge. Our mission

it to train you to be your best when youre best is needed in combat. Our

mission is to train you to save the life of the operator sitting next to you.

3. The DMI CTM (with Live Tissue Training) course addresses the mission of

the operational emergency medical care, remote medical care, prolonged

transport times, unique military wounding and the pre-hospital

environment. In this course we stress both the How and Why of every

combat trauma medical task.

4. We provide a course based on current science and actual experience

specific to the unique environments and resources of operational units to

build on previous non-medical training to specify and train to the treatment

options available to you, the Warfighter, in the combat environment

based on the best academic medical consensus (as a minimum, Tactical

Combat Casualty Care; Basic and Advanced Pre-hospital Trauma Life

SupportCurrent Version), real casualty data, and actual combat

experience to include (as a minimum):

Managing Blood Loss

Airway Management (Non Surgical)

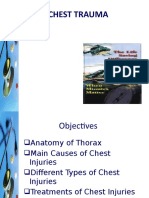

Respiratory Injury Management

Circulation Shock Management

Head Injury and Hypothermia

Deployment Medicine International

5

Casualty Assessment

Medical Ramifications of Blast Injury

Operational Burn Injury Management

Prolonged Care

Advanced Wound Care Management

Pain Management

Maximizing Operational Performance

Field Exercises and Tactically Relevant Scenarios

!

#

$ %

&

Deployment Medicine International

6

5. Training for todays warrior healer (Warfighter) has changed tremendously

in the past decade. Lessons learned in previous conflicts and

requirements for military transformation have been incorporated into this

training. The warrior healer of today is the most technically advanced,

highest trained, and best equipped ever produced by the United States

Militaryour mission is to take your training to the next level.

6. We account for every minute of your training time to maximize your training

experience.

7. Your missions ask questions, contribute, and remain present and

focused. Everything you learn over the next several days will save your

life, or the lives of your comrades should you have to apply what is taught

in this course pay attention.

8. We believe that proper, detailed, and current medical science taught in the

classroom, and reinforced in the Live Tissue Training will bring together

the students performance, knowledge and skills. Therefore, we stress

critical points of operational medicine and lessons learned through case

studies and experience in austere operational environments. We are

dedicated to giving our students the time, training, and experience

necessary for them to remain this Nations vanguard.

9. Classroom didactic lecture, simulator training, and practical exercise (mini

labs) will incorporate the following (as a minimum) course criteria DMI

will add to this the curriculum and include a much broader spectrum to

training for the non-medical operator or combat lifesaver.

Deployment Medicine International

7

COURSE METHOD

The Hybrid Training Model

1. Although not new to the military training regime, performance oriented

training (Task, Condition & Standard) developed in the 1970s and 1980s

was adopted years ago as the teaching mechanism of choice by

Deployment Medicine International (DMI). DMI accepts performance-

oriented training as the baseline standard for all of its training programs.

However, training has evolved in the decades following the inception of

service wide performance oriented training programsespecially in the

field of operational medicine. Therefore, DMI has adopted a four-phased

hybrid-training model, which expands the students learning experience in

two functional areas (performance and retention). We do this to ensure a

definitive result where it is needed mostin battle.

2. The four-phases of the hybrid-training model are:

a. The Classroom Didactic. This will be the lecture portion of your

class, each day, wherein the theory, science, and case studies of

each learning objective are discussed.

b. Practical Exercise, Lab and Simulator training (mannequin,

FAST-1, others). This portion of the training model involves the (in

class) use of simulators, practical demonstrations, videos, hands on

applications and practice using mannequins and other simulators, as

well as the experience of performing (permitted) medical procedures

on each other and on harvested animal tissues (swine tracheas and

ears).

c. Live Tissue Procedures (a half day of medical procedures on

anesthetized animals). The field training exercise training is divided

into two-phases (procedures and scenarios). Phase 1 of the live

tissue portion of your training involves the intensive focus of

performing life-saving battlefield trauma procedures on fully

anesthetized animals. DMI instructors monitor and train you

Deployment Medicine International

8

walking you through each procedure, demonstrating, and then

allowing you and your team to perform the procedure under their

tutelage. DMIs veterinary staff and instructors constantly monitor

your patients (anesthetized swine). Students will assist in this

attention.

d. Live Tissue Scenarios (a half day of hyper-realistic, tactically

relevant scenario based training using anesthetized animals). The

term tactically relevant in Phase II of live tissue training is critical.

You are expected to respond to scenarios that template OIF/OEF

battlefield conditions, and you will be likely to provide care to the

wounded in all three phases of Tactical Combat Casualty Care, (1)

Care Under Fire, (2) Tactical Field Care, and (3) Prolonged Field

Care conditions.

3. Why do we employ the hybrid-training model; why not just teach medicine?

This is a very good question; however, the training mission of DMI is not

only to teach medicine, it is to teach medicine employed in high-threat

environments. This is medicine to save life while all around you; the

enemy will be trying to take your life. To function in this environment

requires the convergence of two elements of the human performance

model: the performance curve, and the retention curve.

4. The performance curve defines your ability to do just that, perform, to see

the patient, access the patient, decide the optimum course of action to

treat the patient and then treatsave life. Many of your

colleagues/operators have adopted the adage, Minutes equal blood, and

blood equals life. The performance curve must peak at the point of

wounding, often under fire (care under fire) or facing imminent danger as

you treat (tactical field care), or during prolonged field care. History

demonstrates that performance curves are high in low stress environments

and markedly low in high stress environments. Therefore, how do you

ensure that your performance curve peaks at the point of wounding? In

addition, what other mechanisms drive this peak performance?

Deployment Medicine International

9

5. The other element of measurement in training is the retention curvethe

ability to recall all of the decision variables related to a life saving task at

the speed of thought, during the worst of circumstancesat the point of

wounding. The classroom didactic, the practical labs and Phase I of the

live tissue training are all designed to build muscle memory, to reinforce

analysis, decision, and right action. Through decades of educational

science, it has been determined that the retention curve is affected

differently than the performance curve in high stress learning

environments. In this instance, the stressors of the classroom environment

build and embed neural patterns affecting muscle memory. These

patterns are called upon in battle; what you know must coalesce at

precisely the right moment as action (performance) if you are to be

effective in battle.

Deployment Medicine International

10

The illustration above (first figure) shows the retention curve and

performance curve coming together past the point of woundingthis

equates to lives lost. The illustration below (second figure) demonstrates

the desired outcome of the emergence of the performance and retention

curves at the point of woundinga condition of training via the hybrid

model.

6. To summarize, in education and training we are dealing with two curves:

performance and retention. In high stress learning environments, the

performance curve decreases; you do not perform at your highest state

when learning complex tasks under high stress conditions. Conversely,

when learning complex tasks under low stress conditions, you perform at a

Deployment Medicine International

11

higher level; however, you retain less. This is the educators dilemma,

especially when training Warfighters to be their best when their best is

needed.

7. The objective is to bring both the retention curve and the performance

curve together, at their peak state, and most critically at the point of

wounding. To do so, requires a hybrid-training model. This is why, we do

not simply teach medicine from a classroom didactic perspective, nor do

we limit your experience to practical exercise, labs and simulatorsto do

so would not provide the level of stress necessary to influence both

learning curves optimally. To achieve the necessary impact, we involve

live tissue in two phases; gradually increasing the environmental training

stressors to a level that increases retention, and to a degree decreases

performance (in the moment). Instructors focus on reinforcing

performance, and retrain where required in the high stress environment

here is where optimal learning occurs.

8. The objective and evidence of this hybrid-training model is increased

performance and situational awareness through rapid recall of all the steps

necessary to perform any given medical task, no matter the complexity.

The hybrid-training model trains our medical personnel at all levels to spin

the decision cycle faster. Medical personnel are trained to see, access,

decide and react under even the most incomprehensible battlefield

environments. Remember, Minutes equal blood, and blood equals life. If

the sights, sounds, tastes, smells and textures of the battlefield are not

unfamiliar to you; if you have to a degree experienced these factorsyou

will perform at a higher ratethis is the objective of this course of study

and practical exercise.

9. DMI employs educational scientists who continually review the manner in

which we present information to our studentsensuring we explore

mechanisms involved in the development of battlefield injury, review

human and animal studies, and conduct constant research on and off the

battlefield. We commit to being hyper-vigilant; collecting and teaching

current information as it pertains to the development of injury and

treatment on the battlefield. While teaching the science and mechanism of

battlefield trauma now, we also pledge our continued focus to the future of

battlefield medicine.

10. This Student Manual is designed to serve you in several ways: a

guide for your classroom didactic portion (lecture), a guide for your

practical exercises in class using simulators and during practical labs. This

manual is not meant to be an exhaustive review, or finite reference; rather

Deployment Medicine International

12

it is an introduction to key principals of the field of combat trauma

medicine. It is meant to be a concise manual for those of you preparing to

enter the global war on terror as medical providers across the spectrum,

from physician to corpsman. The aim of this course is to inspire you with

the theory, the science, and the practical What do I do now? level of

information. You will be inundated with a great deal of information; this

reference manual will serve as a historical source document for your use,

to reflect back on this experience; to use as an azimuth check during your

experience in operational medicine.

11. Do not hesitate to ask the faculty for clarification on any training

objective, or to ask for further reference if it is not contained in the master

reference list provided.

12. As the field of operational medicine progresses, so shall this

reference manual. We attempt to update as necessary.

Deployment Medicine International

13

WHY THIS COURSE?

Dep|oyment Med|c|ne Internat|ona| M|ss|on Statement: - A team of

profess|ona|s comm|tted to prov|d|ng unsurpassed operat|ona| med|ca| tra|n|ng

comp|emented by unmatched d|rect dep|oyed med|ca| support and m|ss|on

or|ented research.

We (DMI) believe that proper, detailed, and current medical science taught

in the classroom, and reinforced in the field exercises will bring together the

students performance and retention curves at the point of wounding.

Therefore, we stress critical points of operational medicine and lessons

learned through case studies and experience in austere environments.

DMI has been training physicians, combat medics, Special Forces soldiers,

conventional war-fighters, and personal protection details including White

House, and law enforcement in operational medicine for over 15 years.

DMI is unique because it is focused on operational medicine.

There is no greater reward for our instructors than to know they made a

difference through the passing of knowledge and thereby saved a life.

Deployment Medicine International

14

COURSE PREREQUISITES

1. Originally, the intended audience for the various DMI training courses was

the Special Operations Forces (SOF) medic, (US Army 18D, US Air Force

Para Rescue, US Air Force Special Operations Medics, US Marine Corps

RECON Corpsmanor equivalent) and key personnel (Physicians,

Physician Assistants, Registered Nurses and Emergency Medical

TechnicianParamedics, Intermediate and Basic, Independent Duty

Corpsman) associated with suchor equivalent.

2. These mission requirements to support the national forces operational

tempo have shifted the prerequisite skill levels necessary to attend CTM to

include basic graduates of the Field Medical Training Battalion corpsman

training (and equivalent), as well as, members of the Local, State and

Federal Law Enforcement Agencies, as well as other Federal Agencies.

3. Essentially, if you have any medical training at all, you will benefit from the

training offered in this course. Even individuals without medical training

have attended this course (non-military) and have expressed a relative

degree of comfort with the material (due primarily to the manner and

mechanism of instruction) and have stated and demonstrated increased

confidence and competence in providing medical aid in emergency trauma

situations.

4. It is entirely the decision of the operational commander to challenge the

student to meet or exceed the commanders training expectations. DMI

will meet the expectations of any operational commander to train their

troops, to augment their skills, improve their confidence and competence

to sustain life at the point of wounding on the battlefield.

5. DMI conducts all training in accordance with the applicable guidelines

established by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care

(CoTCCC), and Pre-Hospital Trauma Life Support PHTLS (Current

Version) and other policy guidance for Combat Trauma Training (CTT) that

includes Live Tissue Training (LTT). This includes ATTP 4-02, OCT 2011,

table 2-2, page 2-3 or other appropriate and current US Army Doctrine.

Deployment Medicine International

15

COURSE COMPLIANCE

Information concerning this training is considered to be of a

sensitive nature. Therefore, the release of any information

pertaining to this course is prohibited without the express written

consent of the Medical Director for Deployment Medicine

International (DMI).

TACTICAL COMBAT CASUALTY CARE (TCCC)

SKILL SETS

Course content is based on skill level.

Course material in this manual is limited to skill sets for deploying

combatants as listed in the tables below.

Supplements to this manual are provided for combat lifesaver,

corpsmen, medics and PJs.

PHTLS FIGURE 24-1 PHTLS 7

TH

EDITION, PAGE 595

Deployment Medicine International

16

FIGURE 24-1 TACTICAL COMBAT

CASUALTY CARE (TCCC) SKILL SETS

ALL DEPLOYING COMBATANTS

SKILL

HEMOSTASIS

APPLY TOURNIQUET

APPLY DIRECT PRESSURE

APPLY BANDAGE

APPLY COMBAT GAUZE

APPLY PRESSURE DRESSING

CASUALTY MOVEMENT TECHNIQUES

AIRWAY

CHIN LIFT/JAW THRUST MANEUVER

NASOPHARYNGEAL AIRWAY

RESCUE BREATHING PATTERN

SIT UP/LEAN FORWARD AIRWAY POSITION

BREATHING

TREAT SUCKING CHEST WOUND

INTRAVENEOUS ACCESS AND IV THERAPY

ASSESS FOR SHOCK

PREVENT HYPOTHERMIA

ORAL AND INTRAMUSCULAR THERAPY

ORAL ANTIBIOTIC

ORAL ANALGESIA

FRACTURE MANAGEMENT

SPLINTING

Deployment Medicine International

17

FIGURE 24-1 TACTICAL COMBAT

CASUALTY CARE (TCCC) SKILL SETS

COMBAT LIFESAVER

SKILL

HEMOSTASIS

APPLY TOURNIQUET

APPLY DIRECT PRESSURE

APPLY BANDAGE

APPLY COMBAT GAUZE

APPLY PRESSURE DRESSING

CASUALTY MOVEMENT TECHNIQUES

AIRWAY

CHIN LIFT/JAW THRUST MANEUVER

NASOPHARYNGEAL AIRWAY

RESCUE BREATHING PATTERN

SIT UP/LEAN FORWARD AIRWAY POSITION

BREATHING

TREAT SUCKING CHEST WOUND

NEEDLE THORACOSTOMY

INTRAVENEOUS ACCESS AND IV THERAPY

ASSESS FOR SHOCK

PREVENT HYPOTHERMIA

ORAL AND INTRAMUSCULAR THERAPY

ORAL ANTIBIOTIC

ORAL ANALGESIA

IM MORPHINE

FRACTURE MANAGEMENT

SPLINTING

TRACTION SPLINTING

Deployment Medicine International

18

FIGURE 24-1 TACTICAL COMBAT

CASUALTY CARE (TCCC) SKILL SETS

CORPSMAN/MEDIC/PJ

SKILL

HEMOSTASIS

APPLY TOURNIQUET

APPLY DIRECT PRESSURE

APPLY BANDAGE

APPLY COMBAT GAUZE

APPLY PRESSURE DRESSING

CASUALTY MOVEMENT TECHNIQUES

AIRWAY

CHIN LIFT/JAW THRUST MANEUVER

NASOPHARYNGEAL AIRWAY

RESCUE BREATHING PATTERN

SIT UP/LEAN FORWARD AIRWAY POSITION

LARYNGEAL MASK AIRWAY (LMA)

SURGICAL AIRWAY

ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION

COMBITUBE

BREATHING

TREAT SUCKING CHEST WOUND

NEEDLE THORACOSTOMY

CHEST TUBE

ADMINISTER OXYGEN

INTRAVENEOUS ACCESS AND IV THERAPY

ASSESS FOR SHOCK

START IV LINE/SALINE LOCK

OBTAIN INTRAOSSEOUS ACCESS

IV FLUID RESUSCITATION

IV ANALGESIA

IV ANTIBIOTICS

Deployment Medicine International

19

ADMINISTER PACKED RED BLOOD CELLS

PREVENT HYPOTHERMIA

ORAL AND INTRAMUSCULAR THERAPY

ORAL ANTIBIOTIC

ORAL ANALGESIA

IM MORPHINE

FRACTURE MANAGEMENT

SPLINTING

TRACTION SPLINTING

ELECTRONIC MONITORING

Deployment Medicine International

20

INTRODUCTION TO OPERATIONAL MEDICINE

A combination of battlefield tactics and immediate casualty care are

essential to mission success and Warfighter survival. This type of

combat casualty care is defined as Operational Medicine.

TRAINING OBJECTIVES:

1. Explain the role of the non-medical Warfighter in combat casualty care.

2. Explain the combat casualty mortality curve.

3. Identify the Warfighters role in participating in a 3-phase approach to tactical

trauma care.

a. Care Under Fire

b. Tactical Field Care

c. Tactical Evacuation Care

d. ADVANCED: Prolonged Field Care

4. Explain the difference between civilian and combat medicine.

5. Explain the M. A. R. C. H. algorithm approach to combat casualty care:

1. Massive Bleeding

2. Airway

3. Respiration

4. Circulation

5. Head injury & Hypothermia

6. Answer all remaining questions regarding the science of combat casualty care.

Deployment Medicine International

21

The focus of this course is on casualty care and how the non-medical

Warfighter must participate in an active role to ensure tactical and

medical objectives are achieved.

Mission success is no longer defined as just achieving the mission

objective but now requires team survival with minimal casualties.

Operational Medicine-Combat Casualty Care

1. Emergency medical care provided in austere and/or remote locations.

2. Casualty care is often secondary to completing the mission.

3. Injuries are primarily penetrating trauma from either fragmentation or gunshot

wounds (GSW).

4. Injuries often occur in a resource-limited environment, where medical supplies

are limited to a Warfighters individual medical kit or a medical providers

rucksack.

5. Evacuation of casualties is often measured in hours requiring strategic planning

of evacuation assets.

6. Casualty care is usually initiated by non-medic Warfighters and continued by

medical providers.

7. Resources and personnel are often overwhelmed with multiple casualties and

limited number of medically trained personnel.

Changing tactics is not a consideration in operational medical care!

Deployment Medicine International

22

THE COMBAT MORTALITY CURVE

1. Following trauma, the chances of a casualty surviving are dependent upon

numerous variables, including the speed at which appropriate medical treatment

is administered. During this session, we will look at the factors that can affect the

chances of a casualty surviving as injuries develop from initial trauma, through

hemorrhage and/or respiration compromise, as well as shock and infection.

2. The Combat Mortality Curve is based on battlefield penetrating trauma (gunshot

wounds, fragmentation). It was derived from research the lethality of weapons

during the Vietnam conflict. This research provides an understanding of the

survivability of combat casualties over an extended timeline of 72 hours. The

Combat Casualty Mortality Curve also provides a comparison between the

survivability of casualties that receive no medical care and those that do.

%

TIME

Deployment Medicine International

23

COMBAT MORTALITY CURVE DATA

Combat Mortality Curve

100%

90%

70%

60%

50%

80%

6 min 1 hr 6 hr 24 hr 72 hr

-Massive Bleeding

-Respiratory

-Head Injury

-Hypothermia

-Wounds

(Infection)

-Self Aid &

Buddy Aid

-Advanced Life

Support (Medic)

-Surgery &

Antibiotics

-Airway

-Circulation

(Shock)

Deployment Medicine International

24

Time Line

1. 0-6 Minutes:

a. Historically 20% of injuries produce an Inevitable Death Rate (IDR)

no matter what medical care they receive. These would include

casualties with major system trauma (heart, brain or spinal). The

IDR has changed very little during the last 200 years. The use of

modern Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) has reduced the rate

from 25% to 20%. There are documented cases of casualties with

non-survivable injuries surviving for up to six minutes. Therefore,

after six minutes, about 80% of the casualties will be alive. Currently

reports show an 18% instantaneous death rate.

2. 6 Minutes-1 Hour

a. By the end of the first hour, another 10% will die from

exsanguinating hemorrhage (large vessels of the extremities and

neck) or from obstruction of the airway (choking) displaced facial

tissue and/or swelling occluding the airway. If a casualty can survive

the first hour, it is highly probable they will make it to the third hour.

Therefore, after 60 minutes, about 70% will survive.

3. 1 Hour-6 Hours

a. By six hours, another 10% will succumb to breathing complications.

Some casualties will show the first signs of shock caused by the

body running on less blood than normal. Although at this stage, they

are unlikely to die from shock alone. After six hours, about 60% will

survive.

4. 6 Hours-24 Hours

a. Between six and 24 hours, deaths occur from shock early on, but

after this condition, they remain relatively stable although dirty

wounds will continue to become more and more infected. After six

Deployment Medicine International

25

hours, the curve is relatively unchanged, about 60% will be alive.

5. 24 Hours-72 Hours

a. Between 24 and 72 hours around 10% of the remaining casualties

are lost due to infection or the lack of surgical intervention.

6. 72 Hours

a. By 72 hours, deaths occur mostly from wound infections. At 72

hours approximately 50% will survive.

Combat Mortality Curve Timeline

Mitigating Factors:

1. Zero to six minutesPrevent injuries. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

and good tactics.

2. Six to sixty minutesSelf Aid & Buddy Aid. Stop the bleeding and open the

airway.

3. One to six hoursSkilled Warfighter and Advanced Life Saving (ALS) level

skills to include decompression of tension pneumothorax, chest tubes, oxygen

therapy, IV access / fluid resuscitation, antibiotics and advanced airway

management.

4. Six hours or moresurgical intervention and additional infection control are

required to show any marked improvements in survival rates beyond the 6-hour

mark.

Deployment Medicine International

26

NOTES:

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Deployment Medicine International

27

WAR CASUALTY STATISTICS

In World War II, 30 percent of the Americans injured in combat died.

In Vietnam, 24 percent of Americans injured in combat died.

In the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, about 10 percent of those injured

have died.

Half of battlefield deaths occur within 30 minutes of wounding, largely

on account of blood loss.

US forces in OIF/OEF are primarily engaged in counterinsurgency

operations within irregular war, in which enemy tactics are primarily

based on terrorism, insurgency and guerilla warfare.

There is no uniformed enemy, no defined front lines or order of battle,

and allegiances can be fluid. As a result, most combat casualties

occur due to ambush or increasingly from the use of improvised

explosive devices (IEDs). IEDs are destructive devices constructed

from homemade, commercial, or military explosive material that are

deployed in ways other than conventional military means. IEDs are

designed to destroy, disfigure, or otherwise interdict military assets in

the field and include buried artillery rounds, antipersonnel mines and

car bombs.

The number of casualties due to explosives has increased relative to

those caused by gunshot.

An analysis of the epidemiology of injuries in OIF/OEF documented

that 81% of all injuries were due to explosions.

(Reference: LTC Philip et al. Epidemiology of Combat Wounds in Operation Iraqi

Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: Orthopedic Burden of Disease.

Journal of Surgical Orthopedic Advances. 2010 Vol 19:1 pg. 2-7)

The use of body armor by US soldiers provides increased protection

to the thorax and to a lesser extent the abdomen and pelvis, and its

effects were first observed in Operation Desert Storm, which saw a

decline in thoracic injuries to 5% compared to 13% seen in Vietnam.

(Reference: Belmont, P.J et al. Incidence and Epidemiology of Combat Injuries

Sustained During The Surge Portion of Operation Iraqi Freedom by a U.S.Army

Brigade Combat Team. J. Trauma. 2010; 68 p.204-210)

Deployment Medicine International

28

WAR CASUALTY STATISTICS

Current Literature: A study from 2011 looking at 2001-2009 combat

statistics shows that

48.6% of mortality secondary to combat wounds was considered

non-survivable.

51.4% of mortality secondary to combat wounds is considered

survivable.

80% of the potentially survivable combat mortalities were

secondary to hemorrhage.

Of the hemorrhage related mortalities the major regions affected

were:

Torso 48%

Extremity 31%

Junctional region; neck, armpit and groin. 21%

Total 100%

Non Survivable cases:

TBI, 83%

Hemorrhage 16%

Other causes 1%

Total 100%

(Reference: Eastridge B.J. et al. Died of wounds on the battlefield: causation and

implications for improving combat casualty care. J. Trauma 2011;71:S4-S8) See

Table 4 and 5 below.

Deployment Medicine International

29

US Military Casualties

Data taken from: Defense Casualty Analysis System

Website: www.dmdc.osd.mil; access date: 8/1/12

Deployment Medicine International

30

Deployment Medicine International

31

Deployment Medicine International

32

Deployment Medicine International

33

Time Line: Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation New Dawn and

Operation Enduring Freedom

Deployment Medicine International

34

What we have seen is the [Interceptor] Body Armor; particularly

what are called the SAPI plates (small arms protective inserts), the

ceramic material plates that go inside the flack (Kevlar) vest that Marines

wear in the field. It's the standard body armor that is now distributed to

everybody; that plus the Kevlar helmets that everyone wears. The result

has been that there has been a decrease in the number of Marines

wounded in the thorax, in the chest and the abdomen-fewer trunk wounds

because of the protective effects of that body armor. And therefore what

wounds that might previously have penetrated the chest or abdomen and

caused fatal or serious injury is not occurring. And that's led to a shift in

the proportion of casualties that we're seeing with extremity injuries and

with head and face and neck injuries.

Capt. Gerard Cox, MC, USN, Director of Medical Programs

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Deployment Medicine International

35

INTRODUCTION TO COMBAT CASUALTY CARE

These medical concepts are specific to battlefield casualty care:

1. Not civilian (EMS) ambulance or hospital care.

2. Involves a combat situation with the possibility of limited available medical

resources or lengthy evacuation times.

3. Concepts in this environment need to remain simple and oriented toward good

tactics.

4. Process begins with the involvement of the Warfighter.

5. If the process doesnt begin or is delayed, more casualties will die.

The Phases of Combat Casualty Care:

1. Consider the management of casualties that occur during combat missions as

being divided into three distinct phases:

2. This approach recognizes a particularly important principle: Perform the

correct intervention at the correct point on the timeline of care.

3. A medically correct intervention at the wrong time in combat may lead to further

casualties, which may be going against good tactics. Remember, the

tactical situation always take precedence over the medical situation.

%'()

*+,)( -.()

/'01.0'2

-.)2, %'()

/'01.0'2

34'05'1.6+

Deployment Medicine International

36

CARE UNDER FIRE PHASE

1. Care Under Fire is the care rendered by the first responder at the scene of the

injury while he and the casualty are still under effective hostile fire. Available

medical equipment is limited to that carried by the Warfighter. Typically,

equipment is made available in personal cargo pouches or provided to

individuals in personal first aid kits.

2. The risk of injury to other personnel and additional injury to the wounded will be

reduced if immediate attention is directed to the suppression of hostile fire.

3. As soon as the Warfighter is able to, keeping the casualty from sustaining

additional injuries is the first major medical objective.

4. Wounded Warfighters who are unable to participate further in the engagement

should lie flat and still if no ground cover is available, or move as quickly as

possible if nearby cover is available. If there is no cover and the casualty is

unable to move himself to find cover, he should remain motionless on the ground

so as not to draw additional fire. A tourniquet that can be applied by the casualty

himself is the most reasonable initial choice to stop major bleeding.

Deployment Medicine International

37

Basic Management Plan for Care Under Fire

1. Return fire and take cover.

2. Direct or expect casualty to remain engaged as a

combatant if appropriate.

3. Direct casualty to move to cover and start self-aid if

able.

4. Try to keep the casualty from sustaining additional

wounds.

5. Casualties should be extricated from burning

vehicles or buildings and moved to places of

relative safety. Do what is necessary to stop the

burning process.

6. Airway management is generally best deferred until the

Tactical Field Care phase.

7. Stop life-threatening external hemorrhage if tactically

feasible:

Direct casualty to control hemorrhage by self-aid

if able.

Use of CoTCCC recommended tourniquet for

hemorrhage that is anatomically amenable to

tourniquet application.

Apply the tourniquet proximal to the bleeding site,

over the uniform, tighten, and move the casualty

to cover.

PHTLS Military Manual Version Seven, Figure 25-1, Page 600

Deployment Medicine International

38

CASUALTY MOBILITY

Casualty mobility is of the utmost importance in the Care Under Fire phase of care.

Casualty drag maneuvers, hasty litters, and drag straps should be used, when needed

to rapidly and safely move a casualty to cover and concealment.

It is imperative that deploying units integrate casualty mobility exercises into their pre-

deployment training.

Consider the benefits and limitations of rigid litters during this phase of casualty care.

Casualty Movement Methods

1. Immobilize casualty

a. Default Drag: Grab any available equipment point

b. Wheelbarrow Drag: Grab both feet facing away from casualty

c. Two Person Drag: Each individual grabs a shoulder strap

d. Drag Strap: Attach a tubular nylon strap to the casualty with a D-ring

e. Multiple Rescuer Carry: Requires minimum of three persons to pick up

casualty at waist

2. Semi-Mobile Casualty

a. Assisted walk: Place the casualty over shoulder and bear the weight of

the injured casualty while moving

b. Firemans Carry: Pick up casualty and carry over shoulder (REQUIRES

CASUALTY TO ASSIST)

Deployment Medicine International

39

CONSIDERATIONS:

1. Understand that various situations will call for different movement techniques.

2. Casualty condition, terrain, available equipment and combat situation will all

play a part in which casualty movement method is used

3. Train on all movement techniques prior to deployment

4. Casualty movement SOPs should focus on simple and reproducible methods

that requires a minimal amount of specialty equipment.

NOTES:

Deployment Medicine International

40

CASUALTY MOBILITY DEVICES:

TALON II LITTER

FOXTROT LITTER

Deployment Medicine International

41

TACTICAL FIELD CARE PHASE

1. Tactical Field Care is the care rendered by the first responder or medic once he

and the casualty are no longer under effective hostile fire. It also applies to

situations in which an injury has occurred, but there has been no hostility.

Available medical equipment is limited to that carried into the field by the team.

Timeline during this phase may vary from a few moments to many hours.

2. This period may consist of only a short opportunity to assess and treat life-

threatening problems due to the need to re-engage threat or it may allow for long

period of casualty management.

3. Tactics, situation and evacuation time will determine the available timeframe.

Deployment Medicine International

42

a. With casualty behind cover/concealment perform an examination of the

casualty and determine the severity of the injuries (See Casualty

Assessment M.A.R.C.H.)

b. Apply the interventions you have been taught and do so knowing that

your situation can quickly change back to Care Under Fire.

c. Be prepared to move and continually communicate with your team.

d. Be aware of your tactical situation.

e. Use your skill and know your time limitations.

f. Get some help!

g. Initiate a TACEVAC request as soon as possible.

4. Take care to reassess earlier interventions:

a. After major movements

b. After re-engaging a threat

c. As soon and as often as the situation allows

d. Go back and look at the interventions you performed while you were under

fire. These actions were performed quickly and may not have been

effective or will not remain effective.

5. Assess the casualty in M.A.R.C.H. order:

Deployment Medicine International

43

a. It is essential to maintain strict adherence to the M.A.R.C.H. algorithm in

this phase of care.

b. As listed above, this phase of care may be short or long in duration. If

wounds are treated out of sequence, life-threatening wounds may remain

untreated prior to TACEVAC.

6. Packaging the casualty for movement or evacuation:

a. The casualty will need to be packaged for protection and evacuation.

Special care will be required when dealing with casualties that are no

longer awake or might lose consciousness during transport or evacuation.

b. Dust and debris during helicopter transport is expected.

c. Casualties that have lost a lot of blood are at risk for hypothermia.

d. Ensure they are covered and kept war.

e. If you are wearing ear protection then you should provide it for your

casualty.

f. Secure arms and legs as necessary-they tend to fall off stretchers during

movement and get banged up during loading casualties on helicopters

and in vehicles.

g. Do not cause further injury!

Deployment Medicine International

44

7. Document the casualtys condition and treatments: Fill out the TCCC

(recommended) Casualty Card (DA Form 7656), or assign a person to do

it for you.

8. PHTLS 7

th

edition Figure 26-17 pg 633

Deployment Medicine International

45

9. Prepare for casualty turnover.

a. Complete an A.T.M.I.S.T. report

i. The A.T.M.I.S.T report is an organized method of turning over

essential casualty information to receiving TACEVAC personnel

and receiving treatment facility.

b. The goal of the A.T.M.I.S.T report is to be organized and concise. This is

essential when turning over casualties to TACEVAC personnel in the

noisy environment of a Landing Zone.

c. Many units also use the A.T.M.I.S.T approach when passing casualty

information over the radio.

10. The A.T.M.I.S.T. report:

Deployment Medicine International

46

!

Age

#

Time of Injury

$

Mechanism of Injury

Examples: Gunshot wound, Blast, Motor Vehicle acciden, blunt

trauma, fall

%

Injuries Sustained

&

Signs and Symptoms

Respiratory rate, pulse rate, casualty feedback

#

Treatments

Describe what you have done and what time the procedure was

done

Organize to M.A.R.C.H or head to toe

Deployment Medicine International

47

Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care

1. Casualties with an altered mental status should be

disarmed immediately.

2. Airway Management

a. Unconscious casualty without airway

obstruction:

Chin lift or jaw thrust maneuver

Nasopharyngeal airway

Place casualty in recovery position

b. Casualty with airway obstruction or impending

airway obstruction:

Chin lift or jaw thrust maneuver

Nasopharyngeal airway

Allow casualty to assume any position that

best protects the airway, to include sitting

up.

Place unconscious casualty in the recovery

position.

If previous measures unsuccessful:

! Surgical Cricothyroidotomy (with

lidocaine if conscious)

3. Breathing

a. In a casualty with progressive respiratory

distress and known or suspected torso trauma,

consider a tension pneumothorax and

decompress the chest on the side of the injury

with a 14-gauge, 3.25 inch needle/catheter unit

inserted in the second intercostal space at the

midclavicular line. Ensure that the needle entry

into the chest is not medial to the nipple line and

is not directed towards the heart.

b. All open and/or sucking chest wounds should

be treated by immediately applying an occlusive

material to cover the defect and securing it in

place. Monitor the casualty for the potential

development of a subsequent tension

pneumothorax.

4. Bleeding

a. Assess for unrecognized hemorrhage and

control all sources of bleeding. If not already

done, use a CoTCCC-recommended tourniquet

application or for any traumatic amputation.

Apply directly to the skin 2-3 inches above

wound.

b. For compressible hemorrhage not amenable to

tourniquet use or as an adjunct to tourniquet

removal (if evacuation time is anticipated to be

longer than 2 hours), use Combat Gauze as the

hemostatic agent of choice. Combat Gauze

should be applied with at least 3 minutes of

direct pressure. Before releasing any tourniquet

on a casualty who has been resuscitated for

hemorrhagic shock, ensure a positive response

to resuscitation efforts (i.e., a peripheral pulse

normal in character and normal mentation of

there is no traumatic brain injury (TBI).

c. Reassess prior tourniquet application. Expose

wound and determine if tourniquet is needed. If

so, move tourniquet from over uniform and

apply directly to skin 2-3 inches above wound. If

tourniquet is not needed, use other techniques

to control bleeding.

d. When time and the tactical situation permit, a

distal pulse check should be accomplished. If a

distal pulse is still present, consider additional

tightening of the tourniquet or the use of a

second tourniquet, side-by-side and proximal to

the first, to eliminate the distal pulse.

e. Expose and clearly mark all tourniquet sites with

the time of tourniquet application. Use an

indelible marker.

5. Intravenous (IV) access

Start an 18-gauge IV or saline lock if

indicated.

If resuscitation is required and IV access is

not obtainable, use the Intraosseous (IO)

route.

6. Fluid resuscitation

Assess for hemorrhagic shock. Altered mental status

(in the absence of head injury) and weak or absent

peripheral pulses are the best field indicators of

shock.

a. If not in shock:

NO IV fluids necessary

PO fluids permissible if casualty is

conscious and can swallow

b. If in shock:

Hextend, 500-ml IV bolus

Repeat once after 30 minutes if still in

shock.

No more than 1000 ml of Hextend

c. Continued efforts to resuscitate must be

weighed against logistical and tactical

considerations and the risk of incurring further

casualties.

d. If a casualty with TBI is unconscious and has no

peripheral pulse, resuscitate to restore the

radial pulse.

7. Prevention of hypothermia

a. Minimize casualtys exposure to the elements.

Keep protective gear on or with the casualty if

feasible.

b. Replace wet clothing with dry if possible.

c. Apply Ready-Heat blanket to torso.

d. Wrap in Blizzard survival blanket.

e. Put Thermo-Lite Hypothermia Prevention

System cap on the casualtys head, under the

helmet.

f. Apply additional interventions as needed and

available.

g. If mentioned gear is not available, use dry

blankets, poncho liners, sleeping bags, body

bags, or anything that will retain heat and keep

the casualty dry.

Deployment Medicine International

48

Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care (Cont)

8. Penetrating Eye Trauma

If a penetrating eye injury is noted or suspected:

a. Perform a rapid field test of visual acuity.

b. Cover the eye with a rigid eye shield (NOT a

pressure patch).

c. Ensure that the 400 mg moxifloxacin tablet in

the combat pill pack is taken, if possible, or that

IV/IM antibiotics are given as outlined below if

oral moxifloxacin cannot be taken.

9. Monitoring

Pulse oximetry should be available as an adjunct to

clinical monitoring. Note: Readings may be

misleading in the settings of shock or marked

hypothermia.

10. Inspect and dress known wounds.

11. Check for additional wounds.

12. Provide analgesia as necessary.

a. Able to fight:

Note: These medications should be carried by

the combatant and self-administered as soon as

possible after the wound is sustained.

Mobic, 15 mg PO once a day

Tylenol, 650-mg bilayer caplet, 2 PO every

8 hours

b. Unable to fight:

Note: Have naloxone readily available

whenever administering opiates.

Does not otherwise require IV/IO access:

! Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate

(OTFC), 800 mcg transbuccally

(a) Recommend taping lozenge-on-a-

stick to casualtys finger as an

added safety measure

(b) Reassess in 15 minutes

(c) Add second lozenge, in other

cheek, as necessary to control

sever pain.

(d) Monitor for respiratory depression.

IV or IO access obtained:

! Morphine sulfate, 5 mg IV/IO

! Reassess in 10 minutes.

! Repeat dose every 10 minutes as

necessary to control severe pain.

! Monitor for respiratory depression

! Promethazine, 25 mg IV/IM/IO every 6

hours as needed for nausea or for

synergistic analgesic effect

13. Splint fractures and recheck pulses.

14. Antibiotics (recommended for all open combat

wounds):

a. If able to take PO:

Moxifloxacin, 400 mg PO once a day

b. If unable to take PO (shock, unconsciousness):

Cefotetan, 2 g IV (slow push over 3-5

minutes) or IM every 12 hours, or

Ertapenem, 1 g IV/IM once a day

15. Burns*

a. Facial burns, especially those that occur in

closed spaces, may be associated with

inhalation injury. Aggressively monitor airway

status and oxygen saturation is such patients

and consider early surgical airway for

respiratory distress or oxygen desaturation.

b. Estimate total body surface area (TBSA) burned

to the nearest 10% using the Rule of Nines.

c. Cover the burn area with dry, sterile dressings.

For extensive burns (>20%), consider placing

the casualty in the Blizzard survival blanket in

the hypothermia prevention kit in order to both

cover the burned areas and prevent

hypothermia.

d. Fluid resuscitation (USAISR Rule of Ten):

If burns are greater than 20% of Total body

Surface Area, fluid resuscitation should be

initiated as soon as IV/IO access is

established. Resuscitation should be

initiated with Lactated Ringers, normal

saline, or Hextend. If Hextend is used, no

more than 1000 ml should be given,

followed by Lactated Ringers or normal

saline as needed.

Initial IV/IO fluid rate is calculated as

%TBSA x 10 ml/hour for adults weighing

40-80 kg, increase initial rate by 100

ml/hour.

If hemorrhagic shock is also present,

resuscitation for hemorrhagic shock takes

precedence over resuscitation for burn

shock. Administer IV/IO fluids per the

TCCC Guidelines in Section 6.

e. Analgesia is accordance with TCCC Guidelines

in Section 12 may be administered to treat burn

pain.

f. Pre-hospital antibiotic therapy is not indicated

solely for burns, but antibiotics should be given

per TCCC guidelines in Section 14 if indicated

to prevent infection in penetrating wounds.

g. All TCCC interventions can be performed on or

through burned skin in a burn casualty.

16. Communicate with the casualty if possible.

Encourage: reassure

Explain care

17. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

Resuscitation on the battlefield for victims of blast or

penetrating trauma who have no pulse, no

ventilations, and no other signs of life will be

successful and should not be attempted.

18. Documentation of Care

Document clinical assessments, treatments

rendered, and changes in the casualtys status on a

TCCC Casualty Card. Forward this information with

the casualty to the next level of care.

PHTLS Military Manual Version Seven, Figure 26-1, Page 613-614

Deployment Medicine International

49

TACTICAL FIELD CARE

'(!&&(&&

!)*+, -./0,

-01+-+2*3

!3 0)*+2 .3

4033567+

!)*+,

+28.8528 .29

*:,+.*3

!29

52*+,1+2*5023

4+,)0,-+;

<2;+, =5,+

Deployment Medicine International

50

TACTICAL EVACUATION CARE

TRAINING OBJECTIVE:

1. Define the Warfighters role in the casualty evacuation phase of combat casualty

care.

2. Explain the importance of initiating a 9-Line.

3. Explain the importance of communication in combat casualty care.

4. Define what information is essential to CASEVAC/MEDEVAC initiation.

5. Explain the principles of managing a casualty collection point.

6. Define triage in modern combat casualty care.

7. Explain considerations unique to CASEVAC/MEDEVAC.

8. Explain proper casualty movement procedures.

9. Explain the considerations associated with the various platforms used in casualty

evacuation.

10. Answer all remaining questions regarding casualty evacuation in combat casualty

care

Deployment Medicine International

51

TACTICAL EVACUATION CARE

1. Combat Tactical Evacuation Care is the care rendered once an aircraft, vehicle

or boat has picked up the casualty.

2. Additional medical personnel and equipment may be available at this stage of

care, which may allow more advanced medical procedures to be performed.

3. Initiate TACEVAC early and with good information.

4. You are responsible for your casualty until you are not.

5. It is also always a good idea to preposition medical supplies if possible. You can

store them in vehicles or other strategic places in case you need them later. This

Deployment Medicine International

52

will allow you to have a cache of medical supplies that are too bulky or heavy for

individuals to be carrying, but are nearby if and when you need them.

CONSIDERATIONS:

1. Standard litters for patient evacuation may not be available for movement of

casualties in the care under fire phase. Consider alternate methods of patient

movement (e.g. dragging the casualty by the web gear or using ponchos, etc.).

2. Keep in mind that if you and the receiving aircraft or vehicle doesnt have the

necessary litters for all of your patients, you can floor load the patients and

secure them with cargo straps. Always defer to the direction of the flight crews

who will guide you in all patients loading and unloading.

3. Consider the use of obscurants (such as smoke) to assist in casualty movement.

4. Vehicles can also be used as shields during evacuation attempts.

5. Once the patient has been transported to the site where evacuation is

anticipated, consider loosening or removing tourniquets and using direct

pressure or direct pressure with hemostatic agents to control bleeding if the

tactical situation allows.

6. Vehicles (ground and air) present unique difficulties with ongoing patient

assessment. In the back of a noisy, dark, turbulent, and windy helicopter, it can

be impossible to perform a basic assessment (e.g. you can only feel for

respirations with a hand on the chest.

7. A patient with a wound that is not properly controlled can bleed in the back of a

Deployment Medicine International

53

dark vehicle without the medical providers knowledge. It is imperative that all

bleeding is absolutely controlled prior to transport.

8. Another consideration of vehicle transport is the threat of hypothermia. In rotary

winged assets you must deal with colder temperatures and high winds

associated with these assets. You must take great care to ensure your patients

are packaged warmly and appropriately.

9. Lastly, remember that more than likely there will be a limited number of medical

providers in any one particular vehicle or asset. You should ensure that as much

medical gear as possible has been given prior to transport. For instance, if there

is one medical provider in the back of a helicopter and he must provide

ventilations for one of the patients, it will be impossible for him to care for and

assess the other patients that are on board. The non-medic may need to

accompany the patient(s) so the medical provider can care for all of the patients.

10. The final phase of casualty care can be the most problematic. Casualties require

a lot of effort to prepare for transport. Insurgent attacks on advanced medical

providers and the vehicles that are utilized are common. If your casualties

require transport by helicopter you must consider the likelihood of an attack

during evacuation. Prior to evacuating your patients, secure a safe landing zone

or extraction point. Establish good communications with the incoming unit(s) and

update them if and when the situation changes.

Deployment Medicine International

54

INITIATING CASUALTY EVACUATION:

.

1. Initiate early. Per the usual operational SOP, only the first three lines of the 9-line

are required to initiate TACEVAC/CASEVAC. Ensure that this information is

available as early as possible.

2. Update the evacuation asset and Command & Control (C2) as the injuries and

situation are better understood or change.

3. Carry a 9-Line request card on your person.

4. Relay: Who, What, When, Where, Why and How many

ACTIONS REQUIRED PRIOR TO CASUALTY EVACUATION:

1. Control bleeding (Have a plan to do so throughout transport).

2. Airway Management (Have a plan for managing the casualtys airway throughout

transport).

3. Ensure respiration assessment is conducted for presence of tension

pneumothorax (See Respiration section).

4. Reassess M.A.R.C.H.

5. Prepare A.T.M.I.S.T. report for each casualty

Age

Time of injury

Mechanism of Injury

Injuries

Signs & Symptoms

Treatments

Deployment Medicine International

55

6. Reassess earlier interventions

7. Casualty eye/ear protection

8. Cross-load mission essential gear

9. Treat for hypothermia

10. Provide pain management as necessary (see page 111 for TCCC update)

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS:

1. Store bulky or heavy equipment and supplies in vehicles and evacuation assets.

These items may include:

Oxygen

Mass casualty kits

High angle rescue equipment

Vehicle extrication equipment

M.A.S.T. pants

Femur traction splint

Ice packs

Cervical collars

Hypothermia Prevention and Burn blankets

Deployment Medicine International

56

EVACUATION PLATFORM CONSIDERATIONS:

1. Ground or Air

2. Number of casualties/condition asset that evacuation assets/s can be taken.

3. Know the medical plan for turning casualties over.

4. Space Available.

5. Different platforms have different passenger ingress routes.

6. Always follow crew chief or flight medics instructions for loading the aircraft.

7. Situational awareness, i.e. landing zone selection, safety, etc.

ENROUTE TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

1. Consider the use of NVG (Night Vision Goggle) compatible lights.

2. Senses may be impaired (wind, turbulent, darkness, etc.) Learn to use feel

instead of listen techniques

3. Not all platforms have a dedicated TACEVAC/CASEVAC medic; you may

become the TACEVAC/CASEVAC medical provider needed to assist.

4. Have all the kit you will need for the flight (plan ahead in case of flight delays).

Deployment Medicine International

57

COMBAT CASUALTY TRIAGE

1. The following is one of many triage systems.

2. Your medical control and casualty evacuation system must support this

system prior to using it.

TRIAGE PRINCIPLES:

1. Do the greatest good for the greatest number of casualties.

2. Employ the available resources in the most efficient way.

3. Triage does not stop, it only repeats.

1. 4. Current triage concepts focus on establishing casualty treatment and

evacuation priority.

4. Focus on updating the Command & Control (C2) element in real time.

5. Plan, prepare and train for triage situations.

TRIAGE CONSIDERATIONS:

1. 1.Triage should:

a. Be used when the number of casualties overwhelms the

medical treatment capabilities, not when medical treatment

providers are not comfortable with the number of casualties.

b. Casualties may be neglected in mass casualty situations.

2. All the casualties will be treated. Triage is focused on the order and priority of

treatment, not which casualties will receive treatment. The exception is casualties

with wounds incompatible with life and those showing no signs of life.

3. Utilize ALL available personnel not currently involved in security operations or

Command & control (C2) efforts.

Deployment Medicine International

58

4. Take into account resupply assets when making decisions regarding how many

medical supplies to use.

TRIAGE CATEGORIES:

1. Immediate: Casualties with high chances of survival who require life-saving

surgical procedures or medical care.

2. Delayed: Casualties who require surgery or medical care, but whose general

condition permits a delay in treatment without unduly endangering the

casualty.

3. Minimal: Casualties who have relatively minor injuries or illnesses and can

effectively care for themselves or be helped by non-medical personnel.

4. Expectant: Casualties with wounds so extensive that even with the benefit of

optimal medical resource application, their survival is unlikely.

CASUALTY COLLECTION POINT OPERATIONS

1. Ensure area is secure.

2. Place all casualties in a manageable configuration. See the Tactical Field Care

section for diagram.

3. Consolidate medical supplies.

4. Triage; Number, Severity, Supplies

5. Ensure Command and control (C2) group is given current reports of casualty

conditions and triage status.

6. Your entire team must understand the principles of CCP operations and the

correct configuration of casualties and resources.

Deployment Medicine International

59

NOTES:

Deployment Medicine International

60

CASUALTY COLLECTION POINT CONFIGURATIONS:

1. TRIANGLE CONFIGURATION

a. Beneficial to distribution of medical supplies and information.

b. Arguable more tactically sound than other methods

c. Casualties should be placed with their heads pointed to the center of the

triangle for easy assessment of their airways.

Deployment Medicine International

61

2. LINEAR CONFIGURATION

a. Easy to organize

b. Allows for easiest priority of movement to TACEVAC/CASEVAC

Deployment Medicine International

62

HEMORRHAGE CONTROL

TRAINING OBJECTIVES:

1. Explain the importance of hemorrhage control in combat casualty care.

2. Define the Warfighters role in hemorrhage control.

3. Describe hemorrhage control concepts.

4. Describe and demonstrate proper direct pressure application.

5. Explain current tourniquet application concepts.

6. Demonstrate the application of tourniquets in DOD circulation.

7. Perform tourniquet practical application lab.

8. Explain correct application of gauze in combat wounds.

9. Demonstrate the application of pressure dressings in DOD circulation.

Deployment Medicine International

63

10. Perform pressure dressing practical application lab.

11. Define hemostatic agent application criteria.

12. Explain the process of applying hemostatic agents.

13. Define hemostatic agent re-application criteria.

14. Explain post application management of wounds treated with hemostatic

agents.

15. Answer all remaining questions regarding hemorrhage control in combat

casualty care.

Deployment Medicine International

64

HEMORRHAGE CONTROL METHODS

PRIMARY METHODS:

1. Direct Pressure

2. Tourniquets

3. Wound Packing

4. Hemostatic Agent

5. Pressure Dressing

ADJUNCT METHODS:

(Not definitive, makes your primary interventions more effective).

1. Indirect pressure

a. Leg pressure points.

b. Arm pressure points.

2. Elevation

3. Anatomical/Rigid Splinting

NOTES:

Deployment Medicine International

65

DIRECT PRESSURE

THE GOAL OF DIRECT PRESSURE TO COMPRESS THE BLEEDING VESSEL

AGAINST THE BONE

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DIRECT PRESSURE:

1. Direct pressure is the usual initial control measure for hemorrhage. Your first

response in most settings is direct pressure. While the tourniquet is being

retrieved from its storage location-apply direct pressure to the wound to control

the bleeding. Use gauze, a blouse or anything that will assist you in applying

direct pressure. If the wound requires the application of a hemostatic agent,

apply direct pressure while you locate the agent and prepare to apply it. Time is

critical and the tactical situation always takes precedence over the medical

situation. Apply direct pressure while assessing the situation and decide the

correct course of action.

2. Palm pressure as opposed to Finger Tip pressure:

a. Diffuse pressure is key, no artery hunting with fingertips.

b. More effective due to the surface area covered.

c. Allows for greater pressure to be applied.

d. Can be maintained for long periods.

e. Fingertip pressure does not provide full contact with wound.

3. Body position is important

a. Arms are straight to reduce fatigue.

b. Shoulders are directly over the wound.

Deployment Medicine International

66

c. Full body weight is required to compress an arterial injury.

4. Packing material is packed into the wound to assist direct pressure.

a. Packing material means gauze, other bandage material or clothing in a

resource limited environment.

b. Packing material allows for more pressure into the wound.

c. Packing material must be in full contact with the wound site to be effective.

5. Hemostatic agents increase the effectiveness of direct pressure, but direct

pressure is critical for the success of hemostatic agents.

6. Direct pressure requires the ground or another hard surface under the casualty

for counter pressure

7. Direct pressure must be dedicated.

a. Do not remove direct pressure to assess the wound. This will invite re-

bleeding. Re-bleeding can be fatal.

b. When transitioning to a pressure bandage, do not release pressure from

the wound.

8. Kneeling on wound site in extreme situations.

a. A knee may be effective if gauze allows transmission of pressure to

wound.

Deployment Medicine International

67

NOTES:

Deployment Medicine International

68

TOURNIQUETS

Extremity Bleeding

1. One of the first considerations for bleeding control

a. The amount of blood loss is an important factor in patients survival, in the

absence of unlimited medical resources (blood, I.V. Fluids, etc.) and the

length of time before the patient will receive definitive treatment

b. The first choice during CARE UNDER FIRE PHASE

c. A bleeding wound requires pressure enough to block the arteries.

d. Tactical situation requires immediate management of blood loss to ensure

the best outcome for the casualty.

2. Lessons from OEF/OIF indicate the use of tourniquets provides better outcome

for casualties.

a. Quickest and easiest way to control extremity hemorrhage

b. Should be used on bleeding extremities initially

NOTES:

Deployment Medicine International

69

Figure 26-4 PHTLS Manual 7

th

Edition pg. 619

FIGURE 26-4 Tourniquet Tips

POINTS TO REMEMBER

Damage to the arm or leg is rare if the tourniquet is left on

less than 2 hours

Tourniquets are often left in place for several hours during

surgical procedures

In the face of massive extremity hemorrhage, it is better to

accept the small risk of damage to the limb than to allow a

casualty to bleed to death.

SIX MAJOR TOURNIQUET MISTAKES

1. Not using the tourniquet when it should be used

2. Using a tourniquet when it should not be used

3. Putting the tourniquet on too proximally

4. Not tightening the tourniquet well enough

5. Not taking the tourniquet off when possible

6. Periodically loosening the tourniquet to allow intermittent

blood flow

DEATH FROM EXANGUINATION

How long does it take to bleed to death from a complete femoral

artery and vein disruption?

Casualties with such an injury are likely to die in about 10

minutes, but some will bleed to death in as little as 3 minutes.

TOURNIQUET APPLICATION

1. Apply without delay for life-threatening bleeding in the Care

under Fire phase

Both the casualty and the corpsmen/medic are in serious

danger while a tourniquet is being applied in this phase

The decision regarding the relative risk of further injury versus

that of bleeding to death must be made by the person

rendering care

NOTE: The life-saving benefit of a tourniquet is far more

pronounced when the tourniquet is applied BEFORE the casualty

Deployment Medicine International

70

has gone into shock from his wound.

2. Non-life-threatening bleeding should be ignored until the

Tactical Field Care phase

3. Apply proximal to the site of hemorrhage over the uniform

during Care Under Fire

4. Tighten the tourniquet until bleeding stops

5. During Tactical Field Care, expose the wound and reapply the

tourniquet directly to the skin 2-3 inches above the bleeding

site

6. Check for distal pulse

7. Tighten the tourniquet or apply a second tourniquet side-by-

side and just proximal to the first as needed to eliminate the

distal pulse

8. Note the time of tourniquet application

REMOVING THE TOURNIQUET

Remove as soon as direct pressure or hemostatic dressings

become feasible and effective, unless the casualty is in shock

or the tourniquet has been on for more than 6 hours

Only a combat medic, or physicians assistant, or a physician

should remove the tourniquets

Do not remove tourniquet if the distal extremity is gone

Do not attempt to remove the tourniquet if the casualty will

arrive at a hospital in 2 hours or less after application

TECHNIQUE FOR REMOVAL

1. Apply Combat Gauze as per instructions

2. Loosen the tourniquet

3. Apply direct pressure for 3 minutes

4. Check for bleeding

5. If no bleeding, apply pressure dressing over the Combat

Gauze

6. Leave tourniquet in place but loose

7. Monitor for bleeding from underneath the pressure dressings

8. If bleeding does not remain controlled, retighten tourniquet,

remove dressings, and expedite evacuation

Deployment Medicine International

71

TOURNIQUET APPLICATION:

1. Ensure tourniquet is as tight as possible prior to engaging the windlass or other

mechanical system.

2. The common problem with tourniquet application is OIF/OEF is that they are not

tight enough.

3. Ensure the tourniquet is secured after it is tightened.

4. The tourniquet should ideally be applied directly to the skin. Remove the uniform

if possible.

5. Use two if necessary:

a. The second tourniquet should ideally be applied above the first if possible.

6. Mark the tourniquet (Time of placement)

NOTES:

Deployment Medicine International

72

STATISTICS ON TOURNIQUET USE

Kragh 2009

91% of tourniquet use in Baghdad was 2 hours or less with low risk of

complications.

Kragh 2008 Baghdad Combat Support hospital)

85% of battle casualties with (one or more) tourniquets had the device applied

before arrival to a facility (prehospital tourniquet)

15% had their first tourniquet applied in the hospital.

Kragh 2009

232 patients; 428 tourniquets were used on 300 limbs

31 of these died due to primary injury; secondary was hemorrhage with no

deaths attributed to tourniquet use

10 patients had tourniquet use AFTER shock and 9 died

222 patients had tourniquets used BEFORE shock and 22 died

No amputations were solely due to tourniquet use

40% of Tourniquets placed pre-hospital are NOT MARKED

Kragh 2011

The pressure in or under the tourniquet is not the key to optimal use.

The key to effectiveness is the occluding the artery,

Users often assume that optimal use requires more force, but optimal use is not

synonymous with effective use; optimal use must include safe use.

More force was associated with misuse.

Deployment Medicine International

73

IDEAL EMERGENCY TOURNIQUET TRAITS

TRAIT IDEAL

Effective Stops distal pulse

Use width Wide compression

Length Fits casualty

Use ease Simple to apply

Weight Low carry weight

Tactical use Care under fire

Cost Inexpensive

Torque control User can limit force

Size small volume

Application speed don quickly

Self-application casualty dons on and off

Open-ended design can route proximal

Don single handedly single-handed

Toughness wears little in use

Doff emergently rapid removal

Stable stays effective

Mechanics internal capacity

Power twist or pump

Placement stays put

Multisetting field to hospital

Replacement can don again

Repair ease few repairs needed

Cleaning ease washes quickly

Storage cube stores densely

Storage life shelf life>10 years

Safety safe use limit

Safe pressure manometer

Monitors pressure, timer

Conformity kept maintains shape

Rugged materials field ready

User expectations preconceptions met

Abridged from Kragh JF. The military emergency tourniquet program's lessons

learned with devices and designs. Mil Med 176:1144 (2011) Table III. Ideal Emergency

Tourniquet Traits

Deployment Medicine International

74

TOURNIQUET REASSESSMENT:

1. Tourniquets applied in the combat environment may become ineffective after the

initial success due to:

a. Casualty movement

b. Shifting of the tourniquet due to placement over uniform

c. Anatomical changes in the shape of the extremity due to movement

d. Physiological changes in the casualty as a result of I.V. fluid treatments

e. Removal or loosening of the tourniquet by the casualty due to pain

2. Reassess the wound for re-bleeding:

a. After making movement

b. After rolling the casualty

c. After engaging an enemy threat

d. After augmenting the casualtys circulatory volume

e. As often as possible

Deployment Medicine International

75

PAIN CONSIDERATIONS:

1. Tourniquets are painful when applied