Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Partnership Reviewer

Încărcat de

racrabe96Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Partnership Reviewer

Încărcat de

racrabe96Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Partnership Reviewer

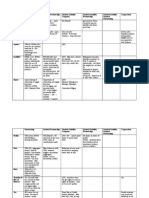

Prof. Roberto Dio

2D; Sem. 2, 2009-2010

I.

NATURE; CREATION

A.

Definition; essential features

Kinds of Organizations:

(1)

Sole proprietorship has a business name;

only one individual

(2)

Partnership partnership name; separate

personality; 2 or more individuals

(3)

Corporation Corporate name; separate

personality; multiple owners (not limited to

individuals)

(4)

Trusts

(5)

Associations

Requisites of a Partnership:

(1)

Two or more persons bind themselves to

contribute money, property or industry to a

common fund (even if there is no actual

contribution as long as there is an agreement to

contribute).

(2)

Intention to divide the profits among

themselves (profits and losses)

Industry work, i.e., any activity of the human body; it

actually pertains to future industry

(a) time rendered

(b) idea

(c) service rendered

Features of a partnership: (Quiz)

(1)

Partnership name

(2)

Joint interest (Common fund)

(3)

Joint management and control

(4)

Mutual agency

(5)

Business for profit

Purpose: to engage in a commercial or business

transaction (there is the element of habituality)

Cause: The undertaking to contribute

Object: Must be lawful

- Unlawful objects: (1) Prohibited by law (RPC);

(2) Those not penal in nature but prohibited by law

B.

Creation

AGAD vs. MABATO (1968)

- A partnership may be constituted in any form, except

where immovable property or real rights are

contributed thereto, in which case a public instrument

shall be necessary (Art. 1771).

- A contract of partnership is void, whenever

immovable property is contributed thereto, if inventory

of said property is not made, signed by the parties, and

attached to the public instrument (Art. 1773).

- In the case at bar: The partnership was established to

operate a fishpond and not to engage in a fishpond

business. Neither said fishpond nor a real right

thereto was contributed to the partnership by any one

of the partners or became part of the capital thereof,

even if a fishpond or a real right thereto could become

part of its assets. Art. 1773 is NOT applicable.

TORRES vs. CA (1999)

Quick facts: Partnership entered into for the purpose of

developing land into subdivision; but their venture

failed. Petitioner sisters contributed the land,

Respondent Torres contributed his industry and

advanced the expenses and costs.

- Petitioners contend that the contract is void because

there was no inventory of the land, citing Art. 1773.

Ratio: (1) Art. 1773 was intended primarily to protect

third persons.

- SC cited Tolentino: the execution of the public

instrument would be useless if there is no inventory of

the property contributed, because without its

designation and description, they cannot be subject to

inscription in the Registry of Property, and their

contribution cannot prejudice third persons. Thus, the

contract is declared void by the law when no such

inventory is made.

- THE CASE AT BAR DOES NOT INVOLVE THIRD

PARTIES WHO MAY BE PREJUDICED.

(2) Petitioners cannot in one breath deny the contract

and in another recognize it to be able to claim from

Torres the 60% of the value of the property.

- The alleged nullity of the partnership will not prevent

courts from considering the JVA an ordinary contract

from which the parties rights and obligations to each

other may be inferred and enforced.

ARBES vs. POLISTICO (1929)

- There is no question that Turnuhan Polistico & Co. is

an unlawful partnership.

- A partnership must have a lawful object and must be

established for the common benefit of the partners.

When the dissolution of an unlawful partnership is

decreed, the profits shall be given to charitable

institutions

(1) As to profits:

- To be able to receive the profits, the partners to an

unlawful partnership would have to base his action on

the contract which is VOID and NON EXISTENT.

- It would be immoral and unjust for the law to permit

a profit from an industry prohibited by it.

(2) As to contributions:

- Since the contract is void, there is no reason for the

administrator of the Partnership to retain the

contribution of the others without any consideration

because there is NO CONTRACT; for which reason he is

bound to return it, and he who has paid his

contribution is bound to recover it.

- Court applied concept of unjust enrichment

BAUTISTA (on ARBES vs. POLISTICO CASE):

- Court should have applied:

Art. 1411. When the nullity proceeds from the

illegality of the cause or object of the contract, and the

act constitutes a criminal offense, both parties being in

pari delicto, they shall have no action against each

other, and both shall be prosecuted. Moreover, the

provisions of the Penal Code relative to the disposal of

effects or instruments of a crime (forfeited in favor of

the State) shall be applicable to the things or the price

of the contract.

Art. 1412. If the act in which the unlawful or

forbidden cause consists does not constitute a criminal

offense, the following rules shall be observed: (1) When

the fault is on the part of both contracting parties,

neither may recover what he has given by virtue of the

contract, or demand the performance of the other's

undertaking;

- Thus the contributions should not have been

returned to the contributors, but should have been

confiscated in favor of the State. The contributors must

be presumed to have known the criminal nature of the

object of the partnership they agreed to form, and

should have thus been prosecuted and convicted for

running a gambling joint. (Bautista, p. 19)

Notes:

PROCEDURE to establish a PARTNERSHIP where

immovables are contributed:

(1)

Purpose

(2)

Contribution

(3)

Division of Profits

(4)

AOP: have it notarized

(5)

Inventory: make, sign and attach

(6)

Register with SEC

(7)

Deed of Sale (to transfer ownership of

the immovable property from the partner who

originally owns it to the partnership).

ART. 1811

- Common fund DOES NOT EQUATE TO co-ownership,

only co-possession.

- The partnership owns the property because it has its

own

juridical

personality

apart

from

its

members/partners, thus there is no co-ownership.

- Co-possession is limited to partnership purposes and

for the pursuance of the ordinary business of the

partnership.

TOCAO vs. CA (2000)

- A contract of P. is consensual; an oral contract of P is

as good as a written one. Where no immovable property

or real rights are involved, what matters is that the

parties have complied with the requisites of a

partnership.

- The partnership has a juridical personality separate

and distinct from that of each of the partners, even in

case of failure to comply with the requirements of Art.

1772, first paragraph (Capital of 3K and up public

instrument & registered with SEC).

- The best evidence of the existence of the partnership,

which is not yet terminated (though in the winding up

stage), are the unsold goods and uncollected

receivables still in the possession of Tocao. (Her right to

possess the goods of the partnership proved that she

was a partner/co-possessor.)

- A mere falling out or misunderstanding between

partners does not convert the partnership into a sham

organization the partnership exists until dissolved

under the law.

- Any one of the partners may, at his sole pleasure,

dictate a dissolution of the partnership at will, though

he must, however, act in good faith, not that the

attendance of bad faith can prevent the dissolution of

the P but that it can result in a liability for damages.

- The right to choose with whom a person wishes to

associate is the very foundation and essence of a P. It

continued existence is dependent on the constancy of

that mutual resolve.

- Doctrine of delectus personae: allows the partners to

have the power, not necessarily the right to dissolve the

P.

- The partnership continues even after dissolution for

the purpose of winding up the business.

C.

Separate Juridical Personality

AGUILA vs. CA (1999)

- A partnership has a juridical personality separate

and distinct from that of each of the partners it is the

partnership, not its officers or agents, which should be

impleaded in any litigation involving property registered

in the name of the P.

- The partners cannot be held liable for the obligations

of the P unless it is shown that the legal fiction of a

different juridical personality is being used for

fraudulent, unfair, or illegal purposes.

TAN vs. DEL ROSARIO (1994)

- A general professional partnership, unlike an

ordinary business partnership (which is treated as a

corporation for income tax purposes and thus subject

to corporate income tax), is not of itself an income tax

payer. The income tax is imposed not on the

professional P, which is tax exempt, but on the

partners themselves in their individual capacity

computed on their distributive shares of partnership

profits.

- There is no distinction in income tax liability between

a person who practices his profession alone or

individually and one who does it through a

partnership.

- Partnerships are either: (1) taxable Ps, or (2) exempt

Ps. A general profession P falls under (2).

MENDIOLA vs. CA (2006)

- In a partnership, members become co-owners (copossessors) of what is contributed to the firm capital

and of all the property that may be acquired thereby.

Each partner possesses a joint interest in whole

partnership property.

- If the relation does not have this feature, it is not one

of partnership.

- In this case, the parties merely shared profits. This

alone does not make a partnership.

- A corporation cannot become a member of a

partnership in the absence of express authorization by

statute or charter. 2 reasons:

(1) The mutual agency between the partners, whereby

the corporation would be bound by the acts of persons

who are not its duly appointed and authorized agents

and officers, would be inconsistent with the policy of

the law that the corporation shall manage its own

affairs separately and exclusively;

(2) Such an arrangement would improperly allow

corporate property to become subject to risks not

contemplated by the stockholders when they originally

invested in the corporation.

ANGELES vs. Sec. of Justice (2005)

- Mere failure to register the contract of partnership

with the SEC does not invalidate a contract that has

the essential requisites of a P. The purpose of

registration of the contract of P is to give notice to third

persons. Neither does such failure to register affect the

Ps juridical personality.

A P may exist even if the partners do not use the

words partner or partnership.

- Sosyo industrial Industrial partnership

D. Mutual Agency: Partners in a partnership are

mutual agents and principals of each other.

E. Distinguish Partnership from:

1) Co-ownership; Co-possession

- There is no co-ownership in partnership because it is

the partnership which owns the property.

2) Tenancy in common; joint tenancy

- Joint tenancy is co-possession, and tenancy in

common is co-ownership.

3) Joint Ventures

- Joint ventures are generally concerned with an

isolated transaction or project, as opposed to a

partnership which contemplates a general business

with some continuity. Moreover, a joint venture does

not have a firm name, there is no mutual agency, and it

does not have a separate juridical personality.

4) Joint Adventures

5) Joint Accounts; Cuentas en Participacion

- A partnership constituted in such a manner, the

existence of which was only known to those who had

an interest in the same, there being no mutual

agreements between the partners, and without a

corporate name indicating to the public in some way

that there were other people besides the one who

ostensibly managed and conducted the business, is

exactly the accidental partnership of cuentas en

participacion. (Bourns vs. Carman)

6) Agency

- There is no mutual agency in that the agent is only

the agent, and is not likewise the principal of his

principal. There is also no common fund in agency.

Art. 1769. In determining whether a partnership

exists, these rules shall apply:

(1) Excepts as provided by Article 1825, persons who

are not partners as to each other are not partners as to

third persons;

(2) Co-ownership or co-possession does not of itself

establish a partnership, whether such co-owners or copossessors do or do not share any profits made by the

use of the property;

(3) The sharing of gross returns does not of itself

establish a partnership, whether or not the persons

sharing them have a joint or common right or interest

in any property from which the returns are derived;

(4) The receipt by a person of a share of the profits of a

business is prima facie evidence that he is a partner in

the business, but no such inference shall be drawn if

such profits were received in payment:

a. As a debt by installments or otherwise;

b. As wages of an employee or rent to a landlord;

c. As an annuity to a widow or representative of a

deceased partner;

d. As interest on a loan, though the amount of

payment vary with the profits of the business;

e. As the consideration for the sale of a goodwill of a

business or other property by installment or otherwise.

Sir: The list is not exclusive

Art. 1825. When a person, by words spoken or written

or by conduct, represents himself, or consents to

another representing him to anyone, as a partner in an

existing partnership or with one or more persons not

actual partners, he is liable to any such persons to

whom such representation has been made, who has,

on the faith of such representation, given credit to the

actual or apparent partnership, and if he has made

such representation or consented to its being made in

a public manner, he is liable to such person whether

the representation has or has not been made or

communicated to such person so giving credit by or

with the knowledge of the apparent partner making the

representation or consenting to its being made:

(1) When a partnership liability results, he is liable as

though he were an actual member of the

partnership;

(2) When no partnership liability results, he is liable

pro rata with the other persons, if any, so

consenting to the contract or representation as to

incur liability, otherwise separately.

When a person has been thus represented to be a

partner in an existing partnership, or with one or more

persons not actual partners, he is an agent of the

persons consenting to such representation to bind

them to the same extent and in the same manner as

though he were a partner in fat, with respect to

persons who rely upon the representation. When all

the members of the existing partnership consent to the

representation, a partnership act or obligation results;

but in all other cases it is the joint act or obligation of

the person acting and persons consenting to the

representation.

therein, who shall also have no right against the third

person who contracted with the manager, unless the

latter formally cedes his rights to them.

Art. 243. The liquidation shall be made by the manager

who, upon the conclusion of the transactions, shall

render a verified account of their results.

SEC OPINION [February 29, 1980]

[NOTE: This is only a summary of the article, but I

think these are the important parts.=)]

CODE OF COMMERCE

Title II: Joint Accounts

Art. 239. Merchants may interest themselves in the

transaction of other merchants, contributing thereto

the part of the capital they may agree upon, and

participating in the favorable or unfavorable results

thereof in the proportion they may determine.

Art. 240. In their formation, joint accounts shall not be

subject to any formality, and may be privately

contracted orally or in writing, and their existence may

be proved by any of the means recognized by law

(according to the provisions of Article 51).

Art. 241. In the transactions referred to by the two

preceding articles, no commercial name common to all

the participants can be adopted, nor can any further

direct credit be used than that of the merchant who

makes and directs them in his name and under his

individual responsibility.

Art. 242. Those who contract with the merchant who

carries on the business shall have a right of action

against him only and not against the others interested

A corporation cannot ordinarily enter into a

contract of partnership with another corporation or

individual.

The limitation is based on public policy, since in a

partnership the corporation would be bound by the

acts of persons who are not duly appointed and

authorized agents and officers, which would be

entirely inconsistent with the policy of the law that

a corporation shall manage its own affairs,

separately and exclusively.

In entering into a partnership, the identity of the

corporation is lost or merged with that of another.

Remember that a corporation can act only through

its duly authorized agents and is not bound by the

acts of anyone else.

EXCEPTIONS to the application of this general rule

may be allowed PROVIDED the following conditions

are met:

o The articles of incorporation of the

corporations involved must expressly authorize

the corporation to enter into contracts of

partnership with others in the pursuit of its

business;

o The agreement or article of partnership must

provide that all the partners will manage the

partnership; and

o The articles of partnership must stipulate that

all the partners are and shall be jointly and

severally liable for all the obligations of the

partnership.

Moreover, two or more corporations may enter into

a joint venture/consortium if the nature of the

venture is in line with the business authorized by

its charter. BUT note that no independent legal

entity is borne out of it and the same need not be

registered with the Commission.

GATCHALIAN VS. CIR

FACTS: Gatchalian and company, by pooling together

their resources, bought a lotto ticket. They won and are

now being charged by the CIR to pay income tax on the

prize.

HOLDING: A partnership of a civil nature was

organized because Gatchalian and company put up

money to buy a lotto ticket for the sole purpose of

dividing equally the prize which they may win, as they

in fact, did. Having organized a partnership, it is the

latter which is bound to pay the income tax and not

the individual partners pro rata.

PASCUAL VS. CIR

FACTS: Pascual et al. bought two parcels of land which

it resold to a third person. They paid the corresponding

capital gains tax, but are now also being charged with

corporate income tax on the ground that they formed a

partnership.

HOLDING: There was no partnership. The character of

habituality peculiar to business transactions engaged

in for the purpose of gain was absent. An isolated

transaction whereby two or more persons contribute

funds to buy certain real estate for profit in the

absence of other circumstances showing a contrary

intention cannot be considered as a partnership.

OBILLOS VS. CIR

FACTS: Obillos bought a parcel of land and transferred

his rights thereto to his children. The children resold

the land. They are now being taxed for corporate

income tax on the ground that they formed an

unregistered partnership.

HOLDING: There was no partnership. The sharing of

gross returns does not of itself, establish a partnership.

There must be an unmistakable intention to form a

partnership. In this case, the division of the profits was

only incidental to the dissolution of the co-ownership.

RIVERA VS. PEOPLES BANK

FACTS: Rivera was the Stephensons housekeeper and

they executed a survivorship agreement. Upon

Stephensons death, Rivera tried to claim the amount

pursuant to the agreement, but the bank refused.

HOLDING: Rivera and Stephenson were joint owners.

As such, either of them could withdraw any part of the

whole of said account during their lifetime, and the

balance, if any, upon the death of either, belonged to

the survivor.

TUASON VS. BOLANOS

FACTS: This was an action to recover possession of a

parcel of land where the plaintiff was represented by a

corporation.

HOLDING: There is nothing in the rules which prohibit

a corporation from being represented by another

person, natural or juridical. The contention that one

corporation cannot act as managing partner for

another since the two cannot enter into a partnership

is without merit since they may nevertheless, enter

into a joint venture where the nature of the venture is

in line with the business authorized by its charter.

HEIRS OF TAN ENG KEE VS. CA

FACTS: This was a complaint filed by Tan Eng Kee (and

they later continued by his heirs upon his death)

against his brother Tan Eng Lay for accounting ,

liquidation and winding up of the alleged partnership

formed between them.

HOLDING: There was no partnership between the

brothers. There was no firm account, no firm

letterheads, no certificate of partnership, no agreement

as to profits and losses, and no time fixed for the

duration of the partnership. Most importantly, for forty

years Tan Eng Kee never demanded for an accounting.

A demand for periodic accounting is evidence of

partnership. The evidence support the establishment

only of a proprietorship.

The SC also discussed the concept of a joint venture. It

said that a particular partnership is distinguished from

a joint adventure in that the latter has no firm name

and no legal personality. Also, a joint venture is usually

limited to a single transaction, while a partnership

generally relates to a continuing business.

On the other hand, in a joint account, the participating

merchants can transact business under their own

name and can be individually liable therefore.

AURBACH VS. SANITARY WARES

FACTS: This was the case where there were essentially

two groups of shareholders in the company: one

composed of Filipinos, and the other group of foreign

investors. There was an increase in the latters shares

in the company so they wanted a proportionate

increase in their nominees to the companys Board of

Directors.

HOLDING: Although a corporation cannot enter into a

partnership, it can nevertheless engage in a joint

venture with others. In this case, taking into

consideration their intent and history, the parties

formed a joint venture and not a corporation. This

becomes relevant because it implies that the argument

of ASI (the foreign investors), having been based on the

Corporation Code, will not apply.

A joint venture has been generally understood to mean

an organization formed for some temporary purpose. It

is distinguished mainly from a partnership in that the

latter contemplates a general business with some

continuity while the former is formed for the execution

of a single transaction.

LITONJUA VS. LITONJUA

FACTS: This was a suit filed by Aurelio against his

brother Eduardo for specific performance and

accounting, contending that they had a partnership

arrangement in the Odeon Theater business. This was

premised on a letter written by Eduardo, addressed to

Aurelio.

HOLDING: Eduardo and Aurelio are not partners. The

formalities required by law were not complied with, to

wit:

o When immovable property or real rights are

contributed, or when the partnership has a

capital of at least Php3,000, a public

instrument is necessary.

o When immovable property is contributed, an

inventory, signed by the parties, must be

attached to the public instrument.

BOURNS VS. CARMAN

FACTS: This was an action to recover a sum of money,

filed against Lo-Chim-Lim and his other co-defendants

on the ground that they were joint proprietors.

HOLDING: There was a partnership of cuentas en

participacion. It was a business conducted by Lo-ChimLim exclusively, in his own name, and under his

personal management. A partnership constituted in

such a manner, the existence of which was only known

to those who had an interest in the same, there being

no mutual agreements between the partners, and

without a corporate name indicating to the public in

some way that there were other people besides the one

who ostensibly managed and conducted the business,

is exactly the accidental partnership of cuentas en

participacion. Those who contract with the person

under whose name the business of such partnership is

conducted, shall have a right of action only as against

that person, and not against other persons interested,

and the latter shall likewise, have no right of action

against such third persons.

SEVILLA VS. CA

FACTS: This was the case where Sevilla had bound

herself with the corporation to pay for rent. She

managed the business but was subsequently prevented

from continuing as manager of the branch where she

worked.

HODLING: There was no partnership or joint venture

as there was no parity of standing between Sevilla and

Tourist World Services, and they did not exercise equal

rights. The court concluded that there was an agency

relationship.

PHILEX MINING VS. CIR

FACTS: Baguio Gold and Philex Mining entered into a

contract whereby the latter would operate the formers

mining claim. Philex, apart from transferring its own

funds for the business, also shelled out money to cover

for the losses incurred by the business. Philex then

attempted to deduct what it purported to be bad loans

payable to it from Baguio Gold. The CIR disallowed the

deduction.

HOLDING: The agreement between the parties created

a partnership relationship between them. As such, the

money contributed was not a loan and cannot be

deducted from the partnerships taxable income. The

strongest indication of the existence of the partnership

relation was the fact that each of them would receive

50% of the profits. By pegging its compensation as

profits, Philex stood not to be remunerated in case the

mine had no income. This is definitely not the nature of

a loan, instead, it partakes of the nature of a capital

contribution.

II. KINDS OF PARTNERSHIP

A. Universal

Art. 1776. As to its object, a partnership is either

universal or particular. As regards the liability of the

partners, a partnership may be general or limited.

Art. 1777. A universal partnership may refer to all the

present property or to all the profits.

i.

Universal Partnership of Present Property

Art. 1778. A partnership of all present property is that

in which the partners contribute all the property which

actually belongs to them to a common fund, with the

intention of dividing the same among themselves, as

well as all the profits which they may acquire

therewith.

Art. 1779. In a universal partnership of all present

property, the property which belongs to each of the

partners at the time of the constitution of the

partnership, becomes the common property of all the

partners, as well as all the profits which they may

acquire therewith.

A stipulation for the common enjoyment of any other

profits may also be made; but the property which the

partners may acquire subsequently by inheritance,

legacy, or donation cannot be included in such

stipulation, except the fruits thereof.

The prohibition in Art. 1779, 2 nd par. is in

consonance with the general provision of the Code

disallowing contracts upon future inheritance.

But it is believed that the usufruct of property

acquired by inheritance, legacy, or donation may be

stipulated as contributed to the common fund.

ii.

Universal Partnership of Profits

Art. 1780. A universal partnership of profits comprises

all that the partners may acquire by their industry or

work during the existence of the partnership.

Movable or immovable property which each of the

partners may possess at the time of the celebration of

the contract shall continue to pertain exclusively to

each, only the usufruct passing to the partnership.

In other words, all that the partners may

acquire, jointly or separately, through physical or

intellectual effort whether it be in the pursuit of a

trade or the exercise of an art or profession or

otherwise pertain to the partnership and are

subject to division among the partners upon its

termination.

It does not cover: (1) acquisitions of the

partners through any means not requiring the

exertion of human effort or intelligence; (2)

property which each of the partners acquired or

possessed before the celebration of the contract

(only the usufruct of the property passes).

Art. 1783. A particular partnership has for its object

determinate things, their use or fruits, or specific

undertaking, or the exercise of a profession or vocation.

C.

General (check Art. 1776)

A general partnership is one where all the

partners are liable subsidiarily and pro rata with

their

individual

property

for

partnership

obligations.

D.

Limited (check Art. 1776)

In a limited partnership, only some partners

are personally liable for partnership obligations;

the others are not so liable, their liability being

limited to their capital contribution.

iii. Other Rules

Art. 1781. Articles of universal partnership, entered

into without specification of its nature, only constitute

a universal partnership of profits.

Art. 1782. Persons who are prohibited from giving

each other any donation or advantage cannot enter into

universal partnership.

Art. 739. The following donations shall be void:

(1) Those made between persons who were guilty of

adultery or concubinage at the time of the donation;

(2) Those made between persons found guilty of the

same criminal offense, in consideration thereof;

(3) Those made to a public officer or his wife,

descedants and ascendants, by reason of his office.

In the case referred to in No. 1, the action for

declaration of nullity may be brought by the spouse of

the donor or donee; and the guilt of the donor and

donee may be proved by preponderance of evidence in

the same action.

B.

The presumption in Art. 1781 is in accordance

with the rule in interpretation of contracts that, in

case of doubt, that which involves the least

transmission of rights and interests will be favored.

The prohibition in Art. 1782 is founded on the

theory that a contract of universal partnership is

for all purposes a donation and, thus, seeks to

prevent

persons

disqualified

from

making

donations from doing indirectly what the law

prohibits them from doing directly.

Particular

Art. 1776. As to its object, a partnership is either

universal or particular. As regards the liability of the

partners, a partnership may be general or limited.

E.

At Will

Art. 1785. When a partnership for a fixed term or

particular undertaking is continued after the

termination of such term or particular undertaking

without any express agreement, the rights and duties

of the partners remain the same as they were at such

termination, so far as is consistent with a partnership

at will.

A continuation of the business by the partners or such

of them as habitually acted therein during the term,

without any settlement or liquidation of the

partnership affairs, is prima facie evidence of a

continuation of the partnership.

A partnership which is designed to continue

for no fixed period of time and is formed to last

only during the mutual consent or pleasure of the

parties, its existence being terminable at the will of

any one or more of them.

F.

For a Term or Undertaking (check Art. 1785)

A partnership where the period of time during

which the partnership shall exist has been

specified.

Or a partnership formed to engage in a specific

undertaking without specification of the term but,

owing to the nature of its purpose, with the implied

understanding that it shall last only and until the

completion of the undertaking.

G.

Commercial

Art. 1767. By the contract of partnership two or more

persons bind themselves to contribute money, property,

or industry to a common fund, with the intention of

dividing the profits among themselves.

Two or more persons may also form a partnership for

the exercise of a profession.

H.

A commercial partnership has for its object the

realization of some mercantile of commercial act

either as a means or an end

Professional (check Art. 1767)

This is the class of partnerships formed by

professional for the exercise of the professions they

belong to.

I.

By Estoppel/Apparent

Art. 1825. When a person, by words spoken or written

or by conduct, represents himself, or consents to

another representing him to anyone, as a partner in an

existing partnership or with one or more persons not

actual partners, he is liable to any such persons to

whom such representation has been made, who has,

on the faith of such representation, given credit to the

actual or apparent partnership, and if he has made

such representation or consented to its being made in

a public manner he is liable to such person, whether

the representation has or has not been made or

communicated to such person so giving credit by or

with the knowledge of the apparent partner making the

representation or consenting to its being made:

(1) When a partnership liability results, he is liable as

though he were an actual member of the partnership;

(2) When no partnership liability results, he is liable

pro rata with the other persons, if any, so consenting to

the contract or representation as to incur liability,

otherwise separately.

When a person has been thus represented to be a

partner in an existing partnership, or with one or more

persons not actual partners, he is an agent of the

persons consenting to such representation to bind

them to the same extent and in the same manner as

though he were a partner in fact, with respect to

persons who rely upon the representation. When all

the members of the existing partnership consent to the

representation, a partnership act or obligation results;

but in all other cases it is the joint act or obligation of

the person acting and the persons consenting to the

representation.

Partner by Estoppel:

Person who:

By (a) words spoken or written or by

conduct

Represents himself or consents

representation

As a partner in

existing partnership or

As a partner in

apparent partnership

To anyone

(b)

to

an

an

And such person has given credit to

the representation

Manner of Representation

Public

Personal/Non-public

Liability

Partnership Liability (if

there is an existing partnership and

when the act is ratified by the

partnership)

Joint Liability (if there is

only an apparent partnership)

Partnership/Joint Obligor

Requires consent

If all partners consent,

partnership act results

If only some consent, joint

act

results

among

those

who

consented and the partner by estoppel

Apparent partner becomes agent

Ortega vs. CA

The birth and life of a partnership at will is

predicated on the mutual desire and consent of the

partners.

Through the doctrine of delectus personae, all

the partners have the power, though not

necessarily the right, to dissolve the partnership.

Thus, any of the partners may dissolve the

partnership at will at his sole pleasure; but he

must do so in good faith or he will be liable for

damages.

III. KINDS OF PARTNERS

A.

Industrial

Art. 1789. An industrial partner cannot engage in

business for himself, unless the partnership expressly

permits him to do so; and if he should do so, the

capitalist partners may either exclude him from the

firm or avail themselves of the benefits which he may

have obtained in violation of this provision, with a right

to damages in either case.

Art. 1797. The losses and profits shall be distributed

in conformity with the agreement. If only the share of

each partner in the profits has been agreed upon, the

share of each in the losses shall be in the same

proportion.

In the absence of stipulation, the share of each partner

in the profits and losses shall be in proportion to what

he may have contributed, but the industrial partner

shall not be liable for the losses. As for the profits, the

industrial partner shall receive such share as may be

just and equitable under the circumstances. If besides

his services he has contributed capital, he shall also

receive a share in the profits in proportion to his

capital.

B.

The industrial partners contribution is

based on quantum meruit.

Capitalist

Art. 1789. An industrial partner cannot engage in

business for himself, unless the partnership expressly

permits him to do so; and if he should do so, the

capitalist partners may either exclude him from the

firm or avail themselves of the benefits which he may

have obtained in violation of this provision, with a right

to damages in either case.

Art. 1790. Unless there is a stipulation to the

contrary, the partners shall contribute equal shares to

the capital of the partnership.

Art. 1797. The losses and profits shall be distributed

in conformity with the agreement. If only the share of

each partner in the profits has been agreed upon, the

share of each in the losses shall be in the same

proportion.

In the absence of stipulation, the share of each partner

in the profits and losses shall be in proportion to what

he may have contributed, but the industrial partner

shall not be liable for the losses. As for the profits, the

industrial partner shall receive such share as may be

just and equitable under the circumstances. If besides

his services he has contributed capital, he shall also

receive a share in the profits in proportion to his

capital.

Art. 1808. The capitalist partners cannot engage for

their own account in any operation which is of the kind

of business in which the partnership is engaged,

unless there is a stipulation to the contrary.

Any capitalist partner violating this prohibition shall

bring to the common funds any profits accruing to him

from his transactions, and shall personally bear all the

losses.

C.

Art. 1790 embodies the presumption of

the law as to the equality in standing of the

partners.

Art. 1808 is limited to business which

competes with the partnership business; thus, it

must be the same products (same category), same

services, and in the same location.

Managing

Art. 1792. If a partner authorized to manage collects a

demandable sum which was owed to him in his own

name, from a person who owed the partnership

another sum also demandable, the sum thus collected

shall be applied to the two credits in proportion to their

amounts, even though he may have given a receipt for

his own credit only; but should he have given it for the

account of the partnership credit, the amount shall be

fully applied to the latter.

The provisions of this article are understood to be

without prejudice to the right granted to the other

debtor by Article 1252, but only if the personal credit

of the partner should be more onerous to him.

Art. 1800. The partner who has been appointed

manager in the articles of partnership may execute all

acts of administration despite the opposition of his

partners, unless he should act in bad faith; and his

power is irrevocable without just or lawful cause. The

vote of the partners representing the controlling

interest shall be necessary for such revocation of

power.

A power granted after the partnership has been

constituted may be revoked at any time.

Art. 1801. If two or more partners have been intrusted

with the management of the partnership without

specification of their respective duties, or without a

stipulation that one of them shall not act without the

consent of all the others, each one may separately

execute all acts of administration, but if any of them

should oppose the acts of the others, the decision of

the majority shall prevail. In case of a tie, the matter

shall be decided by the partners owning the controlling

interest.

Art. 1802. In case it should have been stipulated that

none of the managing partners shall act without the

consent of the others, the concurrence of all shall be

necessary for the validity of the acts, and the absence

or disability of any one of them cannot be alleged,

unless there is imminent danger of grave or irreparable

injury to the partnership.

Art. 1800 speaks of the managing

partner.

Art. 1801 refers to a situation where

there is more than one managing partner and

there is solidary management among them.

Art. 1802 speaks of joint management.

But, since this relates to the obligations of partners

inter se, the acts of a managing partner in violation

of Art. 1802 may still be binding insofar as third

persons in good faith are concerned.

D.

By Estoppel

See previous discussion on kinds of

partnerships.

IV. PARTNERS OBLIGATIONS TO THE

PARTNERSHIP

A.

To Contribute; Warrant

Art. 1786. Every partner is a debtor of the partnership

for whatever he may have promised to contribute

thereto.

He shall also be bound for warranty in case of eviction

with regard to specific and determinate things which

he may have contributed to the partnership, in the

same cases and in the same manner as the vendor is

bound with respect to the vendee. He shall also be

liable for the fruits thereof from the time they should

have been delivered, without the need of any demand.

Art. 1787. When the capital or a part thereof which a

partner is bound to contribute consists of goods, their

appraisal must be made in the manner prescribed in

the contract of partnership, and in the absence of

stipulation, it shall be made by experts chosen by the

partners, and according to current prices, the

subsequent changes thereof being for account of the

partnership.

Art. 1795. The risk of specific and determinate things,

which are not fungible, contributed to the partnership

so that only their use and fruits may be for the

common benefit, shall be borne by the partner who

owns them.

If the things contribute are fungible, or cannot be kept

without deteriorating, or if they were contributed to be

sold, the risk shall be borne by the partnership. In the

absence of stipulation, the risk of the things brought

and appraised in the inventory, shall also be borne by

the partnership, and in such case the claim shall be

limited to the value at which they were appraised.

Art. 1788. A partner who has undertaken to

contribute a sum of money and fails to do so becomes

a debtor for the interest and damages from the time he

should have complied with his obligation.

The same rule applies to any amount he may have

taken from the partnership coffers, and his liability

shall begin from the time he converted the amount to

his own use.

Art. 1789. An industrial partner cannot engage in

business for himself, unless the partnership expressly

permits him to do so; and if he should do so, the

capitalist partners may either exclude him from the

firm or avail themselves of the benefits which he may

have obtained in violation of this provision, with a right

to damages in either case.

Art. 1790. Unless there is a stipulation to the

contrary, the partners shall contribute equal shares to

the capital of the partnership.

Art. 1791. If there is no agreement to the contrary, in

case of an imminent loss of the business of the

partnership, any partner who refuses to contribute an

additional share to the capital, except an industrial

partner, to save the venture, shall he obliged to sell his

interest to the other partners.

The 2nd sentence of Art. 1786, when it

speaks of specific and determinate things, refers to

non-fungible things.

Art. 1786 only specifically talks about

warranty against eviction but Prof. Bautista states

that the other warranties of sale (warranty against

hidden defects and warranty for merchantability

for purpose) should also be made applicable.

Art. 1786 explicitly does away with the

need for demand as to the fruits in the last

sentence thereof.

The appraisal in Art. 1787 is

necessary to know the value of the capital

contribution of property.

o

Valuation

is

usually

done

by

agreement because the transfer of property to

the partnership is similar to a sale; or it may

be done by an expert (appraiser).

o

If its through the former, the value is

based on the agreement. But if its throught he

latter, the value is based on current prices or

the fair market value

Art. 1791 refers to total loss of the

business such that the partnership can no longer

continue to pursue its purpose.

o

There must first be capital call; there

must be an agreement for everyone to

contribute to continue the business; after such

agreement, the failure to contribute gives the

right to buy-out the interest of the

uncontributing partner.

Under the 1st par. of Art. 1795, the

partner retains ownership because he only

contributes the usufruct and, thus, he still bears

the risk of loss (principle of respirit domino); it also

only refers to non-fungible things.

Under the 2nd par. of Art. 1795, if a

partner loses the fungible goods before delivery, he

remains an obligor and, thus, still a partner

subject to the delivery of his contribution, which is

a fungible thing.

Note that the

transferable by stipulation.

risk

of

loss

is

To Apply Sums Collected Pro Rata

B.

Art. 1792. If a partner authorized to manage collects a

demandable sum which was owed to him in his own

name, from a person who owed the partnership

another sum also demandable, the sum thus collected

shall be applied to the two credits in proportion to their

amounts, even though he may have given a receipt for

his own credit only; but should he have given it for the

account of the partnership credit, the amount shall be

fully applied to the latter.

The provisions of this article are understood to be

without prejudice to the right granted to the other

debtor by Article 1252, but only if the personal credit

of the partner should be more onerous to him.

To Compensate

C.

Art. 1794. Every partner is responsible to the

partnership for damages suffered by it through his

fault, and he cannot compensate them with the profits

and benefits which he may have earned for the

partnership by his industry. However, the courts may

equitably lessen this responsibility if through the

partner's extraordinary efforts in other activities of the

partnership, unusual profits have been realized.

This also covers negligence of a partner

To Be Loyal; Fiduciary Duty

D.

Art. 1807. Every partner must account to the

partnership for any benefit, and hold as trustee for it

any profits derived by him without the consent of the

other partners from any transaction connected with

the formation, conduct, or liquidation of the

partnership or from any use by him of its property.

o

o

Basic fiduciary duties of a partner:

Account for any profit acquired in a

manner injurious to the partnerships interest;

Cannot

acquire

for

himself

a

partnership asset nor divert to his own use a

partnership opportunity;

Must not compete with partnership

within its scope of business.

Liwanag vs. CA

Even when a contract of partnership has been entered

into, when money or property have been received by a

partner for a specific purpose and he later

misappropriated it, such partner is guilty of estafa.

US vs. Clarin

When a partner contributes to the common fund,

he invests it in the risks or benefits of the business

and, even if only the usufruct over the money has

been conveyed, the duty to return such capital

devolves upon the partnership and not any of the

partners.

When money has been received by the partnership,

the business commenced and profits accrued, the

action that lies with the partner who furnished

capital for recovery of his money is not a criminal

action for estafa, but a civil one arising from the

partnership contract for a liquidation of the

partnership and a levy on its assets if there should

be any.

Pang Lim vs. Lo Seng

Partners

are

required to

exhibit towards each other the highest degree of

good faith because the relation is essentially

fiduciary as each is considered the confidential

agent of the other.

Therefore, one partner cannot,

to the detriment of another, apply exclusively to his

own benefit the results of the knowledge and

information gained in the character of partner.

Catalan vs. Gatchalian

The

right

of

redemption

pertains to the owner of the property; as it was the

partnership which owned the property, in this

case, it was only the partnership which could

properly exercise the right of redemption.

When Catalan redeemed the

properties, he became a trustee and held the same

in trust for his co-partner Gathchalian, subject to

his right to demand from the latter his

contribution to the amount of redemption.

V. PARTNERS OBLIGATION INTER SE

A. To bring to collation

Art. 1793. A partner who has received, in whole or in

part, his share of a partnership credit, when the other

partners have not collected theirs, shall be obliged, if

the debtor should thereafter become insolvent, to bring

to the partnership capital what he received even

though he may have given receipt for his share only.

(1685a)

There is one debtor and one or 2 partners have

received their share of debt in their personal

capacity then the debtor becomes insolvent

Pioneer Insurance v. CA

Quick Facts: Lim, owner-operator of Southern Air

Lines, purchased 2 aircrafts and set of spare parts

form Japan Domestic Airlines to be paid in

installments. Pioneer executed a surety bond in favor of

JDA for the balance. Bormaheco, Cervanteses and

Maglana contributed funds for the formation of a new

corporation proposed by Lim. There was no

incorporation.

Ratio: Persons who attempt, but fail, to form a

corporation and who carry on business under the

corporate name occupy the position of partners inter

se. However, such a relation does not necessarily exist,

for ordinarily persons cannot be made to assume the

relation of partners, as between themselves, when their

purpose is that no partnership shall exist and it should

be implied only when necessary to do justice between

the parties. Lim never intended to form a corporation

despite his representations. No de facto partnership

was created.

Evangelista & Co. v. Abad Santos

Quick Facts: Judge Abad Santos is an industrial

partner in Evangelista & Co. with 3 petitioners who

were the capitalist partners. Abad Santos alleged that

the other 3 partners were refusing to let her examine

the partnership books and were not paying her share

in the profits. Other 3 are arguing that Abad Santos

could not be an industrial partner since she was a City

Court judge (Art.1789).

Ratio: Abad Santos is not engaged in any business

antagonistic to the partnership as being a judge can

hardly be characterized as a business.

B. To share in the profits/losses

Art. 1797. The losses and profits shall be distributed

in conformity with the agreement. If only the share of

each partner in the profits has been agreed upon, the

share of each in the losses shall be in the same

proportion.

In the absence of stipulation, the share of each partner

in the profits and losses shall be in proportion to what

he may have contributed, but the industrial partner

shall not be liable for the losses. As for the profits, the

industrial partner shall receive such share as may be

just and equitable under the circumstances. If besides

his services he has contributed capital, he shall also

receive a share in the profits in proportion to his

capital. (1689a)

Liability for loss refers to loss AFTER liquidation

In case of losses, it can be stipulated that the

industrial partner share in the losses

Art. 1798. If the partners have agreed to intrust to a

third person the designation of the share of each one in

the profits and losses, such designation may be

impugned only when it is manifestly inequitable. In no

case may a partner who has begun to execute the

decision of the third person, or who has not impugned

the same within a period of three months from the

time he had knowledge thereof, complain of such

decision.

The designation of losses and profits cannot be

intrusted to one of the partners. (1690)

The designation of profits and losses may be

designated to 2 or more partners, but not to 1

partner

Art. 1799. A stipulation which excludes one or more

partners from any share in the profits or losses is void.

(1691)

Moran, Jr. v. CA

Quick Facts: Pecson and Moran entered into an

agreement to print 95,000 posters (featuring the

delegates of the 1971 Con-Con). They agreed each

would contribute P15,000 and that Pecson would

receive P1,000 commission per month. Pecson

contributed P10,00; Moran supervised the work. Only

2,000 posters were printed. Pecson filed an action

asking for the return of his contribution, profits he

would have earned and promised commission.

Ratio: There is no basis for the award of speculative

damages in favor of Moran as there was no evidence

that the partnership would be a profitable venture.

Partners are to share in the profits and the losses.

However, Pecson is not barred from totally recovering.

He is entitled to P6,000 (out of P10,000 only P4,000

was used in printing) for his contribution which

remained unused and P3,000 for share in net profits

from the sale of 2,000 posters.

(Sir noted that there was an award of unused capital

even if there was no liquidation.)

C. To render true and full information

Art. 1806. Partners shall render on demand true and

full information of all things affecting the partnership

to any partner or the legal representative of any

deceased partner or of any partner under legal

disability. (n)

Martinez v. Ong Pong Co

Quick Facts: Martinez delivered P1,500 to Ong Pong Co

and Ong Lay to invest in a store. They agreed that the

profits and losses would be equally shared by all of

them. Martinez was demanding for the 2 Ongs to

render an accounting or to refund him the P1,500. Ong

Pong Co alleged that Ong Lay, now deceased was the

one who managed the business, and the capita of

P1,500 resulted in a loss.

Ratio: The 2 partners (Ongs) were the administrators

and obliged to render accounting. Since neither of

them rendered an account nor proven the losses, they

are obliged to return the capital. Art. 1796 is not

applicable because no other money than that

contributed as capital was involved. The liability of the

partners is joint. Ong Pong Co shall only pay P750 to

Martinez.

Agustin v. Inocencio

Quick Facts: The parties are all industrial partners.

For the construction of a casco, profits of the business

were contributed and money was borrowed from wife of

the managing partner, Inocencio, Inocencio also

advanced funds necessary to complete the work. The

other partners were not informed of the borrowing and

the advancement but the books were always open to

their inspection.

Ratio: The nature of the transaction (construction of

casco) was within the scope of the business of the

partnership so Inocencio, in borrowing money and

advancing funds, was acting within the scope of his

authority as a managing partner. All the partners are

liable for the debt.

Soncuya v. De Luna

Quick Facts: Soncuya, de Luna and deceased Avelino

were members of a partnership, Centro Escolar de

Senoritas. Soncuya filed a complaint praying for

damages as result of the fraudulent administration by

managing partner De Luna.

Ratio: For a partner to be able to claim damages

allegedly suffered by him by reason of the fraudulent

administration of the managing partner, a previous

liquidation of the partnership is necessary. A

liquidation of the business is necessary so the

following may be determined: profits and losses, causes

of the losses, responsibility of the defendant and

damages each partner may have suffered.

D. Not to engage in another business

Art. 1789. An industrial partner cannot engage in

business for himself, unless the partnership expressly

permits him to do so; and if he should do so, the

capitalist partners may either exclude him from the

firm or avail themselves of the benefits which he may

have obtained in violation of this provision, with a right

to damages in either case. (n)

Art. 1808. The capitalist partners cannot engage for

their own account in any operation which is of the kind

of business in which the partnership is engaged,

unless there is a stipulation to the contrary.

VI.

PARTNERS OBLIGATIONS TO

PERSONAL AND PARTNERSHIP

CREDITORS; THIRD PARTIES

A. To have his partnership interest charged for

personal debts (primary)

Art. 1814. Without prejudice to the preferred rights of

partnership creditors under Article 1827, on due

application to a competent court by any judgment

creditor of a partner, the court which entered the

judgment, or any other court, may charge the interest

of the debtor partner with payment of the unsatisfied

amount of such judgment debt with interest thereon;

and may then or later appoint a receiver of his share of

the profits, and of any other money due or to fall due to

him in respect of the partnership, and make all other

orders, directions, accounts and inquiries which the

debtor partner might have made, or which the

circumstances of the case may require.

The interest charged may be redeemed at any time

before foreclosure, or in case of a sale being directed by

the court, may be purchased without thereby causing a

dissolution:

(1) With separate property, by any one or more of the

partners; or

(2) With partnership property, by any one or more of

the partners with the consent of all the partners whose

interests are not so charged or sold.

Nothing in this Title shall be held to deprive a partner

of his right, if any, under the exemption laws, as

regards his interest in the partnership. (n)

remedy of a judgment creditor against a partner

This refers to partners interest in the partnership

and NOT to his right over a specific partnership

property

partners interest share of the profits and

surplus

rights to specific partnership property right

of possession for partnership purposes

CHARGING ORDER

- attaches interest of the partner

1) Directs the partnership to pay any profits that

may be due to the judgment debtor, in favour of the

judgment creditor in satisfaction of his credit

(including interests)

2) May ask the court to appoint a receiver

- to collect money

3) may be sold at auction/foreclosure

remedy: right of redemption

a) with separate property

b) with partnership property

(requires the consent of all partners)

Best Choice?

No. 1 first since the payment will be ongoing

No. 2 comes second

No. 3 is a poor remedy, single payment; net effect: only

sell back to judgment debtor

Art. 1827. The creditors of the partnership shall be

preferred to those of each partner as regards the

partnership property. Without prejudice to this right,

the private creditors of each partner may ask the

attachment and public sale of the share of the latter in

the partnership assets. (n)

Art. 1817. Any stipulation against the liability laid

down in the preceding article shall be void, except as

among the partners. (n)

VOID as against 3rd parties

therefore, as to them, pro rata liability applies

except as among partners

if there is waiver by some parties, those

benefitted can claim against the other partners

what he paid pro rata

preference of partnership creditors over personal

creditors (in case of insolvency or liquidation)

2nd sentence: without prejudice to private creditors

right to ask attachment

B. To be liable pro rata for partnership debts

(subsidiary & joint)

Art. 1816. All partners, including industrial ones,

shall be liable pro rata with all their property and after

all the partnership assets have been exhausted, for the

contracts which may be entered into in the name and

for the account of the partnership, under its signature

and by a person authorized to act for the partnership.

However, any partner may enter into a separate

obligation to perform a partnership contract. (n)

refers to all GENERAL partners

- can industrial partners be general partners? YES

- as a GR, all partners are general partners

exception: stipulation limited partner

liable pro rata with all their property

both real and personal

Art. 1835. The dissolution of the partnership does not

of itself discharge the existing liability of any partner.

A partner is discharged from any existing liability upon

dissolution of the partnership by an agreement to that

effect between himself, the partnership creditor and

the person or partnership continuing the business;

and such agreement may be inferred from the course of

dealing between the creditor having knowledge of the

dissolution and the person or partnership continuing

the business.

The individual property of a deceased partner shall be

liable for all obligations of the partnership incurred

while he was a partner, but subject to the prior

payment of his separate debts. (n)

- why not solidary liability?

separate juridical personality of the partnership;

therefore, exhaust partnership assets first

partnership obligation

1) entered in the firm name, under its signature

2) by a person authorized (ex: employee)

2nd paragraph

discharged

1) agreement

- (3 parties: partner, creditor, and partnership)

2) no agreement

- knowledge of the creditor and continues to

transact with the partnership continuing the

business

subsidiarily and pro rata for all partnership

obligations

pro rata

= proportional

- basis? in proportion to his SHARE in the PROFITS

NOT capital contribution

what if other parties waived?

3rd paragraph

estate

pay personal debts before partnership debts

condition:

a) dead partner

b) no more partnership assets

when SOLIDARILY liable? last sentence

C. Tort liability; breach of trust liability (primary

& solidary)

separate obligation to perform a partnership

contract

1) agrees to solidary liability (this provision)

2) 1822 (tort liability)

3) 1823 (misappropriation)

Art. 1822. Where, by any wrongful act or omission of

any partner acting in the ordinary course of the

business of the partnership or with the authority of copartners, loss or injury is caused to any person, not

being a partner in the partnership, or any penalty is

incurred, the partnership is liable therefor to the same

extent as the partner so acting or omitting to act. (n)

TORT (wrongful act or omission)

a) ordinary course of the business

b) not in pursuance BUT with the authority of the

co-partners

c) penalty refers to a crime

Art. 1823. The partnership is bound to make good the

loss:

(1) Where one partner acting within the scope of his

apparent authority receives money or property of a

third person and misapplies it; and

(2) Where the partnership in the course of its business

receives money or property of a third person and the

money or property so received is misapplied by any

partner while it is in the custody of the partnership. (n)

MISAPPROPRIATION

Art. 1824. All partners are liable solidarily with the

partnership for everything chargeable to the

partnership under Articles 1822 and 1823. (n)

SOLIDARY LIABILITY

D. Liability in case of estoppels

Art. 1825. When a person, by words spoken or written

or by conduct, represents himself, or consents to

another representing him to anyone, as a partner in an

existing partnership or with one or more persons not

actual partners, he is liable to any such persons to

whom such representation has been made, who has,

on the faith of such representation, given credit to the

actual or apparent partnership, and if he has made

such representation or consented to its being made in

a public manner he is liable to such person, whether

the representation has or has not been made or

communicated to such person so giving credit by or

with the knowledge of the apparent partner making the

representation or consenting to its being made:

(1) When a partnership liability results, he is liable as

though he were an actual member of the partnership;

(2) When no partnership liability results, he is liable

pro rata with the other persons, if any, so consenting to

the contract or representation as to incur liability,

otherwise separately.

When a person has been thus represented to be a

partner in an existing partnership, or with one or more

persons not actual partners, he is an agent of the

persons consenting to such representation to bind

them to the same extent and in the same manner as

though he were a partner in fact, with respect to

persons who rely upon the representation. When all

the members of the existing partnership consent to the

representation, a partnership act or obligation results;

but in all other cases it is the joint act or obligation of

the person acting and the persons consenting to the

representation. (n)

PARTNERSHIP BY ESTOPPEL

liability

- liable as a partner: pro rata and subsidiary

ONLY WHEN it results in a partnership liability

There is partnership liability when all the partners

consent to the representation

allows to be represented as a partner to a nonpartner

liability joint, as if one of those liable

Corporation Code

Sec. 21. Corporation by estoppel. - All persons who

assume to act as a corporation knowing it to be

without authority to do so shall be liable as general

partners for all debts, liabilities and damages incurred

or arising as a result thereof: Provided, however, That

when any such ostensible corporation is sued on any

transaction entered by it as a corporation or on any

tort committed by it as such, it shall not be allowed to

use as a defense its lack of corporate personality.

One who assumes an obligation to an ostensible

corporation as such, cannot resist performance thereof

on the ground that there was in fact no corporation.

assume to act as a corporation

- corporations MUST be registered with the SEC

knowing to be without authority bad faith

liable as general partners pro rata and

subsidiarily

in effect: partnership by estoppels

ostensible corporation

lack of corporate personality cannot be used as a

defense

2nd paragraph

-contemplates a situation where 3rd party is being

sued

-third person assumes liability, also cannot make

use of the lack of personality

E. Liability of new partners (subsidiary)

Art. 1826. A person admitted as a partner into an

existing partnership is liable for all the obligations of

the partnership arising before his admission as though

he had been a partner when such obligations were

incurred, except that this liability shall be satisfied

only out of partnership property, unless there is a

stipulation to the contrary. (n)

new partnership

- old partnership ipso jure dissolved BUT:

- same assets and same firm name

- therefore, same liability

new partners liability extent: limited to his capital

contribution

In re Sycip

GR if partner dies: Partnership is DISSOLVED.

- in case of firm names, Art. 1815 prefers to living

persons

- public relations use of deceased partners name

SC: undue advantage

- Art. 1840 no saleable goodwill to be distributed as a

firm asset on its dissolution

- on customs: judicial custom v. social custom

judicial custom can supplement statutory law

- result: firms DID NOT comply! SC merely denied and

ADVISED

Litton v. Hill

- Hill: Ceron entered into in his own name. I told

Litton, well be dissolved!

- SC: joint management

It is enough for the third party to transact with the

managing partner

- what if third party is required to determine?

result: hinder commercial transactions

- presumption of mutual agency

MacDonald v. National City Bank

representation

- defectively formed corporation/partnership

de facto partnership

- for purposes of the Chattel Mortgage Law, a de facto

partnership also has domicile

Compania Maritima v. Muoz

- TC absolved industrial partner on the theory that

nothing was contributed

- SC: contributed industry, general partner

- unfair? NO, had a voice in management and shared

in the profits

Co-Pitco v. Yulo

The fact that the other partner had left the country

CANNOT increase the liability of remaining partners.

extends to insolvent and dead partners

Pacific Commercial v. Aboitiz

*applied Compania doctrine

- distinguished loss from liability

- while A141 of the Code of Commerce provides that

industrial partners will not be liable for loss, A127

(which applies in this case) provides that ALL partners

are liable for for transactions in the name of the

partnership, albeit subsidiarily

Magdusa v. Albaran (in the quiz)

- demanded shares upon withdrawal from the

partnership, suit against capitalist, managing partner

only

- SC: partners share cannot be returned without first

dissolving and liquidating because of the preference for

partnership creditors AND the fact that the others

partners are indispensible parties to the suit

- since the liquidation document prepared by the

managing partner was not signed by the others, it does

not bind them

- moreover, the managing partner could not be held

personally liable since as such MP, he merely acts as a

trustee of the partnership

Island Sales v. United

- the case was dismissed, upon motion of the plaintiff,

in favour of one of the 5 general partners

- SC: clarified pro rata liability remained at 1/5;

condonation of one did not unmake him as a general

partner to effect an increase in the shares of the other

partners

Munasque v. CA

- misunderstanding between the partners

- SC: third party had the right to presume the

authority of the partner when the contract was entered

into in the name of the partnership authority

- since the payments were misappropriated, Art. 1823

would apply on solidarity of liability

Lim Tong Lim v. Philippine Fishing Gear, Inc.

- fact of partnership: common funds, purpose of

business, sold boat for partners debt, sharing of

profits

- SC: corporation by estoppels applies against third

persons who benefitted (partner); therefore, liable as a

general partner despite not being named in the

contract

Bachrach v. La Protectora