Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hitler y El Poder de La Estetica - Review PDF

Încărcat de

GabrielaRmerDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hitler y El Poder de La Estetica - Review PDF

Încărcat de

GabrielaRmerDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

THE HISTORIAN

studying people's religious beliefs. He posits that not everyone had a religious con-

version in the sixteenth century that would make them convinced Protestants. Rather,

he suggests, it would be better to analyze the ways in which people were changed by

the new forms of religious worship that were imposed from above. What were the

politics of reform and reformation? How did the politics change the religious beliefs

and practices of the majority of the English? How did the people, either elite or

common, negotiate religious change and use it for their own purposes? All of his ques-

tions are interesting. At the beginning and end of each section of his book, if not at

the beginning and end of each chapter, he informs the reader of why the revisionists

(i.e., Scarisbrick, Haigh, and Duffy) have it wrong. This reviewer found the format

annoying and at times wondered if the author was simply setting up straw men to

demolish. Perhaps he would have served himself better to show that the revisionists

did not look at the entire picture, rather than repeat how wrong they were.

Ethan H. Shagan is the first author recently to emphasize that the Reformation was

framed by Cromwell, Henry VIII, and Edward VI's councils in terms not of heresy and

true belief, although preachers may have used that language, but in terms of political

obedience. How did the English, a people schooled in obedience, react to this change?

The author believes that any conservative reaction and opposition to the imposition

of the royal supremacy or reform was doomed because the Catholics were divided

among themselves-e.g., only a small group of people objected to the royal supremacy,

and the Pilgrimage of Grace did not have unified goals. He then examines how the

people took part in, and profited from, the dissolution of the monasteries and chantries

and what the latter did to their belief in purgatory and intercessory prayer.

The author does occasionally say things that led this reviewer to wonder if he

understands some of the religious material. In commenting on a parish protest over

the changes of 1536, he relates the story of a young man who stuck a piece of pudding

in a priest's mouth, "rendering him ritually unclean and preventing him from per-

forming his duties" (58). The issue is not whether the priest was ritually impure or

not-the

6

nly instance of ritual impurity from medieval religion that comes to mind

is childbirth, and even that is open to discussion-but breaking a fast imposed by

both tradition and canon law. Receiving communion after breaking the fast was a

mortal sin. In analyzing the differences between Catholic and Protestant positions on

the effect of the death of Jesus on original sin and postbaptismal actual sin, the author

discusses Catholics and venial sin, but not mortal sin.

Despite such reservations, the book should be read by anyone interested in the reli-

gious history of Tudor England.

Xavier University John J. LaRocca

Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. By Frederic Spotts. (Woodstock and New York:

Overlook Press, 2003. Pp. xxii, 456. $37.50.)

Almost all biographies of Adolf Hitler have noted his artistic obsessions, particularly

with opera, painting, and monumental architecture. But before the publication of this

study, only Joachim C. Fest suggested that Hitler "regarded cultural productions as

892

BOOK REVIEWS

the real legitimation of his achievements as a statesman" (Hitler, 1973, p. 528).

Echoing this view, Frederic Spotts, a former American career diplomat, argues

that Hitler was convinced "that the ultimate objective of political effort should be

artistic achievement" (xi). The author relies primarily on published and unpublished

sources that document Hitler's comments on art and on the diaries and memoirs of

Joseph Goebbels and others from Hitler's former entourage. For specialists, the book

covers familiar terrain. Still, the work is valuable for both the general reader

and scholars because it is the most comprehensive and competent single-volume

summary of Hitler's artistic views and his attempts to implement them during the

Third Reich.

Spotts agrees with contemporary observers, like Albert Speer, and biographers,

such as Joachim Fest, that Hitler was interested in power only as a means for "achiev-

ing his cultural ambitions" (15). The author concentrates on Hitler's efforts "to create

a culture-state in which Germans were to listen to music he liked, attend operas he

loved, see paintings and sculptures he collected and admire the buildings he con-

structed" (401). Spotts describes his taste in the visual arts and music as reactionary.

However, in architecture, Hitler was an "eclectic functionalist" who eventually

accepted modern technology, including skyscrapers. The author recounts in great

detail Hitler's unsuccessful efforts to create quality Nazi music, paintings, and sculp-

tures. Hitler was able to denigrate modern art and purge Jews from the artistic world

in Germany, but he realized himself that the Nazi era produced no great painters. And

even though he did less harm to music than he did to painting or sculpture, there was

no music revolution either. In time, Hitler hoped that the Bayreuth Wagner festivals

would "Wagnerize" Germans. Hitler failed to produce great Nazi works in music and

the visual arts, but according to Spotts, he had at least "the minimal ability and the

maximal power to construct the buildings he wanted" (335). But his major urban

reconstruction plans were not realized except, perhaps, in the Autobahn (highways),

which the author claims Hitler saw as "aesthetic monuments" (386).

Spotts's discussion of Hitler's artistic tastes and plans is illuminating and interest-

ing, but he does not offer a satisfactory explanation of how genocide and culture were

connected in Hitler's mind. The author acknowledges that Hitler's two major goals

were "racial genocide and the establishment of a state in which the arts were supreme"

(30). And he notes that race "established an indivisible link between his cultural and

political views" (16). Yet Spotts maintains that "racial genocide and the military dom-

ination of Europe did not grow out of his aesthetic ideals" (11). Still, the reader is

left with a valuable discussion of Hitler's artistic visions, and that, of course, was the

author's primary goal.

Mississippi State University

Johnpeter Horst Grill

When the King Took Flight. By Timothy Tackett. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press, 2003. Pp. xiii, 270. $24.95.)

The Bourbons reigned in France for approximately two hundred years from the six-

teenth to the eighteenth centuries, but the two most determining events during that

893

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TITLE: [Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics]

SOURCE: Historian 66 no4 Wint 2004

WN: 0436002994070

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it

is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in

violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher:

http://www.troyst.edu/organization/phialphatheta

Copyright 1982-2004 The H.W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Earthly Powers: The Clash of Religion and Politics in Europe, from the French Revolution to the Great WarDe la EverandEarthly Powers: The Clash of Religion and Politics in Europe, from the French Revolution to the Great WarEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (35)

- Hitler's Mentor: Dietrich Eckart, His Life, Times, & MilieuDe la EverandHitler's Mentor: Dietrich Eckart, His Life, Times, & MilieuEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (2)

- 'And The Cock Crowed Again': Essays on Political Ideology and German Church HistoryDe la Everand'And The Cock Crowed Again': Essays on Political Ideology and German Church HistoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poets of Protest: Mythological Resignification in American Antebellum and German Vormärz LiteratureDe la EverandPoets of Protest: Mythological Resignification in American Antebellum and German Vormärz LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Wind From the East: French Intellectuals, the Cultural Revolution, and the Legacy of the 1960s - Second EditionDe la EverandThe Wind From the East: French Intellectuals, the Cultural Revolution, and the Legacy of the 1960s - Second EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787De la EverandThe Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (55)

- Tomáš G. Masaryk a Scholar and a Statesman. The Philosophical Background of His Political ViewsDe la EverandTomáš G. Masaryk a Scholar and a Statesman. The Philosophical Background of His Political ViewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Austrian Mind: An Intellectual and Social History, 1848-1938De la EverandThe Austrian Mind: An Intellectual and Social History, 1848-1938Încă nu există evaluări

- The Great Democracies (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume 4De la EverandThe Great Democracies (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume 4Încă nu există evaluări

- These Immortal Creations: An Anthology of British Romantic PoetryDe la EverandThese Immortal Creations: An Anthology of British Romantic PoetryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938-1945De la EverandHitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938-1945Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5)

- Greg RussellDocument21 paginiGreg RussellRaymond LullyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why the Germans? Why the Jews?: Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the HolocaustDe la EverandWhy the Germans? Why the Jews?: Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the HolocaustEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (5)

- Book Reviews: Entertainment Industrialised Has Two Strengths: Its U.S.-France-U.K. ComparativeDocument3 paginiBook Reviews: Entertainment Industrialised Has Two Strengths: Its U.S.-France-U.K. ComparativeΜιλτος ΘεοδοσιουÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012 Anticatolicismo y Literatura GoticaDocument32 pagini2012 Anticatolicismo y Literatura GoticaarriotiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herbert Butterfield: History, Providence, and Skeptical PoliticsDe la EverandHerbert Butterfield: History, Providence, and Skeptical PoliticsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Desolation and Enlightenment: Political Knowledge After Total War, Totalitarianism, and the HolocaustDe la EverandDesolation and Enlightenment: Political Knowledge After Total War, Totalitarianism, and the HolocaustÎncă nu există evaluări

- Was Adolf Hitler A EurasianistDocument15 paginiWas Adolf Hitler A EurasianistIf We Do NothingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Religion and the Rise of History: Martin Luther and the Cultural Revolution in Germany, 1760-1810De la EverandReligion and the Rise of History: Martin Luther and the Cultural Revolution in Germany, 1760-1810Încă nu există evaluări

- History of English-Speaking People PDFDocument29 paginiHistory of English-Speaking People PDFIndra SanjayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder - Second EditionDe la EverandThree Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder - Second EditionEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Edward Said and the HistoriansDocument9 paginiEdward Said and the HistoriansMark RowleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hitler's Religion: The Twisted Beliefs that Drove the Third ReichDe la EverandHitler's Religion: The Twisted Beliefs that Drove the Third ReichÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Vienna to Chicago and Back: Essays on Intellectual History and Political Thought in Europe and AmericaDe la EverandFrom Vienna to Chicago and Back: Essays on Intellectual History and Political Thought in Europe and AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reformation without end: Religion, politics and the past in post-revolutionary EnglandDe la EverandReformation without end: Religion, politics and the past in post-revolutionary EnglandÎncă nu există evaluări

- E. Hobsbawm, 'C (For Crisis) ', London Review of Books 31 (2009) 12-13Document6 paginiE. Hobsbawm, 'C (For Crisis) ', London Review of Books 31 (2009) 12-13fruittinglesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joseph de Maistre, How A Catholic A ReactionDocument17 paginiJoseph de Maistre, How A Catholic A Reactionlomaxx21Încă nu există evaluări

- From Mutual Observation to Propaganda War: Premodern Revolts in Their Transnational RepresentationsDe la EverandFrom Mutual Observation to Propaganda War: Premodern Revolts in Their Transnational RepresentationsMalte GriesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gilbert Keith Chesterton - Heretics PDFDocument149 paginiGilbert Keith Chesterton - Heretics PDFJose P MedinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-EnlightenmentDe la EverandHow Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-EnlightenmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: British Literature and the British Nation(s): Writing Unity and DisunityDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: British Literature and the British Nation(s): Writing Unity and DisunityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Brook Farm and Utopian LiteratureDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Brook Farm and Utopian LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture and Political LegitimationDocument7 paginiArchitecture and Political LegitimationmarcheinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Political Art of Chesterton and OrwellDocument18 paginiThe Political Art of Chesterton and OrwellneocapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of ReligionDe la EverandActs of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of ReligionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (8)

- The Life & Pontificate of Pope Pius XII: Between History & ControversyDe la EverandThe Life & Pontificate of Pope Pius XII: Between History & ControversyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liberalism-Against-Itself-_Samuel-Moyn_-_Z-Library_-41-59Document19 paginiLiberalism-Against-Itself-_Samuel-Moyn_-_Z-Library_-41-59MIGUEL ALEGRETE CRESPOÎncă nu există evaluări

- 943b C Footnotes 2 3Document24 pagini943b C Footnotes 2 3Gregory HooÎncă nu există evaluări

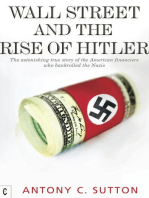

- Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler: The Astonishing True Story of the American Financiers Who Bankrolled the NazisDe la EverandWall Street and the Rise of Hitler: The Astonishing True Story of the American Financiers Who Bankrolled the NazisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Restoration Period (1660-1798)Document28 paginiRestoration Period (1660-1798)Tayyaba MahrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Third EditionDe la EverandHistoriography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Third EditionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (31)

- After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionDe la EverandAfter the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (26)

- Hitler and The Occult Roots of NazismDocument9 paginiHitler and The Occult Roots of NazismAdrianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Faithfully, Volume 2: Writings from the Archives: Frei’s Theological BackgroundDe la EverandReading Faithfully, Volume 2: Writings from the Archives: Frei’s Theological BackgroundÎncă nu există evaluări

- Explicación Molecular de La Inteligencia - FulltextThesis - R R Traill - 2007Document207 paginiExplicación Molecular de La Inteligencia - FulltextThesis - R R Traill - 2007GabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Haraway - A Cyborg Manifesto - ComentarioDocument9 paginiHaraway - A Cyborg Manifesto - ComentarioGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Género y MentoríaDocument9 paginiGénero y MentoríaGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fisica y Fiosofia de La Mente - Traill - BK1 - V28Document102 paginiFisica y Fiosofia de La Mente - Traill - BK1 - V28GabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geishas y MaikosDocument10 paginiGeishas y MaikosGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memoria y Quimica Magnetica Del Agua Water.2011.3.DemeoDocument47 paginiMemoria y Quimica Magnetica Del Agua Water.2011.3.DemeoGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mind and Micro-Mechanism - RR Traill - BK0 - MU6Document109 paginiMind and Micro-Mechanism - RR Traill - BK0 - MU6GabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coherent Infre Red .... - Traill 2011 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 329 012018Document24 paginiCoherent Infre Red .... - Traill 2011 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 329 012018GabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modelos Reduccionistas de La Mente - R R TraillDocument7 paginiModelos Reduccionistas de La Mente - R R TraillGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Darkest Germany-By V Gollancz - ReviewDocument5 paginiIn Darkest Germany-By V Gollancz - ReviewGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genocidio Bosnio Caso Prosecutor V - Nikolic - InglesDocument127 paginiGenocidio Bosnio Caso Prosecutor V - Nikolic - InglesGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paul de Man's Abyss - by Frank KermodeDocument13 paginiPaul de Man's Abyss - by Frank KermodeGabrielaRmer100% (1)

- The Psychology of Revolution by Le Bon, Gustave, 1841-1931Document187 paginiThe Psychology of Revolution by Le Bon, Gustave, 1841-1931Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- The Psychology of Revolution by Le Bon, Gustave, 1841-1931Document187 paginiThe Psychology of Revolution by Le Bon, Gustave, 1841-1931Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Critique of Security Politics - Mark NeocleousDocument8 paginiCritique of Security Politics - Mark NeocleousGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Resolute Desk: The President'S Desk The HistoryDocument2 paginiThe Resolute Desk: The President'S Desk The HistoryGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dieguez - Lucena - Pensando La TecnologíaDocument25 paginiDieguez - Lucena - Pensando La TecnologíaGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mumford - Authoritarian and Democratic TechnicsDocument9 paginiMumford - Authoritarian and Democratic TechnicsGabrielaRmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Study of Certain Theological Deviations in Desiderio DesideraviDocument16 paginiA Brief Study of Certain Theological Deviations in Desiderio DesideraviJosé Antonio UretaÎncă nu există evaluări

- "The Good Samaritan: Jewish Praise For Pope Pius XII" by Dimitri Cavalli in Inside The Vatican Magazine (October 2006)Document6 pagini"The Good Samaritan: Jewish Praise For Pope Pius XII" by Dimitri Cavalli in Inside The Vatican Magazine (October 2006)Dimitri CavalliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pieta Prayer Book 4-17-2019Document72 paginiPieta Prayer Book 4-17-2019JackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Politically Correct in The Church - EWTNDocument17 paginiPolitically Correct in The Church - EWTNjosephdwightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catholic Religious Education in Philippine Catholic Universities: A Critique On Catholic Religious Education in The PhilippinesDocument5 paginiCatholic Religious Education in Philippine Catholic Universities: A Critique On Catholic Religious Education in The PhilippinesRoy John R. Del RosarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Singing The MassDocument4 paginiSinging The Masskentclarck28Încă nu există evaluări

- Jesuits Yearbook 2012Document74 paginiJesuits Yearbook 2012John OxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saint Peter Damian, Gomorrah, and Today's Moral CrisisDocument5 paginiSaint Peter Damian, Gomorrah, and Today's Moral CrisisjgalindesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Breaking Free 12 Steps To Sexual Purity For Men Stephen Wood PDFDocument31 paginiBreaking Free 12 Steps To Sexual Purity For Men Stephen Wood PDFsrikanthÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Story of Johannesburg's Cathedral of Christ The KingDocument6 paginiThe Story of Johannesburg's Cathedral of Christ The KingLostJoburgÎncă nu există evaluări

- William Most - Commentary On GenesisDocument77 paginiWilliam Most - Commentary On GenesisMihai SarbuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethiopian Five Pillars of MysteryDocument49 paginiEthiopian Five Pillars of MysteryLucius80% (10)

- Theologia Catholica LatinaDocument129 paginiTheologia Catholica LatinaIldikó HomaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pope's 2015 Visit to the Philippines Boosted FaithDocument2 paginiThe Pope's 2015 Visit to the Philippines Boosted FaithJoshua EspirituÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Protestant Inquisition-Reformation Intolerance Persecut 1Document31 paginiThe Protestant Inquisition-Reformation Intolerance Persecut 1Quo PrimumÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1Document87 pagini1xubrylleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faith Development Day Workshop A "Tune-Up" For School LiturgiesDocument7 paginiFaith Development Day Workshop A "Tune-Up" For School Liturgiesthevaillants1Încă nu există evaluări

- Salesian SpiritualityDocument6 paginiSalesian SpiritualityNieves CrespoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biography of St. Joseph MarelloDocument2 paginiBiography of St. Joseph Marellojonna marie magayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flores de Mayo: Orientation-SeminarDocument6 paginiFlores de Mayo: Orientation-SeminarDaniel LewisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fall from Glory and Original Sin ExplainedDocument3 paginiFall from Glory and Original Sin ExplainedLawrence Sean MotinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pope Francis biography and factsDocument2 paginiPope Francis biography and factsAubrey MatiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roman CatholicismDocument2 paginiRoman Catholicismsizquier66100% (1)

- Political Law and Public International Law Must Read CasesDocument45 paginiPolitical Law and Public International Law Must Read CasesCrest PedrosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power of The Ideal UnitDocument18 paginiPower of The Ideal Unitapi-187838124Încă nu există evaluări

- John P. Meier (1978) - On The Veiling of Hermeneutics (1 Cor 11.2-16) - The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 40.2, Pp. 212-226Document16 paginiJohn P. Meier (1978) - On The Veiling of Hermeneutics (1 Cor 11.2-16) - The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 40.2, Pp. 212-226Olestar 2023-06-22Încă nu există evaluări

- Celebrating The SacramentsDocument97 paginiCelebrating The SacramentsCrafts CapitalPhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protestant Work Ethic and Spirit of CapitalismDocument4 paginiProtestant Work Ethic and Spirit of CapitalismInamu Rahman100% (1)

- Karl RahnerDocument5 paginiKarl RahnerHirschel HeilbronÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 WholeDocument360 pagini02 WholeLuigi NavalÎncă nu există evaluări