Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Effects of Inequity On Human Free-Operant Cooperative Responding A Validation Study

Încărcat de

fatty_mvTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Effects of Inequity On Human Free-Operant Cooperative Responding A Validation Study

Încărcat de

fatty_mvDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 1/13

Title:

Authors:

Source:

Document Type:

Subject Terms:

Abstract:

Full Text Word Count:

ISSN:

Accession Number:

Persistent link to this record

(Permalink):

Cut and Paste:

Database:

The link information below provides a persistent link to the article you've requested.

Persistent link to this record: Following the link below will bring you to the start of the article or citation.

Cut and Paste: To place article links in an external web document, simply copy and paste the HTML

below, starting with "<a href"

To continue, in Internet Explorer, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Be sure to

save as a plain text file (.txt) or a 'Web Page, HTML only' file (.html). In FireFox, select FILE then SAVE

FILE AS from your browser's toolbar above. In Chrome, select right click (with your mouse) on this page

and select SAVE AS

Record: 1

Effects of inequity on human free-operant cooperative responding: A

validation study.

Spiga, Ralph

Cherek, Don R.

Psychological Record. Winter92, Vol. 42 Issue 1, p2917. 11p. 3

Charts, 6 Graphs.

Article

OPERANT behavior

REINFORCEMENT (Psychology)

Examines the effect of disparities in reinforcement frequency on

human free-operant cooperative responding. Role of cooperative

responding to the social interactions which establish and maintain

social groups and institutions; Proportion of cooperative responding;

Cooperative and independent response rates.

4150

0033-2933

9609040822

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=bth&AN=9609040822&site=ehost-live

<A href="http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=bth&AN=9609040822&site=ehost-live">Effects of

inequity on human free-operant cooperative responding: A validation

study.</A>

Business Source Complete

EFFECTS OF INEQUITY ON HUMAN FREE-OPERANT COOPERATIVE

RESPONDING: A VALIDATION STUDY

The effect of disparities in reinforcement frequency on human free-operant cooperative responding was

examined. Points exchangeable for money maintained responding. Two schedule components

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 2/13

alternated during a session. A random interval (Rl) 60-s schedule of point additions was in effect during

the first component and a concurrent R1 60-s R1 60-s schedule was in effect during the second

component. Subjects were instructed that the second component was initiated by another subject and

that they had the option of earning points by working with, or independently of, the other subject.

Independent responses earned points added to a counter marked "YOUR EARNINGS." Cooperative

responses earned points added simultaneously to a counter marked "YOUR EARNINGS" and

"OTHERS EARNINGS." Disparities of reinforcement were produced during the first component by

increasing the frequency of point additions to either the subject's or the fictitious other person's counter.

Disparities benefiting the fictitious other subject reduced cooperative responding, decreased

independent responding, and had no effect on nonsocial responding during the first component.

Disparities benefiting the subject increased cooperative responding in one subject.

Cooperative responding is fundamental to the social interactions which establish and maintain social

groups and institutions (Blau, 1964; Homans, 1961). In studies of cooperative behavior a cooperative

response has been operationally defined as occurring when the responses of two people jointly meet a

performance criterion that produces a reinforcer for both (Deutsch, 1973; Hake & Olvera, 1978; Marwell

& Schmitt, 1975). In the experiment reported in this paper we have operationally defined a "cooperative

response" as one producing reinforcers for the subject and for another ficititous person ostensibly

paired with the subject. The experiment had as its purpose the behavioral validation of an experimental

preparation which could be used to examine drug effects on cooperative behavior in future studies. This

was accomplished by determining whether the behavioral baseline established by this preparation was

sensitive to inequity, a significant social variable (Adams, 1965; Hake & Olvera, 1978; Hake, Vukelich,

& Olvera, 1975; Schmitt & Marwell, 1972).

Until recently the response of a dyed has been the unit of analysis of operant studies of cooperative

behavior (see Hake & Olvera, 1978). Schmitt (1987) examined the rate of an individual's cooperative

and competitive responding when both were concurrently available. Subjects were instructed that

cooperative responses required mutual responding. In this series of experiments subjects were only

able to see a counter indicating the other person's earnings. There was in fact no other subject. Instead

the presence of another subject who mediated cooperative reinforcers was established by instructions.

This modification permits greater experimental control of the rate and reinforcement of cooperative

responses. This is important because response and reinforcement rate have been found to modulate

drug effects (Seiden & Dykstra, 1977; Thompson & Schuster, 1968). Another modification provided a

period during which subjects "worked alone." In future studies this will permit examination of the

specificity of drug effects.

Equity can be operationally defined simply as correspondence in the distribution of reinforcers among

group members (Hake & Olvera, 1978; Hake et al., 1975). Hake et al. (1975) demonstrated that

cooperative responding decreases as a function of increasing inequities in reinforcer magnitude.

Schmitt and Marwell (1972) reported that subjects reduced this disparity by decreasing cooperative

responding or by responding on an alternative which transferred reinforcers (points) from one person to

another when cooperative responding of one individual produced a disparity in reinforcer magnitude

(points added to a counter). In this study equity is defined as correspondence in the number of

reinforcers (earnings) for the subjects and their fictitious counterparts. Inequity is operationally defined

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 3/13

as reinforcer disparity.

In summary the purpose of this study is to determine whether cooperative responding is sensitive to

inequity. Inequity, defined as reinforcer disparity, was produced by manipulating the schedule of point

additions to the fictitious person's or subject's counter.

Method

Subjects

Six healthy, human males between the ages of 18 and 40 were recruited by newspaper advertisements

placed in the part-time employment section. Advertisements did not mention procedural details or

eligibility requirements of the study. Subjects reporting a history or current psychiatric disorder, medical

problem, current use of psychoactive substances including caffeine or nicotine were also excluded from

the study. These precautions were taken because research (e.g., Stitzer, McCaul, Bigelow, &Liebson,

1984) has demonstrated drug effects on human social behavior. Informed consent was obtained

following the instructions.

Apparatus

The subject's response console (HT-603, BRS/LVE, Beltsville, MD) consisted of three buttons, a panel

of three lights and two counters. All experimental events were controlled by an AIM-65 microcomputer

(Dynatem Inc., Irvine, CA). The panel was located in a soundproof, electrically isolated room. Masking

noise was provided by a ventilating fan running continuously during the session.

Instructions

General instructions. Each subject was asked to avoid drinking alcohol during the duration of the study.

They were instructed that expired breath alcohol samples would be obtained before sessions each day

and that the daily sessions would be canceled if the result was positive. Urine samples for drug

screening were collected daily. Positive expired breath alcohol or urine screen produced forfeiture of

bonuses for drug-free attendance. A second positive screen resulted in exclusion.

Preexperimental instructions. Subjects were read the following instructions:

You can earn money by pressing the A button when the A light is on and the B button when the B light

is on. Your B button is effective if and only if the person you are linked with illuminated your B light.

Button A presses earn points without the other person s help. Button B presses earn points for you and

the other person if you and the other person work together. The points you and the other person earn

will be accumulated on the counter marked "Your Earnings" and "Other's Earnings," respectively.

Experimental Contingencies

Two schedule components alternated during a session.

Work alone component. The session began with light A illuminated. While the A light was illuminated,

responses on the A button produced points on the counter marked "YOUR EARNINGS" on a random

interval (Rl) 60-s schedule of reinforcement. Reinforcement was signaled by illumination of a green light

above the counter. The green light was illuminated for 5 s followed by addition of one point. The A light

was off during illumination of the green light and while the point was added to the counter. Responses

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 4/13

were not counted while the green light was illuminated.

During this component, points were also added to the counter marked "OTHER'S EARNINGS"

according to a random time (RT) 60-s schedule of reinforcement. Point additions were signaled by 5-s

illumination of the green light above the counter marked "OTHER'S EARNINGS" followed by addition of

one point. However, responses were effective during this 5-s period.

Choice component. The B light was intermittently illuminated on a RT 120-s schedule. Button A and

Button B responses were reinforced according to concurrent Rl 60-s Rl 60-s schedule of reinforcement

while the A and B lights were illuminated.

Button A (independent) responses produced point additions only to the counter marked "YOUR

EARNINGS." The A and B lights were not illuminated while point additions were being signaled by 5-s

illumination of the green light above the counter.

Button B (cooperative) responses were reinforced by simultaneous point additions to the counter

marked "YOUR EARNINGS" and "OTHER'S EARNINGS." Point additions were signaled by

simultaneous 5-s illumination of the green lights above both of these counters. The A and B lights were

not illuminated during the point addition .

Point additions could not occur for 20 s (change-over-delay, COD, 20 s) following switches from one

option to the other. The duration of the choice component was 2 min.

Daily protocol and session schedule. Subjects arrived at the subject waiting area of the Human

Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory at 0800 hours 5 days a week. A urine sample was obtained and

breath alcohol content (BAC) was measured using Alco Sensor III (Intoximeters, Inc.). Each day

subjects participated in six 30-min sessions. Sessions were conducted at the same times each day and

were separated by 30 min. During the 30-min periods between sessions, subjects were restricted to a

waiting room where they could watch television or read. Lunch was provided each day.

A questionnaire was administered following the sixth session. Subjects were asked (a) to estimate the

number of different individuals with whom they were paired (b) to describe the individual(s) and (c) to

state whether they, or the other person, had earned more points.

Experimental Design

The allocation of points to the subject or the fictitious other person was altered by manipulating the

parameters of the RT (fictitious person's earnings) and Rl (subject's earnings) schedule in effect during

the alone component. Table 1 lists the schedule parameters for responding and for point additions to

the counter marked "Other's Earnings" for each experimental condition.

Experimental conditions were altered when the standard deviation of the proportion of cooperative

responding across five sessions was 10% or less of the mean for those sessions. If responding on an

alternative ceased, the experimental conditions were altered the following session.

Results

Individual rating assessment. All subjects reported that they were paired with at least one person during

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 5/13

the experimental day. Subjects reported being paired with more than one person too infrequently for

statistical analysis. During equity conditions, subjects reported that they earned "about the same" as

their fictitious counterparts.

At the end of the day all subjects reported that the other person earned the most points during

inequitable point distribution. When S-444 and S-452 earned more points than were added to the

counter marked "OTHER'S EARNINGS," they accurately reported that they earned the most points.

Proportion of cooperative responding. The proportion of cooperative responses during the choice

component was calculated by dividing total cooperative responses by the sum of cooperative and

independent responses. As Figure 1 illustrates when the other (fictitious) person ostensibly earned

more points than the subject, the proportion of cooperative responses for S-432 and S-439 decreased.

For S-424 inequity produced greater decreases in cooperative responding during the choice

components following exposure to equitable conditions. Subject S-436 was unaffected by reinforcer

disparities. Figure 2 shows that cooperative responding for S-444 and S-452 decreased during these

same experimental conditions.

Figure 2 shows that, when reinforcer disparities profited the subject rather than the fictitious other

person, the proportion of cooperative responses increased for S-444 from a baseline mean of 0.63 and

0.64, respectively, to 0.78 and 0.83. The proportion of cooperative responses returned to a mean of

0.62 following the last exposure to this inequitable reinforcer distribution. The cooperative responding of

S-452 was unaffected by this disparity.

Cooperative and independent response rates. The subject's rate of responding was calculated by

dividing the number of responses by total time spent in each component. The mean and standard error

of the mean for cooperative and independent responding for each experimental condition is provided in

Table 2. Table 2 illustrates that cooperative and independent response rate for S-424, S-432, and S-

439 was greater than independent response rate during equitable conditions. This relationship was

reversed when the other (fictitious) person ostensibly earned more than the subject. Subject S-424

exhibited a reversal of cooperative and independent response rate only on the second but not the first

exposure to equity conditions.

Table 3 shows that during equitable distribution of reinforcement cooperative response rate exceeded

independent response rate for S-444. Although S-452 exhibited this pattern on first exposure to equity,

no differences between cooperative and independent response rate were observed during subsequent

exposures to the equity condition.

When disparities of reinforcement benefited S-444, cooperative response rate increased and

independent response rate decreased relative to cooperative and independent response rates during

equitable conditions. Following return to equitable conditions cooperative and independent response

rates also returned to baseline values. Subject S-452's independent and cooperative response rate was

unaffected by reinforcer disparities benefiting the subject.

Cooperative response rate decreased and independent response rate increased for S-444 and S-452

when the disparities ostensibly benefited the fictitious subject.

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 6/13

Alone response rate. For all subjects, alone response rate was unaffected by inequity. Mean alone

responding was 255, 300, 112, 255, 198, and 145 responses per minute for S-424, S-432, S-436, S-

439, S-444, and S-452, respectively.

Relative reinforcement frequency. The mean and standard error of the mean score difference for each

subject and experimental condition are provided in Tables 2 and 3. Score differences were calculated

by subtracting the ostensible net earnings of the fictitious other subject from the subject's net earnings.

Positive numbers indicate the subject's score was greater than the other's score. Negative numbers

indicate other's score was greater than the subject's score.

Subjects S-424, S-432, S-436, and S-439 ostensibly earned more points than the fictitious counterpart

during equity. These score differences were as great as score differences during the inequitable point

distribution benefiting the other person. Score differences during inequitable point distribution benefiting

the subject were substantially greater than score differences during equitable conditions.

Discussion

For S-424, S-432, S-439, S-444, and S-452: (1) The proportion of cooperative responses decreased,

(2) the cooperative response rate decreased, and (3) the independent response rate increased when

the fictitious other person earned more points than the subject. As inspection of Tables 2 and 3

demonstrates, these changes minimized accumulated point differences.

Only for S-444 did cooperative responding increase when earnings exceeded the earnings of the

fictitious other. As Table 3 illustrates the number of cooperative, mutual, reinforcers also increased.

However, this increase did not diminish the score difference between the subject and the fictitious

other.

The more general effects of inequities benefiting the other, as compared to the effects of inequities

benefiting the subject, may be explained by the asymmetric contingencies of cooperative and

independent responding during these conditions. When the other fictitious subject earned more than the

subject, responding exclusively on the independent alternative minimized score differences. However,

when the subject earned more than the other fictitious subject, responding exclusively on the

cooperative alternative increased the absolute number of reinforcers for the fictitious other while

maintaining score differences. Thus, in the absence of any effect on score differences cooperative

responding score differences profiting the subject are unlikely to increase. The behavioral effects

observed during inequitable conditions benefiting the fictitious other person are consistent with the

results of other studies demonstrating that disparities of reinforcer magnitude are an aversive stimulus

(Hake & Schmid, 1981; Matthews, 1977; Schmid & Hake, 1983; Schmitt & Marwell, 1972; Weiner,

1977). In this study, as in previous studies, accumulated point differences were minimized by either

decreasing cooperative responding or increasing independent responding, an alternative that reduced

score differences. In studies of cooperative responding and inequity, the cooperative response

produced disparities of reinforcement for paired subjects. Inequity in this study was not produced by the

subject's cooperative response. Nevertheless, cooperative responding decreased and independent

responding increased. This replicates earlier observations and extends previous research by

demonstrating that inequities produced independently of the cooperative relation do affect cooperative

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 7/13

responding.

Following exposure to the inequitable distribution of points cooperative response rate for S-424, S-432,

and S-444 did not return to the levels observed during sessions when points were equitably distributed.

These results and those of Cherek, Spiga, Bennett, and Grabowski (1991), Cherek, Spiga, Steinberg,

and Kelly (1990), and Weiner (1969) demonstrate the influence of behavioral history on human operant

behavior.

Responding during the alone component, alone responding, was unaffected when contingent point

delivery increased or when the subject ostensibly earned less than the other. Our previous analysis

suggests that independent and cooperative response rate was controlled by relative score differences.

Because changes in alone response rate had no effect on these score differences, alone responding

thus did not increase or decrease. Hence, we observed the effect of point disparities on cooperative

and independent responding but not on alone, nonsocial, responding.

Cooperative contingencies are minimally defined when two or more individuals jointly meet a

performance criterion (Hake & Olvera, 1978, Schmitt & Marwell, 1972). The degree of response

interdependence has varied across studies. For example, Schmitt (1987) required subjects to respond

within 0.4 s of the other subject's response. In two-person Prisoner's Dilemma studies of cooperative

responding, subjects have the opportunity to respond without information about the other person's

behavior (Deutsch, 1973; Marwell, Ratcliff, 8 Schmitt, 1969). The procedures of the present study

resemble those of these latter studies. Subjects had no information of the responses of their fictitious

coactors and had only been instructed that they could earn points for themselves and the other person

by "working together." Despite these procedural differences cooperative responding in this study, as in

other studies adopting less stringent definitions of cooperative responding, was affected by point

disparity just as in studies adopting the more stringent criterion of response interdependence. This

suggests to us that cooperative responding generated by these differing preparations form a functional

response class. Procedures used in this study thus can be located on the same dimensions which

characterize prototypical operant studies of cooperative responding (Hake & Olvera, 1978; Hake &

Vukelich, 1972; Schmitt & Marwell, 1972).

The novel experimental procedures used in this study have two advantages recommending their use.

First, is the use of scheduled point additions to a second counter to mimic the presence of a fictitious

other person. Second, because a second person is not required, the study of cooperative, social

responding can be conducted for extended periods. This feature is particularly important in studies of

drug effects, for example, because establishing dose response curves requires maintaining responses

over many sessions.

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate that reinforcer disparity unfavorable to the subject

decreased cooperative and increased independent responding which in turn minimized score

differences. In this study instructions and the availability of a counter marked "OTHER'S EARNINGS"

were used to establish stimuli and responses as social. Under these conditions control by relative score

differences predominated. Although these results were obtained using procedures differing from

prototypical operant studies of cooperative behavior, our results systematically replicate the findings of

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 8/13

these earlier studies (Marwell, Ratcliff, & Schmitt, 1969; Radinsky, 1969; Schmitt & Marwell, 1972).

Table 1

Summary of Reinforcement Contingencies During the

Alone Component by Experimental Condition

Equity Inequity Inequity

Subjects Other Benefits Subject Benefits

Subject Other Subject Other Subject Other

S-424 R160 RT60 R160 RT30 - -

S-432 R160 RT60 R160 RT30 - -

S-436 R160 RT60 R160 RT30 - -

S-439 R160 RT60 R160 RT30 - -

S-444 R160 RT60 R160 RT30 R130 RT60

S-452 R160 RT60 R160 RT30 R130 RT60

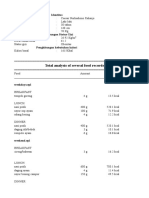

Table 2

Mean and Standard Error of Cooperative and Independent

Response Rate and Score Differences by Experimental Condition

Condition

Inequity Equity Inequity Equity

Subject Other Subject Other Subject

Benefits Benefits Benefits Benefits

Cooperative 384.63 446.60 196.00 272.60

(resp/min) (44.38)(*) (6.84) (43.59) (25.31)

S-424 Independent 66.67 7.00 267.20 70.60

(resp/min) (21.53) (2.02) (34.31) (10.70)

Score Difference 10.33 .81 -2.50 4.36

(1.10) (0.81) (1.10) (0.90)

Cooperative - 207.20 26.33 294.40

(resp/min) (42.21) (15.95) (28.13)

S-432 Independent - 57.60 301.67 125.20

(resp/min) (8.99) (12.51) (19.47)

Score Difference - 5.60 -4.69 6.20

(2.49) (0.66) (1.03)

Cooperative - 188.40 256.00 171.60

(resp/min) (15.25) (17.77) (25.69)

S-436 Independent - 105.60 136.80 155.20

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a% 9/13

(resp/min) (16.26) (11.27) (19.47)

Score Difference - 5.92 -6.60 8.60

(1.00) (0.88) (1.75)

Cooperative - 375.20 72.00 423.00

(resp/min) (27.74) (30.94) (14.10)

S-439 Independent - 77.60 438.33 45.80

(resp/min) (22.62) (44.26) (9.88)

Score Difference - 5.40 -5.25 1.20

(0.93) (1.65) (0.58)

Inequity Equity

Subject Other Subject

Benefits Benefits

Cooperative - -

(resp/min) - -

S-424 Independent - -

(resp/min) - -

Score Difference - -

- -

Cooperative 53.60 -

(resp/min) (16.62)

S-432 Independent 310.60 -

(resp/min) (35.92) -

Score Difference -5.16 -

(1.80)

Cooperative 95.40 -

(resp/min) (20.22)

S-436 Independent 92.80 -

(resp/min) (20.79)

Score Difference -5.40 -

(1.05)

Cooperative 21.30 388.20

(resp/min) (8.99) (21.21)

S-439 Independent 491.67 46.00

(resp/min) (6.44) (13.53)

Score Difference -8.33 2.00

(2.31) (0.84)

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a 10/13

(*) Standard error of the mean is provided except for

conditions with only one session.

Table 3

Mean and Standard Error of Response Rates Number and

Score Differences by Experimental Condition

CONDITION

Equity Inequity Equity

Subject Subject

Benefits

Cooperative 202.20 288.60 233.50

(resp/min) (9.56) (6.11) (9.92)

S-444 Independent 127.17 81.40 131.00

(resp/min) (10.70)(*) (5.08) (16.15)

Score Difference 4.00 22.00 3.50

(0.78) (1.59) (0.87)

Cooperative 124.40 87.40 85.00

(resp/min) (11.57) (10.50) (4.69)

S-452 Independent 61.20 63.00 69.00

(resp/min) (8.99) (4.63) (6.38)

Score Difference 10.80 32.27 10.66

(0.85) (1.53) (0.92)

CONDITION

Inequity Equity Inequity

Subject Subject Other

Benefits Benefits

Cooperative 275.40 223.40 153.96

(resp/min) (18.25) (11.76) (12.18)

S-444 Independent 57.20 135.20 166.80

(resp/min) (15.01) (14.10) (9.67)

Score Difference 23.83 5.60 -9.72

(1.85) (1.29) (0.94)

Cooperative 68.00 74.20 16.00

(resp/min) (8.55) (4.46) (10.10)

S-452 Independent 59.00 53.40 147.00

(resp/min) (0.77) (0.35) (2.50)

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a 11/13

Score Difference 34.10 11.65 -3.50

(1.33) (1.40) (3.48)

Equity Inequity

Subject Other

Benefits

Cooperative 225.60 187.00

(resp/min) (12.14) (11.42)

S-444 Independent 105.80 129.40

(resp/min) (9.39) (7.30)

Score Difference 4.69 -7.00

(0.68) (1.74)

Cooperative 70.40 0.00

(resp/min) (2.97) -

S-452 Independent 62.00 153.00

(resp/min) (0.63) -

Score Difference 10.36 -8.00

(1.57) -

(*) Standard error of the mean is provided except

for conditions with only one session.

Figure 1. Cooperative responses during the choice component

expressed

as the proportion of cooperative and independent responses.

Equitable

and inequitable (other person earns more than subject) conditions

are

indicated by the abbreviation "EQ" and "INEQ/O," respectively.

Figure 2. Cooperative responding during the choice component

expressed as the

proportion of cooperative and independent responses. The

abbreviations "EQ,"

"INEQ/O," and "INEQ/S" indicate equity, inequity benefiting

fictitious other person, and

inequity benefiting subject, respectively.

References

ADAMS, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental

social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267-299). New York: Academic Press.

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a 12/13

BLAU, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

CHEREK, D. R., SPIGA, R., BENNETT, R. H., & GRABOWSKI, J. (1991). Human aggressive and

escape responding: Effects of provocation frequency. The Psychological Record,41,3-17.

CHEREK, D. R., SPIGA, R., STEINBERG, J. L., & KELLY, T. H. (1990). Human aggressive responses

maintained by avoidance or escape from point loss. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior,

53, 293-303.

DEUTSCH, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict New Haven: Yale University Press.

HAKE, D. F., & OLVERA, D. F. (1978). Cooperation, competition and related social phenomena. In A.

C. Catania & T. A. Brigham (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis (pp.208-245). New York:

Irvington.

HAKE, D. F., & SCHMID, T. L. (1981). Acquisition and maintenance of trusting behavior. Journal of the

Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 35,109-124.

HAKE, D. F., & VUKELICH, R. (1972). A classification and review of cooperation procedures. Journal of

the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 18, 333-343.

HAKE, D. F., VUKELICH, R., & OLVERA, D. (1975). The measurement of sharing and cooperation as

equity effects and some relationships between them. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior,

23,63-80.

HOMANS, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt Brace & World.

MATTHEWS, B. (1977). Magnitudes of score differences produced within sessions in a cooperative

exchange procedure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 27, 331 -341.

MARWELL, G., & SCHMITT, D. R. (1975). Cooperation: An experimental analysis. New York:

Academic Press.

MARWELL, G., RATCLIFF, K., & SCHMITT, D. R. (1969). Minimizing differences in a maximizing

difference game. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 12, 158-163.

RADINSKY, T. L. (1969). Equity and inequity as a source of reward and punishment. Psychonomic

Science, 15,293-295.

SCHMID, T. L., & HAKE, D. F. (1983). Fast acquisition of cooperation and trust: A two stage view of

trusting behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 40,179-192.

SCHMITT, D. R. (1987). Interpersonal contingencies: Performance differences and cost effectiveness.

Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 48, 221 234.

SCHMITT, D. R., & MARWELL, G. (1972). Withdrawal and reward reallocation as responses to

inequity. Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, 8, 207-221.

31/8/2014 EBSCOhost

http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=1158cd66-e755-4d57-80a8-2ddeb759f997%40sessionmgr115&vid=4&hid=123&ReturnUrl=http%3a 13/13

SEIDEN, L. S., & DYKSTRA, L. A. (1977). Psychopharmacology: A biochemical and behavioral

approach. New York: Van Nostrand Rheinhold Co.

STITZER, M. L., MCCAUL, M. E., BIGELOW, G. E., & LIEBSON, I. A. (1984). Social stimulus factors in

drug effects in human subjects. In T. Thompson & C. E. Johanson (Eds.), Behavioral pharmacology of

drug dependence. (DHHS Publication No. ADM 81-1137, pp. 30-154). Washington, DC: Government

Printing Office.

THOMPSON, T., & SCHUSTER, C. R. (1968). Behavioralc pharmacology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice

Hall.

WEINER, H. (1969). Conditioning history and the control of human avoidance and escape responding.

Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 12, 1039-1044.

WEINER, H. (1977). An operant analysis of human altruistic responding. Journal of the Experimental

Analysis of Behavior, 27,515-528.

This research was supported by Grants DA03166 (D. R. Cherek, principal investigator) and DA06633

(Ralph Spiga, principal investigator) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Ralph Spiga was also

supported by Post-doctoral Fellowship DA05369 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse during this

period. We thank Lori Zunker for her special assistance and reviewers for their helpful comments.

Reprint requests may be sent to Ralph Spiga, Human Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory, Substance

Abuse Research Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Texas

Health Sciences Center, 1300 Moursund Avenue, Houston, TX 77030.

~~~~~~~~

By RALPH SPIGA, DON R. CHEREK, JOHN GRABOWSKI, and ROBERT H. BENNETT, University of

Texas Health Sciences Center

Copyright of Psychological Record is the property of Springer Science & Business Media B.V. and its

content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright

holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual

use.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Cooperative Problem Solving in RatsDocument8 paginiCooperative Problem Solving in Ratsfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rise of Dispersed Ownership The Roles of Law and The State in The Separation ofDocument83 paginiThe Rise of Dispersed Ownership The Roles of Law and The State in The Separation offatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blass. Understanding Bchavior in The Milgram Obedience ExperimentDocument16 paginiBlass. Understanding Bchavior in The Milgram Obedience Experimentfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stagesofsocial Development: B. R. MannDocument2 paginiStagesofsocial Development: B. R. Mannfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins of Altruism in Offspring Care: Stephanie D. PrestonDocument37 paginiThe Origins of Altruism in Offspring Care: Stephanie D. Prestonfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1960 Mower LearningtheoryDocument585 pagini1960 Mower Learningtheoryfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Law and PhilosophyDocument14 paginiSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Law and Philosophyfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Economic AssociationDocument130 paginiAmerican Economic Associationfatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Economic Psychology: Erte Xiao, Cristina BicchieriDocument15 paginiJournal of Economic Psychology: Erte Xiao, Cristina Bicchierifatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Katz, Bodily y Wright (2008)Document12 paginiKatz, Bodily y Wright (2008)fatty_mvÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Modern Theory of Biological Evolution - An Expanded Synthesis (2004!03!17)Document22 paginiThe Modern Theory of Biological Evolution - An Expanded Synthesis (2004!03!17)Marlon Dag100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Tugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RDocument2 paginiTugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RCaesar 'nche' NurhadionoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Campus DrinkingDocument2 paginiCampus DrinkingLiHertzi DesignÎncă nu există evaluări

- EV-H-A1R 54C - M - EN - 2014 - D - Heat Detector SalwicoDocument2 paginiEV-H-A1R 54C - M - EN - 2014 - D - Heat Detector SalwicoCarolinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diablo LED Wall LightDocument2 paginiDiablo LED Wall LightSohit SachdevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Air Conditioning Is Inoperative, Fault Code 91eb11 or 91eb15 Is StoredDocument5 paginiAir Conditioning Is Inoperative, Fault Code 91eb11 or 91eb15 Is Storedwasim AiniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ProjectxDocument8 paginiProjectxAvinash KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- PROJECT PROPOSAL AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT TOOLS GROUPWORK (Situation No. 3 - BSSW 3A)Document21 paginiPROJECT PROPOSAL AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT TOOLS GROUPWORK (Situation No. 3 - BSSW 3A)Hermida Julia AlexandreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Declaration Page Sample Homeowners 12Document1 paginăDeclaration Page Sample Homeowners 12Keller Brown JnrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radiador y Sus Partes, Motor Diesel 504BDTDocument3 paginiRadiador y Sus Partes, Motor Diesel 504BDTRamón ManglesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retropharyngeal Abscess (RPA)Document15 paginiRetropharyngeal Abscess (RPA)Amri AshshiddieqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selectivities in Ionic Reductions of Alcohols and Ketones With Triethyisilane - Trifluoroacetic AcidDocument4 paginiSelectivities in Ionic Reductions of Alcohols and Ketones With Triethyisilane - Trifluoroacetic AcidJan Andre EriksenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Textile Reinforced - Cold Splice - Final 14 MRCH 2018Document25 paginiTextile Reinforced - Cold Splice - Final 14 MRCH 2018Shariq KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamental Unit of Life 1-25Document25 paginiFundamental Unit of Life 1-25Anisha PanditÎncă nu există evaluări

- TG Chap. 10Document7 paginiTG Chap. 10Gissele AbolucionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ens TecDocument28 paginiEns TecBorja CanalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1 Animal CareDocument8 paginiLesson 1 Animal CareLexi PetersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reuse DNA Spin ColumnDocument6 paginiReuse DNA Spin ColumnashueinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise 6Document2 paginiExercise 6Satyajeet PawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guia Laboratorio Refrigeración-2020Document84 paginiGuia Laboratorio Refrigeración-2020soniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ulangan Tengah Semester: Mata Pelajaran Kelas: Bahasa Inggris: X Ak 1 / X Ak 2 Hari/ Tanggal: Waktu: 50 MenitDocument4 paginiUlangan Tengah Semester: Mata Pelajaran Kelas: Bahasa Inggris: X Ak 1 / X Ak 2 Hari/ Tanggal: Waktu: 50 Menitmirah yuliarsianitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- VSR 411 QB AnaesthesiaDocument7 paginiVSR 411 QB Anaesthesiavishnu dathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic: Going To and Coming From Place of WorkDocument2 paginiTopic: Going To and Coming From Place of WorkSherry Jane GaspayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peseshet - The First Female Physician - (International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 32, Issue 3) (1990)Document1 paginăPeseshet - The First Female Physician - (International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 32, Issue 3) (1990)Kelly DIOGOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oseco Elfab BioPharmaceuticalDocument3 paginiOseco Elfab BioPharmaceuticalAdverÎncă nu există evaluări

- School: Sta. Maria Integrated School Group No. Names: Energy Forms & Changes Virtual LabDocument3 paginiSchool: Sta. Maria Integrated School Group No. Names: Energy Forms & Changes Virtual LabNanette Morado0% (1)

- Resume Rough DraftDocument1 paginăResume Rough Draftapi-392972673Încă nu există evaluări

- EdExcel A Level Chemistry Unit 4 Mark Scheme Results Paper 1 Jun 2005Document10 paginiEdExcel A Level Chemistry Unit 4 Mark Scheme Results Paper 1 Jun 2005MashiatUddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insurance CodeDocument18 paginiInsurance CodeKenneth Holasca100% (1)

- Molecular MechanicsDocument26 paginiMolecular MechanicsKarthi ShanmugamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dryden, 1994Document17 paginiDryden, 1994Merve KurunÎncă nu există evaluări