Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Reliability and Accuracy of Real-Time Visualization Techniques For Measuring School Cafeteria Tray Waste: Validating The Quarter-Waste Method

Încărcat de

mustikaarum0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

21 vizualizări5 pagini...

Titlu original

1-s2.0-S2212267213013373-main

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest document...

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

21 vizualizări5 paginiReliability and Accuracy of Real-Time Visualization Techniques For Measuring School Cafeteria Tray Waste: Validating The Quarter-Waste Method

Încărcat de

mustikaarum...

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 5

RESEARCH

Research and Practice Innovations

Reliability and Accuracy of Real-Time Visualization

Techniques for Measuring School Cafeteria Tray

Waste: Validating the Quarter-Waste Method

*

Andrew S. Hanks, PhD; Brian Wansink, PhD; David R. Just, PhD

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Article history:

Accepted 6 August 2013

Available online 14 October 2013

Keywords:

Plate waste

School lunch

Visual estimation

Weighing waste

Digital photography

Copyright 2014 by the Academy of Nutrition

and Dietetics.

2212-2672/$0.00

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.013

ABSTRACT

Measuring food waste is essential to determine the impact of school interventions on

what children eat. There are multiple methods used for measuring food waste, yet it is

unclear which method is most appropriate in large-scale interventions with restricted

resources. This study examines which of three visual tray waste measurement methods

is most reliable, accurate, and cost-effective compared with the gold standard of indi-

vidually weighing leftovers. School cafeteria researchers used the following three visual

methods to capture tray waste in addition to actual food waste weights for 197 lunch

trays: the quarter-waste method, the half-waste method, and the photograph method.

Inter-rater and inter-method reliability were highest for on-site visual methods (0.90 for

the quarter-waste method and 0.83 for the half-waste method) and lowest for the

photograph method (0.48). This low reliability is partially due to the inability of pho-

tographs to determine whether packaged items (such as milk or yogurt) are empty or

full. In sum, the quarter-waste method was the most appropriate for calculating accu-

rate amounts of tray waste, and the photograph method might be appropriate if re-

searchers only wish to detect signicant differences in waste or consumption of

selected, unpackaged food.

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:470-474.

R

ELIABLY AND ACCURATELY MEASURING TRAY

waste, especially in a school cafeteria, is a key tool to

measuring the impacts of food-behavior interven-

tions. Waste measurement has become even more

important with the new regulations for the 2012 National

School Lunch Program. In the rst couple of weeks of the

2012-2013 school year, reports emerged that students were

wasting large quantities of foods, especially fruits and vegeta-

bles. Although the end result of the regulations is to improve

child nutrition, understanding how much food students

throw away has become a topic of serious interest.

1

In

large-scale studies, it is important to be able to make waste

measurements quickly and accurately in order to reduce

costs to the researchers and hassle for the schools.

Currently, there are multiple useful methods for measuring

tray waste, yet the appropriate method for a study depends

on available resources, research questions, and the specic

setting. Weighing tray waste, the most reliable method, is

highly accurate, but requires a signicant amount of space

and labor, often severely restricting the number of observa-

tions that can be obtained. Visual-measurement methods, on

the other hand, require less labor, space, and can be reliable

and accurate relative to weighing waste. In addition, school

foodservice managers can easily use these visual methods to

better understand the consumption patterns in their own

schools. This study identies one particular on-site visual tray

waste measurement method, the quarter-waste method, as

preferable to two other visual methods due to its reliability,

accuracy, and cost effectiveness.

A large body of literature has been devoted to the use of and

reliability of various methods for measuring the amount

of foods people consume.

2-5

Survey methods, a common

technique,

6,7

suffer from reporting biases. Food frequency

questionnaires are not only costly but respondents

especially childrenhave difculty recalling past food con-

sumption.

8

Manually weighing food waste (weighing method)

is highlyaccurate but costly.

9,10

The weighing method, though,

serves as a baseline gold standard against which alternative

methods are validated.

4

Visual estimation methods

4,11,12

are increasing in popu-

larity because of their ease of implementation and cost

effectiveness. With visual methods, tray waste can be

estimated either on-site

13

or remotely using photo-

graphs.

5,14

Yet little is understood regarding the reliability

and accuracy of these on- and off-site methods relative

to the weighing method, although there is evidence of

high inter-method reliability between visual estimation

methods.

15

*

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercialeShareAlike License, which permits

non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided

the original author and source are credited.

470 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 2014 by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

This study compares three common estimation methods to

the weighing method in school cafeterias. Inter-method and

inter-rater agreement methods were used to identify the

relatively more reliable visual method. In addition, we assess

the level of precision inherent in each method. Finally, in the

context of an intervention study, results from a power test

show which method requires the least number of observa-

tions necessary for detecting a 10% decrease in fruit or

vegetable waste.

METHODS

This study was conducted with approval from the Cornell

University Institutional Review Board. To avoid contamina-

tion of waste measures, students were not informed of the

study before the implementation date. In a corner of the

participating elementary school (kindergarten to grade 5)

cafeteria, a series of tables were linked together. Students

were instructed to place their trays on one end of the tables

when they had completed their meal. From there, trays

would move along the tables in assembly-line fashion. Once a

tray was left at the station, a researcher placed a sticky note

with an identication number on the tray and another

researcher took a photograph of the tray. After being photo-

graphed, another researcher estimated the amount of each

individual item wasted using a visual method that reports

whether none, some, or all of a food item is wasted (half-

waste method). Another researcher estimated tray waste

using a visual method that reports whether none,

1

/

4

,

1

/

2

,

3

/

4

,

or all of a food item is wasted (quarter-waste method). In

both cases, when a packaged product, such as a milk carton

or a yogurt container, was closed and could not be visually

estimated, it was picked up to determine whether empty, full,

or in between.

These two researchers recorded their estimates on sheets

of paper with a list of each possible item next to the tray

identication number. The tray then moved to the nal

location where one of two researchers placed each individual

remaining food item on a standard paper plate and weighed

the amount of each food item remaining. In order to obtain

inter-rater reliability measures for the half-waste and

quarter-waste methods, an additional researcher measured

tray waste on a random sample of the trays using either the

half-waste (n26) or quarter-waste method (n27). Items

from students who did not purchase a full school lunch were

not measured.

Individuals measuring tray waste were internal to the

research team. Those conducting the visual-estimation

methods either had previous experience measuring tray

waste or were trained using protocols and photographed ex-

amples. Before the lunch period, researchers assigned to

measure waste visually examined a serving of each food item

offered and weighed ve complete and uneaten servings of

eachitemtogenerate anaverageweight per serving. Container

and cartonweights were also taken for items such as carrots or

salad, which were served in small plastic cups, or milk and

juice, which were served in cartons. These procedures served

two purposes. First, researchers using the visual-estimation

methods knew the size of a standard serving and used this to

estimate tray waste. Second, average serving weights were

used to generate estimates of the grams wasted for each of the

visual-estimation techniques.

Several days after the on-site measurements were

completed, a researcher used a 10% scale to estimate waste

appearing in the tray photographs (none, 0.10, 0.20, . . ., 0.90,

or all wasted). For inter-rater reliability, a separate researcher

used the same method to estimate tray waste in 40 randomly

selected photographs.

Data and Analysis

Tray waste was collected for 197 total trays. This was the total

number of students who received a school lunch that day.

The menu for the day included four entre items: chicken

nuggets, chicken strips (served once the nuggets were gone),

peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and yogurt. Fruit options

included applesauce and oranges. Vegetable options included

green beans, salad, and carrots. Grain choices included rice

and a bagel. Students could also choose a cookie, a package of

sunower seeds, or a small bag of chips. Beverage options

included fat-free milk, 1% white milk, 1% chocolate milk, or-

ange juice, and apple juice.

Inter-method and inter-rater reliability were measured

using methods used in previous studies.

16,17

Specically,

correlation coefcients of amounts wasted were calculated

to compare the weighing method and the three visual-

estimation methods, providing an inter-method reliability

score. In addition, correlations of measured waste between

researchers, but for the same method, were calculated as an

inter-rater reliability score. As a second test of inter-method

reliability, correlations between waste measured using the

weighing method and the three visual-estimation techniques

were calculated for each food item offered.

To test accuracy in waste measures, t tests were used to

estimate the difference in measured waste between the

weighing method and the three visual-estimation methods.

This comparison was carried out for each food item offered in

the cafeteria that day. Finally, power tests were used to

calculate the number of observations necessary to detect a

10% decrease in waste for the weighing method and the three

visual methods. In these power tests, average waste for all

fruits and all vegetables, as measured with the weighing

method, are used. Because intervention studies rely on

before-and-after measures, the power tests are based on in-

dependent two-sample t tests with equal sample sizes and

equal standard deviations assumed both before and after the

waste decrease.

RESULTS

To demonstrate the reliability, accuracy, and statistical power

for each visual estimation technique, results from these

methods are reported and compared with the weighing

method.

Reliability

Reliability measures (correlations) reveal how closely each

visual methods waste measures compare with the weighing

method. The quarter-waste method has a reliability measure

of 0.90 (P<0.001) and the half-waste and photograph

methods have reliability measures of 0.83 (P<0.001) and 0.48

(P<0.001), respectively. Low reliability for the photograph

method is due to difculty in estimating waste in milk and

juice cartons as well as other foods that are served in pack-

ages or containers that obstruct the view of the remaining

RESEARCH

March 2014 Volume 114 Number 3 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 471

food. Inter-rater reliability indicates high internal consistency

for the quarter-waste method (0.95; P<0.001) and half-waste

method (0.88; P<0.001), but relatively lower internal con-

sistency for the photograph method (0.57; P<0.001). Again,

this might be because of the inability to see inside of cartons,

packages, and containers, thus severely biasing visual waste

estimates.

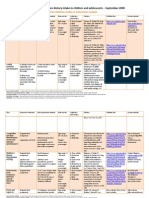

Inter-method reliability for specic foods items (Table 1)

shows that the photograph method is least reliable for foods

in packages and cartons (milk, juice, sunower seeds, and

chips). Specically, reliability measures from the photograph

methods were essentially no different from zero for chips and

sunower seeds, and were very low for chocolate milk. On

the other hand, reliability results for the quarter-waste

method were 80% or better for 15 of 19 food items

compared with 12 of 19 items for the half-waste method.

Accuracy in Waste Measures

Reliability results provide strong evidence that relative to the

half-waste and photograph methods, the quarter-waste

method most reliably generates waste measures similar to

the weighing method. In the next set of tests, differences in

waste measured between the weighing method and the vi-

sual methods are all compared to identify which visual

method is most accurate in terms of a linear difference.

Average waste per food item measured by the photograph

method is statistically different from that given by the

weighing method for chicken nuggets (P<0.001), chicken

strips (P<0.01), applesauce (P<0.01), rice (P<0.05), chips

(P<0.01), and apple juice (P<0.05). Waste measures for the

half-waste and quarter-waste methods are statistically

different for rice (P<0.05), and the quarter-waste method

reports a statistically different amount of green bean waste

(P<0.01). Of the three methods, the photograph method

proved to be the least accurate visual method.

Statistical Power

Although the proximity in waste measure provides evidence

for the ability of the visual methods to generate waste mea-

sures similar to those reported by the weighing method,

variability in within-method measurement could affect the

methods ability to detect a difference in the presence of an

intervention. Greater variability decreases statistical power

and requires larger sample sizes for detecting differences.

Sufciently large sample sizes can be difcult to obtain,

especially in a school cafeteria setting, when resources are

limited.

Fruit and vegetable waste generated from the weighing

method were averaged over the items in the two food groups.

Standard deviations of fruit and vegetable waste for each

measurement method were calculated (Table 2). With these

average waste measures, a 10% reduction in waste was

calculated, and power tests were used to determine the

necessary sample size to declare this difference as statistically

signicant. These tests show that the weighing method re-

quires the least number of observations, as expected, for

detecting a difference. Interestingly, the photograph method

is next and requires 1,400 observations for detecting a 10%

decrease in fruit waste and 625 for detecting a 10% decrease

in vegetable waste. The quarter-waste- and half-waste

methods require the most observations for detecting a 10%

decrease in fruit and vegetable waste.

DISCUSSION

There are various methods used for collecting tray waste in

school intervention research. These methods vary in terms of

time, accuracy, implementation difculty, and manpower

requirements. An appropriate choice of methods depends

on the researchers needs and resources; therefore, identi-

fying the most appropriate method for the situation is an

important resource consideration.

In this study, the time to weigh tray waste took approxi-

mately 30 seconds per tray. Measuring tray waste using the

Table 1. Inter-method reliability of visual

waste-measurement methods: Observations from

197 trays in a school cafeteria

a

Food item

Methods

Half-

waste

Quarter-

waste Photograph

Entres

Chicken nuggets 0.93*** 0.98*** 0.95***

Chicken strips 0.82*** 0.89*** 0.85***

Peanut butter and jelly 0.85** 0.93*** 0.83*

Yogurt 0.97*** 0.97*** 0.65

Fruit

Applesauce 0.91*** 0.91*** 0.78***

Orange 0.53** 0.74*** 0.55**

Vegetables

Carrots 0.93*** 0.88*** 0.72***

Green beans 0.72*** 0.85*** 0.90***

Salad 0.80*** 0.76*** 0.71**

Grains

Bagel 0.69 0.98*** 0.38

Rice 0.82*** 0.90*** 0.89***

Snacks

Chips 0.99*** 0.93*** 0.08

Cookie 1.00*** 0.15

Sunower seeds 0.21 0.32 0.16

Beverages

Fat-free milk 0.57* 0.67** 0.16

1% milk 0.88*** 0.94*** 0.12

Chocolate milk 0.87*** 0.93*** 0.47***

Apple juice 0.78*** 0.89*** 0.72***

Orange juice 0.92*** 0.93*** 0.73***

a

Inter-method reliability scores are calculated as correlations between the amount

wasted as measured by the weighing method and the amount wasted as measured by

three visual-estimation methods: half-waste, quarter-waste, and photograph methods.

*P<0.05.

**P<0.01.

***P<0.001.

RESEARCH

472 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS March 2014 Volume 114 Number 3

half-waste and quarter-waste methods takes approximately 4

to 5 seconds per tray. The photograph method requires that

each tray be labeled, which takes <1 second per tray, and

then photographed, which requires an additional 1 to 2 sec-

onds. Then, visually estimating tray waste using digital im-

ages takes 4 to 5 seconds per tray, so the photograph method

requires approximately 2 more seconds per tray, relative to

the on-site visual methods. Visual-estimation techniques

take approximately one fth of the time required by the

weighing method, but vary in their reliability and accuracy.

When compared with the half-waste and photograph

methods, the quarter-waste method was found to be the

most reliable method. The quarter-waste method was more

accurate than the photograph method, especially when

measuring waste for foods that were prepackaged or bever-

ages served in containers. Indeed, the photograph method

both under- and overestimated waste for various items, but

consistently overestimated waste when the food or beverage

was in a package or container. Neither the half-waste or

quarter-waste methods generated consistently biased waste

measures. Unless additional care is taken to facilitate visual

estimation of tray waste for packaged foods or beverages,

the photograph method will not generate reliable waste

estimates for these items.

Interestingly, power tests show that the photograph

method requires fewer observations for detecting a differ-

ence in total fruit or vegetable waste. This is because the

photograph method used smaller increments for measuring

waste, thus reducing deviation in measurements. If the

research goal is to detect a difference in tray waste, then the

photograph method requires fewer observations. On the

other hand, if the research goal is to generate an accurate

(without bias) measure of tray waste, then the quarter-waste

method is a cost-effective, reliable, and accurate visual

method.

In light of these ndings, it is important to note limitations

to the study. First of all, tray waste measures were collected

for 1 day at one school only, which limited the types of foods

measured. The selection of fruits and vegetables offered in

cafeterias, however, is typically limited. Yet, the lowreliability

of the photograph method for foods served in packages and

cartons suggests that even with multiple days, the reliability

will not improve substantively. Notably, all but three of the

food items in this study were served in packagesyogurt,

chips, and sunower seedsand such foods vary from cafe-

teria to cafeteria. Milk and juice, however, are universally

served in cartons, and accurate waste measures are difcult

to obtain via photographs.

Second, photographs of trays were not taken before the

student sat down to eat. Relying on the post-consumption

photograph only limits the researchers ability to identify

what items were on the tray, especially if all of an item were

eaten and left little trace, or if items were served in similar

containers, such as salad and carrots. Taking pre-photographs

of students trays, though, requires more resources and

additional coordination in order to match the before and after

photographs. Although this may not be too difcult, it might

be prohibitive for foodservice directors interested in

measuring tray waste in their own cafeterias.

Third, because accurate waste measures are a keyelement in

intervention studies, it is important to identify ways to miti-

gate biases in student behavior stemming from researcher

presence inthe cafeteria. Regardless of the methodusedhalf-

waste, quarter-waste, photograph, or weighingall are

obtrusive and potentially generate biases in behavior. This

impact can be limited in the following ways: researchers

should establish a measurement station in an obscure location

in the cafeteria where students leave their trays; inquisitive

students can be given a general answer, such as We are col-

lecting information about your cafeteria, when they inquire

about the researchers presence; and when space is limited,

researchers are instructed to stand close enough to the trash

receptacles to see what students are throwing away, but far

enough away to remain relatively inconspicuous.

A key contribution of this research is showing that there

are visual approaches that come close to approximating the

accuracy of the gold standard of weighing every item.

Notably, observation methodsparticularly the quarter-

waste methodwere substantially more reliable and accu-

rate than the photograph method. This might raise the

question whether an even more granular estimation

methodsuch as a decile approachwould be even better.

Results in this study, however, show that a more granular

estimation method comes with costs in both accuracy and

reliability. Specically, reliability from a decile-waste method

was an unacceptable 0.57 compared with a reliability of 0.95

for the quarter-waste method.

CONCLUSIONS

Identifying an appropriate method for measuring tray waste

in school cafeteria or other foodservice intervention research

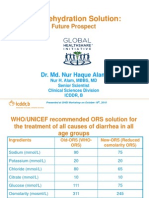

Table 2. Comparing the statistical power of

waste-measurement methods: Observations from

197 trays in a school cafeteria

Standard

deviation

Sample size

required to detect

a 10% decrease

in waste

a

Test

power

Mean fruit

waste23.7 g

Weigh 33.70 1,100 0.95

Half-waste 42.84 1,780 0.95

Quarter-waste 40.03 1,550 0.95

Photo 37.91 1,400 0.95

Mean vegetable

waste25.8 g

Weigh 24.55 500 0.95

Half-waste 32.01 850 0.95

Quarter-waste 35.71 1,050 0.95

Photo 27.53 630 0.95

a

The test is based on an independent two-sample t test with equal standard deviation

and equal sample size for both samples. If the sample size necessary to detect a dif-

ference is equal to 1,000, then in this comparison, 500 tray waste observations must be

gathered both before and after the intervention.

RESEARCH

March 2014 Volume 114 Number 3 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 473

is not a trivial matter. In this study, three visual-estimation

methods were compared with weighing tray waste, which

is the most accurate yet time-consuming method. Results

from this study show that the visual method in which waste

is measured in quarter-waste incrementsnone,

1

/

4

,

1

/

2

,

3

/

4

,

or all wastedis the most reliable of the visual me-

thods studied. In addition, it is just as accurate as a method

in which waste is measured in half-waste incrementsnone,

1

/

2

, or all wastedand more accurate than a photograph

method, in which a researcher visually observes tray

waste using photographs and estimates waste in 10%

incrementsnone, 0.1, 0.2, . . ., 0.9, or all wasted.

With an increasing number of researchers testing

interventions in school lunches, standards for reliable and

accurate measures of consumption and waste have become

increasingly important to providing policy advice. Increases

in fruit and vegetable waste have been of great concern since

the introduction of new school lunch guidelines requiring a

fruit or vegetable to be included in any meal receiving a

reimbursement. With school cafeteria managers concerned

about what their students are wasting, how much is being

wasted, and how to decrease that waste, the quarter-waste

method is an extremely simple tool they can use to mea-

sure waste on their own. In addition, this same method can

be used in university dining halls, restaurants, and other

dining establishments for detecting waste patterns among

diners and empowering managers of these establishments to

nd ways for cutting waste and improving their bottom line.

References

1. Just DR, Price J. Default options, incentives and food choices: Evi-

dence from elementary-school children [published online ahead of

print May 28, 2013]. Publ Health Nutr. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/

S1368980013001468.

2. Burghardt J, Devaney B, Gordon A. The school nutrition dietary

assessment study: Summary of ndings (53-3198-0-16). US

Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. 1993.

Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. website. http://naldc.nal.usda.

gov/download/46370/PDF. Accessed January 25, 2013.

3. Young LR, Nestle M. Portion sizes in dietary assessment: Issues and

policy implications. Nutr Rev. 1995;53(6):149-158.

4. Buzby J, Guthrie J. Plate waste in school nutrition programs: Report

to congress. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Ser-

vice. 2002. Electronic Publications from the Food Assistance &

Nutritional Research Program website. http://www-test.ospi.k12.wa.

us/Finance/pubdocs/PlateWasteInSchoolNutrition.pdf. Accessed

January 25, 2013.

5. Swanson M. Digital photography as a tool to measure school

cafeteria consumption. J Sch Health. 2008;78(8):432-437.

6. Bingham S, Gill C, Welch A, et al. Comparison of dietary assessment

methods in nutritional epidemiology: Weighed records v. 24 h re-

calls, food-frequency questionnaires and estimated-diet records. Br J

Nutr. 1994;72(4):619-643.

7. Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford

University Press; 1998.

8. Lebersorger S, Schneider F. Discussion on the methodology for

determining food waste in household waste composition studies.

Waste Manage. 2011;31(9):1924-1933.

9. Comstock E, St Pierre R, Mackiernan Y. Measuring individual plate

waste in school lunches. Visual estimation and childrens ratings

vs. actual weighing of plate waste. J Am Diet Assoc. 1981;79(3):

290-296.

10. Williamson DA, Allen R, Martin PD, Alfonso AJ, Gerald B, Hunt A.

Comparison of digital photography to weighed and visual estimation

of portion sizes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(9):1139-1145.

11. Shankar A, Gittelsohn J, Stallings R, et al. Comparison of visual esti-

mates of childrens portion sizes under both shared-plate and

individual-plate conditions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(1):47-52.

12. Williams C, Bollella M, Strobino B, et al. Healthy-Start: Outcome of

an intervention to promote a heart healthy diet in preschool

children. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21(1):62-71.

13. Hanks AS, Just DR, Wansink B. Smarter Lunchrooms can address new

school lunchroom guidelines and childhood obesity. J Pediatr.

2013;162(4):867-869.

14. Martin C, Newton R, Anton S, et al. Measurement of childrens food

intake with digital photography and the effects of second servings

upon food intake. Eat Behav. 2007;8(2):148-156.

15. Parent M, Niezgoda H, Keller HH, Chambers LZ, Daly S. Comparison

of visual estimation methods for regular and modied textures:

Real-time vs digital imaging. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(10):

1636-1641.

16. Oza-Frank R, Hade EM, Conrey EJ. Inter-rater reliability of Ohio

school-based overweight and obesity surveillance data. J Acad Nutr

Diet. 2012;112(9):1410-1414.

17. Richter SL, Vandervet LM, Macaskill LA, Salvadori MU, Seabrook JA,

Dworatzek PDN. Accuracy and reliability of direct observations of

home-packed lunches in elementary schools by trained nutrition

students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(10):1603-1607.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

A. S. Hanks is a postdoctoral research associate, B. Wansink is a John S. Dyson Professor of Marketing, and D. R. Just is an associate professor, all at

the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Address correspondence to: Andrew S. Hanks, PhD, Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, 112

Warren Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853. E-mail: ah748@cornell.edu

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conict of interest was reported by the authors.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

All research was funded by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) grant 59-5000-0-0090, which established Cornell Universitys Center for

Behavioral Economics in Child Nutrition Programs. The USDA played no other role in the conduct of the study. The Cornell University Institutional

Review Board approved the design of this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Adam Brumberg, Kirsikka Kaipainen, and Sudy Majd for comments and assistance in conducting the study and drafting this

article. We also wish to thank Julia Hastings-Black and Kelsey Gatto for their editorial assistance. Finally, we express appreciation to participants

who attended the 2012 Annual Conference of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior for their comments.

RESEARCH

474 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS March 2014 Volume 114 Number 3

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Middle School Cafeteria Food Choiceand Waste Priorto ImplementationDocument13 paginiMiddle School Cafeteria Food Choiceand Waste Priorto ImplementationL GeckoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Web-Buffet - Development and Validation of An Online Tool To Measure Food ChoiceDocument10 paginiThe Web-Buffet - Development and Validation of An Online Tool To Measure Food ChoiceFernando RibeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- School Lunch Acceptance Study & Marketing Plan PowerPoint PresentationDocument25 paginiSchool Lunch Acceptance Study & Marketing Plan PowerPoint Presentationdsaitta108Încă nu există evaluări

- Comstock - Using A Visual Plate Waste Study To MonitorDocument3 paginiComstock - Using A Visual Plate Waste Study To MonitorAni 'Kristi'asihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leite Et Al 2012Document7 paginiLeite Et Al 2012Paula MartinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of A Consumer Behavior Intervention To Improve Healthy Food Purchases From Online Canteens PDFDocument10 paginiCluster Randomized Controlled Trial of A Consumer Behavior Intervention To Improve Healthy Food Purchases From Online Canteens PDFHUYỀN BÙI THỊÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preventing Chronic Disease - Cal Poly Dining Environment NEMS - Final-2Document10 paginiPreventing Chronic Disease - Cal Poly Dining Environment NEMS - Final-2Mustang NewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter IiDocument3 paginiChapter IiAsyana Allyne B DueñasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Validation of A Newly Automated Web-Based 24-HourDocument11 paginiValidation of A Newly Automated Web-Based 24-Hourイアン リムホト ザナガÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Multiple Food TestDocument9 paginiThe Multiple Food TestKlausÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Brief An Objective Measure of Nutrition Facts Panel Usage and Nutrient Quality of Food ChoiceDocument6 paginiResearch Brief An Objective Measure of Nutrition Facts Panel Usage and Nutrient Quality of Food Choicenovi diyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- School Lunch Acceptance Study Marketing Plan Powerpoint PresentationDocument25 paginiSchool Lunch Acceptance Study Marketing Plan Powerpoint Presentationapi-319420031Încă nu există evaluări

- Diet Assessment ToolDocument3 paginiDiet Assessment Toolme_sushmadahalÎncă nu există evaluări

- RRL RRS Chapter 2Document5 paginiRRL RRS Chapter 2Asyana Allyne B DueñasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selecting Items For A Food Behavior Checklist For A Limited-ResourceaudienceDocument15 paginiSelecting Items For A Food Behavior Checklist For A Limited-ResourceaudienceAnisa MuliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Megan Rollo ThesisDocument10 paginiMegan Rollo Thesistinamclellaneverett100% (1)

- PosterDocument1 paginăPosterapi-307248648Încă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Food Waste Management System As PracticedDocument4 paginiEffectiveness of Food Waste Management System As PracticedJia Mae Sapico ApantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rotulo Nutri-Score Avaliacao RotuloDocument31 paginiRotulo Nutri-Score Avaliacao RotuloFátima DuarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proposed Programme of Research For 'Masters by Research' ApplicationDocument6 paginiProposed Programme of Research For 'Masters by Research' ApplicationSophia SalvatoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Measuring household food wasteDocument14 paginiMeasuring household food wasterobiah khoirÎncă nu există evaluări

- 23 !!!!!!!!cks096Document6 pagini23 !!!!!!!!cks096Giuseppe Peppuz VersariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Khush RM FinalDocument40 paginiKhush RM FinalParinShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- BurrowsDocument10 paginiBurrowsBenja NGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food AccountDocument6 paginiFood AccountanaraudhatulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploration of School Meal Food Service Management: A Case Study of A Full-Day SchoolDocument8 paginiExploration of School Meal Food Service Management: A Case Study of A Full-Day SchoolIJPHSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acceptability of Canistel Fruit Flour CookiesDocument8 paginiAcceptability of Canistel Fruit Flour CookiesfasdgahfadisfvhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Athletes Food Choices During CompetDocument15 paginiEvaluation of Athletes Food Choices During CompetRara RabiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resources, Conservation & Recycling: Full Length ArticleDocument8 paginiResources, Conservation & Recycling: Full Length Articlediana.alyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Janani, Chapter 3Document5 paginiJanani, Chapter 3kimbertsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Safety Practices of Canteen Food Handlers in Bacolod CityDocument26 paginiFood Safety Practices of Canteen Food Handlers in Bacolod CityAya BolinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scope and DelimitationDocument1 paginăScope and DelimitationHeaven Leigh SorillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Look Into The Food Preferences of Marketing Management Students of San Pedro College Inc.Document48 paginiA Look Into The Food Preferences of Marketing Management Students of San Pedro College Inc.Angelyn Nicole MagsanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Validated Survey To Measure Household Food WasteDocument9 paginiA Validated Survey To Measure Household Food Wasteraluka120Încă nu există evaluări

- Cafeteria Assessment For Elementary Schools (CAFES) : Development, Reliability Testing, and Predictive Validity AnalysisDocument16 paginiCafeteria Assessment For Elementary Schools (CAFES) : Development, Reliability Testing, and Predictive Validity AnalysisR IrnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15 Advanced Menu AB 1Document11 pagini15 Advanced Menu AB 1Roy CabarlesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article ABP 2 Primer Torn (2020-21)Document9 paginiArticle ABP 2 Primer Torn (2020-21)Rachel Sotolongo PiñeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poster Session: Food/Nutrition Science Education Management Food Services/Culinary ResearchDocument1 paginăPoster Session: Food/Nutrition Science Education Management Food Services/Culinary ResearchHaffiz RizalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adolescent eating habits in Islamabad schoolsDocument7 paginiAdolescent eating habits in Islamabad schoolsFouzia GillÎncă nu există evaluări

- GgyyDocument8 paginiGgyyIra BerunioÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study of Knowledge, Attitude & Practice On Food Safety Among The Food Handlers in The Restaurants of Kalyani, District: NadiaDocument13 paginiA Study of Knowledge, Attitude & Practice On Food Safety Among The Food Handlers in The Restaurants of Kalyani, District: NadiaIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0956053X17305135 MainDocument14 pagini1 s2.0 S0956053X17305135 MainGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smartphone. ValidationDocument11 paginiSmartphone. ValidationManal Haj HamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumption Habits of School Canteen and Non-Canteen Users Among Norwegian Young Adolescents: A Mixed Method AnalysisDocument12 paginiConsumption Habits of School Canteen and Non-Canteen Users Among Norwegian Young Adolescents: A Mixed Method AnalysisShien SantiagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poster Session: Food/Nutrition Science Education Management Food Services/Culinary ResearchDocument1 paginăPoster Session: Food/Nutrition Science Education Management Food Services/Culinary ResearchFelia Prima WefianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutritional Status, Food Consumption at Home, and Preference-Selection in The SchoolDocument5 paginiNutritional Status, Food Consumption at Home, and Preference-Selection in The SchoolRahmiwulandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- 19 - Nutrients-13-01319-V2Document11 pagini19 - Nutrients-13-01319-V2Giuseppe Peppuz VersariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutritional and Behavioral Determinants of Adolescent Obesity: A Case - Control Study in Sri LankaDocument6 paginiNutritional and Behavioral Determinants of Adolescent Obesity: A Case - Control Study in Sri LankaStefannyAgnesSalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Martins Et Al 2013 - JNEBDocument9 paginiMartins Et Al 2013 - JNEBPaula MartinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- FWBQ Preprint 23-04-22Document46 paginiFWBQ Preprint 23-04-22Lenny SegubienseÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Research ProposalDocument6 paginiMy Research ProposalJoseph AddoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Inc Research PaperDocument7 paginiFood Inc Research Paperafeaudffu100% (1)

- Physical Activity in Preschool Children: Comparison Between Montessori and Traditional PreschoolsDocument6 paginiPhysical Activity in Preschool Children: Comparison Between Montessori and Traditional PreschoolsRubén LópezÎncă nu există evaluări

- To Whom Correspondence Should Be Addressed - E-Mail: Dahong@md - Okayama-U.ac - JPDocument7 paginiTo Whom Correspondence Should Be Addressed - E-Mail: Dahong@md - Okayama-U.ac - JPdiana.alyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of A Preschool Nutrition Education Program Based On Multiple IntelligenceDocument4 paginiEvaluation of A Preschool Nutrition Education Program Based On Multiple IntelligenceRania SolimanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scot Dietary Assessment MethodsDocument17 paginiScot Dietary Assessment MethodsnadiaayudÎncă nu există evaluări

- MsafDocument7 paginiMsafShikya AbnasÎncă nu există evaluări

- s12966 019 0798 1Document15 paginis12966 019 0798 1hey rizkiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrients: Ffect of Supportive Implementation of HealthierDocument16 paginiNutrients: Ffect of Supportive Implementation of HealthierGabriel Torres BenturaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines for Assessing Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes and PracticesDe la EverandGuidelines for Assessing Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes and PracticesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dietary Fiber Intake in Early Pregnancy and Risk of Subsequent PreeclampsiaDocument7 paginiDietary Fiber Intake in Early Pregnancy and Risk of Subsequent PreeclampsiamustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition and Stroke: Review ArticleDocument9 paginiNutrition and Stroke: Review Articlerichie_ciandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gastric Volvulus: Bang Chau, Susan DufelDocument2 paginiGastric Volvulus: Bang Chau, Susan DufelmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selected Health IndicatorsDocument93 paginiSelected Health IndicatorsmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vitamind - TB PDFDocument7 paginiVitamind - TB PDFmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- 24 4 385Document6 pagini24 4 385mustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parenteral Nutrition in Critical CareDocument5 paginiParenteral Nutrition in Critical CaremustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Logistics Execution Suite Manages Warehouse OperationsDocument9 paginiLogistics Execution Suite Manages Warehouse OperationsmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bushra, 2010Document7 paginiBushra, 2010Citta ArastiÎncă nu există evaluări

- ViaClinica RICA EnglishDocument127 paginiViaClinica RICA EnglishmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cooking RequirementsDocument1 paginăCooking RequirementsvectorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tingkat Pengetahuan Dan Praktik Penjamah Makanan Tentang Keamanan Pangan Pada Usaha Katering Di Kota MakassarDocument4 paginiTingkat Pengetahuan Dan Praktik Penjamah Makanan Tentang Keamanan Pangan Pada Usaha Katering Di Kota MakassarmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Posterior Sagittal Anorectoplasty in Anorectal MalformationsDocument5 paginiPosterior Sagittal Anorectoplasty in Anorectal MalformationsmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition Management - Sirosis PDFDocument10 paginiNutrition Management - Sirosis PDFmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition Management - Sirosis PDFDocument10 paginiNutrition Management - Sirosis PDFmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nousea and Vomiting Mediciation 130509Document3 paginiNousea and Vomiting Mediciation 130509mustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- BCAADocument8 paginiBCAAmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition Management - Sirosis PDFDocument10 paginiNutrition Management - Sirosis PDFmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hungx BuiDocument92 paginiHungx BuimustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ioi 160069Document9 paginiIoi 160069mustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Micronutrient and Sam - Am J Clin Nutr-2011-Lemaire-585-93Document9 paginiMicronutrient and Sam - Am J Clin Nutr-2011-Lemaire-585-93mustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laporan Week 9 BDocument36 paginiLaporan Week 9 BmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18 Total Quality ApstractDocument5 pagini18 Total Quality ApstractPooja GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oral Rehydration Solution:: Future ProspectDocument48 paginiOral Rehydration Solution:: Future ProspectmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mustika Arum - 115070300111038 - Application of Hurdles For Extending The Shelf Life of Fresh FruitsDocument18 paginiMustika Arum - 115070300111038 - Application of Hurdles For Extending The Shelf Life of Fresh FruitsmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metronidazole Baxter in FDocument14 paginiMetronidazole Baxter in FmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diarrhoea Guidelines PDFDocument58 paginiDiarrhoea Guidelines PDFmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metronidazole: Common Drug Name Common Brand NamesDocument1 paginăMetronidazole: Common Drug Name Common Brand NamesmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer Medicine Information Arrow - Ranitidine: What Is in This LeafletDocument8 paginiConsumer Medicine Information Arrow - Ranitidine: What Is in This LeafletmustikaarumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3Document4 paginiChapter 3JEWEL ANN ABUNALESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Objective: National Council For Teacher Education Act, 1993 (No. 73 of 1993)Document19 paginiObjective: National Council For Teacher Education Act, 1993 (No. 73 of 1993)naresh chandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdul Baki ZDocument251 paginiAbdul Baki ZQuadri AlayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Systematic Mapping Study of Software Development With GithubDocument20 paginiA Systematic Mapping Study of Software Development With GithubJaime SayagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laporan Sistematika HewanDocument10 paginiLaporan Sistematika HewanIntan KhoerunnisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research and Publication EthicsDocument4 paginiResearch and Publication EthicsHemalatha SivakumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Sales Promotor 2Document33 paginiEvaluation of The Effectiveness of Sales Promotor 2Cali AshuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tsur, Reuven - Poetic Conventions As Cognitive FossilsDocument305 paginiTsur, Reuven - Poetic Conventions As Cognitive FossilsDavid Andrés Villagrán RuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nelson - Literacy and Leadership Management Skills of Sustainable Product DesignersDocument11 paginiNelson - Literacy and Leadership Management Skills of Sustainable Product DesignersISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to Accounting TheoryDocument29 paginiIntroduction to Accounting TheoryMeivi UlfaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 【Book】Creativity In Context Update To The Social Psychology Of Creativity PDFDocument468 pagini【Book】Creativity In Context Update To The Social Psychology Of Creativity PDF余涛80% (5)

- Egypt Geography Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiEgypt Geography Lesson PlanWilliam BaileyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.7.4 The Illegalist SchoolDocument10 pagini1.7.4 The Illegalist SchoolJohn Bates BlanksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sri Devaraj Urs Medical CollegeDocument1 paginăSri Devaraj Urs Medical CollegeRakeshKumar1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Abm12 Group3 Pr2 FinalDocument23 paginiAbm12 Group3 Pr2 Finalmarkbencentespenida2Încă nu există evaluări

- BTSN Newsletter 2011Document7 paginiBTSN Newsletter 2011plan3t_t3chÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Doctor of Philosophy Barroga Roger 2019Document275 paginiThesis Doctor of Philosophy Barroga Roger 2019Esperedion AtilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Formation in Pre-Colonial Sub-Saha PDFDocument99 paginiState Formation in Pre-Colonial Sub-Saha PDFBewesenuÎncă nu există evaluări

- B.Tech. 1st To 8th CBCSDocument137 paginiB.Tech. 1st To 8th CBCSRohit PathaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mech Edu Us GermanyDocument5 paginiMech Edu Us GermanyHalley WanderbakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capstone Module 1 LITERATURE REVIEWDocument3 paginiCapstone Module 1 LITERATURE REVIEWJessica AngayenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hnrda 2022-2028Document193 paginiHnrda 2022-2028rainfialaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Media Literacy Perspective - BrownDocument14 paginiMedia Literacy Perspective - BrownDimas SetiawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal Philosophy of The Importance of Nursing EducatorsDocument4 paginiPersonal Philosophy of The Importance of Nursing Educatorsapi-338453738Încă nu există evaluări

- Emptiness of Emptiness PDFDocument291 paginiEmptiness of Emptiness PDFAndrei-Valentin Bacrău100% (2)

- Syllbus-of-B.A. - Hons - English PDFDocument301 paginiSyllbus-of-B.A. - Hons - English PDFRajiv Malhotra50% (2)

- Book of Yusuf Group PDFDocument32 paginiBook of Yusuf Group PDFmaka stationeryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Guide 3 - Mixed Methods Approach To ResearchDocument9 paginiStudy Guide 3 - Mixed Methods Approach To Researchtheresa balaticoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1-5Document89 paginiChapter 1-5Dannaj Jabola100% (1)

- Mahder GeletaDocument90 paginiMahder GeletaFanuel MarqosÎncă nu există evaluări