Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Case 1 Toyota

Încărcat de

pheeyonaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Case 1 Toyota

Încărcat de

pheeyonaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

1

Toyota Motor Companys Recall Debacle: Did Toyota Take a Wrong Turn?

Case study by Andrea Markowitz

It was a public relations disaster of unimagined proportions for the automotive manufacturing industry

icon. On September 29, 2009, Toyota Motor Company (TMC) announced that it would recall 3.8 million

vehicles in the United States, due to unintended acceleration. By May of 2011, the recall surged to

approximately 14 million vehicles.

A media outcry began after an accelerator pedal caught in the floor mat and caused the deaths of a

California highway patrol officer and three family members in August of 2009. Toyotas president of

three months, Akio Toyoda, responded to the tragedy by offering a public apology. Both Toyota and the

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) investigated what may have caused the

unintended acceleration, and both concluded that a faulty design allowed accelerator pedals to become

caught in the floor mat and to stick in the accelerating position. (Toyota also noted, however, that nearly

all of the crashes that occurred while the driver was trying to brake resulted from the driver mistakenly

pressing the accelerator instead of the brake.) U.S. Government regulators fined Toyota nearly $50

million for taking too long to initiate recalls.

On May 23, 2011, a seven-member North American Quality Advisory Panel (NAQAP), created in 2010 by

Toyota and headed by former United States Secretary of Transportation Rodney E. Slater, released a

report that said Toyota had been slow to discover the floor mat and accelerator pedal issues because the

company ignored customer and government regulator complaints about sudden acceleration. It also said

Toyota had failed to apply its Toyota Way manufacturing process principles, which, in part, direct

employees to detect and respond to problems quickly, and to encourage timely and effective

communications between employees, management and executives.

The Toyota Way, 2001

In 2001, Toyota executives created corporate principles to encourage the continuous improvement of

processes and people through training, teamwork, and management/employee relations, which they

dubbed the Toyota Way. On December 21 of that year, a Toyota press release announced that in

January, 2002, the company would establish the Toyota Institute, an internal organization for training

Toyota Way principles to executives and middle management in Japans TMC and its overseas affiliates.

The press release stated that these principles considered the effects of globalization and diversity

(people with diverse perceptions) on human resources and the global Toyota team, and that Toyota

conducted a review of its human-resource training structures to identify best practices for ensuring a

continuous reservoir of personnel with a shared commitment to the Toyota Way. The press release

added, Toyota sees human resource training as one of the most vital issues in todays increasingly

challenging age of mega-competition.

The long-term strategic motivation behind the Toyota Way was to identify and develop people who could

work lean and optimize efficiency, in order to support TMCs aggressive push to become the worlds

2

largest automotive manufacturer. TMC executives were well aware that implementing this strategy

would require creating a culture in which employees supported the Toyota Way principles worldwide. As

Toyota reports on its corporate website (http://www.toyota-

global.com/sustainability/stakeholders/employees.html), its fundamental stance on human resource

development is "making things is about developing people. The website also states that Toyotas human

resource development is based on on-the-job training in addition to establishing and improving

educational systems that focus on sharing and conveying appropriate values in accordance with the

Toyota Way.

Putting Principles Into Practice?

The Toyota Ways 14 principles combine a long-term strategic vision with the day-to-day practices that

are designed to make the vision a reality. Several principles and their respective practices are especially

relevant to Toyotas defective floor mat and accelerator mismanagement. The following summary is a

distillation of these principles from Jeffrey Likers book, The Toyota Way. [2004. NY: McGraw-Hill]

Section I: Long-Term Philosophy

Principle 1. Base your management decisions on a long-term philosophy, even at the expense of short-

term financial goals.

Have a philosophical sense of purpose that supersedes any short-term decision making.

Work, grow, and align the whole organization toward a common purpose that is bigger

than making money.

Principle 5. Build a culture of stopping to fix problems, to get quality right the first time.

Quality for the customer drives your value proposition.

Build into your organization support systems to quickly solve problems and put in place

countermeasures.

Build into your culture the philosophy of stopping or slowing down to get quality right the

first time to enhance productivity in the long run.

Section III: Add Value to the Organization by Developing Your People

Principle 9. Grow leaders who thoroughly understand the work, live the philosophy, and

teach it to others.

Grow leaders from within, rather than buying them from outside the organization.

Do not view the leaders job as simply accomplishing tasks and having good people skills.

Leaders must be role models of the companys philosophy and way of doing business.

Good leaders must understand the daily work in great detail so they can be the best

teachers of your companys philosophy.

3

Principle 10. Develop exceptional people and teams who follow your companys philosophy.

Train exceptional individuals and teams to work within the corporate philosophy to

achieve exceptional results. Work very hard to reinforce the culture continually.

Use cross-functional teams to improve quality and productivity and enhance flow by

solving difficult technical problems.

Make an ongoing effort to teach individuals how to work together as teams toward

common goals.

Principle 13. Make decisions slowly by consensus, thoroughly considering all options;

implement decisions rapidly (nemawashi).

Nemawashi is the process of discussing problems and potential solutions with everyone

affected, to collect their ideas and get agreement on how to move forward. This

consensus process is time-consuming but broadens the search for solutions, and once a

decision is made, implementation can move ahead rapidly.

Toyotas elaboration on the Toyota Way principles on the corporate website describe how these

principles support the companys relations with employees.

TMCs Relations with Employees

According to TMCs website (http://www.toyota-global.com/sustainability/stakeholders/employees.html):

The Toyota Way promotes mutual trust and respect between labor and management,

long-term employment stability, and communication.

The Toyota Institute conducts core training for affiliates worldwide, to teach work

methods (problem solving and management expertise), so Toyota personnel around the

world can put the shared Toyota Way into practice.

The May 23, 2011 NAQAP report questioned how effectively Toyota followed the Toyota Way principles.

The criticisms that are most relevant to human resources management reveal flaws in the executive

reporting structure, global communications structure, and safety management accountability.

The North American Quality Advisory Panels Findings

Management and organization analysts generally agree that the oversights that led to Toyotas 2009-

2010 recalls stemmed from Toyota setting its own sights, more than ten years earlier, on becoming the

worlds largest automaker. Critics propose that the companys focus on global expansion superceded

management and employee structures, policies, and processes that the company required in order to

keep balanced tabs on the internal and external environments. The NAQAP concurred, adding, the

root causes of Toyotas recent challenges go beyond the issue of growth. They are more complex and

more subtle, and in many cases, are not unique to Toyota.

Some of the root causes that the NAQAP cited are rooted in what were possibly misguided or

mismanaged human resources strategy and management policies.

4

Executive reporting and decision-making structures

1. According to the NAQAP, Toyota structured its global operations around functional silos, each of

which reported separately to TMC executives in Japan. Decision-making structures that involved

everything from recalls, communications, marketing, and vehicle design and development were centrally

managed and tightly controlled by TMC. In North America, instead of having one chief executive in

charge of all of its divisions (e.g., sales and marketing, general corporate, engineering, and

manufacturing), Toyota placed a separate head in each division, each of whom reported directly to TMC

in Japan.

One-way communications

2. NAQAP suggested that Toyotas global silo structure contributed to problems with yokoten, the part

of Toyotas process of continuous improvement that focuses on sharing best practices and transferring

knowledge across the organization. For example, Toyotas president, Akio Toyoda, said that the

company failed to connect the dots between problems with sticking accelerator pedals in Europe and in

the United States. A Toyota executive admitted to Congress that a weakness in our system has been

that within this company, we didnt do a very good job of sharing information across the globe. Most of

the information was one way. It would flow from the regional markets, like the United States, Canada or

Europe back to Japan. A case in point: in 2000 the United Kingdom recalled Lexus IS-200 models due to

a possibility that the drivers side carpet mat may rotate around the central fixing and interfere with the

operation of the accelerator pedal. Toyota did not report this recall to North America counterparts. Had

North America operations known about the mat and accelerator pedal problem, its specialists could have

examined the related safety design issues before they became a widespread problem.

Safety management responsibility oversight

3. The NAQAP suggested that Toyota viewed safety as a subset of quality. As a result, Toyota did not

have a senior executive level position with overall responsibility for safety, and did not appear to have a

clear management chain of responsibility for safety issues. Although, from Toyotas perspective,

everyone at the company was responsible for safety, the NAQAP suggested that the diffused nature of

this responsibility could have thwarted the companys ability to recognize the need to accept

responsibility when the public raised safety concerns.

Summary

Critics suggest that TMCs strategy of aggressive growth played a significant factor in how the company

mishandled safety concerns raised by U.S. customers who complained that their vehicles accelerator

pedals stuck in an acceleration position. The NAQAP concluded that while they were focusing on global

expansion and becoming the worlds top automotive manufacturer, TMC executive management

(ironically) overlooked the need to redesign the executive reporting and communication structures and

to centralize responsibility for safety, and they ignored key principles of the Toyota Way that would have

led the company to investigate consumers and government regulators complaints sooner.

5

TMCs executives slow response to customers and regulators who raised vehicle safety concerns (until

the media took up the cause) suggests to some critics that Toyota management may have sacrificed

Toyota Way principles to try to save money and face.

Questions and Answers

1) Based on the three big strategic questions of strategic HR (What is our present situation?

Where do we want to go? How do we plan to get there?), and based on the information provided

in this case, how well, in your opinion, did Toyota plan for global expansion back in 2000, in

terms of executive reporting structure and corporate communication procedures? Was the

structure too centralized and vertical, or not centralized and vertical enough? Should the North

American affiliates have had more decision-making autonomy and/or horizontal communication

paths? Should there have been more or fewer horizontal communication paths between different

divisions and/or countries (e.g., England and the U.S.)? Explain your position.

2) What is organizational culture? Was Toyotas response to customer complaints about safety

consistent with the organizational culture that TMC executives desired to promote through the

Toyota Way principles? Address in your response Principles 1, 5, 9 and 13 as described in this

case.

3) Based on what you read in this case regarding executive managers slow response to consumer

complaints about sticking accelerator pedals, how well did managers training from the Toyota

Institute transfer to solving Toyotas real-world safety problem? How might the training they

received be improved to better shape behavior to achieve Principle 5: Build a culture of stopping

to fix problems? Consider types of reinforcement, and the challenges of resistance to change

and strategic congruence.

4) What is your opinion of the Toyota Way principle (#9) of growing (i.e., developing) leaders

from within? How does this principle fit in with the reasoning behind succession planning? If you

were Toyotas director of human resources, would you support this practice or recommend

recruiting leaders from outside the company, or a combination of both? Explain your reasoning.

5) Prepare an other lessons learned assessment from the facts presented in this case that relate

to the human resource function. Include recommended action for each lesson learned. Dont

cover topics addressed in the previous questions.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Toyota Case AnalysisDocument4 paginiToyota Case AnalysisZain-ul- FaridÎncă nu există evaluări

- Best Selction Practice ToyotaDocument3 paginiBest Selction Practice ToyotaManpreet Singh BhatiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment For Managing Financial Resources and Decisions.22490Document9 paginiAssignment For Managing Financial Resources and Decisions.22490vanvitloveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Value ChainsDocument5 paginiGlobal Value ChainsAmrit KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Productivity and Reliability-Based Maintenance Management, Second EditionDe la EverandProductivity and Reliability-Based Maintenance Management, Second EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategy Analysis: Fan ZhangDocument10 paginiStrategy Analysis: Fan ZhangYashu SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective ProcessDocument16 paginiEffective Processajelena83Încă nu există evaluări

- Managing Brand Equity in The Digital Age: Croma's Omni-Channel RetailingDocument1 paginăManaging Brand Equity in The Digital Age: Croma's Omni-Channel RetailingETCASESÎncă nu există evaluări

- NotesDocument7 paginiNoteschady.ayrouthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caux Principles 1Document4 paginiCaux Principles 1Kirti DadheechÎncă nu există evaluări

- Opportunity Cost, Marginal Analysis, RationalismDocument33 paginiOpportunity Cost, Marginal Analysis, Rationalismbalram nayakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internationalisation and Tesco Into AmericaDocument28 paginiInternationalisation and Tesco Into AmericaThomas Clark0% (1)

- 1898 Ford Operations ManagementDocument8 pagini1898 Ford Operations ManagementSanthoshAnvekarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Individual Presentation: International Market Expansion of AstrazenecaDocument12 paginiIndividual Presentation: International Market Expansion of AstrazenecaSami Ur Rehman0% (1)

- BP-Case AnalysisDocument3 paginiBP-Case AnalysisShrey TanejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Singapore PESTLE ANALYSISDocument7 paginiSingapore PESTLE ANALYSISmonikatatteÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbhiDocument4 paginiAbhivaibhavÎncă nu există evaluări

- MM Module 1 A Prelude To The World of MarketingDocument11 paginiMM Module 1 A Prelude To The World of MarketingAbhishek MukherjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Ethics, Stakeholder ManagementDocument17 paginiBusiness Ethics, Stakeholder ManagementRempeyekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Cover SheetDocument10 paginiAssignment Cover SheetShahbaz Meraj100% (1)

- Finance and Marketing: Masters Engineering RoutesDocument44 paginiFinance and Marketing: Masters Engineering RoutesHoàngAnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment - International HRMDocument2 paginiAssignment - International HRMMaryam TariqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership Complexity and Change - Mandhu CollegeDocument13 paginiLeadership Complexity and Change - Mandhu CollegeMohamed AbdullaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature of Innovation: Making The Idea RealityDocument10 paginiNature of Innovation: Making The Idea RealityhuixintehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation Skills ITADocument18 paginiPresentation Skills ITAKelly maria RodriguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motorola CaseDocument2 paginiMotorola CaseMd. Azim HossainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kaizen Final Ass.Document7 paginiKaizen Final Ass.Shruti PandyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Porter's Diamond Model (Analysis of Competitiveness) ...Document2 paginiPorter's Diamond Model (Analysis of Competitiveness) ...BobbyNicholsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Semester: 113 - Fall 2011Document7 paginiSemester: 113 - Fall 2011Manju MohanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3 - Goals Gone Wild The Systematic Side Effects of Overprescribing Goal SettingDocument10 paginiChapter 3 - Goals Gone Wild The Systematic Side Effects of Overprescribing Goal SettingAhmed DahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 3 WESCODocument18 paginiGroup 3 WESCOGaurav ChoukseyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self-Development PortfolioDocument19 paginiSelf-Development Portfolioaries usamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lululemon Submission To Parliamentary Finance CommitteeDocument7 paginiLululemon Submission To Parliamentary Finance CommitteedanieltencerÎncă nu există evaluări

- SM C6 ReportDocument7 paginiSM C6 ReportKshitij vijayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quality & Specifications 09Document12 paginiQuality & Specifications 09AboAdham100100Încă nu există evaluări

- Addisu Individual Assg Mkting2Document7 paginiAddisu Individual Assg Mkting2daniel100% (3)

- Shengsiong 1rijurajDocument7 paginiShengsiong 1rijurajSibi StephanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Blue Ocean StrategyDocument8 paginiThe Blue Ocean StrategybrendaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Porter S Diamond Approaches and The Competitiveness With LimitationsDocument20 paginiPorter S Diamond Approaches and The Competitiveness With Limitationsmmarikar27100% (1)

- HBS Millennium Case AnalysisDocument4 paginiHBS Millennium Case AnalysisDeepak Arthur JacobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Case StydyDocument6 paginiToyota Case Stydytom agazhieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Model Question Paper 302 - E-Business Time: 3 Hours Max.,MarksDocument1 paginăModel Question Paper 302 - E-Business Time: 3 Hours Max.,MarksSarath Bhushan KaluturiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 - The Role of Innovation and Technology in Sustaining The Petroleum and Petrochemical IndustryDocument17 pagini2016 - The Role of Innovation and Technology in Sustaining The Petroleum and Petrochemical Industrykoke_8902Încă nu există evaluări

- UMACRQ-15-M Strategic Management Accounting: Session 6: Activity-Based Costing (ABC) RevisitedDocument24 paginiUMACRQ-15-M Strategic Management Accounting: Session 6: Activity-Based Costing (ABC) RevisitedAhmed MunawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 11 - Strategic Quality and Systems ManagementDocument4 paginiUnit 11 - Strategic Quality and Systems ManagementEYmran RExa XaYdi100% (1)

- Trade War Between US&ChinaDocument21 paginiTrade War Between US&ChinaRosetta RennerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Publications: Planning, and Control, Prentice-Hall, 1967Document32 paginiPublications: Planning, and Control, Prentice-Hall, 1967Huyền VũÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technology ManagementDocument20 paginiTechnology ManagementSWAPNARUN BANERJEEÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.1 - Intro Assessment and StrategyDocument21 pagini1.1 - Intro Assessment and StrategyFadekemi AdelabuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership, Complexity and Change Assignment Examples: Example of An IntroductionDocument6 paginiLeadership, Complexity and Change Assignment Examples: Example of An IntroductionMohammad Sabbir Hossen SamimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competitive AdvantageDocument60 paginiCompetitive AdvantageFibin Haneefa100% (1)

- Ikea PDFDocument51 paginiIkea PDFShivam MathurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Continental Airlines Case StudyDocument7 paginiContinental Airlines Case Studytimduncan801044Încă nu există evaluări

- C18OP Revision - Past Papers and FeedbackDocument9 paginiC18OP Revision - Past Papers and FeedbackVishant KalwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Cover SheetDocument17 paginiAssignment Cover SheetLokesh Kumar50% (2)

- Designing and Managing AndIntegrated Marketing Channels - 149-155Document86 paginiDesigning and Managing AndIntegrated Marketing Channels - 149-155Shashiranjan KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Environmental Concerns in Wine Production An Integrative ReviewDocument11 paginiCritical Environmental Concerns in Wine Production An Integrative Reviewasaaca123Încă nu există evaluări

- Product Line Management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionDe la EverandProduct Line Management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA507Document10 paginiMBA507pheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green Tea Crème Brûlée 抹茶クレームブリュレDocument1 paginăGreen Tea Crème Brûlée 抹茶クレームブリュレpheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case - Euro Disney Disucssion QuestionsDocument1 paginăCase - Euro Disney Disucssion QuestionspheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA 504 Ch8 SolutionsDocument11 paginiMBA 504 Ch8 SolutionspheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CASE05 BlockbusterDocument18 paginiCASE05 BlockbusterpheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BlockbusterDocument2 paginiBlockbusterpheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA 504 Ch9 SolutionsDocument24 paginiMBA 504 Ch9 Solutionspheeyona100% (1)

- Website For Asian Movie, HK Movie, Korean Movie, Indian Movie, JapaneseDocument2 paginiWebsite For Asian Movie, HK Movie, Korean Movie, Indian Movie, JapanesepheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA 504 Ch8 SolutionsDocument11 paginiMBA 504 Ch8 SolutionspheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus (BUS 536)Document9 paginiSyllabus (BUS 536)pheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- N01799857@hawkmail Newpaltz EduDocument4 paginiN01799857@hawkmail Newpaltz EdupheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA 504 Ch5 SolutionsDocument12 paginiMBA 504 Ch5 SolutionspheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

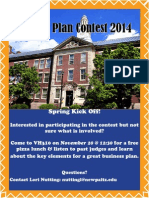

- Business Plan Kickoff ContestDocument1 paginăBusiness Plan Kickoff ContestpheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Business TODAY GBVDocument8 paginiGlobal Business TODAY GBVpheeyona33% (6)

- CASE05 BlockbusterDocument18 paginiCASE05 BlockbusterpheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TNK BP RussiaDocument16 paginiTNK BP RussiapheeyonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Microeco HW Answers Ch. 3, 4Document7 paginiMicroeco HW Answers Ch. 3, 4pheeyona100% (3)

- BP Toyota Case 04-061-2011-4Document16 paginiBP Toyota Case 04-061-2011-4Usman KhalidÎncă nu există evaluări

- NHTSA-UA ReportDocument77 paginiNHTSA-UA ReportJason Jvm VijoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- MGT 210 Toyota Motor Company Case StudyDocument4 paginiMGT 210 Toyota Motor Company Case StudyAbdul Rehman100% (1)

- Toyota Case StudyDocument35 paginiToyota Case StudyInba Thamilan100% (2)

- Audi AG (: Durch Technik, Meaning "Being Ahead Through Technology"Document19 paginiAudi AG (: Durch Technik, Meaning "Being Ahead Through Technology"robertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Did Toyota Work Culture Cause Its ProblemDocument8 paginiDid Toyota Work Culture Cause Its ProblemDanieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Toyota.Document9 paginiFull Toyota.tting_12Încă nu există evaluări

- April 2013 Gears MagazineDocument76 paginiApril 2013 Gears MagazineRodger Bland88% (8)

- SwotDocument4 paginiSwotJB RealizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 028 FGF 15Document392 pagini028 FGF 15Mar StawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Recall AnalysisDocument28 paginiToyota Recall Analysisvarshapatel21100% (3)

- ToyotaDocument3 paginiToyotatori_echoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Global Operations - Unintended Acceleration and Unintended ConsequencesDocument55 paginiToyota Global Operations - Unintended Acceleration and Unintended ConsequencesninemilecoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Under Fire SummaryDocument12 paginiToyota Under Fire SummaryJuan M JaurezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jere Beasley Report - September 2015Document40 paginiJere Beasley Report - September 2015Beasley AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Greenlaw - Toyota Motor Corporation Case StudyDocument16 paginiJohn Greenlaw - Toyota Motor Corporation Case StudyjohngreenlawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Timeline: Toyota From Rise To Recall Crisis, Hearings: DETROIT Mon Feb 22, 2010 9:46pm ESTDocument5 paginiTimeline: Toyota From Rise To Recall Crisis, Hearings: DETROIT Mon Feb 22, 2010 9:46pm ESTtori_echoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marketing Maverics-Toyota's Recall CrisisDocument7 paginiMarketing Maverics-Toyota's Recall Crisissurya mundriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Case StudyDocument11 paginiToyota Case StudyEvelyn KeaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accident Reconstruction Journal May/June 2011Document3 paginiAccident Reconstruction Journal May/June 2011andrewb2005Încă nu există evaluări

- CSP ELT Economic Loss Class Action SettlementDocument11 paginiCSP ELT Economic Loss Class Action Settlementmirageman2Încă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Products Failure Case StudyDocument3 paginiToyota Products Failure Case StudyAfiq AfifeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technology Strategy and Management: Reflections On The Toyota DebacleDocument4 paginiTechnology Strategy and Management: Reflections On The Toyota Debaclevaibhavpardeshi55Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Study: Mitsubushi Montero Sport (Sua)Document5 paginiCase Study: Mitsubushi Montero Sport (Sua)Sharmaine Francisco50% (2)

- Incla DP20001 6158Document22 paginiIncla DP20001 6158Joey KlenderÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Toyota Recall CrisisDocument6 paginiThe Toyota Recall CrisisJason Pang100% (1)

- 6 Speed ShiftingDocument5 pagini6 Speed ShiftingStephen CreanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ob Case Study 2Document6 paginiOb Case Study 2retrobassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Single Pedal Mechanism For Leg Amputated Person and For The Reduction TimeDocument33 paginiSingle Pedal Mechanism For Leg Amputated Person and For The Reduction TimeHariprasath ThangaveluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brand ProjectorDocument277 paginiBrand ProjectorMayank AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări