Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

Încărcat de

JoelOlivoDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

Încărcat de

JoelOlivoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Revista de Psicologa Social / International Journal of Social Psychology, 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2014.972707

Spanish adaptation of the Antifat Attitudes Scale / Adaptacin al

castellano de la Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

Alejandro Magallares and Jose-Francisco Morales

Universidad Nacional de Educacin a Distancia

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

(Received 5 March 2013; accepted 10 July 2013)

Abstract: Antifat attitudes may be defined as the negative assessment of

people with weight problems. To evaluate them, the Antifat Attitudes Scale

(AFA) has been used in most studies. The aim of this study is to adapt the

AFA questionnaire to the Spanish population. The sample was made up of

1,457 university students from all over Spain. Exploratory and confirmatory

factor analyses showed that the items on the questionnaire fit a three-factor

model corresponding to the three dimensions proposed by the original

author (dislike, fear of fat and willpower) and that they are interrelated. In

light of these results, we conclude that the questionnaire is methodologically

valid and can be used by the scientific community to measure antifat

attitudes.

Keywords: antifat attitudes; confirmatory factorial analysis; exploratory

factorial analysis; obesity

Resumen: Las actitudes antiobesos se definen como la evaluacin negativa

que se realiza de las personas con problemas de peso. La mayora de los

estudios han empleado la Antifat Attitudes Scale (AFA) para medirlas. El

objetivo del presente trabajo es adaptar al castellano la citada escala. Para ello

se recogieron datos de 1.457 estudiantes universitarios de diferentes ciudades

espaolas. Los resultados de los anlisis factorial exploratorio y confirmatorio

muestran que los tems del cuestionario se ajustan a un modelo de tres

factores, correspondientes a las tres dimensiones originales propuestas por el

autor (Antipata, Miedo a la Gordura y Voluntad), que estn relacionados

entre s. De acuerdo con estos resultados, se concluye que el cuestionario es

metodolgicamente vlido y que puede ser utilizado por la comunidad

cientfica para medir actitudes antiobesos.

Palabras clave: actitudes antiobesos; anlisis factorial confirmatorio; anlisis

factorial exploratorio; obesidad

English version: pp. 111 / Versin en espaol: pp. 1222

References / Referencias: pp. 2225

Translated from Spanish / Traduccin del espaol: Mary Black

Authors Address / Correspondencia con los autores: Alejandro Magallares, Departamento

de Psicologa Social y de las Organizaciones, Facultad de Psicologa UNED, C/Juan del

Rosal, 10, 28040 Madrid, Espaa. E-mail: amagallares@psi.uned.es

2014 Fundacion Infancia y Aprendizaje

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Obesity is defined as an excessive accumulation of adipose tissue which translates

into an increase in body weight (World Health Organization, 2000). The most

frequent cause of this disease is exogenous or nutritional, although it may also be

the result of certain endocrinal diseases (hypothyroidism, Cushings syndrome,

primary hypogonadism or polycystic ovary syndrome), genetic syndromes

(Laurence-Moon-Bielde, Alstrm or Prader-Willi syndrome) or hypothalamic

lesions (Haslam & James, 2005). In addition, it is important to stress that obesity

is associated with a variety of illnesses (known as comorbidities) such as dyslipidaemia, type-2 diabetes, high blood pressure, degenerative arthropathy and

sleep apnea syndrome (Guh et al., 2009).

The prevalence of obesity in Western countries is truly high (King, 2011). In

Spain, recent studies revealed that 34.2% of the population carries excess weight,

while the obesity rate is 13.6% (Rodrguez-Rodrguez, Lpez-Plaza, LpezSobaler, & Ortega, 2011). If we compare the current situation with the first studies

conducted on this topic in Spain (Aranceta et al., 1998), we can see a striking rise

in the number of obese people (Basterra-Gortari et al., 2011), which gives an idea

of the magnitude this problem is reaching. Therefore, obesity is a problem with

medical origins that has also become a social problem over time in that it is

affecting more and more layers of the population. For this reason, it is particularly

important to examine peoples behaviour with the obese, since some studies reveal

that obese people are socially stigmatized (Puhl & Heuer, 2009).

Discrimination against obese people

The scholarly literature analysed reveals that obese people suffer from discrimination in many social areas (Puhl, Heuer, & Brownell, 2010). In the area of

health, we can see that healthcare professionals share a series of negative beliefs

about the obese (they tend to think of their obese patients as lazy and unintelligent, similar to the prevailing social stereotype), which ends up affecting the

treatment that patients with weight problems receive (Huizinga, Bleich, Beach,

Clark, & Cooper, 2010). There is also such a negative stereotype of obese

workers at the workplace (they are believed to be slower and clumsier than

other people) that it is practically impossible for overweight people to share

equal conditions with others in the job market (Agerstrm & Rooth, 2011).

Generally speaking, it has been found that obese people have problems in staff

hiring processes, earn less, hold lower-ranking jobs and suffer from a higher

unemployment rate. Research in the field of education has also found widespread prejudice towards overweight children (Turnbull, Heaslip, & McLeod,

2000). In the sphere of interpersonal relations, similar results have been found:

overweight people are treated more negatively than people with a lower body

weight (Hersch, 2011). Finally, the image of overweight people shown in the

media is often negative, and this contributes to disseminating stereotypes of the

obese (McClure, Puhl, & Heuer, 2011). It is important to stress that many of

the studies listed here have been conducted in English-speaking environments,

although there are also studies in Spain on the existence of prejudice towards

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

obese people in many of the social areas mentioned above (Juregui-Lobera,

Rivas-Fernndez, Montaa-Gonzlez, & Morales-Milln, 2008).

It is particularly important to mention that many studies relate the discrimination suffered by the obese with overweight peoples decline in quality of life

(Ashmore, Friedman, Reichmann, & Musante, 2008). For all of these reasons, the

field of social psychology has deemed it necessary to study prejudice towards the

obese (Crandall, 1994). A series of questionnaires has been designed to analyse

the assessments of people with weight problems, including the Antifat Attitudes

Scale (Crandall, 1994).

Antifat attitude scales

Today there are many instruments available in the scholarly community to

measure antifat attitudes. They include, but are not limited to, the Beliefs About

Obese Persons Scale (BAOP, Allison, Basile, & Yuker, 1991), the Attitudes

Toward Obese Persons Scale (ATOP, Allison et al., 1991), the Anti-fat Attitudes

Scale (AFAS, Morrison & OConnor, 1999), the Anti-fat Attitudes Test (AFAT,

Lewis, Cash, & Bubb-Lewis, 1997) and the Fat Phobia Scale (Bacon, Scheltema,

& Robinson, 2001). However, the most widely used scale is the Antifat Attitudes

Scale (AFA, Crandall, 1994).

In 1994, Christian Crandall developed a scale to measure prejudice against

obese people in the United States. Crandall (1994) believed that a questionnaire

was needed to measure attitudes towards people with weight problems because

the United States obesity rate was the highest in the world (Baskin, Ard,

Franklin, & Allison, 2005) and there was a great deal of prejudice towards this

kind of people (Puhl et al., 2010).

The Antifat Attitudes Scale (AFA, Crandall, 1994) contained 13 items and

three subscales. The first factor, called dislike ( = .84), measured whether or not

people had negative feelings towards the overweight. The second subscale, called

fear of fat ( = .79), analysed to what extent the participants were afraid of gaining

weight. Finally, the third factor, called willpower ( = .66), measured whether or

not the subjects perceived that weight is controllable. It was found that men

scored higher on the dislike and willpower scales than women, and that women

scored higher on the fear of fat scale. Furthermore, to check the validity of the

questionnaire, Crandall (1994) administered it together with other questionnaires

that measured variables that were significantly related to prejudice towards other

less fortunate groups (such as authoritarianism, belief in a just world and political

conservatism) and found positive correlations with the different subscales of

the AFA.

The AFA scale has often been used in different kinds of studies (Dimmock,

Hallett, & Grove, 2009) and yielded sound results when measuring prejudice

towards the obese. However, in Spain there has been no Spanish-language

adaptation of the scale to date. For this reason, the goal of this article is to

validate a Spanish-language version of the AFA scale. To do so, we shall conduct

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

an exploratory analysis and a confirmatory analysis in a sample of Spanish

university students.

Therefore, through this study we aim to verify the factorial structure proposed

by Crandall (1994) and establish the psychometric criteria that will make it valid

so the Spanish-speaking scholarly community can use this instrument.

Method

Sample

The sample was made up of 1,457 participants with an average age of 27.5

(SD = 6.92) and an age range between 18 and 40. Of the total participants, 627

were males and 831 were females. All the participants were students at Spains

Universidad Nacional de Educacin a Distancia (National Distance Education

University, UNED). The people who were part of the sample had Body Mass

Indexes (BMIs) of between 18 and 25 (which the scientific community considers

normal weight). The participants with BMIs higher than 25 (overweight) or under

18 (underweight, eating behaviour problems) were eliminated from the sample.

All the subjects voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

Instrument

The Antifat Attitude Scale (AFA, Crandall, 1994) has been adapted to Spanish

using the translation/back-translation methodology as stipulated by many authors

(Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, & Ferraz, 2000) and the norms of the

International Test Commission (Hambleton & Bollwark, 1991). By using this

methodology, we can check the semantic and structural equivalency of the items

in the Spanish translation with those in the original questionnaire.

The first Spanish translation of the original scales was performed by one of the

authors. This Spanish translation was independently reviewed by an additional

evaluator, who worked with the main translator to reach an agreed-upon translation of the items, especially those which posed the most difficulty from the

semantic and/or grammatical standpoint. Subsequently, a bilingual English translator back-translated the agreed-upon Spanish-to-English translation with no

knowledge of the original scales in English in order to preserve the reliability of

the back-translation. The scale translated into English and the original scale

reached 100% grammatical agreement.

The AFA scale contains 13 items and is divided into three major groups of

questions (see Appendix). The first includes questions related to the feelings

aroused by overweight people in the participants (Example: I really dont like

fat people much). The second kind of question is related to the feelings

generated in the participants when they gain weight (Example: One of the

worst things that could happen to me would be if I gained 25 pounds).

Finally, the last section asks participants whether they perceive obesity as

controllable or not (Example: Fat people tend to be fat pretty much through

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

their own fault). The participants filled in a Likert scale ranging from 1

(strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Procedure

Information on the study was posted on the virtual courses taught by the

researchers in this study in order to request participation by anyone interested.

All volunteers who chose to participate in the study received class credit. The

students in the final sample had to download the questionnaire (the Escala de

Actitud Antiobesos) from the website and then send the completed questionnaire

by regular post to the main researcher of the study (along with other questionnaires which are irrelevant to this study). The participants had one month to

complete the questionnaire, after which it was no longer available. Because of the

circumstances of the university where the study was performed (UNED), data

were obtained from all the provinces in Spain.

Results

As mentioned at the end of the introduction, the prime objective of this study was

to analyse the factorial structure of the questionnaire. To verify the internal

structure of the AFA, an exploratory factorial analysis was performed (main

components, Varimax rotation) and then another confirmatory factorial analysis

was performed (maximum probability).

Due to the fact that we chose to perform these two kinds of analyses, we

decided to divide the sample into two, as recommended by the experts

(Petrowski, Paul, Albani, & Brhler, 2012). To do so, we used the SPSS

procedure to generate random samples which enabled the original sample to

be divided into two halves. After dividing the sample, we applied the exploratory factorial analysis to one half and the confirmatory factorial analysis to the

other. The purpose of this step is to check whether or not there is convergence

between the exploratory and confirmatory analyses. What is more, it is important to mention that the exploratory factorial analysis is a useful tool when it is

impossible to group the data yet there are plausible hypotheses regarding the

structure of a model, in which case the experts recommend the use of confirmatory factorial analysis as well (Bollen, 1989). For this reason, we chose to

work with both kinds of analyses.

To perform the exploratory factorial analysis, we used the SPSS programme.

For the confirmatory factorial analysis we used the AMOS programme (Arbuckle,

2011). To study the models fit, we did not use the Chi-squared test because it is

very sensitive to the sample size and is not advisable when there are more than

400 cases, as it is always significant. Instead, given the large amount of goodnessof-fit indexes available, we chose some that are well known and recommended,

such as the RMSEA (Residual Mean Squared Error Approximation Index), the

NFI (Normed Fit Index) and the CFI (Comparative Fit Index). Values lower than

.05 on the RMSEA and higher than .95 on the NFI and CFI indicate good fit

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

(Kline, 2011). The sample size was enough given that the relationship between the

number of subjects and the number of items was greater than 45:1 (Bentler &

Chou, 1987).

The second objective of the study was to analyse the psychometric properties

of the AFA scale. In this case, we decided to calculate the Cronbachs alphas (a

coefficient used to measure the reliability of a measurement scale) of both the

scale as a whole and the subscales (Cronbach & Shavelson, 2004).

Exploratory factorial analysis

First of all, we estimated the Cronbachs alpha of the complete scale (13

items). The overall reliability of the scale was .85. Even though the

Cronbachs alpha was so high (which indicates that all the items are measuring

the same thing), we chose to perform the exploratory factorial analysis to

check whether Crandalls original factorial structure (1994) could be

replicated.

Before performing the exploratory analysis, we performed a series of prior

calculations. First, we analysed whether our data matched a normal distribution.

To do so, we decided to measure the asymmetry (the normal distribution is

symmetrical if its asymmetry value is around 0) and kurtosis (measurement of the

degree of which the observations are grouped around a central point; for a normal

distribution, the statistical kurtosis value must be around 0) of the variables used in

the study. According to the analyses performed, we noted that the variables

analysed matched a normal distribution (values of between -1 and +1 for all 13

items on the scale). We then analysed the multicollinearity of the variables in our

study. Multicollinearity is said to exist among explanatory variables when there is

some kind of linear dependence or a strong correlation among them. To do this, it is

common to calculate Bartletts sphericity test and the Kaiser-Mayer-Olikin measure

of sampling adequacy (KMO). The sphericity test is interpreted as follows: if the

null hypothesis is accepted (p > .05) it means that the variables are not intercorrelated and therefore it does not make much sense to perform a factorial analysis

(Bartlett, 1950). In our case, the Chi-squared was 6595.66 (78 gl) with p < .01. For

the KMO measure, it is recommended that the value should fall between the range

of 0 and 1, but closer to 1 (Kaiser, 1970). In our case, the KMO value was .836,

which, according to the literature surveyed, is largely acceptable (Guttman, 1954).

Once these prior calculations had been performed (normality and multicollinearity),

we decided to perform the exploratory factorial analysis.

Once the prior checks had been completed, we chose to perform an exploratory factorial analysis using the maximum likelihood method (Kim & Mueller,

1978) with Varimax rotation (Kaiser, 1958). The main advantage of orthogonal

rotations (such as the Varimax rotation) is their simplicity, since the weights

represent the correlations between the factors and the variables. However, the

same does not hold true with oblique rotations.

Based on the main components analysis conducted with all 13 items on the

Antifat Attitudes Scale with a sample of 758 subjects, three components were

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

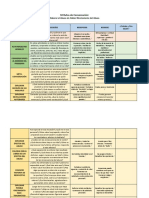

Table 1. Rotated component matrix.

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

afa1

afa2

afa3

afa4

afa5

afa6

afa7

afa8

afa9

afa10

afa11

afa12

afa13

Factor 1

Factor 2

Factor 3

.60

.44

.77

.71

.74

.79

.60

.02

.25

.02

.08

.04

.34

.11

.07

.01

.07

.03

.12

.21

.88

.79

.87

.17

.16

.11

.25

.20

.04

.03

.01

.11

.27

.17

.10

.20

.80

.82

.62

yielded in the final solution. These three factors were extracted with own values

higher than 1, as recommended by the experts (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996).

These three components explain 59.56% of the total variation, with saturations

as shown in Table 1.

The first component (dislike) explains 32.25% of the variation; it includes

items 17. The second component (fear of fat) explains 17.17% of the variation; it

includes items 810. The third component (willpower) explains 10.12% of the

variation; it includes items 1113. The structure found in the exploratory analysis

replicates the structure originally found by Crandall (1994).

It is important to mention that some authors (Van Groen, Klooster, Taal, Van

de Laar, & Glas, 2010) recommend that factors with fewer than four items (such

as fear of fat and willpower) not be identified as such. However, given that the

author of the original instrument (Crandall, 1994) designed the scale in this way,

we chose to respect this structure despite this methodological glitch.

Once the factors had been established via the exploratory analysis, we chose to

calculate the reliability of the three subscales. The Cronbachs alpha of subscale

A, dislike, was .86, for fear of fat it was .78 and for willpower it was .68.

Finally, we calculated the Pearson correlations among the different subscales

(Table 2). As shown in Table 2, positive, significant correlations were yielded in

the three factors found in the exploratory analysis.

Table 2. Correlations among AFA subscales.

Dislike

Fear

Willpower

Dislike

Fear

.33**

.38**

.36**

Willpower

Note: **The correlation is significant at the level of .01 (bilateral).

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Confirmatory factorial analysis

We performed a confirmatory factorial analysis on the other half of the

sample (759 subjects). As mentioned above, the reason we performed this

type of analysis was to check whether or not there was convergence with the

results of the exploratory analysis, and at the same time to follow the

recommendations of the exports, who advise performing a confirmatory

analysis when there are indications that there is a given factorial structure

(Bollen, 1989).

First, we calculated the Cronbachs alpha of the total scale (13 items), and

once again we got a fairly high score (.80). We chose to perform the factorial

analysis, in this case a confirmatory analysis, even though the result indicated that the items are probably measuring the same construct, since we

wanted to check whether Crandalls factorial structure (1994) matched our

data. To do this, we performed a confirmatory factorial analysis with three

factors: dislike (items 17), fear of fat (items 810) and willpower (items

1113).

Bearing in mind the goodness-of-fit indexes mentioned at the beginning of this

Results section, we cannot claim that the goodness-of-fit indexes were entirely

satisfactory (RMSEA = .08; NFI = .89; CFI = .90). However, it is important to

mention that according to Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (1998), values

under .05 for the RMSEA indicate acceptable fit, and values under .10 (as in

our case) indicate reasonable fit. Browne and Cudeck (1993) also postulate that a

fit less than or equal to .08 is reasonable.

In the case of the NFI index, Bentler and Bonett (1980) stipulated that

values equal to or higher than .90 indicate good fit, although other authors (Hu

& Bentler, 1999) are stricter and suggest that the value should be over .95. In

our case, we found an NFI of .89, which tells us that the fit is close to the

standard set by Bentler and Bonett (1980). This twofold criterion is also

applicable for the CFI index, which in our case was .90, which indicates

that based on the least stringent criterion of Bentler and Bonett (1980) this

may be considered acceptable fit.

The three-factor model with standardized coefficients (the relative weights of

each variable has a factor) are shown in Figure 1.

As can be seen, the confirmatory factorial analysis revealed the existence of a

three-factor structure (dislike, fear of fat and willpower). These three subscales are

positively related to each other. Once again we found that items 17 are part of the

first factor (dislike), items 810 the second factor (fear of fat) and the last three

items (1113) the third factor (willpower). As found in the exploratory factorial

analysis, we found a similar factorial structure to the one originally developed by

Crandall (1994). Therefore, we can posit convergence in the results with both

kinds of analysis.

Finally, once we had established the factors through the confirmatory analysis,

we chose to calculate the reliability of the three subscales. The Cronbachs alpha

of the dislike subscale was .70, of the fear of fat scale it was .85 and of the

willpower scale it was .72.

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

E1

AFA1

E2

AFA2

E3

AFA3

.57

.28

E4

.68

Dislike

.62

AFA4

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

.63

E5

AFA5

E6

AFA6

E7

AFA7

E8

AFA8

E9

AFA9

.79

.63

.24

.85

.32

Fear of fat

.68

.45

.87

E10

AFA10

E11

AFA11

.68

E12

E13

AFA12

AFA13

.80

Willpower

.57

Figure 1. Three-factor model related to the standardized coefficients ().

Taken as a whole, these results show that the Antifat Attitudes Scale has three

clearly defined subscales, and that there is a positive relationship between the

different factors of the instrument, as shown by the results of both the exploratory

and the confirmatory factorial analyses.

Gender differences

Finally, we performed three analyses of variance (ANOVA) with the total sample

(1,457 participants) to check whether there were any gender differences in the

AFAs subscales, as Crandall (1994) originally found. As can be seen in Table 3,

males scored higher on the dislike subscale (F(1, 1455) = 35.67, p < .01), while

females scored higher on the fear of fat (F(1, 1455) = 75.34, p < .01) and

willpower (F(1, 1455) = 60.54, p < .01) subscales.

10

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Table 3. Descriptions of the AFA scale for males and females.

Males

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Females

Dislike

Fear

Willpower

Dislike

Fear

Willpower

Mean

Standard deviation

Sample size

1.96

2.73

3.35

1.73

3.39

3.83

0.74

0.96

0.79

0.75

1.72

1.39

627

831

Discussion

This article reveals that the Antifat Attitudes Scale (AFA,) is a questionnaire that

can be used in the Spanish-speaking community to measure prejudice towards

people with weight problems. Judging from the results, this scale has a factorial

structure of three subscales (dislike, fear of fat and willpower), as shown by both

the exploratory and the confirmatory factorial analyses. Likewise, the reliability of

both the total scale and the subscales is appropriate given the Cronbachs alphas

found (Cronbach & Shavelson, 2004). What is more, we found that the different

subscales are positively related to each other, as shown by the analyses performed.

Therefore, given these results, both of the goals of this study, namely to

replicate the factorial structure of Crandalls questionnaire (1994) and to analyse

the psychometric properties of the scale, were fulfilled. We believe that based on

the information presented in the preceding sections, the AFA questionnaire can be

safely used to measure antifat attitudes.

As mentioned in the introduction, it is important to stress that the AFA scale

(Crandall, 1994) is not the only scale used to measure antifat attitudes. For

example, there are open-ended questionnaires that measure attitudes towards

obese people (Allison et al., 1991; Bacon et al., 2001; Lewis et al., 1997;

Morrison & OConnor, 1999) as well as implicit measurements (Teachman &

Brownell, 2001). Both kinds of tools have been proven to be effective in measuring negative attitudes towards obese people. However, we believe that the scale

presented in this study is a valuable instrument for measuring prejudice towards

obese people, as revealed throughout this article, although we also believe that it

is important for professionals to be aware of other instruments and for them to

choose the tool they deem the most useful.

Additionally, based on our results we can state that males score higher on the

dislike subscale, while women score higher on the fear of fat and willpower

subscales. In Crandalls original study (1994), males scored higher on willpower,

and this finding has been replicated in other more recent studies (Magallares &

Morales, 2013). This is an unexpected result given that the perception of weight

control is related to the prejudice shown towards the obese, as our correlations

show and as suggested recently by other authors (OBrien, Latner, Ebneter, &

Hunter, 2013). Therefore, we can say that even though females score higher on

willpower (that is, they perceive obesity as controllable), this does not translate

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

11

into greater prejudice towards obese people. This may be related to the fact that

women internalize the societal norm of thinness, that is, that they apply this

standard of the controllability of weight to themselves more than they externalize

it by expressing negative attitudes towards people with weight problems

(Magallares & Morales, 2013).

On the other hand, future studies can address the validity of the construct and

analyse what other variables are related to the expression of prejudice towards the

obese. A survey of the literature suggests that there are other variables (such as

sexism and authoritarianism, just to cite two of them) which are related to

negative attitudes towards overweight people (Ebneter, Latner, & OBrien, 2011).

This study has two limitations. First, the sample is made up of university

students. We believe that it would have been worthwhile to use participants form

other social strata or with lower educational levels in order to make the sample as

heterogeneous as possible. Secondly, as mentioned above, people with BMIs

under 18 or higher than 25 were eliminated from the final sample. On future

occasions, it might be interesting to analyse the scores of participants with higher

body weights because, as the research has shown, obese people themselves show

prejudices towards members of their own group (Crandall, 1994).

Despite these limitations, this study clearly shows that the Antifat Attitudes

Scale is a valid, appropriate tool for measuring prejudice towards obese people

which will be useful for all researchers in the Spanish-speaking world who are

interested in studying prejudice towards people with weight problems.

12

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Adaptacin al castellano de la Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

La obesidad se define como una acumulacin excesiva de tejido adiposo que se

traduce en un aumento del peso corporal (World Health Organization, 2000). La

causa ms frecuente de esta enfermedad es la exgena o nutricional, aunque

conviene resear que tambin puede ser la consecuencia de determinadas enfermedades endocrinas (hipotiroidismo, sndrome de Cushing, hipogonadismo primario o sndrome del ovario poliqustico), sndromes genticos (Laurence Monn

Bielde, Alstrom o Prader Willi) o lesiones hipotalmicas (Haslam y James, 2005).

Adems, es importante recalcar que la obesidad est asociada a diversas enfermedades (lo que se conoce como comorbilidades) como las dislipemias, la diabetes

tipo 2, la hipertensin arterial, la artropata degenerativa o el sndrome de apnea

del sueo (Guh et al., 2009).

La prevalencia de la obesidad en los pases occidentales es realmente

elevada (King, 2011). En el caso espaol, los ltimos estudios ponen de

manifiesto que la prevalencia de sobrepeso en la poblacin es del 34,2% y

la de obesidad del 13,6% (Rodrguez-Rodrguez, Lpez-Plaza, Lpez-Sobaler,

y Ortega, 2011). Analizando los primeros estudios que se hicieron al respecto

en Espaa (Aranceta et al., 1998) y los ltimos trabajos, se constata un

incremento llamativo del nmero de personas obesas (Basterra-Gortari et al.,

2011), lo que da una idea de la magnitud que est alcanzando este problema.

Por lo tanto, la obesidad, un problema mdico en origen, se ha acabado

convirtiendo con el paso del tiempo tambin en un problema social en la

medida en que cada vez afecta a ms capas de poblacin. Por ello, parece

especialmente relevante tener en cuenta cmo las personas se comportan con

los obesos, ya que algunos estudios revelan que las personas de este colectivo

se encuentran socialmente estigmatizadas (Puhl y Heuer, 2009).

Discriminacin a las personas obesas

La literatura cientfica analizada pone de manifiesto que las personas obesas

sufren discriminacin en muchas reas sociales (Puhl, Heuer, y Brownell,

2010). En el rea de la salud se observa que los profesionales sanitarios comparten

una serie de creencias negativas sobre los obesos (suelen considerar a sus

pacientes obesos como vagos y poco inteligentes, muy en la lnea del estereotipo

social predominante) lo que acaba repercutiendo en el tratamiento que reciben los

pacientes con problemas de peso (Huizinga, Bleich, Beach, Clark, y Cooper,

2010). En el mbito laboral tambin existe un estereotipo tan negativo del

trabajador obeso (se cree que son ms lentos y torpes que el resto de personas)

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

13

que es prcticamente imposible que la gente con sobrepeso pueda competir en

igualdad de condiciones con el resto de personas en el mercado laboral

(Agerstrm y Rooth, 2011). En general se ha hallado que las personas obesas

tienen problemas en los procesos de seleccin de personal, obtienen una menor

remuneracin econmica, ocupan puestos de inferior categora y sufren una mayor

tasa de paro. Investigaciones en el rea educativa tambin encuentran que el

prejuicio hacia los nios y nias con sobrepeso estn muy extendidos (Turnbull,

Heaslip, y McLeod, 2000). En el rea de las relaciones interpersonales, con

resultados igualmente similares, se ha encontrado que las personas de este colectivo reciben un trato ms negativo que la gente con un menor peso corporal

(Hersch 2011). Por ltimo, la imagen que se da de las personas obesas en los

medios de comunicacin es, en muchas ocasiones, negativa, y ello contribuye a

diseminar entre la poblacin los estereotipos acerca de las personas con sobrepeso

(McClure, Puhl, y Heuer, 2011). Es importante recalcar que muchas de las

investigaciones reseadas se han realizado en contextos anglosajones, aunque en

Espaa tambin existen estudios sobre la existencia de prejuicio hacia las personas

obesas en muchas de las reas sociales mencionadas (Juregui-Lobera, RivasFernndez, Montaa-Gonzlez, y Morales-Milln, 2008).

Es especialmente relevante mencionar que son muchos los trabajos que

relacionan la discriminacin que sufren los obesos con el descenso en la

calidad de vida de las personas con sobrepeso (Ashmore, Friedman,

Reichmann, y Musante, 2008). Por todo ello, desde la Psicologia Social se

ha considerado oportuno estudiar el prejuicio hacia las personas obesas

(Crandall, 1994). Para analizar las valoraciones que se realizan de las personas

con problemas de peso se han desarrollado una serie de cuestionarios, entre los

cuales destaca la Antifat Attitudes Scale (Crandall, 1994).

Escalas de Actitud Antiobesos

En la actualidad existen muchos instrumentos disponibles en la comunidad

cientfica para medir actitudes antiobesos. Sin nimo de ser exhaustivos,

podemos mencionar la Beliefs About Obese Persons Scale (BAOP, Allison,

Basile, y Yuker, 1991), la Attitudes Toward Obese Persons Scale (ATOP,

Allison et al., 1991), la Anti-fat Attitudes Scale (AFAS, Morrison y

OConnor, 1999), el Anti-fat Attitudes Test (AFAT, Lewis, Cash, & BubbLewis, 1997) y la Fat Phobia Scale (Bacon, Scheltema y Robinson, 2001).

Sin embargo, la ms utilizada es la Antifat Attitudes Scale (AFA, Crandall,

1994).

En 1994, Christian Crandall desarroll una escala para medir el prejuicio

hacia las personas obesas en los Estados Unidos. Crandall (1994) estim

oportuno crear este cuestionario para medir las actitudes hacia las personas

con problemas de peso porque en los Estados Unidos las tasas de prevalencia

eran una de las ms elevadas del mundo (Baskin, Ard, Franklin, y Allison,

2005) y exista un gran prejuicio hacia este tipo de personas (Puhl et al.,

2010).

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

14

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

La Antifat Attitudes Scale (AFA, Crandall, 1994) constaba de 13 tems y

contena tres sub-escalas. El primer factor denominado Antipata ( = .84),

meda si las personas tenan sentimientos negativos hacia las personas con

problemas de peso o no. La segunda sub-escala, llamado Miedo a la Gordura

( = .79), analizaba en qu medida los participantes tenan miedo a coger peso.

Por ltimo, un tercer factor, denominado Voluntad ( = .66), meda si los sujetos

perciban que el peso de las personas era controlable o no. En el cuestionario se

observaba que los hombres puntuaban ms alto en la escala de Antipata y

Voluntad mientras que las mujeres lo hacan en el factor de Miedo a la

Gordura. Adems, Crandall (1994) para comprobar la validez del cuestionario

pas esta escala junto con otros cuestionarios que medan variables que se

relacionaban de forma significativa con el prejuicio hacia otros colectivos desfavorecidos (por ejemplo, autoritarismo, creencia en un mundo justo o conservadurismo poltico), encontrando correlaciones positivas con las diferentes sub-escalas

de la AFA.

La escala AFA se ha usado en muchas ocasiones en diferentes tipos de

investigaciones (Dimmock, Hallett, y Grove, 2009) dando buenos resultados

para medir prejuicio hacia las personas obesas. Sin embargo, en Espaa,

hasta la fecha, no existe una adaptacin al castellano de esta escala. Por

ello, el objetivo del presente artculo es validar una versin castellana de la

escala AFA. Para ello, se harn un anlisis exploratorio y un confirmatorio

para comprobar si la estructura de la escala original propuesta por Crandall

(1994) se mantiene en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios espaoles.

Por lo tanto, con la realizacin de este estudio se pretende verificar la

estructura factorial propuesta por Crandall (1994) y establecer los criterios

psicomtricos que la habilitaran para que la comunidad cientfica hispanohablante pudiera usar este instrumento.

Mtodo

Muestra

La muestra estuvo compuesta por 1.457 participantes con una media de edad de

27.5 aos (DT = 6.92) y con un rango de edad entre 18 y 40 aos. Del total de

participantes, 627 eran hombres y 831 mujeres. Todos los participantes eran

estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional de Educacin a Distancia (UNED). Las

personas que forman parte de la muestra final tenan ndices de Masa Corporal

(IMC) entre 18 y 25 (lo que la comunidad cientfica establece como normopeso).

Los participantes con IMCs superiores a 25 (sobrepeso) o inferiores a 18 (problemas de la conducta alimentaria) fueron eliminados de la muestra. Todos los

sujetos accedieron a participar voluntariamente en la investigacin.

Instrumento

La Escala de Actitudes Antiobesos (AFA, Crandall, 1994) ha sido adaptada al

castellano mediante la metodologa traduccin-retrotraduccin segn lo estipulado

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

15

por algunos autores (Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, y Ferraz, 2000) y las normas

de la International Test Comission (Hambleton y Bollwark, 1991). Mediante esta

metodologa se puede comprobar la equivalencia semntica y estructural entre los

tems de la traduccin al castellano y los originales.

La primera traduccin al castellano de las escalas originales fue realizada por

uno de los autores. Esta traduccin al castellano fue revisada independientemente por otro evaluador adicional, que junto con el traductor principal, acordaron una traduccin consensuada de los tems, en especial de aquellos que ms

dificultad planteaban desde un punto de vista semntico y/o gramatical.

Posteriormente, una traductora inglesa bilinge llev a cabo la retrotraduccin

de la traduccin consensuada del castellano al ingls, desconociendo sta las

escalas originales en ingls para preservar la fiabilidad de la retrotraduccin. La

escala traducida al ingls y la original obtuvieron una coincidencia gramatical

del 100%.

La escala AFA contiene 13 tems y se divide en tres grandes bloques de

preguntas (ver Apndice). En el primero de ellos se incluyen cuestiones relativas

a los sentimientos que suscitan las personas con sobrepeso en los participantes

(Ejemplo: No me gusta mucho la gente gorda). Un segundo tipo de preguntas

versa, en este caso, sobre las sensaciones que genera en los participantes el hecho

de ganar peso (Ejemplo: Una de las peores cosas que me podran pasar es que

ganara unos kilos de peso). Por ltimo, existe una seccin donde se pregunta a

los participantes si perciben que la obesidad es algo controlable o no (Ejemplo:

La gente gorda tiene ese peso principalmente por su propia culpa). Los participantes rellenaban una escala tipo Likert que iba de 1 (nada de acuerdo) a 7

(completamente de acuerdo).

Procedimiento

Se coloc informacin relativa a la realizacin de un estudio en los cursos

virtuales de la asignatura de la que forman parte los investigadores del presente

estudio para pedir colaboradores que quisieran participar. Todos aquellos voluntarios que optaron por formar parte del estudio recibieron crditos en la asignatura. Los alumnos que formaron parte de la muestra final deban descargarse el

cuestionario (la Escala de Actitud Antiobesos) de la citada pgina web y posteriormente mandar por correo ordinario al investigador principal del estudio el

cuestionario rellenado (junto con otros cuestionarios no relevantes para el presente

estudio). Los participantes disponan de un mes para la realizacin de la tarea,

fecha a partir de la cual dejaba de estar disponible el cuestionario. Por la

idiosincrasia de la Universidad donde se ha realizado el presente estudio

(UNED) se obtuvieron datos de todas las provincias de la geografa espaola.

Resultados

Como se coment en la parte de final de la introduccin, el primer objetivo del

estudio era analizar la estructura factorial del cuestionario. Para verificar la

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

16

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

estructura interna de la AFA, se realiz un anlisis factorial exploratorio

(Componentes Principales, rotacin Varimax) y otro confirmatorio (Mxima

Probabilidad).

Debido a que se opt por realizar estos dos tipos de anlisis se decidi

dividir la muestra en dos, tal y como recomiendan los expertos (Petrowski, Paul,

Albani, y Brhler, 2012). Para ello, se utiliz el procedimiento de SPSS para

generar muestras aleatorias, que permiti que la muestra original fuera dividida

en dos mitades. Despus de dividir la muestra, se aplic el anlisis factorial

exploratorio en una mitad y la segunda mitad de la muestra fue utilizada para

realizar el anlisis factorial confirmatorio. El objetivo de este paso es comprobar

si existe convergencia o no entre el anlisis exploratorio y el confirmatorio.

Adems, es importante mencionar que el anlisis factorial exploratorio es una

herramienta til en reas en las que no se conoce la posible agrupacin de los

datos pero cuando existen hiptesis plausibles sobre la estructura de un modelo,

como es el caso, los expertos aconsejan tambin el uso del anlisis factorial

confirmatorio (Bollen, 1989). Por esta razn, se opt por trabajar con ambos

tipos de anlisis.

Para realizar el anlisis factorial exploratorio se utiliz el programa SPSS.

Para el anlisis factorial confirmatorio se emple el programa AMOS

(Arbuckle, 2011). Para el estudio de los ajustes de los modelos no se us el

test de 2, dado que es muy sensible al tamao de la muestra y no es

aconsejable cuando el nmero de casos es mayor de 400, pues siempre resulta

significativa. Por ello, entre la gran cantidad de ndices de ajuste existentes,

elegimos algunos que son bien conocidos y recomendados, como el RMSEA

(Residual Mean Squared Error Approximation Index), el NFI (Normed Fit

Index) y el CFI (Comparative Fit Index). Los valores menores de .05 en el

caso del RMSEA, y superiores a .95 en el caso del NFI y CFI indican un buen

ajuste (Kline, 2011). El tamao muestral fue suficiente dado que la relacin

entre el nmero de sujetos y el nmero de tems fue mayor que 45:1 (Bentler y

Chou, 1987).

El segundo de los objetivos del estudio era analizar las propiedades

psicomtricas de la escala AFA. En este caso se opt por calcular los alphas de

Cronbach (coeficiente que sirve para medir la fiabilidad de una escala de medida)

de la escala y de las sub-escalas (Cronbach y Shavelson, 2004).

Anlisis factorial exploratorio

En primer lugar se estim el coeficiente Alfa de Cronbach de la escala al completo

(13 tems). La fiabilidad de la escala total fue .85. A pesar de tener un alfa tan

elevado (que indica que todos los tems estn midiendo lo mismo) se opt por

realizar el anlisis factorial exploratorio para comprobar si se puede replicar o no

la estructura factorial original de Crandall (1994).

Antes de realizar el anlisis exploratorio se realizaron una serie de clculos

previos. En primer lugar, se analiz si nuestros datos se ajustaban a una

distribucin normal. Para ello se decidi medir la asimetra (la distribucin

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

17

normal es simtrica si tiene un valor de asimetra en torno a 0) y la curtosis

(medida del grado en que las observaciones estn agrupadas en torno al punto

central. Para una distribucin normal, el valor del estadstico de curtosis debe

estar en torno a 0) de las variables utilizadas en el estudio. De acuerdo a los

anlisis realizados se comprob que las variables analizadas se ajustaban a una

distribucin normal (valores comprendidos entre -1 y +1 para los 13 tems de

la escala). A continuacin, se analiz la multicolinealidad de las variables de

nuestro estudio. Se dice que existe multicolinealidad entre las variables explicativas cuando hay algn tipo de dependencia lineal entre ellas, o lo que es lo

mismo, si existe una fuerte correlacin entre las mismas. Para ello se suele

calcular el test de esfericidad de Bartlett y la medida de adecuacin muestral

de Kaiser-Mayer-Olikin (KMO). El test de esfericidad se interpreta de la

siguiente manera: si se acepta la hiptesis nula (p > .05) significa que las

variables no estn intercorrelacionadas y por tanto no tiene mucho sentido

llevar a cabo un Anlisis Factorial (Bartlett, 1950). En nuestro caso obtuvimos

una 2 de 6595.66 (78 gl) y con una p < .01. En el caso del KMO se

recomienda que el valor se encuentre entre el rango 0 y 1, pero ms cercano

a la unidad (Kaiser, 1970). En nuestro caso obtuvimos un valor de KMO .836

que, segn la literatura revisada, es bastante aceptable (Guttman, 1954). Una

vez realizados estos clculos previos (normalidad y multicolinealidad) se

decidi realizar el anlisis factorial exploratorio.

Una vez hechas estas comprobaciones, se opt por realizar un anlisis

factorial exploratorio con el Mtodo de Mxima Verosimilitud (Kim y

Mueller, 1978) y con una rotacin Varimax (Kaiser, 1958). La ventaja principal de las rotaciones ortogonales (como es la rotacin Varimax) es su simplicidad, ya que los pesos representan las correlaciones entre los factores y las

variables. Sin embargo esto no se cumple en el caso de las rotaciones

oblicuas.

A partir del anlisis de componentes principales llevado a cabo con los 13

tems de la Escala de Actitudes Antiobesos con una muestra de 758 sujetos se

obtuvieron tres componentes en la solucin final. Estos tres factores fueron

extrados con valores propios superiores a 1 tal y como recomiendan los expertos

(Tabachnick y Fidell, 1996).

Los tres componentes explican el 59.56% de la varianza total, con unas

saturaciones que pueden verse en la Tabla 1.

El primer componente (Antipata), explica el 32.25% de la varianza. Incluye

los tems, del 1 al 7. El segundo componente (Miedo a la Gordura), explica el

17.17% de la varianza. Est formado por los tems 8, 9 y 10. El tercer componente

(Voluntad), explica el 10.12% de la varianza. Est formado por los tems 11, 12 y

13. La estructura encontrada en este anlisis exploratorio es una rplica de la

hallada originalmente por Crandall (1994).

Es importante mencionar que algunos autores (Van Groen, Klooster, Taal, Van

de Laar y Glas, 2010) recomiendan que no se identifiquen como factores aquellos

que posean menos de cuatro tems (como en el caso de los factores de Miedo a la

Gordura y Voluntad). Ahora bien, dado que el autor del instrumento original

18

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Tabla 1.

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

afa1

afa2

afa3

afa4

afa5

afa6

afa7

afa8

afa9

afa10

afa11

afa12

afa13

Matriz de componentes rotados.

Factor 1

Factor 2

Factor 3

.60

.44

.77

.71

.74

.79

.60

.02

.25

.02

.08

.04

.34

.11

.07

.01

.07

.03

.12

.21

.88

.79

.87

.17

.16

.11

.25

.20

.04

.03

.01

.11

.27

.17

.10

.20

.80

.82

.62

(Crandall, 1994) dise de esta manera la escala, optamos por respetar esa

estructura, a pesar de la citada inconveniencia metodolgica.

Una vez establecidos los factores mediante el anlisis exploratorio se opt por

calcular la fiabilidad de los tres sub-escalas halladas. El Alfa de Cronbach de la

sub-escala Antipata fue .86, la de Miedo a la Gordura de .78 y la de Voluntad

de .68.

Por ltimo, se calcularon las correlaciones de Pearson entre las diferentes subescalas (Tabla 2). Como se puede observar, se hallaron correlaciones positivas y

significativas entre los tres factores hallados en el anlisis exploratorio.

Anlisis factorial confirmatorio

Con la otra mitad de la muestra (759 sujetos) se realiz un anlisis factorial

confirmatorio. Como ya se coment, el objetivo de realizar este tipo de anlisis

era comprobar si exista convergencia o no con lo obtenido en el exploratorio y, al

mismo tiempo, seguir las recomendaciones de los expertos que aconsejan hacer un

anlisis confirmatorio cuando existen indicios de que existe una estructura factorial determinada (Bollen, 1989).

Tabla 2.

Antipata

Miedo

Voluntad

Correlaciones entre las sub-escalas de AFA.

Antipata

Miedo

.33**

.38**

.36**

Nota: **La correlacin es significativa al nivel .01 (bilateral)

Voluntad

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

19

En primer lugar, se calcul el alpha de Cronbach de la escala total (13

tems). De nuevo se obtuvo un valor bastante elevado (.80). Se opt por

realizar el anlisis factorial, en este caso confirmatorio, a pesar de que este

resultado indique que los tems pueden estar midiendo el mismo constructo,

ya que se quera comprobar si la estructura factorial de Crandall (1994) se

ajustaba a nuestros datos. Para ello, se realiz un anlisis factorial confirmatorio, con tres factores: Antipata (tems del 1 al 7), Miedo a la Gordura

(tems del 8 al 10) y Voluntad (tems del 11 al 13).

Teniendo en cuenta los ndices de ajuste comentados al principio de esta

seccin de Resultados, no se podra decir que los ndices de ajuste que se

obtuvieron sean enteramente satisfactorios (RMSEA = .08; NFI = .89;

CFI = .90). Sin embargo, es importante mencionar que segn Hair, Anderson,

Tatham y Black (1998) los valores inferiores a .05 para el RMSEA indican un

buen ajuste y valores inferiores a .10 (como es nuestro caso) un ajuste razonable.

Browne y Cudeck (1993) tambin postulan que un ajuste menor o igual a .08 es

razonable.

En el caso del ndice NFI, Bentler y Bonnet (1980) establecen que valores

iguales o superiores a .90 indican un buen ajuste, aunque algunos otros

autores (Hu y Bentler, 1999) son ms estrictos y postulan que el valor

debe estar por encima de .95. En nuestro caso, hallamos un NFI de .89 lo

cual nos indica que el ajuste se acerca al standard de Bentler y Bonnet

(1980). Este doble criterio es tambin aplicable para el ndice CFI, que, en

nuestro caso, fue de .90, lo cual indica que desde el criterio menos

exigente de Bentler y Bonnet (1980) podramos estar hablando de un ajuste

aceptable.

El modelo de tres factores relacionados, con los coeficientes estandarizados

(los pesos relativos que cada variable tiene en el factor), se muestra en la

Figura 1.

Como se puede ver, el anlisis factorial confirmatorio pone de manifiesto la

existencia de una estructura de tres factores (Antipata, Miedo a la Gordura y

Voluntad). Estas tres sub-escalas se encuentran positivamente relacionadas

entre ellas. De nuevo hallamos que los tems del 1 al 7 forman parte del

primer factor (Antipata), los tems del 8 al 10 parte del segundo (Miedo a la

Gordura) y los tres ltimos (11 al 13) parte del tercer factor (Voluntad). Tal y

como se encontr con el anlisis factorial exploratorio, hallamos una estructura

factorial similar a la desarrollada originalmente por Crandall (1994). Por lo

tanto, podemos hablar de convergencia en los resultados con ambos tipos de

anlisis.

Por ltimo, una vez establecidos los factores mediante el anlisis confirmatorio

se opt por calcular la fiabilidad de los tres sub-escalas. El Alfa de Cronbach de la

sub-escala Antipata fue .70, la de Miedo a la Gordura de .85 y la de Voluntad

de .72.

Tomados en su conjunto, estos resultados ponen de manifiesto que la Escala de

Actitudes Antiobesos presenta tres sub-escalas claramente definidas, existiendo

una relacin positiva entre los diferentes factores del instrumento, tal y como

20

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

E1

AFA1

E2

AFA2

E3

AFA3

.57

.28

E4

.68

Antipata

.62

AFA4

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

.63

E5

AFA5

E6

AFA6

E7

AFA7

E8

AFA8

E9

AFA9

.79

.63

.24

Miedo a la

Gordura

.85

.68

.32

.45

.87

E10

AFA10

E11

AFA11

.68

E12

E13

AFA12

AFA13

.80

Voluntad

.57

Figura 1. Modelo de tres factores relacionados con los coeficientes estandarizados ().

muestran los resultados tanto del anlisis factorial exploratorio como del anlisis

factorial confirmatorio.

Diferencias de gnero

Por ltimo, con el total de la muestra (1.457 participantes) se realizaron tres

anlisis de varianza (ANOVA) para comprobar si existan diferencias en funcin

del gnero en las sub-escalas del AFA tal y como hall originalmente Crandall

(1994). Como puede observarse en la Tabla 3, los hombres puntan ms alto en la

sub-escala de Antipata (F(1, 1455) = 35.67, p < .01) mientras que las mujeres lo

hacen en la de Miedo a la Gordura (F(1, 1455) = 75.34, p < .01) y Voluntad (F(1,

1455) = 60.54, p < .01).

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

Tabla 3.

Hombres

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Mujeres

21

Descriptivos de la escala AFA para hombres y mujeres.

Antipata

Miedo

Voluntad

Antipata

Miedo

Voluntad

Media

Desviacin tpica

Tamao muestral

1.96

2.73

3.35

1.73

3.39

3.83

0.74

0.96

0.79

0.75

1.72

1.39

627

831

Discusin

El presente artculo pone de manifiesto que la Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

(AFA, Crandall, 1994) es un cuestionario que puede ser usado en la comunidad hispanohablante para medir el prejuicio hacia las personas con problemas de peso. A tenor de los resultados obtenidos, esta escala tiene una

estructura factorial de tres sub-escalas (Antipata, Miedo a la Gordura y

Voluntad), tal y como han puesto de manifiesto tanto el anlisis factorial

exploratorio como el confirmatorio, y al mismo tiempo que la fiabilidad de la

escala total como la de las sub-escalas es la adecuada, atendiendo a los

alphas de Cronbach encontrados (Cronbach y Shavelson, 2004). Adems,

se ha hallado que las diferentes sub-escalas se encuentran positivamente

relacionadas las unas con las otras tal y como han mostrado los anlisis

realizados.

Por lo tanto, los dos objetivos que se perseguan, replicar la estructura factorial

del cuestionario de Crandall (1994) y analizar las propiedades psicomtricas de la

escala, han sido cumplidos a tenor de los resultados obtenidos. Creemos que en

funcin de lo expuesto en las secciones precedentes, el cuestionario AFA puede

ser utilizado con garanta para medir actitudes antiobesos.

Es importante recalcar que la escala AFA (Crandall, 1994), tal y como se

ha comentado en la seccin introductoria, no es la nica que existe para medir

actitudes antiobesos. Por ejemplo, existen cuestionarios abiertos para medir

actitudes hacia las personas obesas (Allison et al., 1991; Bacon et al., 2001;

Lewis et al., 1997; Morrison y OConnor, 1999) y tambin medidas implcitas

(Teachman y Brownell, 2001). Ambos tipos de herramientas han demostrado

ser eficaces para medir actitudes negativas hacia las personas obesas. En

cualquier caso, creemos que la escala presentada en este trabajo es un instrumento muy valioso para medir el prejuicio hacia las personas obesas, tal y

como hemos dejado de manifiesto a lo largo del manuscrito, aunque creemos

que es importante que se conozcan tambin otros instrumentos y que los

profesionales que quieran medir actitudes antiobesos elijan aquella herramienta

que consideren ms til.

Adicionalmente, podemos decir, en funcin de nuestros resultados, que

los hombres puntan ms alto en la sub-escala de Antipata mientras que las

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

22

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

mujeres lo hacen en las de Miedo a la Gordura y Voluntad. En el estudio

original de Crandall (1994), los hombres puntuaban ms alto en la escala de

Voluntad al igual que en otros trabajos ms recientes (Magallares y Morales,

2013). Es un resultado inesperado puesto que la percepcin de control del

peso se relaciona con el prejuicio que se muestra hacia las personas obesas,

tal y como nuestras correlaciones muestran y como han sugerido algunos

autores recientemente (OBrien, Latner, Ebneter, y Hunter, 2013). Por lo

tanto, podemos decir que aunque las mujeres puntan ms alto en Voluntad

(es decir, perciben la obesidad como algo ms controlable) esto no se traduce

en un mayor prejuicio hacia las personas obesas, lo cual puede estar relacionado con el hecho de que las mujeres interiorizan la norma social de

delgadez, es decir, que se aplican a ellas mismas ese standard acerca de la

controlabilidad del peso ms que externalizarlo a travs de la expresin de

actitudes negativas hacia las personas con problemas de peso (Magallares y

Morales, 2013).

Por otra parte, en futuros trabajos debera abordarse tambin el estudio de la

validez de constructo y analizar qu otras variables se relacionan con la expresin

del prejuicio hacia las personas obesas. La revisin de la literatura sugiere que hay

otras variables (como el sexismo, el autoritarismo por citar dos de ellas) que se

relacionan con las actitudes negativas hacia las personas con sobrepeso (Ebneter,

Latner, y OBrien, 2011).

Como limitaciones del presente trabajo podemos mencionar al menos dos.

En primer lugar, se trata de una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. Creemos

que hubiera sido interesante poder acceder a participantes de otros estratos

sociales o con un menor nivel educativo, de cara a que la muestra fuera lo ms

heterognea posible. En segundo lugar, como se ha comentado, las personas

con IMCs corporales inferiores a 18 o superiores a 25 fueron eliminados de la

muestra final. Para futuras ocasiones sera interesante analizar las puntuaciones

de los participantes con pesos corporales ms elevados porque tal y como ha

puesto de manifiesto la investigacin se ha encontrado que las propias personas obesas muestran prejuicios hacia los miembros de su propio grupo

(Crandall, 1994).

A pesar de estas limitaciones, el presente estudio muestra claramente que la Escala

de Actitud Antiobesos es una herramienta vlida y adecuada para la medida del

prejuicio hacia las personas obesas, lo que ser til para todos aquellos investigadores

del mbito hispanohablante que estn interesados en estudiar el prejuicio hacia las

personas con problemas de peso.

References / Referencias

Agerstrm, J., & Rooth, D. (2011). The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring

discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 790805. doi:10.1037/a0021594

Allison, D. B., Basile, V. C., & Yuker, Y. E. (1991). The measurement of attitudes toward

and beliefs about obese persons. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10,

599607.

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

23

Aranceta, J., Prez Rodrigo, C., Serra Majem, L., Ribas, L., & Quiles Izquierdo, J.,

Grupo Colaborativo Espaol para el Estudio de la Obesidad. (1998). Prevalencia de la

obesidad en Espaa: estudio SEEDO97. Medicina Clnica, 111, 441445.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2011). AMOS: A Structural Equations Modeling Program (Versin 20.0)

[Programa]. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Ashmore, J., Friedman, K., Reichmann, S., & Musante, G. (2008). Weight-based stigmatization, psychological distress, & binge eating behavior among obese treatmentseeking adults. Eating Behaviors, 9, 203209. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.09.006

Bacon, J. G., Scheltema, K. E., & Robinson, B. E. (2001). Fat phobia scale revisited: The

short form. International Journal of Obesity, 25, 252257. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801537

Bartlett, M. S. (1950). Tests of significance in factor analysis. British Journal of

Psychology, 3, 7785.

Baskin, M., Ard, J., & Franklin, F., Allison, D B. (2005). Prevalence of obesity in the

United States. Obesity Reviews, 6, 57. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00165.x

Basterra-Gortari, F., Beunza, J., BesRastrollo, M., Toledo, E., GarcaLpez, M., &

MartnezGonzlez, M. (2011). Tendencia creciente de la prevalencia de obesidad

mrbida en Espaa: de 1,8 a 6,1 por mil en 14 aos. Revista Espaola de Cardiologa,

64, 424426. doi:10.1016/j.recesp.2010.06.010

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the

process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25, 31863191.

doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Bentler, P., & Bonett, D. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of

covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588606. doi:10.1037/00332909.88.3.588

Bentler, P., & Chou, C. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological

Methods & Research, 16, 78117. doi:10.1177/0049124187016001004

Bollen, K. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R.. 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K.

Bollen & J. Long (Eds.). Testing structural equation models (pp. 136162). Beverly

Hills, CA: Sage.

Crandall, C. S. (1994). Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-Interest. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 882894. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.882

Cronbach, L., & Shavelson, R. (2004). My current thoughts on coefficient alpha and

successor procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64, 391418.

doi:10.1177/0013164404266386

Dimmock, J. A., Hallett, B. E., & Grove, J. R. (2009). Attitudes toward overweight

individuals among fitness center employees: An examination of contextual effects.

Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 80, 641647.

Ebneter, D., Latner, J., & OBrien, K. (2011). Just world beliefs, causal beliefs, and acquaintance: Associations with stigma toward eating disorders and obesity. Personality &

Individual Differences, 51, 618622. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.029

Guh, D., Zhang, W., Bansback, N., Amarsi, Z., Birmingham, C., & Anis, H. (2009). The

incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 9, 120. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

Guttman, L. B.. 1954. A new approach to factor analysis: The radex. In P. F. Lazarsfeld

(Ed.). Mathematical thinking in the social sciences (pp. 258348). New York, NY:

Columbia University Press.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data

analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hambleton, R., & Bollwark, J. (1991). Adapting tests for use in different cultures: Technical

issues and methods. Bulletin of the International Test Commission, 18, 332.

Haslam, D. W., & James, W. P. (2005). Obesity. The Lancet, 366, 11971209.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

24

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Hersch, J. (2011). Skin color, physical appearance, and perceived discriminatory treatment.

The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40, 671678. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2011.05.006

Hu, L-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure

analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling:

A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 155. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Huizinga, M. M., Bleich, S. N., Beach, M. C., Clark, J. M., & Cooper, L. A. (2010).

Disparity in physician perception of patients adherence to medications by obesity

status. Obesity, 18, 19321937. doi:10.1038/oby.2010.35

Juregui-Lobera, I., Rivas-Fernndez, M., Montaa-Gonzlez, M. T., & Morales-Milln,

M. T. (2008). Influencia de los estereotipos en la percepcin de la obesidad. Nutricin

Hospitalaria, 23, 319325.

Kaiser, H. F. (1958). The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis.

Psychometrika, 23, 187200. doi:10.1007/BF02289233

Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second generation Little Jiffy. Psychometrika, 35, 401415.

doi:10.1007/BF02291817

Kim, J., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). An introduction to factor analysis: What it is and how

to do it. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

King, D. (2011). The future challenge of obesity. The Lancet, 378, 743744. doi:10.1016/

S0140-6736(11)61261-0

Kline, R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY:

Guilford Press.

Lewis, R. J., Cash, T. F., & Bubb-Lewis, C. (1997). Prejudice toward fat people: The

development and validation of the Anti-fat Attitudes Test. Obesity Research, 5, 297

307. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00555.x

Magallares, A., & Morales, J-F. (2013). Gender differences in antifat attitudes. Revista de

Psicologa Social, 28, 113119. doi:10.1174/021347413804756014

McClure, K., Puhl, R., & Heuer, C. (2011). Obesity in the news: Do photographic images

of obese persons influence antifat attitudes? Journal of Health Communication, 16,

359371. doi:10.1080/10810730.2010.535108

Morrison, T. G., & OConnor, W. E. (1999). Psychometric properties of a scale measuring

negative attitudes toward overweight individuals. The Journal of Social Psychology,

139, 436445. doi:10.1080/00224549909598403

OBrien, K. S., Latner, J. D., Ebneter, D., & Hunter, J. (2013). Obesity discrimination:

The role of physical appearance, personal ideology, and anti-fat prejudice.

International Journal of Obesity, 37, 455460. doi:10.1038/ijo.2012.52

Petrowski, K., Paul, S., Albani, C., & Brhler, E. (2012). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Trier Inventory for Chronic Stress (TICS) in a representative

German sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, 110. doi:10.1186/14712288-12-42

Puhl, R., & Heuer, C. (2009). The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity, 17,

941964. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.636

Puhl, R., Heuer, C., & Brownell, K. 2010. Stigma and social consequences of obesity. In

P. Kopelman, I. Caterson & W. Dietz (Eds.). Clinical obesity in adults and children

(pp. 2540). New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rodrguez-Rodrguez, E., Lpez-Plaza, B., Lpez-Sobaler, M., & Ortega, R. (2011).

Prevalencia de sobrepeso y obesidad en adultos espaoles. Nutricin Hospitalaria, 26,

355363.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics. New York, NY:

Harper Collins.

Teachman, B. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2001). Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: Is anyone immune? International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic

Disorders, 25, 15251531. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801745

Antifat Attitudes Scale / Escala de Actitud Antiobesos

25

Turnbull, J., Heaslip, S., & McLeod, H. (2000). Pre-school childrens attitudes to fat and

normal male and female stimulus figures. International Journal of Obesity, 24,

17051706. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801462

Van Groen, M., Klooster, P., Taal, E., Van de Laar, M., & Glas, C. (2010). Application of

the health assessment questionnaire disability index to various rheumatic diseases.

Quality of Life Research, 19, 12551263. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9690-9

World Health Organization. (2000). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Technical report series No. 894). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Appendix

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

Dislike

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

I really dont like fat people much.

I dont have many friends that are fat.

I tend to think that people who are overweight are a little untrustworthy.

Although some fat people are surely smart, in general, I think they tend not to be

quite as bright as normal weight people.

I have a hard time taking fat people too seriously.

Fat people make me somewhat uncomfortable.

If I were an employer looking to hire, I might avoid hiring a fat person.

Fear of fat

(8) I feel disgusted with myself when I gain weight.

(9) One of the worst things that could happen to me would be if I gained 25 pounds.

(10) I worry about becoming fat.

Willpower

(11) People who weigh too much could lose at least some part of their weight through

a little exercise.

(12) Some people are fat because they have no willpower.

(13) Fat people tend to be fat pretty much through their own fault.

Apndice

Antipata

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

No me gusta mucho la gente gorda.

No tengo muchos amigos/as que sean gordos.

Tiendo a pensar que la gente con sobrepeso son de poca confianza.

Aunque algunas personas gordas sean seguramente inteligentes, en general, creo

que no son tan brillantes como la gente con un peso normal.

(5) Me cuesta tomar en serio a una persona gorda.

(6) La gente gorda me hace sentir algo incmodo/a.

(7) Si fuera un empresario buscando a alguien que contratar, evitara contratar a una

persona gorda.

26

A. Magallares and J.-F. Morales

Miedo a la Gordura

(8) Me siento asqueado/a conmigo mismo/a cuando gano algo de peso.

(9) Una de las peores cosas que me podran pasar es que ganara unos kilos de peso.

(10) Me preocupa ponerme gordo/a.

Voluntad

Downloaded by [UNED] at 01:28 13 November 2014

(11) La gente que pesa mucho podra perder algo de su peso con un poco de ejercicio.

(12) Alguna gente est gorda porque no tiene fuerza de voluntad.

(13) La gente gorda tiene ese peso principalmente por su propia culpa.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- <![CDATA[Hacia una práctica comprometida con la justicia social]]>: <![CDATA[Manual de entrenamiento de profesionales de la salud mental]]>De la Everand<![CDATA[Hacia una práctica comprometida con la justicia social]]>: <![CDATA[Manual de entrenamiento de profesionales de la salud mental]]>Încă nu există evaluări

- Problemas de Convivencia en El PerúDocument2 paginiProblemas de Convivencia en El PerúKaren Chahuaris100% (3)

- Taller Conducta Suicida FinalDocument22 paginiTaller Conducta Suicida FinalChristian Vargas RivasplataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intervenciones Terapeuticas-Psicologia ClinicaDocument16 paginiIntervenciones Terapeuticas-Psicologia Clinicadaniela ganchozo zambranoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manual - Practicas - Psicología Experimental IIDocument94 paginiManual - Practicas - Psicología Experimental IIgaviota_valenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psicología Positiva Investigación y AplicacionesDocument10 paginiPsicología Positiva Investigación y AplicacionesmarcelocorreoÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Vida Personal Del PsicoterapeutaDocument7 paginiLa Vida Personal Del PsicoterapeutajuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- HHSS y Competencia SocialDocument40 paginiHHSS y Competencia SocialSonia García PardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-Terapia Familiar Genero PDFDocument25 pagini1-Terapia Familiar Genero PDFNeus Bastida Reguill100% (2)

- Serafín Gómez Et Al. - Teoría de Los Marcos Relacionales: Algunas Implicaciones para La Psicopatología y La PsicoterapiaDocument18 paginiSerafín Gómez Et Al. - Teoría de Los Marcos Relacionales: Algunas Implicaciones para La Psicopatología y La PsicoterapiaIrving Pérez MéndezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Act Habilidades SocialesDocument3 paginiAct Habilidades SocialesnautilusmetastasenÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Psicologia Posmoderna y La Retorica de La Realidad (Part 2 PDFDocument5 paginiLa Psicologia Posmoderna y La Retorica de La Realidad (Part 2 PDFJoelOlivoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etica 2Document8 paginiEtica 2Juan VieraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rastros y huellas en las fronteras de la psicoterapia sistémica: Tomo II - HuellasDe la EverandRastros y huellas en las fronteras de la psicoterapia sistémica: Tomo II - HuellasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Análisis teórico y experimental en psicología y salud: Algunas contribuciones mexicanasDe la EverandAnálisis teórico y experimental en psicología y salud: Algunas contribuciones mexicanasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psicología - La ManipulacionDocument16 paginiPsicología - La ManipulacionlischyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lineamientos de política pública sobre violencia de géneroDe la EverandLineamientos de política pública sobre violencia de géneroÎncă nu există evaluări