Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Simon Goldhill, WHAT IS EKPHRASIS FOR?

Încărcat de

Jesus MccoyDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Simon Goldhill, WHAT IS EKPHRASIS FOR?

Încărcat de

Jesus MccoyDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

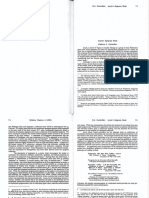

What Is Ekphrasis For?

Author(s): Simon Goldhill

Source: Classical Philology, Vol. 102, No. 1, Special Issues on Ekphrasis<break></break>Edited

by Shadi Bartsch and Ja Elsner (January 2007), pp. 1-19

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/521129 .

Accessed: 14/03/2014 04:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Classical Philology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WHAT IS EKPHRASIS FOR?

simon goldhill

his article broaches a simple question. What is an ekphrasis for?

A considerable amount has been written about what particular ekphraseis might mean. In the last twenty years especially, classicists

have spent a great deal of protable time both outlining the formal elements

by which an ekphrasis can be recognized, and producing innumerable narratological analyses of how ekphraseis and surrounding narratives interrelate,

from the most formal types of cataloguing to elaborate tracing of detailed

signicances. 1 These days, a reading of Vergils Aeneas standing before the

temple doors of Carthage that didnt talk about focalization, framing, and

proleptic signication wouldnt get off the grid. 2 There is a booming literature on ekphrasis outside classics, too, though it rarely knows the classical

material adequately. 3 Things do look very different from twenty years ago

and all for the better. But when I turn, as I will in the second half of this paper,

to an anthology of thirty-six poems written by different poets about the same

sculpture of a cow, the question What is an ekphrasis for? becomes more

insistentand quite a bit harder to answer. Why should anyone want to write

or read or collect such poems? How many of Philostratus Imagines do you

need to readand why? What do such collections do ? If we nd such

anthologies boring or trivialand the lack of detailed discussion of both

Philostratus and the poems on Myrons Cow suggest that critics have not been

enthused by these works 4we should investigate what the cultural difference

between ancient and modern concerns can tell us.

I have elsewhere tried to answer some of these questions with a study of

the Hellenistic invention of the ekphrastic epigram. 5 From the third century

b.c.e. onwards for the next four hundred years and more, the epigram is one

1. A selection of studies of classical works might include Becker 1990, 1995; Barchiesi 1997b; Stanley

1993; Elsner 1991; Hardie 2002b; Laird 1996; Zeitlin 1989, 1994; and Goff 1988. For the most recent collection, see Elsner 2002b. All have further bibliographies.

2. I am referring to the standard and much-cited article of Fowler (1991).

3. See, e.g., Krieger 1992; Heffernan 1993; Mitchell 1994; Boehm and Pfotenhauer 1995; Hollander

1988, 1995; Scott 1994; P. Wagner 1996. For a bibliography of earlier works, see Goldhill and Osborne

1994, p. 305, n. 4.

4. But on Philostratus, do see Blanchard 1986; Bryson 1994; Elsner 2000; and the forthcoming volume

edited by Bowie and Elsner; and on Myrons Cow, see Gutzwiller 1998, 24550 (with further bibliography,

p. 245, n. 39).

5. Goldhill 1994. For a willful and ill-informed misreading of this piece, see Zanker 2004, 8284; it is

a pity that he thinks I use the word discourse to mean conversation.

Classical Philology 102 (2007): 119

[ 2007 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved] 0009-837X/07/10201-0001$10.00

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Simon Goldhill

of the prime exemplars of ekphrastic writing. It takes its cue from epigrams

inscribed on graves and other monuments, which describe the monument or

the graves contents. But the epigrams become increasingly baroque, ctionalized, and sophisticated. In that earlier article, I looked in particular at poems

that try to decipher graves that have riddling, rebuslike signs on them, as

well as at poems offering particular analyses of famous artworks, and longer

poems showing women in front of art reading the images for usa parody

of the artistic discourse of the period. Certain key issues emerge from this

incredibly rich archive of material. First, what is dramatized in each of these

poems is the moment of looking as a practice of interpreting, of reading

a way of seeing meaning. There is some description, especially where the

artwork is unlikely to be known, but this is always subordinate to the work

of analysis, or to the work of responding. And it is a very particular sort

of analyzing and response. In the Hellenistic period, the viewer aims for

a clever, pointed, intellectualized revelation of the sediments of meaning.

It dramatizes not just an interpretation, but a sophosan educated wit

interpreting.

This leads to the second point. Many of the poems discuss how to look as

they do it. The poems dramatize the viewing subject seeing himself seeing.

This is all too often undervalued in discussions of ekphrasis. We see the

category of professional viewer being developed, contested, and competed

for. The critical gaze, which is the sign of the art historian, nds its institutional origin here.

This critical gaze, thirdly, is committed to a value-laden view of things.

It creates and regulates the viewing subjectboth by a selection of what to

look at and how to lookand by parallel exclusions too. The epigrams endemic concern for the discrete, pointed, witty surprise is part and parcel of

what is known as Hellenistic aesthetics. You must learn to look like this.

Fourth, this critical viewing is also part of a wider theorization of the visual.

As Michael Baxandall has written, seeing is a theory-laden activity. 6 There

is a highly developed discourse of viewing in Hellenistic culture, for which

the notion of phantasiaimpressionis crucial. It offers a philosophical and

physiological explanation of how viewing functions, and is related to psychological processes and the production of speech. This demands that ekphrasis

also be related to the idea of spectacle, displaying in art galleries, museums,

rhetorical performance, and so onthe culture of viewing and the culture of

display are mutually implicative and supportivea sociological and intellectual background all too often forgotten in literary analyses of ekphrasis.

In short, ekphrasis is designed to produce a viewing subject. We read to

become lookers, and poems are written to educate and direct viewing as a

social and intellectual process. When today the modern gallery visitor looks

at a painting, and feels the need to make an intelligent, precise, witty, public

remark to a friend, this visitor ishowever belatedly or unconsciouslyan

heir of the Hellenistic sophos and his epigrams.

6. Baxandall 1985, 107.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

Within such a general framework, I want in this article to develop two

lines of argument. The rst is to look at two areas of theoretical inquiry,

which have attempted to nuance or change this general picturenamely,

the claim on the one hand that the study of rhetorical handbooks is the key

theoretical guide to understanding ekphrasis and, on the other, the claim to

have discovered in the ekphrastic tradition a female viewing subject and a

tradition of female ekphrastic poetry. I intend to explore how these claims

bear up, both in theoretical terms and in relation to the extant material we

possess. Second, I want to see how this theoretical material relates specically

to one particular set of poemsthe thirty-six epigrams on Myrons Cow.

This unique archive is interesting enough in itself: it is hard to think of any

other work of art that is treated by such a coherent and extensive body of

poetry by different hands. The issues raised by these poems, however, are,

I believe, also relevant to a discussion of ekphrasis in any period.

I

Let us start with rhetoric, and the instruction provided by the handbooks

of rhetoric for understanding ekphrasis. The handbooks in question date as

early as the rst century c.e. with Theon in Greek and Quintilian in Latin, run

through gures such as Hermogenes in the second century, Aphthonius in

the fourth, Nicolaus in the fthand, of course, Menander Rhetor, probably

at the beginning of the fourth. 7 The rhetoricians suggest that an ekphrastic

logos is one of the exercises that should be part of a program of progumnasmata, the training activity of a budding orator. Theon gives this denition:

ekfrasi ejst lovgo perihghmatiko; ejnarg up oyin agwn to; dhlouv menon

(Ekphrasis is a descriptive speech that brings the thing shown vividly before

the eyes). This denition appears throughout the tradition with almost no

change. It utilizes a key rhetorical idea that goes back to Aristotle, the notion

of enargeiathe ability to make visible. 8 This is one of the orators most

important weapons of persuasion, and ekphrasis is, as it were, the practice

of enargeia, as enargeia is one of the virtues [aretai] of ekphrasis. 9 The

aim is to make an audience almost become viewers, as Nicolaus puts it.

The qualication almost is important. Rhetorical theory knows well that

its descriptive power is a technique of illusion, semblance, of making to

appear. This brings ekphrasis particularly close to the theatrethe space

of seeing and illusion. And it is striking how often the prose of the novels in

particular reverts to theatrical scenes and metaphors at its most heightened

moments of trying to make emotional crises visible to its readers. 10

What interests me in the rhetorical handbooks is not so much the wide

range of potential subjects for ekphrasiswhich include battles and places,

7. I have learned in particular from Webbs still-unpublished book on rhetorical handbooks; see also Webb

1997a, 1999, 2000, 2001; Russell 1981; and, now, Heath 2004.

8. Aristotle himself does not use the term enargeia, which appears to have become a key technical

term in the Hellenistic period; see Zanker 1981.

9. Theon Prog. 11; Hermog. Prog. 10.

10. I have learned here in particular from the as-yet-unpublished but eagerly awaited Sather Lectures of

Froma Zeitlin (199596).

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Simon Goldhill

as well as more abstract notions like character and seasonsalthough this

does show how ekphrasis as description bleeds into all forms of writing as

well as into a more general sense of a visual regime. Rather, I am interested

in the psychological analysis of ekphrasis. Quintilian uses the notion

of phantasia, impression, 11 to insist that through enargeia in ekphrastic

prose the orator can reach the innermost mindthe deepest emotionsof

the listener (Inst. 6.2.29):

quas fantasa Graeci vocant (nos sane visiones appellemus), per quas imagines rerum

absentium ita repraesentantur animo, ut eas cernere oculis ac praesentes habere videamur,

has quisquis bene ceperit, is erit in adfectibus potentissimus. quidam dicunt eufantasitaton, qui sibi res, voces, actus secundum verum optime nget.

What the Greeks call phantasiai (let us call them visiones), it is through these that images

of absent things are represented to the mind in such a way that we seem to see them with

our eyes and to be in their presence. Whoever has mastery of them will have the most

powerful effect on the emotions. Some people say that this type of man who can imagine

in himself things, words, and deeds well and in accordance with truth is euphantasiotatos

[most skilled in summoning up phantasiai].

The orator who is euphantasiotatosskilled in the work of phantasiais

most powerful at getting into the emotionsin adfectibusof his listeners.

Vivid language penetrates the emotions. This is described in an absolutely

fascinating way by Longinus in his treatise On the Sublime (15.9):

t ou n hJ rJhtorikh; fantasa duvnatai polla; me;n sw ka alla to lovgoi ejnagnia ka

ejmpaqh proseisfevrein, katakirnamevnh mevntoi ta pragmatika ejpiceirhvsesin ou peqei

to;n akroath;n movnon, alla; ka doulou tai.

What then is the effect of rhetorical visualization? There is much it can do to bring

urgency and passion into our words; but it is when it is closely involved with factual

arguments that as well as persuading the listener, it enslaves him.

Longinus species that enargeia not only persuades but enslaves the listener.

That is its power. The danger, and I stress the word, is that the listener becomes

a slave, douloutai. This is the constant threat of rhetoricto emasculate,

defeat, humble its audience. A good listener knows to resist, to be critical.

But phantasia gets you where it is hardest to defend. It is most effective,

however, when it is linked to factual exposition. Factual exposition may

seem a surprising focus for these psychological effects, but Longinus expands

on this ability of visualization to overpower the listener in such factual cases

in quite extraordinary terms (15.1011):

ama ga;r t pragmatik ejpiceiren oJ rJhvtwr pefavntastai, dio; ka to;n tou peqein oron

uperbevbhke t lhvmmati. fuv sei dev pw ejn to toiouv toi apasin ae tou krettono akouvomen,

oqen apo; tou apodeiktikou perielkovmeqa e to; kata; fantasan ejkplhktikovn, to; pragmatiko;n ejgkruv ptetai perilampovmenon. ka tou t ouk apeikovtw pavscomen: duen ga;r

suntattomevnwn uf en, ae to; kretton e eJauto; th;n qatevrou duv namin perisp.

Here the orator uses a visualization actually in the moment of making his factual argument,

with the result that his thought has taken him beyond the limits of mere persuasiveness.

11. I have discussed phantasia (with extensive bibliography) in Goldhill 1994 and 2001a.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

Now our natural instinct is, in all such cases, to attend to the stronger inuence, so that

we are diverted from the demonstration to the astonishment caused by the visualization, which by its very brilliance conceals the factual aspect. This is a natural reaction:

when two things are joined together, the stronger attracts to itself the force of the weaker.

A brilliant visualization, then, has the power to astonishekplessein, that

key term for psychological affect in rhetorical and realist art. Visualization

amazes. In so doing, visualization conceals facts. Visualization is a blind. It

does not merely describe or make the listener think he was thereits brilliance

dazzles. And, conrms Longinus, this is a natural psychological response.

We are dragged by force away from proof, away from demonstration towards

passive experience: paschomen. Phantasia, which utilizes the same power

of enargeia as ekphrasis, does something to the listener. It is a weapon of

rhetoric.

Maybe this strong sense of the violence of enargeia will help us read a

passage of Plutarch with a more focused attention. He is commenting on the

famous bon mot of Simonides that painting is silent poetry, poetry painting

that speaks. He points out that artists and writers seek the same effects with

different materials. The one uses colors and designs, crmasi ka schvmasinalthough in the opposition he has constructed he is referring to painters,

both terms are easily and regularly used of prose too; the other uses words

and phrases, ojnovmasi ka levxesi. But despite the difference in medium, both

are engaged in edwlopoien, making of images, and their underlying aim

is the same. This leads to his discussion of historians and Thucydides in

particular (Bellone an pace clariores fuerint Athenienses 3, Mor. 347a):

ka tn storikn kravtisto oJ th;n dihvghsin w sper grafh;n pavqesi ka prospoi edwlopoihvsa. oJ goun Qoukuddh ae t lovg pro; tauv thn amillatai th;n ejnavrgeian, oon

qeath;n poihsai to;n akroath;n ka ta; ginovmena per tou; oJrnta ejkplhktika; ka taraktika; pavqh to anaginskousin ejnergavsasqai licneuovmeno.

The most powerful historian is he who, by the imaging of emotions and characters, makes

his narration like a painting. Thucydides is always striving for this quality of vividness

(enargeia) in his prosehe is desperately keen to make the listener a viewer and to

produce in those who read about events the vivid emotions of amazement and confusion

that were experienced by those who saw them.

So Thucydides the historian is a master of enargeia because he produces

in the reader the same feelings of astonishment and amazement that those

who saw the events actually felt. 12 When we read Thucydides we experience

emplektika kai taraktika pathe, emotions of amazement and confusion,

which Longinus sees as a way of getting past the censor of the intellect, a

way of dazzling us away from factual representation. If Plutarch is implying

an understanding of the psychological impact of phantasia similar to that of

Longinus, it offers a surprising and fascinating stance on Thucydides. This

is not the objective and cold Thucydides, but Thucydides the rhetorician,

12. The rhetorical treatises regularly use Thucydides description of a night battle as an example of

powerful ekphrasis. Plutarch is not alone in taking Thucydides as an exemplar.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Simon Goldhill

blinding the reader with his science, leading the reader away from analysis

into passion and confusion.

Rhetorical theory, then, suggests a stronger and more interesting sense of

what visualization is for. Phantasia relies on enargeia, as does ekphrasis.

It is a rhetorical weapon to get around the censor of the intellect, to cut the

listener off from the facts, to leave him not just as if a viewer at events,

but with the destabilizing emotions of that event. This sense of what rhetoric

makes of the power of enargeia seems to me to have been largely left out

of contemporary discussions of the ekphrastic mode. If rhetoric is to be a

guideand it seems to me it is an integral aspect of the horizon of expectation of ancient intellectualsthen the psychology of visualization and its

violent manipulation of an audience must also be considered.

When Longinus introduces the topic of phantasia, he writes, I use this

word phantasia for what some people call eidolopoiein, image production

(15.1)the very word Plutarch uses for the shared aim of poets and painters.

Longinus continues (15.1):

kaletai me;n ga;r koin fantasa pan to; oJpwsoun ejnnovhma gennhtiko;n lovgou paristavmenon: hdh d ejp touv twn kekravthke tounoma otan a levgei up ejnqousiasmou ka

pavqou blevpein dok ka up oyin tiq to akouv ousin.

The term phantasia is used generally for anything that in any way suggests a thought

productive of speech; but the word has also come into fashion for the situation in which

enthusiasm and emotion make the speaker see what he is saying and bring it visually

before his audience.

The language of sight here is familiar, and draws on the standard denitions

with which I began. Indeed, what Longinus calls the generally held denition is in fact a standard piece of Stoic philosophy. Phantasia is a central

category of Stoic psychology and optics, and the phrase a thought productive

of speech is straight out of the textbook. 13 Stoicism is in many ways the

lingua franca of the Roman Empirea pervasive intellectual discourse that

in weak form links the elite of the Roman governing class. But a further intellectual self-positioning is in evidence here, which can be seen in the marks

of debate and divisiveness around the critical vocabulary. Some people

like Plutarchblend eidolopoiein, image making, with phantasia and

enargeia. But in contemporary culture, he claims, a less philosophically

connected and more rhetorical sense of the term has prevailed. Here we see

a self-conscious awareness of shifting and different uses of rhetorical language of ekphrasis. The translation in fashion, or fashionable, which I

have taken from Russell and Winterbottom 1989, is spot on, and may even

have a slightly dismissive tone.

What is more, Longinus tries to distinguish between prose and verse (15.2):

wJ d eterovn ti hJ rJhtorikh; fantasa bouv letai ka eteron hJ para; poihta ouk an lavqoi

se, oud oti th me;n ejn poihvsei tevlo ejstn ekplhxi, th d ejn lovgoi ejnavrgeia, amfovterai

d omw tov te <paqhtiko;n> ejpizhtou si ka to; sugkekinhmevnon.

13. See in particular Long 1971a; Sandbach 1971; Watson 1988; Frede 1983; Imbert 1980; and for the

best historical overview, Rispoli 1985.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

It will not escape you that rhetorical visualization has a different intention from that of

the poets: in poetry the aim is astonishment, in oratory it is vividness. Both, however,

seek emotion and excitement.

Verse aims at ekplexisastonishmenthe claims, whereas prose looks for

vividness; by the end of the discussion, however, prose also delights in

the astounding, as he hints here, when he admits that both prose and verse

seek to move and excite. This awkwardness in terminology testies to the

ssures in the eld. Longinus, whoever he was, is not a typical intellectual

authority: he is the only pagan author to quote Genesis, and so he had direct

contact with Jewish culture and is prepared to admit it. But he does indicate

here that the language of visuality can be fraught and fought over (as one

might expect for a discourse that brings together philosophy and spectacle,

rhetoric and self-control, a heady mix that goes to the heart of Empire cultural values). Longinus lets us see a disciplinary boundary war over how to

understand ekphrastic logos, which lurks behind the apparent continuity of

denition.

Two major conclusions arise, then, from this discussion of rhetorical

theory, both of which take us far from the denitions of ekphrasis with

which we began. First, rhetorics interest in ekphrasis cannot be separated

from its understanding of enargeia and phantasia, and this means thinking

above all about the psychology of inuence. Enargeia, the arete of ekphrasis

as it is the effect of phantasia, is a way of provoking emotion, of bypassing

the intellectual and critical faculties. It sets out to make a slave of you. It

seems to me that the connection between ekphrasis, rhetoric, and the power

of emotion needs underlining.

Second, we can see also in Longinus an argument brewing over the

fashionable sense of phantasia and the Stoic philosophical sense. I do not

think these are discrete usages, as Ruth Webb does, but a conict over how

to theorize the regime of the visual and rhetorical performance in society.

Rhetorical theory does not just produce rules, of course, but seeks actively

to regulate and make comprehensible the critical scene of exchange in

Empire culture. There is a lot at stake in how persuasion works. Rhetoric is

a guide for the perplexed. That is why there is such a focus in the ancient

sources on the power of the word to astonish, confuse, and enslave.

These two points lead to a third. One of the most familiar strategies of

critical engagement with a rhetorical handbook is to extract the rules, and

then slip them like a template over a text to show how the text conforms to

the rules. QED. What I have said so far should make us feel queasy about that

rather trivial and often circular formalism. For rhetorical handbooks are also

the site of a conict over ways and means of persuasion. That is, rhetorical

theory is itself persuasive, and as such must mark the gap between itself as

theory and the performances it strives to comprehend and legislateand reproduce. Longinus is the most lyricaldazzlingof theorists, after all. It is

in this gap between the persuasive regulation of rhetorics discourse and the

performance in the courtroom or poetry salon in which the regime of the visual

is acted out. Talking proper is constructed between rules and performance

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Simon Goldhill

and is always a site of social difference and exclusion, as well as empowerment and comprehension. Theory not only provokes a complex negotiation

in and by practice, but also is part of practice. In the regime of the visual,

theory performs too.

My second area of theoretical concern is gender. The simple question here

is, To what degree is the viewing subject gendered within the ekphrastic

tradition? This may be a simple question to ask, but its ramicationsand

its answersare extremely complex, and the political and intellectual implications of such a discussion extend far beyond the Hellenistic moment

with which I am primarily concerned.

In recent years, there has been some extremely important and insightful

work on the gendering both of the voice and of the gaze; classical scholars

have learned a great deal from other elds and have themselves made signicant contributions to what is one of the most intense of contemporary

debates. 14 In classics, the question of a female voice usually starts with

Sappho, but different genres and registers of linguistic usage have also been

fascinatingly explored. Similarly Sappho has been central to discussions of

the female gaze, but both the texts of the Classical city and, in particular,

later Greek and Roman writings have been intently analyzed with regard

to the viewing subject. 15 Feminist scholarship has been to the fore here,

and much good work on the culture of viewing was initially stimulated by

critiques of the male gaze in art history and cultural studies. 16

The nineteenth century has provided a particularly stimulating test case for

the gendering of the viewing subject. The range and quality of the evidence

for this period is especially rich, and has been particularly well mined for

England and France. It is clear enough that women of different backgrounds

did look at art, and that women of varying status wrote about art in various

public and private media. There can be no doubt that institutionally the

practice of viewing was gendered: men could look at the Secret Museum of

Pompeii, for example, but women (and children) were not allowed to visit

lest they be corrupted by such sights. 17 Similarly, there was a long-running

argument about the presence of women at life classes as artists, and about

the morality of life classes per se, and the subsequent display of images of

nude women. 18 The neur was a man. 19 There is also an extensive psychological and physiological literature on the act of seeing, set against the background of the new technologies of photography and x-rays. 20 It is possible,

14. A huge bibliography could be given here. In classics, see especially McLure 1999; Lardinois and

McLure 2001; Rabinowitz and Richlin 1993; Holst-Warhaft 1992; Stehle 1997; Foley 2001; Snyder 1997,

each with further bibliography.

15. Apart from the works cited in n. 14, see, e.g., Williamson 1995; Stehle 1981; Winkler 1981; Greene

1996; Elsner 1995; Goldhill 1998; Morales 2004; Bartsch 2006; Elsner 2007.

16. See, e.g., Rose 1986; Kaplan 1983a, 1983b; Kappeler 1986; Berger 1972; Silverman 1988; Gallagher

1998; Ghose 1998; Gibson and Gibson 1993; Jay 1993; Nixon 1996; Penley 1988; Solomon-Godeau 1997.

17. Kendrick 1996.

18. See Smith 1996, esp. chap. 6, and Smith 1999.

19. Benjamin 1973, with Buck-Morss 1989, for exhaustive intellectual background. Pollock (1988)

makes the point that the neur is entirely the experiences of men, and is not really refuted by Wilson,

who argues (1992, 101) that In the department store, a woman, too, could become a neur.

20. See, e.g., Crary 1990; Clark 1984; Flint 2000; Nochlin 1989; Tagg 1988.

One Line Long

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

in short, to write a nuanced, multifaceted history of the regime of the visual

in nineteenth-century Europe, for which gender would inevitably prove a

fundamental category. In Victorian society, what is done with the eyes is

both gendered and normative.

Although the social history of viewing and the contemporary critique

of the male gaze have developed in this way extensive theoretical and

analytical resources, the positive denition of the female gaze or the

female viewing subject has proved more contentious. Even though there

are gendered social controls for how a woman in Victorian Britain views

art, it is more difcult to specify exactly howor even whethera woman

views art with a different eye from a man. It is still something of a surprise

for us, as it was for her bourgeois subjects, to recognize that Queen Victoria

was an avid collector of nudes. 21 Suzanne Kappelers searing feminist argument in The Pornography of Representation paradoxically rules out the possibility of a female viewing position when she argues that the gure behind

the cameraits viewnderis always a man (even, as it were, when it is

a woman). 22 It is a case that has provoked passionate disagreement as well

as inspiration among feminist art historians and cultural critics. 23 Does a

woman inevitably or integrally view a painting/sculpture/lm differently from

a man? If so, what are the signs, criteria, or strategies that dene the look

of a woman or the viewing position of a woman? When the same critical

vocabulary is used by a man and by a woman, does it not have the same

valence? What would be the political or philosophical implications of

claiming that a woman could look or write about looking like a man? The

positive denition of a female gaze or a female viewing subject remains

a subject fraught with conceptual and ideological contention within feminist

criticism and work inuenced by feminism.

It is against such a broad background that I turn to the more circumscribed

canvas of the Hellenistic ekphrastic tradition. For Hellenistic culture, we have,

of course, a different level and type of evidence from nineteenth-century

Europe, and in general it is a much sparser and thinner archive. But it is

possible to outline a tantalizingly fragmentary but remarkable narrative of

how women did take an increasingly active part in the institutions and performances of spectacle. 24 Women not only visited shrines and galleries,

looked at art, and wrote poetry about it, but also sponsored performances

and in rare cases performed in hitherto male preserves, such as the public

recital of epic poetry (though with the insistent patriarchy of Greece it must

also always be emphasized how remarkable the few named female artists

are). So at one level, women are certainly viewers, and the fact that women

wrote ekphrastic poetry that circulated and has survived via the canonical

anthologies is something hard to imagine for the classical polis.

But this does not answer the question of the degree to which the viewing

subject is gendered. That isto put the question in its most stark form

21. See Smith 1996.

22. Kappeler 1986.

23. See, e.g., for inspiration, Richlin 1992; for reasoned attempts to go beyond Kappeler, see, e.g.,

Braidotti 1994; Walters 1995.

24. Bremen 1996 is crucial; see also Vatin 1970; Pomeroy 1984; Burton 1995.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10

Simon Goldhill

does the existence of female ekphrastic poets necessarily indicate that there

is a viewing subject that is marked as female over and against a subject

privileged as male? The lines of the argument inevitably rehearse a familiar

debate in the politics of gender. Can we nd here a positive denition of the

female viewing subject, where women write as women? Or are ekphrastic

poets, male and female, most strongly linked by shared class, education,

and cultural and intellectual expectations? In the circle of Hellenistic Greek

society, to what degree is it possible to speak from elsewhere, to what degree

does anyone try to speak about viewing from a subject position that is not

within the cultured poses of the educated Hellenistic elite?

In an earlier piece, I looked at Herodas 4 and Theocritus 15, two poems

in which women are represented (by male poets) looking at art. In both,

the women use the language of art criticism. 25 In Herodas, I argued that the

women were mocked by the authors satire: the women in the temple were

like his women in a dildo shop. 26 Theocritus is a more complex drama, where

it is much harder to evaluate the language of criticism, and where, typically

for Theocritus, the reader nds him- or herself implicated in the represented

world of pretension and scrutiny. But in both poems the women as viewers

were seen, I argued, as Aristotle denes a womanas a deformed man. The

womens voices were marked as female only insofar as they were mocked

from the privileged viewpoint of the supposed audience. The representation of

the female voice and female gaze was a source of comedy and ironic distance,

as so often in male literature.

This view of Theocritus has recently been challenged by Marilyn Skinner,

who builds her case on the work of Kathryn Gutzwiller, Ellen Greene, and

Sylvia Barnardand her argument opens a fascinating window into the general questions I have been sketching. 27 She argues that women were able

to articulate gender-specic responses to the changing political and sexual

climate 28 of the mid-fourth to third centuries b.c.e. by writing epigrams, and

that this constitutes a specic female voice, which is testimony to a specic

female gaze. Theocritus, in Skinners view, recognizes this female tradition,

and wants to privilege the female voice as a model for sophisticated viewers.

For her, Theocritus uses women not ironically but positively as models for

viewing and thereby afrms the feminine ekphrastic tradition. 29 If Skinner

were right and there is a specically feminine ekphrastic tradition, it would

be a very important conclusion not just for our understanding of Hellenistic

culture, and for the history of ekphrasis, but also and most importantly for

the positive denition of a female viewing subject.

25. Goldhill 1994.

26. It is extraordinary that Zanker (2004, 104) thinks that this poem simply demonstrates Hellenistic

viewers responses to such statuary in general.

27. Skinner 2001; Gutzwiller 1997, 1998; Greene 2000; Barnard 1991; see also Skinner 1987, 1991;

Gutzwiller 2002.

28. Skinner 2001, 202.

29. Skinner 2001, 216. Skinner does not distinguish explicitly between feminine and female. I take

feminine here to mean not merely poetry written by women but poetry marked by values and/or qualities

associated with the female, and recognized as different from masculine values. I shall use female

throughout to indicate both the gender of the poets in question and the relevant values/attributes of their

poetry.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

11

How does Skinner make this case? She starts with Erinna, whose single

ekphrastic epigram (Anth. Pal. 6.352.14) she takes to be inaugural of a

female tradition:

Ex atalan ceirn tavde gravmmata: l ste Promaqeu ,

enti ka anqrwpoi tn oJmalo sofan:

tauv tan goun ejtuvmw ta;n parqevnon osti egrayen,

a kauda;n potevqhk, h k gaqarc ola.

This picture is the work of sensitive hands. My good Prometheus,

there are even human beings equal to you in skill.

At least, if whoever painted this maiden so truly

had just added a voice, you would be Agatharchis entirely.

Skinner claims that this is the earliest extant ekphrastic epigram. 30 She nds

the female viewing subject in the fact that the poets rsthand testimony

is crucial to the appraisal of the artistic value of the portrait: As a female

viewer . . . she stands in a privileged position with respect to the reader of

the epigram, for she alone can assure him of the pictures delity to life. 31

This, she argues, is the positing of a female viewing subject. But it is hard

here to see any specic linguistic markers of a female viewing subject. Each

and every aspect of this poems language, structure, and argument is easily

paralleled in ekphrastic writing produced by men: the praise of skillful handiwork, the address to Prometheus, the emphasis on sophia, the language of

accuracy (etumos), the conceit of adding a voice to a picture, and, above all,

the concern with verisimilitude/lifelikeness (assur[ing the reader] of the

pictures delity to life). 32 So is she a female viewer merely because she

is a woman who views (although she writes like a man)? Or can she never

write like a man because she is a womanthat is, is the language of authoritative viewing necessarily different if it comes from the mouth of a woman?

(Answering these questions is not just an issue of Hellenistic poetics, but

also a matter of the modern politics of gender.) In short, what would it take

to mark this poem as the performance of a specically female viewing

subject?

Skinner offers clearer answers to these questions with her treatment of

Anyte, one of the most interesting gures of Hellenistic culture. Anyte lived

at the beginning of the third century b.c.e. in Tegea in Arcadia. We have

about twenty epigrams transmitted under her name, and a few others where

authorship is dubious. Most of the epigrams we have are transmitted in the

Greek Anthology, and, as far as we can tell, she was the rst person to write

epigrammatic epitaphs for pets (a minor genre, of which we have also some

30. Dating of Erinna depends on the Suda, and the transmission of epigrams is dependent on anthologization in the main, so it is always hard to prove the protos heuretes. But there is no reason to doubt that

this is a very early example of ekphrastic epigram.

31. Skinner 2001, 209.

32. For this language, etumos in particular in art criticism, see Pollitt 1974; for the pervasiveness of the

tropes of realism, see Zanker 1987 (nice joke on this topos at Anth. Pal. 9.215); for Prometheus reference,

cf. Anth. Pal. 9.724; for the soft hands, cf. Anth. Pal. 9.544; the proclamations of techne and sophia are

multiform, see Goldhill 1994.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12

Simon Goldhill

later examples). She also wrote some epigrams that praise pastoral temple

groves and similar scenes, which leads Skinner to hail her as the acknowledged inventor of the pastoral epigram. 33 Gutzwiller indeed celebrates Anyte

as the rst epigrammatist to present a distinct literary persona, 34 and the

rst to write a book of epigrams as such. 35 In the hunt for a female viewing

subject, Anyte is the linchpin between Sappho and gures like Nossisa

female line of female poets with a specic female voice.

Skinner offers several paths towards a positive denition of Anyte as a

specically female viewing subject. Anytes most important contribution

to the construction of the female viewer is her introspective approach to

ekphrases of paintings and statues. 36 As Gutzwiller writes, Anyte presents

for us, not an accurate description of an artwork, but an imaginative interpretation that arises from her own unique perspective on the represented gure. 37

Nossis is no less innovative, adds Skinner, because her poems express

the speakers reaction to the sight of painted portraits and other temple

offerings made by women. 38 This argument again shows how difcult it is

to develop a specic positive denition of what makes up the female voice/

the female viewing subject. For the vast majority of ekphrastic epigrams are

written by men, and the vast majority of ekphrastic epigrams offer an

imaginative interpretation based on a unique perspective, just as the vast

majority of ekphrastic epigrams dramatizing an encounter with a picture

express the speakers reaction, and there are innumerable epigrams on

female dedications by male poets ( just as female poets write about spears,

hunting animals, and other objects that would routinely be associated with

the male sphere). The attempt to dene the specically female viewing subject

again runs up against the fact that the language, form, subject matter, and

structure of the epigrams are common to male and female writers.

Skinner offers three more attempts to nd a positive denition of the specically female viewer in Anytes work, but each of these arguments struggles

unconvincingly in its search. First, she declares that there is in Anyte a female

aesthetic: the qualities for which particular votive offerings are admired

chiey the neness of the workmanshipdene a specically female aesthetic

that may be traced back, again, to Erinna. 39 If praise for the neness of

workmanship is specically female, then almost all ekphrastic writers

back to Homer and forward to the Christian epigrammatists would share in

this aesthetic. Fineness of workmanship simply cannot be treated as a

specically female criterion. For the general point here, the contrast

with the Victorian material is perhaps useful. In Victorian writing a female

aesthetic is recognized explicitly: there are long discussions, for example,

of the lady novelist, of a womans particular sense of sympathy and emotion

33. Skinner 2001, 209; see Gutzwiller 1998, 5474, for the most detailed discussion of Anyte.

34. Gutzwiller 1998, 55.

35. These grandest claims are criticized by Hunter (1998).

36. Skinner 2001, 209; see also Skinner 1989.

37. Gutzwiller 1998, 68.

38. Skinner 2001, 209.

39. Skinner 2001, 211.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

13

as a reader and writer, along with repeated examples of the denigration of the

female as falling short of the male. 40 But there is no such discussion in the

ancient material, nor even hints of a discussion now lost to us. In the face

of such silence, it will always be extremely difcult to dene a specically

female aestheticand dangerous to read back from the nineteenth century

to the ancient world. 41

Second, Skinner claims that the subject matters chosen by Anyte (and

Nossis) are specically female: in particular, poems on pets mark a womans

voice because of their sympathetic approach to dogs and other animals. 42

There are many ways that women and animals are linked in the Greek cultural imagination, but the locus classicus for someone letting slip a tear over

the death of a beloved animal is Odysseus in the Odyssey with his dog Argus.

Anytes poem on the dead dog is not included in the Hellenistic anthologies

but is quoted by Pollux (5.48), who precedes it with a quatrain by Simonides

that also mentions the dogs grave. It is in a section on famous dogs,

which gives no indication that remembering dogs (or other pets) with

emotion is a female preserve. What is more, her poem on the little girl Myro

burying her pet locust and cicada is attributed to Anyte or Leonidas by

the manuscripts and is imitated by Marcus Argentarius (Anth. Pal. 7.364).

It would be hard to claim that there is any ancient recognition of anything

specically female in these poems.

Third, Skinner imagines that these poems were performed in what she

calls a community of women, a female voice speaking . . . to an audience

of female listeners. 43 We should, that is, read this poetry as womens talk

as opposed to mens talk, women around the loom rather than men at the

symposium. There is, however, no evidence offered for such a special female

community for new poetry 44 (although there is fascinating evidence in the

Hellenistic period for female poets performing in the most public of all

genres, epic), 45 and since most of Anytes epigrams are in public genres 46

epitaphs and the likeit is extremely hard to see them as being produced for

any particular group. Indeed, such a hypothesis would require us to ignore

the evidence we do havethe extensive collection of poems and other

40. See Helsinger, Sheets, and Veeder 1983, vol. 3, esp. pp. 378. Showalter 1977 remains basic here.

41. The most famous example of anachronistic searches for a female aesthetic is Samuel Butlers argument

that the Odyssey must have been written by a woman because of its interest in perfume and jewelry.

42. Barnard (1991) puts this most navely; Gutzwiller (1998) more cautiously.

43. Skinner 2001, 210; of Nossis she speaks even more strongly (1991, 21): writing directed exclusively

towards a relatively small, self-contained female communitydespite the poems being in the form of

public dedications.

44. Skinner suggests (2001, 211) that the rst-person plural in Nossis 4 indicates a female community.

But if it is not a generalizing plural, it indicates a group of women visiting a shrine, a choros or theoria,

and indicates nothing of the necessary audience: cf Alcman, where the female chorus refer to themselves as

we, but where there is no suggestion that the audience is solely female. Men do write in the rst-person

plural in the persona of a woman (Anth. Pal. 9.418), and more regularly in rst-person singular (Anth. Pal.

7.493, 6.74, 9.254, 9.260); even, with pleasing irony, referring to what may not be talked of by men

(Anth. Pal. 6.210).

45. I am thinking of Aristodama (IG 9.2.62, 9.12.740), who was awarded citizenship rights for her performances of epic poetry.

46. See Stehle 2001.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14

Simon Goldhill

inscriptions on gravestones that lament the passing of women by husbands,

sons, and by women, for at least three hundred years before Anyteall public

monuments. (Unfortunately, Skinner does not mention the relevant material

culture.) It is these epitaphs on stone, written by men, that Anyte and other

epigrammatists imitate.

Finally, it must be stressed how difcult it is in the ancient sources to see

any recognition of a female ekphrastic tradition as a tradition. Antipater writes

a well-known epigram (Anth. Pal. 9.26) in which he lists nine women poets

as the equivalent of the nine Muses (and labels Nossis with the intriguing

adjective theluglossos, female-voiced: is she female-voiced in any way

that the other eight are not? 47). Erinna is compared to Sappho in another

epigram (where she is also likened to Homer, Anth. Pal. 190), and Nossis

makes reference to Sappho as the rst and greatest female poet (Anth. Pal.

7.718). 48 Sapphos poetry is often lavishly praised by men, but the language

of praise does not articulate a specically gendered vocabularydespite

the fact that in the comic tradition it is always possible to mock Sappho in

sexualized and gendered terms. So, where Nossis and Erinna are mentioned

together by Herodas, it is for the sake of a bawdy and derogatory joke. 49

But there is no recorded reference to a female ekphrastic tradition.

To evaluateand validatewhat is special about these remarkable female

poets is an important task to undertake. The very existence of Erinna, Anyte,

and Nossis in Greek patriarchal society remains a precious and signicant

testimony of the shifting possibilities for female engagement in Hellenistic

cultural life. There are no equivalents in the classical polis. But within these

womens poems it proves extremely hard to nd a positive denition of the

female viewing subject. Since the language and strategies of expression in

the poetry of Erinna, Anyte, and Nossis are so similar to that of male epigrammatists, and since there is no explicit recognition of a specically female

viewing subject or a female ekphrastic tradition, Skinners claims for a specically marked female viewing subject seem to have no solid foundation.

To answer my question to what degree is the viewing subject gendered

within the ekphrastic tradition? we have searched for but failed to nd a

practice and language of viewing that is marked or recognized as specically

female by its linguistic register or its rhetoric or its stance.

But this is not a simply negative conclusion: rather it takes its force from

a long-running feminist debate about dominant discourse. 50 For the degree

to which male and female sophoi actually share the authoritative language

and rhetoric of ekphrastic viewing is in itself signicant. It shows how even

or especiallyin the changing social and intellectual conditions for women

in Hellenistic culture, women are implicated in the dominant (intellectual)

discourse. These elite womenand we must assume that these epigrammatists were members of the elite classspoke the same language as the elite

47. Discussed in Skinner 1987. Analogous compounds such as heduglossos or barbaroglossos make it

highly unlikely that it means speaking to women, as she claims.

48. As well as Gutzwiller 1998, and the works of Skinner already cited, see Bowman 1998.

49. Discussed by Skinner 1991.

50. Irigaray 1985 is particularly inuential here.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

15

male epigrammatists. That these women did not write in a subversive or

marked way, except by the very fact of being women (which is important

enough in itself ), is a telling sign of the dominance of paideia (Bildung)

as a culturally homogenizing force, and of the difculty of nding a place

outside this patriarchal, cultural world from which to speak. (The problem of

nding a place from which to speak that is not already incorporated into the

dominant structures of authority is a familiar struggle in [feminist] politics,

and it is a problematic with which the scholarly academy is particularly engaged.) It might be less inspirational, less exciting, to nd no marked female

viewing subject in these ekphrastic poems, but it may also be a more accurate

expression of the power politics of culture.

Therefore, I remain unconvinced that Theocritus poetry should be understood through postulating a feminine ekphrastic tradition. The female

viewers of the palace spectacle in Idyll 15 (or of the temple pictures in

Herodas 4) are not privileged models to guide the male reader, as Skinner

proposes. The representation of the female viewers here remains full of the

ironic mockery of a sophisticated mime. As so often with comedy, mockery

has a socially normative effect.

What I have done so far is to look rst at rhetorical theorywhere we saw

rhetoric providing not so much a rule book for writing ekphraseis, as a way

of exploring the productive gap between theory and performance, especially

with regard to that critical moment of being emotionally persuasivepsychologically blindingthrough visualization. Second, we looked at whether

a female viewing subject could be recognized in the ekphrastic tradition.

Despite all the evidence for the privileged institutional and intellectual

position of the male, and despite the remarkable ourishing of Erinna,

Anyte, and Nossis against such a background, it was extremely hard to nd

any positive denition of a marked female viewing subject, except as a

parody of the male voice. It is hard to imagine that any of our epigrams, discovered without an author, could be safely declared to be by a female writer

on aesthetic or rhetorical grounds.

II

For the second and nal section of this article, I want to take a brief look at

the most extraordinary anthologized collection of ekphrastic epigrams in the

light of the general discussion of my opening section. This collection is the

thirty-six poems on Myrons Cow (Anth. Pal. 9.71342, 79398).

Let me offer some general points to start with.

First, it is clear that detached and strictly empirical report of visual experience is nowhere to be seen in this string of poems (all by men). It is impossible to make any sensible reconstruction of the sculptureas people try

to do, for example, with Philostratus Imagines. 51 It is a small cow. No more,

no less can be gleaned, except that it stands on a base. What these poems do

is something else.

51. As discussed by Bryson 1994.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16

Simon Goldhill

So, second, what do they do? They all respond to the work by offering

tropes of verisimilitude. This cow looks so real that . . . is the starting point

for nearly all of them. So Demetrius of Bithynia (Anth. Pal. 9.730), in the

voice of the cow, writes: If a calf sees me, it will low; a bull will mount me,

and the herdsman will drive me to the herd. Or Anth. Pal. 9.720 by Antipater

of Sidon: If Myron had not xed my feet to this stone, I would have gone

to pasture with the other cows. But the twists on this are multiform. In particular, the ekphrastic poets love to play with the very language of art history

to create specic intellectual games on the theme of verisimilitude. So Evenus

(Anth. Pal. 9.717, 718) offers two contrasting poems:

H to; devra cavlkeion olon boi td ejpkeitai

ektoqen, h yuch;n endon oJ calko; ecei.

Either a complete bronze hide lies on this cow

On the outside, or the bronze has a soul in it.

Auto; ejre tavca touto Muv rwn: ouk eplasa tauv tan

ta;n davmalin, tauv ta d ekovn aneplasavmhn.

Perhaps Myron himself will say this: I did not fashion

This heifer, but I fashioned the image of her.

In the rst, he plays an inside/outside game around bronze castingand the

potential of art to reveal the soul, which is the lure of realism, as Xenophon

made clear back in the fourth century. 52 Is the hide a bronze skin that conceals

a real cow? Or does bronze have soul, life in it? In the second, Myron

himself is supposed not to recognize his own work but to think it is the model

from which he made his statue. A sophisticated reversal of the language of art

history: it is so lifelike that its creator is deceived and assumes it is the archetype of his own image. In Anth. Pal. 9.719, the cow itself thinks it is real

and that Myron lied when he said he made it:

Ouk eplasevn me Muv rwn, ejyeuv sato: boskomevnan de;

ejx agevla ejlavsa dhse bavsei liqn.

Myron did not fashion me; he lied. Rather, he drove me from the herd

Where I was grazing, and xed me to a stone base.

This is a neat twist on the falseness of art. Pseudomai is the technical term

for arts deceptiveness and often associated negatively with the ctive quality

of art, for which plasso is the proper termto fashion or mold, as in

Anth. Pal. 9.718 also. 53 Here the vertiginous conceit of the poet is that the

cow really is real, and therefore she accuses the artist of lying and not

fashioningor so the lying poet fashions.

Anth. Pal. 9.798, by Julian the Prefect, also plays with the vocabulary of

art history:

52. Mem. 3.10, as discussed by Rouveret 1989.

53. And Anth. Pal. 7.724, discussed below, as well as 7.726 and 7.736; Myron is called plavsth,

(sculptor) in 7.723, 732, and 796. See Gill and Wiseman 1993.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

17

Tlhqi, Muv rwn: tevcnh se biavzetai: apnoon ergon.

ejk fuv sew tevcnh, ou ga;r fuv sin eu reto tevcnh.

Bear up, Myron. Art defeats you. The work is lifeless.

Art is from nature. For art did not discover nature.

Myron should bear up. Art (techne) has defeated him. The work is lifeless. Julian wittily reverses the expectations of the narrative of realism. As

Art comes from Nature, Art cannot invent Nature. This is a more philosophically loaded response than the others I have considered so far. It playfully

manipulates the opposition of phusis and techne (as does Daphnis and Chloe),

but still comforts Myron for his failure to produce a breathing sculpture.

These epigrams do not merely play with the notion of lifelikeness, but

do so through and with the technical language of art history to create a specically intellectualized and sophisticated response, and, crucially, this

response is not to art but to the tropes of verisimilitude. It is far from clear

that any one of these poets from around the world had to have seen the

sculpture in Athens. But they all have read each others ekphrastic poetry

and some art history.

The third point is that each poem is constructed as a specic type of scene

or exchange. Each dramatizes an inherent you might have thought, or you

might say, only to trump it with a more pointed, cleverer retort. So Antipater in Anth. Pal. 9.722 tells the cowherd not to whistle at the sculpture:

Ta;n davmalin, bouforbev, parevrceo mhd apavneuqe

sursd: mast povrtin upekdevcetai.

Pass by the heifer, cowherd, and do not whistle to her

from afar. She is expecting the calf to suckle.

The presupposition is the cowherd might be about to. . . . But Antipater then

adds the surprising reason: her calf is going to suckleas if a baby cow, the

sculpture, and maybe even the poet himself are fooled by the realism. The

rst suggestion of a misplaced realismthe country cowherd shouldnt

whistle at a sculptureturns out to be a foil for a more baroque hyperrealism where even the sculpture itself shares in the illusion.

The scene can be the poets own reactionas in Anth. Pal. 9.724 by

Antipater:

davmali, dokevw, mukhvsetai: h rJ oJ Promhqeu;

ouc movno, plavttei empnoa ka suv , Muv rwn.

I think the heifer will moo. Truly, Prometheus is not the only one

To fashion living things, but you too, Myron.

The familiar appeal to realism is immediately framed by a mythological, intellectual point. Myron is like Prometheus, artistic creativity incarnate.

At very least, each poem imagines some sort of exchange: the cow

addresses the reader; the poet addresses a herdsman; the poet addresses an

interlocutor. We are here in the world of the pepaideumenos, the cultivated

intellectual about town with his pals. Each epigram performs what Lucian,

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18

Simon Goldhill

the second-century satirist, tells us is the mark of the cultured viewer. 54

You should not stand and stare awestruck before art, waving your hands

ineffectually; you should stand rm and speak. Art should produce commentary. That is how cultivation is displayed to an audience and regulated.

Fourth, the work of anthologizing itself is also integral. These poems are

put together for a reason. We are given a resource, a handbook, a map of how

to do things. This is not just a display of the rhetorical invention of a group

of poetsthough copia, inventio, and variatio are rhetorical values. Rather,

it is establishing a ground for response. The very variety of response is a

sign of the intellectual sophia involved in art history. It shows that there

cannot be one response only, which means we need to enter the world of

competitive critical positionsmutual scrutiny, mutual regulation, mutual

admiration, that is, all the aspects of a discipline in action. The anthology itself

wants to put each reader in a position where s/he has to join in by adding

to it, selecting from it, mapping a route through it. Anthologies do things to

the reader.

Fifth, these poems are competitive. They are competitive rst and most

obviously in that each poet writes in knowledge of the others, aiming for the

best response. They are also competitive, however, in the struggle to get the

response rightwith themselves as it were. So Julian the Prefect of Egypt

writes eight poems, each giving a different slant (Anth. Pal. 9.73839, 793

98S). So Anth. Pal. 9.797, like Anth. Pal. 9.730 translated above, runs together

three versions of the trope of mistaking the sculpture for the real thing (in

the voice of the sculpture): When I am seen, a lion opens wide his mouth,

a farmer reaches his hands for the yoke, a herdsman picks up his crook.

The cowherd is addressed in Anth. Pal. 9.794 (as in 9.722, discussed above)

and told not to try and drive off the sculpture since art did not bestow

motion on me tooa neat reference back to Daedalus and his moving

sculptures. As we have seen, he also offers a more art-historical response,

Anth. Pal. 9.798. He too wonders if the bronze is alive or if a live heifer has

been cast in bronze (Anth. Pal. 9.795). He also dramatizes the moment of

response vividly (Anth. Pal. 9.793):

Povrtin thvnde Muv rwno dw; n tavca tou to bohvsei

H fuv si apnoov ejstin, h empnoo epleto tevcnh.

When you see this heifer of Myron, you will perhaps shout:

Either Nature is lifeless, or Art is alive.

The viewer is to respond loudly with a sophisticated witticism, reworking

the terms of nature and art, lifeless and alive familiar from other

epigrams.

Sixth, and following on from this last point, these poems are directive.

They want you to respond in a particular way. The viewing subject is an

articulate, educated chap, and these poems tell you, individually and collectively, what sort of response to have. They set out to make you a viewer

like this. Epigrams are brief, but they are both agonistic and normative.

54. Discussed in Goldhill 2001a.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Is Ekphrasis For?

19

Finally, we must consider how these epigrams may relate to the rhetorical

theory with which I began. The agonistic and normative force of the epigrams is perhaps one place where we can see these little poems touching on

the rhetorical theorists claims that visualization is a means of violent distraction of the audience away from facts or proof and towards emotion.

Such epigrams are not, of course, the grand emotional displays of Thucydides

or the masters of the courtroom. But wonder and astonishment are repeatedly the basis of response here too, and they are certainly persuasive, and

within their brief scope epigrams do try to summon feelings in the reader of

awe, or fear or surprise or erotic desire (as Gutzwiller has discussed briey

but pertinently). 55 They want you to see things in a particular way and feel

things in a particular way. But even if we do recognize thus an echo of that

theory in these works, the different level of instantiation is also striking and

emphatic. Ekphrastic epigrams are a privileged mode of ekphrasis in this

period, but they do not t comfortably into the grander rhetorical theories

of visualization. There is a gap between the theory of the rhetorical handbooks and the practice of these epigrammatists. The poems echo with the

language of rhetorical training and art history but do not simply conform to

the rules promoted by either discipline. The development of a regime of the

visual works in this gap between theory and practice. The viewing subject

of Hellenistic culture is produced in the interrelations between the grand

set pieces of history and oratory, the deliberately small-scale epigrams, the

studied theory that gives an intellectual frame for such worksall set in

the social world of display and ceremonial. The interconnections here,

which I have so summarily outlined, must be built into any account of how

ekphrasis functions in Hellenistic culture.

The reading and production of ekphrastic epigram is part of a system that

functions to produce a cultivated and cultured citizen of Empire, who knows

how to perform in the world of culture and who knows thus how to play the

game of competitive self-scrutiny as a performer in culture. And that is what

I think ekphrasis is for. 56

Kings College, Cambridge

55. Gutzwiller 2002, 94104.

56. This article was rst developed for the Passmore Edwards conference on ekphrasis in Oxford (2003).

Thanks to Ja Elsner for the invitation and subsequent editorial advice, to Richard Hunter for comments,

and also to Helen Morales for extended discussion.

This content downloaded from 95.47.151.199 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 04:27:38 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The City as Comedy: Society and Representation in Athenian DramaDe la EverandThe City as Comedy: Society and Representation in Athenian DramaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Florentine Camerata and The Restoration of Musical AesDocument8 paginiThe Florentine Camerata and The Restoration of Musical Aesalxberry100% (1)

- The History of Rome (Complete Edition: Vol. 1-5): From the Foundations of the City to the Rule of Julius CaesarDe la EverandThe History of Rome (Complete Edition: Vol. 1-5): From the Foundations of the City to the Rule of Julius CaesarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alexander and OrientalismDocument4 paginiAlexander and OrientalismvademecumdevallyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proceedings of the 31st Annual UCLA Indo-European ConferenceDe la EverandProceedings of the 31st Annual UCLA Indo-European ConferenceDavid M. GoldsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre GreekDocument34 paginiPre Greekkamy-gÎncă nu există evaluări

- Augustus and the destruction of history: The politics of the past in early imperial RomeDe la EverandAugustus and the destruction of history: The politics of the past in early imperial RomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reincarnare OrfismDocument14 paginiReincarnare OrfismButnaru Ana100% (1)

- Foundation Myths in Ancient Societies: Dialogues and DiscoursesDe la EverandFoundation Myths in Ancient Societies: Dialogues and DiscoursesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hybris in Athens: An Analysis of the Ancient Greek ConceptDocument19 paginiHybris in Athens: An Analysis of the Ancient Greek ConceptrmvicentinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electra and the Empty Urn: Metatheater and Role Playing in SophoclesDe la EverandElectra and the Empty Urn: Metatheater and Role Playing in SophoclesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lefkowitz: Influential WomenDocument9 paginiLefkowitz: Influential WomenΑγλαϊα ΑρχοντάÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dance (by An Antiquary) Historic Illustrations of Dancing from 3300 B.C. to 1911 A.D.De la EverandThe Dance (by An Antiquary) Historic Illustrations of Dancing from 3300 B.C. to 1911 A.D.Încă nu există evaluări

- Horace and His Influence by Showerman, GrantDocument71 paginiHorace and His Influence by Showerman, GrantGutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cicero's Philippics and Their Demosthenic Model: The Rhetoric of CrisisDe la EverandCicero's Philippics and Their Demosthenic Model: The Rhetoric of CrisisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foley Homer Through Oral TradDocument29 paginiFoley Homer Through Oral TradOleg SoldatÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Deipnosophists, or Banquet of the Learned of AthenæusDe la EverandThe Deipnosophists, or Banquet of the Learned of AthenæusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sideshadowing in Virgil's AeneidDocument18 paginiSideshadowing in Virgil's AeneidcabottoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre-Greek Loanwords in Greek (Beekes)Document31 paginiPre-Greek Loanwords in Greek (Beekes)TalskubilosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Shroud and The Trope - Representations of Discourse and of The Feminine in Homer's OdysseyDocument8 paginiThe Shroud and The Trope - Representations of Discourse and of The Feminine in Homer's OdysseyLiteraturedavid100% (1)

- The Panathenaic Games: Proceedings of an International Conference held at the University of Athens, May 11-12, 2004De la EverandThe Panathenaic Games: Proceedings of an International Conference held at the University of Athens, May 11-12, 2004Încă nu există evaluări

- The Homeric Narrator and His Own KleosDocument21 paginiThe Homeric Narrator and His Own KleosTiago da Costa GuterresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matrices of GenreDocument1 paginăMatrices of GenreMelina JuradoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theocritus Idyll 11Document3 paginiTheocritus Idyll 11Brittany LeighÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHIASMUS IN ANCIENT GREEK AND LATIN LITERATUREDocument19 paginiCHIASMUS IN ANCIENT GREEK AND LATIN LITERATUREnatsugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hayes-Martial The Book Poet PDFDocument197 paginiHayes-Martial The Book Poet PDFMarcus Annaeus LucanusÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Hellenic Studies) Gregory Nagy - Plato's Rhapsody and Homer's Music - The Poetics of The Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens (2002, Center For Hellenic Studies)Document21 pagini(Hellenic Studies) Gregory Nagy - Plato's Rhapsody and Homer's Music - The Poetics of The Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens (2002, Center For Hellenic Studies)yakarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aeneid book 4 vocab overviewDocument9 paginiAeneid book 4 vocab overviewGayatri GogoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lycian CivilizationsDocument648 paginiLycian CivilizationsCemre Ekin GülerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allen, W. - The Epyllion - TAPhA 71 (1940)Document27 paginiAllen, W. - The Epyllion - TAPhA 71 (1940)rojaminervaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bacon Furies - Homecoming Ocr PDFDocument13 paginiBacon Furies - Homecoming Ocr PDFΌλοι στους ΔρόμουςÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alexander StoriesDocument8 paginiAlexander StoriesAlejandro J. Garay HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burnett ArchilochusDocument21 paginiBurnett ArchilochusmarinangelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Egyptian Hieroglyphs Found at MycenaeDocument7 paginiEgyptian Hieroglyphs Found at MycenaeNițceValiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speeches in The HistoriesDocument13 paginiSpeeches in The HistoriesJacksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Last Days of The Pylos Polity," in R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier Eds., Politeia Society and State in The Aegean Bronze Age, Aegaeum 12 (Liège 1995) 623-633, Plate LXXIV.Document16 paginiThe Last Days of The Pylos Polity," in R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier Eds., Politeia Society and State in The Aegean Bronze Age, Aegaeum 12 (Liège 1995) 623-633, Plate LXXIV.Olia Ioannidou100% (1)

- Broggiato - 2011 - Artemon of Pergamum (FGRH 569) - 1Document8 paginiBroggiato - 2011 - Artemon of Pergamum (FGRH 569) - 1philodemusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Invention Homer PDFDocument20 paginiInvention Homer PDFmarcusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robert Graves - The Greek MythsDocument219 paginiRobert Graves - The Greek MythsMetin Ozturk100% (1)

- GREEK DIALECTS - Gregory NagyDocument212 paginiGREEK DIALECTS - Gregory NagyRobVicentin100% (1)

- Humanistica Lovaniensia Vol. 35, 1986 PDFDocument334 paginiHumanistica Lovaniensia Vol. 35, 1986 PDFVetusta MaiestasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Galinsky 1968 Aeneid V and The AeneidDocument30 paginiGalinsky 1968 Aeneid V and The AeneidantsinthepantsÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Supplementa Humanistica Lovaniensia, 12) Gilbert Tournoy - Dirk Sacré - Ut Granum Sinapis - Essays On Neo-Latin Literature in Honour of Jozef IJsewijn (1997, Leuven University Press) PDFDocument380 pagini(Supplementa Humanistica Lovaniensia, 12) Gilbert Tournoy - Dirk Sacré - Ut Granum Sinapis - Essays On Neo-Latin Literature in Honour of Jozef IJsewijn (1997, Leuven University Press) PDFIanua ViteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prometheus Bound PDFDocument257 paginiPrometheus Bound PDFĶľéãÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gods in The 'Aeneid'Document27 paginiThe Gods in The 'Aeneid'markydee_20Încă nu există evaluări

- FlaccusDocument529 paginiFlaccusGelu Diaconu100% (1)

- PDFDocument11 paginiPDFamfipolitisÎncă nu există evaluări

- British School at AthensDocument7 paginiBritish School at AthensPetrokMaloyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Story of Educational Philosophy in AntiquityDocument21 paginiA Story of Educational Philosophy in AntiquityAngela Marcela López RendónÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Interpretation of The Hippolytus of Euripides Author(s) : David GreneDocument15 paginiThe Interpretation of The Hippolytus of Euripides Author(s) : David GrenepriyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Complete Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley - Complete by Shelley, Percy Bysshe, 1792-1822Document1.028 paginiThe Complete Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley - Complete by Shelley, Percy Bysshe, 1792-1822Gutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- North - 2008 - Caesar at The LupercaliaDocument21 paginiNorth - 2008 - Caesar at The LupercaliaphilodemusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Denys Lionel Page - Sappho and Alcaeus - An Introduction To The Study of Ancient Lesbian Poetry-Clarendon Press 1955Document348 paginiDenys Lionel Page - Sappho and Alcaeus - An Introduction To The Study of Ancient Lesbian Poetry-Clarendon Press 1955Jose Miguel Gomez ArbelaezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simulacra Gentium. The Ethne From The Sebasteion at Aphrodisias. R. R. Smith PDFDocument23 paginiSimulacra Gentium. The Ethne From The Sebasteion at Aphrodisias. R. R. Smith PDFjosephlarwen100% (2)

- Marco Ercoles. Aeschylus' Scholia and The Hypomnematic Tradition: An InvestigationDocument43 paginiMarco Ercoles. Aeschylus' Scholia and The Hypomnematic Tradition: An InvestigationΘεόφραστος100% (1)

- Deucalion Pyrrha Ransmayr CelanDocument14 paginiDeucalion Pyrrha Ransmayr CelanNepomuk NeuschmiedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bacchylides, Ode 17 (Dithyramb 3)Document9 paginiBacchylides, Ode 17 (Dithyramb 3)Dirk JohnsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structure and Meaning in Medieval Arabic and Persian PoetryDocument522 paginiStructure and Meaning in Medieval Arabic and Persian PoetrypoomerangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kavcic, The Decline of The Aorist Infinitive in Ancient Greek Declarative Infinitive Clauses, JGL 2016 PDFDocument46 paginiKavcic, The Decline of The Aorist Infinitive in Ancient Greek Declarative Infinitive Clauses, JGL 2016 PDFJesus MccoyÎncă nu există evaluări