Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

9 Pajuyo Vs Ca

Încărcat de

Hector Mayel Macapagal0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

42 vizualizări3 paginicredit

Titlu original

9 pajuyo vs ca

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentcredit

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

42 vizualizări3 pagini9 Pajuyo Vs Ca

Încărcat de

Hector Mayel Macapagalcredit

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 3

COLITO T. PAJUYO, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and EDDIE GUEVARRA, respondents.

[G.R. No. 146364, June 3, 2004, Carpio, J.]

Topic: Commodatum

Doctrine: In a contract for commodatum, one of the parties delivers to another something not so consumable so

that the latter may use the same for a certain time and return it. An essential feature of commodatum is that it is

gratuitous. Another feature of commodatum is that the use of the thing belonging to another is for a certain

period. Thus, the bailor cannot demand the return of the thing loaned until after expiration of the of the period

stipulated or after the accomplishment of the use for which commodatum is constituted. If the bailor should have

urgent need of the thing, he may demand its return for temporary use. If the use of the thing is merely tolerated

by the bailor, he can demand the return of the thing at will, in which case the contract relation is called the a

precarium. Under the Civil Code, precarium is a kind of commodatum.

Nature: Petition for review

Facts:

1. Petitioner Colito T. Pajuyo (Pajuyo) paid P400 to a certain Pedro Perez for the rights over a 250-

square meter lot in Barrio Payatas, QC. Pajuyo then constructed a house made of light materials on the

lot. Pajuyo and his family lived in the house from 1979 to 1985.

2. In 1985, Pajuyo and private respondent Eddie Guevarra (Guevarra) executed a Kasunduan or

agreement.

> Pajuyo, as owner of the house, allowed Guevarra to live in the house for free provided Guevarra would

maintain the cleanliness and orderliness of the house. Guevarra promised that he would voluntarily

vacate the premises on Pajuyos demand.

3. In 1994, Pajuyo informed Guevarra of his need of the house and demanded that Guevarra vacate the

house.

> Guevarra refused.

4. Pajuyo filed an ejectment case against Guevarra with the MTC of QC

> In his Answer, Guevarra claimed that:

a) Pajuyo had no valid title or right of possession over the lot where the house stands because the lot is within

the 150 hectares set aside by Proclamation No. 137 for socialized housing.

b) from December 1985 to September 1994, Pajuyo did not show up or communicate with him

c) neither he nor Pajuyo has valid title to the lot

> the MTC rendered its decision in favor of Pajuyo, ordering Guevarra to:

a) vacate the house and lot or have anyone claiming a right under him to vacate it.

b) pay Pajuyo 300php/month from last demand for the use of the premises

c) pay attoneys fees + cost of the suit

> the subject of the agreement between Pajuyo and Guevarra is the house and not the lot. Pajuyo is the owner

of the house, and he allowed Guevarra to use the house only by tolerance. Thus, Guevarras refusal to vacate the

house on Pajuyos demand made Guevarras continued possession of the house illegal.

5. Guevarra appealed to the RTC.

> the RTC affirmed the MTC decision

> The RTC upheld the Kasunduan, which established the landlord and tenant relationship between Pajuyo and

Guevarra, and so the terms of the Kasunduan bound Guevarra to return possession of the house on demand.

> The RTC rejected Guevarras claim of a better right under Proclamation No. 137, the Revised National

Government Center Housing Project Code of Policies and other pertinent laws.

> In an ejectment suit, the RTC has no power to decide Guevarras rights under these laws because in an

ejectment case, the only issue for resolution is material or physical possession, not ownership.

> both MTC and RTC: the Kasunduan between Pajuyo and Guevarra created a legal tie akin to that of a landlord

and tenant relationship.

6. Guevarra received the RTC decision on 29 November 1996. Guevarra had only until 14 December 1996 to file

his appeal with the CA. Instead of filing his appeal with the CA, Guevarra filed with the Supreme Court a Motion

for Extension of Time to File Appeal by Certiorari Based on Rule 42 (motion for extension).

> Guevarra theorized that his appeal raised pure questions of law.

> The Receiving Clerk of the SC received the motion for extension on 13 December 1996 or one day before the

right to appeal expired.

> this allowed Guevarra to file his petition for review with the SC

7. The SC issued a Resolution referring the motion for extension to the CA which has concurrent jurisdiction over

the case because the case presented no special and important matter for the SC to take cognizance of at the first

instance.

8. The CA issued a Resolution granting the motion for extension conditioned on the timeliness of the filing of the

motion.

> ordered Pajuyo to comment on Guevarras petition for review.

> the CA reversed the RTC decision

> Pajuyo and Guevarra are squatters. Pajuyo and Guevarra illegally occupied the contested lot which the

government owned. Perez, the person from whom Pajuyo acquired his rights, was also a squatter. Perez had no

right or title over the lot because it is public land. The assignment of rights between Perez and Pajuyo, and the

Kasunduan between Pajuyo and Guevarra, did not have any legal effect. Pajuyo and Guevarra are in pari delicto

or in equal fault. The court will leave them where they are.

> the Kasunduan is not a lease contract but a commodatum because the agreement is not for a price certain.

> since Pajuyo admitted that he resurfaced only in 1994 to claim the property, Guevarra has a better right over

the property under Proclamation No. 137 issued on 7 September 1987. At that time, Guevarra was in physical

possession of the property, giving him first priority as beneficiary under the project.

9. Pajuyo filed an MR. Pajuyo pointed out:

a) that the CA should have dismissed outright Guevarras petition for review because it was filed out of time

b) it was Guevarras counsel and not Guevarra who signed the certification against forum-shopping

> CA denied the MR for lack of merit

> In denying Pajuyos MR, the appellate court debunked Pajuyos claim that Guevarra filed his motion for

extension beyond the period to appeal, stating that he filed the motion one day before the expiration of the

reglementary period on 14 December 1996. Thus, the motion for extension was deemed to have properly

complied with the condition imposed by the CA to grant the 30-day extension to file the petition for review.

> the CA also pointed out that Pajuyo did not raise the issue about Guevarras counsel having signed the

certificate of forum shopping in his Comment and so Pajuyo could not now seek the dismissal of the case after he

had extensively argued on the merits of the case. This technicality, the appellate court opined, was clearly an

afterthought.

Issue:

Whether the Kasunduan voluntarily entered into by the parties was in fact a commodatum, instead of a Contract

of Lease as found by the MTC.

Held:

Pajuyo is Entitled to Physical Possession of the Disputed Property

The Kasunduan reads:

Ako, si COL[I]TO PAJUYO, may-ari ng bahay at lote sa Bo. Payatas, Quezon

City, ay nagbibigay pahintulot kay G. Eddie Guevarra, na pansamantalang

manirahan sa nasabing bahay at lote ng walang bayad. Kaugnay nito, kailangang

panatilihin nila ang kalinisan at kaayusan ng bahay at lote.

Sa sandaling kailangan na namin ang bahay at lote, silay kusang aalis ng

walang reklamo.

Based on the Kasunduan, Pajuyo permitted Guevarra to reside in the house and lot free of rent,

but Guevarra was under obligation to maintain the premises in good condition. Guevarra promised to

vacate the premises on Pajuyos demand but Guevarra broke his promise and refused to heed Pajuyos

demand to vacate.

Where the plaintiff allows the defendant to use his property by tolerance without any contract, the

defendant is necessarily bound by an implied promise that he will vacate on demand, failing which, an action for

unlawful detainer will lie. The defendants refusal to comply with the demand makes his continued possession of

the property unlawful. The status of the defendant in such a case is similar to that of a lessee or tenant whose

term of lease has expired but whose occupancy continues by tolerance of the owner.

This principle should apply with greater force in cases where a contract embodies the permission or

tolerance to use the property. The Kasunduan expressly articulated Pajuyos forbearance. Pajuyo did not

require Guevarra to pay any rent but only to maintain the house and lot in good condition. Guevarra

expressly vowed in the Kasunduan that he would vacate the property on demand. Guevarras refusal to

comply with Pajuyos demand to vacate made Guevarras continued possession of the property unlawful.

We do not subscribe to the Court of Appeals theory that the Kasunduan is one of commodatum.

In a contract of commodatum, one of the parties delivers to another something not consumable

so that the latter may use the same for a certain time and return it. An essential feature of commodatum

is that it is gratuitous. Another feature of commodatum is that the use of the thing belonging to another is

for a certain period. Thus, the bailor cannot demand the return of the thing loaned until after expiration of

the period stipulated, or after accomplishment of the use for which the commodatum is constituted. If the

bailor should have urgent need of the thing, he may demand its return for temporary use. If the use of the

thing is merely tolerated by the bailor, he can demand the return of the thing at will, in which case the

contractual relation is called a precarium. Under the Civil Code, precarium is a kind of commodatum.

The Kasunduan reveals that the accommodation accorded by Pajuyo to Guevarra was not

essentially gratuitous. While the Kasunduan did not require Guevarra to pay rent, it obligated him to

maintain the property in good condition. The imposition of this obligation makes the Kasunduan a

contract different from a commodatum. The effects of the Kasunduan are also different from that of a

commodatum. Case law on ejectment has treated relationship based on tolerance as one that is akin to a

landlord-tenant relationship where the withdrawal of permission would result in the termination of the

lease. The tenants withholding of the property would then be unlawful.

Even assuming that the relationship between Pajuyo and Guevarra is one of commodatum,

Guevarra as bailee would still have the duty to turn over possession of the property to Pajuyo, the bailor.

The obligation to deliver or to return the thing received attaches to contracts for safekeeping, or contracts

of commission, administration and commodatum. These contracts certainly involve the obligation to

deliver or return the thing received.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Conflict WaiverDocument2 paginiConflict WaiverjlurosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crawler Base DX500/DX600/DX680/ DX700/DX780/DX800: Original InstructionsDocument46 paginiCrawler Base DX500/DX600/DX680/ DX700/DX780/DX800: Original InstructionsdefiunikasungtiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biaco vs. Countryside Rural BankDocument2 paginiBiaco vs. Countryside Rural BankHector Mayel Macapagal100% (1)

- Republic Vs RoxasDocument4 paginiRepublic Vs RoxasHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chavez Vs CADocument2 paginiChavez Vs CAHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- De La Cruz V Asian ConsumerDocument3 paginiDe La Cruz V Asian ConsumerHector Mayel Macapagal100% (1)

- Pentacapital V MahinayDocument3 paginiPentacapital V MahinayHector Mayel Macapagal0% (1)

- PNB V Phil. Vegetable OilDocument2 paginiPNB V Phil. Vegetable OilHector Mayel Macapagal33% (3)

- Law Favoreth Diligence, and Therefore, Hateth Folly and Negligence.-Wingate's MaximDocument3 paginiLaw Favoreth Diligence, and Therefore, Hateth Folly and Negligence.-Wingate's MaximHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8 BPI Investment Vs Court of Appeals GR 133632Document2 pagini8 BPI Investment Vs Court of Appeals GR 133632Hector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Locsin vs. MekeniDocument4 paginiLocsin vs. MekeniHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Miguel V MontanezDocument4 paginiMiguel V MontanezHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Locsin vs. MekeniDocument4 paginiLocsin vs. MekeniHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Saura Import & Export Vs DBPDocument2 pagini4 Saura Import & Export Vs DBPHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Republic Vs GrijaldoDocument3 pagini3 Republic Vs GrijaldoHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guingona Vs City of ManilaDocument9 paginiGuingona Vs City of ManilaHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calalas Vs CA - TranspoDocument5 paginiCalalas Vs CA - TranspoHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chas Realty Vs TalaveraDocument3 paginiChas Realty Vs TalaveraHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ferrer Vs RabacaDocument2 paginiFerrer Vs RabacaHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bustamante Vs Rosel CreditDocument2 paginiBustamante Vs Rosel CreditHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inciong Vs CA - CDDocument2 paginiInciong Vs CA - CDHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bustamante Vs RoselDocument2 paginiBustamante Vs RoselHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Republic Vs Grijaldo (Short)Document2 pagini3 Republic Vs Grijaldo (Short)Hector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- UPSU Vs LaguesmaDocument1 paginăUPSU Vs LaguesmaHector Mayel MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Methods of Teaching Syllabus - FinalDocument6 paginiMethods of Teaching Syllabus - FinalVanessa L. VinluanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Algorithm - WikipediaDocument34 paginiAlgorithm - WikipediaGilbertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethercombing Independent Security EvaluatorsDocument12 paginiEthercombing Independent Security EvaluatorsangelÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECO 101 Assignment - Introduction To EconomicsDocument5 paginiECO 101 Assignment - Introduction To EconomicsTabitha WatsaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- CNG Fabrication Certificate16217Document1 paginăCNG Fabrication Certificate16217pune2019officeÎncă nu există evaluări

- IOSA Information BrochureDocument14 paginiIOSA Information BrochureHavva SahınÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCS Valve: Minimizes Body Washout Problems and Provides Reliable Low-Pressure SealingDocument4 paginiMCS Valve: Minimizes Body Washout Problems and Provides Reliable Low-Pressure SealingTerry SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBOPS601 Develop Implement Business Plans - SDocument91 paginiBSBOPS601 Develop Implement Business Plans - SSudha BarahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Te 1569 Web PDFDocument272 paginiTe 1569 Web PDFdavid19890109Încă nu există evaluări

- We Move You. With Passion.: YachtDocument27 paginiWe Move You. With Passion.: YachthatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner's Response To Show CauseDocument95 paginiPetitioner's Response To Show CauseNeil GillespieÎncă nu există evaluări

- OrganometallicsDocument53 paginiOrganometallicsSaman KadambÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Proposal IntroductionDocument8 paginiResearch Proposal IntroductionIsaac OmwengaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1980WB58Document167 pagini1980WB58AKSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 11 Accountancy NCERT Textbook Chapter 4 Recording of Transactions-IIDocument66 paginiClass 11 Accountancy NCERT Textbook Chapter 4 Recording of Transactions-IIPathan KausarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tate Modern London, Pay Congestion ChargeDocument6 paginiTate Modern London, Pay Congestion ChargeCongestionChargeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intelligent Smoke & Heat Detectors: Open, Digital Protocol Addressed by The Patented XPERT Card Electronics Free BaseDocument4 paginiIntelligent Smoke & Heat Detectors: Open, Digital Protocol Addressed by The Patented XPERT Card Electronics Free BaseBabali MedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Donation Drive List of Donations and BlocksDocument3 paginiDonation Drive List of Donations and BlocksElijah PunzalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1Document11 paginiLecture 1Taniah Mahmuda Tinni100% (1)

- PPB 3193 Operation Management - Group 10Document11 paginiPPB 3193 Operation Management - Group 10树荫世界Încă nu există evaluări

- Application of ARIMAX ModelDocument5 paginiApplication of ARIMAX ModelAgus Setiansyah Idris ShalehÎncă nu există evaluări

- CavinKare Karthika ShampooDocument2 paginiCavinKare Karthika Shampoo20BCO602 ABINAYA MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fr-E700 Instruction Manual (Basic)Document155 paginiFr-E700 Instruction Manual (Basic)DeTiEnamoradoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beam Deflection by Double Integration MethodDocument21 paginiBeam Deflection by Double Integration MethodDanielle Ruthie GalitÎncă nu există evaluări

- AkDocument7 paginiAkDavid BakcyumÎncă nu există evaluări

- tdr100 - DeviceDocument4 paginitdr100 - DeviceSrđan PavićÎncă nu există evaluări

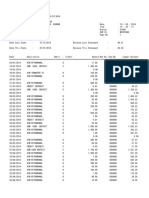

- Bank Statement SampleDocument6 paginiBank Statement SampleRovern Keith Oro CuencaÎncă nu există evaluări