Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Falsetto

Încărcat de

PaulaRiveroDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Falsetto

Încărcat de

PaulaRiveroDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Voice Pedagogy

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Richard Miller

Falsetto and the Male High Voice

Scott McCoy, DMA

Written questions that teachers and

performers have submitted for discus-

sion at sessions devoted to systematic

voice technique are wide ranging, often

penetrating the very heart of voice ped-

agog.y. This column continues to exam-

ine some of them.

ISSU E

The subject of falsetto arouses

heated discussion among teachers of

singing. The following related ques-

tions often are asked:

Is falsetto any part of the scale that

is not fry or modal register? How is it

produced? Do females have a falsetto?

Can falsetto be incorporated into the

upper range extension of normal male

voice production, for use in public

performance of opera, oratorio, and

recital? Is falsetto identical to male

head voice? If so, why does the coun-

journal of Singing, May/June 2003

Volume 59, No. 5. pp. 405-408

Copyright 2003

National Association of Teachers of Singing

tertenor, whose production is built

largely on falsetto, not sound like a

tenor? What is reinforced falsetto, and

how is it accomplished? Do tenors use

more falsetto than do male low voices?

Does falsetto play a role in voice train-

ing, and if so, in what way? Do you

use falsetto not at all, occasionally, or

often, in your own teaching?

RESPONSE

It has been my privilege for the

past three years to teach courses in

the anatomy and physiology of

singing as part of the professional

development program sponsored by

the New York Singing Teachers

Association (NYSTA). Class mem-

bers include many established voice

professionals who have already accu-

mulated a wealth of knowledge, pri-

marily based on practical experience,

and who now seek formal training in

voice science to reinforce their teach-

ing methods. As we all know, any time

thirty singing teachers are put together

in the same room, livelyif not

heateddiscussions are likely to

ensue. This is certainly the case dur-

ing my courses for NYSTA. Few

issues, however, generate as much

interaction from divergent points of

view as the pedagogical use of falsetto

in the development of the male high

voice.

In my own teaching, falsetto has

been used, albeit sparingly, in three

ways. First, it can help to establish

appropriate vertical positioning of the

larynx. Beginning in falsetto, the stu-

dent sings an easy glissando descend-

ing into his full voice. Early attempts

at this exercise nearly always result

in cracking or yodeling, with a sud-

den leap of a sixth or octave at the

moment of register transition; how-

ever, when the singer learns to stabi-

lize his larynx in a relaxed, slightly

lowered position, a smooth transition

becomes possible. Unless the gentle-

man is training as a countertenor,

there is no artistic motive behind this

exercise. (Except for the occasional

special effect, I do not encourage the

public display of falsetto by operatic

tenors and baritones.) Rather, it is a

pedagogical tool that provides clear

aural feedback, through the presence

or absence of a voice break, about

optimal laryngeal position.

Second, falsetto occasionally is used

to help students find appropriate

vowel modification or "cover" through

the upper passaggio. The ease with

which falsetto tones are produced

allows the singer to concentrate on

vowel sounds and articulatory pos-

tures without the distraction of high

note phobia. The goal, once again, is

to find vowels and postures that opti-

mize full voice singing, not to pro-

duce falsetto tones that are acceptable

in performance. Finally, simple falsetto

exercises (for example, five note

ascending/descending scale patterns)

are used to gently stretch the vocal

ligament, which should ultimately

lead to easier production of higher

tones in the full voice.

In addition to the above techniques,

my colleagues from the NYSTA classes

often vigorously argue in support of

falsetto as a means to discover and

develop the hill male head voice, often

labeled the voce piena in testa. The

most frequent vocalise cited to this

end is a crescendo on a single tone,

MAY/JUNE 2003

405

Scott McCoy

within or above the passaggio, begin-

ning in falsetto and ending in full voice.

I confess to having virtually no prior

success using this method with either

myself or my students, and a brief

review of some of the standard peda-

gogical reference materials from the

past thirty yearsincluding Ware,

Doscher, McKinney, and Miller

reveals no unanimity of support for

the technique.

Some pedagogs [sic] favor the use of falsetto

voice to develop the full head voice, con-

tending that such an approach leads to

more ring and avoids the danger of an

overly dark and weighty sound. They

believe that young voices in particular

have difficulty vocalizing only in ascend-

ing patterns into the passaggio and above,

and that falsetto exercises develop strength

in the cricothyroid stretcher and prevent

the vocalis muscle from over-working.

Other teachers feel equally strongly that

the falsetto has no relation to the full head

voice and that its use as a training device

leads to a thin, overly-bright sound. The

decision must be left to individual teach-

ers and their particular methodology)

Nonetheless, the fact that this method

continues to be employed by respected

and successful teachers motivates me

to additional research and experi-

mentation. My explorations in this

area have been greatly facilitated by

access to advanced voice analysis in-

strumentation, including acoustic spec-

trography and electroglottography

(EGG), found in the Presser Music

Center Voice Laboratory at Westmin-

ster Choir College of Rider University.

According to the advocates of this

technique, it works best when exer-

cises are begun using a reinforced

falsetto. The question therefore arises,

what exactly is a reinforced falsetto?

It is clear in the literature that seman-

tic issues abound in the description

of voice registers. Garcia's historic

use of the term falsetto, for example,

extended to all of the higher tones in

both male and female voices. More

recent pedagogues, such as James

McKinney, attribute falsetto only to

male voices, describing it as "breathy

and flutelike," to be used in male

choirs, yodeling, and for comic ef-

fects. 2 If the community of teachers

and singers cannot agree on a generic

definition of falsetto, how are we to

understand the further refinement of

the term reinforced falsetto?

To me, the term had connoted one

of two things: either the sound pro-

duced by countertenors whose modal

voices lie in the baritone range; or the

loud, clear falsetto timbre employed

by men to impersonate the sound of

women's voices, as exemplified by

members of the New York opera

troupe called La Gran Scena. Few

men, however, can produce a seam-

less crescendo from falsetto to full

voice using either of these vocal tim-

bres. I therefore asked two members

of my NYSTA class who are propo-

nents of this technique for a demon-

stration, one of whom is a gifted

countertenor and capable imperson-

ator of female opera singers. The

sound I heard was not the reinforced

falsetto I had imagined or expected;

instead, it closely resembled the mezza

voce (half voice) or vocejinta (feigned

voice) timbre sometimes heard dur-

ing pianissimo operatic singing.

The physiological and acoustical

foundations of falsetto singing have

been well established by voice scien-

tists. As compared to modal (chest)

register, falsetto is characterized by

reduced closed quotient (the per-

centage of time the vocal folds are

closed versus open during sound pro-

duction, measurable through elec-

troglottography), smaller contact area

between the vibrating vocal folds, lack

of a vertical phase difference between

the bottom and top of the folds dur-

ing oscillation, fewer high frequency

harmonics in the sound spectrum, and

dominance of the cricothyroid mus-

cles in pitch control.

If reinforced falsetto is indeed dif-

ferent from ordinary falsetto, the dif-

ferences should be measurable in the

voice laboratory. To that end, I exam-

ined two tenor voices using EGG and

spectral analysis, a light lyric tenor in

his mid-twenties and a lyrico spinto

tenor with twenty-five years of pro-

fessional singing experience. Each test

subject sang a series of examples that

included sustained tones in quiet, loud,

and reinforced falsetto (or mezza 1 . 0 cC ) ,

and crescendos to full voice, begin-

ning in normal and reinforced falsetto.

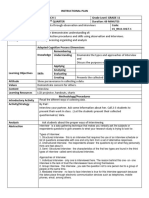

As shown in Figure 1, the reinforced

variant showed higher closed quo-

tients and increased acoustic energy in

high frequency harmonics, indicating

a closer relationship to modal voice.

Both tenors were able to produce a

seamless crescendo out of the rein-

forced sound; however, neither was

able to crescendo from the normal

falsetto without a voice break. Figure

2 shows two attempts at this exercise.

These preliminary results clearly

show acoustic and physiological dif-

ferences between normal and rein-

forced falsetto. The reinforced variant

more closely resembles the full voice

through higher closed quotients and

increased intensity in high frequency

sound components. Since it is known

that the speed and duration of glot-

tal closure directly impact the acoustic

spectrum of the sound produced,' it is

reasonable to speculate that the oscil-

latory pattern of the vocal folds dur-

ing reinforced falsetto also more

closely resembles that of the full voice,

including a degree of vertical phase

difference, which may in turn account

for the greater ease with which a

seamless crescendo can be produced.

Few teachers and students have

ready access to a well equipped voice

406

JOURNAl. OF SINGING

Reinforced

'

f a ls et t o (Tenor A)

402 Hz (approximately (34)

Clos ed quot ient , 53%

k L t w h I : ,

.

I

V

, V

A u d o A 9 m e . ) s l a y 0 . 3 0 m s P i n e d 2 1 9 m e , F l ) 112 H z

J ] [

S p s c t w m ( f r , ) 5 k H z EGG W 9 m s Tne 3 m s C O O 5 3 C L 0 . 3 5

Norma l fa ls et t o (Tenor A )

405 Hz (a pproxima t ely G4)

Clos ed quobent 46%

A u d io B) 9 m s . Wa y 0 . 2 5 m s P OW 2l 7m s , F OI JSHz

S , c t njin( B) 5 k h z I EGG( 8) 9 m s , To * 62 9 m e C Q O 1 6. C L 0 3

Voci Ve t . 2 85

Figure 1. Tenor A s inging in reinforced a nd norma l fa ls et t o. A na lys is windows on

t he left s how t he a cous t ic s pect rum, deoms t ra t ing decrea s ed energy in t he high fre-

quency ha rmonics for norma l fa ls et t o. EGG t ra ces s how a higher clos ed quot ient

a nd fa s t er glot t a l clos ing ra t e for t he reinforced fa ls et t o.

Tenor B: Cres cendo from norma l

fa ls et t o t o full voice

' .

v oi ce B r a "

F d o (A) 9 uw Delay 150Me Pmlod 256 P0303 I

Spedroffm(A) 5 ICinor 1307 me0 1* EGOWS mi ibri 1307 m l COO.CL 035

Tenor A. Crescendo from reinforced

fa ls et t o t o full voice

I50 noPlod 2.24PO447 He

.

fteovarem(B) B *k Cu,o, 1190 mi 0I EGG(B) B ml, 'VIm. 1190 mlCO0.4$. Cl. 0.36

Vccs'i,l. 2.&5

Figure 2. Cres cendo from norma l a nd reinforced fa ls et t o. A voice brea k is vis ible in

t he s pect rogra m of Tenor B (lyrico s pint o v oice).

- Voi ce P e d a gogy

la bora t ory t o explore t hes e differences

in regis t ra t ion. Ma ny t hings ca n be

a ccomplis hed, however, t hrough

s ound a nd s ens a t ion a lone Phys ica lly,

t he reinforced fa ls et t o is likely t o dis -

t inguis h it s elf t hrough a low, rela xed

la ryngea l pos it ion a s oppos ed t o t he

la ryngea l eleva t ion oft en s een wit h

t ra dit iona l fa ls et t o. The t imbre is a ls o

different , wit h t he reinforced s ound

more clos ely res embling t he qua lit y

of t he legit ima t e, a lbeit quiet , oper-

a t ic hea d voice, including a churoscuro

t imbre a nd t he pres ence of high fre-

quency ha rmonic overt ones . The t rue

t es t , however, lies in t he a bilit y t o

cres cendo. Us ing norma l fa ls et t o, it

is pos s ible t o ma ke a fa irly s t rong

cres cendo; t he res ult ing s ound, how-

ever, rema ins in fa ls et t o a nd ma y

clos ely res emble t he t imbre of a

woma n' s voice (unles s it is deliber-

a t ely moved int o t he full voice, which

is us ua lly a ccompa nied by a n obvi-

ous brea k). By cont ra s t , t he cres cendo

from t he reinforced fa ls et t o moves

t ra ns pa rent ly int o t he full voice.

Reinforced fa ls et t o is proba bly not

t he pa na cea ma ny of us ha ve a wa it ed

t o help every ma le s t udent ga in ea s y

a cces s t o his upper regis t er. A s we a ll

know, t he qua lit y of fa ls et t o va ries

grea t ly from s inger t o s inger. I n s ome

it is s t rong a nd elega nt (which might

lea d t o t he a rt is t ic choice t o t ra in a s a

count ert enor); in ot hers it is wea k,

brea t hy, or a bs ent a lt oget her. For t hos e

who a re bles s ed wit h a fa cile fa ls et t o

a nd t he a bilit y t o s elect bet ween it s

norma l a nd reinforced va ria nt s it

ma y indeed s erve a s a pa t hwa y t o t he

t op. I t will cert a inly receive furt her

explora t ion in my own voice s t udio.

NOTES

1. Ba rba ra M. Dos cher, The Functional

Unitij of the Singing Voice (Met uchen,

NJ: The Sca recrow Pres s , 1988), 150.

2. Ja mes C. McKinney, The Diagnosis and

Correction of Vocal Faults (Na s hville,

TN: Genevox Mus ic Group, 1994), 101.

3. Dona ld G. Miller, "Regis t ers in Singing:

Empirica l a nd Sys t ema t ic St udies in

t he Theory of t he Singing Voice"

(Groningen, Net herla nds : The Uni-

vers it y of Groningen, 2000), 167.

4. Joha n Sundberg, The Science of the

Singing Voice (Deka lb, I L: Nort hern

I llinois Univers it y Pres s , 1987), 79.

Scott McCo,y is director of the Presser Music

Center Voice Laborator,j and

Professor

of

MA Y/1 t J NE 20034 0 7

Scott McCoy

ing classes in voice anatomy, physiology, A long-time member ofNATS, McCoy cur- Voice and Pedagogy at Westminster Choir

College ofRider University. He has authored

or coauthored several articles related to

journals, and presented portions of his

multi-media voice science and pedagogy

textbook, Your Voice: An Inside View, at

the 2002 NATS National Convention.

Deeply committed to education, McCoy is

founding faculty member in the New Y ork

Singing Teachers Association (NY STA)

professional development program, teach -

and acoustic analysis.

Jo date, ne has performed more tnan two

dozen leading operatic roles and over sixty

concert and oratorio solo roles with profrs-

sional music organizations in the United

States and abroad. In addition, he is a spe-

cialist in the song cycles of Schubert and

Schumann, frequently concertizing with

pianists Claude C,ymmnan andj.J. Penna.

rently serves the organization as Vice Pres-

ident for Workshops and as a member of

the Editorial Board ofthejournal of Sing-

ing. Prior tojoining the Westminster faculty

in 1997, he was chair of Voice and Opera

at the University of Iowa. When not teach-

ing, singing, or writing, he might beJbund

working on one of his vintage British sports

cars, including a 1952 MG-TD anda 1970

Jaguar XKE.

singing that have appeared in prestigious McCoy maintains an active si ngi ng career.

The National Association of Teachers of Singing, Inc.

announces a

Call for Performances of Vocal Chamber Music

for the

48

1h

National Convention in New Orleans

July 8-12, 2004

The 48" National NATS Convention wi//feature vocal chamber music representative of all voice types

and instrument groups. Total performance time Jor each piece selected, including an y explanatory com-

ments, will he twenty minutes. Selected performers will chose*hy acommittee employing a blind

review process.- -

If y ou are interesled !ffJWrJVming a composition for voice and insrrunu'nt(s), including chamber en-

sembles, at the New Orleans NATS convention in 2004 please submit the following materials:

1. A recent recording (CI) or cassette) of the clected composition by the submitting performers.

The performance. including a briel lecture presentation, should not exceed twent y minutes.

2. A brief ahstrcr describing the.pie'e and the instrumentation.

3. Brief biogrhies of the pezfovnierc amid/or ensemble.

Please send y our submission or an' quesdbiisfu the address !ow.

Submission Deadline: June 1, 2003

Schar mal Schr ock, Pr ogr am Chair man

85) 549-236

SLU Box 10815

s s chr ock@ s e lu . e d u

Sou the as te r n Lou is iana Unive r s ity

Hammond , LA 70402

408

JOURNAl. OF SINGING

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Harriet AbramsDocument2 paginiHarriet AbramsPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abing (Hua Yanjun) : BibliographyDocument2 paginiAbing (Hua Yanjun) : BibliographyPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Otto AbrahamDocument3 paginiOtto AbrahamPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Versatile Singer - A Guide To Vibrato & Straight ToneDocument127 paginiThe Versatile Singer - A Guide To Vibrato & Straight TonePaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paul AbrahamDocument2 paginiPaul AbrahamPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABOSDocument3 paginiABOSPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbondanteDocument2 paginiAbondantePaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Claudio AbbadoDocument3 paginiClaudio AbbadoPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abingdon, 4th Earl of (Bertie, Willoughby)Document3 paginiAbingdon, 4th Earl of (Bertie, Willoughby)PaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- H AbertDocument4 paginiH AbertPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Abell 1Document4 paginiJohn Abell 1PaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbbatiniDocument5 paginiAbbatiniPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbbeyDocument2 paginiAbbeyPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbelardoDocument2 paginiAbelardoPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pietro AaronDocument5 paginiPietro AaronPaulaRivero100% (1)

- Ernest ClossonDocument2 paginiErnest ClossonPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eagles, The.: California. The Next Album, The Long Run (Asylum 1979), WasDocument2 paginiEagles, The.: California. The Next Album, The Long Run (Asylum 1979), WasPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flädermöss: Arr: Eva Toller 2009 Text: Anna Maria Roos Musik: Sigurd Von KochDocument4 paginiFlädermöss: Arr: Eva Toller 2009 Text: Anna Maria Roos Musik: Sigurd Von KochPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adrienne ClostreDocument2 paginiAdrienne ClostrePaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Latin Secular SongDocument10 paginiEarly Latin Secular SongPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Vocal Pedagogy WorkshopDocument41 paginiThe Vocal Pedagogy WorkshopPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reconstructing MozartDocument20 paginiReconstructing MozartPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vocal Recovery TitzeDocument2 paginiVocal Recovery TitzePaulaRivero100% (1)

- Cluniac MonksDocument6 paginiCluniac MonksPaulaRiveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Importance of Observing A ClassDocument2 paginiImportance of Observing A Classmarcos1008Încă nu există evaluări

- ADEC - Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Arab Pakistan School 2016-2017Document23 paginiADEC - Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Arab Pakistan School 2016-2017Edarabia.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Justin Davenport - Teacher Retention in The United StatesDocument19 paginiJustin Davenport - Teacher Retention in The United Statesapi-310209692Încă nu există evaluări

- ReferencesDocument5 paginiReferencesLiezel Cagais SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tracy Safe School Plan 2013Document7 paginiTracy Safe School Plan 2013api-26873415Încă nu există evaluări

- GSP Action Plan 2016-2017Document4 paginiGSP Action Plan 2016-2017Gem Lam Sen100% (4)

- Comparatives and Superlatives AdjectivesDocument17 paginiComparatives and Superlatives AdjectivesAraceli De la CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher Leadership in Pre-Service Education and The Philippine Professional Standard For TeachersDocument4 paginiTeacher Leadership in Pre-Service Education and The Philippine Professional Standard For TeachersRoger Yatan Ibañez Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- CS RS11 IVd F 1Document4 paginiCS RS11 IVd F 1Alvin Montes83% (6)

- Student Handbook 2008-2009Document12 paginiStudent Handbook 2008-2009atrombleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philip Callan: Student Leadership ExperienceDocument2 paginiPhilip Callan: Student Leadership ExperiencePhil LouisÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL G9.PE.Q4.week1Document7 paginiDLL G9.PE.Q4.week1Kenneth Dumdum Hermanoche100% (1)

- Running Head: Teaching Strategies in Nursing Education 1Document19 paginiRunning Head: Teaching Strategies in Nursing Education 1api-396212664Încă nu există evaluări

- Beg Drama Disclosure DocumentDocument3 paginiBeg Drama Disclosure DocumentKris JenningsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manual On Test Item Construction TechniquesDocument60 paginiManual On Test Item Construction Techniquesenzan_ijuin100% (2)

- Michael Triplett ResumeDocument3 paginiMichael Triplett ResumeMichael TriplettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Click Clack Moo Lesson Plan FinalDocument6 paginiClick Clack Moo Lesson Plan Finalapi-313048866Încă nu există evaluări

- Functions Introduction LessonDocument4 paginiFunctions Introduction Lessonapi-252911355Încă nu există evaluări

- School ProfileDocument15 paginiSchool ProfilePaul Romano Benavides RoyoÎncă nu există evaluări

- McDonough C01Document14 paginiMcDonough C01Dharwin GeronimoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education Policies For Students With DisabilitiesDocument379 paginiEducation Policies For Students With DisabilitiesNicoleta IladeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Theories PaperDocument3 paginiLearning Theories PaperryanosweilerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9700 m18 Ms 12 PDFDocument3 pagini9700 m18 Ms 12 PDFIG UnionÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL New GRADE 1 To 12 With SampleDocument15 paginiDLL New GRADE 1 To 12 With SampleYeshua YeshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2007 Teaching and Learning Ontology and Epistemology in Political ScienceDocument9 pagini2007 Teaching and Learning Ontology and Epistemology in Political ScienceCarlos Frederico CardosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLP - GRADE 10 ArtsDocument2 paginiDLP - GRADE 10 ArtsErika Leonardo100% (1)

- Overview of Year 6 KSSR English 2015Document35 paginiOverview of Year 6 KSSR English 2015Rafiza Mohd SanusiÎncă nu există evaluări

- A High School Chronicle - Enchanting MemoirsDocument7 paginiA High School Chronicle - Enchanting MemoirsSadaf FayyazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Library ProposalDocument11 paginiLibrary ProposalwhimiscallibrarianÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dialogue Below Is For Questions No. 1-3Document5 paginiThe Dialogue Below Is For Questions No. 1-3Wina Aleyda PutriÎncă nu există evaluări