Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

PNAS 2012 Davidai 15201 5

Încărcat de

Maria PappaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

PNAS 2012 Davidai 15201 5

Încărcat de

Maria PappaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The meaning of default options for potential

organ donors

Shai Davidai

a,1

, Thomas Gilovich

a

, and Lee D. Ross

b,1

a

Department of Psychology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; and

b

Department of Psychology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305

Contributed by Lee D. Ross, July 30, 2012 (sent for review May 8, 2012)

Rates of participation in organ donation programs are known to

be powerfully inuenced by the relevant default policy in effect

(opt-in vs. opt-out). Three studies provide evidence that this

difference in participation may occur in part because the require-

ment to opt-in or opt-out results in large differences in the mean-

ing that individuals attach to participation. American participants

in Study 1 rated participation as a signicantly more substantial

action when agreement was purportedly obtained under opt-in

rather than opt-out conditions, and nonagreement as a greater

abrogation of responsibility when that decision was made under

opt-out rather than under opt-in conditions. Study 2 replicated

these ndings with respondents who live in Germany, which

employs an opt-in donation policy, and in Austria, which has an

opt-out policy. Study 3 required American participants to rate var-

ious actions that differ in the effort and self-sacrice they demand.

As predicted, the placement of organ donation on the resulting

multidimensional scaling dimension differed signicantly depend-

ing on whether it purportedly was made in an opt-in country

(where it was considered roughly akin to giving away half of ones

wealth to charity upon ones death) or an opt-out country (where it

fell between letting others get ahead of one in line and volunteer-

ing some time to help the poor). Wediscuss therelationshipbetween

this change of meaning account and two other mechanismsbehav-

ioral inertia and implicit normsthat we believe underlie the default

effect in decision making and other effects of policies designed to

inuence decision-makers.

default options

|

opt-in vs. opt-out

|

subjective meaning

|

construal

A

large body of recent research has called into question the

fundamental assumption of classical economics that people

have stable and well-articulated preferences that guide their

choices (1). This research demonstrates that peoples preferences

can be dramatically inuenced by minor variations in the phrasing

of a question or by the method by which they are elicited. Such

ndings, in turn, suggest that preferences often are constructed on

the spot and in light of the surrounding context (26). This recog-

nition of the context-dependent nature of judgments and the con-

structed nature of preferences has led to calls for public policy

reform that takes into account both the lability of peoples

responses and various judgment and decision biases to which

people are prone (79). Indeed, an inuential book by the behav-

ioral economist Richard Thaler and the legal scholar Cass Sunstein

(10) argues that peoples susceptibility to subtle inuences of the

sort that social and cognitive psychologists have explored during the

last few decades should be used to inuence people to act in ways

that advance the public good without harmto those individuals and

without compromising their freedom and autonomy.

A topic of special interest among social scientists and others

concerned with public policy has been the impact of default

options (i.e., what happens when individuals take no action with

regard to a particular choice opportunity). This interest has been

fueled in part by the dramatic results of a study of organ donation

volunteer rates across various European countries (11). Some

countries (e.g., Germany and The Netherlands) have explicit

consent, or opt-in, policies whereby citizens must indicate their

willingness to have their organs harvested in the event of a fatal

accident. Other countries (e.g., Austria and Belgium) have pre-

sumed consent, or opt-out, policies whereby citizens must in-

dicate their unwillingness to participate. This difference across

countries provides a very telling natural experiment.

The difference in organ donation ratestypically exceeding

90% in opt-out countries and failing to reach even 15% in opt-in

countriesastonishes most readers. The authors of the landmark

study and those who cite it in advocating a switch from opt-in to

opt-out default policies attribute this pronounced discrepancy to

the difference in relative effort and initiative required for partic-

ipation. They note that defaults impose physical, cognitive, and in

the case of donation, emotional costs on those who must change

their status (ref. 11, p. 1339). In other words, it simply is easier for

a willing participant to be registered as a potential organ donor in

an opt-out country than in an opt-in country. The authors were

careful to point out other factors, beyond ease of enrollment, that

contribute to this difference, noting that decision-makers might

believe that defaults are suggestions by the policy maker, which

imply a recommended action (ref. 11, p. 1338 and ref. 12) and

that defaults often represent the existing state or status quo and

. . . psychologists have shown that losses loom larger than equiv-

alent gains (ref. 11, p. 1338).

Although we agree that all three of these factors contribute to

the dramatic difference in participation rates in opt-in vs. opt-out

countries, we believe that another powerful determinant is key to

a fuller and more general understanding of the circumstances in

which seemingly small variations in the presentation of behav-

ioral options produce such large effects. We contend that dif-

ferent default policies inuence the very meaning that people

assign to the act of being an organ donor. The act of signing or

not signing the back of ones drivers license, we suggest, is con-

strued very differently in an opt-in vs. an opt-out context. In the

opt-in case, the question posed to potential donors is something

akin to, Do you want to put yourself forward as an exceptional

altruist, someone who acts for the good of others under circum-

stances when only particularly virtuous fellow citizens are likely

to follow suit? In an opt-out context, in contrast, the implicit

question is something akin to, Do you want to stand out as an

exceptional misanthrope, someone who fails to step forward and

do ones duty as most good citizens and community members do?

Our contention is consistent with a long tradition in social

psychology that emphasizes the importance of subjective meaning

and the degree to which individual and collective interpretations

of prevailing circumstances, and not the objective circumstances

themselves, determine peoples behavior (13). This tradition ex-

plores the impact of the social and situational context on how

meaning is derived and, in the words of pioneering social psy-

chologist Solomon Asch, focuses not on the individuals judg-

ment of the object but on the individuals construal of the object

of judgment (14). In Aschs famous example, the meaning assigned

Author contributions: S.D., T.G., and L.D.R. designed research; S.D. performed research;

S.D. and T.G. analyzed data; and S.D., T.G., and L.D.R. wrote the paper.

The authors declare no conict of interest.

Freely available online through the PNAS open access option.

1

Towhomcorrespondence may be addressed. E-mail: sd525@cornell.eduor lross@stanford.edu.

www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1211695109 PNAS | September 18, 2012 | vol. 109 | no. 38 | 1520115205

S

O

C

I

A

L

S

C

I

E

N

C

E

S

to the term rebellion in the assertion that a little rebellion now

and then is a good thing means something very different to lis-

teners who have been told that it was uttered by Thomas Jef-

ferson than to those led to believe it was uttered by Vladimir

Ilyich Lenin (15). Similarly, Asch argued, the meaning of the term

politician prompts people to consider very different exemplars

(great statesmen such Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, or

Winston Churchill) when they believe their peers have ranked

that calling very highly than when they believe their peers have

ranked it rather low on a list of occupations (in which case they

think of corrupt political bosses or ofce-holders who will say or

do anything to win an election) (16).

Reared in this subjectivist tradition, social psychologists have

been conditioned to suspect the inuence of differences in sub-

jective interpretation whenever they observe an especially powerful

effect of seemingly minor differences in wording, framing, or social

context. The effect of default policies on donor participation rates

is a case in point. We pursue that idea in a series of experiments

designed to examine whether the meaning people assign to organ

donation is very different in an opt-in systemand an opt-out system.

Experiments 1A and 1B: Meaning of Agreeing and Not

Agreeing to Donate

Two initial studies provided strong and straightforward support

for our central thesis. These studies show that the prevailing

default policy in a given country inuences a potential donors

decision whether or not to participate, in part because it in-

uences the meaning citizens assign to that decision. In ex-

periment 1A, American participants were found to believe that

agreeing to be an organ donor represents a signicantly more

substantial action when the country in question was said to use

an opt-in policy rather than an opt-out policy, Mean

opt-in

= 5.9,

M

opt-out

= 4.9, t(160) = 4.38, P < 0.0001 (Fig. 1A). That is, in

an opt-in country organ donation is seen as more like leaving

A B C

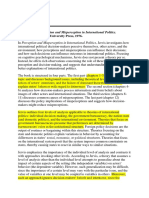

Fig. 1. (A) Judged similarity of organ donation to

a set of high-cost/high-involvement actions (e.g.,

donating 20% of ones income to charity) vs. low-

cost/low-involvement actions (e.g., donating 2% of

ones income to charity) by United States partic-

ipants regarding an unnamed opt-in or opt-out

country. (B) Judged similarity of organ non-dona-

tion to relatively substantial/uncommon negative

behaviors (e.g., reporting false information on ones

tax return) vs. nonsubstantial/common behaviors

(e.g., failing to report some income on ones tax

return). (C) Judged similarity of organ donation to

relatively high-cost/high-involvement actions and

low-cost/low-involvement actions by residents of an

opt-in or opt-out country.

Fig. 2. Multidimensional scaling solution of ratings of the similarity of nine behaviors in an opt-in vs. opt-out country.

15202 | www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1211695109 Davidai et al.

50% of ones estate to charity than like leaving 5% and more like

taking part in a political campaign than like voting for mayor.

Conversely, in experiment 1B, participants thought that not

agreeing to be an organ donor was more meaningful when the

country was said to have an opt-out policy rather than an opt-in

policy, M

opt-in

= 4.9, M

opt-out

= 5.3, t(41) = 2.57, P = 0.014 (Fig.

1B). That is, in an opt-out country, not agreeing to be a donor is

seen as more like skipping your childs graduation than like

skipping your childs baseball game and more like belittling

someone who tried hard and failed than like not being supportive

of someone who did so.

Experiment 2: Meaning of Agreeing to Donate in Austria and

Germany

Study 2 replicated these ndings with respondents who actually

live in countries with opt-in or opt-out organ donation policies.

Participants in Germany, which employs an opt-in policy, found

the act of agreeing to donate ones organs in the event of ones

death to be relatively meaningful and substantial (akin to working

overtime without compensation or to giving 20% of ones annual

income to charity). Participants in Austria, a country with a very

similar culture and ethnic heritage but that employs an opt-out

policy, found the act of agreeing to be a donor relatively lacking in

meaning and rather insubstantial (akin to fullling ones duties at

work or giving 2% of ones annual income to charity), M

Germany

=

5.1, M

Austria

= 4.2, t(43) = 2.64, P = 0.011 (Fig. 1B).

Experiment 3: Placement of OrganDonationon the Continuum

of Altruistic Actions in Opt-In vs. Opt-Out Countries

Experiment 3 replicated our ndings with a very different mea-

sure of meaning. In this study, American participants read about

a foreign countrys opt-in (The Netherlands) or opt-out (Bel-

gium) organ donation policy and then rated how similar a variety

of different prosocial behaviors, including the decision to be a

potential organ donor, are to each other in terms of their signi-

cance and the level of sacrice they entail. Some of the behaviors

involved a great deal of effort or self-sacrice (e.g., going on a

hunger strike for an important cause or volunteering for a dan-

gerous military assignment), whereas others involved relatively

little effort or self-sacrice (e.g., casting a vote in a mayoral elec-

tion or letting others go ahead in line).

As predicted, the default donation policy of the country in

question had a signicant effect on the way participants rated the

act of organ donation. Those asked to think about a country with

an opt-in policy judged organ donation to be much more similar to

the other highly meaningful and signicant prosocial behaviors

(M

similarity

= 5.4) than to the less meaningful and signicant

actions (M

similarity

= 3.1), paired t(50) = 9.64. By contrast, those

asked to think about a country with an opt-out policy rated organ

donation as slightly (although not signicantly) more similar to the

prosocial actions that were relatively low in meaningfulness and

signicance (M

similarity

= 4.6) than to the actions that were rela-

tively high in meaningfulness and signicance (M

similarity

= 4.1).

The relevant interaction effect reecting the difference in partic-

ipants placement of organ donation on the effort/self-sacrice

continuum was highly signicant, F(3,194) = 15.25, P < 0.001.

The different meaning that the two groups assigned to the act of

organ donation can be seen clearly in Fig. 2. In an opt-in country,

a willingness to donate ones organs is seen as roughly akin to giving

away half of ones wealth to charity upon ones death and as being

almost equivalent to going on a hunger strike in support of a cause

one advocates. In an opt-out country, in contrast, organ donation is

seen as quite far from such relatively extreme acts of altruism,

falling between letting others get ahead of one in line and volun-

teering some time to help the poor. None of the other prosocial

acts, it is worth noting, were evaluated differently in the two

countries, a result that attests to the specicity of the effect in

question and helps us rule out alternative explanations involving

participants assumptions about more general cultural differences.

Discussion

In considering the enormous differences in organ donation rates

between opt-in and opt-out countries, the surprise one experiences

does not arise from the fact that different default policies are as-

sociated with different percentages of potential donors. The sur-

prise is that the effect is so large. Indeed, in addition to the measures

reported above, participants in study 1A were asked to estimate the

percentage of the adult population whose organs would be eligible

for harvesting in an unnamed opt-in or opt-out country. The pre-

dicted rate was 45% for the opt-in country and 63% for the opt-out

country, a difference that is statistically signicant but much smaller

than the actual differences documented by researchers (11). Clearly,

our participants, and we suspect most people, are missing something

important when they make such predictions and are surprised by the

actual donor participation rates in countries that seem so similar in

ethnic makeup, national ethos, and apparent underlying values.

One possibility is that people are simply lazier or perhaps more

prone to procrastination (that is, they simply do not get around to

doing something they are quite willing or inclined to do) than most

of us generally recognize. We do not doubt that this is the case.

However, our ndings make it clear that another factor is also at

play: Participation or nonparticipation of individual citizens is

heavily inuenced by the meaning that people individually and

collectively attach to the opt-in or opt-out choice in question. When

citizens are presumed by the default option to be organ donors,

organ donation is seen as something that one does unless some

exceptional factor makes an individual particularly reluctant to

participate. In contrast, when citizens are presumed by the default

option not to be organ donors, organ donation is seen as something

noteworthy and elective, and not something one simply does.

Our research shows that when respondents are asked explicitly to

consider the meaning of the relevant choices, they are capable of

discerning this difference in meaning. The failure to make more

accurate predictions about the difference betweenopt-inandopt-out

participation rates therefore must arise from one of three reasons.

Respondents may not spontaneously consider these differences in

meaning, they may not discern the degree of difference in meaning,

or they may not appreciate how much impact the difference in

meaning will have relative to other determinantssuch as individual

differences in personal traits and valuesin producing the relevant

donation rates. Whether participants would predict differences in

participation rates more accurately if they were asked to do so after

having assessed the meaning of organ donation in the two different

contexts is an interesting question and has some theoretical rele-

vance. It is not, however, the one we sought to address in our study.

Again, we emphasize that we are not claiming that differences

in the meaning of the object of judgment represent the only

factor responsible for differences in organ donor volunteer rates.

Indeed, we do not even claim that such differences are the most

important cause of the observed differences in opt-in and opt-

out countries. That designation may well belong to sheer inertia

and the need to do something to become a volunteer vs. the need

to do something to avoid becoming a volunteer.* Our contention

*Although one cannot manipulate a default option without manipulating potential

meaning, Johnson and Goldstein (11) have shown that presenting the relevant options

in a way that controls for possible inuences of laziness and inertia does not eliminate

the effect of defaults. That is, they asked research participants whether they would be

a donor: (i ) if they moved to a country in which the default was not to be a donor and

they had to afrm or reject the prevailing opt-in default; (ii ) if they moved to a country

in which they were assumed to be a donor and they had to afrm or reject the opt-out

default; or (iii ) they had to choose to be a potential donor or not, with no default

specied. Notably, twice as many participants afrmed their willingness to be a potential

donor in the opt-out condition even though a simple click of the mouse was the only

effort required in all three conditions.

Davidai et al. PNAS | September 18, 2012 | vol. 109 | no. 38 | 15203

S

O

C

I

A

L

S

C

I

E

N

C

E

S

is simply that the way options relevant to personal and societal

decisions are posed inevitably inuences the meanings that be-

come attached to those decisions.

Furthermore, differences in meaning may inuence (and in

turn be inuenced by) other determining factors, perceived norms

in particular. In fact, numerous investigators have shown that

perceived norms can have a very largeand often under-

estimatedimpact on peoples choices and decisions (1720).

The tendency to assume that the default says something about the

preferences or implicit recommendations of those who set the

policy (12) can have a similar effect, leading people to assume

that others will heed the implicit recommendation, thereby

inuencing their assessment of the societal norm.

Although these different mechanismsinertia, meaning, as-

sumed norms, and implicit recommendationsoften are mutu-

ally reinforcing, they sometimes can be at odds with one another.

When they are in conict it is especially important to attend to

the meaning that people are likely to assign to opting-in vs.

opting-out. For example, imposing a penalty on behavior one

would like to discourage, such charging a fee for parents arriving

late to pick up their children from day care, might seem like

a sensible policy because it makes the behavior more costly.

However, if people think of it as a price instead of a penalty, it

paradoxically can produce more of the very behavior one wants

to discourage (21). To craft the most effective policies, therefore,

it is essential that policy makers attend to the meaning people

will assign to different actions, a lesson we have tried to highlight

with the research reported here.

Methods

This research was approved by Cornells Institutional Review Board and all

participants provided informed consent.

Experiment 1A. Participants and design. Participants were 163 students at

Cornell University (87 women and 76 men; M

age

= 19.88 y) who were

approached on or near the campus and who volunteered to complete a

short survey. They were assigned randomly to one of the two experimental

conditions.

Manipulation. Participants read a short paragraph describing the organ do-

nation policy of a foreign country. They learned either that the country had

an opt-in policy, in which the default assumption of the countrys health

system is that the person [. . .] is not willing to have his or her organs do-

nated or an opt-out policy in which the default assumption of the coun-

trys health system is that the person [. . .] is willing to have his or her

organs donated.

Dependent variables. Following the manipulation, participants were asked to

consider what it means to donate ones organs in the aforementioned

country. Specically, participants were asked to evaluate the act of organ

donation in this country on seven different bipolar scales. On each scale,

participants selected the appropriate value along a nine-point continuum

representing the similarity of organ donation, in terms of effort and sig-

nicance, to two other activities, e.g., paying ones taxes vs. endowing a

small public-works project, or voting for mayor vs. taking part in a local

political campaign.

We averaged participants ratings across all seven scales

( = 0.82) to create a composite measure of donation meaning, in which

higher numbers indicate a greater degree of effort and signicance attrib-

uted to organ donations.

Experiment 1B. Participants and design. Participants were 43 students at Cornell

University (24 women and 19 men; M

age

= 19.05 y) who completed a survey

as part of a packet of questionnaires in exchange for extra credit. They were

assigned randomly to one of the two experimental conditions.

Manipulation. Participants read the same manipulation as in experiment 1A,

describing a country with an opt-in or opt-out organ donation policy.

Dependent variables. Following the manipulation, participants were asked to

consider what it means not to donate ones organs in the aforementioned

country. Specically, participants were asked to evaluate the act of not do-

nating ones organs in this country on seven bipolar scales by selecting the

appropriate value on a nine-point continuum between two other activities,

e.g., failing to report some income on your tax return vs. reporting false

information on your tax return, or looking after your own interest vs. being

selsh.

As in study 1A, we averaged participants ratings across all seven

scales ( = 0.74) to create a composite measure of the meaning of non-

donation, in which higher numbers indicate greater signicance attached to

the failure to donate.

Experiment 2. Participants and design. Participants were 45 respondents (11

women and 34 men; M

age

= 30.36) from Amazons Mechanical Turk, a

website that links researchers with individuals who participate in research

for a nominal fee. Participants were citizens of Germany (a country with an

opt-in organ donation policy) or Austria (a country with an opt-out organ

donation policy).

Dependent variables. Participants were told that different countries have

different organ donation policies and that the researchers were interested in

how people in their country view the act of organ donation. They then were

asked to complete the same task as in experiment 1A, evaluating the simi-

larity of organ donations in their country to each of seven pairs of prosocial

actions varying in signicance. We averaged the ratings of all seven items ( =

0.72) to create a composite measure of the meaning of donation, with

higher numbers indicating a greater degree of effort and signicance at-

tributed to the act of organ donation.

Experiment 3. Participants and design. Participants were 101 students at Cornell

University (57 women, 42 men, 2 unspecied; M

age

= 19.49 y) who completed

an online survey and were assigned randomly to one of the two experimental

conditions.

Manipulation. Participants read a short paragraph describing the organ do-

nation policy in The Netherlands (an opt-in policy) or Belgium (an opt-

out policy).

Dependent variables. Following the manipulation, participants were asked to

consider how a variety of different prosocial actions are perceived in the

country they read about, in terms of signicance or sacrice. There were nine

items altogether, involving varying degrees of effort, signicance, or sacri-

ce, including voting for mayor, letting other people go ahead of you in line,

volunteering your time working with the poor, and donating your organs

when you die.

Participants rated the similarity of each possible pair of items,

or 36 different comparisons altogether, on a nine-point scale (1 = not at all

similar; 9 = highly similar).

Within each condition, we averaged the rated similarity of organ donation to

the ve highly signicant prosocial actions (

Opt-out

= 0.79,

Opt-in

= 0.66)

to create a composite measure of similarity to highly signicant actions; we also

averaged the rated similarity of organ donation to the three less signicant

prosocial actions (

Opt-out

= 0.80,

Opt-in

= 0.60) to create a composite measure of

similarity to less signicant actions.

{

In both cases, higher numbers indicate

greater similarity to the actions in question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. We thank Yoel Inbar for his help and generosity with

data collection. Funding was provided by National Science Foundation Grant

SES-0922323.

The other pairs were: fullling ones duties at work/working overtime without compensation;

giving 2% of ones annual income to charity/giving 20% of ones annual income to charity;

coaching your sons baseball team/coaching a local baseball team without having a child on

the team; leaving 5% of ones estate (upon death) to a specied charitable cause/leaving 50%

of ones estate (upon death) to a specied charitable cause; keeping the neatness of ones

house and yard to the standard of the neighborhood/volunteering at a local initiative to clean

up the neighborhood.

The other pairs were: not being supportive of someone who tried hard but failed/belit-

tling someone who tried hard but failed; not helping a friend prepare for a quiz on a

subject you know well/not helping a friend prepare for a nal examination on a subject

you know well; forgetting a colleagues birthday/forgetting your mothers birthday;

putting others at risk of getting a cold you do not know you have/putting others at risk

of getting a cold you do know you have; skipping your childs baseball game/skipping

your childs graduation.

The other items were paying your taxes, giving away half your wealth to charity when

you die, going on a hunger strike for a cause you strongly believe in, intervening to help

someone who is being verbally assaulted, and volunteering for a dangerous

military assignment.

{

We split the prosocial behaviors according to the results of the Multidimensional Scaling

solution. We had chosen the items so that there would be four highly signicant items

and four less signicant items, but participants rated volunteering your time to help the

poor as more substantial/signicant than we anticipated.

15204 | www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1211695109 Davidai et al.

1. Friedman M (1953) Essays in Positive Economics (Univ of Chicago Press, Chicago).

2. Gilovich T, Grifn DW (2010) Judgment and decision making. The Handbook of

Social Psychology, eds Gilbert DT, Fiske ST (McGraw-Hill, New York), 5th Ed, pp

542588.

3. Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk.

Econometrica 47:263291.

4. Levin IP, Gaeth GJ (1988) Framing of attribute information before and after con-

suming the product. J Consum Res 15:374378.

5. Shar E (1993) Choosing versus rejecting: Why some options are both better and

worse than others. Mem Cognit 21:546556.

6. Slovic P, Lichtenstein S (1983) Preference reversals: A broader perspective. Am Econ

Rev 73:596605.

7. Barr MS, Mullainathan S, Shar E (2009) The case for behaviorally informed regula-

tion. New Perspectives on Regulation, eds Moss D, Cisternino J (The Tobin Project,

Cambridge, MA), pp 2562.

8. Camerer C, Issacharoff S, Loewenstein G, ODonoghue T, Rabin M (2003) Regulation

for conservatives: Behavioral economics and the case for asymmetric paternalism.

Univ PA Law Rev 151:12111254.

9. Ubel PA (2009) Free Market Madness: Why Human Nature Is at Odds with Economics

and Why It Matters (Harvard Business, Boston).

10. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and

Happiness (Yale Univ Press, New Haven, CT).

11. Johnson EJ, Goldstein D (2003) Medicine. Do defaults save lives? Science 302:13381339.

12. McKenzie CRM, Liersch MJ, Finkelstein SR (2006) Recommendations implicit in policy

defaults. Psychol Sci 17:414420.

13. Grifn DW, Ross L (1991) Subjective construal, social inference, and human mis-

understanding. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed Zanna M (Academic,

New York), Vol 24, pp 319356.

14. Asch SE (1948) The doctrine of suggestion, prestige and imitation in social psychology.

Psychol Rev 55:250276.

15. Asch SE (1952) Social Psychology (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ).

16. Asch SE (1940) Studies in the principles of judgments and attitudes: II. Determination

of judgments by group and ego standards. J Soc Psychol 12:433465.

17. Cialdini RB (2001) Inuence: Science and Practice (Allyn & Bacon, Boston).

18. Cialdini RB, et al. (2006) Managingsocial norms for persuasive impact. Soc Inuence 1:315.

19. Prentice DA, Miller DT (1993) Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some

consequences of misperceiving the social norm. J Pers Soc Psychol 64:243256.

20. Larimer ME, Neighbors C (2003) The impact of social norms on gambling behavior

among college student. Psychol Addict Behav 17:235243.

21. Gneezy U, Rustichini A (2000) A ne is a price. J Legal Stud 29:117.

Davidai et al. PNAS | September 18, 2012 | vol. 109 | no. 38 | 15205

S

O

C

I

A

L

S

C

I

E

N

C

E

S

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Inequalities in Underserved Communities- a Public Health Perspective and in Covid19: Impact of Bad Public Policy on Certain PopulationDe la EverandInequalities in Underserved Communities- a Public Health Perspective and in Covid19: Impact of Bad Public Policy on Certain PopulationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bursztyn 2020Document27 paginiBursztyn 2020SalnangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Framing Democracy: A Behavioral Approach to Democratic TheoryDe la EverandFraming Democracy: A Behavioral Approach to Democratic TheoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (1)

- Bursztyn Egorov Fiorin Extreme Mainstream 2019-06-05Document74 paginiBursztyn Egorov Fiorin Extreme Mainstream 2019-06-05dadacestmoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review: Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein: A manifesto of libertarian paternalismDe la EverandBook Review: Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein: A manifesto of libertarian paternalismÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ideological Innocence - AhlerDocument60 paginiIdeological Innocence - AhlerJoelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re-Thinking Green: Alternatives to Environmental BureaucracyDe la EverandRe-Thinking Green: Alternatives to Environmental BureaucracyEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (4)

- P P: I E, V, L G: Ower and Olitics Nsights From An XIT Oice AND Oyalty AMEDocument46 paginiP P: I E, V, L G: Ower and Olitics Nsights From An XIT Oice AND Oyalty AMEstrongmarathon8157Încă nu există evaluări

- Raming Heory: Dennis Chong and James N. DruckmanDocument26 paginiRaming Heory: Dennis Chong and James N. DruckmanKevin BenoitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re-Assessing Elite-Public Gaps in Political Behavior: Joshua D. KertzerDocument15 paginiRe-Assessing Elite-Public Gaps in Political Behavior: Joshua D. KertzerJhobel TasicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Perspectives On Electoral BehaviorDocument11 paginiOxford Handbooks Online: Perspectives On Electoral BehaviorAmado Rene Tames GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- UC Berkeley Previously Published WorksDocument21 paginiUC Berkeley Previously Published WorksNorbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Report DraftDocument10 paginiResearch Report Draftapi-386746776Încă nu există evaluări

- Social Preferences and Political ParticipationDocument13 paginiSocial Preferences and Political ParticipationNúcleo Artes Prácticas CulturalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing The Effects of DefaultsDocument6 paginiComparing The Effects of DefaultsJuan SebastiánÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clark GolderDocument46 paginiClark GolderNikeBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: The Self-And Other-Interest InventoryDocument21 paginiJournal of Personality and Social Psychology: The Self-And Other-Interest InventoryCatarina C.Încă nu există evaluări

- PNAS 2010 Pronin 22469 74Document6 paginiPNAS 2010 Pronin 22469 74Vlad PredaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article Paper PDFDocument14 paginiArticle Paper PDFMutembeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fitzgerald What Is Political Jo PB 2013Document28 paginiFitzgerald What Is Political Jo PB 2013Josh Walter StrongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology, Behavioral Economics, and Public PolicyDocument15 paginiPsychology, Behavioral Economics, and Public Policyneda_647541968Încă nu există evaluări

- Wayne Carly Rationalizing ConflictDocument30 paginiWayne Carly Rationalizing ConflictAlejandroHdzLuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final PaperDocument6 paginiFinal Paperapi-726978159Încă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Dissonance TheoryDocument12 paginiCognitive Dissonance TheoryLijngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black-Box Models of Candidate EvaluationDocument15 paginiBlack-Box Models of Candidate EvaluationJoel CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judicial Politics and Social Rights - Langford PaperDocument39 paginiJudicial Politics and Social Rights - Langford PaperYohana CardenasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jacoby, Value ChoicesDocument18 paginiJacoby, Value ChoicesDiego VergaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experimental Research On Democracy ExampleDocument31 paginiExperimental Research On Democracy ExamplekonkatelebeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pol 1015 NotesDocument39 paginiPol 1015 NotesAlfred Chalwe100% (1)

- Assigment Foreign Policy Decision MakingDocument10 paginiAssigment Foreign Policy Decision MakingAynaa Eis100% (1)

- The Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceDocument66 paginiThe Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceRó StroskoskovichÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceDocument18 paginiThe Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceFermilyn AdaisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heuristics in Judgment and Decision-MakingDocument10 paginiHeuristics in Judgment and Decision-MakingHomo CyberneticusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cass Sunstein - UlmannDocument37 paginiCass Sunstein - UlmannKrishina RibeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dahlberg & Holmberg - Understanding Satisfaction With The Way Democracy Works - Democracy Versus BureaucracyDocument30 paginiDahlberg & Holmberg - Understanding Satisfaction With The Way Democracy Works - Democracy Versus BureaucracyMudre MislicomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Political BehaviorDocument35 paginiSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Political BehaviorBob BoatÎncă nu există evaluări

- China 'S Ideological Spectrum: Jennifer Pan, Stanford University Yiqing Xu, University of California, San DiegoDocument20 paginiChina 'S Ideological Spectrum: Jennifer Pan, Stanford University Yiqing Xu, University of California, San DiegoAngelo-Daniel SeraphÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annurev Polisci 10 072805 103054Document24 paginiAnnurev Polisci 10 072805 103054ElpriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hoff (2011), 'Tastes, Castes, and Culture'Document26 paginiHoff (2011), 'Tastes, Castes, and Culture'Joe OgleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jones N Harris 1967Document24 paginiJones N Harris 1967Mirela StanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach: Research ArticlesDocument21 paginiConceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach: Research ArticlesJoel CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gilens and Page 2014-Testing Theories 3-7-14Document42 paginiGilens and Page 2014-Testing Theories 3-7-14gugamachalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaller Feldman - A Simple Theory of Survey ResponseDocument39 paginiZaller Feldman - A Simple Theory of Survey ResponseAna-Maria Elena CostinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prisoner Reentry, Employment, Signaling, and The Better Identification of DesistersDocument11 paginiPrisoner Reentry, Employment, Signaling, and The Better Identification of DesistersAstrokibuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jervis Preception MispreceptionDocument15 paginiJervis Preception MispreceptionLolo SilvanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beyond The Self: Social Identity, Altruism, and Political ParticipationDocument15 paginiBeyond The Self: Social Identity, Altruism, and Political ParticipationLeon AshleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anzia SeniorTurnout 7 1 17Document36 paginiAnzia SeniorTurnout 7 1 17Tashfia Mubtasim PropaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Example Paper Used in The Overview Presentations-2Document37 paginiExample Paper Used in The Overview Presentations-2Fred OkelloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Attribution (Psychology) : Theories and ModelsDocument8 paginiAttribution (Psychology) : Theories and ModelsRavneet Kaur MaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Measuring Voter DecisionDocument26 paginiMeasuring Voter DecisionAndreea DobritaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2002 Bias Blind SpotDocument13 pagini2002 Bias Blind Spotraluca.bodea6328Încă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Dissonance TheoryDocument44 paginiCognitive Dissonance TheoryAde P IrawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disability, Perceived Discrimination and Political ParticipationDocument27 paginiDisability, Perceived Discrimination and Political ParticipationGustavo Martins PiccoloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inequality and Democratic Responsiveness: Who Gets What They Want From Government?Document41 paginiInequality and Democratic Responsiveness: Who Gets What They Want From Government?Andrei GabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Where Is Presidential Power Measuring Presidential Discretion Using ExpertsDocument15 paginiWhere Is Presidential Power Measuring Presidential Discretion Using ExpertsCamila Almeida PorfiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ross & Ward - Naive RealismDocument17 paginiRoss & Ward - Naive RealismAlex EpaminondasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Universidad NebraskaDocument6 paginiUniversidad NebraskaPablo Navas ArroyoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voters Rationalization StudyDocument74 paginiVoters Rationalization StudyoffegoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Research On Sexual Abuse PDFDocument22 paginiQuantitative Research On Sexual Abuse PDFDivine GraceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why The Giant Sleeps So Deeply - Political Consequences of Individual-Level Latino DemographicsDocument23 paginiWhy The Giant Sleeps So Deeply - Political Consequences of Individual-Level Latino DemographicsTyler SmithÎncă nu există evaluări