Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ijo 25 239

Încărcat de

Buzatu IonelTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ijo 25 239

Încărcat de

Buzatu IonelDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Original Article

Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Vol.25 (4), Serial No.73, Oct 2013

Which has a Greater Influence on Smile Esthetics Perception:

Teeth or Lips?

Fahimeh Farzanegan1,*Arezoo Jahanbin2, Hadi Darvishpour3, Soheil Salari3

Abstract

Introduction:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of teeth and lips in the perception of smile esthetics.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty women, ranging between 20 and 30 years of age, all with Class I canine and molar

relationships and no history of orthodontic treatment, were chosen. Five black and white

photographs were taken of each participant in a natural head position while smiling. The most

natural photo, demonstrating a social smile, was selected. Two other photographs were also

taken from a dental frontal view of each subject using a retractor, as well as a lip-together

smile. Three groups of judges including 20 orthodontists, 20 restorative specialists, and 20

laypersons were selected. The judges were then asked to confirm the esthetics of each picture

on a visual analogue scale. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Pearson correlation test

were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

For the orthodontists group, correlation between the scores given to the full smile and each of

its components was significant (=0.05), with equal correlation of each component with the

full smile. In contrast to laypersons, the correlation between the scores given to the full smile

and each of its components among restorative specialists was significant.

Conclusion:

For orthodontists and restorative specialists, esthetic details and the components of the smile

(teeth and perioral soft tissues) were important in esthetics perception. In contrast, laypersons

perceived no effect of esthetics detail or smile components.

Keywords:

Orthodontics, Smile, Esthetics

Received date: 10 Dec 2012

Accepted date: 15 May 2013

Dental Material Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Dental Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

3

Orthodontist, Tehran, Iran.

*Corresponding Author

Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Park square, Mashhad, Iran.

Tel:00989151107306; Fax:00985118829500; E- mail: Jahanbina@mums.ac.ir

2

239

Farzanegan F, et al

Introduction

There are numerous factors contributing to

smile esthetics. In fact, the upper and lower

lips make a frame around the teeth, gingiva,

and the oral cavity to form the overall smile

parameters. In previous studies, the effects of

lip shape (1), smile style (2,3), smile index

(4,5), amount of inciso gingival show of the

teeth (69), golden proportion (10,11), smile

arc (7,10,1214), and width of buccal

corridors (5,10,1517) on smile esthetics

have been thoroughly evaluated, but there is

currently no unanimity concerning the effects

of special factors on producing a beautiful

smile among these studies.

The question of whether the soft tissue of

the lips and perioral or the teeth and gingiva

visible in the smile have a more important

role in smile esthetic perception was the basis

of this study. The judgments of laypersons

and restorative specialist groups were

included to provide comparisons between

orthodontists and other groups of judges

concerning what constitutes a pleasing smile.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to

evaluate the effect of hard and soft tissues of

the oral and perioral region on smile esthetic

perception.

Materials and Methods

Thirty women ranging between 20 and 30

years of age were enrolled in this case-control

study. All subjects were normal occlusion

females from the Mashhad Dental School

with Class I molar and canine relationships

and good anterior alignment who volunteered

to be photographed while smiling. The

subjects had no history of orthodontic

treatment, no significant skeletal asymmetry,

no anterior or posterior crossbite, and no

missing or malformed anterior teeth. This

study was approved by the University of

Mashhad Ethics Committee, and all subjects

provided their written informed consent.

Photographs were taken using a digital

camera (Panasonic Z30) with a Lumix lens.

The distance between the photographic

equipment and the subjects was 150 cm.

After the subject's head was oriented into

the natural head position, 5 photos were taken

of each subject while smiling choose allow an

unforced, natural smile to be selected. In

addition, we took one photograph from

dental frontal view of each subject using a

retractor, as well as a lip-together smile

photograph (Figs: 1,2,3). The subjects wore

a head scarf in order to help the judges focus

on the face rather than other extraneous

features such as hair and neck shape. Thus,

30 images of the full smile, 30 of the liptogether smile, and 30 of the frontal view of

dentition were taken.

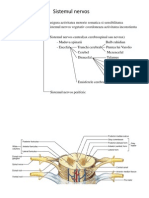

Fig 1: Full smile photograph

Fig 2: Lip-together smile photograph

Fig 3: Frontal view of dentition photograph

240 Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology , Vol.25(4), Serial No.73, Oct 2013

The Role of Lips and Teeth in Smile Esthetic Perception

After downloading directly from the digital

camera to the computer, the digital images

were changed to black and white and

converted into slides using PowerPoint

software for projection onto a large screen.

The evaluating panel consisted of 20

orthodontists, 20 restorative specialists, and

20 laypersons. Each group consisted of 10

men and 10 women ranging in age from 28 to

50 years. The male: female ratio was

maintained at 1:1 in order to eliminate a

gender bias. The raters were told that they

would see 90 slides. They were asked to rate

the attractiveness of the smiles on a 100-point

scale, in which 0 demonstrated the ugliest and

100 the most beautiful form. The raters were

shown each of the 90 slides in a random order

for 15 s. Each rater made his or her

evaluation privately, having no information

about the subjects. Panel members were

asked to re-evaluate the entire sample 5

weeks later.

The second evaluation by the panel

members was found to be in the range of

good repeatability (P= 0.83). An analysis of

variance (ANOVA) and the Pearson correlation

test were used for data analysis. In all

statistical analyses, a P-value of less than 0.05

was considered statistically significant.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the mean scores of the

raters relating to teeth, lips, and full smiles

were 53.12 10.68, 51.87 14.70, and 52.74

13.07, respectively. The ANOVA revealed

that there were no significant differences

between mean scores of lips, teeth, and full

smiles (P=0.930).

Table 1: Mean esthetic scores made by all

judges (N=60) for the Teeth, Lips and Full

Smile

Mean

(SD)

Teeth

Lips

Full Smile

53.12

10.68

51.86

14.70

52.74

13.07

Differences between the scores P-value (ANOVA) = 0.930

Table. 2 shows the individual mean scores

of lips, teeth, and full smiles for orthodontists,

restorative specialists, and laypersons. The

ANOVA revealed there were no significant

differences among the three groups in

evaluating teeth (P=0.135) and lips

(P= 0.466); however, the difference between

raters for full smiles showed a significant

difference (P=0.018). The scores of the

orthodontist were lowest and those of the

laypersons were highest.

Table 2: Mean esthetic scores made by Orthodontists (N=20), Restorative Specialists (N=20) and

Laypersons (N=20) for the Teeth, Lips and Full Smile.

Mean Teeth Score

(SD)

Mean Lips Score

(SD)

Mean Full Smile Score

(SD)

Orthodontists

Restorative

47.73 9.86

47.44 10.95

44.44 10.95

Specialists

54.80 10.89

55.66 16.83

53.41 16.63

Laypersons

56.83 10.07

52.53 15.75

60.37 3.50

0.135

0.466

0.018

P-value (ANOVA)*

*Differences between the scores of the 3 groups of judges

Table. 3 shows that the correlation between

the scores given by orthodontists to the full

smile and each of its components was

significant (=0.05), and the amount of

correlation of each component with the full

smile was equal to 0.660 for teeth and lips.

Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 25(4), Serial No.73, Oct 2013 241

Farzanegan F, et al

In addition, the table shows the correlation

between the scores given to the full smile

and each of its components (teeth and lips)

in restorative specialists ( = 0.01, r =0.847,

and r= 0.860 respectively). For laypersons

there was no statistically significant

correlation between the scores given to the

full smiles and its components. Considering

all raters, the correlation between the scores

given to the full smile and teeth (0.680) was

higher than the correlation between the full

smile and lips (0.606).

Table 3:Correlation between the esthetic scores for the Full Smile and the Teeth and Lips.( Full Smile)

Orthodontists

(N=20)

Restorative Specialists

(N=20)

Laypersons

(N=20)

All judges

(N=60)

Teeth

0.660*

0.847**

-.0.030

0.680**

Lips

0.660*

0.860**

0.066

0.606**

Pearson Correlation Test** Correlation significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)*Correlation significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Discussion

As harmony and balance are not fixed

concepts, standards of beauty can vary

among people with different ethnicity (9).

This study was designed to define the effect

of smile components on the perception of

smile esthetics among 20 to 30 year-old

Iranian females, who had a normal

occlusion. The judges panel consisted of 20

orthodontists, 20 restorative specialists, and

20 laypersons. This study, contrary to other

similar ones, did not investigate the details

of a smile, such as buccal corridors (5,10,

1517), smile arc (7,10,1214), smile line

(69), the shape of the teeth (21,23), golden

proportion (10,11), and their effect on the

perception of smile esthetics. Instead each

smile was divided into two parts; the lips

and the teeth (and gingiva); and the impact

of each part was assessed on the total

perception of smile esthetics.

The result of this study showed that the

highest mean score given by the raters was

for teeth (53.12 10.68), while the lowest

was for lips (51.86 14.70). There was no

significant difference between them the

highest and lowest scores. This could be

explained by the fact that in this study, judges

assessed black and white photographs.

Elimination of beauty factors such as skin,

teeth, and gingiva color could affect the

judges' ratings, possibly making it difficult

for them to accurately rate black and white

photographs. For this reason, all the

photographs were scored at approximately

50% based on the visual analog scale

(VAS). It is possible that most of the judges

needed access to a greater number of beauty

factors in order to rate a profile as excellent.

In addition, this investigation showed in that

contrast to a full smile, there was good

agreement across the orthodontists, restorative

specialists, and laypersons concerning teeth and

lips. This study showed that laypersons

scored smile the highest and orthodontists the

lowest. In previous studies, Johnson and

Smith and Kokich et al. also found that dental

professionals were more sensitive to minor

dental defects than laypersons (15,22).

Among the three groups, restorative

specialists scored a higher correlation

between the components of smile esthetics

and the beauty of the total smile. Even

though the difference of the correlations of

components and full smile was very small

(0.847 vs. 0.860), this may be because

restorative specialists have to pay close

attention to detail in their small delicate

operative field of work. This therefore

makes them better at appraising the

components of a smile and evaluating the

effect of each one separately.

242 Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 25(4), Serial No.73, Oct 2013

The Role of Lips and Teeth in Smile Esthetic Perception

The orthodontists group rated the second

highest degree of correlation. In this group

the correlation coefficient between the

components of a smile and the full smile

was also significant but lower than in the

previous group. This can be explained by the

fact that although the orthodontists appraised

the components of the smile, their attention

to detail was lower than for the restorative

specialists because of their different working

field. Since orthodontists work in the

broader orofacial field, they deal with the

teeth within the totality of the face. They

therefore pay less attention to the fine details

important to operative dentists.

The level of education of the participants in

the layperson group ranged from a high

school diploma to an MS, and no one had a

degree related to medical sciences. Lack of

correlation between the perception of the

beauty of the components and the full smile

in this group demonstrates that laypersons do

not observe the details of smiles, with the

most important issue for them being the full

smile. Furthermore, the separate pictures of

the teeth and lips were meaningless to them,

in contrast to the other groups, and they could

not establish a connection between those

pictures and the full smile of the same person.

For all the raters, the correlation between

the scores given to the full smile and teeth

(0.680) was higher than the correlation

between the full smile and lips (0.606).

Although the difference was small, this

could explain that for all raters, irrespective

of their education and specialization, the

teeth may be more important than the lips in

the esthetic perception of full smile.

Until now, no similar study focusing on

separating the components of the smile has

been reported. Previous studies mostly

considered the details of the smile, such as

the buccal corridors (5,10,1517), smile arc

(7,10,1214), smile line (68), and shape of

the teeth (21,23), for example, on the total

perception of the smile. Unlike this study,

the studies which used different judging

groups to evaluate the smile showed no

difference among the groups, including the

study reported by McNamara et al., which

was performed to find the effects of hard

tissue (cephalometric) and soft-tissue

elements on smile esthetics. In that study

there was also a panel of judges consisting of

laypersons and orthodontists, and they

concluded that the attitudes of the

orthodontists and laypersons were consistent

(r=0.93) (24).

In another research accomplished by

Schabel et al. (19) there was no statistically

significant difference between the attitudes

of the orthodontists and the patients parents

toward smile esthetics. An interesting point

in that study was that no objective

measurement was capable of predicting the

beauty or lack of beauty of a smile.

This study showed there was no statistically

significant correlation between the scores

given to the full smile and its components for

the layperson group. Combining the scores

for the three judging groups together, there

was no significant correlation between the

ratings of the tooth, lips, and the overall

smile.

Providing an ideal treatment has always

been a duty for all specialists, including

orthodontists, but this is not feasible in some

situations due to the anatomical, physiological, and economic conditions of the

patients. As it can be seen from this study,

laypersons exhibit less attention to detail than

specialists.

Conclusions

The role of teeth and lips in the esthetics

perception of smile was similar for

orthodontists. Restorative specialists are

more influenced by the lips than the teeth.

In contrast, laypersons failed to perceive

the esthetics details and component of the

smile. By considering all the evaluation of

all raters, the role of the teeth seems more

important than that of the lips in making a

beautiful smile.

Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 25(4), Serial No.73, Oct 2013 243

Farzanegan F, et al

References

1. Fanous N. Aging lips. Esthetic analysis and

correction. Facial Plast Surg 1987; 4(3):11620.

2. Philips E. The anatomy of a smile. Oral Health

1996; 86(8):79.

3. Philips E. The classification of smile patterns. J Can

Dent Assoc 1999; 65(5): 2524.

4. Ackerman MB. Digital video as a clinical tool in

orthodontics: dynamic smile analysis and design in

diagnosis and treatment planning. In: McNamara JA Jr,

editor.Information technology and orthodontic

treatment. Monograph 40. Craniofacial Growth Series.

Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development;

University of Michigan; 2003. p.195203.

5. Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile

visualization and quantification: part 1. Evolution of

the concept and dynamic records for smile capture.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop2003; 124 (1):412.

6. Robbins JW. Differential diagnosis and treatment

of excess gingival display. Pract Periodontics Aesthet

Dent 1999; 11(2): 26572.

7. Sarver DM. The importance of incisor positioning

in the esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2001; 120(2): 98111.

8. Hunt O, Johnston C, Hepper P, Burden D,

Stevenson M. The influence of maxillary gingival

exposure on dental attractiveness ratings. Eur J

Orthod 2002; 24(2): 199204.

9. Jahanbin A, Pezeshkirad H. The effect of upper lip

height on smile esthetics perception in normal

occlusion and non extraction orthodontically treated

females. Indian J Den Res 2008; 19(3): 2047.

10. Blitz N. Criteria for success in creating beautiful

smiles. Oral Health 1997; 87(12): 3842.

11. Snow SR. Esthetic smile analysis of maxillary

anterior tooth width: the golden percentage. J Esthet

Dent 1999; 11(4): 17784.

12. Hulsey CM. An esthetic evaluation of lip-teeth

relationships present in the smile. Am J Orthod 1970;

57(2): 13244.

14. Zachrisson BU. Esthetic factors involved in

anterior tooth display and the smile: vertical

dimension. J Clin Orthod 1998; 35(7): 43245.

15. Johnson DK, Smith RJ. Smile esthetics after

orthodontic treatment with and without extraction of

four first premolars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

1995; 108(2): 1627.

16. Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and

design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod 2002; 36(4):

22136.

17. Moore T, Southard KA, Casko JS, Gian F,

Sounthatd TE. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005; 127(2): 20813.

18. Frindel F. The unattractive smile or 17 keys to the

smile. Orthod Fr. 2008; 79(4): 27381.

19. Schabel BJ, Franchi L, Bacctti T, Mcnamara jr

JA. Subjective vs objective evaluations of smile

esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;

135(4): 729.

20. Gul-e-Erum, Fida M. Changes in smile parameters

as perceived by orthodontists, dentists, artists, and

laypeople. World J Orthod. 2008; 9(2): 13240.

21. Anderson KM, Behrents RG McKinney T,

Buschang PH. Tooth shape preferences in an esthetic

smile. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;

128(4): 45865.

22. Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing

the perception of dentists and lay people to altered

dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent 1999; 11(6): 31124.

23. Heravi F, Rashed R, Abachizadeh H. Esthetic

preferences for the shape of anterior teeth in a posed

smile. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139(6):

80614.

24. McNamara L, McNamara JA Jr, Ackerman MB,

Baccetti T. Hard- and soft-tissue contributions to the

esthetics of the posed smile in growing patients

seeking orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2008; 133(4): 4919.

244 Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 25(4), Serial No.73, Oct 2013

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Franchini Judo Active Recovery EJAP 2009Document7 paginiFranchini Judo Active Recovery EJAP 2009Buzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Cls I KenDocument13 paginiCls I KenBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- J 1600-0765 2010 01335 XDocument5 paginiJ 1600-0765 2010 01335 XBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Specificatii Tractoare Seria 5Document2 paginiSpecificatii Tractoare Seria 5David Paul ClaudiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Cls II KenDocument10 paginiCls II KenBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Unconventional Prosthodontics: Post, Core and Crown TechniqueDocument5 paginiUnconventional Prosthodontics: Post, Core and Crown TechniqueBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- A New Design For Anterior Fixed Partial Denture, Combining Facial Porcelain and Lingual Metal PTU Type IIDocument5 paginiA New Design For Anterior Fixed Partial Denture, Combining Facial Porcelain and Lingual Metal PTU Type IIBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- 99 Ppav 11 N 1 P 95Document13 pagini99 Ppav 11 N 1 P 95Buzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2010 Oral Health Systems in EuropeDocument28 pagini2010 Oral Health Systems in EuropeBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- CancerDocument10 paginiCancerBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Jap 4 109Document7 paginiJap 4 109Buzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Fisa Observatie ProteticaDocument5 paginiFisa Observatie ProteticaBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Regression MethodsDocument7 paginiRegression MethodsBuzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- 10.1007 - s13191 011 0046 0Document7 pagini10.1007 - s13191 011 0046 0Rivemi GusyantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Maduva Spinarii. Trunchiul Cerebral. CerebelDocument35 paginiMaduva Spinarii. Trunchiul Cerebral. CerebelI.m. DanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Jap 4 97Document6 paginiJap 4 97Buzatu IonelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maduva Spinarii. Trunchiul Cerebral. CerebelDocument35 paginiMaduva Spinarii. Trunchiul Cerebral. CerebelI.m. DanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3 Extra Practice ProblemsDocument2 paginiChapter 3 Extra Practice ProblemsSomin LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Foundations of Business Analytics Vnuk - FbaDocument44 paginiFoundations of Business Analytics Vnuk - FbaTịnh NguyênÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of 5S On Employee Performance: An Empirical Study Among Lebanese HospitalsDocument7 paginiThe Effect of 5S On Employee Performance: An Empirical Study Among Lebanese HospitalsMuthu BaskaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scikit - Notes MLDocument12 paginiScikit - Notes MLVulli Leela Venkata Phanindra100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- American J Political Sci - 2023 - Eggers - Placebo Tests For Causal InferenceDocument16 paginiAmerican J Political Sci - 2023 - Eggers - Placebo Tests For Causal Inferencemarta bernardiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standardizing Six Sigma Green BELT TrainingDocument19 paginiStandardizing Six Sigma Green BELT TrainingKATY lORENA MEJIA PEDROZOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationship of Learning Motivation and Learning Environment With The Learning Achievements of Students of Tata Boga Unnes-Education As A Form of Evalusion of MBKM Program in 2021Document9 paginiRelationship of Learning Motivation and Learning Environment With The Learning Achievements of Students of Tata Boga Unnes-Education As A Form of Evalusion of MBKM Program in 2021Ime HartatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quant ExamDocument13 paginiQuant ExamhootanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 LinearRegressionDocument61 pagini04 LinearRegressionjoselazaromrÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Consumer Buying Behaviour Towards Agriculture Inputs - An Empirical Study in Rural Area of BardoliDocument2 paginiConsumer Buying Behaviour Towards Agriculture Inputs - An Empirical Study in Rural Area of BardoliManoj Bal100% (1)

- International Standard: Statistical Interpretation of Data - Median - Estimation and Confidence IntervalsDocument6 paginiInternational Standard: Statistical Interpretation of Data - Median - Estimation and Confidence IntervalsyanelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Craps Monter Carlo Simulation Model (Davis-Flood)Document9 paginiCraps Monter Carlo Simulation Model (Davis-Flood)Ian DavisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Science and Machine Learning A Survey On The Future Revenue Predictions and The Amount of Product SalesDocument8 paginiData Science and Machine Learning A Survey On The Future Revenue Predictions and The Amount of Product SalesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Probit and LogitDocument35 paginiProbit and LogitArjunsinh RathavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collaboration Trumps Competition in High-Tech Project Teams: Michel AvitalDocument23 paginiCollaboration Trumps Competition in High-Tech Project Teams: Michel Avitalo835625Încă nu există evaluări

- 22 05 2019 COGE FinalDocument36 pagini22 05 2019 COGE FinalMohammed Chakib BEDJAOUIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aaron Brown: StatistiksDocument4 paginiAaron Brown: StatistiksMbrebes MilehÎncă nu există evaluări

- BTTM Question BankDocument2 paginiBTTM Question BankVivekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poster AbstractsDocument273 paginiPoster AbstractsCernei Eduard Radu0% (1)

- Chapter 01 Test Bank - Version1Document19 paginiChapter 01 Test Bank - Version1lizarrdoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heart Disease Prediction System Using Naive Bayes: Dhanashree S. Medhekar, Mayur P. Bote, Shruti D. DeshmukhDocument5 paginiHeart Disease Prediction System Using Naive Bayes: Dhanashree S. Medhekar, Mayur P. Bote, Shruti D. DeshmukhMeenakshi SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision TreesDocument19 paginiDecision TreesMuhammad Zain AbbasÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 9Document8 paginiCH 9Maulik ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Lecure 5 (Sampling Distribution)Document24 paginiLecure 5 (Sampling Distribution)Carlene UgayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Statistics Mock Exam: Duration: 3 Hours Max. Marks: 50 Section A: Mcqs (20 Marks)Document7 paginiIntroduction To Statistics Mock Exam: Duration: 3 Hours Max. Marks: 50 Section A: Mcqs (20 Marks)Ahsan KamranÎncă nu există evaluări

- STA630 QuizDocument2 paginiSTA630 QuizIT Professional0% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S209012321200104X MainDocument7 pagini1 s2.0 S209012321200104X Mainakita_1610Încă nu există evaluări

- Basic Statistical Tools in Research and Data AnalysisDocument8 paginiBasic Statistical Tools in Research and Data AnalysisMoll22Încă nu există evaluări

- A Complete Tutorial Which Teaches Data Exploration in Detail PDFDocument18 paginiA Complete Tutorial Which Teaches Data Exploration in Detail PDFTeodor von BurgÎncă nu există evaluări

- BiasDocument17 paginiBiasRanda IlhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe la EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (81)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDe la EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (6)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe la EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (404)