Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Developing and Implementing A Smoking Cessation Intervention in Primary Care in Nepal

Încărcat de

COMDIS-HSDTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Developing and Implementing A Smoking Cessation Intervention in Primary Care in Nepal

Încărcat de

COMDIS-HSDDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Developing and Implementing a Smoking Cessation Intervention

in Primary Care in Nepal

Sushil Baral ;Sudeepa Khanal; Shraddha Manandar; Dilip Kumar Sah; Kamran Siddiqi; Helen Elsey

BACKGROUND

Prevalence of tobacco among those over 15 years is estimated to be 31.6% overall, 52% among men and 13% among women. Use of smokeless

tobacco is also high, particularly chewing tobacco, with 38% of men and 6% of women using this form of tobacco (1). Despite this high smoking

prevalence there are no smoking cessation services in routine primary care. Respiratory conditions are one of the most common reasons for

presenting at primary care with 17.1% of male patients and 11.3% of female patients having a respiratory condition (2). There is evidence of

effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of number of psychological and pharmacological treatments for tobacco dependence, particularly where

advice is given by trained health professionals (3)

Aim: To develop and test the feasibility of a behavioural support intervention to promote smoking cessation within the in primary care in Nepal.

The study used a combination of qualitative methods SETTING

USE OF BEHAVIOUR CHANGE TECHNIQUES

METHODS

and action research to understand the barriers and

facilitators to implementation. Patients receiving the

intervention were followed up over a 3 month period

to gain their feedback on the intervention and to

identify those who had quit.

Evidence Review

Phase 1

21 qualitative Interviews with

lung health patients and FGDs

with PHC staff

Phase 2

Intervention development

workshop

Action Research & Baseline

Fagerstrom and CO

The intervention was tested in 3 primary health care centres (PHCCs)

selected based on sufficient patient flow, training of staff in WHOs

Practical Approach to Lung Health. 2 PHCCs were in a rural location in

the Terai plains and 1 PHCC was in urban Kathmandu.

INTERVENTION

Intervention design drew on initial ;qualitative work with smokers with

respiratory conditions and focus groups with health workers. Ministry of

Health and Population staff participated in a design workshop and

ultimately endorsed all materials. Training was provided to all the health

workers in their facilities.

The intervention drew on Michie et als (4) identified behaviour change

techniques (BCTs), as illustrated on the Quit Card shown below..

BCT 4 &10 : prompt

specific goal setting

by setting quit day.

BCT 6 : provide general

encouragement for self

efficacy and motivation

Quit Card showing use of

Behaviour Change Techniques

BCT 12 : prompt

self monitoring

behaviour by

ticking days quit.

Materials include:

Posters on the dangers of smoking and

chewing tobacco

BCT 5: identifying

Phase 3

barriers and coping

Follow up at 3 months

Poster

advertising

the

smoking

cessation

Fine-tune intervention

Fagerstrom and CO monitors

strategies to build

service in primary health clinics

self efficacy and

Leaflets for patients on the dangers of

skills to overcome

ACTION RESEARCH

smoking and chewing tobacco

barriers

To understand the barriers and facilitators to implementation

Flip book to be used by health workers in a

BCT 24: Keeping

in primary care, researchers facilitated action research

motivation by

meetings with the health workers in the 3 PHCCs. The groups brief counselling session

identifying and

Quit card to support abstinence

reflected on the implementation process and tried different

recording why

strategies to overcome any challenges over a 3 month period. DVD is under development

they want to quit.

Key Findings from the Action Research

FOLLOW UP RESULTS

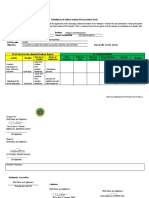

Patient Flow through

1) Intervention for all patients: Initially the intervention was

It was only possible to trace a total of 27 patients out of the 44

the Intervention

planned for respiratory patients only. However, health

who had received the counselling from the health worker. All

workers in all 3 PHCCs were adamant that the intervention

patients provided a CO sample, completed a questionnaire and

should be made available to all patients. The materials

provided feedback on the different aspects of the intervention and

were changed to include risk of tobacco use to cardiotheir experience of trying to quit. Patients were defined as having

vascular health and during pregnancy. The intervention

quit if they had a CO reading of 9 ppm and had smoked no more

was then offered to all patients in OPD.

than 5 cigarettes since their quit day.

2) Identifying smokers: Although health workers were keen

Urban PHCC Rural PHCC 1 Rural PHCC 2 Total

to open the intervention to all patients, in reality this was

challenging to implement due to the high patient numbers

4416

5062

2852

12330

Total out patients

particularly in clinics for reproductive and child health.

over 3 month

period

Patients were reluctant to admit to smoking when asked

Smokers identified 56 (1.3%)

29 (0.6%)

19 (0.7%)

104 (0.8%)

by the health worker. The overcrowded consultation room

QUALITATIVE FINDINGS

(as a % of total out

and manner of the health worker were identified as

patients)

undermining patients willingness to admit their habit. To

Smokers receiving 13 (23.2%) 18 (62.1%)

13 (68.4%)

44 (42.3%)

overcome this the team tried the use of volunteers to

counselling (as a %

sensitise communities of the availability of the cessation

of identified

programme and the use of PHCC support staff to

smokers)

encourage patients to be open. However limited numbers

Those. traced at 3 5 (38.5%)

12 (66.7%)

10 (76.9%)

27 (61.4%)

of smokers were identified, particularly as a proportion of

months follow up

all out patients in the PHCCs.

(as a % of those

counselled)

3) Recording and reporting: The main register in the PHCCs

Smokers who quit 1 (20%)

5 (41.7%)

4 (40%)

10 (37%)

did not have space to record smoking status. As these

(as a % of those

PHCCs were implementing WHOs PAL approach, the PAL

counselled)

register was used to record smoking, however health

workers did not fully understand the categories or

Feedback on the Intervention

Fagerstrom assessment tool in the PAL register as this was

The majority of patients (74%) were satisfied by the health workers

in English and had not been covered in depth in their PAL

support during counselling. Where patients complained about their

training. The researchers supported the health workers in

interaction with the health worker, they lost motivation to quit.

this aspect. The Government of Nepal now plans to

including smoking status in the main PHCC register.

The majority of patients, particularly those with low literacy levels,

did not find the quit card useful and had lost their card.

4) High use of Smokeless Tobacco: the original intervention

materials did not include chewing tobacco. Given the high

While two patients reported that they had stopped chewing tobacco,

prevalence in the two Terai PHCCs, warnings of the

three admitted taking up chewing to substitute cigarettes.

dangers of chewing tobacco were added to the materials.

Patients preferred graphic pictures and photographs of the physical damage caused by smoking or

5) Motivation of Health Workers: only a few health workers were motivated to deliver the

chewing tobacco.

intervention. As the intervention was not seen as a part of core activities and was not a

Confusion over Not a puff message: Many patients had managed to reduce the number of cigarettes

performance indicator for the PHCC, the health workers did not prioritise the intervention.

smoked, but had not appreciated the need to identify a quit day and not smoke again.

This lack of motivation impacted on the number of identified and counselled and the quality

The most common barrier to quitting identified was being encouraged to smoke by friends. Conversely,

of the counselling provided. Establishing smoking cessation as a core, routine service with

when families were supportive, this was a facilitator to quitting.

monitoring from central and district health departments is needed to essential for the

effective and sustainable implementation of the programme.

REFERENCES

1. Ministry of Health and Population (2012) Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011 Population

DivisionGovernment of Nepal, New ERA Nepal and ICF International, U.S.A

2.WHO (2008) Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008:. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2008.

3. Gorin SS & Heck JE (2004) Meta-analysis of the efficacy of tobacco counselling by health care providers. Cancer

Epidemiology and Biomarkers Preventions 13, 20122022.

4.Michie et al (2008) From Theory to Intervention: Mapping Theoretically Derived Behavioural Determinants to

Behaviour Change Techniques Applied psychology: an international review, 2008, 57 (4), 660680

, Please be in touch: Helen Elsey (University of Leeds) h.elsey@leeds.ac.uk Sudeepa Khanal

(Health Research and Social Development Forum, HERD, Nepal)

sudeepa.khanal@herd.org.np

CONCLUSIONS

The study demonstrates that it is feasible to implement a smoking cessation intervention in primary

care, particularly if the intervention is target at those patients who are motivated to quit. The

patients who received the counselling felt the intervention helped them to quit.

Greater attention to the not a puff rule was needed in the training and subsequent patient

counselling sessions. In areas with high prevalence of smokeless tobacco, particular attention is

needed within the intervention to ensure that quitters do not take up chewing tobacco to

compensate for cigarettes.

A limitation of the study is the low number of smokers identified and receiving the intervention. This

means that conclusions about effectiveness can not be drawn from this small sample.

Embedding smoking cessation within routine primary care is key to successful delivery. This requires

effective reporting and supervision mechanisms within the health system.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Principles and Application of Evidence-Based Public Health PracticeDe la EverandPrinciples and Application of Evidence-Based Public Health PracticeSoundappan KathirvelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synthesispaperebpsummative AnjouligerezDocument9 paginiSynthesispaperebpsummative Anjouligerezapi-325112936Încă nu există evaluări

- Synthesis PaperDocument14 paginiSynthesis Paperapi-284053760Încă nu există evaluări

- Tobacco Cessation Treatment PlanDocument7 paginiTobacco Cessation Treatment PlanyellowishmustardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective Smoking CEssationDocument41 paginiEffective Smoking CEssationDhruva PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shared Decision-Making For Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Smoking CessationDocument7 paginiShared Decision-Making For Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Smoking CessationIJPHSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument196 paginiTreating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guidelinesah770Încă nu există evaluări

- Osong Public Health and Research PerspectivesDocument8 paginiOsong Public Health and Research PerspectivesAmbarsari HamidahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Online Tobacco Cessation Education for Psychiatric NursesDocument9 paginiOnline Tobacco Cessation Education for Psychiatric NursesThaís MouraÎncă nu există evaluări

- ProposalDocument3 paginiProposalAbdullahAlmasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Restrictions and Treatment For Smoking: Policies and Procedures in Psychiatric Inpatient Units in AustraliaDocument9 paginiSmoking Restrictions and Treatment For Smoking: Policies and Procedures in Psychiatric Inpatient Units in AustraliayasernetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synthesis ReviewDocument8 paginiSynthesis Reviewapi-315731045Încă nu există evaluări

- Summerize The F-WPS OfficemDocument4 paginiSummerize The F-WPS OfficemA HÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Cessation ProgramDocument5 paginiSmoking Cessation ProgrampeterjongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking CessationDocument4 paginiSmoking CessationAimee GutierrezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Protocol UpdatedDocument22 paginiStudy Protocol Updatedknj210110318Încă nu există evaluări

- Research ProposalDocument3 paginiResearch Proposaljamilu ABUBAKARÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Correlated With Smoking Cessation Success in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cohort Study in TaiwanDocument9 paginiFactors Correlated With Smoking Cessation Success in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cohort Study in TaiwanKhaziatun NurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Cessation Counseling Program: A Pilot Study On College SmokersDocument9 paginiSmoking Cessation Counseling Program: A Pilot Study On College SmokersFikrianti SurachmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Population Level Analysis of Changes in AustraliDocument17 paginiA Population Level Analysis of Changes in AustraliYuning tyas Nursyah FitriÎncă nu există evaluări

- EBP Smoking CessationDocument9 paginiEBP Smoking CessationAli KayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Helping Smokers To Decide On The Use of Efficacious Smoking Cessation Methods: A Randomized Controlled Trial of A Decision AidDocument10 paginiHelping Smokers To Decide On The Use of Efficacious Smoking Cessation Methods: A Randomized Controlled Trial of A Decision AidFilip RalucaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 1Document6 paginiJurnal 1ChristianWicaksonoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessing The Effectiveness of HighDocument6 paginiAssessing The Effectiveness of HighEthel MachergianyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking BehaviorDocument8 paginiSmoking BehaviorYaoska Rivas RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optimizing Smoking Cessation Counseling in A University HospitalpdfDocument8 paginiOptimizing Smoking Cessation Counseling in A University HospitalpdfConstantin PopescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intervention For Smoking ReductionDocument15 paginiIntervention For Smoking Reductionben mwanziaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstract Motivation SetDocument241 paginiAbstract Motivation SetValentina CaprariuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Cessation or Reduction With Nicotine Replacement Therapy: A Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Trial With Nicotine Gum and InhalerDocument28 paginiSmoking Cessation or Reduction With Nicotine Replacement Therapy: A Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Trial With Nicotine Gum and InhalerSigit Harya HutamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Passed and Cleared' - Former Tobacco Smokers' Experience in Quitting SmokingDocument9 paginiPassed and Cleared' - Former Tobacco Smokers' Experience in Quitting SmokingzikriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shiatsu and Drug and Substance and Alcohol AbuseDocument7 paginiShiatsu and Drug and Substance and Alcohol AbuseStreza G VictorÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Journal of Oncology Nursing: A A B C A D C eDocument8 paginiEuropean Journal of Oncology Nursing: A A B C A D C eAnkga MahaltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dapus Referat No.4Document7 paginiDapus Referat No.4Muhammad AkrimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tobacco Cessation in India: Benefits, Hurdles and ApproachesDocument3 paginiTobacco Cessation in India: Benefits, Hurdles and ApproachesHakim ShaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infographic: Can Behaviour Change Support Reduce Tobacco Use in Nepal?Document1 paginăInfographic: Can Behaviour Change Support Reduce Tobacco Use in Nepal?COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- New PDFDocument36 paginiNew PDFpopov357Încă nu există evaluări

- Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing and Cost Outcomes For Older People: A National Population StudyDocument10 paginiPotentially Inappropriate Prescribing and Cost Outcomes For Older People: A National Population Studybiotech_vidhyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Facilitated Pa-Depression-2Document13 paginiFacilitated Pa-Depression-2api-332791374Încă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Cessation Literature ReviewDocument8 paginiSmoking Cessation Literature Reviewafmzvaeeowzqyv100% (1)

- HEALTH IMPROVEMENT AFTER SMOKING CESSATIONDocument5 paginiHEALTH IMPROVEMENT AFTER SMOKING CESSATIONAmin Mohamed Amin DemerdashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obesity in Mental Health Secure UnitsDocument70 paginiObesity in Mental Health Secure UnitsDaniel DubeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Cessation Program: RationaleDocument5 paginiSmoking Cessation Program: RationaleJovic PocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving Patient Education About Tobacco Withdrawal and Nicotine Gum Use by Registered Nurses in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Feasibility StudyDocument10 paginiImproving Patient Education About Tobacco Withdrawal and Nicotine Gum Use by Registered Nurses in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Feasibility StudyIzzat HafizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Promotion Activities in Bandung Public Health Centre (Puskesmas)Document9 paginiHealth Promotion Activities in Bandung Public Health Centre (Puskesmas)Astri Dwi ParamitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Makalah KesehatanDocument9 paginiMakalah KesehatanNini RahmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2019 Article 4118Document10 pagini2019 Article 4118Nino AlicÎncă nu există evaluări

- EBM of DyspepsiaDocument228 paginiEBM of DyspepsiaxcalibursysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jama Stop SmokeDocument8 paginiJama Stop Smokeandrew herringÎncă nu există evaluări

- NExit EssayDocument8 paginiNExit EssayNek Arthur JonathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- research paper-2Document9 paginiresearch paper-2api-741551545Încă nu există evaluări

- Art:10.1186/1471 2458 13 315Document8 paginiArt:10.1186/1471 2458 13 315Moh AdibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Intervention and Smoking Cessation: A Meta-AnalysisDocument17 paginiNursing Intervention and Smoking Cessation: A Meta-AnalysisingevelystareslyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking interventions in primary careDocument9 paginiSmoking interventions in primary careAlejandro Javier Torres MorenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Revision SheetDocument11 paginiHealth Revision Sheetapi-317980894100% (1)

- Assessment of tobacco control advocacy training program among Chinese public health studentsDocument7 paginiAssessment of tobacco control advocacy training program among Chinese public health studentsDavid TiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking Among Physicians in Syria: Do As I Say, Not As I Do!Document4 paginiSmoking Among Physicians in Syria: Do As I Say, Not As I Do!Salah Eddine BoulmakoulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoking CessationDocument5 paginiSmoking CessationHafiz RabbiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Add 12140Document9 paginiAdd 12140imadhassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cigarette Revistion Group 3Document104 paginiCigarette Revistion Group 3Neil Christian TadzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expanding Mental Health Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From Initial Experiences in Lubombo RegionDocument8 paginiExpanding Mental Health Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From Initial Experiences in Lubombo RegionCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decentralising Non-Communicable Disease Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From A Pilot Study in Lubombo RegionDocument8 paginiDecentralising Non-Communicable Disease Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From A Pilot Study in Lubombo RegionCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- In-Country Public-Private Partnerships Hold The Key To Promoting Inclusiveness in Dutch Trade and International Cooperation AgendaDocument2 paginiIn-Country Public-Private Partnerships Hold The Key To Promoting Inclusiveness in Dutch Trade and International Cooperation AgendaCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving The Quality of Care at Community Clinics in Rural Bangladesh Through New ApproachesDocument4 paginiImproving The Quality of Care at Community Clinics in Rural Bangladesh Through New ApproachesCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influencing TB Policy and Practice in Bangladesh Using A Public-Private Mix ApproachDocument2 paginiInfluencing TB Policy and Practice in Bangladesh Using A Public-Private Mix ApproachCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction in Rural China - Policy RecommendationsDocument1 paginăCardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction in Rural China - Policy RecommendationsCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Gender Mainstreaming Is Important When Planning and Implementing Health Interventions: Examples From COMDIS-HSDDocument6 paginiWhy Gender Mainstreaming Is Important When Planning and Implementing Health Interventions: Examples From COMDIS-HSDCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supporting Roll-Out of Revised Dengue Prevention and Control Guidelines in MyanmarDocument8 paginiSupporting Roll-Out of Revised Dengue Prevention and Control Guidelines in MyanmarCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using Behaviour Change Interventions To Decrease Tobacco Use in NepalDocument4 paginiUsing Behaviour Change Interventions To Decrease Tobacco Use in NepalCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rational Use of Antibiotics by Community Health Workers (CHWS) and Caregivers in ZambiaDocument1 paginăRational Use of Antibiotics by Community Health Workers (CHWS) and Caregivers in ZambiaCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving Treatment For Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Patients - Lessons From Shandong Province, ChinaDocument2 paginiImproving Treatment For Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Patients - Lessons From Shandong Province, ChinaCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Can Public-Private Partnerships Enhance The Use of Long Acting Contraceptive Methods in Bangladesh?Document4 paginiHow Can Public-Private Partnerships Enhance The Use of Long Acting Contraceptive Methods in Bangladesh?COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving Rational Use of Antibiotics in Childhood Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Rural ChinaDocument2 paginiImproving Rational Use of Antibiotics in Childhood Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Rural ChinaCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Reporting in The Kathmandu Post, Nepal. September 2013-August 2014Document22 paginiHealth Reporting in The Kathmandu Post, Nepal. September 2013-August 2014COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Should National TB Programmes Prioritise Co-Morbid Mental Health Disorders in MDR-TB Patients?Document4 paginiWhy Should National TB Programmes Prioritise Co-Morbid Mental Health Disorders in MDR-TB Patients?COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decentralising Services For Diabetes and Hypertension in Low - and Middle-Income Countries: 6 Key Policy Areas For Service PlannersDocument4 paginiDecentralising Services For Diabetes and Hypertension in Low - and Middle-Income Countries: 6 Key Policy Areas For Service PlannersCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decentralising Non-Communicable Disease Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From A Pilot Study in Lubombo RegionDocument8 paginiDecentralising Non-Communicable Disease Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From A Pilot Study in Lubombo RegionCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addressing Health Systems Challenges For Diabetes Care in PakistanDocument2 paginiAddressing Health Systems Challenges For Diabetes Care in PakistanCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using Behaviour Change Interventions To Decrease Tobacco Use in NepalDocument1 paginăUsing Behaviour Change Interventions To Decrease Tobacco Use in NepalCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structured pre-ART' Care: A Pathway To Better Health For People With HIVDocument4 paginiStructured pre-ART' Care: A Pathway To Better Health For People With HIVCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- TB Care For Garment Factory Workers Using PPP in Bangladesh May2013Document4 paginiTB Care For Garment Factory Workers Using PPP in Bangladesh May2013COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Male Circumcision: Do Women in Swaziland Welcome It For Their Sons and at What Age?Document4 paginiMedical Male Circumcision: Do Women in Swaziland Welcome It For Their Sons and at What Age?COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Health Issues Can Nepali Journalists Write About?Document1 paginăWhat Health Issues Can Nepali Journalists Write About?COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schistosomiasis: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Nampula Province, Mozambique (Portuguese Version)Document2 paginiSchistosomiasis: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Nampula Province, Mozambique (Portuguese Version)COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extended Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention: Is It Effective and Acceptable in Areas With Longer Rainy Seasons in Ghana?Document4 paginiExtended Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention: Is It Effective and Acceptable in Areas With Longer Rainy Seasons in Ghana?COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strengthening Service Delivery For Malaria in Pregnancy - An MHealth Pilot InterventionDocument8 paginiStrengthening Service Delivery For Malaria in Pregnancy - An MHealth Pilot InterventionCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schistosomiasis: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Nampula Province, MozambiqueDocument2 paginiSchistosomiasis: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Nampula Province, MozambiqueCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women and Their Mental and Social Wellbeing During Multi-Drug Resistant TB Treatment in NepalDocument4 paginiWomen and Their Mental and Social Wellbeing During Multi-Drug Resistant TB Treatment in NepalCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Reporting in The Kathmandu Post: 2013 - 2014Document1 paginăHealth Reporting in The Kathmandu Post: 2013 - 2014COMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addressing Barriers To IPT2 Uptake in UgandaDocument4 paginiAddressing Barriers To IPT2 Uptake in UgandaCOMDIS-HSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug Study TranexamicDocument3 paginiDrug Study Tranexamicalpha mayagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expository EssayDocument9 paginiExpository Essayapi-314337183Încă nu există evaluări

- 0008 Hydrochlorothiazide and Prevention of Kidney-Stone Recurrence Nejmoa2209275Document11 pagini0008 Hydrochlorothiazide and Prevention of Kidney-Stone Recurrence Nejmoa2209275Iana Hércules de CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chairside Talk Implementation for Plaque ControlDocument7 paginiChairside Talk Implementation for Plaque ControlYuli Fitriyani Terapi Gigi Alih JenjangÎncă nu există evaluări

- ZZZZZZZDocument34 paginiZZZZZZZmikeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reconsider Licensure Appeal for Top StudentDocument6 paginiReconsider Licensure Appeal for Top StudentFrancis Edrian CellonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics in Midwifery PowerpointDocument24 paginiEthics in Midwifery PowerpointEden NatividadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plenary Session. 1. Challenges-Opportunity of CVD Services in Universal Coverage. Dr. Anwar Santoso SPJPKDocument32 paginiPlenary Session. 1. Challenges-Opportunity of CVD Services in Universal Coverage. Dr. Anwar Santoso SPJPKannisÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 The Comparison of The Effects of Clinical Pilates Exercises With and Without Childbirth Training On Pregnancy and Birth ResultsDocument28 pagini6 The Comparison of The Effects of Clinical Pilates Exercises With and Without Childbirth Training On Pregnancy and Birth Resultseamaeama7Încă nu există evaluări

- 9Document3 pagini9Octavian BoaruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jacobson Progressive Muscle Relaxation TechniqueDocument3 paginiJacobson Progressive Muscle Relaxation TechniqueAleena ThakurtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2019 Guide For ImmunizationDocument195 pagini2019 Guide For ImmunizationReigner paul DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- P.Chitra Resume PDFDocument2 paginiP.Chitra Resume PDFSam rajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide Services Children ASDDocument52 paginiGuide Services Children ASDCornelia AdeolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Counseling Professionals Roles FunctionsDocument4 paginiCounseling Professionals Roles FunctionsReign ArmaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Medical Service Providers in Accra 2019Document3 paginiList of Medical Service Providers in Accra 2019Law CaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Childhood Psoriasis Methotrexate TreatmentDocument5 paginiChildhood Psoriasis Methotrexate TreatmentNana AdistyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pengetahuan Ibu Tentang Mobilisasi Dini Pasca Persalinan Normal Pervaginam Di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Labuhan Rasoki Kecamatan Padangsidimpuan Tenggara Tahun 2018Document6 paginiPengetahuan Ibu Tentang Mobilisasi Dini Pasca Persalinan Normal Pervaginam Di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Labuhan Rasoki Kecamatan Padangsidimpuan Tenggara Tahun 2018Geuman ChajgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Touch Therapy & Reiki TherapyDocument21 paginiTouch Therapy & Reiki TherapyBindu GCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ef205 Unit 2 Assignment 1Document5 paginiEf205 Unit 2 Assignment 1api-601333476Încă nu există evaluări

- BookDocument157 paginiBookMaria Magdalena DumitruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tips NLE 2013Document14 paginiTips NLE 2013Dick Morgan Ferrer100% (6)

- 18 LeybovicDocument8 pagini18 LeybovicAlvaro galilea nerinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Share FORM 10 - Workplace Application Evaluation ToolDocument3 paginiShare FORM 10 - Workplace Application Evaluation ToolRocel Ann CarantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- !!!!!! Black StainsDocument7 pagini!!!!!! Black StainsGhimpu DanielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intravenous Parenteral TherapyDocument110 paginiIntravenous Parenteral TherapyDarran Earl Gowing100% (1)

- Analisa Jurnal Kelompok 9 (The History of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing Education and Practice)Document9 paginiAnalisa Jurnal Kelompok 9 (The History of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing Education and Practice)Viola AlvionitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- About Ziauddin UniversityDocument3 paginiAbout Ziauddin Universityaamrah_mangoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visit Reportof IncDocument5 paginiVisit Reportof IncSimran Josan100% (1)

- KG College of Nursing VisitDocument7 paginiKG College of Nursing VisitShubha JeniferÎncă nu există evaluări