Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

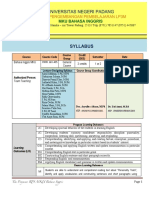

Language User Groups and Language Teaching

Încărcat de

Yeasy AgustinaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Language User Groups and Language Teaching

Încărcat de

Yeasy AgustinaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Language User Groups and Language Teaching

(Vivian Cook)

Multi-competence Background

Multi-competence was originally defined as the compound state of a mind with two

grammars (Cook, 1991) !his was reworded as the knowledge of two languages in one

mind (Cook, "##$), %ecause some people took the term grammar in the narrow meaning of

synta& rather than in the %road meaning of linguistic competence intended Multi-

competence emphasi'ed the relationships of the languages in the same person mind rather

than the separate e&istance of a first language and a interlanguage

(s multi-competence came out of a Chomskyan tradition, it started with the

indi)iduals knowledge of language Cook ("##$) distinguished fi)e meanings of language *

1 ( representation system known %y human %eings + human language

" (n a%stract entity + the ,nglish language

- ( set of sentences + e)erything that has or could %e said + the language of the .i%le

/ !he possession of a community + the language of 0rench people

1 !he knowledge in the mind of an indi)idual + 2 ha)e learnt 0rench as a foreign

language for 3 years

Communities and Language User Groups

!he core )alue of a community is, howe)er, almost in)aria%ly taken to %e a single

language4 a minority ethnic community is seen as identifying itself with its own language,

protecting it and maintaining it as a heritage (n indi)iduals use of two languages supposes

the e&istence of two different language communities4 it does not suppose the e&istence of a

%ilingual community (Mackey, 19$") !his denies the reality of the multilingual communities

in the world with more than one language at their core

5a)ing two languages may %ring people into a different multilingual community (t

one le)el people may %elong to nati)e speaker communities who talk to fellow-mem%ers

6ust as the concept of indi)idual multi-competence stressed the 7" user in their right, so the

multi-competence of the community stresses the multilingual community in its own right, not

as a collection of people with different 71s %ut as a community with an integral use of two or

more languages (ccording to Canagara8ah ("##$), 7inguistic di)erdity is at the heart of

multilingual communities !here is constant interaction %etween language groups, and they

o)erlap, interpenetrate, and mesh in fascinating ways

The De Swaan Hierarchy

9iegel ("##:) used sociolinguistic settings, %ased on the idea of dominant language,

to show how the language user groups %e categori'ed (n alternati)e is the hierarchy

proposed %y ;e 9waan ("##1) *

2n the scheme, languages differ in terms of geographical and function areas + where

they are used and why (t the %ottom come languages that are peripheral4 they are used

within a circumscri%ed territory for the purposes of a local community (s the term

peripheral seems to con)ey some e)aluation, the term local is more neutral <e&t up the

hierarchy come central languages users within a geographical area for communication

%etween different groups for education and go)ernment (%o)e this come supercentral

languages that ha)e a wider geographical spread and are used for cross-national

communication for a limited range of functions 0inally at the top come hypercentral

languages used chiefly %y non-nati)e speakers across the glo%e for a large range of

purposes

Groups o Language Users

7anguage users can %e di)ided into groups according to the four ;e 9waan le)el

!he first group is people using their first language with each other in the local language

geographical territory !his is the sole group to contain only monolingual nati)e speakers of

the language !he second group consists of permanent residents using a central second

language to communicate with the wider community outside their local language group

!he third group consists of people using a supercentral language across national or

linguistic %orders for a specific range of functions of language rather than for all functions

9upercentral languages can %e used for wider pu%lic or pri)ate functions across different

countries !he fourth group consists of people using a hypercentral second language,

perforce language, glo%ally across all countries and used for all possi%le second language

functions

!he ;e 9waan analysis treats language users in terms of wider group mem%ership

and of language function ;e 9waan ("##1) sees the ac=uisition of second languages as

typically going up the hierarchy 9peakers of a local language ha)e to learn a central

language to function in their own society 9peakers of a central language need to learn a

supercentral language to function within their region 9peakers of a supercentral language

need the hypercentral language to function glo%ally, true of any%ody %ut a nati)e speaker of

,nglish

Language Groups and SL! "esearch

9ome 97( research has looked at this type of ac=uisition from ;ulay and .urt (19$-)

studying grammatical morphemes ac=uisition among 9panish-speaking children in California

to 5annan ("##/) doing the same with ,ast ,nd .engalis Central language ac=uisition %y

local groups has not howe)er usually %een distinguished from other types of ac=uisition,

e&cept through the second>foreign language distinction

!he important point in 97( research here is that we need to %e e=ually careful in

specifying the language groups the learners %elong to and want to %elong to, rather than

treating 97( research as a unified whole ?enerali'ing from the taught C7 group is

particularly difficult as we cannot isolate the effects of teaching 2nterestingly for many of the

other groups teaching is not a ma8or concern4 it is simply taken for granted that you ha)e to

%e multilingual in Central (frica or 2ndia

Language Groups and Language Teaching

Group B Learning and Teaching of Central Languages

5istorically the teaching of central languages has concerned ethnic minority children

and immigrants %y ha)ing a local language at home and may %e directly taught the language

at school or mainstreamed into ordinary classes 2t needs to take account of the e&tent to

which the o)erall community is multi-competent or monolingual

!he (dult ,9@7 Core Curriculum for ,ngland (;f,9, "##1) pro)ides an e&le of

educational thinking on this topic !he target is four types of learners* settled communities

such as 5ong Aong, refugees, migrant workers and partners and spouses of learners + all

essentially prospecti)e ?roup . mem%ers 2t aims at defi ning in detail the skills, knowledge

and understanding that non-nati)e ,nglish speakers need in order to demonstrate

achie)ement of the national standards (;f,9, "##1* $) 2n other words, the only goal of

,9@7 learners is to %ecome part of the ?roup ( rather than part of a ?roup .

Group C Teaching of Supercentral Languages

@ne characteristic of supercentral languages is their limited use across %orders for a

small range of functions 9ince the 19:#s this speciali'ed functionality has %een the concern

of many an ,9B course, ranging from courses for oilrig-workers to courses for general

practitioners4 to the consternation of one of my e&-students, her first teaching 8o% was

,nglish to a 6apanese se&-shop manager (part from ,nglish, the hypercentral language, all

of these are supercentral languages with a sphere of influence e&tending outside their own

countries and sometimes outside ,urope, say with 0rench and 9panish 7anguage learning

in schools in ,urope is o)erwhelmingly upward in the ;e 9waan hierarchy towards

supercentral languages and the hypercentral language

Group D Teaching the Hypercentral Language

!he hypercentral language ,nglish is the one that is all things to all people, not

confined to a particular territory or a particular function 2ts users do not ha)e to take part in a

particular society, unlike ?roup ., or utili'e more specifi c functions in a wider territory, unlike

?roup C4 potentially they use ,nglish with anyone anywhere for almost any reason ?roup (

nati)e speakers of ,nglish ha)e no special status, indeed may struggle with some aspects of

hypercentral ,nglish more than their non-nati)e fellows ?roup ; speakers retain their own

71 identities while at the same time using an 7" to deal with each other + language for

communication

Biligual and Multiligual #ducation

(Cristopher J. Hall)

Deinition and $urposes

!he criterion for what makes a prohramme %ilingual or multilingual in a particular

conte&t can %e the language %ackgrounds of the learners and>or the language(s) they are

taught in !he purposes of %ilingual and multilingual education programmes are similarly

di)erse, rangung from de)elopment of ad)anced le)els of proficiency and academic

achie)emet in %oth target languages to the promotion of academic skills in a dominat

language %ut not in the pupils home language

Ce present here a three-part framework for understanding how education in multiple

lamguage is commonly organi'ed Ce %egin %y distinguishing %etween frames that are

(1)language-%ased, (") content-%ased and (-) conte&t-%ased

Language-%ased &rames

!he strong-weak dichotomy in %ilingual education refers to the %alance in classroom

usage %etween the two languages in)ol)ed

2n %ilingual a minority language is distinguished from a dominant language according

to what its used (its conte&t)

( heritage language is the language of a minority community )iewed as a property of

the groups cultural history, and is often in danger loss as third generations grow up

%eing un-preundere&posed to the language

.illiteracy is literacy in two (or more) languages

Content-%ased &rames

Children engage in de-facto %ilingual education when they and their teachers

implicity draw on su%8ect knowledge ac=uired pre)iously in a language which is

diffent from the language of instrictruction

( sheltered ,nglish programme is one in which school pupils with limited proficiency

in the target language get instruction in ,nglish as an additional language along with

other su%8ect taught in ,nglish , until they can 8oin students who ha)e the proficiency

re=uired to engage in mainstream classrooms

Su%mersion education

Bupils are placed in classes with students who are nati)e>proficient speakers of the

dominant language, and their academi progress is e)aluated using measures

designed to assess the performance of nati)e speakers and for comparison with the

norms esta%lished for them 9u%mersion education remains the most common form

of schooling for language minority students (?arcia, "##9)

Transitional %ilingual education

!ransitional %ilingual education is su%stracti)e using the first language as a

temporary medium for gaining proficiency in the (dominant) second language an

important factor in the organi'ation of !., programmes is the length of time that

students are permitted to study in their 71 %efore %eing mo)ed into classes designed

for nati)e speakers of the dominant language

Maintenance %ilingual education

Maintenance %ilingual education is addicti)e, aiming to complement and strengthen,

rather than replace, the ( minority ) first language the maintenance %ilingual

education model is intended for immigrant pupils thought likely to return to their home

countries and whose successful return woud ideally included %eing a%le to participate

in schools there

'mmersion

!he term immersion refers to programms designed to teach content in the target

language, %ut in a way that does not (intentionally) harm the learners 71 Aey

)aria%les in immersion programmes include the language(s) of instruction and the

home language(s) of the students, with one way and two-way immersion

Community language teaching

Community language teaching is an approach to heritage langauge education

adopted in the DA, (ustralia, the <etherlands, and other countries in which the home

languages of ethnic minorities are taught and used as languages of instruction in

schools and community centres

Heritage language programmes

5eritage language programmes share the assumption that there is educational )alue

in teaching students in and a%out the historic language(s) of their community !he

specific purposes are )ary, from promoting oral fluency to foster intergenerational

communication, to de)eloping academic literacies as a motor for d)anced %iliteracy

and uni)ersity study 9trong e&les of heritage language programmes ha)e

en)ol)ed in many places, although they are not always known locally %y this name

Conte(t-%ased &rames

!his frame can %e further di)ided into macro-and micro-le)el conte&t)

Macro-le*el conte(ts

Consider the following statement %y (rgentine-D9 scholar Maria .risk, comparing

perceptionsof %ilingual education in the D9 and other nations*

Much of the de%ate on %ilingual education (in the D9) is wasteful, ironic, hypocritical

and regressi)e 2t is wastefuk %ecause instead of directing attention directly to sound

educational practices, it has led to ad)ocating specific model %ased solely on what

language should %e used for what purpose 2t is ironic %ecause most attacks on

%ilingual education arise from an unfounded fear that ,nglish will %e neglected in the

Dnited 9tates, whereas, in fact, the rest of the world fears the opposite4 the attraction

of ,nglish and interest in (merican culture are seen %y non-,nglish speaking nations

as a threat to their own languages and cultures 2t is hypocritical %ecause most

opponents of using languages other than ,nglish for instruction also want to promote

foreign language re=uirements for high school graduation 0inally, it is regressi)e and

&enopho%ic %ecause the rest of the world considers a%ility in at least two languages

to %e the mark of a good education (.risk, 1993, p1:#)

Micro-le*el conte(ts

,lite and folk %ilingualism are terms used %y 9u'anne Eomaine to la%el the

difference in socioeconomic circumtances and moti)ations %etween thise who seek

to %ecome %ilingual out of choice, often for increased prestige and those who seek to

%ecome %ilingual out of necessity, often of sur)i)al

'ntegrating the &rameworks

!he wide range of practices reflect the fact that %ilingual and multilingual

programmes are not only linguistic and learning endea)ours, %ut also political and economic

arrangements 2n response to this comple&ity, applied linguists need to %e a%le to

understand programmes of %ilingual and multilingual education from the multiple and

o)erlapping persoecti)es of language, content and conte&t, with special attention to glo%al

and local situations

,ssentially , we can think of %ilingual and multilingual programmes as %eing

organi'ed along one or more of three primary orientations*

7anguage as pro%lem

7anguage as right

7anguage as resources

Characteristics o #ecti*e $rogrammes

@ur reading of the research on %ilingual and multilingual education suggests that the

most effecti)e programmes are those that ha)e the support and in)ol)ement of students,

families and teachers, and in these e&ceptional cases indi)idual programmes de)elop and

adopt practices that %est fit their needs

9ome key features of successful programmes can %e offered here*

(ll pupils learn %est in a language they understand

!eacher preparation

9chool autonomy is a condition for success

Barents and other care-gi)ers, teachers, administrators and school staff should %e in

agreement a%out pri)iding support for ad)anced %ilingualism and specially, should

ha)e respect for the minority language

Brogram should challenge students to work at high academic le)els, %ecause low

e&pectations dont foster academic success in any language

"oles or !pplied Linguists

'n Schools

(round the world, finding suffcicient num%ers of linguistically proficient and well-

trained language professionals poses a critical challenge to the success of %ilingual

and multilingual schooling !he o%)ious need for classroom teachers programmes

may re=uire*

.ilingual assistants for monolingual teachers

Criters and designers a%le to produce curriculum, forms of assesment and print and

digital materials in non-dominant language

9chool administrators a%le to communicate the special need of %ilingual learners to

those education and pu%lic authorities which regard monolingualism and monolingual

schooling as normal and %ilingual or multilingual learners as something of a mystery

or nuisance

+utside schools

<ot all applied linguists are classroom teachers or work in school, of course %ut there

are also )alua%le contri%utions that they can make with the remit of informing the

education profession and the general pu%lic Conducting and reporting research on

%ilingualism in non-scholarly forums is particularly important, %ecause the results of

research on %ilingualism and learning in actual programmes too rarely find their way

into pu%lic discourse on, or policy a%out, %ilingual and multilingual education

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Development of Speech ProductionDocument24 paginiThe Development of Speech ProductionNadia TurRahmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communicative Syllabus Design: Patricia A. PorterDocument22 paginiCommunicative Syllabus Design: Patricia A. Porterزيدون صالحÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contoh Proposal VocabularyDocument13 paginiContoh Proposal VocabularyfarahdilafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formal vs informal language learning environmentsDocument7 paginiFormal vs informal language learning environmentsEmmanuella MonicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Need Analysis For WaiterDocument2 paginiNeed Analysis For WaiterJonathan AlexanderÎncă nu există evaluări

- How ELT Materials Can Facilitate Language AcquisitionDocument2 paginiHow ELT Materials Can Facilitate Language AcquisitionCindy LleraÎncă nu există evaluări

- We Do Need MethodDocument5 paginiWe Do Need MethodVeronica VeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- FINAL REVISI-RPS MKU Bahasa Inggris 2019 (English) PDFDocument13 paginiFINAL REVISI-RPS MKU Bahasa Inggris 2019 (English) PDFzulfa fajryani0% (1)

- Teaching Media for Young LearnersDocument18 paginiTeaching Media for Young LearnersbibitpurnamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Silabus ESPDocument5 paginiSilabus ESPujuimutÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modul Translation 1Document16 paginiModul Translation 1alfianÎncă nu există evaluări

- PhDL 505 Approaches in Language Curriculum Design Goals Content SequencingDocument6 paginiPhDL 505 Approaches in Language Curriculum Design Goals Content SequencingFe CanoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rencana Pembelajaran Semester (RPS) : Mata Kuliah: English Morphology Kode: MKK31 Dosen Pengampu: Adip Arifin, M.PDDocument18 paginiRencana Pembelajaran Semester (RPS) : Mata Kuliah: English Morphology Kode: MKK31 Dosen Pengampu: Adip Arifin, M.PDIndra PutraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Material Cross Cultural UnderstandingDocument31 pagini1 Material Cross Cultural UnderstandingcyevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessing Speaking BrownDocument3 paginiAssessing Speaking BrownApriliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Makalah Sociolinguistic DIALECTS and VARIETIESDocument8 paginiMakalah Sociolinguistic DIALECTS and VARIETIESellysanmayÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7.83201429 - An Analysis of Linguistic Competence in Writing TextsDocument15 pagini7.83201429 - An Analysis of Linguistic Competence in Writing TextsUcing Garong Hideung100% (1)

- Goals, Outcomes and CompetenciesDocument11 paginiGoals, Outcomes and CompetenciesRabiatul syahnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contoh Desain Pembelajaran Bahasa InggrisDocument6 paginiContoh Desain Pembelajaran Bahasa Inggrisfifah12Încă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Mata Kuliah ESPDocument12 paginiTugas Mata Kuliah ESPSuryaa Ningsihh100% (1)

- Chapter 1Document30 paginiChapter 1Mark Anthony B. AquinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher-Student Communication Patterns AnalyzedDocument7 paginiTeacher-Student Communication Patterns AnalyzedAlexandra RenteaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Influence of English Song and Joox Application Toward Students' Pronunciation at The Eighth Grade of SMPN 6 Kota SerangDocument217 paginiThe Influence of English Song and Joox Application Toward Students' Pronunciation at The Eighth Grade of SMPN 6 Kota Serangrini dwi septiyaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition of WritingDocument8 paginiDefinition of WritingANGELY ADRIANA CHACON BLANCOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal UTS ESP 2020Document2 paginiSoal UTS ESP 2020Pou PouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas FixDocument2 paginiTugas Fixdita juliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Makalah Pidgin and CreolesDocument10 paginiMakalah Pidgin and Creolesalyssa ayuningtyas100% (1)

- RPP (Praktik Mengajar I) ListeningDocument5 paginiRPP (Praktik Mengajar I) ListeningAhmad yaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating Four Language SkillDocument10 paginiIntegrating Four Language SkillSalwa ZhafirahbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pengertian InvitationDocument7 paginiPengertian InvitationIlya Afiyanti100% (1)

- Material Design ESPDocument1 paginăMaterial Design ESPMaham ArshadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Materials Seminar On ELTDocument23 paginiCourse Materials Seminar On ELTKhusnul Khotimah0% (1)

- Acquiring Knowledge For L2 UseDocument15 paginiAcquiring Knowledge For L2 UselauratomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acquiring communicative competence through writingDocument27 paginiAcquiring communicative competence through writingzahraa67% (3)

- "Textbook Analysis by Jeremy Harmer": Textbook Analysis Lecturer: Mohammad Fikri NK, M.PDDocument14 pagini"Textbook Analysis by Jeremy Harmer": Textbook Analysis Lecturer: Mohammad Fikri NK, M.PDFebriyani WulandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessing ReadingDocument5 paginiAssessing ReadingFloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skripsi The Influence of Multimedia Facilities Toward Stucents' Listening SkillsDocument61 paginiSkripsi The Influence of Multimedia Facilities Toward Stucents' Listening SkillsRamdanul Barkah100% (2)

- Course Planning & Syllabus Design DimensionsDocument44 paginiCourse Planning & Syllabus Design DimensionsMifta hatur rizkyÎncă nu există evaluări

- English For Specific Purposes MakalahDocument8 paginiEnglish For Specific Purposes Makalah20ratna50% (4)

- Proposal ELT ResearchDocument16 paginiProposal ELT ResearchRiska Alfin Pramita100% (5)

- LAtihan Edit Background AcakDocument4 paginiLAtihan Edit Background AcakTiara VinniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contrastive and Error AnalysisDocument22 paginiContrastive and Error AnalysisAan SafwandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning Goals and Learning OutcomesDocument72 paginiPlanning Goals and Learning OutcomesDedi Kurnia100% (2)

- The Use of Smartphone On English Learning Quality of The First Grade Student at SMP Negeri 3 BanawaDocument12 paginiThe Use of Smartphone On English Learning Quality of The First Grade Student at SMP Negeri 3 BanawaLidya AfistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2739 Chapter 3 Exercises and Answer Key.Document3 pagini2739 Chapter 3 Exercises and Answer Key.luihwangÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Study Resource Was: e Se Pi Ɪ Ɛ ꞮDocument5 paginiThis Study Resource Was: e Se Pi Ɪ Ɛ ꞮYolanda FelleciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discourse Analysis MakalahDocument7 paginiDiscourse Analysis Makalahamhar-edsa-39280% (1)

- Research Method in ELTDocument2 paginiResearch Method in ELTMukhamadrandijuniartaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handout Indonesian English Translation PDFDocument36 paginiHandout Indonesian English Translation PDFLinda AsmaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mona Baker - Equivelance Theory by Assma MuradDocument12 paginiMona Baker - Equivelance Theory by Assma MuradA.h.MuradÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regional and Social VariationDocument4 paginiRegional and Social Variationdyo100% (2)

- Silabus Bahasa Inggris Kelas XiiDocument8 paginiSilabus Bahasa Inggris Kelas Xiipo_er75% (4)

- Buku Ajar Vocabulary II Lengkap PDFDocument48 paginiBuku Ajar Vocabulary II Lengkap PDFOfo FrenzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deixis: in SemanticsDocument24 paginiDeixis: in SemanticswidyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Descriptive Text PDFDocument4 paginiDescriptive Text PDFNandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Makalah English Teaching MethodDocument47 paginiMakalah English Teaching MethodliskhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elt Trends 2 in Asia PDFDocument5 paginiElt Trends 2 in Asia PDFmarindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition of TranslationDocument2 paginiDefinition of TranslationAlexis Martinez Constantino100% (1)

- Assessing ListeningDocument6 paginiAssessing ListeninglistasinagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociolinguistics Notes Monolingualism Multilingualism Legon 2015 ClassDocument23 paginiSociolinguistics Notes Monolingualism Multilingualism Legon 2015 ClassHassan AbdallaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Help at Hand - Ideas For The Developing TeacherDocument38 paginiHelp at Hand - Ideas For The Developing TeacherLuka RisticÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of Collocation in English Language Teaching (Copy Cite)Document6 paginiThe Importance of Collocation in English Language Teaching (Copy Cite)Nguyễn Kim KhánhÎncă nu există evaluări

- HrhhreDocument3 paginiHrhhreImran KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nef Elem Progresstest 1-4 B PDFDocument4 paginiNef Elem Progresstest 1-4 B PDFPeter Torok KovacsÎncă nu există evaluări

- CI422 Final ProjectDocument14 paginiCI422 Final ProjectKatie KalnitzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential English For Foreign Students. Book 3Document317 paginiEssential English For Foreign Students. Book 3ktr96% (25)

- A Discourse Grammar of The Greek New TestamentDocument86 paginiA Discourse Grammar of The Greek New TestamentSidney WebbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liceul Teoretic ,,George Calinescu’’ Constanta New Zealand CultureDocument7 paginiLiceul Teoretic ,,George Calinescu’’ Constanta New Zealand CultureElena StoicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Budd Chants 01Document134 paginiBudd Chants 01meytraeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stenst ADocument16 paginiStenst ANorman Argie NofiantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Year 4Document4 paginiLesson Plan Year 4Hfs MkhtrÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 2019-20-21Document15 paginiEnglish 2019-20-21kv117Încă nu există evaluări

- Eg National Standards of EFLDocument40 paginiEg National Standards of EFLAhmed Gad Zayed AbdelaalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ujian Akhir SemesterDocument8 paginiUjian Akhir Semesteralfi khoirulÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Dictionary of Japanese Particles - Sue A KawDocument364 paginiA Dictionary of Japanese Particles - Sue A KawOlga Feniuk100% (3)

- Teaching World Englishes - Group4 - AnaDocument26 paginiTeaching World Englishes - Group4 - AnaAntje Mariantje100% (1)

- Grammar Reinforcement ExercisesDocument7 paginiGrammar Reinforcement ExercisesYan GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtual School Offers Flexible Language Lessons AnytimeDocument13 paginiVirtual School Offers Flexible Language Lessons AnytimeWerner DeJuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammar: Common Challenges For Spanish-Speaking Learners of EnglishDocument5 paginiGrammar: Common Challenges For Spanish-Speaking Learners of EnglishJesús Belda NetoÎncă nu există evaluări

- It's Been Said Before - A Guide To The Use and Abuse of ClichesDocument249 paginiIt's Been Said Before - A Guide To The Use and Abuse of ClichesJohn AbeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monograph Rocha&GarciaDocument61 paginiMonograph Rocha&GarciaKevin Reyes PauthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eng8 - Q1 - Mod3 - Listening Comprehension - Version3 PDFDocument37 paginiEng8 - Q1 - Mod3 - Listening Comprehension - Version3 PDFMarcy Megumi Sombilon83% (12)

- A Syntactic Analysis of The English Discourse Marker Only and Its Vietnamese Translational EquivalentsDocument11 paginiA Syntactic Analysis of The English Discourse Marker Only and Its Vietnamese Translational EquivalentsThư Nguyễn AnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Region IX Eden LandDocument8 paginiRegion IX Eden LandMely DelacruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Actividad de Ingels 1Document4 paginiActividad de Ingels 1Leydy Maryuri Diossa ReyÎncă nu există evaluări

- FCE - Exam: B2 First For SchoolsDocument26 paginiFCE - Exam: B2 First For SchoolsNele Loubele PrivateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listening StrategiesDocument18 paginiListening StrategiesGalillea LalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Writing Exam - English VDocument8 paginiFinal Writing Exam - English VYEINER DAVID PAJARO OTEROÎncă nu există evaluări

- Similarities and Differences of Varieties of EnglishDocument28 paginiSimilarities and Differences of Varieties of EnglishGat TorenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Ab EnglishDocument2 paginiWhy Ab EnglishJennette BelliotÎncă nu există evaluări