Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Lecture 2

Încărcat de

Ancuta AngelicaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Lecture 2

Încărcat de

Ancuta AngelicaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem.

I, 2014

1

2.5. Clauses

2.5.1. Finite and non-finite clauses

At the level of clause, English grammar distinguishes between finite clauses (with the verbal

realized by a finite verb

1

) and non-finite clauses (with the verbal realized by a non-finite verb

2

).

This is due to the fact that, because the central element of a clause is the verb phrase, the clause

is finite or non-finite depending on the form of its verbal.

Consider the clauses in bold in the following examples:

1. |||I expected ||that he would help me.|| |||

2. |||I expected ||him to help me.|| |||

3. |||I expected ||to get help.|| |||

All three example sentences contain an embedded object clause in bold. The first (that he would

help me) is finite, while in both 2 (him to help me) and 3 (to get help) the embedded clause is

non-finite. The difference between the two embedded clauses is that if in 2 the subject is

lexically realized by a NP (him), in 3 the subject position is not lexically filled.

Because English has case distinctions only for pronouns, another rule concerns the nominal

element preceding the verb: the 3

rd

person pronoun is typically (but not exclusively) in the

nominative in the finite clause and in the accusative or possessive in the non-finite clause.

If a participle, a gerund or an infinitive is the first or only verb in the verb phrase, the VP is non-

finite. A non-finite verb form

3

functions both as a verb and as another word class.

non-finite verb form example word class grammatical

behaviour

present participle The snoring dog disturbed Toms reading. adjective

present participle Mumbling, he went on reading. adverb

past participle He was reading the damaged manuscript. adjective

past participle Exasperated, he resumed his reading. adverb

gerund He likes reading. noun

to-infinitive He likes to read. noun

to-infinitive He has a manuscript to read. adjective

bare infinitive He made them come, too. verb

In Strumpf and Douglass view, because participles, gerunds and infinitives are verb forms

(called by them verbals,), they

retain some of the abilities of verbs. They can carry objects or take modifiers and

complements. At the same time, verbals possess abilities unknown to the typical verb,

the abilities of other parts of speech. In this way, verbals may perform the duties of

1

Finite and non-finite verbs are discussed further in 4.4.

2

Some grammarians classify non-finite clauses as participial, gerund and infinitive phrases but, because in the

approach of this course, any verb phrase consists exclusively of verb words, only certain one-word (with no

modifiers or complements) participial, gerund and infinitive constructions are recognized as phrases.

3

Some grammarians call participles, gerunds and infinitives verbals, but this course recognizes the verbal as the

syntactic function realized exclusively by a verb phrase (see 2.2.2. and 3.3.1.).

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

2

two parts of speech simultaneously. (The Grammar Bible: Everything You Always

Wanted to Know about Grammar But Didn't Know Whom to Ask , 2004, p. 136)

In English, there are three types of non-finite clauses, depending on the form of the first verb in

the verb phrase:

1. -ing clauses

a. -ing participle clauses

Doug Crandell lives in Douglasville, Georgia, where his wife has crocheted him nine winter hats

while watching The Andy Griffith Show. (The Sun Magazine)

b. ing gerund clauses

Wed not eaten at many fast-food restaurants, and seeing our mother in her uniform made me

feel as if wed somehow been promoted from farm family to suburbanites. (The Sun Magazine)

2. -ed clauses/-ed participle clauses

I spotted our mother standing proudly on the front porch, dressed in her new work outfit. (The

Sun Magazine)

3. infinitive clauses

(a) with to

You couldnt have been expected to know that. (The Sun Magazine)

(b) without to

The book helped reshape Americans attitudes toward this native predator []. (The Sun

Magazine)

Such non-finite clauses may be regarded as reduced clauses which often lack a subject but which

can be analysed in terms of constituents/ elements of the clause. Most types can be expanded into

finite clauses.

non-finite clause constituents expanded finite clause

1. while watching The Andy Griffith Show V + O while she was watching The Andy Griffith

Show

2. seeing our mother in her uniform V + O + A that I saw our mother in her uniform

3. dressed in her new work outfit. V + A she was dressed in her new work outfit.

4. to know that. V + O that you know that

5. reshape Americans attitudes toward this native

predator

V + O that Americans attitudes toward this native

predator are reshaped

In headlines, auxiliary verbs are usually dropped from progressive and passive structures, leaving

only present/past participles. Headlines are often expanded in the article body, as in the example

below.

headline body

Great Barrier Reef damage irreversible

unless radical action taken

The Great Barrier Reef will suffer irreversible damage by 2030

unless radical action is taken to lower carbon emissions, a stark

new report has warned. (The Guardian)

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

3

In relation to the auxiliaries and voice of non-finite clauses, Huddleston and Pullum (The

Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, 2002, p. 1174) note that modal auxiliaries and

operator do are excluded, but each of the three varieties (-ing clauses, -ed clauses and infinitive

clauses) admits one or more of the remaining three auxiliaries:

1. -ing clauses (which the authors call gerund-participials) accept have and passive be, but

not progressive be.

perfect have I regret having told them.

passive be I resent being given so little notice.

progressive be I remember being working when they arrived.

2. . -ed clauses accept progressive and passive be.

passive be Ed has been seen.

progressive be Ed has been seeing her.

3. infinitive clauses accept all the three auxiliaries.

perfect have I expect to have finished soon.

passive be I expect to be working all weekend.

progressive be I expect to be interviewed by the police.

Unlike in most finite clauses, the presence of the subject is not obligatory in non-finite clauses.

Huddleston and Pullum consider the subject an optional element in non-finite clauses, not an

element whose presence is necessary for an expression to qualify as a clause (2002, p. 1175).

When present, the subject makes it clear that the non-finite verbal does not have the same subject

as the finite verbal of the main clause. A characteristic of the subjects of non-finite verbals is that

normally they are not nominative. This feature becomes obvious in subjects realized by personal

pronouns, which are either accusative or genitive.

subjectless clause clause containing a subject

-ing clause a. Having agreed on all the details, we then rapidly

proceeded with the preparation of draft contracts.

b. Many teachers enjoy telling jokes in class.

a. He and I having agreed on all the details, the

preparation of draft contracts then proceeded rapidly.

b. Many teachers enjoy students

4

telling jokes in class.

-ed clauses Having been exposed, the thief turned to flee. His identity having been exposed, the thief turned to

flee

infinitive

clause

a. I want to stop listening to this rigmarole.

b. I will be happy to do the homework.

a. I want you to stop listening to this rigmarole.

b. I will be happy for my students to do

5

the homework.

Huddleston and Pullum distinguish between clauses that consist only of the VP functioning as

verbal, on the one hand (Having been exposed, the thief turned to flee.), and attributive VPs

6

4

The subject of a gerund must be in the possessive form, since gerunds behave like nouns and should then be

preceded by the possessive forms of nouns/pronouns (they mean whose + noun). However, in colloquial speech

the objective form is very common.

5

The for +accusative + to-infinitive structure is common after adjectives expressing wishes and personal feelings. It

is not possible after likely and probable.

6

Participial adjective is a traditional term for an adjective that has the same form as the present or past participle of

a verb, but functions as a descriptive adjective and usually exhibits its ordinary properties of a central adjective

(they have the ability to occur both attributively and predicatively, are gradable and have comparative and

superlative forms). The adjectives in this class are also called verbal adjectives or deverbal adjectives.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

4

functioning as modifiers of nouns in NPs, on the other (our rapidly approaching deadline, a

poorly drafted report).

Whenever the non-finite forms function as the verbals of clauses which also contain subjects in

the nominative, different from the subject of the main clause, they form absolute verbal

constructions. An absolute construction acts as a modifier, but it is not modifying any particular

part of the main clause/sentence; instead, it modifies the entire clause/sentence by adding

information to it. In the example below, the non-finite clause is underlined, the verbal is in bold

and the subject is double-underlined.

All things considered, I think Putin is the right man for Russia, especially in these interesting

times. (The Guardian)

The discussion of the absolute constructions is continued in 5.6.2.

a. Participial clauses (1.a and 2 above) are non-finite clauses consisting of a participle

accompanied or not by the noun phrase/phrases that function as the subject, direct object/objects,

indirect object/objects, or complement/complements of the participle verb (see examples 1 and 3

in the table above).

In English there are two participle forms:

present participle (base form + -ing).

past participle (for all regular verbs, the past participle form ends in ed, while irregular

verbs endings vary considerably (for instance, been, brought, seen, etc.).

Both of them can function as the verbals of non-finite clauses.

example participle form syntactic

function

clause type

Because if F1 teams are paying 800

for a wheel nut, then whoever they

are getting them from must have

seen them coming. (The Guardian)

present participle object SV (acc, + present participle). The verbal in the main

clause (double underlined) that governs the participle

is a perception/cognition

7

or causative

8

verb.

Michael Jackson as you've never

seen him painted before. (The

Guardian)

past participle object SVA (acc. + past participle).

The verbal in the main clause (double underlined)

that governs the participle is a perception/cognition

or causative verb.

Robert Spencer came across picture

of his injured stepson while reading

reports on the Santiago de

Compostela crash. (The Guardian)

present participle adverbial (conj.) VO

Just like full adverbial clauses, only more

economically, participial clauses express

condition, reason, cause, result or time. They can

be introduced by subordinating conjunctions such

as if, unless, because, when, while, etc. The

participle clause normally comes in front of the

main clause

US ambassador says Iraqi aides will

quit unless granted asylum (The

Guardian)

past participle adverbial

7

Examples of perception/cognition verbs include see, hear, feel, know, believe, think, remember, recall, forget, etc.

8

Causative verbs are used to indicate that some person or thing helps to make something happen and are followed

by another verb form. Examples include cause, allow, help, have, enable, keep, hold, let, force, require, and

make.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

5

The meeting ending earlier than

expected, everyone gathered their

belongings and left.

present participle clause/

sentence

modifier

SVA

These clauses are called absolute participial

clauses because they are not dependent on any

other part of the main clause, though they cannot

be used independently, as they lack a finite verbal.

The meeting ended, everyone

gathered their belongings and left.

past participle clause/

sentence

modifier

One-word participle phrases usually occur as premodifiers (the crying baby), but they may,

however, occur at the beginning of a sentence as adjuncts (Troubled, he went to) or inside

the sentence, as parenthetical elements (His gaze, frozen, moved away from ).

Negative participle clauses are also possible, with not normally placed before the participle.

Not having time to finish my essay on time, I decided to withdraw from the contest.

Clearly not entirely convinced, he took another look at the photos.

b. Gerund clauses (1.b above) are non-finite clauses consisting of a gerund accompanied or not

by the noun phrase/phrases that function as the subject, direct object/objects, indirect

object/objects, or complement/ complements of the gerund verb (see example 2 in the table

above).

c. Infinitive clauses (3.a and 3.b above) are non-finite clauses consisting of the infinitive or bare

infinitive form of a verb accompanied or not by the noun phrase/phrases that function as the

subject, direct object/objects, indirect object/objects, or complement/ complements of the

infinitive verb (see examples 4 and 5 in the table above).

Split infinitives occur when one or more words are interposed between the particle to and the

verb (to quickly remove, to more clearly articulate, to more than double, to suddenly leave,

etc.), but they should be avoided in formal writing.

Present participle clauses vs. gerund clauses

Because present participles and gerunds are identical in form (-ing ending), it is sometimes

difficult to distinguish between them. However, the difference becomes obvious in contexts,

since participles function as adjectives pre- or postmodifying a noun, while gerunds function as

nouns. In the examples below, the participial clause and the gerund clauses are in bold.

Mary, constantly nagging, drives him mad.

Marys constant nagging drives him mad.

In the first, constantly nagging is a participle which functions as an AdjP whose head is nagging,

which modifies Mary and which can be expanded into a relative clause (who is constantly

nagging).

In the second, Marys constant nagging functions as a NP whose head is nagging and which

realizes the syntactic function of subject. In the gerund clause in this sentence, the subject

(Marys) of the non-finite verbal (nagging) is present.

As a rule, when the subject of the gerund occurs in the gerund clause, it is usually in the

possessive case (morphologically marked on pronouns and common or proper nouns -

Her/the womans/Marys constant nagging ). This does not normally happen with

compound subjects (Mary and her mother constant nagging ). However, when the

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

6

gerund expresses general activities (driving, teaching, diving), its subject will be elided

(Driving can be tiresome).

Gerunds vs. infinitives

Gerunds and infinitives are different in form but, because both function as nominals, usage

confusion may often arise especially for non-native speakers of English.

Confusion between gerunds and infinitives occurs primarily in cases in which one or the

other functions as the direct object in a sentence. In English some verbs take gerunds as

verbal direct objects exclusively while other verbs take only infinitives and still others

can take either. (Owl)

The examples below show one verb (agree) that can take only the infinitive as direct object and

another one that takes only gerunds.

Abbott and Obama agree to extend Australia's defence cooperation with US (The Guardian)

Abbott and Obama agree extending Australia's defence cooperation with US

PRISM scandal: tech giants flatly deny allowing NSA direct access to servers (The Guardian)

PRISM scandal: tech giants flatly deny to allow NSA direct access to servers

The same source offers a list of such verbs, organized according to which kind of verbal direct

object they take.

Verbs that take only infinitives as verbal direct objects (Owl)

agree expect hope learn neglect pretend propose

attempt hesitate intend need plan promise want

decide

Verbs that take only gerunds as verbal direct objects (Owl)

admit delay finish give up postpone recommend

appreciate deny get/be

accustomed to

keep practice regret

avoid detest get/be tired of keep (on) put off risk

be fond

of

dislike get/be through mind quit suggest

can't help tolerate get/be used to miss recall stop (quit)

consider enjoy

Verbs that take gerunds or infinitives as verbal direct objects (Owl)

begin like remember

continue love start

hate prefer try

A few verbs can take both gerunds and infinitives but with a change in meaning.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

7

come

forget

go on

mean

regret

remember

stop

try

A discussion with examples can be found at www.edufind.com/

english/grammar/gerund_or_infinitive2.php.

Verbs that take an object plus a gerund or a bare infinitive

feel hear notice watch

see smell observe

The use of the gerund normally indicates a continuous action, and the use of the bare infinitive

indicates a one-time action.

In traditional Romanian grammar, only a finite verb can be the verbal of a clause, and, consequently,

finite moods are called predicative moods, while non-finite moods are called non-predicative moods.

Non-finite forms in Romanian

In Romanian there are four non-finite forms: participle, gerund, infinitive and supine. Except for the

supine, the others can be turned into nouns by the presence of the enclitic definite article, of the

proclitic indefinite article, of and adjective or a preposition. They can even appear in the vocative:

participle (cntat cntatul, citit cititul, condus condusul)

o Pe veci pierduto, vecinic adorato! (M. Eminescu, Sonet III)

gerund nominalization is uncommon and it occurs through its preliminary adjectivization:

gerund adjectiv noun (intrnd intrndul/un intrnd, suferind suferindul/un

suferind);

o Murindului sperana, turbrii rzbunarea,/Profetului blestemul, credinei

Dumnezeu (M. Eminescu, Amorul unei marmure)

long infinitive (a cnta cntare, a citi citire, a conduce conducere)

o Cu geana ta m-atinge pe pleoape,/S simt fiorii strngerii n bra.(M. Eminescu, Sonet

III)

2.5.2. Subordinate clauses

According to the VP used as verbal and to the presence or absence of a subordinator, there are

four types of subordinate clauses.

finite verb subordinator

main clause

9

+ -

A. subordinate clause + +

B. subordinate clause + -

C. subordinate clause - +

D. subordinate clause - -

9

For comparison, a main clause is also diagrammed in the table.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

8

o Notice: Category B is quite rare.

The following examples illustrate the four types of subordinate clauses described in the table.

A: ||when nobody was looking|| [+ finite verb], [+ subordinator]

B: ||| ||Had nobody looked,|| he would have taken the note.|||

[+ finite verb], [- subordinator]

C: ||while looking for her|| [- finite verb], [+ subordinator]

D: ||| ||Looking up,|| he realized his mistake.||| [- finite verb], [- subordinator]

The situation in Romanian is to some extent different, mainly because grammatical rules equal

the number of the clauses in a sentence with the number of the finite verbs with the function of

predicat. Thus, clauses of type A and B are the only possible categories, exactly because they

have finite verbs, while C and D will be identified as pri de propoziie that can be expanded

into clauses by replacing the non-finite verb form with a finite one.

C: while looking

for her

[-finite verb],

[+subordinator]

C: while he was

looking for her

[+finite verb],

[+subordinator]

cutnd-o [-finite verb],

[-subordinator]

n timp ce o cuta [+finite verb],

[+subordinator]

D: Looking up,

he realized....

[-finite verb],

[-subordinator]

D: When he

looked up, he

realized...

[+finite verb],

[+subordinator]

Ridicndu-i

privirea, i

ddu....

[-finite verb],

[-subordinator]

Cnd i ridic

privirea, i

ddu....

[+finite verb],

[+subordinator]

Actually, Romanian grammar recognizes the connection between the clause elements and their

corresponding clause types, as well as various procedures to contract finite clauses into non-

finite ones. The table below endeavours to illustrate these correspondences by adapting a number

of examples proposed by Bulgr (1995: 2005).

ROMANIAN

parte de propoziie subordonat

o subiect

Se tie pregtirea lui.

o subiectiv

Se tie c e bine pregtit.

o predicat

Adevrul este acesta.

o predicativ

Adevrul e c e bine pregtit.

o nume predicativ

Adevrul este acesta.

o

1)

o Atribut

Apreciem faptul acesta.

o atributiv

Apreciem faptul c e bine pregtit.

o complement direct

tiu asta.

o completiv direct

tiu c e bine pregtit.

o complement indirect

Ne bucurm de pregtirea lui.

o completiv indirect

Ne bucurm c e bine pregtit.

o element predicativ suplimentar

Este cunoscut ca specialist.

o

2)

o complement circumstanial

I-a uimit cu pregtirea sa.

o circumstanial

I-a uimit cu ct e de bine pregtit.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

9

o Notice that there is no subordinate clause corresponding to the Romanian nume

predicativ; for an explanation, it would be useful to resort to the definition of the subordonata

predicativ

10

.

o Also notice that there is no subordinate clause corresponding to the Romanian element

predicativ suplimentar.

It would be more difficult to produce such a table about the English elements because of the different

approach mainstream English grammars take to the classification of the subordinate clauses. However,

the analysis of the complex sentence is not within the scope of this course.

As Downing and Locke note, an important property of language is the fact that there is no one-

to-one correspondence between the class of unit and its function. While it is true that certain

classes of unit typically realise certain functions [], it is nevertheless also true that many

classes of unit can fulfil many different functions, and different functions are realised by many

different classes of unit. (2006, pp. , 19). To illustrate this, they propose the following examples:

FUNCTION REALIZATION

subject Next time will be better.

adjunct Ill know better next time.

direct object Well enjoy next time.

2.6. Phrases

2.6.1. Definition

In English grammar, the term phrase defines a word or group of words which can fulfil a

syntactic function in a clause. In an informal description, phrases are described as bloated

words, in that the parts of the phrase that are added to the head elaborate and specify the

reference of the head word (Hasselgrd, Lysvg, & Johansson, Glossary of grammatical terms

used in English Grammar: Theory and Use (2nd edition)).

The elements of the clause in the example below (subject, verbal, subject complement) are

realised as follows: the subject is realised by the noun phrase the girl in blue, the verbal by the

verb phrase was and the subject complement by the noun phrase his best friend. These

realisations can be shown by using labelled bracketing

11

.

[

NP

The girl in blue] [

VP

was] [

NP

his best friend]

As you know from the Romanian language classes you have taken until now, the phrase as such

has no correspondent in Romanian traditional grammar. However, in the more recent approaches

adopted by Gramatica Academiei (GALR 2008) and Gramatica de baz a limbii romne

10

Propoziia care ndeplinete funcia de nume predicativ se numete predicativ .

11

Labelled bracketing is a method of representing the structure of a phrase by using square brackets to the left and

right side of its constituents (words). The brackets carry subscripts (labels), which state the class of the unit in

question.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

10

(GBLR 2010), the analogous unit is called grup

12

(grup nominal, grup verbal, etc.), as illustrated

below

13

.

[

GN

Fata n albastru] [

GV

era] [

GN

prietena lui cea mai bun]

One observation can facilitate the identification of phrases in both English and Romanian: unlike

in traditional Romanian grammar, the phrases - not the words! - fulfil syntactic functions.

2.6.2. Structure of phrases

At syntactic level, a phrase works as a unit, that is, the whole group has a single syntactic

function. Nevertheless, since phrases can be made up of more than one word, they have an

internal structure and several rules order their constituents

14

.

A phrase contains a head and a number of dependant(s)/modifier(s). According to Leech (1992,

pp. , 51), the head is the obligatory element in a phrase, while the modifiers are optionally added

to qualify its meaning. He provides three examples - (friendly) places (to stay), (extremely) tall,

(more) often (than I expected) where the parts in parentheses are modifiers, and those not in

parentheses are the heads of their phrases

15

.

The two structures below illustrate the prototypical English noun phrase and the Romanian

grup nominal, respectively.

English: [

NP

[determiner(s)] [modifiers(s)] head [modifier(s)]

Romanian: [

GN

[Determinant] [Cuantificator] Centru [Modificator] [Posesor] [Complement]]

According to phrase structure grammar originally introduced by Noam Chomsky, but in

simplified terms, the following propositions should be considered about the structure of phrases:

Phrases are generated by rules of grammar (phrase structure rules).

These rules determine:

- which categories go into a phrase

- how categories are ordered

- which constituent is the head of the phrase

As the most important word in a phrase, the head carries the meaning of the phrase and

gives the name of the whole group. Thus, if the head word is a noun, the group is a noun

phrase. Verbs name verb phrases, adjectives - adjective phrases, adverbs - adverb phrases

and prepositions prepositional phrases

16

.

12

Grupul sintactic reprezint o proiecie a unui centru, realizat pe baza disponibilitilor sintacticosemantice ale

acestuia. La primul nivel de proiecie a centrului se gsesc complementele, componente obligatorii sintactico-

semantic, iar la al doilea nivel, adjuncii, componente facultative. (Nicolae, 2011)

13

They use the notation system proposed by the definition above.

14

In syntactic analysis, a constituent is a word or a group of words that functions as a single unit within a

hierarchical structure. The analysis of constituent structure is associated mainly with phrase structure grammars,

although dependency grammars also allow sentence structure to be broken down into constituent parts. (Constituent

(linguistics))

15

By convention, optional elements are normally placed between parentheses or brackets.

16

In some grammars, the prepositional phrase is not described in terms of head and modifier(s), one argument being

that both parts are needed in order to construct a prepositional phrase (cf. (Hasselgrd, Lysvg, & Johansson,

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

11

Unlike the other constituents, the head of a phrase cannot be omitted.

Phrases have a hierarchical structure. They can contain other phrases or clauses due to

embedding processes.

2.6.3. Embedding

In a definition provided by Leech (2006, pp. , 37), embedding/nesting is seen as the inclusion of

one unit as part of another unit of the same general type. He exemplifies the embedding of one

phrase inside another with the phrase [at [the other end [of [the road]]]], where one

prepositional phrase [of the road] is embedded in another [at the other end of the road]; also,

one noun phrase [the road] is embedded in another noun phrase [the other end of the road].

The subordination of clauses is recognized as another major type of embedding by the inclusion

of one clause (a subordinate clause) inside another one (the main clause). Downing and Locke

(2006, pp. , 28; 46) use the examples below to demonstrate the embedding of clauses

17

and some

syntactic functions they can fulfil as elements of the clause.

clause at S [That he left so abruptly] doesnt surprise me.

clause at dO I dont know [why he left so abruptly].

clause at oC He made the club [what it is today].

clause at Cs The question is [whether we can finish in time].

clause at A [After they had signed the contract] they went off to celebrate.

The same authors recognize the presence of recursive embedding when a series of clauses is

embedded, each within the previous one: I reminded him hed said hed find out about the flight

schedules. Here, the that-clause direct object of remind, which comprises the remainder of the

sentence, (hed said hed find out about the flight schedules) contains a further embedded that-clause

hed find out, which has a PP (about the flight schedules) as complement (Downing & Locke, 2006,

p. 105).

Embedding enables the expansion of linguistic units. In Greenbaum and Nelsons view (2002,

pp. , 49-50), embedding takes place in stages that are illustrated as follows:

- the first stage puts the sentence close to the noun it will be modifying:

a. He had a nasty gash. The gash needed medical attention.

- the next stage changes the noun phrase into a relative pronoun here which:

b. He had a nasty gash which needed medical attention.

The relative pronoun which functions as subject in the relative clause, while the gash functions

as subject in a., 2

nd

clause. The relative pronoun can be replaced by relative that:

Embedding is a widespread phenomenon in English; it can be described as a type of

subordination at phrase or clause level and, by it, a clause functions as a constituent of another

phrase or clause.

2.7. Words

Glossary of grammatical terms used in English Grammar: Theory and Use (2nd edition)). Similarly, the verb

phrases as well are not normally described in terms of head and modifier(s).

17

The embedded clauses are enclosed in square brackets.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

12

2.7.1. Definition and characteristics

Words are the penultimate of the five levels in the grammatical hierarchy. They are below

sentences, clauses, and phrases and above morphemes (see 2.4., 2.5., 2.6.).

Unlike sentences, clauses, and phrases (that justify their existence only as linguistic entities), words

have both a referential and a linguistic meaning.

The referential meaning acts as name/label for all the objects (= things, actions, events,

qualities) and notions (= opinions, meanings, ideas, concepts) outside the language, so that it is

extra-linguistic. It is also called dictionary meaning, and it must be distinguished from linguistic

meaning, which is not available in a dictionary. This course almost exclusively approaches the

linguistic meaning of words which are consequently seen as the building-blocks of phrases.

A comprehensive definition of what words are is far from simple. As Haspelmath puts it, it

seems that most languages have a word for 'word', the smallest unit of language that people with

no training in linguistics or writing have an awareness of (2002, p. 163).

Linguists (Carstairs-McCarthy, 2002; Katamba 2006; Fasold & Connor-Linton 2008; Meyer 2009;

Brjars & Burridge 2010) commonly agree that words can be identified by a number of criteria,

such as:

They possess a regular stress pattern, the can be preceded or followed by pauses in speech

or separated from one another by means of spaces and punctuation marks, in writing, as in

The boy is reading a book.

They are the minimal possible unit in an utterance, as in the exchange Can we go now?/

Yes.

They are assigned one or more dictionary meanings: boy 1. a male child or a male person

in general: The boys wanted to play football. 2. a son: How old is your little boy?

(Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English)

The above-mentioned conditions are met to various degrees and depend on the nature of each

word.

2.7.2. Orthographic word, grammatical word, lexeme

Biber, Conrad and Leech (2002, p. 15) identify three senses of 'word':

1. Orthographic words, as the words that we are familiar with in written language, where they

are separated by spaces. For example, They wrote us a letter contains five distinct orthographic

words.

2. Grammatical words, as units that fall into different grammatical word classes/parts of

speech. Thus the orthographic word leaves can be either of two grammatical words: a verb (the

present tense -s form of leave) or a noun (the plural of leaf). This is the basic sense of 'word' for

grammatical purposes.

3. Lexemes, as a set of grammatical words which share the same basic meaning, similar forms,

and the same word class. For example, leave, leaves, left, and leaving are all members of the verb

lexeme leave.

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

13

In Romanian the lexeme is defined as 1. cuvnt sau parte de cuvnt care servete ca suport

minimal al semnificaiei; morfem lexical. 2. unitate de baz a vocabularului care reprezint

asocierea unuia sau a mai multor sensuri; cuvnt; unitate lexical (ro.wiktionary).

A lexeme is a word that roughly corresponds to a dictionary entry. For instance, play would have

two entries in the dictionary, as a verb and as a noun. These are the lexemes, the basic forms. The

verb would appear in various forms when used in sentences, while the noun would have other

forms:

Verb lexeme: play. Forms of the lexeme: play, plays, played, playing

Noun lexeme: play. Forms of the lexeme: plays (pl.), plays; plays (genitive)

2.7.3. Morphological structure of words

The smallest constituent of words is called morpheme. By definition, a morpheme is a minimal

unit of meaning; in other words, a morpheme is characterised by two basic features: it has

meaning and it is indivisible.

Morphemes are different from syllables, and the number of syllable does not usually equal the

number of morphemes. The word tennis, for example, can be divided into two syllables (tennis),

yet it consists of one morpheme only, which in this case, is identical to the word. The smaller units

(the syllables ten- and-nis) bear no meaning of their own.

As we have already seen in 2.1., morphemes are classified as free morphemes and bound

morphemes on the one hand, and as roots and affixes, on the other. Free morphemes can stand

alone (charm, duty, man, animal, etc.) and cannot be divided into smaller meaningful units, while

bound morphemes/affixes cannot occur as independent words and are attached to other

morphemes to build words: charming, dutiful, manly, animalism, etc..

There are two types of affixes: prefixes (added to the beginning of a word) and suffixes (added to the

end of a word). For examples of derivational and inflectional morphemes, see the table in 2.1.

2.7.3. Word classes

A word class can be defined as a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially in

their inflections and distribution (see above).

There are two major types of word classes

1. lexical (or open) classes, that include nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. The words

belonging to the open class are also called lexical or content words.

2. function (or closed) classes, that mainly include determiners, pronouns, particles and

prepositions. The words belonging to the closed class are also called function or grammatical

words

3. Besides these two, Biber, Conrad and Leech (2002, p. 16) identify a third class they name

inserts

18

. Inserts are found mainly in spoken language and do not form an integral part of a

syntactic structure, but tend to be inserted freely in a text (see 5.1.).

18

This class includes the elements that in Romanian are recognized either as construcii incidente or interjecii.

Construcie incident = un cuvnt, un grup de cuvinte sau o propoziie care nu are nici o legtur sintactic cu

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

14

All English words belong to one of these classes. Notice however that the adverb class is partly

open (i.e. adverbs of manner) and partly closed (i.e. time and place adverbs).

Word classes such as noun, verb, adjective, etc., are traditionally called parts of speech. The

table below contains the two categories of the major word classes.

open classes closed classes

noun pronoun

main verb auxiliary (verb)

adverb determiner

conjunction

preposition

Minor classes include the numerals (one, twenty-three, first) and some words that do not fit

anywhere and should be treated individually (the negative not and the infinitive marker to).

Especially the words that belong to one the major word classes may have more than one

grammatical form. The noun work has the singular work and the plural works; the verb work has

the base form work and the past worked.

The discussion of word-classes should be based on the previous remarks in this section, where

the basic relationships between word, lexeme, morpheme, lexical and function words were

highlighted. For reasons of clarity and comprehensibility, we can also draw on Kies diagram

below (Kies).

restul enunului, ci reprezint o comunicare de sine stttoare. O propoziie incident (zise el, cred eu, m

gndesc) se reduce adesea la un verb i la subiectul acestuia, care este frecvent plasat dup verb. Verbul unei

propoziii incidente este foarte frecvent un verb de declaraie de tipul a spune, a zice, a rspunde, a declara sau

de opinie, de tipul a crede, a gndi, a presupune. n limba vorbit apar frecvent cuvinte sau propoziii incidente

care nu comunic nimic, sunt golite de sens, ca: Domnule!, Soro!, M rog, Nu-i aa?, Ce mai? (Forscu)

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

15

Kies notes that traditional grammar describes word classes as a combination of the bases and the

function words. The bases are called the open classes (because new words can be created in each

of those categories), while the function words are called the closed classes, since the speakers of

a language do not normally create new vocabulary in those categories. For example, it is easy to

create new nouns, but not new pronouns. He explains that speakers recognize word classes

through three different, but complementary, processes - the use of word endings, function

words, and word order, but that no process is totally efficient by itself.

Thus, though English employs a great number of word endings to signal different word classes,

the employment of endings alone does not identify all members of a word class, nor do they

identify all word classes. In order to demonstrate that speakers also rely on function words and

word order to distinguish one class from another, Kies uses a quote from Anthony Burgess A

Clockwork Orange and another from Carrolls "Jabberwocky"

19

, a nonsense verse poem in his

Through the Looking Glass that was also exploited by other linguists for discussions related to

English syntax (en.wikipedia.org).

1. The gloopy malchicks scattered razdrazily to the mesto.

2. 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gymble in the wabe

He maintains that people perceive the words brillig, slithy, gloopy, and razdrazily as modifiers

due to a combination of factors, including the suffixes -y (also spelt -i- when a second ending is

used on the same word, as in razdrazily) and -ly - two suffixes that mark adjectives and adverbs.

He also points to the fact that word endings are clues for the identification of the modifiers,

together with function words and word order. Thus, noun phrases have a predictable structure of

Determiner + Adjective + Noun (the clever children), so the combination of both determiners

(the) marking the beginning of noun phrases and word order in the sentences above help us

interpret slithy and gloopy as adjectives. Similarly, adjectives follow forms of the verb be when

the verb functions as a linking verb, as in Elizabeth is clever. So in the first sentence, the verb

was (part of the poetic fusion of it was into 'twas) helps us to interpret brillig as an adjective.

Finally, it is also common to find adverbs after verbs in English, as in Emily learns quickly,

which helps us to interpret razdrazily as an adverb in the last example sentence.

Kies concludes that speakers recognize patterns of word endings, function words, and

word/morpheme order when they do grammar, and that patterns are crucial in the discovery of

the constituents of language: recognizing patterns in distribution and meaning becomes the

process through which humans discover the grammatical structures of their languages (Kies).

In order to show that such recognition of linguistic patterns is not restricted to English, let us take

a look at a short text

20

.

19

A more detailed analysis of the linguistic relevance of Carrolls poem can be found in Analyzing Grammar: An

Introduction, by Paul R. Kroeger, CUP 2005.

20

The text is taken from Nina Cassians Loto-Poeme (1972) and it is written in Sparg. Just like the language of

Jabberwocky, this is an imaginary language created by Nina Cassian. That is how the poet describes it: Limba

sparg am inventat-o n 1946 (am pomenit doar de avangardismul meu, de propensiunea mea structural spre

joc). Ion Barbu mi-a interzis s includ acele exerciii n volumul meu de debut. Mult mai trziu le-am

publicat n volumele Loto-Poeme (1972), n Jocuri de vacan (1983), nsumnd pn la ora asta, circa o duzin

de sparguri, ba pe unul l-am tradus i n sparga englez... (Cassian, 2001).

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

16

Huelu care-i huat,

N-are flean, nici cherbat.

Hueaua care-i huat

N-are cherb la trizat.

Even if, except have and be, the rest of the content words are incomprehensible, we can

recognize this text as Romanian for the same reasons that make Jabberwocky English. Although

referential meaning is erased by the employment of nonsensical words, the patterns of word

endings, function words and word order are specific to Romanian.

The prosodic pattern is also recognizable for the Romanian speaker, and we sense that the four-line

sequence is a strigtur

21

because of its rhythm and rhyme, as well as because of its binary

parallel structure.

After reading these lines, any native speaker of Romanian will react in the same way as Alice in Through

the Looking-Glass did to Jabberwocky:

'It seems very pretty,' she said when she had finished it, 'but it's RATHER hard to understand!'

(You see she didn't like to confess, ever to herself, that she couldn't make it out at all.)

'Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideasonly I don't exactly know what they are!''

(Dodgson).

However, even if we are not helped by Humpty Dumpty who could explain all the poems that

were ever inventedand a good many that haven't been invented just yet.' (Dodgson), we can

understand that Huelu is a common noun with a suffixal definite article, masculine, animate

(probably human), while Hueaua is its female counterpart, also including the suffixal definite

article in the form of the noun. They are both qualified by the adjective huat (masc., sg.)/huat

fem., sg.), respectively. The huel does not possess a flean, nor a cherbat, while the huea does

not possess a cherb at her trizat. The fact that they do not possess such things can be either a

good thing or a bad thing, we cannot tell.

Unlike the grammatical units on the levels above - sentences, clauses, and phrases - the members

of word classes are normally single words. Nevertheless, multi-word units such the verb idioms

(phrasal verbs, prepositional verbs, phrasal prepositional verbs) or compound prepositions are

also classified as members of word classes.

The basic information about the rank scale of the units of language (discourse is not traditionally

described by grammar) can be revised as follows:

The sentence is the largest unit of language that grammar (traditionally) describes. It is a set of

words standing on their own as a sense unit, its conclusion marked by a full stop or equivalent

(question mark, exclamation mark). In many languages sentences begin with a capital letter, and

include a verb. (Ur 1999: 31) It is made up of one or more clauses.

The clause is a major unit of grammar, a kind of mini-sentence: a set of words which make a

sense unit (Ur 1999: 31), defined formally by the elements it may contain: subject (S), verbal

(V), object (O), complement (C) and adverbial (A). A clause is made up of one or more phrases.

21

Strigturile sunt structuri simple realizate, de obicei, n grupuri de 2-4 versuri cu exclamaii introductive cu caracter

epigramatic i adesea cu aluzii satirice sau glumee, uneori erotice, ori cu coninut sentimental, care se improvizeaz i

se strig, de obicei, n timpul executrii unor jocuri populare la sate. (Lascr, p. 4)

I. O. Macari, Morpho-syntax, Lecture 2 sem. I, 2014

17

A phrase is a shorter unit within the clause, made up of one or more words which fulfil the

grammatical function of a single word.

A word is the minimum normally separable form: in writing, it appears as a stretch of letters

with a space either side. (Ur 1999: 31) Each word can be further divided into one or more

morphemes.

A morpheme is a bit of a word which can be perceived as a distinct component (Ur 1999: 31),

the smallest meaningful unit that cannot be further divided.

In short, a sentence consists of one or more clauses, a clause consists of one or more phrases, a

phrase consists of one or more words, and a word consists of one or more morphemes.

Downing and Locke convincingly illustrate the relationship between the units with a one-word

clause.

Looking downwards, each unit consists of one or more units of the rank below it. []

For instance, Wait! consists of one clause, which consists of one group, which consists

of one word, which consists of one morpheme. More exactly, we shall say that the

elements of structure of each unit are realised by units of the rank below. Looking

upwards, each unit fulfils a function in the unit above it. (2006: 11)

It is important to approach one rank at a time (starting either upwards or downwards) in the

course of the analysis, because otherwise the constituents and functions would mix up. This

warning is very similar to the procedure in Romanian: you only deal with prile de vorbire

when you perform the morphological analysis, and with prile de propoziie when you perform

a syntactic analysis.

1. Identify the head in each of the following bracketed noun phrases:

1. [Cats] make very affectionate pets

2. [The editor] rejected the manuscript

3. We drove through [an enormous forest] in Germany

4. [People who cycle] get very wet

5. We really enjoy [the funny stories he tells]

2. Identify the phrase type:

1. Houses are [unbelievably expensive] just now.

2. We [met Paul] last week.

3. [A car that won't go] is not particularly useful

4. I enjoy eating [in Indian restaurants]

5. Don't you have to leave [early]?

6. Tell [him] not to worry.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- LabyrinthDocument3 paginiLabyrinthAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 2Document17 paginiLecture 2Ancuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CC ManualDocument279 paginiCC ManualTuckct100% (3)

- Cabin Crew Announcements Manual PDFDocument83 paginiCabin Crew Announcements Manual PDFvladutzu8989Încă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 16 - RevisionDocument4 paginiLecture 16 - RevisionAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 2-4Document87 paginiUnit 2-4Ancuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EEA Transcript of WorkDocument1 paginăEEA Transcript of WorkAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Grammar SecretsDocument66 paginiEnglish Grammar SecretsMbatutes94% (33)

- TrainingSalesStaff2015P PDFDocument17 paginiTrainingSalesStaff2015P PDFAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course TitleDocument7 paginiCourse TitleAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 7Document11 paginiLecture 7Ancuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 068 113 SurfingDocument46 pagini068 113 SurfingAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Ambitious GuestDocument7 paginiThe Ambitious GuestAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 8Document26 paginiUnit 8Ancuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENG142 Literature and Culture After 1900 Pensum 2014Document4 paginiENG142 Literature and Culture After 1900 Pensum 2014Ancuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- English LanuageDocument3 paginiEnglish LanuageAlina MuşatÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2009 FF UP Morphosyntax - Skripta-LibreDocument159 pagini2009 FF UP Morphosyntax - Skripta-LibreAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morph1 SlidesDocument41 paginiMorph1 SlidesAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course TitleDocument7 paginiCourse TitleAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1Document29 paginiLecture 1Ancuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joburi NoiDocument2 paginiJoburi NoiAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LA Erasmus 2014 - 2015 IncomingDocument17 paginiLA Erasmus 2014 - 2015 IncomingAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- XDocument2 paginiXAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LA Erasmus 2014 - 2015 IncomingDocument16 paginiLA Erasmus 2014 - 2015 IncomingAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anexa I Learning AgreementDocument2 paginiAnexa I Learning AgreementAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- African Americans Suport CursDocument4 paginiAfrican Americans Suport CursAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curs 3 - Medieval Literature 1Document13 paginiCurs 3 - Medieval Literature 1Ruxandra OnofrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Europass CV 20131017 Igarzábal enDocument2 paginiEuropass CV 20131017 Igarzábal enAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 068 113 SurfingDocument46 pagini068 113 SurfingAncuta AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Empower Advanced - Unit 2 - GrammarDocument33 paginiEmpower Advanced - Unit 2 - GrammarFaridoon HussainzadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Express Pack A-Unit1Document60 paginiInternational Express Pack A-Unit1Nguyễn Hải NamÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Easy Way To Form (Almost) Any Question in EnglishDocument5 paginiAn Easy Way To Form (Almost) Any Question in EnglishchiragÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perfect Tenses Homework GuideDocument7 paginiPerfect Tenses Homework Guiderudy gutierrezÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Language Notes - Standard Vii Active and Passive VoiceDocument4 paginiEnglish Language Notes - Standard Vii Active and Passive VoiceSteveÎncă nu există evaluări

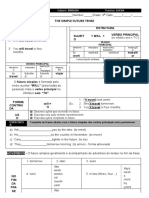

- The Simple Future Tense: Estrutura Sujeit O + Will + Verbo PrincipalDocument6 paginiThe Simple Future Tense: Estrutura Sujeit O + Will + Verbo PrincipalLucasÎncă nu există evaluări

- To Be Verbs AssignmentDocument3 paginiTo Be Verbs AssignmentTriana Andini PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parts of Speech QuizDocument2 paginiParts of Speech QuizEsaKhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Sanskrit-English Dictionary - Arthur A MacDonellDocument396 paginiA Sanskrit-English Dictionary - Arthur A MacDonellA.K. Aruna100% (2)

- Past Simple - Prepositions of TimeDocument21 paginiPast Simple - Prepositions of TimeAron Jerson AltamiranoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8 June 16Document4 pagini8 June 16Sandra Liliana Paez MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan (Adjectives As Describing Words)Document5 paginiEnglish Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan (Adjectives As Describing Words)KC Cerdeña92% (262)

- Semicolon Usage in SentencesDocument9 paginiSemicolon Usage in SentencesPhyo Eaindray MyintÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Chapter Comparative-SuperlativeDocument13 paginiSample Chapter Comparative-SuperlativeNiki MavrakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- TOEFL Grammar-ReviewDocument11 paginiTOEFL Grammar-Reviewjesus rosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subj-Verb Agreement Exercise 3 - Indefinite PronounsDocument2 paginiSubj-Verb Agreement Exercise 3 - Indefinite PronounsKrystal Grace D. PaduraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Korean Grammar IDocument173 paginiKorean Grammar Iers_chan100% (2)

- Past Continuous Passive Lesson With WorksheetsDocument4 paginiPast Continuous Passive Lesson With WorksheetsSophie SophiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Permission (Expresses The Idea of Permission) - + ? 2. Ability, Capability. + - ? 3. Supposition, Probability. + - + + 4. Possibility. +Document3 paginiPermission (Expresses The Idea of Permission) - + ? 2. Ability, Capability. + - ? 3. Supposition, Probability. + - + + 4. Possibility. +яковÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbstractDocument2 paginiAbstractDozdi100% (2)

- Conjugation of Spanish VerbsDocument16 paginiConjugation of Spanish VerbsSteven IStudy Smith100% (2)

- Grammar and vocabulary abilitiesDocument1 paginăGrammar and vocabulary abilitiesCésar PonceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Continuous What Are They Doing On Saturday Grammar Drills Oneonone Activities - 139314Document2 paginiPresent Continuous What Are They Doing On Saturday Grammar Drills Oneonone Activities - 139314Hsu Lai WadeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cook, Claire Kehrwald - The MLA's Line by Line, How To Edit Your Own Writing (1985)Document243 paginiCook, Claire Kehrwald - The MLA's Line by Line, How To Edit Your Own Writing (1985)Ting Guo100% (13)

- Present Perfect Simple vs Present Perfect ContinuousDocument13 paginiPresent Perfect Simple vs Present Perfect ContinuousCarolina SepúlvedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9th Class Digest SampleDocument7 pagini9th Class Digest SampleVaishali Wanwade72% (18)

- Guide To Pali Grammar PDFDocument29 paginiGuide To Pali Grammar PDFVen IndakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CC 6 Si CD CLX Modals - KEYDocument2 paginiCC 6 Si CD CLX Modals - KEYsurya deepanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeopardy TemplateDocument33 paginiJeopardy TemplateKasiita Ayagala Obusiramu EdrissouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Key Understan Ding To Be Developed Learning ObjectivesDocument118 paginiKey Understan Ding To Be Developed Learning ObjectivesJaymar Tuatis100% (1)