Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Calin 2004 PDF

Încărcat de

Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Calin 2004 PDF

Încărcat de

Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

EXTENDED REPORT

Outcomes of a multicentre randomised clinical trial

of etanercept to treat ankylosing spondylitis

A Calin, B A C Dijkmans, P Emery, M Hakala, J Kalden, M Leirisalo-Repo, E M Mola,

C Salvarani, R Sanmart , J Sany, J Sibilia, J Sieper, S van der Linden, E Veys,

A M Appel, S Fatenejad

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

See end of article for

authors affiliations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Correspondence to:

Dr A Calin, Holmpatrick,

Weston Road, Bath BA1

2XU, UK; calinandrei@

hotmail.com

Accepted 23 May 2004

Published Online First

2 September 2004

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:15941600. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.020875

Objective: A double blind, randomised, placebo controlled study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of

etanercept to treat adult patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

Methods: Adult patients with AS at 14 European sites were randomly assigned to 25 mg injections of

etanercept or placebo twice weekly for 12 weeks. The primary efficacy end point was an improvement of

at least 20% in patient reported symptoms, based on the multicomponent Assessments in Ankylosing

Spondylitis (ASAS) response criteria (ASAS 20). Secondary end points included ASAS 50 and ASAS 70

responses and improved scores on individual components of ASAS, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis

Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), acute phase reactants, and spinal mobility tests. Safety was evaluated

during scheduled visits.

Results: Of 84 patients enrolled, 45 received etanercept and 39 received placebo. Significantly more

etanercept patients than placebo patients responded at the ASAS 20 level as early as week 2, and

sustained differences were evident up to week 12. Significantly more etanercept patients reported ASAS

50 responses at all times and ASAS 70 responses at weeks 2, 4, and 8; reported lower composite and

fatigue BASDAI scores; had lower acute phase reactant levels; and had improved spinal flexion.

Etanercept was well tolerated. Most adverse events were mild to moderate; the only between-group

difference was injection site reactions, which occurred significantly more often in etanercept patients.

Conclusions: Etanercept is a well tolerated and effective treatment for reducing clinical symptoms and signs

of AS.

A

nkylosing spondylitis (AS) is an underrecognised,

debilitating disease predominantly affecting the spine

that is characterised by axial skeletal ankylosis and

inflammation at the insertions of tendons. The prevalence of

AS is most clearly described in the white population where a

link to the HLA-B27 antigen is best defined, and is believed to

be around 0.5%, with estimates ranging from 0.1% to 1.1%.

1

Peripheral joints also may be affected. The disease occurs

three times more often in men than in women,

2

and onset

typically occurs between 20 and 40 years of age. Although

AS advances slowly, damage to the spine is progressive and

leads to pain, fatigue, stiffness, and functional impairment.

Patients with AS often have a restricted or poor quality of life

and may face a reduced life expectancy.

38

The socioeconomic

burden of their disease can be considerable, owing to work

disabilities and the use of healthcare/assistance resources,

and sometimes to the patients depressed mood or low social

functioning.

1 913

Current therapeutic options for AS, such as

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), offer tem-

porary pain relief but confer little if any clinical benefit on

spinal mobility. Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

(DMARDs), including methotrexate and sulfasalazine, may

benefit peripheral arthritis but do not appear to affect the

spinal involvement of AS.

1417

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) a (TNFa), is a proinflam-

matory cytokine that appears to have a key role in the

pathogenesis of AS.

12 1822

Etanercept is a fully human

recombinant protein, comprising two molecules of soluble

TNF receptor p75 and the crystallisable fragment component

of immunoglobulin G1, which specifically binds to and

neutralises TNFa.

23 24

Etanercept is effective in the treatment

of other TNF related diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis

(RA), juvenile chronic arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis

(PsA).

2527

More recently, a phase 2 clinical study has shown

that etanercept reduces disease activity in patients with

spondyloarthropathies, including reactive arthritis and

AS.

2831

Similar results have been reported with infliximab,

a chimeric monoclonal antibody against TNFa.

32 33

The current double blind, randomised, multicentre

European trial examined the efficacy of etanercept to treat

AS in adults, using the recently published criteria of an

international consortium of experts, the Assessments in

Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) Working Group.

34

Previous

etanercept trials in AS have been conducted at both North

American and European investigative sites. This study is the

first conducted exclusively at European centres. Because

there are potentially important differences between popula-

tions studied and in the way patients are treated in different

geographical locations, it was important to this study to

confirm the results of a multinational study of etanercept

that was conducted concurrently.

35

These trials are the first

studies performed with anti-TNF biological agents using the

ASAS response criteria as the primary end points.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASAS, Assessments in

Ankylosing Spondylitis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease

Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index;

CRP, C reactive protein; DMARDs, disease modifying antirheumatic

drugs; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis;

TNFa, tumour necrosis factor a; VAS, visual analogue scale

1594

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

PATI ENTS AND METHODS

Study desi gn

A double blind, randomised, placebo controlled study was

conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of etanercept

in the treatment of adult patients with active AS. The study

took place from March 2002 to August 2002 in 14 investiga-

tive centres in eight countries: Belgium, Finland, France,

Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and the United

Kingdom. All centres received approval from their indepen-

dent ethics committees, and all patients provided written

informed consent to participate. The study included a

screening period of up to 4 weeks, followed by a 12 week

treatment period in which patients received etanercept or

placebo. Efficacy and safety evaluations were performed at

weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12.

Pati ents

Patients aged 1870 years with active AS were eligible for the

study. AS was diagnosed using the modified New York

criteria.

36

Disease activity was measured using a set of visual

analogue scales (VAS) on which patients rated the severity

of their symptoms from 0 (none) to 100 (most severe) in

four symptom domains: (a) spinal inflammation; (b) back

pain; (c) patient global assessment of disease activity; and

(d) physical function. Active disease was diagnosed if the

patient had an average score >30 for spinal inflammation

and a score >30 on at least two of the other three domains.

Patients were excluded if they had complete ankylosis

(fusion) of the spine; previously used TNFa inhibitors,

including etanercept; used DMARDs other than hydroxy-

chloroquine, sulfasalazine, or methotrexate within 4 weeks

of baseline; used multiple NSAIDs; used .10 mg prednisone

daily; or changed doses of NSAIDs or prednisone within

2 weeks of baseline. Patients were permitted to continue

prestudy physiotherapy.

Patients who met eligibility criteria were stratified on the

basis of concomitant DMARD use at baseline and randomly

assigned to receive etanercept or placebo. The protocol did

not require screening for tuberculosis.

Study product

Based on previous clinical trials of etanercept in patients with

RA and PsA, a 25 mg dose delivered subcutaneously twice

weekly was selected for patients with AS. Patients self

administered the product and were given individual packages

containing injection supplies and instructions for storage and

use. To preserve the integrity of the blind study, placebo and

etanercept supplies were similar in appearance.

Effi cacy end poi nts

The clinical response to etanercept was evaluated chiefly on

the basis of response criteria recommended by the ASAS

Working Group,

34

which covered the same four domains used

in this study to assess disease activity at enrolmentthat is,

spinal inflammation, back pain, patient global assessment,

Table 1 Efficacy end points used to assess etanercept

I. ASAS Response Criteria: improvements of at least 20%, 50%, and 70%

in at least three of these four domains:

A. Spinal inflammation: composite of two items from BASDAIthat is,

1. Duration of morning stiffness

2. Intensity of morning stiffness

B. Total back pain and nocturnal back pain (combined)

C. Patient global assessment of health

D. Functional impairment: composite score of 10 items on BASFIthat is,

1. Putting on socks without aids

2. Picking up pen from floor

3. Reaching high shelf without aids

4. Getting up from an armless chair

5. Getting off floor from back

6. Standing unsupported for at least 10 minutes

7. Climbing 12 to 15 steps without aids

8. Looking over shoulder

9. Performing a demanding activity

10. Doing a full days activity

II. BASDAI scores

A. Daily activity composite score

B. Scores on six separate items

1. Fatigue

2. AS pain in necks, back, or hips

3. Pain in other joints

4. Discomfort in areas tender to touch or pressure

5. Duration of morning stiffness

6. Intensity of morning stiffness

III. Levels of acute phase reactants

A. C reactive protein (CRP)

B. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

IV. Spinal mobility scores

A. Forward flexion (Schobers test)

B. Chest expansion

C. Occiput to wall distance

ASAS, Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing

Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis

Functional Index.

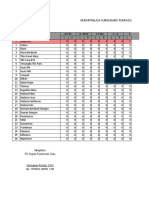

Table 2 Baseline demographic and descriptive characteristics

Characteristic

Total Placebo Etanercept

(n =84) (n =39) (n =45)

Age (years), mean (SD) 43.2 (10.6) 40.7 (11.4) 45.3 (9.5)*

Sex (men/women), % 79/21 77/23 80/20

Race (white/other), % 94/6 95/5 93/7

Disease duration (years), mean (SD) 12.5 (8.9) 9.7 (8.2) 15.0 (8.8)**

Concomitant use of DMARD, No (%) 32 (38) 16 (41) 16 (36)

Hydroxychloroquine 1 (1) 1 (3) 0

Methotrexate 11 (13) 5 (13) 6 (13)

Sulfasalazine 22 (26) 11 (28) 11 (24)

Concomitant use of oral NSAID, No (%) 73 (87) 33 (85) 40 (89)

Concomitant use of corticosteroid, No (%) 13 (15) 6 (15) 7 (16)

Mean scores on ASAS components:

Spinal inflammation 65.4 62.9 67.5

Nocturnal and total back pain 58.2 56.1 60.0

Patient global assessment 64.6 63.4 65.6

Functional impairment 58.8 57.2 60.2

Mean BASDAI scores overall 59.9 58.6 61.0

BASDAI scores ,40, No (%) 10 (12) 5 (13) 4 (9)

*p,0.05 versus placebo, by analysis of variance (ANOVA); **p,0.01 versus placebo, by ANOVA; one patient

in each group took more than one DMARD.

DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drug; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with etanercept 1595

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

and physical impairment. Spinal inflammation was scored as

the average of two VAS questions about the duration and

intensity of morning stiffness, taken from the previously

validated six item Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease

Activity Index (BASDAI).

37

Pain was scored as the average

of two VAS questions about total back pain and nocturnal

back pain. Patient global assessment was measured by VAS.

Functional impairment was assessed by the 10 item Bath

Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), a vali-

dated VAS based composite of functional ability in patients

with AS.

38

Table 1 shows details of the BASDAI and BASFI

indexes and other efficacy end points.

The primary efficacy end point was the percentage of ASAS

20 responders after 12 weeks of treatment. ASAS 20

responders were patients who reported improvements of at

least 20% and absolute improvement of at least 10 units in at

least three of the four symptom domains, with no worsening

in the remaining domain. Secondary end points included the

percentage of ASAS 20 responders at weeks 2, 4, and 8; the

percentage of patients improving 50% or more (ASAS 50) at

any visit; and the percentage improving 70% or more

(ASAS 70) at any visit. ASAS 50 and 70 responses also

required improvement in at least three domains and no

deterioration in the remaining domain. Other patient

reported end points consisted of symptom improvements in

individual ASAS domains and improvements on the compo-

site BASDAI and its individual components. Effects on acute

phase reactants were measured by tests for C reactive protein

(CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Effects on

spinal mobility were measured by Schobers test, chest

expansion, and occiput to wall distance.

Safet y anal yses

Patients were monitored for adverse events and abnormal

laboratory test results over the course of the study. Vital signs

were monitored, and standard haematology, serum chem-

istry, and urine analysis tests were evaluated. In addition,

blood samples were tested for antibody to etanercept at

baseline and at week 12, using an enzyme linked immuno-

sorbent assay (ELISA) modified from the method published

earlier.

39

Stati sti cs

Disease activity and safety analyses were based on the

intention to treat population and included all patients who

received at least one dose of the blinded test article. The

last observation carried forward technique was used to

handle missing data for continuous and ordinal end points.

Patients who withdrew from the study prematurely were

treated as non-responders at each assessment interval there-

after for ASAS and other patient reported responses. All

statistical tests were two sided. The Cochrane-Mantel-

Haenszel test, stratified by baseline DMARD use, was used

to evaluate efficacy differences between the etanercept and

placebo groups, and x

2

and Breslow-Day tests were used to

evaluate direct and interactive effects of DMARDs on ASAS

responses. For safety analyses, Fishers exact test was used to

compare the percentage of adverse events occurring in

etanercept and placebo treated groups. Based on a previous

trial, week 12 response rates of 35% in the placebo group and

75% in the etanercept group were expected. Assuming similar

response rates, this study design provided 90% power with 40

patients in each group.

RESULTS

Study obj ecti ve

This study was conducted to evaluated the safety and efficacy

of etanercept to treat adult patients with AS.

Pati ent recrui t ment and ret enti on

A total of 84 patients were enrolled in the study; 45 were

assigned to receive etanercept and 39 were assigned to

placebo. The average age of patients was 43.2 years. Most

participants were male (79%), and the majority were white

(94%). The treatment groups had similar baseline disease

activity scores and concomitant use of DMARDs, NSAIDs,

and corticosteroids. Demographic characteristics were largely

similar, except that etanercept patients were, on average,

5 years older than placebo patients, had had AS disease for

5 years longer (table 2), and also had significantly higher

baseline CRP levels (see table 4).

Two patients treated with etanercept discontinued the

study for non-safety reasons. The first patient discontinued

after a single dose of etanercept because he did not meet the

80

60

40

20

0

Weeks

Etanercept

A

Placebo

P

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

(

%

)

0 12

60.0

23.1

10 8

66.7

23.1

6 4

62.2

12.8

2

53.3

7.7

60

50

20

40

30

10

0

Weeks

Etanercept

B

Placebo

P

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

(

%

)

0 12

48.9

10.3

10 8

46.7

15.4

6 4

42.2

2.6

2

24.4

2.6

60

50

10

40

30

20

0

Weeks

Etanercept

C

Placebo

P

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

(

%

)

0 12

24.4

10.3

10 8

28.9

7.7

6 4

24.4

0.0

2

13.3

0.0

Figure 1 (A) Achievement of ASAS 20, by treatment group; (B)

achievement of ASAS 50, by treatment group; (C) achievement of ASAS

70, by treatment group.

1596 Calin, Dijkmans, Emery, et al

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

inclusion criterion of active disease, and the second patient

withdrew his consent 8 days after treatment was started.

Both patients were treated as non-responders at subsequent

times. The remaining 82 patients completed the study.

Effi cacy resul t s

Significantly more etanercept patients than placebo patients

(26 (60%) v 9 (23%); p,0.001; 95% confidence interval (CI)

17.4 to 56.4%) were ASAS 20 responders at week 12, the

primary efficacy end point. The primary end point was not

significantly affected by the concomitant use of DMARDs

(p=0.632), nor was there an interaction effect between

DMARDs and etanercept on ASAS 20 at week 12 (p =0.694).

Significant improvements in the etanercept group were

evident by week 2, the earliest assessment point, and were

sustained thereafter (fig 1A). There were also significantly

more responders in the etanercept group at the ASAS 50 level

at all visits (p,0.01) and at the ASAS 70 level at weeks 2, 4,

and 8 (p,0.05) (figs 1B and C). By week 12, nearly half of

the patients treated with etanercept improved 50% or more

on the ASAS criteria, and a quarter of them improved 70% or

more.

ASAS responses used in this study were based on the

average of total and nocturnal back pain. The ASAS Working

Group criteria, published after plans for this study were

completed, recommended using VAS for total back pain only.

Sensitivity analyses using total pain scores alone confirmed

nearly identical results to those reported here.

In addition to improved responses on the overall ASAS

criteria, etanercept patients significantly improved their

mean scores on the individual ASAS components (p,0.01

versus placebo). Scores of etanercept patients improved 43%

on both the spinal inflammation and back pain measures,

37% on patient global assessment of disease activity, and 35%

on the functional impairment index (compared with 16%,

6%, 13%, and 3% improvements, respectively, for placebo

patients; table 3). Although scores on individual components

of the BASFI are not provided in this paper, etanercept was

significantly more effective than placebo in improving nine of

10 types of functional abilities.

Scores on the BASDAI composite index and the BASDAI

fatigue component improved 44% among etanercept patients

(p,0.01 versus placebo). In addition, a post hoc analysis of

BASDAI responses showed that the percentage of etanercept

patients with BASDAI scores ,40 increased from 9% at

baseline to 71% at week 12 (fig 2).

Acute phase reactants, CRP and ESR, also significantly

decreased in etanercept patients (p,0.0001), with percentage

changes of 70% and 80%, respectively (table 4). Spinal

flexion, as measured by Schobers test, improved in etaner-

cept treated patients but not in placebo patients (p,0.01).

Other measures of spinal mobility also improved more in

etanercept patients, but the differences were not significant.

Patients in this trial had limited peripheral joint disease.

Numbers of swollen and tender joints were 2 and 6,

respectively, for the entire group. Given the paucity of this

information, no meaningful results on peripheral joint

disease were obtained.

Safet y resul t s

Etanercept treatment was generally well tolerated. Adverse

events were mostly mild to moderate, and there were no

discontinuations for safety reasons. Treatment-emergent

adverse events reported by 5% or more of patients in either

treatment group were generally similar (table 5). As in

previous studies of etanercept, injection site reactions

occurred significantly more often in etanercept patients

(33%) than in patients receiving placebo (15%, p,0.05). No

antibodies to etanercept were detected.

Table 3 Comparison of ASAS and BASDAI Scores before and after 12 weeks of

treatment

Response measure: assessment point

Placebo Etanercept

p Value* (n = 39) (n =45)

ASAS: Spinal inflammation

Baseline (mean) 62.9 67.5

Week 12 (% change) 52.6 (15.9) 35.6 (43.3) 0.003

ASAS: Nocturnal and total pain

Baseline (mean) 56.1 60.0

Week 12 (% change) 51.2 (6.2) 31.0 (43.1) 0.000

ASAS: Patient global assessment

Baseline (mean) 63.4 65.6

Week 12 (% change) 54.1 (12.6) 38.4 (37.0) 0.011

ASAS: Functional impairment (BASFI)

Baseline (mean) 57.2 60.2

Week 12 (% change) 53.9 (3.4) 39.6 (35.4) 0.000

BASDAI: Composite score

Baseline (mean) 58.6 61.0

Week 12 (% change) 50.1 (13.6) 33.8 (43.6) 0.001

BASDAI: Fatigue score

Baseline (mean) 59.0 68.2

Week 12 (% change) 54.8 (24.9) 38.4 (42.6) 0.000

*Differences in mean percentage change, baseline to week 12, by the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel test.

ASAS, Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASDAI, Bath

Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index.

80

60

40

20

10

70

50

30

0

Weeks

Etanercept

Placebo

P

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

(

%

)

0 12

71.1

25.6

10 8

62.2

30.8

6 4

55.6

20.5

2

44.4

15.4

Figure 2 Percentage of patients with BASDAI scores ,40.

Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with etanercept 1597

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

One serious adverse event was reported. An etanercept

treated patient with acute myocardial infarction underwent

angioplasty but continued in the study. The same patient

developed grade 3 abnormality of liver function test results at

the week 12 visit, which was considered to be related to

concomitant indometacin treatment. The abnormalities

resolved after indometacin was discontinued, and the patient

completed the study.

DI SCUSSI ON

AS is a chronic inflammatory disease, often leading to

permanent spinal damage, a considerable handicap, and a

poor quality of life. Current treatments for AS are inadequate

for most patients, especially treatments for axial skeletal

involvement.

In this 12 week study, twice weekly self administered

injections of 25 mg etanercept produced rapid, significant,

and sustained improvement in multiple clinical and biologi-

cal measures of AS, regardless of concomitant DMARD use.

Patient improvements were evident at the 2 week visit and

were sustained up to the end of the study at week 12.

Notably, the only differences between the groups at baseline

were that etanercept patients were on average 5 years older,

had had AS for 5 years longer than patients receiving

placebo, and had higher baseline CRP levels. Given the

magnitude of the etanercept treatment response in this

study, it is unlikely that these baseline differences affected

the results in any significant way. Furthermore, in light of

recent analyses indicating that older patients and patients

with longer disease duration are less likely to have a major

clinical response to TNFa inhibitors,

40 41

this groups demon-

strable response to etanercept is particularly encouraging.

The finding of multiple positive effects in this study of

European patients supports the results of two other efficacy

and safety studies of etanercept to treat AS. The first was a 16

week American study, which showed that etanercept was

efficacious in the treatment of many symptoms reported by

patients with AS, including pain, vitality, and physical

function.

28

The second was a 24 week multinational study

that was conducted concurrently with the present study and

included similar end points.

35

When the ASAS benchmarks of

20%, 50%, and 70% improvement were used, both the current

study and the 24 week study found that etanercept treatment

was significantly better than placebo, with robust improve-

ments occurring as early as week 2.

Treatment with etanercept also improved BASDAI scores;

by week 12, 71% of etanercept treated patients achieved

BASDAI scores ,40, which the ASAS Working Group

considers as the threshold value indicating a need for anti-

TNFa treatment.

42

Moreover, fatigue scores, which are felt to

be an important outcome in AS, improved significantly with

etanercept treatment.

43

Because fatigue is associated not only

with disease activity and functional ability but also with

patients global sense of wellbeing and mental health status,

44

improvement in this area may lead to a better quality of life

for patients with AS.

In the current study, CRP levels and ESR values signifi-

cantly decreased in patients taking etanercept, which may be

indicative of disease modification, not just symptomatic relief

of AS.

4548

Spinal mobility, as measured by Schobers test,

significantly improved in etanercept treated patients, which

suggests that damage caused by AS may not be permanent.

The lack of significant between-group differences in chest

expansion and occiput to wall distances at the end of

treatment may be due to the short duration of the study and/

or the relatively small number of patients enrolled. In the

24 week study mentioned earlier, which enrolled more

patients, all three spinal mobility measures significantly

improved with etanercept treatment.

35

Owing to the short

duration of this trial, the impressive therapeutic results must

interpreted with some caution. None the less, the relative

ineffectiveness of current treatments such as DMARDs and

Table 4 Comparison of acute phase reactants and spinal mobility values before and

after 12 weeks of treatment

Measurement: assessment point Placebo Etanercept p Value*

C reactive protein (mg/l) n =39 n =45

Baseline (median) 97 154

Week 12 (% change) 117 (0.0) 40 (69.5) 0.000

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/1st h) n =39 n =45

Baseline (median) 26.0 27.0

Week 12 (% change) 29.0 (0.0) 6.0 (79.6) 0.000

Schobers test of spinal flexion (cm) n =39 n =44

Baseline (mean) 2.8 2.2

Week 12 (% change) 2.7 (1.3) 2.7 (236.0) 0.009

Chest expansion (cm) n =39 n =44

Baseline (mean) 3.9 3.3

Week 12 (% change) 4.1 (29.0) 3.8 (229.9) 0.870

Occiput to wall distance ( cm) n =22` n =32`

Baseline (mean) 4.6 7.3

Week 12 (% change) 4.0 (7.2) 6.2 (12.5) 0.065

*Differences in average percentage change, baseline to week 12, by the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel test;

negative percentage change from baseline indicates improvement; `includes only patients who had a value

greater than zero at baseline.

Table 5 Number (%) of patients with treatment emergent

adverse events or infections (occurring in >5% of patients

in either treatment group)

Adverse event

Placebo Etanercept

p Value* (n =39) (n =45)

Injection site reactions 6 (15) 15 (33) 0.028

Haemorrhage, injection site 4 (10) 8 (18) 0.367

Headache 4 (10) 6 (13) 0.745

Nausea 4 (10) 3 (7) 0.699

Asthenia 1 (3) 5 (11) 0.209

Vertigo 3 (8) 0 0.096

Diarrhoea 2 (5) 2 (4) 1.000

Pruritus 2 (5) 2 (4) 1.000

Pain, abdomen 2 (5) 1 (2) 0.595

Paraesthesia 2 (5) 1 (2) 0.595

Arthralgia 2 (5) 0 0.213

Haemorrhage, gastrointestinal 2 (5) 0 0.213

Injury accidental 2 (5) 0 0.213

Pain, back 2 (5) 0 0.213

Throat irritation 2 (5) 0 0.213

*Difference in occurrence, by Fishers exact test.

1598 Calin, Dijkmans, Emery, et al

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

NSAIDs is underlined by the fact that etanercept treated

patients who continued to receive these treatments enjoyed

no apparent efficacious advantage over those who were not

receiving these drugs.

The efficacy results are also consistent with those reported

for infliximab

33 49

; however, no antibodies to etanercept were

found in this study. The lack of etanercept immunogenicity in

this trial might be explained by the trials brevity, and the

frequency of etanercept antibodies after long term treatment

in patients with AS is unknown. It is noteworthy, however,

that in etanercept trials of up to 2 years in patients with RA,

the level of etanercept antibody reactivity has been reported

to be around 3%.

50 51

Additionally, these results contrast with

the recent finding of a study of infliximab to treat Crohns

disease, in which 61% of patients produced antibodies to

infliximab after a mean of 3.9 infusions of 5 mg/kg over a

mean of 10 months. In the latter study, antibody concentra-

tions >8.0 mg/ml significantly reduced serum concentrations

of infliximab, which in turn significantly decreased the

duration of treatment response.

52

Etanercept was well tolerated in adult patients with AS.

Although approximately one third of patients had injection

site reactions, no serious infections occurred, and no patients

withdrew because of these reactions or other adverse events.

Etanercepts safety profile was similar to that seen in patients

with RA and PsA. Although pharmacokinetic measures from

the current study are not shown in this article, a separate

analysis of clearance and steady state trough concentrations

showed that etanercepts pharmacokinetic profile in patients

with AS was similar to that in patients with RA

53

; thus, it

appears that the disposition of etanercept is unaltered by the

AS disease state.

As noted above the socioeconomic burden of AS can be

considerable. Thus, the relatively higher cost of etanercept

treatment compared with less efficacious treatments should

be weighed against the costs of AS disease.

In summary, etanercept produced a rapid and sustained

reduction of the clinical signs and symptoms of AS. Given

these results, further investigation of longer term treatment

with etanercept is warranted to further define its therapeutic

utility. The use of imaging tools also is warranted to

investigate the effects of etanercept on spinal disease, and

such tests may shed light on whether etanercept can halt the

progression of AS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This trial was funded by Wyeth Research.

Ron Pedersen, an employee of Wyeth, is acknowledged for his study

design advice and statistical analysis. Susan Coyle, an employee of

Wyeth, is acknowledged for her writing support.

Authors affiliations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A Calin, Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Upper

Borough Walls, Bath BA1 1RL, UK

B A C Dijkmans, AZ Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

P Emery, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds, UK

M Hakala, Rheumatism Foundation Hospital, Heinola, Finland

J Kalden, University Hospital Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany

M Leirisalo-Repo, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

E M Mola, Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain

C Salvarani, Arcispedale S. Maria Nuova, Reggio Emilia, Italy

R Sanmart , Hospital Cl nic i Provincial, Barcelona, Spain

J Sany, Hopital Lapeyronie, Montpellier, France

J Sibilia, Hopital Hautepierre, Strasbourg, France

J Sieper, University Hospital Benjamin Franklin, Berlin, Germany

S van der Linden, Academisch Ziekenhuis, Maastricht, The Netherlands

E Veys, UZ Gent, Gent, Belgium

A M Appel, S Fatenejad, Wyeth Research, Collegeville, PA, USA

Presented in part at the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology in

Lisbon, Portugal, June 2003.

REFERENCES

1 Braun J, Sieper J. Therapy of ankylosing spondylitis and other

spondyloarthritides: established medical treatment, anti-TNF therapy and

other novel approaches. Arthritis Res 2002;4:30721.

2 Will R, Edmunds L, Elswood J, Calin A. Is there sexual inequality in ankylosing

spondylitis? A study of 498 women and 1202 men. J Rheumatol

1990;17:164952.

3 Kennedy LG, Edmunds L, Calin A. The natural history of ankylosing

spondylitis: does it burn out? J Rheumatol 1993;20:68892.

4 Ringsdal VS, Andreasen JJ. Ankylosing spondylitisexperience with a self

administered questionnaire: an analytical study. Ann Rheum Dis

1989;48:9247.

5 Ward MM. Health-related quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis: a survey of

175 patients. Arthritis Care Res 1999;12:24755.

6 Taylor AL, Balakrishnan C, Calin A. Reference centile charts for measures of

disease activity, functional impairment, and metrology in ankylosing

spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:111925.

7 Goodacre JA, Mander M, Dick WC. Patients with ankylosing spondylitis show

individual patterns of variation in disease activity. Br J Rheumatol

1991;30:3368.

8 Braun J, Pincus T. Mortality, course of disease, and prognosis of patients with

ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002;20:S1622.

9 Gran JT, Skomsvoll JF. The outcome of ankylosing spondylitis: a study of 100

patients. Br J Rheumatol 1997;36:76671.

10 Barlow JH, Wright CC, Williams B, Keat A. Work disability among people

with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res 2001;45:4249.

11 Ward MM. Functional disability predicts total costs in patients with ankylosing

spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:22331.

12 Grom AA, Murray KJ, Luyrink L, Emery H, Passo MH, Glass DN, et al. Patterns

of expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha, tumor necrosis factor beta, and

their receptors in synovia of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and

juvenile spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:170310.

13 Boonen A. Socioeconomic consequences of ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp

Rheumatol 2002;20:S236.

14 Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Weisman MH, Blackburn WD, Cush JJ, Cannon GW, et

al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of ankylosing

spondylitis: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Arthritis

Rheum 1996;39:200412.

15 Dougados M, van der Linden S, Leirisalo-Repo M, Huitfeldt B, Juhlin R, Veys E,

et al. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of spondylarthropathy: a randomized,

multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum

1995;38:61827.

16 Biasi D, Carletto A, Caramaschi P, Pacor ML, Maleknia T, Bambara LM.

Efficacy of methotrexate in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a three-

year open study. Clin Rheumatol 2000;19:11417.

17 Roychowdhury B, Bintley-Bagot S, Bulgen DY, Thompson RN, Tunn EJ,

Moots RJ. Is methotrexate effective in ankylosing spondylitis? Rheumatology

(Oxford) 2002;41:13302.

18 Maksymowych WP. Novel therapies in the treatment of spondyloarthritis.

Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2002;11:93746.

19 Toussirot E, Lafforgue P, Boucraut J, Despieds P, Schiano A, Bernard D, et al.

Serum levels of interleukin 1-beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, soluble

interleukin 2 receptor and soluble cd8 in seronegative spondylarthropathies.

Rheumatol Int 1994;13:17580.

20 Gratacos J, Collado A, Filella X, Sanmarti R, Canete J, Llena J, et al. Serum

cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta and IFN-gamma) in ankylosing

spondylitis: a close correlation between serum IL-6 and disease activity and

severity. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:92731.

21 Braun J, Bollow M, Neure L, Seipelt E, Seyrekbasan F, Herbst H, et al. Use of

immunohistologic and in situ hybridization techniques in the examination of

sacroiliac joint biopsy specimens from patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:499505.

22 Canete JD, Llena J, Collado A, Sanmarti R, Gaya A, Gratacos J, et al.

Comparative cytokine gene expression in synovial tissue of early rheumatoid

arthritis and seronegative spondylarthropathies. Br J Rheumatol

1997;36:3842.

23 Arend WP. The mode of action of cytokine inhibitors. J Rheumatol Suppl

2002;65:1621.

24 Fernandez-Botran R. Soluble cytokine receptors: novel immunotherapeutic

agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2000;9:497514.

25 Moreland LW, Schiff MS, Baumgartner SW, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM,

Bulpitt KJ, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized,

controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:47886.

26 Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, Cawkwell GD, Silverman ED, Nocton JJ, et al.

Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

N Engl J Med 2000;342:7639.

27 Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, VanderStoep A, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in

the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet

2000;356:38590.

28 Gorman JD, Sack KE, Davis JC Jr. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by

inhibition of tumor necrosis factor a. N Engl J Med 2002;346:134956.

29 Flores D, Marquez J, Garza M, Espinoza LR. Reactive arthritis: newer

developments. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2003;29:3759.

30 Brandt J, Khariouzov A, Listing J, Haibel H, Sorensen H, Grassnickel L, et al.

Six-month results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of etanercept

treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum

2003;48:166775.

31 Davis JC, Woolley JM. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes for

subjects with ankylosing spondylitis receiving etanercept therapy [abstract].

Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62(suppl I):252.

Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with etanercept 1599

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

32 Van den Bosch F, Kruithof E, Baeten D, Herssens A, de Keyser F, Mielants H,

et al. Randomized double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody

to tumor necrosis factor alpha (infliximab) versus placebo in active

spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:75565.

33 Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Golder W, et al. Treatment of

active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled

multicentre trial. Lancet 2002;359:118793.

34 Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, Felson DT, Dougados M. Ankylosing

spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement

in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:187686.

35 Davis JC Jr, van der Heijde D, Braun J, Dougados M, Cush J, Clegg DO, et al.

Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating

ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:32306.

36 van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for

ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria.

Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:3618.

37 Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new

approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath

Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol

1994;21:228691.

38 Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy LG, OHea J, Mallorie P, et al. A

new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the

development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol

1994;21:22815.

39 Moreland LW, Margolies G, Heck Jr LW, Saway A, Blosch C, Hanna R, et al.

Recombinant soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (p80) fusion protein:

toxicity and dose finding trial in refractory rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol

1996;23:1849.

40 Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, Sieper J. Prediction of a major

clinical response (BASDAI 50) to TNF alpha blockers in ankylosing spondylitis

[abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2003;62, (suppl I):242.

41 Davis J, Devries T. Predicting treatment response to biologic agents in

ankylosing spondylitis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62(suppl I):36.

42 Braun J, Pham T, Sieper J, Davis J, Van der Linden S, Dougados M, et al.

International ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti-tumour necrosis

factor agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis

2003;62:81724.

43 Dougados M, Woolley JM, Tsuji W. Etanercept reduces fatigue in subjects

with ankylosing spondylitis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis

2003;62(suppl I):244.

44 van Tubergen A, Coenen J, Landewe R, Spoorenberg A, Chorus A, Boonen A,

et al. Assessment of fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a

psychometric analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:816.

45 Maksymowych WP, Breban M, Braun J. Ankylosing spondylitis and current

disease-controlling agents: do they work? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol

2002;16:61930.

46 Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, OConnor P, Emery P. Efficacy of etanercept

in the treatment of the entheseal pathology in resistant spondylarthropathy: a

clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis Rheum

2001;44:211217.

47 Abuzakouk M, Feighery C, Jackson J. Tumour necrosis factor blocking agents:

a new therapeutic modality for inflammatory disorders. Br J Biomed Sci

2002;59:1739.

48 Braun J, Sieper J, Breban M, Collantes-Estevez E, Davis J, Inman R, et al. Anti-

tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy for ankylosing spondylitis: international

experience. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61(suppl III):iii5160.

49 Maksymowych WP, Jhangri GS, Lambert RG, Mallon C, Buenviaje H,

Pedrycz E, et al. Infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective

observational inception cohort analysis of efficacy and safety. J Rheumatol

2002;29:95965.

50 Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC,

et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early

rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:158693.

51 Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH,

et al. Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid

arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:144550.

52 Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, DHaens G, Carbonez A, et

al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab on

Crohns disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:6018.

53 Zhou H, Buckwalter M, Boni J, Wajdula J, Fatenejad S, Raible D, et al.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) of etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) patients

were similar to those in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients [abstract]. Ann

Rheum Dis 2003;62(suppl I):416.

1600 Calin, Dijkmans, Emery, et al

www.annrheumdis.com

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.020875

2, 2004

2004 63: 1594-1600 originally published online September Ann Rheum Dis

A Calin, B A C Dijkmans, P Emery, et al.

spondylitis

trial of etanercept to treat ankylosing

Outcomes of a multicentre randomised clinical

http://ard.bmj.com/content/63/12/1594.full.html

Updated information and services can be found at:

These include:

References

http://ard.bmj.com/content/63/12/1594.full.html#related-urls

Article cited in:

http://ard.bmj.com/content/63/12/1594.full.html#ref-list-1

This article cites 50 articles, 9 of which can be accessed free at:

service

Email alerting

box at the top right corner of the online article.

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

Collections

Topic

(2778 articles) Rheumatoid arthritis

(4233 articles) Musculoskeletal syndromes

(4326 articles) Immunology (including allergy)

(3959 articles) Degenerative joint disease

(3639 articles) Connective tissue disease

(631 articles) Calcium and bone

(362 articles) Ankylosing spondylitis

Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections

Notes

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To request permissions go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To order reprints go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

group.bmj.com on August 22, 2014 - Published by ard.bmj.com Downloaded from

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Rogers 1993Document4 paginiRogers 1993Nadia SaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ordi-Ros J, Et Al, 2017.Document8 paginiOrdi-Ros J, Et Al, 2017.Suhenri SiahaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- HarmacologyonlineDocument8 paginiHarmacologyonlineHisyam MuzakkiÎncă nu există evaluări

- PMC3580542 Ar4072Document12 paginiPMC3580542 Ar4072Juan Antonio Duque-TardifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Khannasharma 2017Document7 paginiKhannasharma 2017Imam IskandarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ankylosing SpondylitisDocument34 paginiAnkylosing SpondylitisAnumeha SrivastavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal UtamaDocument9 paginiJurnal UtamarekaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal UtamaDocument9 paginiJurnal UtamarekaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etanercept in Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Phase 2 TrialDocument8 paginiEtanercept in Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Phase 2 TrialGiuseppe AcanforaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 81635793Document13 pagini81635793Brock TernovÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S2772408522006408 MainDocument2 pagini1 s2.0 S2772408522006408 MainloloasbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lack of Anti-Drug Antibodies in Patients With Psoriasis Well-Controlled On Long-Term Treatment With Tumour Necrosis Factor InhibitorsDocument3 paginiLack of Anti-Drug Antibodies in Patients With Psoriasis Well-Controlled On Long-Term Treatment With Tumour Necrosis Factor InhibitorsDwi Tantri SPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aceclofenac Efficacy and Safety Vs DiclofenacDocument6 paginiAceclofenac Efficacy and Safety Vs DiclofenacpdelaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article 8Document4 paginiArticle 8umair muqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Results of Targeted Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy With Etanercept (ENBREL) in Patients With Advanced Heart FailureDocument12 paginiResults of Targeted Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy With Etanercept (ENBREL) in Patients With Advanced Heart FailureWidya SyahdilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- JRMS 18 43Document4 paginiJRMS 18 43Ricardo PietrobonÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Large Prospective Open-Label Multicent PDFDocument6 paginiA Large Prospective Open-Label Multicent PDFsyeda tahsin naharÎncă nu există evaluări

- JND200533Document8 paginiJND200533Rodrigo HolandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Green Light Exposure On Laurent MartinDocument13 paginiEvaluation of Green Light Exposure On Laurent MartinYunita Christiani BiyangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Club EdavaroneDocument5 paginiJournal Club EdavaroneJohn Christopher RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- MeduriDocument4 paginiMeduriSilvia Leticia BrunoÎncă nu există evaluări

- RR Franta 2018Document7 paginiRR Franta 2018SanzianaGogaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art 21054Document10 paginiArt 21054Ndhy Pharm HabibieÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Efficacy of 100 and 300 MG Gabapentin in The Treatment of Carpal Tunnel SyndromeDocument7 paginiThe Efficacy of 100 and 300 MG Gabapentin in The Treatment of Carpal Tunnel SyndromeSeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- KavanaughDocument11 paginiKavanaughluis moralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal AsthmaDocument11 paginiJurnal AsthmaNadira Juanti PratiwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comment: Lancet Infect Dis 2014Document2 paginiComment: Lancet Infect Dis 2014Tony TuestaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rheumatology 05Document6 paginiRheumatology 05C Bala DiwakeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs On Severity of Acute Pancreatitis and Pancreatic NecrosisDocument4 paginiThe Effect of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs On Severity of Acute Pancreatitis and Pancreatic NecrosisAracelyAcostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Olokizumab Versus Placebo or Adalimumab in Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument12 paginiOlokizumab Versus Placebo or Adalimumab in Rheumatoid ArthritisLee Foo WengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Step-Down Therapy From An Inhaled Steroid To Montelukast in Childhood AsthmaDocument7 paginiEvaluation of Step-Down Therapy From An Inhaled Steroid To Montelukast in Childhood AsthmaAriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper: NeuropsychiatryDocument11 paginiResearch Paper: NeuropsychiatryveerrajuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dupilumab AsthmaDocument11 paginiDupilumab AsthmaMr. LÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etanercept in Psoriasis: The Evidence of Its Therapeutic ImpactDocument12 paginiEtanercept in Psoriasis: The Evidence of Its Therapeutic ImpactArlha DebintaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jak Inhibitors As A New Modality For Treating Atopic Dermatitis: A Better Understanding of Its Efficacy and SafetyDocument22 paginiJak Inhibitors As A New Modality For Treating Atopic Dermatitis: A Better Understanding of Its Efficacy and SafetyIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etanercept Treatment For ChildrenDocument21 paginiEtanercept Treatment For ChildrenSitti Nurdiana DiauddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rheumathoid ArthritisDocument5 paginiRheumathoid ArthritisGheavita Chandra DewiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dose, Plasma Concentrations, (Sirdaludo) : Correlations Between and Action of TizanidineDocument6 paginiDose, Plasma Concentrations, (Sirdaludo) : Correlations Between and Action of TizanidineApriani MargastutieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Millimeter Wave Treatment of Diabetic Sensorymotor Polyneuropathy1Document6 paginiMillimeter Wave Treatment of Diabetic Sensorymotor Polyneuropathy1olgaremonÎncă nu există evaluări

- CTS 2Document10 paginiCTS 2Akuww WinwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15 MG With Piroxicam 20 MG in PatientsDocument4 pagini15 MG With Piroxicam 20 MG in PatientskwadwobrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- LY2439821, A Humanized Anti-Interleukin-17 Monoclonal Antibody, in The Treatment of Patients With Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument11 paginiLY2439821, A Humanized Anti-Interleukin-17 Monoclonal Antibody, in The Treatment of Patients With Rheumatoid ArthritisdechastraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal ReadingDocument6 paginiJournal ReadingInka Nadya TriayeshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Langley NEJM 2014Document13 paginiLangley NEJM 2014Andi MarsaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outcome of Double Blind Comparative Study of Sulfasalazine and Hydroxychloroquine in Early Undifferentiated Inflammatory ArthritisDocument6 paginiOutcome of Double Blind Comparative Study of Sulfasalazine and Hydroxychloroquine in Early Undifferentiated Inflammatory ArthritisIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 Article 924Document8 pagini2020 Article 924Luis Guillermo Buitrago BuitragoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhonda Byrne - El SecretoDocument8 paginiRhonda Byrne - El SecretoAlzeniraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weinblad 2001Document1 paginăWeinblad 2001remiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epi 12739Document8 paginiEpi 12739Juan Diego De La Cruz MiñanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PIIS0190962221020739Document2 paginiPIIS0190962221020739Roxanne KapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article Wjpps 1397637288Document11 paginiArticle Wjpps 1397637288Santosh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Menyhei 1994Document4 paginiMenyhei 1994Anett Pappné LeppÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vietnamese J Eujim 2020 101060Document7 paginiVietnamese J Eujim 2020 101060Diah AlyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- s1047965105001178 NSAIDDocument8 paginis1047965105001178 NSAIDIda LisniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2021 - Brazilian Recomendations For The Use of NSAID in Axial SpondyloarthritisDocument21 pagini2021 - Brazilian Recomendations For The Use of NSAID in Axial SpondyloarthritisGustavo ResendeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1059131121001692 MainDocument9 pagini1 s2.0 S1059131121001692 MainsoylahijadeunvampiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- I2211 4599 14 5 706Document7 paginiI2211 4599 14 5 706Jasper CubiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Small Fiber Neuropathy and Related Syndromes: Pain and NeurodegenerationDe la EverandSmall Fiber Neuropathy and Related Syndromes: Pain and NeurodegenerationSung-Tsang HsiehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ankylosing Spondylitis—Axial SpondyloarthritisDe la EverandAnkylosing Spondylitis—Axial SpondyloarthritisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arcuri 2021Document10 paginiArcuri 2021Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dimopoulos 2018Document48 paginiDimopoulos 2018Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quality of Life in HIV/AIDSDocument10 paginiQuality of Life in HIV/AIDSRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyDocument7 paginiCritical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Botta 2017Document12 paginiBotta 2017Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dimopoulos 2020Document8 paginiDimopoulos 2020Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giri 2020Document7 paginiGiri 2020Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basaran 2020Document5 paginiBasaran 2020Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acs Ca3 BookDocument69 paginiAcs Ca3 BookchrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cell Biology and Metabolism:: Colony-Stimulating Factor Stimulates Granulocyte-MacrophageDocument7 paginiCell Biology and Metabolism:: Colony-Stimulating Factor Stimulates Granulocyte-MacrophageRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perforation Risk and Intra-Uterine Devices: Results of The EURAS-IUD 5-Year Extension StudyDocument6 paginiPerforation Risk and Intra-Uterine Devices: Results of The EURAS-IUD 5-Year Extension StudyRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of Biologics and Oral Treatments For Plaque Psoriasis A Meta-AnalysisDocument12 paginiComparison of Biologics and Oral Treatments For Plaque Psoriasis A Meta-AnalysisRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yamamura 2019Document1 paginăYamamura 2019Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of Biologics and Oral Treatments For Plaque Psoriasis A Meta-AnalysisDocument12 paginiComparison of Biologics and Oral Treatments For Plaque Psoriasis A Meta-AnalysisRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weber 2016Document10 paginiWeber 2016Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Armstrong 2020 - Suppl.Document30 paginiArmstrong 2020 - Suppl.Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- FF PDFDocument473 paginiFF PDFR HariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yasmeen 2020Document16 paginiYasmeen 2020Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gane 2017Document1 paginăGane 2017Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warren 2019Document12 paginiWarren 2019Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gómez-García 2016Document10 paginiGómez-García 2016Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Very Severe Spinal Muscular Atrophy (Type 0) : A Report of Three CasesDocument4 paginiVery Severe Spinal Muscular Atrophy (Type 0) : A Report of Three CasesRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Burden of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Value-Based AnalysisDocument10 paginiThe Burden of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Value-Based AnalysisRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenawey 2014Document6 paginiKenawey 2014Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Broch 2012Document7 paginiBroch 2012Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noninvasive Cardiac Output Measurement: A New Tool in Heart FailureDocument3 paginiNoninvasive Cardiac Output Measurement: A New Tool in Heart FailureRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ameloot 2015Document8 paginiAmeloot 2015Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALBAR de Et Al 2012 ArchaeometryDocument15 paginiALBAR de Et Al 2012 ArchaeometryRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Botte 2006Document6 paginiBotte 2006Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lethaby Et Al-2013-The Cochrane LibraryDocument470 paginiLethaby Et Al-2013-The Cochrane LibraryRafaela Queiroz MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kursk State Medical University Department of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Exam Questions On Infectious Diseases Faculty: Medical Course: 6Document4 paginiKursk State Medical University Department of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Exam Questions On Infectious Diseases Faculty: Medical Course: 6Elephant ksmileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laporan Bulanan Rekapitulasi Surveilans Terpadu Penyakit (STP) Baru Di Puskesmas Dan Jejaringnya Puskesmas SoliuDocument37 paginiLaporan Bulanan Rekapitulasi Surveilans Terpadu Penyakit (STP) Baru Di Puskesmas Dan Jejaringnya Puskesmas SoliuVictoria YanersÎncă nu există evaluări

- GB Pet Health Certificate - Word FormatDocument9 paginiGB Pet Health Certificate - Word FormatFernanda SoaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- MD3150E Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Public Health Week 5Document35 paginiMD3150E Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Public Health Week 5Juma AwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 84Document38 paginiChapter 84Naimon Kumon KumonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Building Learning Commitment - Perdalin-Project HopeDocument18 paginiBuilding Learning Commitment - Perdalin-Project Hopesusy kusumawardaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- RRLDocument4 paginiRRLMUNDER OMAIRA NASRA D.Încă nu există evaluări

- Non-Hodgkin'S Lymphoma: Oliveros Francis!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Document48 paginiNon-Hodgkin'S Lymphoma: Oliveros Francis!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!francis00090Încă nu există evaluări

- Caso MicroDocument36 paginiCaso MicroFernando Román RubioÎncă nu există evaluări

- DM 2020-0351 HPVDocument9 paginiDM 2020-0351 HPVShardin Labawan-Juen,RNÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 Antibiogram ReportDocument17 pagini2018 Antibiogram ReportAkshat KishoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- DapusDocument5 paginiDapusoppinokioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults - Rapid Evidence ReviewDocument6 paginiCommunity-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults - Rapid Evidence ReviewpachomdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baby Acne: What Could Be Causing My Baby's Acne?Document15 paginiBaby Acne: What Could Be Causing My Baby's Acne?Flora Angeli PastoresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathogenesis Typhoid Fever PDFDocument7 paginiPathogenesis Typhoid Fever PDFAry Nahdiyani Amalia100% (1)

- Department of Haematology: Test Name Result Unit Bio. Ref. Range MethodDocument4 paginiDepartment of Haematology: Test Name Result Unit Bio. Ref. Range MethodSiddhartha GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communicable DiseasesDocument8 paginiCommunicable DiseasesKarla Fralala100% (1)

- 21 Test BankDocument17 pagini21 Test BankNaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pneumonia Dan TB ParuDocument55 paginiPneumonia Dan TB ParuNitya Manggala JayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Blepharitis LeafletDocument2 paginiPatient Blepharitis LeafletPrincess ErickaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 6300732772877075609Document131 pagini5 6300732772877075609Manoranjan sahuÎncă nu există evaluări

- v16 n3Document219 paginiv16 n3Mark ReinhardtÎncă nu există evaluări

- 204 Questions On MicrobiologyDocument54 pagini204 Questions On MicrobiologyMolly ThompsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heather Zwickey, PHD - Important Clarifications Regarding Covid-19 and Natural Medicine - Dispelling Myths and MisconceptionsDocument9 paginiHeather Zwickey, PHD - Important Clarifications Regarding Covid-19 and Natural Medicine - Dispelling Myths and Misconceptionstahuti696Încă nu există evaluări

- IRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008Document57 paginiIRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008shellyrahmaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tinea Fungal Infections - Hoja 1Document3 paginiTinea Fungal Infections - Hoja 1EVELYN MONSERRAT SAPIEN TOBONÎncă nu există evaluări

- FilariasisDocument11 paginiFilariasishahahahaaaaaaa100% (1)

- Girl Scouts of The Philippines PermitDocument1 paginăGirl Scouts of The Philippines Permitbrave29heartÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work Sheet - (Topic - Antibiotics)Document4 paginiWork Sheet - (Topic - Antibiotics)Jotaro kujoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unwell Child PosterDocument2 paginiUnwell Child PosterGabriella GriffithsÎncă nu există evaluări