Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Rens Et Al A Multi-Party Negotiation Game For Improving Crisis Management Decision Making

Încărcat de

BoDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Rens Et Al A Multi-Party Negotiation Game For Improving Crisis Management Decision Making

Încărcat de

BoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Multi-Party Negotiation Game for Improving Crisis Management

Decision Making

Thomas Rens and Catholijn M. Jonker and M. Birna van Riemsdijk and Zhiyong Wang

EEMCS, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

t.p.rens@student.tudelft.nl

{c.m.jonker,m.b.vanriemsdijk,z.wang-1}@tudelft.nl

Abstract

This paper presents a training game intended to train crisis

management teams to negotiate collaboratively in order to

reach the group goal in the best way possible. The

importance of the group goal in comparison to their

individual goals is touched upon as well, as are various

conflicts that can occur during such a negotiation. The

game, which is implemented in the Blocks World 4 Teams

environment, gives a team a specific scenario and allows

them to negotiate a plan of action. This plan of action is

then performed by agents, after which the team members

will be debriefed on their performance. An experiment,

containing multiple rounds to test the effect the game has on

participants, is planned in the near future.

1. Introduction

A crisis can be defined as a threat to the basic

infrastructures or the fundamental values and norms of a

social system (Rosenthal 1984). Crises have the effects of

threatening higher priority goals and restricting response

times (Herman 1963). They also have a high level of

uncertainty (Rosenthal 1984).

Crises are usually managed using a network-centric

approach (van de Ven et al. 2008). This approach has

evolved from Network Centric Warfare (NCW) which was

used by the military (Alberts and Hayes 2007). The main

goal of NCW was to share information between all parties,

with the motivation being that having a superior

information position gives you an advantage over your

opponent. By adapting this to crisis management the

Network Centric Operations (NCO) system was conceived.

NCO allows information to be shared horizontally as well

as vertically throughout the organization dealing with the

crisis, and also allows information to be shared amongst

Copyright 2011, Association for the Advancement of Artificial

Intelligence (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

multiple units. The network-centric approach contains a

single commander in chief that controls all the actors in the

network. For this approach to work correctly all actors

should have the most up to date information, which means

that all information should be shared amongst all actors.

Also each of the actors should have common goals which

they all are striving to achieve.

However, a crisis management organization often

consists of multiple teams that contain multiple disciplines.

An evaluation of crises has shown that the previously

mentioned criteria for a working network-centric approach

are usually not met (van Santen, Jonker and Wijngaards

2009). These teams usually consist of members who do not

share the same goals, instead having their own goals that

they want to achieve.

Therefore (van Santen, Jonker and Wijngaards 2009)

claim that the crisis management decision making process

should be seen as a multi-party multi-issue negotiation, as

each of the parties in one of the decision-making teams has

their own interests and preferences. So in order to make a

decision each party has to make some compromises, the

final decision is based on the attitude, negotiation strategy

and negotiation skills of each party. Importantly, the

authors pose that the team will perform better if each team

member takes the preferences of other team members into

account. However at the start of the process each team

member will not have this knowledge, nor do they

typically try to gain this knowledge in the process. Thus

they negotiate competitively, meaning that they will

prioritize their own preferences. The authors thus propose

that crisis management workers should be trained so that

they can negotiate using a collaborative mindset instead of

a competitive mindset. In this paper we present the design

of a game to train precisely this.

Our game is played by a team that has one group goal to

achieve, with each team member also having his own goal

55

Robot-Human Teamwork in Dynamic Adverse Environment: Papers from the 2011 AAAI Fall Symposium (FS-11-05)

to achieve. A negotiation phase is used to create the plan of

action, after which software agents play the game based on

the negotiation outcome. This allows the players to see the

effect that their negotiation result has on the performance.

At the end of such a round a debriefing is given to

summarize the results to the team and let the team reflect

on their performance.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 will give

examples of other games that are similar to our game.

Section 3 details the overall design of the various parts of

our game, as well as the environment that we used to create

the game. Section 4 presents the protocol for the

experiment that we intend to perform in the near future

using our game. Section 5 is the conclusion of this paper.

2. Related Work

2.1 Negotiation

In a crisis management team decisions need to be made

about the proper course of action. However as a crisis

management team does not usually have a team leader,

instead consisting of various individuals with differing

roles with corresponding responsibilities and preferences,

this decision is not easily made. (van Santen, Jonker and

Wijngaards 2009)

For example in the case of a huge fire the police would

want to evacuate civilians from the area to keep them safe,

while the fire brigade does not want this as this would

create panic among the civilians located in the area.

Negotiation is one of the main procedures for dealing

with opposing preferences like these (Carnevale and Pruitt

1992). Such a negotiation can take several forms, either a

bilateral negotiation (between two parties only) or a multi-

party negotiation (between more than 2 parties) (Crump

2006). The topic of negotiation can usually be divided into

issues for which each issue has a set of possible values for

that issue. Each actor in the negotiation has a preferred

outcome, depending on their personal preferences, which

will most often not be shared by the other actor(s) as they

have differing interests.

The crisis management decision-making process can be

seen as a multi-party negotiation containing multiple issues

that are to be negotiated about (van Santen, Jonker and

Wijngaards 2009). The outcome of this negotiation

contains the plan of action for the crisis.

2.2 Related Games

Various other games (Agapiou 2006; Heuvelink 2009;

Moura 2003; Briot et al. 2009) have been created that

incorporate teamwork and/or negotiation to some extent. In

this section we will highlight the two that come closest to

our vision.

The SimParc project (Briot et al. 2009) focuses on

participatory park management. The goal of the game is to

make players understand conflicts and make them able to

negotiate about them. The game takes place in a park

council, which consists of various stakeholders like the

community or the tourism operator. The topic of discussion

is the zoning of the park which entails the desired level of

conservation for each part of the park. Each stakeholder

has a different preference concerning the zoning for each

part of the park, which quickly leads to conflicts of

interest. A special player type is the park manager who acts

as an arbiter and makes the final decision based on the

final input from the players. The game starts with an

allocation of roles to players after which they can present

their first proposal for each part of the park. After this the

players can freely negotiate about their proposals. This

negotiation is a multi-party negotiation as each player can

send messages through the system to multiple other

players. Bilateral negotiation is also possible when a player

negotiates only with a single other player. When all

negotiations are finished each player can adjust their

proposal if necessary and the park manager will then make

a final decision. Each player can then receive information

about their performance and can also ask the park manager

to explain his final decision.

The SimParc game is very similar to crisis management

as it contains a group goal (zoning the park), and each

stakeholder has his own goal to achieve. The players also

get the opportunity to negotiate with others in order to

come to a solution. However the game strongly differs

from crisis management in one aspect which is the

inclusion of a park manager who makes a final decision. In

crisis management teams such an entity does not exist as

teams do not have a hierarchical structure. In our game we

also do not intend to have a team leader, instead a team

where every team member has equal say.

A second example is Colored Trails. The game Colored

Trails (Moura 2003) was developed for testing the

decision-making procedures in task-oriented settings; it is

used for examining agent and human behavior. It focuses

on the interaction between the individual goal and the

group goal which is modeled in the game. The game can be

played by more than 2 players and consists of a rectangular

board containing colored squares. The players get a

starting position on this board, a goal position and an initial

set of chips. The objective for the players is to reach the

goal square. Players can only move to a square which is

adjacent to the one they currently occupy. This can only be

done however by having a chip with the same color as the

square the player wants to move to. This can result in a

negotiation between two players to exchange chips using a

standardized messaging protocol. Some parameters can be

changed to vary the game, for example the board visibility

can be changed so that players aren't allowed to see the

56

entire board or the knowledge of the other players' chips

can be toggled on or off. After the game is over, the results

are calculated using a scoring function which uses the

number of chips the player has left, the distance to the goal

position, the number of moves made by the player and

whether or not the player has reached the goal state. This is

the base scoring function of the game; it can be made more

complex by also taking into account the results of other

players with a certain weight. This weight can be adjusted

to make other players success more important than this

player's own success or vice versa. Group goals can thus be

modeled by adding a scoring component that can only be

maximized when all players reach their goal and are

therefore composed of multiple individual goals.

The Colored Trails game can therefore be adapted to

create a team having the group goal of maximizing other

players scores, while each team member also has an

individual goal of maximizing his own score. The

negotiation protocol in the game can then be used by the

team members to decide which chips to exchange with

what other team member. However this negotiation

protocol is currently limited to negotiations between two

players. A negotiation in the crisis management domain

often contains more than two players. In our game we

therefore also want the ability for multi-party negotiations

to be present. The Colored Trails game would therefore not

be suitable for our needs.

To conclude, SimParc uses a hierarchical structure for its

teams and Colored Trails does not support multi-party

negotiations. Therefore both games are not suitable for the

crisis management domain.

3. Game Design

3.1 Blocks World For Teams (BW4T)

For our game we use the Blocks World For Teams

(BW4T) environment as a basis (Johnson et al. 2009). This

environment was originally created to study human-agent

teamwork. We chose it because it is simple and it is not

directly related to crisis management. The latter is

important as we believe that crisis management

environments may not be realistic enough for our target

group of crisis management experts, which might hamper

their immersion in the game and reduce the training effect.

Therefore the environment was deliberately made more

abstract.

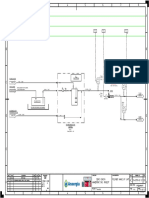

The BW4T environment, shown in Figure 1, consists of

9 rooms in which colored blocks are hidden. One or more

simulated robots, which can be controlled by humans or

software agents, can traverse these rooms in order to find

these blocks.

Figure 1. BW4T environment

The goal of the game is to collect certain colors in a

certain order. This color sequence is displayed to the right

of the green arrow. Players can pick up one block at a time

and can bring it back to a special room called the drop zone

where it should be dropped in accordance with the desired

color sequence. Players also have the ability to send

messages to other players, for example telling them what

blocks they have found in a room. A constraint that holds

for all players is that they can not see other players.

3.2 Extension of BW4T with Individual Goals

BW4T as proposed by Johnson et al. includes a group goal

(the color order in which blocks need to be collected). We

also need individual goals for the players, as we want to

create conflict between the group goal and individual goals

of players, and between the individual goals themselves.

We consider a conflict between two goals to exist when the

achievement of one goal hinders the achievement of the

other. Creating these conflicts is necessary as in crisis

management these conflicts also occur. Therefore we

extend the original BW4T game to include individual

goals. We will call this extension BW4T-I.

Various kinds of individual goals may be thought of,

creating different kinds of conflicts. Whether a conflict

with the group goal occurs, depends also on the choice of

the group goal. The criteria we propose for selection of

individual goals are as follows:

High severity of conflict, as a higher amount of

conflict should improve awareness of these

conflicts in players.

Possibility of an integrated plan, meaning the

possibility of creating a plan that achieves all

goals with a lower performance impact. This

should show players of our game that by

57

negotiating collaboratively these solutions can

be found.

Relation to crisis management, there should be

some way to translate a certain individual goal

to the crisis management domain. This would

allow us to use similar goals in the case of

creating a more realistic crisis management

training game in the future.

A combination of individual goals, group goal and block

configuration, is what we define as a scenario for the game.

Below we present two of the three scenarios that have been

implemented in our game, and that satisfy our criteria.

One scenario that has been implemented in our game is

the following:

Group goal: Red, Blue, Green, Yellow, Red,

Red, Blue, Green, Yellow

Individual goal (All team members): Search all

rooms

The block configuration for this scenario was chosen in

such a way that each room has to be explored in order to

achieve the group goal. The group goal therefore also

contains nine colors as there are nine rooms. This is not a

problem when only one player plays this scenario and

searches all the rooms. However with more players

searching all the rooms, this creates a conflict with the

group goal as it takes a lot longer to achieve it. An

integrated plan can be created to lessen the delay by letting

each player explore the rooms in a different order; however

the result will still be slower than dropping the individual

goals entirely. The amount of conflict is high as achieving

the group goal is delayed greatly by all players searching

every room. A translation to crisis management could be a

fireman needing to check all houses for survivors.

A second scenario that we have implemented is the

following:

Group goal: Red, Yellow, Purple, Blue, Blue,

Red

Individual goal (All team members): Collect

the most blocks relevant for the mission

In this scenario the only conflict that occurs is between

the team members individual goals. When one member

achieves his goal, the others cannot do this anymore. This

could result in a team that does not cooperate and splits up

into individual players. The conflict severity is therefore

very high. The choice of six colors in the group goal was

made deliberately to allow for an integrated plan of letting

each member collect two blocks and by doing that equally

distributing the loss amongst the team. However this all

depends on if the team members are prepared to agree with

this. The blocks configuration was chosen at random as it

has no further impact on this scenario. A translation to

crisis management could be a medic wanting to save most

of the victims because he feels responsible for doing this.

Other scenarios can be thought of, for example by giving

each team member different individual goals. A different

individual goal could be not entering a certain subset of

rooms (as these could be dangerous) or only being allowed

to pick up blocks of a specific color.

3.3 Game Outline

As our game is intended for training crisis management

experts, it will start with a negotiation phase. In this

negotiation phase the team members will need to make a

decision on how they are going to play the game,

depending on the group and individual goals. They need to

reach an outcome in ten minutes, which emulates the time

pressure contained in the crisis management decision

making process. This outcome will be given to the agents

that will play the game based on this. This allows the team

members to see the direct effect of their negotiation

outcome, and also prevents team members from changing

their plans during the game. After the agents finish the

game, a debriefing will be given to the team members. The

next round starts after this debriefing.

It was necessary to create a fixed negotiation domain for

the game, as the agents need to be able to work with the

negotiation outcome. In order to create this domain, we

conducted two experiments with the purpose of

determining the issues and values in this domain.

The first experiment was held with three participants

who were instructed to negotiate freely for three different

scenarios. The goal of this experiment was to obtain a list

of issues and values for the negotiation. For each scenario

each participant received the group goal and his individual

goal. The negotiations were filmed, from which we

gathered the following list of issues and values.

What information is shared between the team

members?

Values:

o Next location

o What blocks you've found in a room

o The blocks that are picked up

o The blocks that are dropped

What rooms in what order do the team

members explore?

Which team member collects what color from

the global goal list?

58

Do team members wait until all individual

goals have been reached before dropping the

last block?

Are team members allowed to enter other

rooms than the ones contained in their

exploration list?

Which team member drops their individual

goal?

Values: No-one, random or a specific team

member

A second experiment was then held with the goal of

finalizing this list. The set up of the experiment was similar

except that the participants were not allowed to negotiate

freely this time. Instead they were given the above list of

issues and values and were asked to discuss these issues if

they wanted, but they were also allowed to discuss issues

that were not contained in this list. These negotiations were

filmed and analyzed, after which it was determined that no

new issues or values had been discussed. Therefore this list

of issues and values is now used in the final game.

The debriefing phase summarizes the results of the

negotiation, including how the team members behaved

during the negotiation, as well as the resulting performance

of the agents. The team members will be told whether they

made any concessions when there were disagreements,

which indicates whether they have been cooperative. They

will also be told whether they made any concessions on

their individual goals in order to improve the performance

on the group goal. This performance is measured in the

game by taking the amount of time it took to complete it.

The performance itself will also be told to the team

members, as well as the difference between it and an

optimal solution for the group goal. This difference shows

them what effect their outcome actually had on the group

goals performance. This should lead them to reflect on

this outcome, and ideally change their perception on the

importance of the group and individual goals in a next

round.

3.4 Agents for BW4T-I

As the agents should show the effect of a certain

negotiation outcome all of their reasoning uses this

outcome.

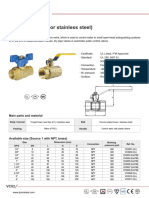

The agents follow a task structure containing three tasks.

These tasks are the exploration, delivery and drop off

tasks. These tasks will be explained briefly in this section.

Figure 2 shows the exploration task which is performed

first by an agent. This task is used to find the next block

that the agent should collect.

Figure 3 shows the delivery task which is used to pick

up the next color that the agent should pick up. The agent

will continue exploring if the next color that the agent

should pick up is not the next color in the group goal list.

Figure 2. Exploration task

Figure 3. Delivery task

Figure 4. Drop off task

Figure 4 shows the final task which entails dropping a

block in the drop zone. When this block is the last block,

meaning that the game will end after it is dropped, the

agent can decide to wait until all agents have reached their

individual goal or to finish his own goal if necessary.

i 3 li k

59

4. Experiment

Now that we have designed and implemented our game we

intend to test the effect it has on people. The goal of our

game is to shift the focus from individual goals to the

group goal as well as to show players what conflicts can

occur and to solve these conflicts more effectively. The

experiment will use three participants per group. Each

group will perform two rounds. There will be six groups in

total. Since three scenarios have been devised, this allows

us to test every scenario combination for their effects.

A subjective measurement will be done in the form of a

questionnaire which will measure the importance players

attach to the global and individual goals, as well as the

amount of conflict they noticed during the experiment and

how satisfied they are with the resolution of these. The

questionnaire will also contain reflection questions which

allow the participants to determine whether they were

satisfied with the outcome and if they would change their

behavior in retrospect.

Objective measurements will be done by analyzing the

negotiation as well as checking the agents performance. A

checklist of certain behaviors will be devised, which

should show a change in behavior from the first to the

second round in the experiment.

5. Conclusion

This paper presented a training game which can be used to

train crisis management experts in order to negotiate more

collaboratively. As the crisis management decision making

process can be seen as a multi-party multi-issue negotiation

where each party has their own goal in addition to a group

goal, all these elements are present in our game.

The BW4T environment was used as a starting point for

our game design. The environment already supported a

notion of a group goal in its scenarios. Individual goals

were added to new BW4T scenarios, in order to create

various conflicts, of which in total three were created.

Team members are allowed to negotiate the plan of

action for a scenario within 10 minutes, using a

predetermined negotiation domain.

Agents were implemented, that have the ability to play

the game based on the negotiation outcome. The

performance of these agents is used in the debriefing phase

in which the results of the previous scenario are relayed to

the team members. This should lead to a change in

behavior in the next round.

In the near future we intend to perform the experiment

that was described in the previous section, in order to test

whether our devised game actually changes the perception

towards individual and group goals in participants.

Moreover, we will investigate the use of automated

negotiation agents, using the Genius environment

(Hindriks et al. 2009), to replace part of the human

participants in the first phase of the game. These agents

should be endowed with the ability to exhibit different

negotiation styles, corresponding with more or less

collaborative behavior.

References

Rosenthal, U. 1984. Rampen, rellen, gijzelingen,

Crisisbesluitvorming in Nederland. Amsterdam/Dieren: De

Bataafsche Leeuw.

Herman, C. 1963. Some Consequences of Crisis Which Limit the

Viability of Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 8:

61-82.

van de Ven, J.; Essens, P.; Rijk, R. V.; and Frinking, E. Fiedrich,

F.; and de Walle, B. V. eds. 2008. Network Centric Operations in

Crisis Management. In Proceedings of the 5th International

Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and

Management, 764-774. Washington, DC.

Alberts, D. S.; and Hayes, R. E. 2007. Planning:Complex

Endeavors. Washington, DC.

van Santen, W.; Jonker, C.; and Wijngaards, N. 2009. Crisis

Decision Making Through a Shared Integrative Negotiation

Mental Model. International Journal of Emergency Management

6:342-355.

Crump, L. 2006. Multiparty negotiation: what is it? ADR Bulletin

8(7):1.

Carnevale, P. J.; and Pruitt, D. G. 1992. Negotiation and

Mediation. Annual Review of Psychology 43:531-582.

Agapiou A. 2006. An evaluation of a contract management

simulation game for architecture students. CEBE Transactions 3:

38-51.

Heuvelink A. 2009. Cognitive Models for Training Simulations.

Ph.D. diss., Faculteit der Exacte Wetenschappen, Vrije

Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Briot, J.-P.; Sordoni, A.; Vasconcelos, E.; de Azevedo Irving, M.;

Melo, G.; Sebba-Patto, V.; and Alvarez, I. 2009. Design of a

Decision Maker Agent for a Distributed Role Playing Game

Experience of the SimParc Project. Lecture Notes in Computer

Science 5920:119-134.

Moura, A. V. 2003. Cooperative Behavior Strategies in Colored

Trails. Bachelors Thesis. Department of Computer Science,

Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachussets.

Johnson, M.; Jonker, C.; Riemsdijk, B.; Feltovich, P. J.; and

Bradshaw, J. M. 2009. Joint Activity Testbed: Blocks World for

Teams (BW4T). In Proceedings of the 10th International

Workshop on Engineering Societies in the Agents World X.

Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Hindriks, K.; Jonker, C.M.; Kraus S.; Lin R.; and Tykhonov D.

2009. Genius: negotiation environment for heterogeneous agents.

In Proceedings of The 8

th

International Conference on

Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 1397-1398.

Richland, SC.: International Foundation for Autonomous Agents

and Multiagent Systems.

60

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Application of Game TheoryDocument8 paginiApplication of Game Theorybasanth babuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review Jun ParkDocument22 paginiLiterature Review Jun ParkJun ParkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Game Theory: Sri Sharada Institute of Indian Management - ResearchDocument20 paginiGame Theory: Sri Sharada Institute of Indian Management - ResearchPrakhar_87Încă nu există evaluări

- Personality, Emotion and Mood Simulation in Decision MakingDocument12 paginiPersonality, Emotion and Mood Simulation in Decision MakingToko Uchiha KaosunikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aquino Et Al - Juegos de Rol y SMADocument14 paginiAquino Et Al - Juegos de Rol y SMAMarcela Duque RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romi Kluweracademic2003Document14 paginiRomi Kluweracademic2003Aditya Galih DhamaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inve Mem 2014 217372Document12 paginiInve Mem 2014 217372Ana Maria GrecuÎncă nu există evaluări

- CONFLICT: Agents in Conflict Situation: Henrique Teles CamposDocument10 paginiCONFLICT: Agents in Conflict Situation: Henrique Teles CamposRafael RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Van Santen Crisis Decision Making Through A Shared Integrative Negotiation Mental ModelDocument14 paginiVan Santen Crisis Decision Making Through A Shared Integrative Negotiation Mental ModelBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discussion Forum Unit 5Document4 paginiDiscussion Forum Unit 5Motunrayo OliyideÎncă nu există evaluări

- Distributed Agent System Seminar Report: Arindam Sarkar (20081010)Document17 paginiDistributed Agent System Seminar Report: Arindam Sarkar (20081010)arwin10Încă nu există evaluări

- Game Theory PDFDocument57 paginiGame Theory PDFmanisha sonawane100% (1)

- 4.1 Game TheoryDocument73 pagini4.1 Game Theoryragul shreeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 28Document18 paginiPaper 28Trinh Huong Tra (K17 QN)Încă nu există evaluări

- Game Theory1Document5 paginiGame Theory1Mrunal PanchalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Game Theory in Solving Conflicts On Local Government Level: Croatian Operational Research Review CRORR 11 (2020), 81-94Document14 paginiGame Theory in Solving Conflicts On Local Government Level: Croatian Operational Research Review CRORR 11 (2020), 81-94TACN-2C-19ACN Nguyen Tien DucÎncă nu există evaluări

- WORKPLACE CONFLICT RESOLUTION - EditedDocument15 paginiWORKPLACE CONFLICT RESOLUTION - EditedHamza MayabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Masterstroke: the 48 most powerful negotiation tacticsDe la EverandMasterstroke: the 48 most powerful negotiation tacticsÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Negotiation Autor Learning Solutions AIM & Associés European InstitutionsDocument61 paginiWhat Is Negotiation Autor Learning Solutions AIM & Associés European InstitutionsJoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Components of Group Decision Support System (GDSS) .: 1. HardwareDocument9 paginiComponents of Group Decision Support System (GDSS) .: 1. HardwareRohit MahajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Application of Queuing TheoryDocument5 paginiThe Application of Queuing TheoryNikhil GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group Assignment Negotaitions r1 07.05Document15 paginiGroup Assignment Negotaitions r1 07.05Shweta SawaneeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Real-Time Proxy For Flexible Teamwork in Dynamic EnvironmentsDocument8 paginiA Real-Time Proxy For Flexible Teamwork in Dynamic EnvironmentsLuis AlvaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- A C I C A: Chieving Onsensus With Ndividual Entrality PproachDocument12 paginiA C I C A: Chieving Onsensus With Ndividual Entrality PproachPendar FazelÎncă nu există evaluări

- CONFLICT RESOLUTION Individual AssignmentDocument8 paginiCONFLICT RESOLUTION Individual AssignmentCaxton mwashitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ARMBRUSTER, Walter & BOGE, Werner - Efficient, Anonymous, and Neutral Group Decision ProceduresDocument18 paginiARMBRUSTER, Walter & BOGE, Werner - Efficient, Anonymous, and Neutral Group Decision ProceduresClóvis SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zihan Wang Conflict Management - Dispute Resolution EassyDocument4 paginiZihan Wang Conflict Management - Dispute Resolution EassyzihanÎncă nu există evaluări

- AssignmentDocument15 paginiAssignmentWahab MirzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Game Theory: Sri Sharada Institute of Indian Management - ResearchDocument20 paginiGame Theory: Sri Sharada Institute of Indian Management - ResearchPrakhar AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atdm Indivual AssignmentDocument26 paginiAtdm Indivual AssignmentJoshua JacksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy of Conflict Management Final Paper 001Document10 paginiPhilosophy of Conflict Management Final Paper 001Andreabg1100% (1)

- Artificial Intelligence and Online Dispute Resolution - LODDeR e ZELEZNIKOWDocument22 paginiArtificial Intelligence and Online Dispute Resolution - LODDeR e ZELEZNIKOWGiulia PradoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multi-Issue Negotiation PaperDocument14 paginiMulti-Issue Negotiation PaperJoao de Oliveira100% (13)

- Columbia University: Department of Economics Discussion Paper SeriesDocument26 paginiColumbia University: Department of Economics Discussion Paper Seriesnaoto_somaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discussion 5Document2 paginiDiscussion 5Neil ChandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daylamani-Zad2019 Article ChainOfCommandInAutonomousCoopDocument32 paginiDaylamani-Zad2019 Article ChainOfCommandInAutonomousCoopMuhamad Saladin AbdullohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Choose Your Role Instructional GuideDocument12 paginiChoose Your Role Instructional GuidehoulesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Game Theory Approach To The Analysis of Land and Property Development ProcessesDocument15 paginiA Game Theory Approach To The Analysis of Land and Property Development ProcessesHatim NathdwaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intelligent Negotiation Model For Ubiquitous Group Decision ScenariosDocument13 paginiIntelligent Negotiation Model For Ubiquitous Group Decision ScenariosLUZ KARIME TORRES LOZADAÎncă nu există evaluări

- BAM510 Unit Essay 4Document5 paginiBAM510 Unit Essay 4philipÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thinking Strategically (Review and Analysis of Dixit and Nalebuff's Book)De la EverandThinking Strategically (Review and Analysis of Dixit and Nalebuff's Book)Încă nu există evaluări

- Bilateral Bargaining With Externalities: Catherine C. de Fontenay and Joshua S. GansDocument51 paginiBilateral Bargaining With Externalities: Catherine C. de Fontenay and Joshua S. GansJoshua GansÎncă nu există evaluări

- Negotiation As An Interpersonal Skill Generalizability of Negotiation OutcomesDocument47 paginiNegotiation As An Interpersonal Skill Generalizability of Negotiation OutcomesÂngela FernandesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Select Negotiation StrategiesDocument12 paginiSelect Negotiation StrategiesnadiaadhamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swarm RL 34Document15 paginiSwarm RL 34MehreenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Use of Game Theory To Solve Conflicts in The Project Management and Construction IndustryDocument16 paginiThe Use of Game Theory To Solve Conflicts in The Project Management and Construction IndustryTridip KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application of Game Theory Approach in Solving Construction ConflictsDocument8 paginiApplication of Game Theory Approach in Solving Construction ConflictsnatanÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Approach To Visualize The Negotiation Preparation StepDocument8 paginiAn Approach To Visualize The Negotiation Preparation StepRaquel SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijcsis Final VersionDocument10 paginiIjcsis Final VersionSahar EbÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are The Methods of Conflict AnalysisDocument16 paginiWhat Are The Methods of Conflict Analysisleah100% (1)

- Multi-Party Negotiation SupportDocument22 paginiMulti-Party Negotiation SupportMelvinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 5 MBA Organizational Theory Behavior Written AssignmentDocument6 paginiWeek 5 MBA Organizational Theory Behavior Written AssignmentYared AdaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Village Activity: Conflict Consequences: Areas(s) of Peace EducationDocument6 paginiVillage Activity: Conflict Consequences: Areas(s) of Peace EducationLina María VacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Negotiation 1687882440Document61 paginiWhat Is Negotiation 1687882440MagodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Setting The Stage and Problem StatementDocument1 paginăSetting The Stage and Problem Statementabhijith namboodiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrative NegotiationDocument4 paginiIntegrative NegotiationyongshengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtual Team DynamicsDocument14 paginiVirtual Team DynamicsMUBASHIR MALIKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Game TheoryDocument28 paginiGame Theoryshreya5319100% (1)

- Application of Game Theory in Organisational Conflict Resolution: The Case of NegotiationDocument6 paginiApplication of Game Theory in Organisational Conflict Resolution: The Case of NegotiationMiguel MazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Stuart Mill's Theory of Bureaucracy Within Representative Government: Balancing Competence and ParticipationDocument11 paginiJohn Stuart Mill's Theory of Bureaucracy Within Representative Government: Balancing Competence and ParticipationBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Randy M. Shilts 1952-1994 Author(s) : William W. Darrow Source: The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1994), Pp. 248-249 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 02/09/2014 13:37Document3 paginiRandy M. Shilts 1952-1994 Author(s) : William W. Darrow Source: The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1994), Pp. 248-249 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 02/09/2014 13:37BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turner, B. (1976) - The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21 378-397Document21 paginiTurner, B. (1976) - The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21 378-397BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engert & Spencer IR at The Movies Teaching and Learning About International Politics Through Film Chapter4Document22 paginiEngert & Spencer IR at The Movies Teaching and Learning About International Politics Through Film Chapter4BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Info Pack 2014Document27 paginiInfo Pack 2014BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Airway Obstruction in Hunter Syndrome: Case ReportDocument6 paginiAcute Airway Obstruction in Hunter Syndrome: Case ReportBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- J Hist Med Allied Sci 2014 Kazanjian 351 82Document32 paginiJ Hist Med Allied Sci 2014 Kazanjian 351 82BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Update '89: Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, MD, Symposium DirectorDocument13 paginiUpdate '89: Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, MD, Symposium DirectorBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Patient Zero": The Absence of A Patient's View of The Early North American AIDS EpidemicDocument35 pagini"Patient Zero": The Absence of A Patient's View of The Early North American AIDS EpidemicBo100% (1)

- Wraith Et Al The MucopolysaccharidosesDocument9 paginiWraith Et Al The MucopolysaccharidosesBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muhlebach 2011. Respiratory Manifestations in MucopolysaccharidosesDocument6 paginiMuhlebach 2011. Respiratory Manifestations in MucopolysaccharidosesBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peters Et Al. 2003. Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Diseases - An Overview of Outcomes and Practice GuidelinesDocument11 paginiPeters Et Al. 2003. Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Diseases - An Overview of Outcomes and Practice GuidelinesBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tolun 2012 A Novel Fluorometric Enzyme Analysis Method For Hunter Syndrome Using Dried Blood SpotsDocument3 paginiTolun 2012 A Novel Fluorometric Enzyme Analysis Method For Hunter Syndrome Using Dried Blood SpotsBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stem-Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Disorders - HSCT - Inherited - Metabolic - Disorders 15082013Document19 paginiStem-Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Disorders - HSCT - Inherited - Metabolic - Disorders 15082013BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rheumatology 2011 Muenzer v4 v12Document9 paginiRheumatology 2011 Muenzer v4 v12BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Santos Et Al 2011. Hearing Loss and Airway Problems in Children With MucopolysaccharidosesDocument7 paginiSantos Et Al 2011. Hearing Loss and Airway Problems in Children With MucopolysaccharidosesBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Trials Update: Joseph Muenzer, M.D., PH.DDocument24 paginiClinical Trials Update: Joseph Muenzer, M.D., PH.DBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oussoren Et Al 2011. Bone, Joint and Tooth Development in Mucopolysaccharidoses - Relevance To Therapeutic OptionsDocument15 paginiOussoren Et Al 2011. Bone, Joint and Tooth Development in Mucopolysaccharidoses - Relevance To Therapeutic OptionsBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muenzer 2009 Multidisciplinary Management of Hunter SyndromeDocument14 paginiMuenzer 2009 Multidisciplinary Management of Hunter SyndromeBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muenzer Et Al. 2007. A Phase I-II Clinical Trial of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Mucopolysaccharidosis II Hunter SyndromeDocument9 paginiMuenzer Et Al. 2007. A Phase I-II Clinical Trial of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Mucopolysaccharidosis II Hunter SyndromeBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- McKinnis Bone Marrow Transplantation Hunter Syndrome The Journal of PediatricsDocument17 paginiMcKinnis Bone Marrow Transplantation Hunter Syndrome The Journal of PediatricsBoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Vitae - MICHAEL PDFDocument1 paginăCurriculum Vitae - MICHAEL PDFMichael Christian CamasuraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mohana Krishnan KsDocument2 paginiMohana Krishnan KsKanna MonishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bank of AmericaDocument3 paginiBank of AmericamortensenkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Odot Microstation TrainingDocument498 paginiOdot Microstation TrainingNARAYANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top 20 Web Services Interview Questions and Answers: Tell Me About Yourself?Document28 paginiTop 20 Web Services Interview Questions and Answers: Tell Me About Yourself?sonu kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iqmin A Jktinv0087205 Jktyulia 20230408071006Document1 paginăIqmin A Jktinv0087205 Jktyulia 20230408071006Rahayu UmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Initial PID - 19-0379 A01 01Document39 paginiInitial PID - 19-0379 A01 01rajap2737Încă nu există evaluări

- 2520 995 RevBDocument52 pagini2520 995 RevBgovindarulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Datasheet - HK f7313 39760Document7 paginiDatasheet - HK f7313 39760niko67Încă nu există evaluări

- The Combustion Characteristics of Residual Fuel Oil Blended With Fuel AdditivesDocument10 paginiThe Combustion Characteristics of Residual Fuel Oil Blended With Fuel AdditivesBunga ChanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huawei RTN 980-950 QoS ActivationDocument7 paginiHuawei RTN 980-950 QoS ActivationVenkatesh t.k100% (2)

- 49 CFR 195Document3 pagini49 CFR 195danigna77Încă nu există evaluări

- Daf RequestDocument1.692 paginiDaf Requestbrs00nÎncă nu există evaluări

- E DPT2020Document37 paginiE DPT2020arjuna naibahoÎncă nu există evaluări

- HS22186Document4 paginiHS22186daviÎncă nu există evaluări

- SP25Y English PDFDocument2 paginiSP25Y English PDFGarcia CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pakistan Machine Tool Factory Internship ReportDocument14 paginiPakistan Machine Tool Factory Internship ReportAtif MunirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volvo Ec35D: Parts CatalogDocument461 paginiVolvo Ec35D: Parts Cataloggiselle100% (1)

- PanasonicBatteries NI-MH HandbookDocument25 paginiPanasonicBatteries NI-MH HandbooktlusinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Specification For Foamed Concrete: by K C Brady, G R A Watts and Ivi R JonesDocument20 paginiSpecification For Foamed Concrete: by K C Brady, G R A Watts and Ivi R JonesMaria Aiza Maniwang Calumba100% (1)

- Compresores TecumsehDocument139 paginiCompresores TecumsehRicardo EstrellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASTM D 3786 Bursting Strength, Diaphragm MethodDocument1 paginăASTM D 3786 Bursting Strength, Diaphragm MethodAfzal Sarfaraz100% (1)

- VC02 Brass Ball Valve Full Port Full BoreDocument2 paginiVC02 Brass Ball Valve Full Port Full Boremahadeva1Încă nu există evaluări

- أثر جودة الخدمة المصرفية الإلكترونية في تقوية العلاقة بين المصرف والزبائن - رمزي طلال حسن الردايدة PDFDocument146 paginiأثر جودة الخدمة المصرفية الإلكترونية في تقوية العلاقة بين المصرف والزبائن - رمزي طلال حسن الردايدة PDFNezo Qawasmeh100% (1)

- 연대경제대학원 석사학위논문 학술정보원등록 최종본Document121 pagini연대경제대학원 석사학위논문 학술정보원등록 최종본0514bachÎncă nu există evaluări

- K C Chakrabarty: Financial Inclusion and Banks - Issues and PerspectivesDocument9 paginiK C Chakrabarty: Financial Inclusion and Banks - Issues and PerspectivesAnamika Rai PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Information: Reading Images - The Grammar of Visual DesignDocument5 paginiInformation: Reading Images - The Grammar of Visual DesignAndang Prasetya Adiwibawa BernardusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 5 Digital Technology and Social ChangeDocument14 paginiLesson 5 Digital Technology and Social ChangeIshang IsraelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Miqro Vaporizer Owners ManualDocument36 paginiMiqro Vaporizer Owners ManualJuan Pablo AragonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Economic Essentials of Digital StrategyDocument13 paginiThe Economic Essentials of Digital StrategydhietakloseÎncă nu există evaluări