Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

2014-10!24!17 - Corwin's Motion To Dismiss

Încărcat de

joeyjpeters0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

338 vizualizări21 paginiMichael CORWIN is an investigator, journalist, and political blogger. He is the executive director of Independent Source PAC. ISPAC investigates and exposes the activities of political candidates, office holders, and interest groups. The stated goal of ISPAC is to hold politicians and office holders accountable.

Descriere originală:

Titlu original

2014-10!24!17_Corwin's Motion to Dismiss

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentMichael CORWIN is an investigator, journalist, and political blogger. He is the executive director of Independent Source PAC. ISPAC investigates and exposes the activities of political candidates, office holders, and interest groups. The stated goal of ISPAC is to hold politicians and office holders accountable.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

338 vizualizări21 pagini2014-10!24!17 - Corwin's Motion To Dismiss

Încărcat de

joeyjpetersMichael CORWIN is an investigator, journalist, and political blogger. He is the executive director of Independent Source PAC. ISPAC investigates and exposes the activities of political candidates, office holders, and interest groups. The stated goal of ISPAC is to hold politicians and office holders accountable.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 21

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

CRYSTAL AMAYA, BRAD CATES,

BRIAN MOORE, AND KIM RONQUILLO,

Plaintiffs,

v. Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV

SAM BREGMAN, MICHAEL CORWIN,

J AMIE ESTRADA, ANISSA GALASSINI-

FORD, and J ASON LOREA,

Defendants.

MICHAEL CORWINS MOTION TO DISMISS

Defendant Michael Corwin, by and through his attorneys, Rothstein, Donatelli, Hughes,

Dahlstrom, Schoenburg & Bienvenu, LLP, hereby moves for dismissal of Plaintiffs Complaint

for Violations of the Federal Wiretap Act, the Stored Communications Act and Conspiracy to

Violate the Federal Wiretap Act (Doc. 1), as it relates to him, for failure to state a claim upon

which relief may be granted as authorized under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6).

INTRODUCTION

Mr. Corwin is, inter alia, an investigator, journalist, and political blogger. He is the

executive director of, and also an investigator and writer for, Independent Source PAC (ISPAC),

an organization that investigates and exposes the activities of political candidates, office holders,

and interest groups on its website, http://www.independentsourcepac.org/index.html, and

through printed newsletters. ISPACs mission is to disseminate source material for its news

bulletins and editorials by publicizing those documents, video and audio. The stated goal of

ISPAC is to hold politicians and office holders accountable to everyone, not just special interests.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 1 of 21

2

Although ISPAC operates as an independent entity, and is definitely a political organization, it

does not coordinate with any campaign, candidate, or party. ISPAC has, and continues to,

expose corruption in the Administration of Governor Susana Martinez, in particular, corruption

related to the Public Education Department (PED) and the Downs racetrack.

As a result of his political speech, supporters of the Martinez Administration have

engaged in a pattern of retaliatory actions against Mr. Corwin. The instant lawsuit is an epitome

of such retaliation. Plaintiffs Complaint, as it concerns Mr. Corwin, alleges the illegal use and

disclosure of information obtained from allegedly illegal interception of emails under the Federal

Wiretap Act, 18 U.S.C. 2510-2522 (FWA). Tellingly, the Complaint is virtually devoid of

facts specifically related to Mr. Corwin and provides no detail addressing how, in any fashion,

Mr. Corwin purportedly violated the FWA. See generally Doc. 1. Given the lack of specificity

in the Complaint, Mr. Corwin must speculate about Plaintiffs claims against him, and assumes

that the claims are based on Mr. Corwins publishing allegedly

1

stolen emails and providing

allegedly stolen emails that were not related to matters of public importance to the New Mexico

Attorney Generals (AG). The AG then released those emails to the Santa Fe Reporter in

response to an Inspection of Public Records Act request. Notwithstanding the bare bones

allegations set forth in the compliant, Plaintiffs fail to state a plausible claim against Mr. Corwin.

This shortcoming is fatal to Plaintiffs case, and therefore this action must be dismissed as to Mr.

Corwin for failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted.

1

At times in this motion, Mr. Corwin refers to allegedly illegally intercepted emails. Mr.

Corwin acknowledges that Defendant J amie Estrada has pled guilty to one count of Unlawful

Interception of Electronic Communications in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2511(1)(a). See Plea

Agreement (Doc. 79), United States v. Estrada, No. 13-cr-1877 WPJ (D.N.M. J une 16, 2014).

Accordingly, Mr. Corwins reference to the alleged nature of the interception, use, and

disclosure of the emails at issue in this case is meant to apply only to Mr. Corwin.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 2 of 21

3

BACKGROUND FACTS

This action arises from the allegedly illegal interception of emails between Governor

Susana Martinez, her staff, and various advisors from private (as opposed to public) email

accounts by Governor Martinezs former campaign manager, Mr. Estrada. Some of the emails

intercepted by Mr. Estrada were published by ISPAC and provided by Mr. Corwin to the media,

and to law enforcement, as part of ISPACs mission to expose potential public corruption or

other wrongdoing by those in office. Not only did Mr. Corwin provide particular emails to

outside media outlets and journalists, he also provided copies to the AG, as part of a complaint of

alleged misconduct on the part of the Governor and her staff, based in large part on the contents

of some of the subject email correspondence. In response to Mr. Corwins complaints, the AG

conducted an investigation into Mr. Corwins allegations of corruption and AG investigators

requested additional email documentation from Mr. Corwin, which he provided.

Mr. Corwins publishing of the emails, and provision of the emails to the AG, were in no

way extraordinary. Mr. Corwin has been reporting potential criminal conduct on the part of

Governor Martinez, members of her administration, as well as others, since November of 2011 to

the public and to law enforcement. The emails at issue here were part of those investigations.

The following is a chronology of Mr. Corwins investigative reporting and petitioning the

government for redress of grievances:

1. Mr. Corwin made his first request for an investigation into possible criminal activity

involved in the awarding of a lucrative state contract to the Downs of Albuquerque by

letter to the Office of the United States Attorneys on November 22, 2011. Kenneth

Gonzales acknowledged receipt of that letter on December 6, 2011, in correspondence to

Mr. Corwin, and stated that he was forwarding Mr. Corwins request for an investigation

to the FBI. Based on that information, Mr. Corwin sent, via facsimile, a letter to the FBI

on December 15, 2011, containing additional information revealed by his investigation.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 3 of 21

4

2. On J anuary 20, 2012, Mr. Corwin publicly released the first of two investigative reports

on the Downs contract, via the website for ISPAC, and in print. This report was

delivered directly to the FBI on J anuary 24, 2012.

3. On March 7, 2012, Mr. Corwin delivered another letter to the FBI, with additional

information concerning the contract at issue. All of these letters detailed the connections

between individuals and campaign contributions in connection with the award of the

billion-dollar contract.

4. On April 4, 2012, Mr. Corwin publicly released a second investigative report into this

potential corruption and criminal misconduct. On that same day, he requested that the

AG investigate the awarding of the contract. This report contained information gleaned

from emails obtained through public records requests, but not the emails at issue in this

case.

5. On J une 5, 2012, Mr. Corwin sent another letter to the FBI and the AG with additional

information gleaned from his investigation.

6. On J une 12, 2012, Mr. Corwin asked the AG to investigate possible corruption within the

PED. With a follow up letter on J une 13, 2012 regarding the Downs investigation, Mr.

Corwin notified the AG of the use of private email addresses in relation to PED business.

7. On J une 26, 2012, Mr. Corwin sent information on emails related to the Downs to both

the AG and the FBI. On the same day, he published emails pertaining to the Downs on

his website, and on J uly 2, 2012, he sent copies of the Downs emails to the FBI and AG.

These are the emails believed to be at issue in this case. They were provided to Mr.

Corwin by a confidential source.

8. The AG then requested copies of all the emails in Mr. Corwins possession, including

those of a private nature. Mr. Corwin forwarded the emails in his possession to the AG

on J uly 16, 2012. On J uly 19, 2012, the AG investigator requested that Mr. Corwin

obtain all the emails that Mr. Corwin could get from his confidential source. Mr. Corwin

requested the emails from his source, who then provided them. In turn, Mr. Corwin

provided those emails to the AG on J uly 23, 2012.

According to Plaintiffs, the emails that the confidential source provided to Mr. Corwin

were illegally intercepted by Mr. Estrada. In their Complaint, Plaintiffs vaguely suggest that Mr.

Corwin is somehow connected to Mr. Estrada. To the contrary, Mr. Corwin has met Mr. Estrada

only once. During that single meeting, the subject of the intercepted emails never surfaced. In

fact, Mr. Corwin did not receive the emails from Mr. Estrada, and Plaintiffs have not alleged that

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 4 of 21

5

he did. At the time Mr. Corwin obtained the emails upon which this case is grounded, he had no

knowledge whatsoever that they had been illegally obtained. More importantly, Plaintiffs have

not alleged that Mr. Corwin had any reason to believe that the emails had been illicitly acquired.

ARGUMENT

This Court may dismiss a complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief may be

granted. Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6). To survive a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6), a

plaintiff must nudge his claims across the line from conceivable to plausible. Ridge at Red

Hawk, L.L.C. v. Schneider, 493 F.3d 1174, 1177 (10th Cir. 2007) (quoting Bell Atl. Corp. v.

Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 570 (2007) (alterations omitted)). In deciding whether to dismiss a

complaint under Rule 12(b)(6), the Court is to assume the truth of the plaintiffs well-pleaded

factual allegations and view them in the light most favorable to the plaintiff. Id.

Legal conclusions, however, are handled much differently. Unlike factual allegations,

legal conclusions are not assumed to be correct unless they are supported by the necessary

factual allegations. Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 679 (2009). Accordingly, a complaint

must contain sufficient factual matter, accepted as true, to state a claim to relief that is plausible

on its face. Id. at 678 (quoting Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555). The Plaintiffs carry an obligation

to provide a sufficient factual foundation to warrant their entitle[ment] to relief. Twombly,

550 U.S. at 555. That burden requires more than labels and conclusions, and a formulaic

recitation of the elements of a cause of action will not do. Id. In ruling on a Rule 12(b)(6)

motion, the Court may consider documents incorporated by reference in the complaint;

documents referred to in and central to the complaint, when no party disputes its authenticity;

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 5 of 21

6

and matters of which a court may take judicial notice. Berneike v. CitiMortgage, Inc., 708 F.3d

1141, 1146 (10th Cir. 2013) (internal quotation omitted).

I. Plaintiffs Failure to Adequately Allege a Factual Case Under the FWA Is Fatal to

the Cause of Action Alleged Against Mr. Corwin.

The factual allegations supporting Plaintiffs FWA claim against Mr. Corwin fall far

short of what is required to survive this motion to dismiss. Plaintiffs have sued Mr. Corwin for

an alleged illegal disclosure and/or use of Plaintiffs electronic communications under 18 U.S.C.

2511(1)(c)-(d) and 2520. See Doc. 1 at 15-16, 64-75 (Count Two).

2

Section 2511(1)

states that:

any person who--

(c) intentionally discloses, or endeavors to disclose, to any other person the

contents of any wire, oral, or electronic communication, knowing or having

reason to know that the information was obtained through the interception of a

wire, oral, or electronic communication in violation of this subsection;

(d) intentionally uses, or endeavors to use, the contents of any wire, oral, or

electronic communication, knowing or having reason to know that the

information was obtained through the interception of a wire, oral, or electronic

communication in violation of this subsection; or

shall be punished as provided in subsection (4) or shall be subject to suit as

provided in subsection (5).

Section 2520 provides the civil remedy for any violation of 2511(1). Because Plaintiffs have

not and ethically cannot plead facts that satisfy the legal standard set forth under 18 U.S.C.

2511(1)facts that would establish that Mr. Corwin knew or had reason to know that the emails

2

Plaintiffs do not allege that Mr. Corwin participated in, knew about, or was remotely aware that

the emails were illegally intercepted by Estrada. See Doc. 1 at 4-10 (factual allegations

regarding the interception of the emails), 14-15 (Count One, brought against Mr. Estrada only,

for interception of the emails).

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 6 of 21

7

at issue were obtained through the interception of a communicationtheir claims against Mr.

Corwin must be dismissed.

In general, liability under 2511(1) requires that a plaintiff prove intentional conduct.

Thompson v. Dulaney, 970 F.2d 744, 749 (10th Cir. 1992). Liability under subsections (c) and

(d) of the statute, however, requires a plaintiff to prove more than is required for liability for

interception of communications under subsections (a) and (b). Id. To establish liability for use

and disclosure, in addition to intentional conduct, a plaintiff must prove that the defendant knew

that 1) the information used or disclosed came from an intercepted communication, and 2)

sufficient facts concerning the circumstances of the interception such that the defendant could,

with presumed knowledge of the law, determine that the interception was prohibited. Id. Mere

knowledge that the information came from an intercepted communication is not enough.

Thompson v. Dulaney, 838 F. Supp. 1535, 1542 (D. Utah 1993). To prevail on a use or

disclosure claim, the Plaintiffs need to allege sufficient facts that would enable an inference to

be drawn that the defendant knew or should have known that the wiretap was an illegal one. Id.

The claim set forth here includes an unlawful use or disclosure under 2511(1)(c)-(d) that has a

significant mens rea element on top of the use or disclosure requirement. Zinna v. Cook, 428 F.

Appx 838, 840 (10th Cir. 2011) (citing Thompson, 970 F.2d at 748-49).

Of Plaintiffs 92-paragrah Complaint, only five paragraphs relate specifically to Mr.

Corwins alleged involvement with the emails at issue here. Three of those paragraphs simply

allege that Mr. Corwin published one of the intercepted emails and disclosed other intercepted

emails to the AG and others. See Doc. 1 at 13, 53-54. The remaining two paragraphs, the

paragraphs that attempt to establish a violation of 2511(1), allege:

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 7 of 21

8

69. Defendants Loera, Bregman, Corwin, and Galassini-Ford intentionally

disclosed and/or used Plaintiffs stolen electronic communications.

70. Based on the communications between and among the various Defendants

and the actions of the various Defendants, as described herein, and the

contents of the emails, Defendants Loera, Bregman, Corwin, and

Galassini-Ford knew, or should have known, or had reason to know that

any electronic communications that they received from any of the other

Defendants, or any other individual that related to the @susana2010.com

email accounts, were obtained through the wrongful and illegal

interception of electronic communications.

Id. at 15-16. These allegations are legal conclusions without viable factual support and are

silent as to any particulars regarding Plaintiffs actual FWA claim against Mr. Corwin.

Decuyper v. Flinn, No. 3:13-0850, 2014 WL 4272720 at *2-3 (M.D. Tenn. Aug. 29, 2014).

Instead, they merely track the language of 2511(1)(c)-(d), and represent nothing more than a

formulaic recitation of the elements of a cause of action under the FWA. Twombly, 550 U.S. at

555. As published federal cases easily demonstrate, Plaintiffs have not made a plausible

showing of [their] entitlement to relief under the FWA. Decuyper, 2014 WL 4272720 at *3

(recommending that defendants motion to dismiss be granted where plaintiffs FWA claim

lacked detail and merely tracked the language of the statute).

Where a claim for violation of the FWA has no factual basis and is supported only by

conclusory statements, it must be dismissed as a matter of law. See Zinna, 428 F. Appx at 840

(granting summary judgment to defendants where plaintiffs claims under 2511(1) were based

only on speculation, conjecture, and general assertion and supposition devoid of supporting

citation); Thompson, 838 F. Supp. at 1546-47 (granting summary judgment on factually

unsupported FWA claims against certain defendants). Plaintiffs Complaint utterly fails to allege

a plausible FWA claim against Mr. Corwin. Indeed, Mr. Corwin had no reason to know that the

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 8 of 21

9

emails were obtained by a prohibited interception of communications. He had no knowledge of

Mr. Estradas conduct, or that Mr. Estrada had illicitly intercepted the emails by prohibited

means. Without such factual proof, Plaintiffs FWA claim against Mr. Corwin fails as a matter

of law. See McCann v. Iroquis Meml Hosp., 622 F.3d 745, 753-54 (7th Cir. 2010) (holding that

defendants who had no reason to think that the interception of a conversation violated the FWA

could not be liable under 2511(1)(c) or (d) of the FWA); Hamed v. Pfeifer, 647 N.E.2d 669,

671 (Ind. Ct. App. 1995) (same).

II. Plaintiffs FWA Claim Against Mr. Corwin Fails Because Mr. Corwins Receipt,

Disclosure, and Use of the Emails Are Protected By the First Amendment.

Even if Plaintiffs could state a FWA disclosure and use claim against Mr. Corwin, as

plead, any such claim would fail under the protections provided by the First Amendment to the

Constitution. The only emails made public by Mr. Corwin were those that dealt with matters of

public concern. Those emails should have never been on private email accounts in the first place

because they discussed matters of public import by government officials who were required to

use formal government email accounts to distribute that kind of communication. Mr. Corwin

also provided emails of public importance to the AG and FBI in connection with his requests to

those agencies to investigate what he believed to be public corruption. Other emails of a private

nature, including Plaintiffs emails, were provided by Mr. Corwin only to the AG after that office

repeatedly requested that he provide a copy of all of the emails in question, not just those he had

published due to their public nature. Mr. Corwin made no other disclosures of the emails. The

disclosures that he did make are protected by the First Amendment. Accordingly, Plaintiffs

FWA claims against Mr. Corwin fail for failure to state a plausible claim to relief.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 9 of 21

10

A. The FWA Is Unconstitutional as Applied to Mr. Corwins Disclosure of

Information of Public Concern.

Assuming arguendo that the emails at issue here were illegally intercepted,

3

Plaintiffs

FWA claim against Mr. Corwin still fails because application of the FWA to Mr. Corwins

disclosures of the emails violates the First Amendment. The basic purpose of the FWA is to

protect the privacy of communications. Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514, 526 (2001).

However, because the FWAs naked prohibition against disclosures is fairly characterized as a

regulation of pure speech, id., application of the FWA is subject to intermediate scrutiny. Id. at

521. In Bartnicki, the Supreme Court held that application of the FWA against the defendants

violated their free speech rights because the illegally intercepted communication concerned a

matter of public importance and they had not been involved in the interception. See id. at 518,

534-35. The same is true here.

As discussed in Bartnicki, Mr. Corwins disclosures of the illegally intercepted emails are

distinguishable from most cases that arise under 2511(1) for three reasons. See id. at 525.

First, even under Plaintiffs rendition of the facts, Mr. Corwin played no part in the illegal

interception. Id.; see also supra note 1. Second, Mr. Corwins access to the information [in

the emails] was obtained lawfully, even though the information itself was intercepted [allegedly]

unlawfully by someone else. Bartnicki, 532 U.S. at 525. Mr. Corwin received the emails from

a confidential source. He neither received the emails from Mr. Estrada nor did he have any

reason to believe that either his source or Mr. Estrada had obtained the emails illegally. Thus,

3

Mr. Corwin disputes that the emails at issue were illegally intercepted within the meaning of

the FWA. See Steve Jackson Games, Inc. v. U.S. Secret Serv., 36 F.3d 457, 462-64 (5th Cir.

1994) (explaining that Congress did not intend for intercept under the FWA to apply to email

under most circumstances, making interception of emails under 2511(1) virtually

impossible).

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 10 of 21

11

Mr. Corwins access to the emails and their content was lawful. Finally, the emails were

newsworthy. Id. They showed apparent violations of the law and collusion on the Downs

contract, which undoubtedly were matters of public concern. Moreover, the very fact of the

emails themselves was newsworthy because they exposed the official use of unofficial email

accounts, communications that were, by their very nature, designed to prevent present and future

scrutiny of official communications involving public matters. Under the circumstances

presented here, the interests served by 2511(1) do not justify restricting Mr. Corwins First

Amendment speech.

The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly held that if a newspaper lawfully

obtains truthful information about a matter of public importance then state officials may not

constitutionally punish publication of the information, absent a need . . . of the highest order.

Id. at 527-28 (internal quotation omitted) (citing cases). In fact, the Supreme Court has held that

the press

4

has a constitutional right to publish information of great public concern even when it is

obtained from documents stolen from a third party. See id. at 528 (citing New York Times Co. v.

United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) (per curiam)). Gathering information about government

officials in a form that can readily be disseminated to others serves a cardinal First

Amendment interest in protecting and promoting the free discussion of governmental

affairs Glik v. Cunniffe, 655 F.3d 78, 79-81 (1st Cir. 2011 (quoting Mills v. Alabama, 384

4

Bloggers such as Mr. Corwin are no different than traditional journalists for purposes of First

Amendment protection. Cf. von Bulow by Auersperg v. von Bulow, 811 F.2d 136, 143 (2d Cir.

1987); Silkwood v. KerrMcGee Corp., 563 F.2d 433, 437 (10th Cir. 1977); Protecting the New

Media: Application of the Journalists Privilege to Bloggers, 120 Harv. L. Rev. 996, 998 (2007);

Bloggers as Newsmen: Expanding the Testimonial Privilege, 88 B.U. L. Rev. 1075 (October

2008).

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 11 of 21

12

U.S. 214, 218 (1966)). Thus, Mr. Corwin cannot be punished through this lawsuit for publishing

and otherwise disclosing information of public importance gleaned from the emails even if he

had known of their illicit provenance. Indeed, it would be quite remarkable to hold that speech

by a law-abiding possessor of information [Mr. Corwin] can be suppressed in order to deter

conduct by a non-law-abiding third party [allegedly Mr. Estrada]. Bartnicki, 532 U.S. at 529-30

(holding that prohibitions against disclosure do not reduce illegal interceptions of

communications).

Any privacy concerns implicated by Mr. Corwins public disclosures of the emails at

issue here give way when balanced against the interest in publishing matters of public

importance. In disclosing information from the allegedly illegally intercepted emails, Mr.

Corwin was reporting and editorializing on issues of public concern. The attendant loss of

privacy suffered by Plaintiffs and others is outweighed by freedom of speech and expression

under the First Amendment. See id. at 534-35. As noted by the Supreme Court, a strangers

illegal conduct does not suffice to remove the First Amendment shield from speech about a

matter of public concern. Id. at 535. Accordingly, Mr. Corwins actions are protected speech

and cannot serve as the basis for a viable claim under the FWA.

B. Mr. Corwins Constitutional Right to Petition for Redress Protects His Use

and Disclosure of Information of Private Concern.

To the extent that Mr. Corwin used or disclosed information that was not a matter of

public importance, his actions are protected by the First Amendment because his disclosure of

private emails was made only to the AG in connection with petitioning that office to conduct an

investigation into what he believed to be corruption in the Martinez Administration. Mr. Corwin

never published private emails on his website or provided them to anyone except the AGs

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 12 of 21

13

investigator at the explicit request of the AG. Such actions are protected by Mr. Corwins First

Amendment right to petition the government for redress.

The First Amendment states: Congress shall make no law respecting . . . the right of the

people . . . to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. U.S. Const. amend I. [A]

private citizen exercises a constitutionally protected First Amendment right anytime he or she

petitions the government for redress. Van Deelen v. Johnson, 497 F.3d 1151, 1156 (10th Cir.

2007). Under the right to petition for redress, a citizen has immunity from suit so long as the

citizens actions are directed toward influencing governmental action. Sierra Club v. Butz, 349

F. Supp. 934, 937 (9th Cir. 1972) (explaining that the Supreme Court has determined that First

Amendment guarantees are a defense to invasion of privacy claims) (collecting cases).

[L]iability can be imposed for activities ostensibly consisting of petitioning the government for

redress of grievances only if the petitioning is a sham, and the real purpose is not to obtain

governmental action, but to otherwise injure the plaintiff. Id. at 939; see also Cardtoons, L.C.

v. Major League Baseball Players Assn, 208 F.3d 885, 889 (10th Cir. 2000) (discussing

immunity from suit arising from the right to petition). Stated differently, liability can never be

imposed upon a party for damage caused by government action he induced. Sierra Club v.

Butz, 349 F. Supp. at 939. The facts here establish that Mr. Corwin only disclosed all of the

emails to the AG after he had complained about conduct that he legitimately believed to be

illegal, and the AG requested everything that he could obtain. His conduct, precipitated by

government action, is squarely protected by the First Amendments right to petition the

government for redress.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 13 of 21

14

On J une 12, 2012, Mr. Corwin asked the AG to investigate the actions of the PED. With

a follow up letter on J une 13, 2012 regarding the Downs investigation that Mr. Corwin had

previously asked the AG to conduct and that was already under way, Mr. Corwin notified the AG

of the use of private email addresses in relation to PED business. On J une 26, 2012, Mr. Corwin

sent information on emails related to the Downs to both the AG and the FBI. On the same day,

he published emails pertaining to the Downs on his website, and on J uly 2, 2012, he sent copies

of the Downs emails to the FBI and AG. Thereafter, the AG began requesting copies of all the

emails in Mr. Corwins possession, including those of a private nature. Mr. Corwin sent those to

the AG on J uly 16, 2012. On J uly 19, 2012, the AG investigator requested that Mr. Corwin

obtain all the emails that Mr. Corwin could get from his confidential source. Mr. Corwin

requested the emails from his source, who willingly disclosed them. In turn, Mr. Corwin

provided the emails to the AG on J uly 23, 2012.

Mr. Corwins conduct in disclosing emails of an arguably private nature was done in

response to a direct request from the AG, and only after Mr. Corwin had legitimately petitioned

the AG to investigate unlawful activity. It is not illegal for a citizen to report information to law

enforcement. See Meyer v. Bd. of Cnty. Commrs of Harper Cnty., 482 F.3d 1232, 1243 (10th

Cir. 2007) (attempt to report alleged criminal offense was conduct protected by the First

Amendment). To the extent Plaintiffs emails were allegedly disclosed by Mr. Corwin (the

Complaint contains no allegations on that point, see generally Doc. 1), they were disclosed only

to the AG. The fact that the AG later released the same emails to the Santa Fe Reporter in

December 2012 cannot be attributable to Mr. Corwin. Mr. Corwin cannot be held liable for such

government conduct as he had disclosed the emails to the AG in connection with his

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 14 of 21

15

constitutional right to petition the government. See, e.g., Sierra Club, 349 F. Supp. at 939

(dismissing defendants counterclaim where the only allegations supporting the claims were that

the plaintiffs by various acts induced or sought to induce a department of the federal

government to take certain actions).

III. Plaintiffs Fail to Adequately Allege a Claim Against Mr. Corwin for Conspiracy to

Violate the FWA.

Plaintiffs also have sued Mr. Corwin for alleged conspiracy to violate 2511(1) of the

FWA. See Doc. 1 at 16-17, 76-81 (Count Two). Like their claim for violation of 2511(1),

Plaintiffs conspiracy claim against Mr. Corwin should be dismissed because Plaintiffs have not

and ethically cannot plead facts adequate to allege a plausible claim for conspiracy.

In order to plead a conspiracy claim, a plaintiff must allege, either by direct or

circumstantial evidence, a meeting of the minds or agreement among the defendants. Salehpoor

v. Shahinpoor, 358 F.3d 782, 789 (10th Cir. 2004) (internal quotation omitted). A bare

assertion of conspiracy will not suffice. Twombly, 550 U.S. at 556. Conspiracy claims require

evidence from which it can reasonably be inferred that the alleged conspirators agreed to act in

concertand pursuing compatible, even parallel, aims is not enough to warrant that inference.

Zinna, 428 F. Appx at 840. Plaintiffs allegation of conspiracy does not come within the

universe of factually acceptable pleading requirements that would survive a motion to dismiss.

The single paragraph in Plaintiffs Complaint that attempts to establish a conspiracy

states:

78. Defendants agreed, conspired, reached a common understanding, and had

the common purpose to unlawfully and without authorization intercept, access,

disclose, and/or use electronic communications intended for Plaintiffs.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 15 of 21

16

Doc. 1 at 17. The complaints conclusory, factually unsupported, and formulaic allegation is, as

discussed above, insufficient to state a valid claim. See Salehpoor, 358 F.3d at 789 (conspiracy

claim was appropriately dismissed where plaintiff failed to set forth evidence of an agreement

and concerted action on the part of the [defendants] (emphasis added)). It provides no factual

detail about the who, when, where, why, or how the alleged conspiracy was hatched. Instead, the

allegation set forth in 78 is a pure legal conclusion, a simple recitation of the elements of

conspiracy. Rank speculation and conjecture about relationships and agreements among

defendants is not enough to support a claim for conspiracy to violate 18 U.S.C. 2511(1) of the

FWA. See Zinna, 428 F. Appx at 840 (affirming summary judgment). In short, nothing in

Plaintiffs Complaint alleges a plausible or legally viable conspiracy claim. For that reason, the

conspiracy charge against Mr. Corwin in Plaintiffs Complaint should be dismissed as a matter

of law. See Twombly, 550 U.S. at 569 (dismissing plaintiffs conspiracy complaint for failure to

state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face); Thompson, 970 F.2d at 750 (affirming

summary judgment on claims for conspiracy to violate the FWA where the claims had no factual

support).

IV. Plaintiffs Complaint Is Time Barred.

A civil action under the FWA may not be commenced later than two years after the date

upon which the claimant first has a reasonable opportunity to discover the violation. 18 U.S.C.

2520(e). [T]he statute bars a suit if the plaintiff had such notice as would lead a reasonable

person either to sue or to launch an investigation that would likely uncover the requisite facts.

Sparshott v. Feld Entmt, Inc., 311 F.3d 425, 429 (D.C. Cir. 2002). Under section 2520(e), the

cause of action accrues when the claimant has a reasonable opportunity to discover the violation,

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 16 of 21

17

not when she discovers the true identity of the violator or all of the violators. Andes v. Knox,

905 F.2d 188, 189 (8th Cir. 1990); see also Dyniewicz v. United States, 742 F.2d 484, 486 (9th

Cir. 1984) (Discovery of the cause of ones injury, however, does not mean knowing who is

responsible for it.). Like many statutes of limitation, this one does not require the claimant to

have actual knowledge of the violation; it demands only that the claimant have had a reasonable

opportunity to discover it. Davis v. Zirkelbach, 149 F.3d 614, 618 (7th Cir. 1998) (holding that

FWA suit was barred by the statute of limitations where the plaintiff was on inquiry notice that

his rights might have been invaded).

Here, Plaintiffs Complaint is barred by 2520(e) because it was filed on J une 26, 2014,

at least one week, but more likely several weeks, after the statute of limitations had run. In their

Complaint, Plaintiffs allege that [i]n or about mid to late J une 2012, Defendants disseminated

the stolen emails to media outlets and an email from Martinezs email account associated with

the Website Domain was published. Doc. 1 at 10, 40. The email that they are referring to is

an email regarding the PED that went public when Santa Fe New Mexican reporter Steve Terrell

did a piece breaking the story on J une 11, 2012. See United States v. Estrada, No. 1:13-cr-

01877-WJ (Doc. 36-3) (Interview of J ay McCleskey) at 4 (McCleskey advised that the leaked

email was originally reported by the Santa Fe, [sic] New Mexican.)

5

. Mr. Corwin published

that email on his website the next day, J une 12, 2012, with an article detailing how it showed a

violation of the governmental conduct act (using government resources and personnel for private

political purposes). See http://independentsourcepac.com/ped-breaks-nm-law.html. Plaintiffs

5

The Interview of J ay McCleskey is a matter of public record and therefore properly subject to

judicial notice. See, e.g., Pace v. Swerdlow, 519 F.3d 1067, 1072-73 (10th Cir. 2008) (taking

judicial notice of all of the materials in the file from related state court action).

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 17 of 21

18

allege that [t]he release of this email prompted Governor Martinez and her staff to be concerned

that the Website Domain had not in fact simply expired. Doc. 1 at 10, 40. Based on the

objective evidence available in this case, on J une 11 and 12, 2012, Plaintiffs were placed on

inquiry notice that something had gone wrong with Governor Matrinezs @susana2010.com

email account, notice that should have prompted an inquiry into how those emails were

disclosed.

At that point, the statute of limitations began running because Plaintiffs had a reasonable

opportunity to discover any purported violation of the FWA. This conclusion is supported by

Plaintiffs own allegations in the Complaint. They allege that:

After becoming aware that the Website Domain was still active and that emails

intended for recipients at their @susana2010.com email addresses were likely

being diverted to an unknown destination, the original creator of the account,

contacted GoDaddy and informed them that the Website Domain and associated

email addresses had been hijacked. GoDaddy investigated the situation and

determined that someone had indeed fraudulently used his credentials to re-

register the Website Domain. Accordingly, on or about June 19, 2012, GoDaddy

canceled the account associated with the Website Domain and returned it to the

original creator of the account.

Doc. 1 at 10, 41 (emphasis added). Taking these allegations as true, as the Court must, it is

undisputed that Governor Martinez and the holders of the email address @susana2010.com,

including Plaintiffs, knew that the Governors emails had been hijacked before J une 19, 2012

when GoDaddy canceled the account.

That date is confirmed by statements made by the Martinez Administration to the press.

On J une 28, 2012 at 12:05 a.m., the Albuquerque J ournal reported that Scott Darnell, a Governor

Martinez spokesman, had stated that the matter of the allegedly stolen emails was turned over to

the appropriate federal law enforcement authorities last week. See United States v. Estrada, No.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 18 of 21

19

1:13-cr-01877-WJ (Doc. 44-2) at 2 (emphasis added)

6

; see also http://www.abqjournal.com/

115447/news/downs-lawyer-wanted-to-talk-2.html (internet link to article). That means that the

Martinez Administration knew enough to report the issue to law enforcement during the week of

J une 18, 2012, the same week that GoDaddy canceled the email account. Further, the

Albuquerque J ournals J une 28, 2012 article also reported that Martinez last week directed all

state employees under her authority to use their official government accounts when conducting

state business via email. Id. at 3 (emphasis added). The Governors directive was enough to

put Plaintiffs on notice that their @susana2010.com email addresses had been compromised and

should not be used for state government business.

Based on the facts outlined above, the two-year statute of limitations started to run on or

before J une 19, 2012, and most likely on J une 11 or 12, 2014 when the Governor and her staff

first learned that the email address had been compromised. Even using the later of these dates,

the statute of limitations for Plaintiffs FWA claims arising from the allegedly intercepted emails

ran out on J une 19, 2014, a week before Plaintiffs filed their Complaint on J une 26, 2014. As

the statute of limitations had expired, Plaintiffs Complaint must be dismissed as a matter of law

under 18 U.S.C. 2520(e).

CONCLUSION

For these reasons discussed above, Mr. Corwin respectfully requests that the Court

dismiss all of the causes of action alleged against him in the Plaintiffs J une 26, 2014 Complaint,

6

Like the McCleskey Interview, the J une 28, 2012 article is subject to judicial notice as a matter

of public record. See, e.g., Pace, 519 F.3d 1067.

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 19 of 21

20

that the Court enter an order dismissing this action with prejudice as to Mr. Corwin, and for any

other relief that law and justice require.

Respectfully submitted,

ROTHSTEIN, DONATELLI, HUGHES,

DAHLSTROM, SCHOENBURG

& BIENVENU, LLP

Carolyn M. Cammie Nichols

Brendan K. Egan

500 4

th

Street NW, Suite 400

Albuquerque, NM 87102

(505) 243-1443

/s/ Kristina Martinez

Kristina Martinez

1215 Paseo de Peralta

Post Office Box 8180

Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504-8180

(505) 988-8004

Attorneys for Defendant Michael Corwin

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 20 of 21

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that on October 24, 2014, I filed this pleading electronically

through the CM/ECF system, which caused the following counsel to be served by electronic

means, as more fully reflected on the Notice of Electronic Filing:

Angelo J . Artuso angelo.artuso@brytewerks.com

Mark E. Braden MBraden@bakerlaw.com

Gerald G. Dixon jdixon@dsblaw.com

Theodore J . Kobus, III tkobus@bakerlaw.com

Eric A. Packel epackel@bakerlaw.com

Steven S. Scholl sscholl@dsblaw.com

J ames C. Wilkey jwilkey@dsblaw.com

/s/ Kristina Martinez

Kristina Martinez

Case 1:14-cv-00599-MV-SMV Document 17 Filed 10/24/14 Page 21 of 21

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Di MCB DB Pricelist01!07!2018Document1 paginăDi MCB DB Pricelist01!07!2018saurabhjerps231221Încă nu există evaluări

- MTBE - Module - 3Document83 paginiMTBE - Module - 3ABHIJITH V SÎncă nu există evaluări

- BreakwatersDocument15 paginiBreakwatershima sagarÎncă nu există evaluări

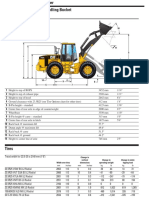

- Cat It62hDocument4 paginiCat It62hMarceloÎncă nu există evaluări

- IMO Publication Catalogue List (June 2022)Document17 paginiIMO Publication Catalogue List (June 2022)Seinn NuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11.traders Virtual Mag OTA July 2011 WebDocument68 pagini11.traders Virtual Mag OTA July 2011 WebAde CollinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beenet Conf ScriptDocument4 paginiBeenet Conf ScriptRavali KambojiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The PILOT: July 2023Document16 paginiThe PILOT: July 2023RSCA Redwood ShoresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mysuru Royal Institute of Technology. Mandya: Question Bank-1Document2 paginiMysuru Royal Institute of Technology. Mandya: Question Bank-1chaitragowda213_4732Încă nu există evaluări

- Metabolic SyndromeDocument4 paginiMetabolic SyndromeNurayunie Abd HalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solved Suppose That The Velocity of Circulation of Money Is VDocument1 paginăSolved Suppose That The Velocity of Circulation of Money Is VM Bilal SaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Bureau of Investigation ManualDocument2 paginiCentral Bureau of Investigation Manualcsudha38% (13)

- Guest AccountingDocument8 paginiGuest Accountingjhen01gongonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance Ratio Analysis Based On Energy Production For Large-Scale Solar PlantDocument22 paginiPerformance Ratio Analysis Based On Energy Production For Large-Scale Solar PlantPrateek MalhotraÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Configure VFD - General - Guides & How-Tos - CoreELEC ForumsDocument13 paginiHow To Configure VFD - General - Guides & How-Tos - CoreELEC ForumsJemerald MagtanongÎncă nu există evaluări

- OL2068LFDocument9 paginiOL2068LFdieselroarmt875bÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9a Grundfos 50Hz Catalogue-1322Document48 pagini9a Grundfos 50Hz Catalogue-1322ZainalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barnett V Chelsea and Kensington Hospital Management CommitteeDocument3 paginiBarnett V Chelsea and Kensington Hospital Management CommitteeArpit Soni0% (1)

- Chapter 3 - A Top-Level View of Computer Function and InterconnectionDocument8 paginiChapter 3 - A Top-Level View of Computer Function and InterconnectionChu Quang HuyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goat Farm ProjectDocument44 paginiGoat Farm ProjectVipin Kushwaha83% (6)

- Functions and Uses of CCTV CameraDocument42 paginiFunctions and Uses of CCTV CameraMojere GuardiarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- COST v. MMWD Complaint 8.20.19Document64 paginiCOST v. MMWD Complaint 8.20.19Will HoustonÎncă nu există evaluări

- HANA Heroes 1 - EWM Lessons Learned (V2)Document40 paginiHANA Heroes 1 - EWM Lessons Learned (V2)Larissa MaiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eletrical InstallationDocument14 paginiEletrical InstallationRenato C. LorillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poverty Eradication Cluster HLPF Position Paper With Case StudiesDocument4 paginiPoverty Eradication Cluster HLPF Position Paper With Case StudiesJohn Paul Demonteverde ElepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tarlac - San Antonio - Business Permit - NewDocument2 paginiTarlac - San Antonio - Business Permit - Newarjhay llave100% (1)

- SecureCore Datasheet V2Document2 paginiSecureCore Datasheet V2chepogaviriaf83Încă nu există evaluări

- Scrum Gantt Chart With BurndownDocument4 paginiScrum Gantt Chart With BurndownAsma Afreen ChowdaryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Splunk Certification: Certification Exam Study GuideDocument18 paginiSplunk Certification: Certification Exam Study GuidesalemselvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20151201-Baltic Sea Regional SecurityDocument38 pagini20151201-Baltic Sea Regional SecurityKebede MichaelÎncă nu există evaluări