Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Charnock-2014-Lost in Space - Lefeb

Încărcat de

AndradeLuisTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Charnock-2014-Lost in Space - Lefeb

Încărcat de

AndradeLuisDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The South Atlantic Quarterly 113:2, Spring 2014

doi 10.1215/00382876-2643639 2014 Duke University Press

Greig Charnock

Lost in Space? Lefebvre, Harvey,

and the Spatiality of Negation

It is all ne and good . . . to evoke relational concep-

tions such as the proletariat in motion or the multitude

rising up. But no one knows what any of that means

until real bodies go into the absolute spaces of the

streets . . . at a particular moment in absolute time. . . .

. . . To neglect that connectivity is to court

political irrelevance.

David Harvey, Spaces of Neoliberalization

What, if anything, is intrinsically spatial about

saying no to austerity, or to capitalism generally?

It certainly appears that the urban character of

recent popular uprisingsfrom Tahrir Square to

Syntagma Square, from Puerta del Sol to Zuccotti

Parksuggests that there is some necessarily

spatial dimension to contemporary forms of revolt.

John Holloway suggests that interstitial revolution

can be usefully thought of in terms of cracks:

moments of refusal (of the no) that reveal the

possibility of a (not-yet-)existing world built on

dignity and mutual recognition rather than on

abstract labor and the command of money. Per-

haps the most obvious way of thinking of cracks

is in spatial terms, proposes Holloway (2010: 27):

Here . . . we shall not accept the rule of capital or

the state, we shall determine our own activity.

314 The South Atlantic Quarterly

Spring 2014

This article is motivated by Holloways part-spatial conceptualization

of cracks, but also out of an engagement with two avowedly dialectical and

Marxist thinkers of space whose works have found contemporary reso-

nance in the anti-austerity-related slogan of the right to the city: Henri

Lefebvre and David Harvey. In searching for initial clues to the connectiv-

ity between time, space, and negation, I nd that the two versions of the

production of space offered up by Lefebvre, on the one hand, and Harvey,

on the other, are not as easily reconcilable as one might be led to think.

Both thinkers open the door to markedly differentand, in their own way,

problematicnotions of the critique of capitalist space and of the spatiality

of emancipatory politics.

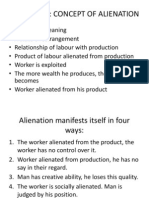

Lefebvre: Negative Critique and the Spatiality of (Dis-)Alienation

Prior to the discovery of the works of Lefebvre by Anglophone scholars in

the 1990s, his reception in France and elsewhere was primarily as someone

who wrote about dialectical method (Shields 1999: 109). A hallmark of Lefeb-

vres writings is therefore the extent to which they are consistently method-

ologically minded, the dialectic being the thread that runs through his pro-

lic and thematically varied output over several decades. This is certainly the

case with his writings on space, originally published between 1968 and

1974. In these, and in addition to arguing persuasively that space should be

thought of in dialectical terms of its social productionrather than in purely

Cartesian and Euclidean termsLefebvres signal methodological contribu-

tion is to highlight the antirepresentational orientation of Hegelian Marxism

(see Charnock and Ribera-Fumaz 2011). That is, his critique of formal logic

emphasized at once the dialectics ability to reconcile social scientic analy-

sis with ux, inner relations, determinate negation, mediation, and Becom-

ing, while also exposing the terrorism inherent to dominant, representa-

tional norms of analysis based on purely formal or speculative methods of

abstraction. For Lefebvre, representational knowledge about the world is but

an ideological product of the will to abstract from concrete, lived experience

(du vcu) (e.g., Lefebvre 1991: 230). Time and again, Lefebvre reveals the lim-

its to formal logic, but also at the level of serviceable representations that

have a real and violent effect. In his work on space and urbanism, Lefebvre

therefore railed against modelsabstract but concretely applicable repre-

sentations of a projected, planned society in which some kinds of social and

spatial practice are condoned and others dismissed as pathological or dys-

functional. Lefebvres work therefore reinforces that aspect of the dialectic

Charnock

Lefebvre, Harvey, and the Spatiality of Negation 315

which Karl Marx demonstrated in his own critique of political economy: that

it has the power to offer an understanding of the real movement of society

while also exposing even the most developed form of nondialectical con-

sciousness of that society to be ideology and necessarily in the service of the

reproduction of alienation.

Lefebvres antidote to formal logic, speculative philosophies, struc-

turalism, existentialism, and Soviet diamat (dialectical materialism) was

what he repeatedly calls metaphilosophy (see Charnock 2010). At root,

metaphilosophy is concerned with praxis: Production produces man. So-

called world history or the history of the world is nothing but the history

of man producing himself, of man producing both the human world and

the other man, the (alienated) man of otherness, and his self (his self-con-

sciousness) [sic] (Lefebvre 2008: 1:237). The purpose of critique, for Lefeb-

vre, is therefore to illuminate and decipher human alienation on the basis

of praxis (137); it is to ask: How can men live as they are living, and how

can they accept it? [sic] (30). Lefebvres own exploration of this question

led him to develop his critique of everyday life over the course of four

decades and to his work on the production of (urban) space.

Lefebvres gambit in his 196874 writings is his assertion that urban-

ization has superseded industrializationa historical process that he

claims Marx could not have foreseen, situated as he was within an epoch of

competitive capitalism (Lefebvre 1976: 10). Lefebvre explains that capital-

ism gave birth to urbanization as an active abstraction (Kerr 1994: 28), in a

sense, a wayward and patricidal offspring of industrialization (Lefebvre

2000: 47; Merrield 2011b: 474). Motivated by what he judged to be an insuf-

cient attention to space in Marx and Marxism generally (Elden 2004b: 184

86)as well as his own immersion in architectural and urbanist milieus

from the late 1960s (Stanek 2011)Lefebvre sought to show how capitalism

produces its own abstract spacematerially and in ideological, representa-

tional termsand, in so doing, creates the permissive conditions for the

reproduction of the relations of production according to their own imma-

nent requirements and not simply those that feed and support the produc-

tion of surplus value in the factories (Lefebvre 1976). Time has been

reduced to constraints of spacecircumscribed and suppressed within

the abstract space of the urban form. The process of mediation that repro-

duces the relations of production in a contradictory form, according to Lefeb-

vre, is therefore that of urbanizationthe production of (urban) space.

This, then, is what is new and paradoxical, explains Lefebvre (1976:

17): The dialectic is no longer attached to temporality. . . . To recognise space,

316 The South Atlantic Quarterly

Spring 2014

to recognise what takes place there and what it is used for, is to resume

the dialectic; analysis will reveal the contradictions of space. Praxis and pro-

duction are still at the root of Lefebvres analysis, and it should be stressed

that class struggle and bourgeois class strategy (directed through the homog-

enizing, terrorizing power of the state) still has a large part to play in his

depiction of the urban mode of existence as one of permanent crisis (Lefeb-

vre 2003; 2008: vol. 3). Lefebvre remains committed to tracing the move-

ment of (dis-)alienation and in putting to work the critical labor of the nega-

tive (Zuss 2005). According to Lefebvre, we should view space in

contradictory termsdifference being necessarily constitutive of urbaniza-

tion, notwithstanding its homogenizing drive to concretize abstract space.

Lefebvre (2000: 75) traces the existence of irreducibles, contradictions and

objections that intervene and hinder the closing of the circuit [of everyday

life], that split the structure. In his view, then, there is some residuum of

human subjectivity and style that capital has been unable to subsume, invert,

or control, and it is this insight that holds the key to understanding the con-

tradictions inherent to the production of abstract space.

Lefebvres now famous clarion call for the right to the city was, there-

fore, one that he bequeathed to urban subjects brought together under the

centralizing and homogenizing process of urbanization but subjected to a

programmed circuit of everyday life in, what he termed, the bureaucratic

society of controlled consumption (Lefebvre 2000). The working class

remains the revolutionary subject for Lefebvrenot exclusively because of

its exploitation as the source of labor-power or its relation to the development

of the productive forces in industry, but because it gathers the interests . . .

of the whole society and rstly of all those who inhabit (Lefebvre 1996: 158).

Ultimately, then, Lefebvres recourse to Martin Heidegger reveals the extent

to which the class struggle is now no longer necessarily a struggle against

capital; rather, the struggle is against the reduction of inhabiting (habiter,

wohnen) to habitat (Elden 2004a: 96) and against the production of space as

determined by anything other than generalized self-management (autoges-

tion) of all urban citizens on the basis of the mutual recognition of difference

and particularity.

Ultimately, for Lefebvre, an urban revolution remained only a

possibilityalbeit one that has been revealed in all too transient, explosive

moments such as that of the events of May 1968. Like Holloways cracks,

Lefebvres moments attest to the interstitial character of revolution and reso-

nate, perhaps, with Theodor Adornos methodological preoccupation with

opening the non-conceptual within the concept (Bonefeld 2012: 130). How-

Charnock

Lefebvre, Harvey, and the Spatiality of Negation 317

ever, unlike Werner Bonefeld and Holloway, who cling to time as the locus of

critique, Lefebvre suggests that the critical labor of the negative should nec-

essarily be aimed at space: (Social) space is a (social) product, asserts Lefeb-

vre (1991: 26), and there is a politics of space because space is political

(Lefebvre 2009: 174). As one critic corroborates, Lefebvre attempts to

develop a method which is able to apprehend social space as such, in its gen-

esis and its form, with its own specic time or times (the rhythm of daily

life), and its particular centres and, what Lefebvre calls, polycentrism (agora,

temple, stadium, etc.) (Kerr 1994: 25). This reading of Lefebvres identica-

tion of the social content of spatial forms as being the key to the possible,

and to the extent that he nds the Marxian critique of political economy to be

a once necessary but, now, insufcient and misdirected endeavor, has pro-

found implications for both critique and emancipatory politics.

The Limits to Lefebvre

There are several possible objections to Lefebvres arguments. One might

justifiably criticize Lefebvre for merely asserting, and never explicitly

explaining, the salience of the urban problematique (Harvey 1974: 239). One

might also raise concerns about the contextual boundedness of aspects of

Lefebvres work (Brenner 2008: 242), insofar as it is of its time (steeped in

frustration with everyday life in Gaullist France). Alternatively, Lefebvre has

been dismissed as but another outmoded Marxist whose social critique

has been rendered obsolete by the transformation to exible capitalism and

the transformation of the subaltern subjectivity of the liberated individ-

ual (Ronneberger 2008: 14041). But I want to highlight fundamental

issues with Lefebvres application of his dialectical logic to the urban and

to space from the perspective of the critique of political economy, to offer a

Marxian interrogation of Lefebvres Marxism, in other words.

The basis of an arraignment against Lefebvre is already suggested in

Neil Smiths (1990: 92, 189n46) passing reference to Lefebvres reproduc-

tionism and to his drawing of too marked a distinction between the devel-

opment of the forces of production and the social relations of production. But

this is more developed in a little-known article by Derek Kerr. In it, he sur-

mises of Lefebvre (1976, 1991) that class struggle and history are reduced to

abstract time and exist in the container of abstract space, while this space has

contradictions of its own which can then externally envelop historical con-

tradictions. But by separating out contradictions of space from those in space

and by reducing class struggle and history to the latter, it is not clear what

318 The South Atlantic Quarterly

Spring 2014

constitutes the contradictions of space (Kerr 1994: 32). He continues: If

social relations are inherently spatial and temporal then there can be no

separation in/of dualism (32); furthermore, to displace time by space

merely obscures the dynamic and contradictory nature of the capital rela-

tion and the ways in which this expresses itself in a spatially uneven way

through . . . the production of space in its own image (34).

1

Against Lefeb-

vre, Kerr argues:

Marx was not limiting his analysis to time, but to uncovering the contradic-

tory constitution of the capital relation (see Bonefeld 1993) as it attempts to

transform and express itself through the spatial and temporal modalities of

existence. It is the capital relation that continually attempts to subordinate the

whole (space) of society to the abstract logic of linear time, the ticking of the

factory clock. This abstract time is not the concrete history of capitalism, but

rather is the dominant and contradictory tendency through which that history

expresses itself, one which continually attempts to reduce the internally

related and qualitative nature of both space and time to the quantitative metric

of value. As such, the form, nature and very existence of capitalist space

expresses and adheres in and through the contradictory . . . presence of labour

in capital. This is the dialectic, not one of time nor of space but . . . a negative

dialectic, a dialectic of negation with no certain synthesis. . . . The history of

capitalism is, therefore, none other than the struggle over and through space

as capital attempts to transform the entire spatial existence of society into a

machine for the production and quantitative expansion of surplus value in

terms of the metric of socially necessary labour time. (32)

Ultimately, Kerr abandons Lefebvre. He is sentenced to . . . wander in

space (23).

2

Being lost in space takes its toll, judging from the ways Lefebvre is

inuencing theorizations of space and politics and in the context of recent

urban uprisings and occupations. For instance, Andy Merrield (2011a: 1)

who draws direct inspiration from Lefebvrehas proposed a new, magical

Marxism: a Marxism that no longer calls itself scientic and has given up

on the distinction between form and content, between appearance and

essence . . . a Marxism that opens up the horizons of the afrmative and

reaches out beyond the dour realism of critical negativity. The implication

of expurgating Marx in favor of a more enigmatic, more afrmative notion of

emancipatory politics is of critical importance. One danger is that anticapi-

talism becomes a matter of resistance for the sake of resistance: a posture

that demands no prior (anti-)ontological critique (Bonefeld 2012).

3

Charnock

Lefebvre, Harvey, and the Spatiality of Negation 319

Harvey: Capitalist Urbanization and the Spatiality of Class Struggle

The hallmark of Harveys extensive writings on crises in generaland the

current crisis, especiallyhas precisely been his recourse to substantive

social theorization and, almost exclusively, to Marx (e.g., Harvey 1982, 1985,

2010). Harveys analysis of the current crisis appears to validate what is per-

haps his own signal contribution since the early 1970s, namely, how urban-

ization has been crucial to the spatial organization of capitalist production

and reproduction, and how urban centers came to play a role as active

moments in the dynamics of overaccumulation-devaluation.

4

While we can assuredly acknowledge both Harveys and Lefebvres con-

tribution to thinking about space in dialectical terms, we can also begin to

distantiate themand notwithstanding Harveys recent tribute to Lefeb-

vres vision in Rebel Cities (2012). Even this book attests to Harveys own con-

sistency insofar as it continues to foreground the question of capitalist time

over capitalist space. Take this passage, published almost thirty years ago:

The circulation of capital makes time the fundamental dimension of human

affairs. Under capitalism, after all, it is socially necessary labor time that forms

the substance of value, surplus labor time that lies at the origin of prot, and

the ratio of surplus labor time to socially necessary turnover time that denes

the rate of prot and, ultimately, the average rate of interest. . . . Under capital-

ism, therefore, the meaning of space and the impulse to create new spatial

congurations of human affairs can be understood only in relation to such

temporal requirements. The phrase annihilation of space by time does not

mean that the spatial dimension becomes irrelevant. It poses, rather, the ques-

tion of how and by what means space can be used, organized, created, and

dominated to t the rather strict temporal requirements of the circulation of

capital. (Harvey 1985: 37)

Fast-forward to 2012 and Rebel Cities: Harvey discusses the common.

Against Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2009), he foregrounds the ques-

tion of the production and appropriation of wealth (a matter of time) over

that of the common (and its spatial counterpart, the enclosure): The real

problem lies with the private character of property rights and the power

these rights confer to appropriate not only the labor but also the collective

product of others. Put another way, the problem is not the common per se,

but the relations between those who produce and capture it at a variety of

scales and those who appropriate it for private gain (Harvey 2012: 7879).

He also proposes that the urban process be reconceptualized to allow for a

320 The South Atlantic Quarterly

Spring 2014

reinvigoration of the Marxian notion of class struggle and to point toward an

effective political strategy for the working class (broadly conceived): There is

a seamless connection between those who mine the iron ore that goes into

the steel that goes into the construction of the bridges across which the

trucks carrying commodities travel to their nal destinations of factories

and homes for consumption. All of these activities (including spatial move-

ment) are productive of value and of surplus value. . . . Organized, those

workers would have the power to strangle the metabolism of the city (Har-

vey 2012: 13031).

To summarize Harveys long-standing position: capital, impelled by

the coercive laws of competition, constructs its own spatial landscape con-

sisting of physical but also social infrastructures that are appropriate, for a

time at least, to its drive to accumulate relative surplus valueand with all

the implications that brings for the spatial organization of the international

division of labor, for uneven geographic development, and for crisis forma-

tion (Harvey 1982: chap. 12). In so doing, however, capital produces a terrain

in and through which all workers involved in the production and circulation

processwithin or together with urban social movements demanding the

right to the city or to urban commonscan organize and engage in struggle

to act as a barrier to the process of capital accumulation. At the heart of the

passage on class struggle from Rebel Cities, quoted above, is a logic of tempo-

ral disruption, of blockage, of using capitals metabolic dependence on pro-

duced social and physical infrastructures (as a means of meeting its own

immanent temporal requirements) against it. What emerges, therefore, is a

different conceptualization of the politics of space from that offered by Lefeb-

vre; oriented, as Harveys is, to the necessarily prior and temporal under-

standing of capital accumulation as the determinant of the production of

space, of urbanization, and of the periodic creative destruction of a land-

scape of physical and social infrastructures built in its own image (Harvey

1985: 162). It also, certainly, contradicts any suggestion that prior substantive

theorization be ditched by anticapitalist movements: Citizen and comrade

can march together in anti-capitalist struggle. . . . But this can occur only if

we become, as [urban sociologist Robert] Park long ago urged, more con-

scious of the nature of our task, which is collectively to build the socialist

city on the ruins of destructive capitalist urbanization (Harvey 2012: 153).

On Critical Thought and the Enigma of Class Struggle

It appears, then, that Harveys work might be considered as a relational and

spatially conscious corrective to Lefebvres reproductionism. Indeed, Har-

Charnock

Lefebvre, Harvey, and the Spatiality of Negation 321

veys recent writings appear to chime with Kerrs (1994: 34) verdict that

space will be an instrument in the struggle for change, but will certainly

not be the goal of that struggle, as Lefebvre suggests. But the possibility of

a synthesis between Harveys theorization of the production of space in capi-

tals own image and of negative dialecticsas championed by Holloway, for

examplerequires that potentially obstructive issues be addressed rst.

Holloways argument in Crack Capitalism develops his long-standing

championing of an antidogmatic open Marxism and of negative dialectics

as the proper basis of immanent critique. Elsewhere, he writes: Dialectics

means thinking the world from that which does not t, from those who do

not t, those who are negated and suppressed, those whose insubordination

and rebelliousness break the bounds of identity, from us who exist in-and-

against-and-beyond capital (Holloway 2009: 15). Bonefeld similarly empha-

sizes that negative dialectics are a necessary means of illuminating the

determinate movement of negativity and of engaging in critique. He writes,

However much the objective world has autonomized itself from acting indi-

viduals, it remains a form of human practice (Bonefeld 2012: 129). It fol-

lows, therefore, that critical theory rejects as total ideology the idea of resis-

tance for the sake of resistance. It demands a recognition of social contents

(Bonefeld 2012: 132).

In Noel Castrees (2006: 259) interpretation, most of Harveys work

until the late 1980s did reect such a mode of immanent critique insofar

as it seems to be a rather austere dissection of capitalisms temporalities

and spatialities, [and] it is also a non-moralistic indictment of this mode of

production; it shows that system to be crisis-prone and self-negatory (259).

But in subsequent writings, in Castrees opinion, Harveyconfronting a

crisis of Marxism within and outside academiaopted for criticism

(the resort to extraneous values and normative judgments) as a useful sec-

ond best to critique (260). Of course, in negative dialectics the very notion

that it is possible to judge an object (capitalism) from a vantage point that

stands outside it, and therefore outside of the very conceptuality of the object

itselfas is implied in Castrees distinctionis a fallacy (Bonefeld 2009).

But this does then beg the question of the extent to which Castree is able to

make such an allegation because Harvey himself conceives of critical thought

in realist epistemological termsthat is, whether Harveys project to expose

the objective irrationality of capitalism presupposes the separation of sub-

ject and object, which negative dialectics denounces. As Castree (2006:

264) does suggest, That most talismanic of Marxist ideasan insurgent

working-class actor who is capitalisms gravediggerhas been steadily

attenuated in Harveys work as the years have gone by. . . . Ironically, his is

322 The South Atlantic Quarterly

Spring 2014

a critical theory that lacks a subject. Is Harveys call for a broader conceptu-

alization of class struggle, in Rebel Cities, for example, in some way symp-

tomatic of a subject-object dualism? And, in trying to make his earlier cri-

tique more relevant (Castree 2007), has Harvey fallen prey to the view that

social theory requires validation by means of empirical corroboration (Cal-

linicos 2005: 58), [which] debases the critical purpose of thought (Bonefeld

2012: 128)?

Kerr (1996) appears to corroborate such a view, and he questions even

Harveys works that Castree suggests do fulll the role of critique. In Har-

veys keystone The Limits to Capital (1982), Kerr identies two fundamental

and related dualisms: between the twin themes of accumulation and class

struggle and between theory and history. For Kerr, these compromise the

status of Harveys theory as critique since they exhibit how he constructs

theory rst, to unfold the law-like character of capital accumulation (complete

with its production of space), only then to switch his vantage point to that of

the working class and the history of its struggle over the urban process. Hence

it is not clear what constitutes that class struggle nor where it has come

from in order to be able to enter into and ght against the effects of these

laws. Furthermore, if a focus on struggle leaves theory behind, how is it pos-

sible to understand that struggle? (Kerr 1996: 70). From the point of view

of negative dialectics, the laws of accumulation are nothing else than the

movement of the class struggle. There is no separation of accumulation and

struggle, of concept and history (70).

Conclusions

Holloways reference to spatiality, mentioned in the introduction, perhaps

hints at the casual manner in which spacean extraordinarily complex

and elusive conceptfeatures in much social theory and commentaries on

contemporary urban uprisings, occupations of public squares, and so on.

In attempting to ground an understanding of what might be intrinsically

spatial about saying no to capital and to austerity, I have shown how a ver-

sion of dialectical negativity informs the work of Lefebvre, and his work on

space in particular. However, in conceiving of the dialectic as a general

method . . . applied by [Marx] to only a limited number of elds (Shields 1999:

109; emphasis added), Lefebvre saw t to formulate a method for the analysis

of space in itself and with temporalities of its own, autonomized from the

sociotemporal determinations of the production of value. Despite grasping

Charnock

Lefebvre, Harvey, and the Spatiality of Negation 323

the critical labor of the negative, albeit as a point of principle, this move

on Lefeb vres part puts him at odds with Bonefelds and Holloways open

Marxism:

5

If the social is inherently spatial and can only exist as such,

then the former cannot be juxtaposed to the latter; social contradictions do

not exist in space but express themselves spatially (Kerr 1994: 33). Critique

requires, instead, thought that foregrounds the question of abstract time and

only then asks after the determinations at play in the production of space in

capitals own image. Harvey has arguably achieved more in this regard than

any other theorist. If he is right to warn against neglecting the spatiality of

movement and at the risk of courting political irrelevance, perhaps, at the

very least, exponents of negative dialectics will have to be more explicit

about the spatiality of interstitial revolution and of communization. How-

ever, any attempt to synthesize Harveys analysis of the laws of motion of

capitalcomplete with his theorization of the urban process and of space as

an active moment in the dynamics of crisis formationwith a negative,

interstitial notion of anticapitalist revolution must rst have to reassure oth-

ers, and perhaps Harvey included, of the importance of negative dialectics

and of the need to resist the separation of structure and struggleprecisely

because the stakes are high.

Notes

With thanks to Tom Houseman, Alex Loftus, Tom Purcell, Ramon Ribera-Fumaz, Miguel

Robles-Durn, and Japhy Wilson for their criticism of an earlier version.

1 Kerr is paraphrasing Smith (1990: xv).

2 Lefebvre did focus largely on questions of time in his late works (see Lefebvre 1992).

3 Though not explicitly inuenced by Lefebvre, Erik Swyngedouw (2011), for example,

suggests that recent urban anti-austerity movements precisely represent an afrmation:

one of the equality of each and every one qua speaking beingsa condition that is

predicated upon afrming difference and the dissensual foundation of politics. For

Swyngedouw, then, interruptions that properly politicize public space require no prior

grounding in social theory, no recognition of social content la Bonefeld. In enacting

politics under the aegis of equalitythus interrupting the normalized order of, what

Jacques Rancire has termed, the Policesuch protest constitutes a proper political

sequence; one that can be thought and practiced irrespective of any substantive social

theorization (Swyngedouw 2011).

4 Much of my own work . . . has been about trying to track exactly such a process, to

understand how capital builds a geographical landscape in its own image at a certain

point in time only to have to destroy it later in order to accommodate its own dynamic

of endless capital accumulation, strong technological change, and erce forms of

class struggle (Harvey 2000: 177).

5 A crucial point missed by Charnock 2010.

324 The South Atlantic Quarterly

Spring 2014

References

Bonefeld, Werner. 1993. The Recomposition of the British State during the 1980s. Aldershot,

UK: Darmouth.

Bonefeld, Werner. 2009. Emancipatory Praxis and Conceptuality in Adorno. In Negativity

and Revolution: Adorno and Political Activism, edited by John Holloway, Fernando

Matamoros, and Sergio Tischler, 12247. London: Pluto.

Bonefeld, Werner. 2012. Negative Dialectics in Miserable Times: Notes on Adorno and

Social Praxis. Journal of Classical Sociology 12, no. 1: 12234.

Brenner, Neil. 2008. Henri Lefebvres Critique of State Productivism. In Space, Difference,

Everyday Life: Reading Henri Lefebvre, edited by Kanishka Goonewardena et al., 231

49. London: Routledge.

Callinicos, Alex. 2005. Against the New Dialectic. Historical Materialism 13, no. 2: 4160.

Castree, Noel. 2006. The Detour of Critical Theory. In David Harvey: A Critical Reader,

edited by Noel Castree and Derek Gregory, 24769. Oxford: Blackwell.

Castree, Noel. 2007. David Harvey: Marxism, Capitalism, and the Geographical Imagina-

tion. New Political Economy 12, no. 1: 97115.

Charnock, Greig. 2010. Challenging New State Spatialities: The Open Marxism of Henri

Lefebvre. Antipode 42, no. 5: 1279303.

Charnock, Greig, and Ramon Ribera-Fumaz. 2011. A New Space for Knowledge and People?

Henri Lefebvre, Representations of Space, and the Production of 22@Barcelona.

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29, no. 3: 61332.

Elden, Stuart. 2004a. Between Marx and Heidegger: Politics, Philosophy, and Lefebvres

The Production of Space. Antipode 36, no. 1: 86105.

Elden, Stuart. 2004b. Understanding Henri Lefebvre: Theory and the Possible. London:

Continuum.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2009. Commonwealth. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press

of Harvard University Press.

Harvey, David. 1974. Class-Monopoly Rent, Finance Capital, and the Urban Revolution.

Regional Studies 8, nos. 34: 23935.

Harvey, David. 1982. The Limits to Capital. Oxford: Blackwell.

Harvey, David. 1985. The Urbanization of Capital: Studies in the History and Theory of Capital-

ist Urbanization. Oxford: Blackwell.

Harvey, David. 2000. Spaces of Hope. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Harvey, David. 2006. Space as a Keyword. In Castree and Gregory, David Harvey, 27093.

Harvey, David. 2010. The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism. London: Prole

Books.

Harvey, David. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London:

Verso.

Holloway, John. 2009. Why Adorno? In Holloway, Matamoros, and Tischler, Negativity

and Revolution, 1217.

Holloway, John. 2010. Crack Capitalism. London: Pluto.

Kerr, Derek. 1994. The Time of Trial by Space? Critical Reections on Henri Lefebvres

Epoch of Space. Common Sense, no. 15: 1835. commonsensejournal.org.uk/les/2010

/08/CommonSense15.pdf.

Kerr, Derek. 1996. The Theory of Rent: From Crossroads to the Magic Roundabout. Capi-

tal and Class 20, no. 1: 5988.

Charnock

Lefebvre, Harvey, and the Spatiality of Negation 325

Lefebvre, Henri. 1976. The Survival of Capitalism: Reproduction of the Relations of Production.

Translated by Frank Bryant. London: Allison and Busby.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith.

Oxford: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1992. lments de rythmanalyse (Elements of Rhythmanalysis). Paris:

Syllepse.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1996. Writings on Cities. Edited and translated by Eleonore Kofman and

Elizabeth Lebas. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2000. Everyday Life in the Modern World. Translated by Sacha Rabinovitch.

London: Athlone.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2003. The Urban Revolution. Translated by Robert Bononno. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2008. Critique of Everyday Life. 3 vols. Translated by John Moore and Greg-

ory Elliott. London: Verso.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2009. Reections on the Politics of Space. In State, Space, World: Selected

Essays, edited by Neil Brenner and Stuart Elden, 16784. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Merrield, Andy. 2011a. Magical Marxism: Subversive Politics and the Imagination. London:

Pluto.

Merrield, Andy. 2011b. The Right to the City and Beyond: Notes on a Lefebvrian Re-

conceptualization. City 15, nos. 34: 47381.

Ronneberger, Klaus. 2008. Henri Lefebvre and Urban Everyday Life: In Search of the Pos-

sible. In Goonewardena et al., Space, Difference, Everyday Life, 13446.

Shields, Rob. 1999. Lefebvre, Love and Struggle: Spatial Dialectics. London: Routledge.

Smith, Neil. 1990. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. 2nd ed.

Oxford: Blackwell.

Stanek, ukasz. 2011. Henri Lefebvre on Space: Architecture, Urban Research, and the Produc-

tion of Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Swyngedouw, Erik. 2011. Every Revolution Has Its Square. Cities@Manchester (blog),

March 18. citiesmcr.wordpress.com/2011/03.

Zuss, Mark. 2005. A Blinking Sphinx: Theoretical Curiosity in Postwar Marxism. Situations:

Project of the Radical Imagination 1, no. 1: 4773.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban RevolutionDe la EverandRebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban RevolutionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (16)

- The Beat of The City: Lefebvre and Rhythmanalysis: Ryan MooreDocument17 paginiThe Beat of The City: Lefebvre and Rhythmanalysis: Ryan MooregagoalberlinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Empire Writes Back, Colonialism and PostcolonialismDocument4 paginiThe Empire Writes Back, Colonialism and PostcolonialismSaša Perović100% (1)

- Spatiality of Social Life: A Model of Spatial ComplexesDocument18 paginiSpatiality of Social Life: A Model of Spatial ComplexesVinicius MorendeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henry Lefebvre - Production of SpaceDocument6 paginiHenry Lefebvre - Production of SpaceStefan Kohlwes100% (1)

- Public International LawDocument64 paginiPublic International LawAngel Eilise0% (1)

- 1 Introduction - Domicile & Residence1Document7 pagini1 Introduction - Domicile & Residence1Anne VallaritÎncă nu există evaluări

- Douglas Greenberg, Stanley N. Katz, Steven C. Wheatley, Melanie Beth Oliviero - Constitutionalism and Democracy - Transitions in The Contemporary World-Oxford University Press (1993) PDFDocument416 paginiDouglas Greenberg, Stanley N. Katz, Steven C. Wheatley, Melanie Beth Oliviero - Constitutionalism and Democracy - Transitions in The Contemporary World-Oxford University Press (1993) PDFqaziammar4Încă nu există evaluări

- Kurt London - The Soviet Impact On World Politics (1974) PDFDocument328 paginiKurt London - The Soviet Impact On World Politics (1974) PDFWladimir SousaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 51 Phil JPub Admin 33Document19 pagini51 Phil JPub Admin 33Jeff Cruz GregorioÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Critique of Henri Lefebvre's Spatial Theories in His Production of SpaceDocument13 paginiA Critique of Henri Lefebvre's Spatial Theories in His Production of Spaceandywallis100% (1)

- Masters of Development Management Course on Public PolicyDocument56 paginiMasters of Development Management Course on Public PolicyMelikte100% (1)

- Kurian, George - The - Encyclopedia - of - Political - Science - Set PDFDocument1.942 paginiKurian, George - The - Encyclopedia - of - Political - Science - Set PDFRafaela Sturza100% (1)

- There Is A Politics of Space PDFDocument18 paginiThere Is A Politics of Space PDFJaume Santos DiazdelRioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pol Gov ReviewerDocument4 paginiPol Gov ReviewerkrizzellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- THE PRODUCTION OF SOCIAL SPACEDocument23 paginiTHE PRODUCTION OF SOCIAL SPACESelina Abigail100% (2)

- Nancy L. Rosenblum-Liberalism and The Moral Life-Harvard University Press (1989) PDFDocument310 paginiNancy L. Rosenblum-Liberalism and The Moral Life-Harvard University Press (1989) PDFAntonio Muñoz100% (2)

- UntitledDocument414 paginiUntitledkhizar ahmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michel de CerteauDocument7 paginiMichel de Certeauricpevanai0% (1)

- Martha Rosler: Culture Class: Art, Creativity, UrbanismDocument51 paginiMartha Rosler: Culture Class: Art, Creativity, UrbanismMQÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henri Lefebre's The Production of SpaceDocument8 paginiHenri Lefebre's The Production of SpaceKinkin Aprilia KiranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leibniz and MarxDocument7 paginiLeibniz and Marxstewe wondererÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origins of the Cold War SymposiumDocument26 paginiOrigins of the Cold War SymposiumaskjfashaskhfaskÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radical Chic? Yes We Are!Document16 paginiRadical Chic? Yes We Are!dekknÎncă nu există evaluări

- PUBLIC OPINION, PROPAGANDA AND BUREAUCRACYDocument29 paginiPUBLIC OPINION, PROPAGANDA AND BUREAUCRACYEzekiel T. Mostiero100% (2)

- Henri Lefebvre's The Production of SpaceDocument17 paginiHenri Lefebvre's The Production of SpaceaysenurozyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henri Lefebvre's Theories of Social SpaceDocument7 paginiHenri Lefebvre's Theories of Social SpacericpevanaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- (2010) Revisiting Lefebvre Final DraftDocument24 pagini(2010) Revisiting Lefebvre Final DraftStephen ReadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soja Socio Spatial DialecticsDocument20 paginiSoja Socio Spatial DialecticsCorinaIulia23Încă nu există evaluări

- SummaryDocument26 paginiSummarypriteegandhanaik_377Încă nu există evaluări

- Saving The White Building StorytellingDocument29 paginiSaving The White Building StorytellingOeung KimhongÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2011 A Renewed Right To Urban Life: A Twenty-First Century Engagement With Lefebvre's Initial "Cry" - Pugalis and GiddingsDocument24 pagini2011 A Renewed Right To Urban Life: A Twenty-First Century Engagement With Lefebvre's Initial "Cry" - Pugalis and Giddingsgknl2Încă nu există evaluări

- Henri Lefebvre's Theory of the Right to the CityDocument23 paginiHenri Lefebvre's Theory of the Right to the CityDjana_DzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stanek, Architecture As Space, AgainDocument6 paginiStanek, Architecture As Space, AgainLaiyee YeowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Make the Heterotopia: Gezi Park Occupy MovementDocument24 paginiMake the Heterotopia: Gezi Park Occupy MovementMeriç DemirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henri Lefebvre PDFDocument7 paginiHenri Lefebvre PDFMarios DarvirasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modernismus Last Post: Stephen SlemonDocument15 paginiModernismus Last Post: Stephen SlemonCamila BatistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LeFeA Waste of Space? Towards A Critique of The Social Production of SpaceDocument4 paginiLeFeA Waste of Space? Towards A Critique of The Social Production of SpaceIsabella Del GrandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review: The Postmodern Condition by David HarveyDocument7 paginiReview: The Postmodern Condition by David HarveyJaime PuenteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ordonnance, Discipline, Regulation Some Reflections On Urbanism, P. 2003. Ordonnance, Discipline, Regulation Some Reflections On UrbanismDocument11 paginiOrdonnance, Discipline, Regulation Some Reflections On Urbanism, P. 2003. Ordonnance, Discipline, Regulation Some Reflections On UrbanismLuis Berneth Peña0% (1)

- The Incredible Shrinking World? Technology and The Production of SpaceDocument27 paginiThe Incredible Shrinking World? Technology and The Production of SpaceJavier ZoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wiedmann SalamaChapter FinaldraftDocument19 paginiWiedmann SalamaChapter FinaldraftEunice KhainzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 00capítulo - The Routledge Handbook of Henri Lefebvre, The City and Urban SocietyDocument12 pagini00capítulo - The Routledge Handbook of Henri Lefebvre, The City and Urban SocietyJeronimoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Triangulating Utopia: Benjamin, Lefebvre, TafuriDocument13 paginiTriangulating Utopia: Benjamin, Lefebvre, TafuriEell eeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- LefebvreDocument52 paginiLefebvreDinaSeptiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boy ADocument5 paginiBoy AalexhwangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mape de Idei AshcroftDocument6 paginiMape de Idei AshcroftMadalina CeciuleacÎncă nu există evaluări

- SemioticsDocument66 paginiSemioticsilookieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fiche de Lecture Anthropologie Talya DeryaDocument6 paginiFiche de Lecture Anthropologie Talya DeryatalyaderyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry Into The Origins of Cultural ChangeDocument6 paginiThe Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry Into The Origins of Cultural ChangemocorohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sven Olov Wallenstein FoucaultDocument23 paginiSven Olov Wallenstein FoucaultArturo Aguirre Salas100% (1)

- Heterotopia and The CityDocument3 paginiHeterotopia and The CityWagner de Souza Rezende100% (1)

- Which Right To Which CityDocument19 paginiWhich Right To Which CitydoscristosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To AnarchismDocument7 paginiIntroduction To AnarchismAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comments On David Harvey's "The Condition of Postmodernity"Document6 paginiComments On David Harvey's "The Condition of Postmodernity"Night Owl100% (1)

- Manuel Delgado's Urban AnthropologyDocument19 paginiManuel Delgado's Urban AnthropologyAna Fontainhas Machado100% (1)

- The Dialectical SomersaultDocument12 paginiThe Dialectical SomersaultHeatherDelancettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards a Metaphilosophy of the UrbanDocument6 paginiTowards a Metaphilosophy of the UrbanBensonSraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction, The Spatial Turn in Social TheoryDocument6 paginiIntroduction, The Spatial Turn in Social TheoryZackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recension For Interpretation Lucien O.Document15 paginiRecension For Interpretation Lucien O.Lucien OulahbibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blum&Nast Lefebvre&LacanDocument22 paginiBlum&Nast Lefebvre&LacanReidÎncă nu există evaluări

- David Harvey DissertationDocument5 paginiDavid Harvey DissertationPayForSomeoneToWriteYourPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Shields Foucault's DandyDocument10 paginiShields Foucault's DandyconejinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Papers - 5 - 2triangulating Utopia: Benjamin, Lefebvre, Tafuri2754Document13 paginiPapers - 5 - 2triangulating Utopia: Benjamin, Lefebvre, Tafuri2754Erfan KhallaghiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articulation Theory A Discursive GroundDocument16 paginiArticulation Theory A Discursive GroundJosé LatabánÎncă nu există evaluări

- Desafio À História No Pós-GuerraDocument19 paginiDesafio À História No Pós-GuerraNaná DamasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Image, Space, Revolution: The Arts of Occupationauthor (S) : W. J. T. Mitchell Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Autumn 2012), Pp. 8-32 Published By: The University of Chicago PressDocument26 paginiImage, Space, Revolution: The Arts of Occupationauthor (S) : W. J. T. Mitchell Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Autumn 2012), Pp. 8-32 Published By: The University of Chicago PressDiky Palmana von FrancescoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Body As ReferentDocument6 paginiThe Body As ReferentvaleriapandolfiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postmodernism: A Movement Away From ModernismDocument9 paginiPostmodernism: A Movement Away From ModernismGerald DicenÎncă nu există evaluări

- WOLF - Rethinking The Radical WestDocument12 paginiWOLF - Rethinking The Radical WestCarolina Suriz100% (1)

- Mills - White Time PDFDocument16 paginiMills - White Time PDFCedric ZhouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morpheus A Brief History of Popular Assemblies and Worker CouncilsDocument10 paginiMorpheus A Brief History of Popular Assemblies and Worker CouncilsQuinchenzzo DelmoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- R3 - 1 Popular SovereigntyDocument7 paginiR3 - 1 Popular SovereigntyMattias GessesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- YDocument2 paginiYshahin67% (3)

- Quito Agenda FinalDocument7 paginiQuito Agenda FinalMartin TanakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- KARL MARX - AlienationDocument3 paginiKARL MARX - AlienationRishabh Singh100% (1)

- Weak States and WarDocument2 paginiWeak States and WarDaniela R. EduardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prelims Reviewer PPG Module 1 5Document20 paginiPrelims Reviewer PPG Module 1 5Jayson FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- CVDocument5 paginiCVroyce_koop8685Încă nu există evaluări

- Amalendu Guha - The Indian National Question - A Conceptual FrameDocument12 paginiAmalendu Guha - The Indian National Question - A Conceptual FrameEl BiswajitÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Top in Civil Service Exam - Upsc Gyan PDFDocument9 paginiHow To Top in Civil Service Exam - Upsc Gyan PDFR K MeenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandino and Other Superheroes The Function of Comic Books in Revolutionary NicaraguaDocument41 paginiSandino and Other Superheroes The Function of Comic Books in Revolutionary NicaraguaElefante MagicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Methods & LegalDocument50 paginiResearch Methods & LegalIshwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Citizen-Voter Education Module2Document8 paginiCitizen-Voter Education Module2teruel joyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas - What Was The New DealDocument6 paginiThomas - What Was The New DealSamson FungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Only PYQs - Political PartiesDocument22 paginiOnly PYQs - Political PartiesAishwaryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Review of Karl Marx's Revolutionary IdeasDocument6 paginiCritical Review of Karl Marx's Revolutionary IdeasUmairÎncă nu există evaluări

- QUIJANO 1989 Paradoxes of Modernity in Latin AmericaDocument32 paginiQUIJANO 1989 Paradoxes of Modernity in Latin AmericaLucas Castiglioni100% (1)

- White Minimalist Business Article Page Magazine CoverDocument1 paginăWhite Minimalist Business Article Page Magazine CoverAaravÎncă nu există evaluări