Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Group & Organization Management-2005-Goldberg-597-624 PDF

Încărcat de

Hneriana HneryDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Group & Organization Management-2005-Goldberg-597-624 PDF

Încărcat de

Hneriana HneryDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

http://gom.sagepub.

com/

Group & Organization Management

http://gom.sagepub.com/content/30/6/597

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1059601104267661

2005 30: 597 Group & Organization Management

Caren B. Goldberg

Decisions: Are we Missing Something?

Relational Demography and Similarity-Attraction in Interview Assessments and Subsequent Offer

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at: Group & Organization Management Additional services and information for

http://gom.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://gom.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://gom.sagepub.com/content/30/6/597.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Oct 20, 2005 Version of Record >>

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

10.1177/1059601104267661 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY

Relational Demography and

Similarity-Attraction in

Interview Assessments and

Subsequent Offer Decisions

ARE WE MISSING SOMETHING?

CAREN B. GOLDBERG

George Washington University

This study examines whether recruiter-applicant demographic similarity affects selection deci-

sions. In addition, the mediators proposed by the similarity-attraction paradigm were tested.

However, consistent with Graves and Powells (1995) findings and with the propositions of

social identity theory, I also proposed that female recruiters would prefer male applicants. Sig-

nificant race similarity effects were observed for White recruiters on overall interview assess-

ments and offer decisions, sex dissimilarity had a significant direct effect on overall interview

assessments, and age similarity was not related to either criterion. In addition, there was some

evidence that the significant direct effects were mediated by perceived similarity and interper-

sonal attraction. The sex dissimilarity effect appeared to be the result of male recruiters prefer-

ence for female applicants. Post hoc analyses revealed that this relationship was mediated by

applicant appearance.

Keywords: relational demography; applicant assessments; similarity-attraction; demographic

similarity; recruiter-applicant similarity; recruiter assessments

Organizational researchers have studied the impact of demographic vari-

ables on work outcomes for decades. During the past several years, however,

interest in demography has shifted away from simple effects toward more

complex relational demography models (cf. OReilly, Caldwell, & Barnett,

The author gratefully acknowledges the methodological assistance provided by Fran

Yammarino and Philip Wirtz and the constructive comments provided by Patrick McHugh and

Anne Tsui. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dr. Caren B.

Goldberg, Department of Management Science, George WashingtonUniversity, School of Busi-

ness and Public Management, Washington, DC 20052; phone: (202) 994-1590; fax: (202) 994-

4930; e-mail: careng@gwu.edu.

Group & Organization Management, Vol. 30 No. 6, December 2005 597-624

DOI: 10.1177/1059601104267661

2005 Sage Publications

597

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

1989; Tsui, Egan, &OReilly, 1992; Zenger &Lawrence, 1989). The central

idea of relational demography is that it is not an individuals demographic

characteristics, per se, that affect work attitudes and behaviors; rather, it is an

individuals demographic characteristics relative to a referent other or group

that explain these criteria. Specifically, relational demography predicts that

individuals who are similar to referent others will experience more positive

outcomes than will those who are dissimilar to referent others.

Despite the abundance of research that has linked demographic similarity

to work outcomes (Jackson et al., 1991; OReilly et al., 1989; Riordan &

Shore, 1997; Tsui et al., 1992; Tsui & OReilly, 1989; Zenger & Lawrence,

1989), only a handful of studies have examined the impact of demographic

similarity on applicant assessments in applied settings (Graves & Powell,

1995, 1996; Lin, Dobbins, & Farh, 1992; Prewett-Livingston, Field, Veres,

&Lewis, 1996). The present study builds on this research and addresses two

limitations of prior research: It includes several indices of recruiter-applicant

demographic similarity in the same model, and it includes recruiters imme-

diate, postinterview impressions as well as actual subsequent hiring deci-

sions. The current investigation makes an important theoretical contribution

as well. In response to Lawrences (1997) lament that organizational demog-

raphy researchers usually leave the concepts unmeasured and hypotheses

untested (p. 2), this study considers one of the intervening processes that

may explain why organizational demography affects selection.

DEMOGRAPHIC SIMILARITY AS A PREDICTOR

OF SELECTION OUTCOMES

A number of relational demography studies have suggested that demo-

graphic similarity in dyads results in favorable outcomes (Judge & Ferris,

1993; Lagace, 1990; Tsui & OReilly, 1989; Tsui, Xin, & Egan, 1995). The

conceptual rationale underlying this stream of research stems from social

identity theory. Social identity theory posits that individuals determine their

social identityby categorizing themselves, categorizing others, and attaching

value to different social categories (Gaertner &Dovidio, 2000; Tajfel, 1982;

Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner & Oakes, 1986). As individuals strive to

maintain consistent identities (Steele, 1988), evaluating similar others more

favorably than dissimilar others is one means by which an individual

maintains a positive identity (self-continuity drive).

Researchers have examined the impact of relational demographic charac-

teristics on employees work-related attitudes, intentions, and behaviors and

on supervisors assessments of employees (cf. Jackson et al., 1991; Riordan

& Shore, 1997; Tsui & OReilly, 1989). However, relatively little applied

598 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

research has examined the impact of recruiter-applicant similarity on organi-

zational entry outcomes (for exceptions, see Graves & Powell, 1995, 1996;

Lin et al., 1992; and Prewett-Livingston et al., 1996). The literature linking

person-organization fit to selection outcomes (Schneider, 1987) would sug-

gest that as recruiters presumably view themselves as successful organiza-

tional members, they will seek applicants who are demographically similar

to themselves, with the expectation that the applicants, too, will fit in the

organization (Judge &Ferris, 1991). Indeed, several laboratory studies have

provided evidence that recruiter-applicant race similarity (Rand & Wexley,

1975) and sex similarity (Heilman, Martell, & Simon, 1988; Wiley &

Eskilson, 1985) are positively related to selection decisions.

Despite the lack of applied research examining the impact of relational

demography on selection, there is reason to believe that relational demogra-

phys impact on selectionoutcomes should be at least as great as its impact on

other work criteria. Specifically, Pelled (1997) and Harrison, Price, and Bell

(1998) contend that initial categorizations are accompanied by perceptions

of similarity that are based on surface-level demographic data. Moreover,

Milliken and Martins (1996) suggest that diversity on observable attributes

creates more serious negative affective reactions than diversity on underly-

ing attributes (p. 415). For this reason, the present study focuses on those

demographic similarity variables that are easily observed (age, race, and

sex). Moreover, Ravensons (1989) and Gordon, Rozelle, and Baxters

(1988) findings that stereotyping is more apt to occur when minimal other

data about the target are available suggest that similarity biases may be more

pronounced in the context of an employment interviewthan in the context of

intact manager-employee dyads. Therefore, I predict that recruiter-applicant

demographic similarity will be positively related to selection outcomes.

Hypothesis 1a: Recruiter-applicant demographic similarity will have a direct pos-

itive effect on overall interview assessments.

Hypothesis 1b: Recruiter-applicant demographic similarity will have a direct pos-

itive effect on subsequent offer decisions.

SIMILARITY-ATTRACTION

The similarity-attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1971) is closely related to social

identity theory; however, the former elaborates on the intervening processes

that occur between recognition of a referent other as similar and the ensuing

favorable assessments of the referent other. In particular, the similarity-

attraction paradigm posits that individuals who are similar will be interper-

sonally attracted. Because of this attraction (liking), they will experience

positive outcomes. Although the early work on similarity-attraction focused

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 599

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

on attitudinal similarity (Byrne, 1971; Byrne & Clore, 1970), subsequent

research suggests that observable attributes, such as demographic character-

istics, likely affect interpersonal attraction as well. Specifically, Ferris,

Judge, Rowland, and Fitzgibbons (1994) and Tsui and OReilly (1989)

found that supervisor-subordinate demographic similarity was positively

related to supervisors liking of subordinates.

Although a number of researchers have examined whether demographic

similarity results in positive work attitudes and behaviors (Jackson et al., 1991;

OReilly et al., 1989; Riordan &Shore, 1997; Tsui et al., 1992; Tsui &OReilly,

1989; Zenger &Lawrence, 1989), they have relied on the similarity-attraction

paradigm as an assumption and have not tested it explicitly. That is, direct

links between demographic similarity and work criteria provide support for

the notion that demographics relative to others are important; however, these

links do not necessarily provide support for the underlying similarity-attrac-

tion framework. Such studies treat demographic similarity variables as indi-

cators of subjective concepts that explain the outcomes. An alternative per-

spective is that a subjective concept intervenes between the demographic

similarity variables and the outcomes (Lawrence, 1997). Graves and Powell

(1995) provide a comprehensive explanation of this intervening process in

the context of selection:

Demographic similarity between the recruiter and applicant on characteristics

such as sex leads to perceived similarity in attitudes and values which in turn

leads to interpersonal attraction between the recruiter and the applicant. Inter-

personal attraction then leads to positive bias in the recruiters interview

conduct. (p. 86)

Thus, the impact of demographic similarity on selection outcomes may be

viewed as a mediated process with multiple steps, with each step a little more

removed from the starting point. In the initial encounter, the recruiter

observes the applicants demographic characteristics and makes a determi-

nation as to whether these characteristics are similar or dissimilar to the

recruiters own demographics. If the recruiter is demographically similar to

the applicant, he or she is apt to presume that the applicant has attitudes and

beliefs that are similar to his or her attitudes and beliefs. The link between

perceived attitudinal similarity and interpersonal attraction can be traced

back to Byrne and Clore (1970) who proposed that agreement with another

person validates ones own beliefs and satisfies a drive to interpret the envi-

ronment correctly, and to function effectively in understanding and predict-

ing events (p. 118). When this drive is satisfied, an individual attaches posi-

tive affect to the source, as evidenced by their attraction to the source. The

600 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

similarity-attraction paradigm further posits that when we are attracted to a

referent other, we tend to make more favorable overall assessments of the

other. Indeed, both laboratory (Howard &Ferris, 1996) and field (Kinicki &

Lockwood, 1985; Wade & Kinicki, 1997) studies of the employment inter-

view have found significant relationships between affect and attraction

toward applicants and recruiters evaluations of them. Finally, consistent

with the notion that intentions lead to behaviors (Fishbein & Azjen, 1975),

there is some evidence in the selection literature that interviewers impres-

sions of applicants are linked to final offer decisions (Cable & Judge, 1997).

Thus, it is reasonable to expect overall interviewassessments to be positively

related to subsequent offer decisions. However, because several factors out-

side of the recruiter influence final offer decisions (e.g.., whether the appli-

cant is invited for an on-site interview), the direct effect of demographic sim-

ilarity on this outcome is likely smaller than is the direct effect of

demographic similarity on recruiters postinterview assessments. The fore-

going suggests that the relationship between demographic similarity and

final offer decision is mediated by several intervening variables, which are

depicted in Figure 1.

Hypothesis 2a: Recruiter-applicant demographic similarity will have an indirect

effect on overall interview assessments through perceived attitudinal similar-

ity and interpersonal attraction, such that recruiters will evaluate demographi-

cally similar applicants higher than demographically dissimilar applicants on

perceived attitudinal similarity and interpersonal attraction.

Hypothesis 2b: Recruiter-applicant demographic similarity will have an indirect

effect on offer decisions through perceived attitudinal similarity, interpersonal

attraction, and overall interviewassessments, such that recruiters will evaluate

demographically similar applicants higher than demographically dissimilar

applicants on perceived attitudinal similarity, interpersonal attraction, and

overall interview assessments.

AN ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVE OF RELATIONAL SEX

Although there has been a good deal of support for the relationships

proposed in the previous section, other studies suggest that the similarity-

attraction paradigm may be an inadequate explanation for the impact of sex

similarity on applicant assessments. In particular, Graves and Powell (1995)

found that sex similarity was unrelated to interpersonal attraction and inter-

view outcomes, but that it was negatively related to perceived similarity.

Specifically, whereas male recruiters saw male and female applicants as

nonsignificantly different with respect to perceived attitudinal similarity,

female recruiters perceptions of attitudinal similarity were greater for male

applicants than for female applicants. They argued that because women are

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 601

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

generally afforded lower status than are men, the female recruiters sought to

identify with the higher-status male applicants. Indeed, the social identity

theory (SIT) literature suggests that a second means by which individuals

maintain positive identity is by identifying with groups that are status-

enhancing (self-enhancement drive). This research suggests that individuals

may favor outgroup members over ingroup members if the outgroup enjoys

higher status than the ingroup does (Gaertner &Dovidio, 2000). Indeed, sev-

eral laboratory studies have demonstrated that membership in a low status

group is negatively related to identification with ones own group and posi-

tively related to favoritism toward outgroup members (Ellemers, Wilke, &

van Knippenberg, 1993; Sachdev & Bourhis, 1991). Likewise, applied

research suggests that females tend to identify with males to maintain a posi-

tive social identity (Ely, 1994, 1995; Gutek, 1985) and that the drive for self-

enhancement moderates the relationship between sex similarity and work

outcomes (Goldberg, Riordan, & Schaffer, 2003).

Further evidence to support the contention that women may identify more

with men than with other women comes from research on gender roles. In

particular, Konrad, Corrigall, Lieb, and Ritchie (2000) found that womens

preferences for male-typed job attributes are greater for female managers

than for female students. Moreover, Konrad, Ritchie, Lieb, and Corrigall

(2000) found that whereas in the general population women and men dif-

fered significantly in their preferences for various job attributes, women who

were in masculine-typed occupations had very similar job attribute prefer-

ences to men. Likewise, Kirchmeyer (2002) examined the stability of mascu-

linity and femininity longitudinally and found that female managers femi-

ninity decreased significantly during a 4-year period, suggesting that

femininity is negatively related to career success for women. Together, these

findings suggest that women with more masculine-typed attitudes toward

work are more likely to select and remain in masculine-typed occupations.

602 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

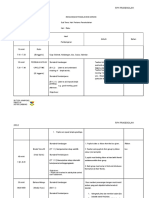

Observable

Demographic

Similarity

Age

Race

Sex

Perceived

Similarity

Interpersonal

Attraction

Overall Interview

Assessments

Offer

Decision

Figure 1: Proposed Similarity-Attraction Model

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Thus, female recruiters may see male candidates as more similar to them-

selves (in terms of femininity) than female candidates. Consequently,

women in successful jobs (such as recruiters) are likely to identify more with

men than with other women. Moreover, the great majority of the jobs for

which applicants were interviewing are stereotypically masculine jobs

(Goldberg, Finkelstein, Perry, & Konrad, in press), strengthening the suit-

ability of male applicants. Consequently, I propose that sex similarity will be

negatively related to the outcomes for women.

Hypothesis 3a: Recruiter-applicant sex similarity will have an indirect effect on

overall interview assessments through perceived attitudinal similarity and

interpersonal attraction, such that female recruiters will evaluate female appli-

cants lower than male applicants on perceived attitudinal similarity and inter-

personal attraction, whereas male recruiters will not distinguish between male

and female applicants.

Hypothesis 3b: Recruiter-applicant sex similarity will have an indirect effect on

offer decisions through perceived attitudinal similarity, interpersonal attrac-

tion, and overall interviewassessments, such that female recruiters will evalu-

ate female applicants lower than male applicants on perceived attitudinal simi-

larity, interpersonal attraction, and overall interview assessments, whereas

male recruiters will not distinguish between male and female applicants.

METHOD

SAMPLE

Participants included applicants and recruiters utilizing the career ser-

vices offices of three colleges in the southeastern United States between

March and June, 1996. Recruiting organizations represented a wide variety

of industries. A breakdown by industry category is presented in Table 1.

A similar process was used at all three schools: Companies provided the

career services office with a list of minimum qualifications, then the career

services office sent resumes of applicants who met those qualifications. In

some cases, the organizations prescreened resumes, asking that only a subset

of highly qualified applicants be scheduled for campus interviews. In other

cases, any applicants who met the minimum qualifications was permitted to

schedule an interview. As I was physically present to personally hand the sur-

veys to the recruiters at nearly all of the interviews, the response rate was very

high (90%). Each observation was composed of an applicant-recruiter dyad.

As every recruiter interviewed between 1 and 14 applicants (M = 7.7), there

was a total of 311 pairs, representing the matching of 45 recruiters with 210

applicants. All 311 dyads were used for the analyses involving perceived

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 603

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

similarity, interpersonal attraction, and overall interview assessments; how-

ever, because of the drop-off rate of recruiters responding to the follow-up

survey, there were only 273 pairs for the analyses involving subsequent offer

decisions.

The recruiters included 23 human resource professionals and 22 manag-

ers in the departments for which the organizations were recruiting. Their

average age was 37.5 years (SD = 8.19), and their average company tenure

was 6.73 years (SD= 6.82). Nearly 66%were male, and 88.6% had at least a

college degree. All recruiters were either Caucasian (81.7%) or African

American (18.3%).

The average age of applicants was 27.5 years (SD = 6.04). Most (65.7%)

were male, and 78.1% were completing (or had recently completed) their

bachelors degrees. Approximately 62% were Caucasian, 18.6% were Afri-

can American, 11.4% were Asian, and 5.2% were Hispanic. The most popu-

lar majors of applicants were information systems (13.8%), finance (12.4%),

marketing (8.6%), and management (7.2%).

PROCEDURE

College A provided a list of the names and telephone numbers of recruit-

ers who would be participating in campus interviews. Prior to the interview

date, I contacted the recruiters by telephone to discuss their participation. On

the day of the interviews, I met with the recruiters when they arrived to

remind them about the study and to provide them with their surveys. Two

604 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

TABLE 1

Industrial Classifications of Recruiting Organizations

Industry Category Percentage of Organizations

Banking 11.1

Consulting services 2.2

Financial services 2.2

Government 4.4

Hospitality 4.4

Manufacturing, consumer products 13.3

Manufacturing, high technology products 15.6

Manufacturing, industrial products 11.1

Retail 8.9

Services, other 15.6

Telecommunications 11.1

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

separate types of surveys were provided. The first survey was completed

prior to conducting any interviews. It asked respondents to provide demo-

graphic information about themselves and to evaluate applicants solely on

the basis of their resumes. Recruiters were given one copy of the second sur-

vey for each applicant they would be interviewing. To eliminate memory

biases, they were asked to complete these surveys immediately following

each interview. In almost all cases, the recruiters handed the completed sur-

veys back to me prior to leaving. In a few instances, however, they mailed

them in a preaddressed envelope.

At Colleges B and C, the process was similar, with some minor excep-

tions. First, the directors of the career services offices telephoned the recruit-

ers to discuss their participation. Second, on occasion, the director of the

career services office at College B handed the packets to the recruiters and

requested their participation on my behalf. Last, at College A, applicant

demographic data were provided by the career services office. At Colleges B

and C, this information was provided on a survey administered to applicants

for other purposes.

I contacted the recruiters by telephone between 2 and 4 months after the

campus interviews. At that time, they indicated which applicants had been

offered jobs with their organization.

MEASURES

Control variables. Recruiters assessments are primarily driven by their

assessments of applicants scholastic standing and work experience

(Dipboye, 1992). Thus, an itemthat asked respondents to evaluate the appli-

cant relative to other applicants they would be interviewing, solely on the

basis of his or her resume, was used as a control variable. Responses ranged

from 1 (very unqualified) to 5 (very qualified). Although Dipboye (1992)

notes that resumes may be contaminated with demographic information, the

correlations between the resume variable and each of the applicant demo-

graphic characteristics were nonsignificant, suggesting that recruiters did not

consider demographic information in their assessments of applicants

resumes. The age, race, and sex of applicants and recruiters were also

included as control variables. Age was continuous; sex was coded as 1 for

males and 1 for females. Race was coded as 1 for Caucasians and 1 for Afri-

can Americans (race-similarity analyses were limited to dyads comprising

applicants of these two groups because all recruiters were either Caucasian or

African American).

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 605

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Demographic similarity. Edwards (1994) notes that similarityon continu-

ous variables is best captured by polynomial expressions, as this approach

avoids many of the limitations of difference scores. For example, difference

scores would treat a dyad in which the recruiter was 30 and the applicant was

25 identically to a dyad in which the recruiter was 50 and the applicant was

45. Likewise, as differences scores are typically calculated as absolute val-

ues, they fail to distinguish between dyads in which the magnitude of age dif-

ference is the same but the direction of the relationship is different (i.e., a 30-

year-old applicant with a 25-year-old recruiter would be treated the same as a

25-year-old applicant with a 30-year-old recruiter). Thus, to measure age

similarity, I used polynomial terms. As polynomial terms comprise the sim-

ple effects for applicant age and recruiter age, their interaction, and the

squares of these terms, a significant effect is evidenced only when all

components are significant.

Because applicant and recruiter sex were effects coded (1/1), sex simi-

larity was computed as the interaction of these two variables. The effects

coding (1/1) of recruiter and applicant sex created interaction terms, such

that same-sex pairs were always positive and opposite sex pairs were always

negative. Male recruitermale applicant dyads represented 38% of the sam-

ple, male recruiterfemale applicant dyads represented 23.4%, female

recruitermale applicant dyads represented 21.3%, and female recruiter

female applicant dyads represented 17.3%. Race similarity was computed as

the interaction of the effects coded applicant race and recruiter race variables.

Of the dyads included in the race analyses, 56.6% comprised Caucasian

recruiterCaucasian applicant pairs, 20% comprised Caucasian recruiter

African American applicant pairs, 17.7% comprised African American

recruiterCaucasian applicant pairs, and 5.7% comprised African American

recruiterAfrican American pairs.

Mediators and outcomes. Byrnes (1971) 4-itemsimilarity scale was used

to measure perceived similarity. The alpha coefficient of the scale was .94.

Interpersonal attraction was assessed using Byrnes 2-item interpersonal

attraction scale (alpha = .93). Although Byrne used a 7-point scale, a 5-point

scale was used in the present study, with responses ranging fromstrongly dis-

agree (1) to strongly agree (5). The overall interview assessment measure

was composed of 3 items measuring the likelihood that the applicant would

be offered the job, the likelihood that the organization would consider the

applicant, and the likelihood that the applicant would be invited for an on-site

interview (alpha = .92). Responses ranged from strongly disagree (1) to

strongly agree (5). Between 2 and 4 months after the interviews, recruiters

606 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

indicated whether the applicant had been offered the job. Responses were

coded as 0 (not offered) and 1 (offered).

DATA ANALYSIS

Because each recruiter evaluated multiple applicants, the issue of

nonindependence of observations needed to be addressed prior to testing the

hypotheses. To address this issue, a dummy variable was created for each

recruiter. These dummy variables were used as controls.

Hierarchical linear regression was used to test the hypotheses regarding

overall interview assessments, interpersonal attraction, and perceived simi-

larity. However, for the dichotomous offer-decision criterion, logistic

regression was used. The incremental step test for this variable was the

2

improvement test, which is analogous to an F test (Menard, 1995).

As described in the next section, where significant direct effects were

found, these were followed-up with tests for mediation using the procedure

detailed by Baron and Kenny (1986) and by Kenny (1998).

As the recruiters role in the selection process may affect the results, I ran

the analyses with recruiter job type (1 =human resources, 2 =manager in the

department for which the organization was recruiting) as a control. Presum-

ably, those in the latter category play a larger role in the selection process.

However, this variable was not significant; therefore, I did not retain it.

RESULTS

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations are presented in Table

2. The results presented here provide some initial support for the proposed

similarity-attraction model.

To assess the independence of the constructs, a confirmatory factor analy-

sis was performed on the overall interviewassessment, perceived similarity,

and interpersonal attraction measures. Several fit indices were used to deter-

mine the suitability of the proposed three-factor model as compared to a

model in which all items were specified to load on a single factor. The one-

factor model did not fit the data:

2

= 1551.84, 27 df (p < .01); GFI = .50;

AGFI =.16; NFI =.65; CFI =.65; and RMR=.14. In contrast, although the

2

(190.48, 24 df) for the three-factor model was significant at p < .01, all of the

other measures indicated acceptable fit: GFI = .90; AGFI = .81; NFI = .96;

CFI =.96; and RMR=.04. Thus, the three-factor solution fit the data well.

The first hypothesis predicted that demographic similarity would affect

overall interview assessments and final offer decisions. The regression

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 607

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

608

T

A

B

L

E

2

M

e

a

n

s

,

S

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

D

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

s

,

a

n

d

I

n

t

e

r

c

o

r

r

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

M

S

D

1

.

2

.

3

.

4

.

5

.

6

.

7

.

8

.

9

.

1

0

.

1

1

.

1

2

.

1

3

.

1

4

.

1

5

.

1

6

.

1

.

A

p

p

l

i

c

a

n

t

a

g

e

2

7

.

5

0

5

.

9

3

1

.

0

0

2

.

A

p

p

l

i

c

a

n

t

r

a

c

e

.

1

7

.

9

8

1

2

*

1

.

0

0

3

.

A

p

p

l

i

c

a

n

t

s

e

x

.

1

8

.

9

9

.

1

0

.

2

1

*

*

1

.

0

0

4

.

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

a

g

e

3

6

.

6

8

7

.

9

4

.

0

6

.

1

3

*

.

0

4

1

.

0

0

5

.

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

r

a

c

e

.

4

1

.

9

1

.

0

3

.

0

1

.

0

6

.

1

7

*

*

1

.

0

0

6

.

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

e

x

.

1

2

.

9

9

.

0

3

.

0

9

.

0

7

.

1

9

*

*

.

4

5

*

*

1

.

0

0

7

.

A

p

p

l

i

c

a

n

t

r

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

a

g

e

.

7

1

*

*

.

0

1

.

1

3

.

7

3

*

*

.

0

6

.

1

4

*

*

1

.

0

0

8

.

A

p

p

l

i

c

a

n

t

a

g

e

2

.

9

9

*

*

.

1

3

*

.

0

9

.

0

5

.

0

2

.

0

3

.

7

0

1

.

0

0

9

.

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

a

g

e

2

.

0

7

.

1

4

*

.

0

3

.

9

9

*

*

.

1

7

*

*

.

1

8

*

*

.

7

4

*

*

.

0

6

1

.

0

0

1

0

.

R

a

c

e

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

.

0

2

.

4

1

*

*

.

0

9

.

0

7

.

1

5

*

*

.

1

8

*

*

.

0

5

.

0

2

.

0

8

1

.

0

0

1

1

.

S

e

x

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

.

0

8

.

0

2

.

1

1

*

.

0

9

.

1

3

*

.

1

7

*

*

.

0

8

.

0

8

.

0

8

.

0

1

1

.

0

0

1

2

.

R

e

s

u

m

e

q

u

a

l

i

t

y

3

.

4

9

.

8

8

.

0

6

.

0

4

.

0

2

.

1

3

*

.

0

9

.

1

4

*

.

1

4

*

*

.

0

7

.

1

3

*

.

0

5

.

0

0

1

.

0

0

1

3

.

P

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

3

.

1

6

.

6

9

.

0

0

.

0

8

.

1

0

.

0

0

.

0

4

.

0

8

.

0

1

.

0

1

.

0

1

.

1

2

*

.

0

9

.

2

9

*

*

1

.

0

0

1

4

.

I

n

t

e

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

a

t

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

3

.

5

0

.

7

6

.

0

7

.

0

4

.

1

1

.

1

5

*

*

.

0

8

.

0

4

.

0

5

.

0

7

.

1

6

*

*

.

0

8

.

0

6

.

4

6

*

*

.

6

2

*

*

1

.

0

0

1

5

.

O

v

e

r

a

l

l

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

3

.

0

7

.

8

8

.

0

6

.

1

8

.

0

3

.

0

5

.

0

5

.

0

6

.

0

2

.

0

3

.

0

5

.

1

6

*

*

.

0

7

.

4

7

*

*

.

5

6

*

*

.

6

6

*

*

1

.

0

0

1

6

.

O

f

f

e

r

d

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

.

1

2

.

3

3

.

0

2

.

0

8

.

0

3

.

0

4

.

1

3

*

.

2

1

*

*

.

0

1

.

0

3

.

0

4

.

1

1

.

0

8

.

1

9

*

*

.

0

9

.

2

5

*

*

.

2

6

*

*

1

.

0

0

N

O

T

E

:

R

a

c

e

w

a

s

c

o

d

e

d

s

u

c

h

t

h

a

t

1

=

W

h

i

t

e

a

n

d

1

=

A

f

r

i

c

a

n

A

m

e

r

i

c

a

n

.

S

e

x

w

a

s

c

o

d

e

d

s

u

c

h

t

h

a

t

1

=

m

a

l

e

a

n

d

1

=

f

e

m

a

l

e

.

R

a

c

e

a

n

d

s

e

x

w

e

r

e

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

c

o

d

e

d

s

u

c

h

t

h

a

t

1

=

d

i

s

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

p

a

i

r

s

a

n

d

1

=

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

p

a

i

r

s

.

O

f

f

e

r

d

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

w

a

s

c

o

d

e

d

s

u

c

h

t

h

a

t

0

=

n

o

t

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

a

n

d

1

=

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

.

*

p

.

0

5

.

*

*

p

.

0

1

.

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

analyses for age, sex, and race similarity are presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5,

respectively. Contrary to expectations, age similarity was unrelated to either

of these criteria. Sex similarity had a significant impact on overall interview

assessments but was not significantly related to offer decisions. The nature of

this effect is displayed in the third panel of Figure 2. This plot shows that both

male and female recruiters gave more favorable overall interview assess-

ments to applicants of the opposite sex; however, this effect was far more

pronounced for male recruiters than for female recruiters. Although this pat-

tern was consistent with Hypothesis 3a, a post hoc comparison of means indi-

cated that female recruiters did not rate male applicants significantly more

favorably than female applicants.

Race similarity affected both overall interview assessments and offer

decisions, although the latter relationship was only of marginal significance.

The plots in Figure 3 showthat Caucasian recruiters showed a strong favorit-

ism for Caucasian applicants, whereas African American recruiters did not

distinguish between Caucasian and African American applicants. In short,

there was no support for Hypothesis 1 with regard to age or sex, but there was

support with regard to race for Caucasian recruiters.

As the offer decision criterion was dichotomous and the applicant assess-

ments were nested within recruiters, structural equations modeling was inap-

propriate for this data set (L. Williams, personal communication, November

8, 2002). Therefore, tests for mediation were performed following the proce-

dure presented by Baron and Kenny (1986) and by Kenny (1998). Specifi-

cally, four steps are needed to establish mediation. Step 1: Show that the ini-

tial variable is related to the outcome. Step 2: Showthat the initial variable is

related to the mediator. Step 3: Show that the mediator affects the outcome

variable, after controlling for the initial variables. Step 4: Determine whether

the relationship between the initial variable and the outcome variable

becomes nonsignificant (full mediation) or just smaller but still statistically

significant (partial mediation) after controlling for the mediator. Because

establishing mediation requires that all four steps be met, mediational tests

were only performed in those cases where Tables 3, 4, and 5 indicated signif-

icant demographic similarity effects on both an outcome and on at least one

proposed mediator. Consequently, no further tests were performed for age

similarity as Table 3 failed to provide support for the proposed direct effects.

For sex similarity, no mediational tests relating to offer decisions were per-

formed as Table 4 showed no significant direct effect between sex similarity

and this outcome. Finally, for race similarity, I did not perform mediational

tests for the effects of perceived similarityor interpersonal attractionas Table

5 showed that race similarity was not significantly related to either of these

criteria.

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 609

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

The second and third set of hypotheses proposed that the impact of demo-

graphic similarity on overall interview assessments and offer decisions was

mediated by perceived similarity and interpersonal attraction. In addition,

overall interview assessment was expected to mediate the relationship

between demographic similarity and offer decisions. Table 6 shows that the

relationship between race similarityand offer decision was completely medi-

ated by overall interviewassessments. Specifically, the relationship between

610 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

TABLE 3

Age Similarity Regressions

Overall

Perceived Interpersonal Interview Offer

Similarity Attraction Assessment Decision

R

2

F R

2

F R

2

F

2

Step 1: Recruiter dummy variables .44 4.03** .33 2.51** .29 2.04** 61.02*

Step 2: Resume quality .08 44.49** .09 39.62** .18 85.17** 8.46**

Step 3: Applicant age

Step 3: Recruiter age .00 .54 .01 1.33 .01 1.42 1.32

Step 4: Applicant age*

Step 4: Recruiter age .00 1.16 .00 .00 .00 .06 .90

Step 5: Applicant age squared

Step 5: Recruiter age squared .01 4.77* .00 .88 .01 2.30 .78

NOTE: The no. of dummy variables ranged from 47 to 49.

*p .05. **p .01. p .10.

TABLE 4

Sex Similarity Regressions

Overall

Perceived Interpersonal Interview Offer

Similarity Attraction Assessment Decision

R

2

F R

2

F R

2

F

2

Step 1: Recruiter dummy variables .44 4.03** .33 2.51** .29 2.04** 60.99*

Step 2: Resume quality .08 44.49** .09 39.61** .18 85.17** 8.46**

Step 3: Applicant sex

Step 3: Recruiter sex .00 .29 .01 1.60 .00 .35 1.95

Step 4: Applicant sex*

Step 4: Recruiter sex .01 3.46 .01 4.87* .01 5.62** .09

NOTE: Sex was effects coded (1/1) such that 1 = interactions with similar pairs and 1 = inter-

actions with dissimilar pairs. The no. of dummy variables ranged from 47 to 49.

*p .05. **p .01. p .10.

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

race similarity and offer decision was significant (p < .05), the relationships

between race similarity and perceived attitudinal similarity and between

perceived attitudinal similarity and offer decision were marginally signifi-

cant (p < .10), and, after controlling for interview assessment, the relation-

ship between race similarity and offer decision became nonsignificant. This

lent some limited support to Hypothesis 2b. As none of the other proposed

mediators between race similarity and the outcomes were significant, there

was no support for Hypothesis 2a with regard to race.

Table 6 also demonstrates that the relationship between recruiter-applicant

sex similarity and overall interview assessment was fully mediated by both

perceived similarity and interpersonal attraction and that the relationship

between sex similarity and interpersonal attraction was fully mediated by

perceived similarity. Specifically, sex similarity ( p < .05 in both cases) and

perceived attitudinal similarity ( p < .01 in both cases) were significantly

related to both interpersonal attraction and interview assessments, sex simi-

larity was marginally ( p <.10) related to perceived attitudinal similarity, and,

after controlling for perceived attitudinal similarity, the relationships

between sex similarity and both interpersonal attraction and overall inter-

view assessments became nonsignificant. In addition, the results of the sex

similarity mediational tests showthat interpersonal attraction partially medi-

ated the relationship between perceived similarity and overall interview

assessments, as evidenced by the fact that the relationships between per-

ceived attitudinal similarity and overall interviewassessments ( p < .05), per-

perceived similarity and interpersonal attraction ( p < .01), and interpersonal

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 611

TABLE 5

Race Similarity Regressions

Overall

Perceived Interpersonal Interview Offer

Similarity Attraction Assessment Decision

R

2

F R

2

F R

2

F

2

Step 1: Recruiter dummy variables .46 3.54** .37 2.41** .36 2.22** 51.96

Step 2: Resume quality .07 30.67** .09 30.60** .15 60.31** 3.99

Step 3: Applicant race

Step 3: Recruiter race .00 .90 .00 .11 .03 6.15** 8.32**

Step 4: Applicant race*

Step 4: Recruiter race .00 .38 .00 .48 .01 2.74 4.58*

NOTE: Only pairs with Caucasian or African American applicants are included in these analy-

ses. Race was effects coded (1/1) such that 1 = interactions with similar pairs and 1 = interac-

tions with dissimilar pairs. The no. of dummy variables ranged from 42 to 47.

*p .05. **p .01. p .10.

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

attraction and overall interview assessments ( p < .01) were all significant,

and the relationship between perceived similarity and overall interview

assessments remained significant ( p < .01) after controlling for the effects of

interpersonal attraction.

The negative coefficients in the first two columns of Table 6 and the pat-

terns depicted in Figure 2 suggest that the significant effects on the outcome

612 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

Sex Interactions for Perceived Similarity

3

3.05

3.1

3.15

3.2

3.25

3.3

3.35

3.4

Male Candidate Female Candidate

P

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

S

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

Male Recruiter

Female Recruiter

Sex Interactions for Attraction

3.3

3.35

3.4

3.45

3.5

3.55

3.6

3.65

Male Candidate Female Candidate

I

n

t

e

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

A

t

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

Male Recruiter

Female Recruiter

Sex Interactions for Overall Interview

Assessments

2.8

2.9

3

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

Male Candidate Female Candidate O

v

e

r

a

l

l

I

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

A

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

s

Male Recruiter

Female Recruiter

Figure 2: Plots of Sex Interactions

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

were the result of sex dissimilarity (Hypothesis 3) rather than sex similarity

(Hypothesis 2). An examination of Figure 2 and the separate coefficients for

male and female recruiters in Table 6 indicates that female recruiters made no

distinction between male and female applicants with regards to any of the

outcomes or mediators, whereas male recruiters perceived female applicants

more favorably than male applicants on overall interview assessments and

interpersonal attraction. These findings were inconsistent with the third

hypothesis, which proposed that female recruiters would show a preference

toward male applicants.

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 613

Race Interaction for Overall Interview

Assessments

2.5

2.6

2.7

2.8

2.9

3

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

Caucasian

Candidate

African-Amercian

Candidate

O

v

e

r

a

l

l

I

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

A

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

s

Caucasian

Recruiter

African-American

Recruiter

Race Interaction for Offer Decision

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

0.14

0.16

0.18

Caucasian

Candidate

African-Amercian

Candidate

P

r

o

b

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

o

f

O

f

f

e

r

Caucasian

Recruiter

African-American

Recruiter

Figure 3: Plots of Race Interactions

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

614

T

A

B

L

E

6

M

e

d

i

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

T

e

s

t

s

a

R

e

g

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

O

u

t

c

o

m

e

O

u

t

c

o

m

e

R

e

g

r

e

s

s

e

d

R

e

g

r

e

s

s

e

d

O

u

t

c

o

m

e

M

e

d

i

a

t

o

r

o

n

M

e

d

i

a

t

o

r

,

o

n

I

n

i

t

i

a

l

R

e

g

r

e

s

s

e

d

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

R

e

g

r

e

s

s

e

d

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

C

o

n

t

r

o

l

l

i

n

g

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

,

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

C

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

o

n

I

n

i

t

i

a

l

f

o

r

M

a

l

e

f

o

r

F

e

m

a

l

e

o

n

I

n

i

t

i

a

l

f

o

r

M

a

l

e

f

o

r

F

e

m

a

l

e

f

o

r

I

n

i

t

i

a

l

f

o

r

M

a

l

e

f

o

r

F

e

m

a

l

e

C

o

n

t

r

o

l

l

i

n

g

F

o

r

M

a

l

e

F

o

r

F

e

m

a

l

e

R

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

h

i

p

T

e

s

t

e

d

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

c

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

c

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

c

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

f

o

r

M

e

d

i

a

t

o

r

c

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

R

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

R

a

c

e

S

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

M

o

d

e

l

R

a

c

e

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

o

f

f

e

r

d

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

b

4

.

0

5

*

.

1

1

1

.

1

4

4

.

2

6

S

e

x

S

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

M

o

d

e

l

S

e

x

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

p

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

a

t

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

.

1

2

*

.

1

6

*

.

0

5

.

0

9

.

1

0

.

0

8

.

7

7

*

*

.

7

7

*

*

.

7

6

*

*

.

0

5

.

0

9

.

0

2

S

e

x

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

p

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

.

1

3

*

.

1

4

*

.

1

1

.

0

9

.

1

0

.

0

8

.

6

7

*

*

.

6

1

*

*

.

7

1

*

*

.

0

6

.

0

8

.

0

5

S

e

x

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

a

t

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

1

3

*

.

1

6

.

0

5

1

2

*

.

1

4

.

1

1

.

6

5

*

*

.

5

6

*

*

.

7

9

*

*

.

0

5

.

0

4

.

0

8

P

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

s

i

m

i

l

a

r

i

t

y

a

t

t

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

.

6

8

*

.

7

8

*

*

.

4

3

*

*

.

3

4

*

*

a

.

T

h

e

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

w

e

r

e

i

n

c

l

u

d

e

d

i

n

t

h

e

s

e

a

n

a

l

y

s

e

s

;

h

o

w

e

v

e

r

,

f

o

r

e

a

s

e

o

f

p

r

e

s

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

,

o

n

l

y

r

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

h

i

p

s

o

f

t

h

e

o

r

e

t

i

c

a

l

i

n

t

e

r

e

s

t

a

r

e

d

i

s

p

l

a

y

e

d

.

b

.

B

e

c

a

u

s

e

l

o

g

i

s

t

i

c

r

e

g

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

w

a

s

u

s

e

d

f

o

r

t

h

e

o

f

f

e

r

d

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

,

a

l

l

o

f

t

h

e

c

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

s

p

r

e

s

e

n

t

e

d

i

n

t

h

i

s

r

o

w

a

r

e

u

n

s

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

i

z

e

d

.

c

.

M

a

l

e

a

n

d

f

e

m

a

l

e

r

e

c

r

u

i

t

e

r

s

*

p

.

0

5

.

*

*

p

.

0

1

.

.

1

0

.

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

DISCUSSION

To summarize the results of this study, recruiter-applicant race similarity

had significant direct effects on overall interviewassessments and final offer

decisions, and recruiter-applicant sex dissimilarity had a significant direct

effect on overall interview assessments. Conversely, age similarity was not

related to either criterion. In addition, there was some evidence that the pro-

posed mediators intervened in these relationships. The relationship between

race similarity and offer decision was completely mediated by overall inter-

view assessments; the relationship between sex dissimilarity and overall

interview assessments was fully mediated by perceived similarity and inter-

personal attraction; the relationship between sex dissimilarity and interper-

sonal attraction was fully mediated by perceived attitudinal similarity; and

the relationship between perceived similarity and overall interview assess-

ments was partially mediated by interpersonal attraction. However, these

findings do not lend support to the notion that similarity-attraction underlies

the relationship between demographic similarity and selection outcomes.

CONTRIBUTIONS

This study addressed a number of limitations of prior research on rela-

tional demography. As very fewapplied studies have examined the impact of

relational demography on applicant selection, this study filled an empirical

gap in the literature. Although some prior selection studies have considered

either one or two measures of demographic similarity, the current study

included indices of relational age, race, and sex. Some authors (Graves &

Powell, 1996) have questioned whether findings relating to interview out-

comes apply to job-offer decisions. Because the present study included both

overall interview assessments and subsequent offer decisions, it addressed

this concern.

A number of researchers have suggested that the relationship between

demographic similarity and work outcomes is the result of the similarity-

attraction process and the self-continuity drive proposed by SIT (Jackson

et al., 1991; Lawrence, 1997; Tsui &OReilly, 1989). This study contributed

to the literature by testing whether the linkages proposed in Byrnes (1971)

similarity-attraction model mediated the impact of demographic similarity

on selection outcomes. However, the findings suggest that similarity-

attraction does not explain the relationship between demographic similarity

and selection outcomes.

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 615

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

EXPLANATION OF FINDINGS

Harrison et al.s (1998) findings suggested that in the context of inter-

views, where the recruiter has had little opportunity to assess similarity to the

applicant on deep-level traits, categorizations based on surface-level traits

are more meaningful. This study provides evidence that applicants who are

racially similar to recruiters receive more favorable interview assessments

and are more likely to receive subsequent offers than are applicants who are

racially dissimilar. That recruiter-applicant race similarity yielded results

that were more congruent with the first hypothesis than did age or sex simi-

larity and is consistent with the evidence that our preference for similar oth-

ers may be the result of having had limited exposure to dissimilar others

(Ravenson, 1989). Through family and other social experiences, recruiters

have presumably had greater exposure to others from different sex and age

categories. In contrast, their interactions with others of different races may

have been more limited, making race similaritya more salient social category

with which to identify (Ashforth &Mael, 1989; Tajfel &Turner, 1986). Fur-

thermore, that Caucasians demonstrated a stronger homophily bias than did

African Americans is consistent with the literature on the self-enhancement

drive. For example, Gaertner and Dovidio (2000) note that as high status

group members seek to maintain their status, members of these groups show

a greater tendency to overvalue the in-group than do members of low status

groups.

Another possible explanation for the small or nonsignificant age and sex

effects may reflect the types of jobs for which the applicants were interview-

ing. That is, several researchers (Goldberg et al., 2001; Heilman, 1983; Perry

& Finkelstein, 1999) have suggested that jobs are age-typed and gender-

typed and that these age- and gender-types dictate the extent to which an indi-

vidual may be seen as a good match for a particular job. Thus, fit with the job

type may have overshadowed fit with the recruiters characteristics. To test

the effect of job type, I created a five-category variable (information or com-

puter systems, finance or accounting, sales or marketing, management, and

engineering) based on the jobs that the recruiters indicated they were seeking

to fill, and I reran the analyses with job category as a control variable. How-

ever, the beta for this variable was 0 in all cases. Therefore, job type did not

appear to impact the findings of this study.

It is also worth noting that overall interview impressions fully mediated

the relationship between race similarity and offer decision. Despite the abun-

dance of support for Fishbein and Azjens (1975) theory of reasoned action

in other contexts, empirical evidence linking recruiters impressions (e.g.,

intentions) and offer decisions (e.g., behaviors) has been mixed. As with the

616 GROUP & ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

current study, Cable and Judge (1997) found a significant relationship

between recruiters postinterview impressions and subsequent offer deci-

sions. In contrast, Powell and Goulet (1996) found no evidence of such a

relationship. Perhaps labor market factors play a role in the relationship

between recruiters assessments and job offers. That is, it would be much

more difficult to find an effect during periods of high unemployment because

the base rate of offer decisions is lower. That the data in the Powell and

Goulet study were collected between 1990 and 1991 (G. Powell, personal

communication, December, 2000), during the height of a recession, whereas

data for the current study and that of Cable and Judge (1997; D. M. Cable,

personal communication, December, 2000) were collected in the mid-1990s,

when the economy was considerably stronger, lends some support to the idea

that labor market conditions may affect the nature of the relationship

between recruiters impressions and final offer decisions.

This study heeded Lawrences (1997) call to open the black box of organi-

zational demography to explore howand why demography affects work out-

comes. Although several researchers have suggested that the similarity-

attraction paradigm underlies the importance of demographic similarity on

organizational criteria (Jackson et al., 1991; Tsui et al., 1992; Tsui &

OReilly, 1989), I did not find evidence of such relationships. For race, none

of the proposed similarity-attraction mediational effects was significant.

That neither attitudinal similarity nor interpersonal attraction explained the

race similarity effects suggests that other processes may have been operat-

ing. Given the ample research suggesting that people have negative reactions

to African American applicants seeking white-collar jobs (cf. Stewart &

Perlow, 2001), racial prejudice may be a reasonable explanation.

I also failed to find gender similarity effects. Based on the abundance of

theoretical and empirical research (Ellemers et al., 1993; Ely, 1994, 1995;

Graves & Powell, 1995; Gutek, 1985; Sachdev & Bourhis, 1991) that sug-

gests that females seek to identify with males to maintain a positive identity, I

posited that female recruiters would favor male applicants but that male

recruiters would show no preference. In contrast, in the current study,

whereas female recruiters exhibited no preference toward applicants of

either sex, male recruiters evaluated female applicants higher than male

applicants on interpersonal attraction and overall interview assessments.

This contradicts the research on self-enhancement, which strongly suggests

that men would likely distance themselves from women to maintain their

higher status (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000). Note, however, that male recruit-

ers did not perceive either sex as more attitudinally similar to themselves. If

perceived attitudinal similarity does not explain male recruiters favorable

Goldberg / RELATIONAL DEMOGRAPHY 617

at Universiti Malaysia Sabah on October 9, 2014 gom.sagepub.com Downloaded from

assessments of female applicants interpersonal attractiveness and overall

interviewing effectiveness, then what does?

Although there is ample literature linking target similarity to oneself to

attraction (Byrne & Blalock, 1963; Byrne & Clore, 1970; Griffitt, 1969;

Newcomb, 1961), other researchers (Dalessio & Imada, 1984; LaPrelle,

Insko, Cooksey, & Graetz, 1993) contend that support for the similarity-

attraction paradigmmay be confounded with an ideal-attraction relationship

because for most people, their ideals are reasonably similar to their percep-

tions of themselves (Wetzel & Insko, 1984, p. 254). Furthermore, there is

evidence that the prototype of an ideal male target is different than that of an

ideal female target. Specifically, Freeman (1987) and Konrad and Cannings

(1997) note that males are idealized as success objects, whereas females are

idealized as sex objects. Consistent with this view, Sprecher (1989) found

that male participants considered physical attractiveness when assessing

their initial attraction to a female target, but female participants focused on

earnings potential when assessing their initial attraction to a male target. His

findings suggest that sex may signal which target attributes to emphasize in

evaluating another individual. To examine this possibility, using a 5-point,

single-item measure (the applicant had a pleasant physical appearance), I

performed post hoc analyses for the male recruiter subsample to determine

whether applicants appearance mediated the relationships between

applicant sex and interpersonal attractionand overall interviewassessments.

These results, which are presented in Table 7, provide support for partial

mediation. Consistent with Dalessio and Imadas (1984) findings, the analy-

ses reported here suggest that applicant-ideal matches may be more impor-

tant to recruiters than are applicant-self matches. Moreover, these findings

indicate that applicant sex may direct recruiters to attend to those characteris-

tics that are central to the ideal gender prototype for that applicant. This inter-

vening effect bridges the research that has shown that female stimuli are

more apt to invoke assessments of attractiveness than are male stimuli

(Larose, Tracy, & McKelvie, 1994) with the ample evidence that physical

attractiveness results in favorable outcomes (Drogosz & Levy, 1996;

Marlowe, Schneider, & Nelson, 1996).

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS

FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

This study addressed some of the gaps in the literature; however, it is not

without limitations. The demographic variables considered in the present

study were not evenly distributed. Although applicants were of a variety of

racial backgrounds, all recruiters (the respondents for this investigation)