Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Criminology and Criminal Justice 2014 Valverde 379 91

Încărcat de

Héctor Bezares0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

57 vizualizări14 paginiA contribution on the characteristics of a contemporary analytics of security

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentA contribution on the characteristics of a contemporary analytics of security

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

57 vizualizări14 paginiCriminology and Criminal Justice 2014 Valverde 379 91

Încărcat de

Héctor BezaresA contribution on the characteristics of a contemporary analytics of security

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 14

http://crj.sagepub.

com/

Justice

Criminology and Criminal

http://crj.sagepub.com/content/14/4/379

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1748895814541899

2014 14: 379 Criminology and Criminal Justice

Mariana Valverde

Studying the governance of crime and security: Space, time and jurisdiction

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

British Society of Criminology

can be found at: Criminology and Criminal Justice Additional services and information for

http://crj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://crj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://crj.sagepub.com/content/14/4/379.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Aug 20, 2014 Version of Record >>

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Criminology & Criminal Justice

2014, Vol. 14(4) 379 391

The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1748895814541899

crj.sagepub.com

Studying the governance of

crime and security: Space,

time and jurisdiction

1

Mariana Valverde

University of Toronto, Canada

Abstract

That the governance of crime and security often works on and through space is well known by

now; but this article argues that temporality and jurisdiction are equally important dimensions

of law and governance. These three dimensions are not independent, and the article gives some

concrete examples of how temporalization shapes spatialization and in turn interacts with

jurisdiction.

Keywords

Governance of security, jurisdiction, spatialization, temporality

In this article I present an epistemologically modest agenda consisting of sets of ques-

tions that could guide a large variety of research projects on issues of security and crime.

Some of the questions have come out of my own research on legal and governance pro-

cesses, especially urban law and governance, while others are borrowed from the work

of numerous criminologists, sociolegal scholars and others who from different perspec-

tives have developed research questions and analytical tools that are useful for research

on questions of crime, insecurity and security.

It should be noted at the outset that in keeping with the collective consciousness of the

Toronto Centre where I have worked for over 20 years, I focus on what criminology has

or can have in common with sociolegal studies and other traditions of research on gov-

ernance. In other words, whether or not studies of security are part of criminology may

be an important question for those who are explicitly engaged in drawing academic

Corresponding author:

Mariana Valverde, Centre for Criminology & Sociolegal Studies, University of Toronto, 14 Queens Park

Crescent West, Toronto, ON M5S 3K9, Canada.

Email: m.valverde@utoronto.ca

541899CRJ0010.1177/1748895814541899Criminology & Criminal JusticeValverde

research-article2014

Debate Article

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

380 Criminology & Criminal Justice 14(4)

boundaries, but for present purposes, the focus is not on fields or disciplines and their

internal issues. I work instead at a conceptual scale that is concrete and empirically

driven, the scale at which the key object of study consists of governing mechanisms and

the tools we have to analyse them (see Rose et al., 2006).

The gap between criminology and sociolegal studies is nevertheless only bridgeable

in certain places, which limits the applicability of my remarks. The criminological

academy contains both studies of individual psychology and more or less sociological

projects regarding crime in the aggregate, crime prevention, policing and so on. This

article will not be very helpful to the former, that is, to those working at the scale of the

individual and his/her desires, feelings, motives, propensity to commit crime and resil-

ience in the face of victimization. Psychological criminology occupies its own spaces,

both academically and within the state apparatus, and the intellectual (and often politi-

cal) gap between psychological and sociological criminology is much wider, it seems

to me, than that between sociological criminology and sociolegal studies. Thus, the

framework I set out here draws primarily on sociological criminology and on those

sub-literatures in sociolegal studies that document governance and regulation: but in

doing so I have no desire to challenge existing field boundaries or to call for or build a

new interdiscipline. I simply acknowledge that the set of research questions I develop

here come from certain research fields and not others, and it is likely to be most useful

in those enterprises, though of course creative borrowing is always possible and in my

view welcome.

Putting Theory Itself in Question: Some Preliminary

Remarks

But, to take one step back, why do I present a set of questions instead of a theory? As

an official theorist who sometimes publishes in theory journals and has taught theory

courses for 30 years, I am often asked to either endorse one particular existing general

theory of social relations or to elaborate my own. An important reason why I have

chosen to not do theory in the conventional manner is that in my view, macro-

explanations of modernity in general the approach to theorizing that can be said to

begin with Durkheim have less and less purchase on concrete analyses and are

increasingly irrelevant to younger scholars engaged in innovative research. In the

context of studies of crime and security, the key paradigm of theory remains that

drawn from classical sociology. Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens, Zygmunt Bauman,

Manuel Castells and Niklas Luhmann are some of the big names that routinely

appear in the theory section of studies of crime and security. (Foucault does too, but

as I have shown elsewhere his work is generally misused as if it were sociological

theory, so that his work, instead of being used to challenge the paradigm of world-

scale theorizing about modernity, is recuperated by it; see Valverde (2010b).) But

while this established world-scale style of theory is still popular in the sense of being

frequently cited, there are indications that a different kind of work, work that does not

so much critique as eschew and even ignore the formats and the styles of thought of

classical sociology, is on the rise the popularity of Bruno Latour and Actor Network

Theory being perhaps the key clue here (Latour, 2010).

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Valverde 381

Most significantly, while postcolonial studies has not made much of an inroad into

studies of crime and security (postcolonial criminology does not really exist as yet),

criminologists and sociologists who rely on the intellectual habits of the tradition that

goes from Durkheim to such thinkers as David Garland and Ulrich Beck will eventually

have to face up to the fact that what I call world-scale theory was premised on and still

depends on an increasingly problematic assumption, namely, that modernity is the

proper object of social theory. To return to the point (in the late 19th century) when

todays social sciences all took institutional form, sociology could only develop as the

science of modernity by contrast with anthropologys mission to study the primitive.

This means that as the category of the primitive becomes more and more discredited, it

will be increasingly impossible for sociological theory to stick to its old mission state-

ment. Anthropologists have over the past few decades come to grips with the shady his-

tory of their discipline, often painfully, and have developed highly sophisticated

techniques promoting reflexivity and pursuing studies that from the outset challenge the

modern versus primitive binary. Sociology, by contrast, seems not to have heard the

news about the fall of Eurocentric paradigms, and major theorists continue to issue books

that have modernity in the title as if this were a valid category, when in fact modernity

(like the West) is nothing but the Orientalist other of the primitive.

A major reason for the anachronistic persistence of the classical model of social the-

ory, the model that presupposes that there is such a thing as modernity and that this is

social theorys prime object of study, is that scholars who are not sociologists and who

work in interdisciplinary endeavours often look to sociology rather than, say, anthro-

pology or history for theoretical tools (and, worse, models), thus continuing to repro-

duce the style of thought of sociological theory even outside its disciplinary boundaries.

Not coincidentally, sociological geography with a Marxist bent is also popular in todays

supermarket of theory (e.g. David Harvey). Scholars who do not have a vested institu-

tional interest in sociologys claim to be the queen of the social sciences people such as

criminologists, urban studies scholars, public health researchers and so on should find

it easier than those employed in sociology departments to question received assumptions

about what theory is and where it is produced, but for some reason this is not happening.

One reason may be that interdisciplinary scholars hired precisely because of their inter-

disciplinarity are more often than not expected to deliver a curriculum that embodies

antiquated notions of theory, including the separation of official theory courses covering

the canon from topic-oriented courses. This is certainly the case in criminology cur-

ricula that I have seen, not least at my own supposedly world-class institution. Courses

in postcolonial studies and sexuality studies, by contrast, are almost always theoretical as

well as empirical, and while abandoning the theoryresearch binary, they also put in

question the division of intellectual labour between sociology and anthropology that is

constitutive of 20th-century grand social theory. By contrast, criminology and sociology

departments (though British sociology is far less hide-bound than American sociology)

usually cleave to the old idea that theorizing consists of learning the dead white men

canon and that such work is useful to guide empirical research (as opposed to being chal-

lenged by empirical research findings). In sum, therefore, there is ample evidence

though in this article I cannot digress any longer to present it that sociologys

longstanding separation of theory from research sustains a highly abstract, static,

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

382 Criminology & Criminal Justice 14(4)

Eurocentric and masculinist idea of theoretical practice, at the level of form, while at the

level of content, sociology has not yet separated its own self-description from the ques-

tionable Eurocentric category of modernity.

Few young scholars are directly challenging the organization of their departmental cur-

riculum and other practices that embody and reproduce, however implicitly, the anti-

quated notions of theory just canvassed. But more or less quietly, many young scholars are

broadening the scope of what counts as theory. Indeed, canons seem to be steadily losing

ground to new approaches: Actor Network Theory, governmentality studies, science and

technology studies, risk studies and others. These endeavours are not only interdiscipli-

nary but, what is not so often discussed, inter-methodological and inter-theoretical.

The question then is: in this new climate of inter-methodological and inter-theoretical

work, what can people like myself, trained in classical and contemporary philosophy and

theory, offer research? One possibility would be to offer to build yet another, postmod-

ern, abstract model of how the world works. But with all respect to Zygmunt Bauman

and Ulrich Beck, I do not think it makes sense to put new wine in old skins, new content

in the old formats of theory.

This is why I seek not to build a new model or to argue for one of the existing models,

but rather to pose a set of questions that both come out of research and can guide future

research, as I have been doing, in bits and pieces, for the past few years (Valverde, 2009,

2010a, 2011).

The first point which has almost the status of a premise, though not quite is that

asking questions about what is security? or what security ought to be is not very fruitful

for researchers, however satisfying it might be for philosophers. Social scientists make

much more useful contributions when they instead focus on security projects defined

nominalistically as the governing networks and mechanisms that claim to be promoting

security at all scales. And in studying security projects, I argue that it can be useful to

first ask questions about the logic (including the values and telos) of a security project,

and then ask questions about what geographers call scale effects though ensuring that

temporal scale is included in the analysis too, not just spatial scale.

From there, one can move to the somewhat separate question of jurisdiction, which is

almost always taken for granted in criminology. Deciding who governs where the basic

jurisdictional question is not only important in itself but also has the effect of determin-

ing how something is governed. Shifting jurisdiction from one organization or level of

government to another has the effect of automatically changing how something is gov-

erned, as will be shown below.

Finally, it is appropriate to move to documenting the effects of techniques of security

used human, technological, architectural and so on. That will be done in the penulti-

mate section. Certain logics of governance tend to go together with certain techniques,

but this link is not fixed, and so studying the techniques somewhat separately from the

logic, the scale and the jurisdiction can be important.

But to begin it is necessary to address without claiming to answer what most peo-

ple imagine is the basic question: if crime is a negative phenomenon for society as well

as for individuals because it harms security, what is security? Crime is far easier to

define, whether one uses official data about law-breaking or victimization surveys. But

the positive correlate, security, is far harder to grasp.

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Valverde 383

What Is Security?

Unlike lawbreaking, security cannot be seen and measured objectively. The great thinker

of security, Thomas Hobbes, explained the elusiveness of security by pointing out that

what he called war, and we would call insecurity, is not a series of objectively measur-

able events, but rather a tendency, or what would soon come to be called a probability

(and much later, a risk). War, he wrote, consists

not in Battell onely, or the act of fighting, but in a tract of time wherein the Will to contend by

Battell is sufficiently known; and therefore the notion of Time is to be considered in the nature

of Warre, as it is in the nature of Weather. For as the nature of Foule weather lie not in a shower

or two of rain, but in an inclination thereto of many dayes together; So the nature of War,

consisteth not in actual fighting; but in the known disposition thereto, during all the time there

is no assurance to the contrary. All other time is PEACE. (Hobbes, 1968 [1651]: 186, emphasis

added)

A secure commonwealth is thus one in which there may well be some violence or other

anxiety-producing events, but in which people do not have to constantly fear for their

lives and their property as they do in the state of nature. They are secure because they

have agreed to hand over most of their natural liberty to the corporate entity whose task

is to ensure sufficient security so that private individuals can get on with maximizing

their property and their (private, non-political) pleasure. That this security is achieved

only by running the risk of having the sovereign or the state abuse its powers, in ways

which may make individuals quite fearful and insecure, is of course the central paradox

of the social contract, as well as the central paradox of state security, as critics of Hobbes

from John Locke to Edward Snowden have pointed out.

It is this paradox that has been explored by a large number of scholars and public

intellectuals in recent years, in studies that often conclude, as Lucia Zedners (2009: 235)

erudite overview does, that the human need for security should not be permitted to

defeat itself (see also Dillon, 1996; Neocleous, 2008; Wood and Shearing, 2007).

But one can only talk about the human need for security (or for that matter the cen-

tral paradox of security) if one takes security as a single if admittedly fuzzy entity,

such that one can undertake to do a history or a theory of security.

While the theories and histories of security that we now have are certainly useful to

criminology, it may be time to move to a different type of project, one that instead of

focusing on security as a noun, a thing a choice that inevitably leads into normative

discussions about good security versus bad security turns the gaze not on a single word

or a concept but rather on the very wide variety of activities and practices that are being

carried out under the name of security. The shift away from clarifying concepts in the

Oxford tradition to documenting and reflecting on practices is of course Foucaults great

intellectual move. But we can also draw inspiration from a different source, American

legal pragmatism. We can describe what we do as studying what following William

James (1994 [1936]) could be called varieties of security experience. That is, instead of

starting with an abstract noun (security), and proceeding to carry out philosophical or

philological or historical inquiries, we can start with actually existing practices of gov-

ernance that the participants themselves not outside observers describe as promoting

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

384 Criminology & Criminal Justice 14(4)

security in some way. On the basis of that study, we should be able to then draw conclu-

sions about how security is being constituted in a variety of realms.

The conclusions will not have direct political or normative lessons; but they will be

useful for those who want to engage in both practical and intellectual work in the general

area of the governance of security.

The Logic of Security Projects

What I am here calling the logic of a security project which is the substance of the

first research question I suggest we ask draws on Rose and Millers (1992) influential

distinction between political rationalities of governance and technologies of govern-

ance. However, Rose and Miller, and governmentality studies generally, tend to empha-

size the instrumentally rational elements of governance; I use the word logic to include

the affective and aesthetic dimensions of governance.

Criminologists have long pointed out that governing crime, or governing the world

through crime, in Jonathan Simons (2007) influential phrase, are enterprises which are

by no means purely actuarial or rationalistic. Unconscious fears about mythic figures,

racialized demons and assorted folk devils are often contained not only in policing

responses and in correctional practices but even in the criminal law itself, as has been

amply demonstrated by the literature on the US war on drugs, and also by studies of

recent anti-terrorism legislation.

In addition to the well-known affective and aesthetic dimensions of crime control that

derive from fears about the racial Other and the disreputable, the less well-known femi-

nist literature on the gender dimensions of safety, security and risk continues to be highly

relevant today, and it too has drawn attention to the unconscious dimensions of both

perceptions of crime and responses to crime.

So within logic I am including the aims and the assumptions of a project that

which tells us what counts as relevant information but also the culturally specific fears

and moods that pervade the field of security. Mood is important, here: the less than

rational dimensions of policy making are not limited to fear, as in fear of crime crime

control measures can be part of optimistic projects, for example, forms of nationalism.

So what are some examples of what I call the logic of security projects?

Across the street from my house in Toronto there is a public park that is illuminated

until about midnight by very strong lights. These lights, which are bothersome to many

of us but appear to be acceptable and even necessary to those who govern such things,

were initially placed there in the 1950s. Then they were known as morality lights. Now,

nobody calls them that. They are called security lights. The way in which the exact

same entity (bright electric lights in the park) goes by different names at different times

illustrates the way in which one and the same technique can be mobilized by different

logics of security, one geared to securing the moral order by preventing couples from

making out in public versus one focused on stranger danger.

Another example of a simple technique that can be mobilized under quite different

logics is the collection of crime statistics by police district. Those data are generally used

to distinguish good from bad neighbourhoods, for example by real estate agents, or by

the police themselves. The use of those data has then the effect of increasing the

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Valverde 385

socioeconomic differences between neighbourhoods, since the respectable will avoid

buying a house in a bad neighbourhood and the police will likely make fewer stops and

arrests in good neighbourhoods. The logic of such data collection is thus, in this case,

that of increasing urban differentiation the logic of the famous Chicago School circles.

However, district-specific crime data can also be used to counteract increasing social

inequality: they can be used, along with other data, to channel more resources to those

areas that appear to need it most. Thats the welfarist logic of Torontos priority neigh-

bourhoods project, which uses quantitative indicators of disadvantage to funnel more

resources to those areas that need it.

One more example illustrates how logics of governance matter and here, the analyti-

cal point is that one established governing logic can be easily drawn upon, overtly or not,

to support and strengthen the logic of a newer project. Advertisements promoting home

security products suggest that security in this context consists of upholding and increas-

ing the sovereign power of an individual who is always presented as: (a) owning a house,

not renting an apartment; and (b) the head of a family whose other members are always

already nothing but vulnerable victims. Home security marketing gives the impression

that domestic violence does not exist, that the only unruly teenagers are by definition

someone elses children and that the person whose very identity appears to depend on a

mortgage is entitled to monitor and control and literally see every activity of every per-

son who is occupying the household, especially children and domestic workers. One

need not be a declared feminist to appreciate that the logic of home security marketing is

not unrelated to the logic of the patriarchal nuclear family.

Having shown that security projects of all kinds all assume and produce a certain

logic of governance, and that logics can flow from one project to another, we can now go

on to the next set of questions. These have to do with the scale of a security project.

The Scales of Security

That scale matters in both practical security enterprises and in our analyses of these

activities is widely recognized, though often only implicitly. Measures that are consid-

ered appropriate to defend a nation-states borders, for instance, such as an army and an

intelligence service, would not be considered appropriate at the scale of the city or the

neighbourhood.

Theoretical studies of scale shifting and scale issues by geographers such as David

Harvey, Neil Brenner and others have come to be used by criminologists, especially

urban criminologists. I used geographic work on scale myself in an essay included in

Adam Crawfords (2011) edited collection on International and Comparative Criminal

Justice and Urban Governance (see Valverde, 2011). There, I argued that broken win-

dows criminologys choice of scale

2

the microlocal is the key move, since the plau-

sibility of the thesis depends on the rigid exclusion not only of national-scale information

(e.g. about immigration and other demographic changes) but also of city-wide informa-

tion, for example, about deindustrialization.

Most studies of crime and crime prevention choose one particular scale and remain

there throughout the study. Multiscalar analyses are possible (as when ethnographers

look up from their favourite street corner long enough to include broader demographic

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

386 Criminology & Criminal Justice 14(4)

and economic trends in their analyses) but they are not common. That is not necessarily

a problem; what is problematic, I argue, is to proceed without a clear awareness of the

pros and cons of the particular scale we happen to be using.

Scale, however, is more than the amount of space that is included in either the actual

security project at hand or in our analysis. Temporality too which is certainly key to all

security projects including crime prevention, as Thomas Hobbes pointed out is scalar.

The importance of temporal scale choice is visible, for example, in the tensions

between the work of police detectives and those less celebrated officers who engage in

community liaison and crime prevention. Detecting crimes and finding the criminal is a

backward-looking enterprise that treats the present as a vast collection of (a) clues and

(b) witnesses.

3

The logic of detective work deploys the logic that in other work I have

called the forensic gaze (Valverde, 2003), but for present purposes what is important is

that this enterprise has a particular temporality (the retrospective reconstruction of a

crime that took place in the past) and a particular spatialization, focusing on the scene of

crime and radiating out from that.

By contrast, crime prevention work looks to the future rather than the past; but it

also encompasses an indefinite series of possible future events, and in that sense is

broader in both spatial and temporal scope than detective work. The space to be secured

in crime prevention may be relatively small (a house or a park), but the project has to

monitor and guard the whole of that space, without privileging a single scene, as

detective work does.

Temporalizations differ not only by direction (forward versus backward) but in other

ways as well. Henri Bergson famously pointed out that duration the phenomenologi-

cal time of human experience is not the same as objective, calendar time; but more

prosaically, the field of crime and criminal law also contains and relies on temporal dis-

tinctions, such as day/night, weekday/weekend, peacetime/wartime, youth/adulthood

and so on. These distinctions are often embodied in law itself as well as in law enforce-

ment practices.

While I have made a point of highlighting temporal scales, since they have been

wholly neglected both by legal geographers and by criminologists, it is nevertheless

important to remember that in practice temporalizations are not separate from

spatializations it is more useful to think of the local park in need of crime prevention

measures or the murder that needs solving as entities constituted in particular spatio-

temporalities, or what Mikhail Bakhtin (1990) called chronotopes.

Jurisdiction

In many of the examples I have given, the governance issues are not limited to logics and

scale effects, even though that was the focus of the analysis. Scalar effects shade into

jurisdiction: for example, that trash removal is a local issue is both a product of the natu-

ralization of governing scale and a result of the fact that local jurisdiction over waste is

taken for granted, just as jurisdiction over war and peace is assumed to lie with the state,

always and everywhere. The study of jurisdiction does not have to stop with formal law.

There are important jurisdictional divides in non-state or informal systems of govern-

ance, which means that those interested in informal social control and extra-state security

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Valverde 387

should therefore include jurisdiction in their analyses. For example, in many families

mothers and fathers have quite distinct jurisdictions, even though by law they have the

same powers and duties. All manner of other social units, from inmate communities to

organized crime groups to university departments, also rely a great deal on jurisdictional

divisions of labour that may not be visible from the outside but which insiders soon learn

to take very seriously. Informal jurisdictions are by no means remnants of some kind of

traditional past: capitalism constantly gives rise to myriad private or semi-private juris-

dictions, as we see with the rise of international commercial arbitration, Internet law and

other phenomena. Jurisdictional analysis in my meaning of the term thus requires knowl-

edge of law in action, not just law in the books.

Most legal geographers, and some criminologists, conflate jurisdiction with spatial

scale. But even when a jurisdiction coincides with a particular geographic space, juris-

diction is analytically distinct in important ways (Dorsett and McVeigh, 2012; McVeigh,

2007). After all, a murder might take place in a city park, but city bylaw officers have no

jurisdiction over that event.

Even jurisdictions that are territorial rather than functional rarely feature a single

Hobbes-style sovereign. Territories are governed simultaneously by a host of authorities

wielding different jurisdictions, and not only in federal countries. In the urban setting, for

instance, an area in which I have conducted much empirical research, boards and com-

missions are particularly important in the management of everyday disorder, and often

play a more important role than the local authority. Bodies such as parks commissions,

school boards and public transit authorities, not to mention countless quangos and urban

development corporations, exercise jurisdiction over islands of territory within a munici-

pality, though with the island metaphor being inadequate in that these special purpose

bodies are never fully sovereign, and frequently overlap with several other special pur-

pose bodies as well as with political entities from the local authority to the nation state.

Subnational and special-purpose local authorities exist throughout the world, including

in states thought of as highly undemocratic and centralized, such as China. The upshot is

that the Hobbesian model of a single sovereign with a unified, complete jurisdiction has

never existed, even in dictatorships.

Criminologists tend to take jurisdiction for granted, to black box it perhaps because

the criminal law is the least contested of all the jurisdictions one generally finds in stable

democracies. But even though the jurisdiction of national criminal law has been natural-

ized since at least Blackstones day, there are many struggles that show that this jurisdic-

tion too is contested. Medical authorities, for example, are currently, in Canada, arguing

that physician assisted suicide should be removed from criminal jurisdiction and put

under their authority, and the long fight to decriminalize homosexual sex is another

example. While criminologists are quite aware of the struggles over the use of the crimi-

nal law to regulate morality, they rarely pay attention to other actual or potential chal-

lenges to the jurisdiction of the central state, ones that do not have much political traction.

It is taken for granted that municipalities might engage in experiments in enforcement;

but the criminal law itself is assumed to be wholly within state jurisdiction.

Despite the relative success of this black boxing of criminal law jurisdiction, the game

of jurisdiction is nevertheless more complex and unstable than it appears. The instabilities

become particularly visible in the international arena. When Blackwater private contractors

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

388 Criminology & Criminal Justice 14(4)

murdered Iraqi civilians in cold blood in 2007, for example, many were appalled to dis-

cover that the USA had previously passed a law removing their forces of occupation from

all Iraqi jurisdictions. They were even more shocked to discover that because the contrac-

tors were not soldiers they were not subject to the substitute colonial-style jurisdiction of

the Military Extraterritorial Justice statute that had been passed by Congress precisely to

allow the USA to punish soldiers for offences committed abroad. The Iraqi victims, in other

words, were not able to seize on any jurisdiction at all to claim justice. This was not due to

a lack of law in fact, there was an excess of law, with several statutes (e.g. the Alien Torts

Act) hovering in the air alongside Iraqi criminal law and the US statutes mentioned; what

was absent was jurisdiction. As Fleur Johns (2013) important work on the thicket of regu-

lation and law that in fact fills what are thought of as lawless spaces or legal black holes

shows us, studies of state misconduct that invoke Agambens (2005) state of exception

would do better to pay attention to the complex network of overlapping jurisdictions, laws

and regulations that exist even in places like Guantanamo.

Jurisdiction is not just the determination of the who of governance, the determina-

tion of the correct sovereign. Jurisdictional games also determine what spaces, persons

and/or issues are to be governed by any one authority. And perhaps most importantly, in

determining the who and the what of governance, the game of jurisdiction ends up qui-

etly determining the how of governance, the qualitative element. In Canada, if a dispute

about mining is settled in favour of the province, the logic then used to govern will be

that of natural resources, over which provinces have complete jurisdiction. If the dis-

pute is settled in favour of the federal government, then sovereignty will make an appear-

ance, whereas if aboriginal nations are given the legal right to exercise jurisdiction the

logic of conservation and sustainability will then rise to the fore.

Another example: cities in Canada have been arguing that they need to have a say in

immigration policy. If they were successful (highly doubtful), I am sure cities would

govern immigration very differently, using a human-resource model rather than worry-

ing about terrorism.

Thus, who is thought of as the proper authority for space X or problem Y the ques-

tion of jurisdiction ends up settling the often unasked question of how something or

some space is to be governed. And the how of governance is not independent from

questions of space and time. Restorative justice, for example, redefines some crimes as

matters for family-like or community-style governance; and it is not coincidental that

neither the conventional space of criminal justice (the courtroom) nor the conventional

temporalization of criminal punishment (serving time) appear as appropriate.

Techniques of Security

In a complete analysis of a security project one has to pay close attention to the array of

techniques used to implement the project in question. By techniques I do not mean only

technologies such as video surveillance, but also what Actor Network Theory calls tech-

niques of inscription (e.g. writing qualitative reports versus generating a set of num-

bers), as well as what governmentality studies regard as everyday techniques of

governance which includes everything from architectural details characteristic of cer-

tain security institutions to bodily habits.

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Valverde 389

Current journalistic discourse is fixated on communication technologies; we

constantly hear that the Arab Spring would not have happened without social media,

for example. Such technological determinism, however, is not only ahistorical but

also neglects information practices and governing techniques that are not embedded

in or facilitated by machines of one sort of another. Long ago, Ian Hacking (1982)

drew attention to the great importance of the 19th-centurys invention of ava-

lanches of printed numbers as an information format with great effects, and many

studies since have shown the importance of formats that may or may not be con-

nected to hardware.

Thus, when analysing the techniques used to carry out certain security projects we

need to include much more than the equipment. Law itself, I have argued elsewhere

(Valverde, 2009), contains important technicalities that do a great deal of governing

work, even though they are usually neglected not just by criminologists but also by legal

scholars focused on high law and grand legal principles.

Governmentality studies of policing and crime control have explored the effects of

techniques of security in many contexts, paying attention to information formats and

other types of techniques. However, in my view it is dangerous to focus only on tech-

niques. The logic, the spatiotemporal scale and the jurisdiction of the particular security

project being furthered cannot be read off from the techniques. They require separate

analysis.

Conclusion

In my view, the crucial challenge facing theorists today is to finally get over our long-

standing habit of equating theorizing with constructing models. Models of modernity

are particularly problematic from a postcolonial perspective; but assuming that theoriz-

ing equals modelling is problematic more generally. A major problem is that the models

claim to explain or at least describe change but the models are themselves static. The

laws of motion of society, of capitalism, or of neoliberalism, are not themselves

dynamic. This is not surprising. As Nietzsche said long ago, it is not possible for human

thought to be as nimble and mobile as the realities which thought attempts to capture; but

we can at least try for more dynamic approaches in which thought itself, not just history,

is constantly on the move.

Governance projects are, I suggest, more complex than is usually thought. And they

are certainly more complex than their designers realize, since many of the complications

arise from interactions between different dimensions of governance that are often spe-

cific to the situation and cannot be predicted in advance. In some instances jurisdiction

flows from spatial scale; in other cases the game of jurisdiction breaks up space; in some

cases the logic of a project is smoothly promoted by the techniques used, whereas in

other places the techniques end up acquiring a life of their own and undermining the

governing logic. The four sets of questions I have presented here about logic, scale,

jurisdiction and techniques constitute my own attempt to give us tools to do the impos-

sible, that is, to capture in thought, and especially in writing, something of the constantly

shifting reality that is before us.

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

390 Criminology & Criminal Justice 14(4)

Notes

1. This is a lightly edited version of a Public Lecture given at the University of Leeds and it

retains the spoken-word character of the occasion to a large extent.

2. Evident in Wilson and Kellings (1982) original thesis and subsequent debates about its rel-

evance and implications (Sampson and Raudenbush, 1999).

3. Michel Foucaults 1981 lectures on justice, truth-seeking and law, given at the University

of Louvains criminology institute (Foucault, 2014), contain a fascinating reflection on the

origins of the knowledge project Foucault calls the inquiry, a reflection that has the potential

to make a huge contribution to criminological thought. Greek tragedy, and Oedipus Rex in

particular, is presented as the origin of a way of searching for and then certifying knowledge

of who did what that would later develop into legal procedures associated with interrogating

witnesses and using juries (the jury being a modern version of the Greek chorus) to certify

both the truth and the justice of the wrong committed. The inquiry went into decline for

hundreds of years, Foucault claims, but re-emerged in the late middle ages in legal contexts.

Legal or quasi-legal practices of inquiry, Foucault argues, as developed first by the Inquisition

and then by secular justice systems, paved the way for scientific and philosophical inquiries.

References

Agamben G (2005) State of Exception. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bakhtin MM (1990) Forms of time and of the chronotope in the novel: Notes toward a historical

poetics. In: Bakhtin MM The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Holquist M. Trans.

Emerson C and Holquist M. Austin,TX: University of Texas Press, 84258.

Dillon M (1996) The Politics of Security: Toward a Political Philosophy of Continental Thought.

London: Routledge.

Dorsett S and McVeigh S (eds) (2012) Jurisdiction. London: Routledge.

Foucault M (2014) Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling: The Function of the Avowal in Justice. Ed. Brion

F and Harcourt B. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hacking I (1982) Biopower and the avalanche of printed numbers. Humanities in Society 5:

279295.

Hobbes T (1968 [1651]) Leviathan. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

James W (1994 [1936]) The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New

York: Random House.

Johns F (2013) Non-Legality in International Law: Unruly Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Latour B (2010) The Making of Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McVeigh S (ed.) (2007) The Jurisprudence of Jurisdiction. Abingdon: Routledge-Cavendish.

Neocleous M (2008) Critique of Security. Montreal: McGill-Queens Press.

Rose N and Miller P (1992) Political power beyond the state: Problematics of government. British

Journal of Sociology 43(2): 173205.

Rose N, OMalley P and Valverde M (2006) Governmentality. Annual Review of Law and Social

Science 1: 6579.

Sampson R and Raudenbush S (1999) Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look

at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology 105(3): 603651.

Simon J (2007) Governing through Crime. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Valverde M (2003) Laws Dream of a Common Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Valverde M (2009) Jurisdiction and scale: Taking legal technicalities seriously. Social and Legal

Studies 18(2): 139158.

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Valverde 391

Valverde M (2010a) Questions of security. Theoretical Criminology 15(1): 323.

Valverde M (2010b) Spectres of Foucault in sociolegal research. Annual Review of Law and Social

Science 4: 4559.

Valverde M (2011) The question of scale in urban criminology. In: Crawford A (ed.) International

and Comparative Criminal Justice and Urban Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 567586.

Wilson JQ and Kelling G (1982) Broken windows: The police and neighbourhood safety. The

Atlantic Monthly March: 2937.

Wood J and Shearing C (2007) Imagining Security. Collumpton: Willan.

Zedner L (2009) Security. London: Routledge.

Author biography

Mariana Valverde teaches social and legal theory at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal

Studies at the University of Toronto and does research on urban and municipal law and governance.

at Univ of Newcastle upon Tyne on August 25, 2014 crj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- From Governance To Governmentality in CSDP: Towards A Foucauldian Research Agendajcms - 2133 149..170Document21 paginiFrom Governance To Governmentality in CSDP: Towards A Foucauldian Research Agendajcms - 2133 149..170Héctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anger Self AssessmentDocument2 paginiAnger Self AssessmentDaniel Keeran MSWÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foucault and Neoliberalism-A Forum IntroDocument5 paginiFoucault and Neoliberalism-A Forum IntroDisculpatis100% (1)

- FeldmanDocument3 paginiFeldmanHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maize To HazeDocument57 paginiMaize To HazeHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- MACKAY 6000FinalDraft:NeoliberalismDocument47 paginiMACKAY 6000FinalDraft:NeoliberalismHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Spectacle of Violence in Duterte's "War On Drugs", PDFDocument28 paginiThe Spectacle of Violence in Duterte's "War On Drugs", PDFHéctor Bezares100% (1)

- Violence (Definitions)Document5 paginiViolence (Definitions)Héctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Stuart Elden) Terror and Territory The SpatialDocument293 pagini(Stuart Elden) Terror and Territory The SpatialHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rosa Del Olmo - The Ecological Impact of Drug Illicit CultivationDocument10 paginiRosa Del Olmo - The Ecological Impact of Drug Illicit CultivationHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tijuana Case Study Tactics of InvasionDocument6 paginiTijuana Case Study Tactics of InvasionHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space Power and GovernanceDocument7 paginiSpace Power and GovernanceHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSYCHOTOPOLOGIES - Closing The CircuitDocument19 paginiPSYCHOTOPOLOGIES - Closing The CircuitHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Azoulay Ophir Order of Violence - Zone CHDocument41 paginiAzoulay Ophir Order of Violence - Zone CHHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Uses of SidewalksDocument3 paginiThe Uses of SidewalksHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk AssessmentDocument3 paginiRisk AssessmentHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tijuana, Myth and Reality of A Dangerous SpaceDocument19 paginiTijuana, Myth and Reality of A Dangerous SpaceHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- English SpacesDocument15 paginiEnglish SpacesHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Configurations of Space. Time. and Subjectivity in A Coontext of Terror. Colombian ExampleDocument23 paginiConfigurations of Space. Time. and Subjectivity in A Coontext of Terror. Colombian ExampleHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feminist Geopolitics - Unpacking InsecurityDocument9 paginiFeminist Geopolitics - Unpacking InsecurityHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visualizing NarcoculturaDocument13 paginiVisualizing NarcoculturaHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palestine and The War On TerrorDocument14 paginiPalestine and The War On TerrorHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drugs Violence Fear Death Geographies of Death GarmanyDocument20 paginiDrugs Violence Fear Death Geographies of Death GarmanyHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wall, Space and ViolenceDocument9 paginiWall, Space and ViolenceHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multiscale Forest Governance and Violence in GuerreroDocument9 paginiMultiscale Forest Governance and Violence in GuerreroHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- PlaceDocument35 paginiPlaceHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ossman Et Al-2006-International MigrationDocument17 paginiOssman Et Al-2006-International MigrationHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spaces of Terror and RiskDocument6 paginiSpaces of Terror and RiskHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emerging Neoliberal PenaltyDocument41 paginiThe Emerging Neoliberal PenaltyHéctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crane2014 Non-Euclidian Reading Mexico 68Document13 paginiCrane2014 Non-Euclidian Reading Mexico 68Héctor BezaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Peugeot ECU PinoutsDocument48 paginiPeugeot ECU PinoutsHilgert BosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syntel Placement Paper 2 - Freshers ChoiceDocument3 paginiSyntel Placement Paper 2 - Freshers ChoicefresherschoiceÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5b Parking StudyDocument2 pagini5b Parking StudyWDIV/ClickOnDetroitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inspirational Quotes ThesisDocument6 paginiInspirational Quotes Thesisanngarciamanchester100% (2)

- Illustrative Bank Branch Audit FormatDocument4 paginiIllustrative Bank Branch Audit Formatnil sheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2Document16 paginiChapter 2golfwomann100% (1)

- PDEA Joint AffidavitDocument1 paginăPDEA Joint Affidavitlevis sy100% (1)

- Hydrography: The Key To Well-Managed Seas and WaterwaysDocument69 paginiHydrography: The Key To Well-Managed Seas and Waterwayscharles IkeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Herzfeld, Michael - 2001 Sufferings and Disciplines - Parte A 1-7Document7 pagini1 Herzfeld, Michael - 2001 Sufferings and Disciplines - Parte A 1-7Jhoan Almonte MateoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uttara ClubDocument16 paginiUttara ClubAccounts Dhaka Office75% (4)

- Management: Standard XIIDocument178 paginiManagement: Standard XIIRohit Vishwakarma0% (1)

- Electrical Energy Audit and SafetyDocument13 paginiElectrical Energy Audit and SafetyRam Kapur100% (1)

- The First, First ResponderDocument26 paginiThe First, First ResponderJose Enrique Patron GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocument4 paginiRhetorical Analysisapi-495296714Încă nu există evaluări

- Philippine LiteratureDocument75 paginiPhilippine LiteratureJoarlin BianesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aznar V CitibankDocument3 paginiAznar V CitibankDani LynneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Christian WalkDocument4 paginiThe Christian Walkapi-3805388Încă nu există evaluări

- This Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDocument23 paginiThis Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDennys VirhuezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economical Writing McCloskey Summaries 11-20Document4 paginiEconomical Writing McCloskey Summaries 11-20Elias Garcia100% (1)

- Selected Candidates For The Post of Stenotypist (BS-14), Open Merit QuotaDocument6 paginiSelected Candidates For The Post of Stenotypist (BS-14), Open Merit Quotaامین ثانیÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Unrest in Eswatini. Commission On Human Rights 2021Document15 paginiCivil Unrest in Eswatini. Commission On Human Rights 2021Richard RooneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Queen of Kings: Kleopatra VII and the Donations of AlexandriaDocument30 paginiQueen of Kings: Kleopatra VII and the Donations of AlexandriaDanson Githinji EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Signs in The Gospel of JohnDocument3 paginiSigns in The Gospel of JohnRandy NealÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2024 Appropriation Bill - UpdatedDocument15 pagini2024 Appropriation Bill - UpdatedifaloresimeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Wizards' Cabal: Metagaming Organization ReferenceDocument3 paginiThe Wizards' Cabal: Metagaming Organization ReferenceDawn Herring ReedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2003 Patriot Act Certification For Bank of AmericaDocument10 pagini2003 Patriot Act Certification For Bank of AmericaTim BryantÎncă nu există evaluări

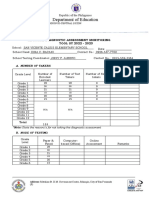

- Regional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Document3 paginiRegional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dina BacaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 50 Compare Marine Insurance and General InsuranceDocument1 pagină50 Compare Marine Insurance and General InsuranceRanjeet SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- B2 (Upper Intermediate) ENTRY TEST: Task 1. Choose A, B or CDocument2 paginiB2 (Upper Intermediate) ENTRY TEST: Task 1. Choose A, B or CОльга ВетроваÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1: Solving Problems and ContextDocument2 paginiChapter 1: Solving Problems and ContextJohn Carlo RamosÎncă nu există evaluări