Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Teaching and Teacher Education: Jan Van Tartwijk, Perry Den Brok, Ietje Veldman, Theo Wubbels

Încărcat de

elenamarin1987Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Teaching and Teacher Education: Jan Van Tartwijk, Perry Den Brok, Ietje Veldman, Theo Wubbels

Încărcat de

elenamarin1987Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Teaching and Teacher Education

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tate

Teachers practical knowledge about classroom management in

multicultural classrooms

Jan van Tartwijk a, *, Perry den Brok b,1, Ietje Veldman a, 2, Theo Wubbels c, 3

a

ICLON Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching, Leiden University, P.O. Box 905, 2300 AX Leiden, The Netherlands

Eindhoven School of Education, Technical University Eindhoven, P.O. Box 513, 5600 MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands

c

Department of Pedagogical and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.140, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands

b

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 17 April 2007

Received in revised form 8 January 2008

Accepted 9 September 2008

Creating a positive working atmosphere in the classroom is the rst concern of many student and

beginning teachers in secondary education. Teaching in multicultural classrooms provides additional

challenges for these teachers. This study identied shared practical knowledge about classroom

management strategies of teachers who were successful in creating a positive working atmosphere in

their multicultural classrooms. Twelve teachers were selected who were regarded as successful classroom managers in Dutch multicultural classes by their principals and students. Video-stimulated

interviews were used to elicit data about the practical knowledge of these teachers. The teachers were

aware of the importance of providing clear rules and correcting student behaviour whenever necessary,

but they also wanted to reduce potential negative inuences of corrections on the classroom atmosphere.

They aimed at developing positive teacherstudent relationships and adjusted their teaching methods

anticipating students responses. Most teachers seemed reluctant to refer to the cultural and ethnic

background of their students.

2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Classroom management

Teacher Knowledge

Multicultural classroom

1. Introduction

Veenman (1984) reviewed the literature on beginning teachers

concerns. He concluded that creating a positive working atmosphere in the classroom is the rst concern of most student and

beginning teachers in secondary education. Today, research ndings consistently show that student and beginning teachers still

regard this as their most serious challenge (Evertson & Weinstein,

2006a). Teaching in multicultural classrooms provides an additional challenge for these teachers.

In the USA, Australia and Europe, society is becoming increasingly multicultural. Weinstein (2003) notes that the increase of the

percentage of people of colour in the USA, puts a topsy-turvy spin

on the meaning of majority and minority. In the Netherlands, of

the 16 million population in 2007, about three million were either

born outside the Netherlands or had parents born outside the

Netherlands (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2007). About 1.7 of

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 31-71-527-3845.

E-mail addresses: jtartwijk@iclon.leidenuniv.nl (J. van Tartwijk), p.j.d.brok@

tue.nl (P. den Brok), veldman@iclon.leidenuniv.nl (I. Veldman), t.wubbels@uu.nl

(T. Wubbels).

1

Tel.: 31-40-247-4702.

2

Tel.: 31-71-527-4024.

3

Tel.: 31-30-253-3910.

0742-051X/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.005

these three million have their roots in non-western countries,

mostly Morocco, Turkey, Surinam, and the Dutch Antilles. As

a consequence, more and more the multicultural classroom becomes

the standard classroom. Multicultural classrooms are characterized by a diversity of ethnicity, religion, mother tongue, and cultural

traditions (Ben-Peretz, Eilam, & Yankelevitch, 2006). In the last

decades, a huge body of literature has become available about

multicultural classrooms. Much of this research is summarized in

the Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education (Banks &

McGee Banks, 2004). This literature focuses on, for instance, prejudice reduction, equity pedagogy, empowering the school culture,

and cultural biases in how content is presented and how knowledge is constructed (Banks, 2004).

One of the challenges that the multicultural classroom provides

for student and beginning teachers is the potential misunderstanding between students and teachers with different ethnic and

socio-cultural backgrounds (Ting-Toomey, 1999; Weinstein, Tomlinson-Clarke, & Curran, 2004). Another challenge is related to the

location of most multicultural schools, which are typically found in

urban areas. According to, for instance, Milner (2006) and Weiner

(2006), urban schools in the USA are not only characterized by large

ethnic and cultural diversity in the student population, but their

students also tend to live in socially and economically deprived

conditions. These schools tend to be larger and have fewer

resources than suburban schools. Student behaviour is often

454

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

problematic, and teacher turnover relatively high. In the Netherlands too, the large majority of the people with a non-western

background live in urban areas where social and economic problems tend to be concentrated. Teaching in schools in Dutch cities

may be less challenging for teachers than teaching in urban schools

in the USA, for instance because all schools in the Netherlands

receive equal government funding. But in the Netherlands too,

teaching in city schools with a large percentage of students with

a non-western background is regarded as more stressful than

teaching in other schools in the country. Not for nothing, the Dutch

Council for Education recently advised the Dutch government to

provide extra rewards for teachers willing to work in multicultural

classrooms in Dutch cities (Onderwijsraad, 2006).

Teacher education needs a knowledge base for the preparation

of student and beginning teachers for classroom management in

multicultural classrooms. Verloop, van Driel, and Meijer (2001:

443) dene a knowledge base of teaching as all profession-related

insights that are potentially relevant to the teachers activities.

These insights can pertain to formal theory, i.e., knowledge that is

usually generated by university-based researchers, and to shared

elements of teachers practical knowledge. Cochran-Smith and

Lytle (1999) refer to the former as knowledge-for-practice and the

latter as knowledge-in-practice. Practical knowledge consists of

teachers knowledge and beliefs about their own teaching practice.

It is developed through an integrative process rooted in teachers

own classroom practice and it guides teacher behaviour in the

classroom (Meijer, 1999). According to Verloop et al. (2001), an

exchange between theoretical principles, on the one hand, and

teacher expertise, on the other, is necessary for renement of this

knowledge base of teaching.

The recent publication of the Handbook of Classroom Management: Research, Practice and Contemporary Issues (Evertson &

Weinstein, 2006b) has brought together an impressive theoretical

foundation for a knowledge base about classroom management. In

the introductory chapter of this handbook, Evertson and Weinstein

(2006a: 4) describe classroom management as the actions

teachers take to create an environment that supports and facilitates

both academic and social emotional learning. They distinguish

four themes in contemporary research on classroom management.

The rst is the importance of positive teacherchild relationships

for effective classroom management. According to Evertson and

Weinstein, the teacher as a warm demander comes forward as

effective, particularly for students of colour, in this research. Warm

demanders are teachers who are warm, responsive, caring and

supportive, as well as holding high expectations of their students.

The second theme is classroom management as a social and moral

curriculum. This draws attention to the consequences of teachers

managerial decisions for students social, moral and emotional

development. A third theme is how classroom management strategies relying on punishment and external reward may negatively

inuence the classroom atmosphere. More proactive approaches to

prevent management problems are investigated. The nal theme

refers to the recognition that teachers must take into account

students characteristics, such as age, ethnicity, cultural background, and socio-economic status, when creating an orderly,

productive, and supportive classroom environment.

In their contribution to the Handbook of Classroom Management,

Woolfolk-Hoy and Weinstein (2006) summarize research ndings

on teachers knowledge about classroom management. This review

shows that the majority of teachers in secondary education tends to

a traditional or custodial orientation to classroom management. Teachers with such orientations believe in the teacher as the

authority, in a strict adherence to rules, and in a fair set of

punishments for infractions that increase in intensity aligned with

the severity of infractions. Most other teachers tend to a liberal

progressive or humanistic orientation to classroom

management. These teachers believe that democratic principles

should apply in all social situations, including schools and classrooms, and they emphasize self-discipline. Research about

teachers perceptions of the value of classroom management

strategies is also reviewed in this chapter. Generally, teachers seem

to prefer neutral or positive/supportive interventions over negative/punitive actions, but control-oriented strategies, such as

reminders of rules of behaviour, threats to punish, and actual

punishment, are seen as appropriate for hostile, aggressive,

disruptive, and deant students (Brophy & McCaslin, 1992).

Brown (2003) studied teachers knowledge about classroom

management in the specic context of urban schools in the USA

(often with a highly multicultural character). He interviewed thirteen primary and secondary effective urban teachers from several

cities across the USA. These teachers emphasized the importance of

developing a caring relationship with their students. They wanted

to demonstrate assertiveness through establishing and making

clear a set of academic expectations for students, and through

enforcing rules and behavioural policies. Several of these teachers

emphasized the need for knowledge about their students culturally rooted communication styles. Weinstein, Curran, and Tomlinson-Clarke (2003) also advise teachers to become knowledgeable

about the cultures and communities in which their students live,

and to teach their students mainstream ways to interact in social

situations, in order to succeed in dominant social spheres. At the

same time, teachers should not devalue students cultural practices

which are not part of the dominant cultural paradigm.

Recently, teachers knowledge and beliefs about classroom

management strategies in multicultural classrooms in a European

context, were investigated in an exploratory study by Wubbels, den

Brok, Veldman, and van Tartwijk (2006). In this study, focus-group

interviews with experienced and beginning teachers in Dutch

multicultural schools were used. To validate the ndings of the

focus-group interviews, an in-depth case study of one expert

teacher was carried out. In the focus-group interviews, the teachers

brought up and discussed the competence needed to successfully

manage their multicultural classrooms and mentioned a number of

specic classroom management strategies. According to the

teachers in the focus-groups, teaching in these classrooms requires

competence in Creating positive teacherstudent relations, Managing

and monitoring student behaviour, and Teaching for student attention

and engagement. Further, teachers should be interested in and

knowledgeable about their students cultural background and its

consequences for student behaviour.

The present study is a follow-up of the exploratory study by

Wubbels, den Brok, et al. (2006), and focuses on practical knowledge of teachers who are successful in creating a positive working

atmosphere in their multicultural classrooms in secondary education. It wants to contribute to the knowledge base about classroom

management by answering the question: Which elements of

practical knowledge underlying classroom management strategies,

are shared by teachers who are successful in creating a positive

working atmosphere in their multicultural classroom?

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

To identify teachers who were successful in creating a positive

working atmosphere in their multicultural classrooms, we rst

selected four schools for secondary education that collaborate

with the teacher education programs of our universities. These

schools were located in areas with a multicultural population and

had a multicultural student body. We then asked the principals of

these schools to help us contact teachers whom they regarded as

good classroom managers in multicultural classes and who might

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

be willing to participate in our research. We regarded a class as

multicultural when at least one-third of the students were born in

non-western European countries or had parents who were born

in these countries. Fifty teachers were nominated. In one multicultural class of each of these 50 teachers, we gathered data about

the students perceptions of their teachers interpersonal style

with the Questionnaire on Teacher Interaction (QTI: Wubbels,

Creton, & Hooymayers, 1985; Wubbels & Levy, 1991). Research has

shown that data gathered with the QTI are indicative for the

working climate in this classroom (Wubbels, Brekelmans, den

Brok, & van Tartwijk, 2006). Typical items are S/he is a good leader,

and S/he is someone we can depend on. Research using this

questionnaire has shown that eight typical interpersonal styles

can be distinguished (Brekelmans, Levy, & Rodriguez, 1993):

directive, authoritative, tolerant-authoritative, tolerant, uncertaintolerant, uncertain-aggressive, repressive, and drudging. Both

teachers and students usually prefer tolerant-authoritative,

authoritative, or directive interpersonal styles (Wubbels, Brekelmans, et al., 2006). These three styles all combine relatively high

levels of teacher inuence and teacherstudent afliation.

Compared to other teachers, teachers with such interpersonal

styles have a positive working atmosphere in their classrooms,

their students do well on standardized tests, and their students

are motivated for the subject and the lessons (Brekelmans et al.,

1993; Wubbels, Brekelmans, et al., 2006). The difference between

teachers with these three styles lies in the level of teacher

student afliation. Compared to directive teachers, authoritative

teachers have closer relationships with their students. Tolerantauthoritative teachers have the closest relationship with their

students (Wubbels, Brekelmans, et al., 2006).

Of the 50 teachers nominated by their principals as excellent

classroom managers, 12 were selected to participate in the study.

They were selected (1) because they were regarded by their

students as directive (three teachers), authoritative (three

teachers), or tolerant-authoritative (six teachers) and (2) because

they were willing and able to participate in the next phases of our

research project. In this article we will refer to the three directive

teachers as Daphne, Dave and Diana, to the three authoritative

teachers as Adrian, Alan and Albert, and to the six tolerantauthoritative teachers as Theo, Trudy, Tina, Tom, Terry and Thea.

One teacher, Alan, had a non-Dutch background. He was born in

Surinam and considered his ethnic and cultural background as nonDutch.

In Table 1, we report at which school the teachers taught, their

teaching experience (in years) and the composition of the classes.

On average the percentage of students with a non-western background was 61%. This percentage is highest in Dianas class (83%),

and lowest in those of Daphne and Thea (40%).

455

2.2. Data gathering

To gather data about these teachers practical knowledge of

classroom management strategies, we videotaped a lesson of each

teacher and conducted a teacher interview immediately after the

lesson. In the interviews the following procedure was used: The

researcher and the teacher watched the video-recording together.

The teachers were asked to stop the videotape whenever they

remembered thoughts, emotions or feelings. The researcher also

stopped the videotape at specic moments, such as the start and

end of the lesson, at transitions between lesson phases or activities,

or when problems related to classroom management occurred.

After each stop, the teachers were asked to describe the situation,

and their own behaviour and thoughts during these moments. The

interviewers were cautious to phrase their questions in such a way

that the teachers answers and remarks were inuenced as little as

possible.

This interview resembles the stimulated-recall interview technique described by Yinger (1986). The difference is that in stimulated-recall interviews, teachers are asked to describe their thoughts

during their lesson, whereas in our interviews, teachers also elaborated on their teaching and their students in general. For this

reason, we refer to the interview as a video-stimulated interview.

2.3. Analyses

All 12 interviews were transcribed and coded using the software

tool Atlas.ti. First, statements were distinguished within the transcribed interviews: a statement was dened as one or a sequence of

sentences relating to one specic occurrence or topic. Thus, 611

statements were distinguished. The rst three authors of this

article subsequently coded the statements. During the process,

coding results were discussed regularly and all differences were

resolved by reaching consensus. Coding involved three phases.

In the rst phase, the topic of all 611 statements was coded using

six categories: classroom management strategies; students thinking

or behaviour; required teacher attitudes and knowledge; student

background; teaching a subject; and other (e.g. about the research

project). In 332 out of the 611 statements, teachers talked about

their classroom management strategies.

In the second phase of coding, these 332 statements were coded

for the type of classroom management strategy. As initial categories

for the second phase we employed the categories describing the

strategies mentioned by the beginning and experienced teachers in

the focus-group interviews conducted by Wubbels, den Brok, et al.

(2006). Whenever a strategy had been mentioned that did not

match with one of the categories from the focus-group interviews,

a new category was added or the category label was reworded to

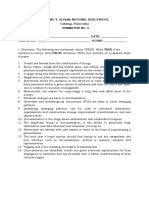

Table 1

Sample: teacher experience, school, and country of origin of the students

Teacher

Country of origin of student or parents

Name

School

Years of experience

Subject

Netherlands (%)

Turkey (%)

Morocco (%)

Surinam (%)

Diana

Theo

Daphne

Alan

Thea

Albert

Terry

Tina

Dave

Adrian

Tom

Trudy

Mean

1

1

2

2

2

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

24

21

9

16

8

18

4

12

20

23

16

4

14,6

Dutch

Drama

French

Geography

Dutch

Physical education

Mathematics

Dutch

English

German

English

French

17

57

60

40

60

52

37

50

25

18

25

30

39

4

14

30

35

20

26

37

28

13

18

5

11

20

63

13

7

Netherlands Antilles (%)

5

7

4

5

6

33

30

40

37

18

13

6

5

11

5

3

10

2

Other (%)

4

21

10

20

13

17

21

17

17

24

15

11

16

456

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

better match the data. When this occurred, earlier coding was

checked again. Memos were added to specify and elaborate the

category label meaning. As a result, the labels of the categories were

rened and their meaning was made explicit in the memos. This

helped us identify properties of the data and the concepts that were

emerging from them (cf. Charmaz, 2006). In the end, 30 categories

were distinguished. Subsequently, categories describing similar

strategies were ordered into 11 groups. As a last step in this phase,

these groups were clustered according to the competences

mentioned in the Wubbels, den Brok, et al. (2006) study that they

related to: Monitoring and managing student behaviour, Creating

positive teacher-students relationships, and Teaching for student

attention and engagement.

In the third coding phase, all 611 statements were again

considered and coded for reference by the teacher to the cultural or

ethnic background of students. We identied 60 such statements.

After coding, all statements were summarized and displayed in

cross-case displays (Miles & Huberman, 1994), with the teachers in

the rows and the 30 specic strategies in the columns. In this

display, the strategies were grouped according to the (groups of)

categories to which they belonged. These displays were used to

identify differences and similarities in the statements of the 12

teachers.

Finally, we calculated the relative frequency of mentioning

a specic strategy by dividing the absolute frequency through the

total number of statements of that teacher. Subsequently we

compared the differences in these relative frequencies between

directive, authoritative and tolerant-authoritative teachers, the

subjects they teach, their experiences and the four schools.

3. Results

In this section, we rst describe shared elements in the practical

knowledge of the teachers we interviewed. Then, we discuss the

teachers statements about the cultural and ethnic background of

their students. In our description of the results of the analyses of

the interviews, we illustrate classroom management strategies that

were mentioned by the majority of the 12 teachers with quotes.

Finally, we present the results of the analyses of the differences

among the teachers.

3.1. Practical knowledge about classroom management strategies

Table 2 presents the 30 specic strategies (third column), 11

groups of strategies (second column) and the three competencies

(rst column), together with the number of teachers that

mentioned a strategy and how often the strategy was mentioned.

All 12 teachers talked most about monitoring and managing

student behaviour: 230 of the 332 statements. The teachers talked

far less about creating positive teacherstudent relationships. Three

teachers didnt talk about this at all. Nine teachers did, but not very

frequently: only 30 statements were found on this topic. Eleven of

the 12 teachers talked about teaching for student attention and

engagement: in total there were 72 statements.

We now describe and illustrate the strategies we identied.

3.1.1. Monitoring and managing student behaviour

Almost all teachers talked about being clear about rules and

procedures in the classroom as a condition for creating an orderly

Table 2

Competencies and strategies for classroom management in multicultural classrooms

Competency

Groupings of strategies

Strategies

Monitoring and managing

student behaviour (t12-s230)

Monitor student activities (t5-s12)

Be clear (t12-s73)

1. Monitor student activities (t5-s12)

2. Provide clear rules and procedures (t11-s48)**

3. Teach students the rules (t5-s7)

4. Stick to the rules (t7-s18)

5. Show awareness (t3-s4)**

6. Remind students of the rules (t6-s8)

7. Show anger (t5-s8)

8. Warn (t7-s10)

9. Impose punishment (t9-s18)

10. Use small rather than intense correction (t8-s20)*

11. Sometimes ignore minor misbehaviour (t8-s26)

12. Cope with student emotions (t2-s2)**

13. Use humour to make corrections less grave (t4-s4)

14. Use rational rather than power arguments (t6-s13)**

15. Respond positively to justied criticism (t2-s3)**

16. Adapt approach to student characteristics (t6-s9)

17. Be exible in applying rules (t6-s10)

18. Make rules together with students (t3-s5)

19. Create positive relations to make classroom management easier (t3-s5)**

Put limits to students (t11-s48)*

Prevent escalation (t12-s68)*

Be exible (t6-s19)

Create student commitment (t5-s10)

Creating and maintaining

positive relationships (t9-s30)

Build positive relationships (t7-s19)

Maintain positive relationships (t6-s11)

Teaching for student attention

and engagement (t11-s72)

Use the carrot (t9-s27)

Adapt teaching (t11-s34)

Make content relevant (t6-s11)

20. Use and create opportunities to get to know students (t4-s15)

21. Invest time in building relationships (t3-s4)

22. Show humour (t2-s3)*

23. Give feedback without loss of face or humiliation (t1-s1)*

24. Show respect and give compliments (t 3-s7)*

25. Reward and stimulate (t 6-s14)

26. Frequent and varied testing (t 4-s13)*

27. Adapt pace to individual students needs (t 4-s7)

28. Adapt teaching to expected student response (t10-s27)

29. Probe for students background, beliefs and interests (t3-s5)*

30. Explain the reason for activities (t4-s6)

Competencies have been taken from the earlier Wubbels, den Brok, et al. (2006) study.

In the (tn-sn) behind the label for the strategy, the t refers to the number of teachers that refer to this strategy, s refers to the total number of statements.

Strategies marked with an * were also mentioned in the focus-group interviews reported about in Wubbels, den Brok, et al., 2006, Strategies marked with ** resemble strategies

that were mentioned in these focus-group interviews.

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

457

working climate in the classroom (number of teachers 11, number

of statements 48):

The third is to show that you are irritated or angry (ve teachers,

eight statements).

I have various levels for volume. They know that. Now I said:

No sound, level zero. (Alan)

You have to split up the lessons in parts in such a way that they

know what they can expect.give them clear instructions about

the division of tasks among them, so that they know who should

do what. (Diana)

I want them to remain seated until they hear the bell. If not, they

will start hanging onto the doors and ticking against the

windows and that is something that I dont like. (Tina)

Well, I have said this for three or four times. Then I get irritated.

Then I say: Damn! I have told you this ve times already!

(Daphne)

Especially at the start of the lesson, the rules and procedures are

important for creating an orderly working climate:

If they enter the classroom, there are a number of things that I

denitely want. That they take off their coats and caps and that

their bags are off the table and their books are on the table, so

that I can start right away. (Dave)

I am very strict about that. They have to sit down in a circle and

look at me. For me, that is a condition for starting the lesson.

(Theo)

In this school, you are supposed to write down all the absentees.

At rst I tried to do that while they were still fooling around

a bit. Just have a look around who is present and who isnt. But

that didnt work. You get confrontations among them and all

kinds of behavioural problems. So now I do it this way [read the

students names out loud]. It will cost you a couple of minutes,

but I have to do this to provide them with some structure. If not,

you will have a messy start and that will have its effect on the

rest of the lesson. (Albert)

Teachers also emphasized the importance of sticking to their

own rules (7 teachers, 18 statements):

In this multicultural group.you have to be consistent. You have

less room to negotiate, or give in. That will be used immediately.

(Theo)

Yes, I always react, in a very calm way. I dont let him interrupt

without a reaction. If I didnt, he would think: O, I can do that.

(Alan)

Providing rules and procedures is one thing, the other is to

make students follow these rules. The teachers talked a lot

about this. Not only about putting limits to students (11

teachers, 48 statements), but especially about how to prevent

escalation after correcting students (12 teachers, 68

statements).

Five strategies were mentioned aimed at putting limits to

students, with different levels of severity. The rst one is showing

awareness (three teachers, four statements).

It is ritual really. Put your jacket on the coat-hooks, your bag on

the oor and your books on the table. But there is always at least

one student who does not do that. That one comes in, looks

around, and starts chatting. So you just stand in the front of the

classroom and look. The others will notice this by your way of

looking. You should just go through with this. Keep standing

there and they will notice it and it will be become really quiet.

They notice that I am waiting until their jacket is on the coathooks. Then we can start. (Diana)

The second strategy is to remind students of the rules (six

teachers, eight statements).

This group that was sitting here, with Aisha and Jasmin.. They

talk Turkish. And then I say: Girls, I cant understand you.I

dont want that, you are in the Netherlands here. You should talk

Dutch here.(Thea)

The fourth strategy, aimed at putting limits, to students is

warning students (7 teachers, 10 statements).

He had to come back in and pick up the tray. But he says: I wont

do that. Then I say: Ramazan, come on, pick it up and sit

there! and nally, he does. In this case I dont have to warn him.

But in the end, if it does not work, they get the choice. Either you

pick up the tray and sit down or you can go to the principal and

explain to her why you dont want to pick it up. And that usually

works. (Alan)

The last strategy is to impose punishment (9 teachers, 18

statements).

Well, the rule is that if a mobile phone rings, they have to hand it

in and I will keep it for a while. I have a number of telephones

here! (Tom)

Correcting students can have a negative effect on the classroom atmosphere. The teachers talked even more about how to

prevent escalation after correcting the students (12 teachers, 68

statements) than about how to put limits to students. We

distinguished six strategies. The strategy that the teachers

mentioned most is to sometimes ignore small misbehaviour

(8 teachers, 26 statements):

I dont feel like asking them to be silent each time.At that

moment I thought, Ill just continue. It might take me half an

hour and it wouldnt be silent anyway.I might start a battle

that I wont win. (Thea)

If you have built a relationship with them, you must sometimes

forget things. (Adrian)

The teachers also frequently mentioned using small rather than

intense correction for unwanted student behaviour (8 teachers, 20

statements):

Of course, you can give him a good telling-off. But in this case

just a nonverbal signal was enough. (Dave).

In the past, I have made the mistake of starting to yell at them

and imposing some kind of punishment. But in fact, this only

ruins the atmosphere in the class both for you and for the

students. They suddenly see aggression in front of them. So you

have to nd another solution. Just be silent. After a while they

will start correcting each other and it will become silent.

(Adrian)

3.1.2. Creating and maintaining positive teacherstudent

and peer relationships

The majority of teachers mentioned the importance of building

trustful relations (7 teachers, 19 statements) by using and creating

opportunities to get to know students and invest time in building

relationships. Some examples:

I always try to give them the feeling that I want to pay attention

to them. (Alan)

It [shaking hands with the students when they enter the classroom] works both ways. If you do that, you have their attention

right away and you have a contact that, if it works out right,

remains during the lesson. (Diana)

We have been to the zoo together. We have done all kind of

those things, just because I wanted to get a better grip on them

as group. As a consequence, I had a lot of informal chats with the

students. Of course, that creates a relationship. (Thea)

458

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

3.1.3. Teaching for student attention and engagement

Most teachers talked about taking anticipated student

responses into consideration when they plan their teaching with

the aim to keep their students engaged (10 teachers, 27

statements).

After reading out loud by students, I always read a part myself.

Not because my pronunciation is very good, but because it is

faster and that will keep them or get them involved again.

(Adrian)

They have only worked in groups since the autumn holiday.

Before that, they used to work in pairs. For the kids it is fun and

they like it very much, so I have decided to leave it this way.

(Tina)

Compared to his colleagues one teacher seemed to focus much

more on teaching for student attention and engagement. This

teacher, Tom, talked about teaching for student attention and

engagement twice as much as any other teacher. We scored 17 of

the 49 strategies that he mentioned as strategies that relate to

teaching for student attention and engagement. He was the only

one who referred to testing as a strategy to keep students

attention and keep them engaged more than once. He did this 10

times.

I always explain very clearly that this will count for the exams

and suggest paying attention to this, because here you are able

to score because it is just about your knowledge. (Tom)

This is particularly interesting, because Tom is a very experienced teacher. His interpersonal style was perceived by his

students highest on both teacher inuence and afliation,

compared to the other 11 teachers. Students perceptions of his

style resemble the style that students and teachers, on average,

regard as the ideal style (Wubbels, Brekelmans, et al., 2006). One

of his colleagues refers to his popularity among the students:

Tom also disciplines them. But still, the kids think he is really

great. (Trudy)

3.1.4. Statements about student background

According to Brown (2003), teachers wanting to meet urban

students needs, need to develop an awareness of students

culturally determined communication style. Weinstein et al. (2003)

argue that teachers need to become knowledgeable about the

cultures and communities in which their students live. According to

the teachers in the focus-groups that Wubbels, den Brok, et al.

(2006) interviewed, teachers in multicultural classrooms need to

be aware of, and interested in student diversity, cultural background and personal situation and the consequences of these

characteristics for interactions in the classroom. They also need to

be aware of language difculties.

Table 3 shows that 10 of the 12 teachers in our study did refer to

the students ethnic and cultural background during the videostimulated interviews, although not very frequently. But 7 of these

10 teachers explicitly said that they did not think that ethnic and

cultural differences between students should play a role in their

teaching and communication with the students.

I mean, I am a person myself of course. They can also get used to

how I want it and how I address them. For me, it would go to far

to rst think You are from Turkey and you are from Morocco.

No, that wouldnt work. I take their character into account, but

not their background. (Trudy)

We did have that discussion [about how to cope with cultural

differences between the students]. We dont regard the classes

as multicultural classes. They are just the kids from the neighbourhood. That discussion about the multicultural society and

integration, that is very prominent here of course. But we say:

We do not pay attention to these differences. (Tom)

However, most of these seven teachers seemed to struggle with

whether or not they should pay attention to cultural and ethnic

differences between the students in their classes.

I have thought about it, but I do not notice a big difference

between the students in the classes, whether or not they have

a Turkish background, or have another background. But I do try

to pay attention to their home culture.Last year a new mosque

was built here. We have spoken about it and agreed that it

would be nice to visit it.On the other hand, I think: why? You

should keep the balance; it should not be that this group gets

extra attention. (Tina)

Most teachers made remarks about the challenges of intercultural communication, although not very often (8 teachers, 10

statements).

Then [after a conict with a boy from Moroccan background

about spitting in the corridor] another boy came to me and said:

Miss, he nds it really humiliating that you said this to him in

this way.Then I thought: Hey! This is the rst time that Ive

been confronted with the differences in culture. (Thea)

Only one teacher, Alan, who was born in Surinam and considered his cultural and ethnic background as non-Dutch, talked quite

a lot about the cultural and ethnic differences between the

students. He not only discussed the challenges of intercultural

communication but he is also the only one who referred to the

position of minority groups in Dutch society.

Because, look, these children are in a real Dutch culture at

school, and at home, very often, in the other culture.If, for

instance, you ask a Moroccan child Look at me, you are really

asking him: Be rude to me. Because that is something that this

Table 3

Statements about students ethnic and cultural background

Statement

Groupings of statements

about student background and

Statements

About students ethnic and

cultural background (t10-s60)

Teacher-student

communication (t10-s29)

1. About the role ethnic and/or cultural differences should play when dealing with students (t7-s14)

2. About intercultural communication (t5-s10)

3. About paying attention to students background (t3-s5)

4. About the impact of student background on student behaviour (t5-s6)

5. About the importance of student background for making friends (t5-s7)

6. About language problems for Dutch as second language speakers (t3-s5)

7. About the importance of speaking Dutch in the school premises (t3-s7)

8. About how students with a non-Dutch background talk and think about themselves as members

of the Dutch society (t1-s6)

Student behaviour (t7-s13)

Language (t5-s12)

Their position

in society (t1-s6)

In the (tn-sn) behind the label for the statement, the t refers to the number of teachers that refer to this statements, s refers to the total number of statements.

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

child is not allowed to do at home. If you know that, you know

that you should handle this in another way. (Alan)

The stories are negative.I try to counter this kind of story. In

other words: I tell them that many Moroccan boys make

mistakes, but also that many Dutch young people make

mistakes too. I use myself as an example. If I enter a room and

start yelling at people, everybody knows and will remember

that it was me.but if a white person does that, no one will

recognize him. (Alan)

3.1.5. Differences between groups of teachers

We compared relative frequencies of strategies and practical

knowledge about students background across groups of teachers,

using analysis of variance and correlational analysis. No signicant

differences were found for the interpersonal style of the teachers,

their subject, their experience, or the school at which they teach

(P < 0.05, corrected for the number of analyses using the Bonferroni

method, cf. Bland & Altman, 1995). The relative frequencies of

statements about student background did not differ between

teachers either. The only signicant correlation (0.77) we found,

was between class composition and the number of statements

about the role that ethnic and cultural differences should play

when dealing with students: the more students with a nonwestern background were present in their class, the less teachers

talked about taking the students background into consideration.

4. Conclusions and discussion

The research described in this article wanted to answer the

question: Which elements of practical knowledge underlying

classroom management strategies, are shared by teachers who are

successful in creating a positive working atmosphere in their

multicultural classroom? The identied shared elements of practical knowledge may contribute to the knowledge base about

classroom management in multicultural classrooms.

In the video-stimulated interviews, most statements of the

teachers referred to the importance of providing and enforcing

clear procedures and sound rules, and how to do this in such a way

that no escalation occurs with negative consequences for the

classroom climate. This issue resembles the third theme that

Evertson and Weinstein (2006a) distinguish in classroom

management research: how classroom management strategies

relying on punishment and external reward may negatively inuence the classroom atmosphere. Although the teachers in our study

sometimes ignored disruptive behaviour if they thought that correcting this behaviour would cause rather than solve problems,

they realized that correcting student behaviour can be necessary.

They favoured using small rather than intense corrections and

preferred rational rather than power arguments. The teachers were

aware that corrections that are perceived by students as aggressive

can easily elicit aggressive reactions, whereas small corrections

minimize the risk of introducing aggression. They also realized that

positive feedback and a positive trustful relationship usually elicit

positive student responses. It can be concluded that, according to

these teachers, setting rules and enforcing them is necessary, but it

should be done in a way that is as unaggressive as possible.

The teachers did talk about strategies aimed at promoting

student attention and engagement, but far less than about strategies aimed at setting and enforcing rules. However, Tom, the

teacher who was most successful in creating a positive working

atmosphere in his classroom, talks far more about how he tries to

stimulate student attention and engagement than the other

teachers. This suggests that engaging curriculum and learning

activities work as a proactive approach to preventing problems

459

with discipline, which has positive consequences for creating and

maintaining a positive working atmosphere in the classroom.

The rst theme in classroom management research that Evertson and Weinstein distinguish is the importance of positive

teacherstudents relationship. The teachers in our study did talk

about this, but, again, far less than about providing and enforcing

clear rules. It is remarkable that when they talked about building

positive relationships, they often gave examples of strategies before

the start of the actual lesson, such as handshakes when the

students enter the class or friendly talks before instruction starts, or

of going on trips with the students. It can be hypothesized that

these informal situations before the start of the actual lesson or

even outside the classroom, are particularly important for building

positive relations with students. If this hypothesis would be

conrmed, the relative low frequency of statements relating to

building and maintaining positive relations with the students could

be ascribed to our interview technique, which might stimulate

teachers to comment on their teaching during the formal lesson.

The second theme that Evertson and Weinstein distinguish is

classroom management as a social and moral curriculum. In the

interviews, the teachers hardly talked about their classroom

management strategies from this perspective. However, because all

aspects of teaching have moral implications, these teachers,

classroom management strategies can also be discussed as an

implicit moral curriculum (Fallona & Richardson, 2006). All 12

teachers tend to an orientation to classroom management in which

the teacher is the authority, rules are to be obeyed, and infractions

are to be punished. This orientation is referred to as traditional or

custodial in research summarized by Woolfolk-Hoy and Weinstein (2006). But obey the teacher as the authority is not the only

moral message the teachers communicate to their students. Many

of the strategies that the teachers mention tend to a more liberal

orientation. Examples are the strategies 14 (Use rational rather than

power arguments), 15 (Respond positively to justied criticism), 18

(Make rules together with the students) and 24 (Show respect and give

compliments). In their teaching, these teachers do not only focus on

adherence to the rules, but also on mutual respect in the classroom.

They do not only impose rules, but also discuss them.

The last theme in the research on classroom management that

Evertson and Weinstein distinguish is how teachers take students

background characteristics into account in their classroom

management. Contrary to the teachers in multicultural schools in

the USA (Brown, 2003), the majority of the 12 teachers in our study

in the Netherlands seemed to consider explicit reference to the

cultural and ethnic differences between their students inappropriate when discussing their classroom management strategies. We

even found that the higher the percentage of students with a nonwestern background in their class, the less teachers talked about the

role ethnic and cultural differences should play when dealing with

students. These Dutch teachers present themselves as colour blind

(c.f. Cochran-Smith, 1995; Johnson, 2002; Milner, 2006; Norberg,

2000). This may be attributed to the dominant discourse in Dutch

society, in which it is considered inappropriate to take peoples

ethnic and cultural background into consideration when discussing

their behaviour because this might reinforce prejudice. This seems

to be different from the dominant discourse in the USA-literature in

which teachers are advised to develop an awareness of and

explicitly respond to their [students] ethnic, cultural, social,

emotional and cognitive characteristics (Brown, 2003: 282). A

notable exception among the 12 teachers in our study was Alan. Alan

was the only teacher involved in our research with a non-Dutch

background. He was very much aware of the differences in common

communication styles of mainstream teachers and minority

students and he explicitly tried to help his students nd their way as

members of a minority group in Dutch society. By doing so, his

teaching was in line with the advice of Weinstein et al. (2003) that

460

J. van Tartwijk et al. / Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2009) 453460

teachers should become knowledgeable about the cultures and

communities in which their students live, but they should, at the

same time, teach students mainstream ways to interact so that

students can use these to succeed in dominant social spheres.

In this study, we used video-stimulated interviews conducted

immediately after the lesson with teachers who successfully

created and maintained a positive working atmosphere in their

classrooms. This resulted in a renement of the descriptions of

teacher knowledge about classroom management strategies by,

for instance, Brown (2003), who used interviews, and by Wubbels,

den Brok, et al. (2006), who used focus-group interviews. It can be

hypothesized that using such video-stimulated interviews or

stimulated-recall interviews (Yinger, 1986) is a more effective

data-gathering strategy than regular interviews or focus-group

interviews, in eliciting practical knowledge about classroom

management strategies that guide actual teacher behaviour in the

classroom, because teachers are stimulated to talk about all their

behaviour visible on video and have to rely less on their memory

about what they did in their class.

Still, only investigating teachers statements is probably not

enough to nd out what teachers actually do in classrooms. Further

research is needed to investigate all the strategies teachers actually

use. This is, for instance, important when investigating how

teachers take students background characteristics into account in

their classroom management. The strategies that teachers in the

USA and in the Netherlands use may not differ so much as the way

in which they talk about these strategies.

Finally, further research is needed to investigate the strategies

that teachers use to develop positive relationships with their

students from various cultural and ethnic backgrounds outside the

context of the formal lesson, or even outside the classroom.

References

Banks, J. A. (2004). Multicultural education: historical development, dimensions,

and practice. In J. A. Banks, & C. McGee Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on

multicultural education (pp. 329). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Banks, J. A., & McGee Banks, C. (2004). Handbook of research on multicultural

education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ben-Peretz, M., Eilam, B., & Yankelevitch, E. (2006). Classroom management in

multicultural classrooms in an immigrant country: the case of Israel. In

C. M. Evertson, & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management:

research, practice, and contemporary issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates. pp. 11211139.

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1995). Multiple signicance tests: the Bonferroni

method. Bristish Medical Journal, 310, 170.

Brekelmans, M., Levy, J., & Rodriguez, R. (1993). A typology of teacher communication style. In T. Wubbels, & J. Levy (Eds.), Do you know what you look like?

Interpersonal relations in education (pp. 4655). London: The Falmer Press.

Brophy, J. E., & McCaslin, M. (1992). Teachers reports about of how teachers perceive

and cope with problem students. Elementary School Journal, 93(1), 268.

Brown, D. F. (2003). Urban teachers use of culturally responsive management

strategies. Theory into Practice, 42(4), 277282.

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. (2007). StatLine, 2007 [Data le]. Available at

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek web site <http://statline.cbs.nl>.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Creating grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative

analysis. London: Sage.

Cochran-Smith, M. (1995). Color blindness and basket making are not the answers:

confronting the dilemmas of race, culture, and language diversity in teacher

education. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 493522.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice:

teacher learning in communities. Review of Research in Education, 24,

249305.

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (2006a). Classroom management as a eld of

inquiry. In C. M. Evertson, & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom

management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 316). Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (Eds.). (2006b). Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fallona, C., & Richardson, V. (2006). Classroom management as a moral activity. In

C. M. Evertson, & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management:

Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 10411062). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Johnson, L. (2002). My eyes have been opened: White teachers and racial awareness. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 153167.

Meijer, P. (1999). Teachers practical knowledge. Teaching reading comprehension in

secondary teaching. Leiden: Leiden University.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded

sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Milner, H. R. (2006). Classroom management in urban schools. In C. M. Evertson, &

C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice,

and contemporary issues (pp. 491522). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Norberg, K. (2000). Intercultural education and teacher education in Sweden.

Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(4), 511519.

Onderwijsraad. (2006). Waardering voor het leraarschap. [Appreciation for the

teaching profession]. (No. 20060261/860). Den Haag: Onderwijsraad.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1999). Communicating across cultures. New York: The Guildford

Press.

Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54(1), 5167.

Verloop, N., van Driel, J., & Meijer, P. (2001). Teacher knowledge and the

knowledge base of teaching. International Journal of Educational Research,

35(5), 441461.

Weiner, L. (2006). Urban teaching: The essentials (Revised ed.). New York: Teachers

College Press.

Weinstein, C. S. (2003). Classroom management in a diverse society: introduction to

a special issue. Theory into Practice, 42(4), 266268.

Weinstein, C. S., Curran, M., & Tomlinson-Clarke, S. (2003). Culturally responsive

classroom management. Theory into Practice, 42(4), 269276.

Weinstein, C. S., Tomlinson-Clarke, S., & Curran, M. (2004). Toward a conception of

culturally responsive classroom management. Journal of Teacher Education,

55(1), 2538.

Woolfolk-Hoy, A., & Weinstein, C. S. (2006). Student and teacher perspectives on

classroom management. In C. Evertson, & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of

classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 181

219). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., den Brok, P., & van Tartwijk, J. (2006). An interpersonal

perspective on classroom management in secondary classrooms in the Netherlands. In C. Evertson, & C. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 11611191). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wubbels, T., den Brok, P., Veldman, I., & van Tartwijk, J. (2006). Teacher interpersonal competence for Dutch secondary multicultural classrooms. Teachers and

Teaching: Theory and Practice, 12, 407433.

Wubbels, T., Creton, H. A., & Hooymayers, H. P. (1985). Discipline problems of

beginning teachers, interactional teacher behavior mapped out. Abstracted in

Resources in Education, 20(12), 153.

Wubbels, T., & Levy, J. (1991). A comparison of interpersonal behavior of

Dutch and American teachers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 15, 118.

Yinger, R. J. (1986). Examining thought in action: a theoretical and methodological

critique of research on interactive teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education,

2(3), 263282.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Curriculum and Instruction: Selections from Research to Guide Practice in Middle Grades EducationDe la EverandCurriculum and Instruction: Selections from Research to Guide Practice in Middle Grades EducationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education Studies in Ireland: the Key DisciplinesDe la EverandEducation Studies in Ireland: the Key DisciplinesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article 1Document8 paginiArticle 1Bianca PanchiosuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aprendizaje y Vida 1Document14 paginiAprendizaje y Vida 1electrodescargaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examples of Current Issues in The Multicultural ClassroomDocument5 paginiExamples of Current Issues in The Multicultural ClassroomFardani ArfianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pedagogical Conditions For The Formation of Gender Equality Thinking in StudentsDocument4 paginiPedagogical Conditions For The Formation of Gender Equality Thinking in StudentsAcademic JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teachers Funds of KnowledgeDocument19 paginiTeachers Funds of Knowledgechilenita2013Încă nu există evaluări

- Assessment 1 - Indigenous Learners Culturally Relevant PedagogyDocument6 paginiAssessment 1 - Indigenous Learners Culturally Relevant Pedagogyapi-321018289Încă nu există evaluări

- UnderstandingtheProcessofContextualization FINALDocument23 paginiUnderstandingtheProcessofContextualization FINALJhonalyn Toren-Tizon LongosÎncă nu există evaluări

- PID10529 PrepubDocument27 paginiPID10529 Prepub霍盈杉Încă nu există evaluări

- Writing A Thought PaperDocument18 paginiWriting A Thought PaperEshey Meileah A MarceloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection 1 To 5Document23 paginiReflection 1 To 5Kherl TampayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bonner 2014Document24 paginiBonner 2014Rachel Pearl WulbertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample ProposalDocument7 paginiSample ProposalCharlene PadillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eden Chapter 1Document20 paginiEden Chapter 1Eden MarianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gillies-Nichols2015 Article HowToSupportPrimaryTeachersImp PDFDocument21 paginiGillies-Nichols2015 Article HowToSupportPrimaryTeachersImp PDFBogdan TomaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benavot y Resh Social Cobstruction of Local School CurriculumDocument34 paginiBenavot y Resh Social Cobstruction of Local School CurriculumSoledadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Politics and PedagogyDocument15 paginiPolitics and PedagogyCarolina NavarroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classroom ManagementDocument45 paginiClassroom Managementapi-243098015Încă nu există evaluări

- Langhout and Mitchell - Hidden CurriculuDocument22 paginiLanghout and Mitchell - Hidden CurriculuDiana VillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Vocational Education & TrainingDocument18 paginiJournal of Vocational Education & TrainingIdas MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher's Reflection On PedagogyDocument20 paginiTeacher's Reflection On PedagogyChristian PagayananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Building A Research Agenda For Indigenous Epistemologies and EducationDocument3 paginiBuilding A Research Agenda For Indigenous Epistemologies and EducationCharlie EstevezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culturally Sensitive IS Teaching Lessons Learned TDocument9 paginiCulturally Sensitive IS Teaching Lessons Learned TofeliamunozcatalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teachers' Pedagogy and Conceptions of History: Decolonizing and Transforming History in ElementaryDocument8 paginiTeachers' Pedagogy and Conceptions of History: Decolonizing and Transforming History in ElementarythesijÎncă nu există evaluări

- rtl2 Assignment 2 19025777Document14 paginirtl2 Assignment 2 19025777api-431932152Încă nu există evaluări

- Local Media3179502967958835715Document7 paginiLocal Media3179502967958835715Rhailla NOORÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Representation in Childrens EFL TextbooksDocument7 paginiGender Representation in Childrens EFL TextbooksViolet BeaudelaireÎncă nu există evaluări

- G20-0012 - Philosophy of Philippine EducationDocument35 paginiG20-0012 - Philosophy of Philippine EducationRoxanne Reyes-LorillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bolat 2018Document13 paginiBolat 2018Axell Sutton AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher Education For Inclusion International Literature ReviewDocument6 paginiTeacher Education For Inclusion International Literature ReviewwoeatlrifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Funds of Knowledge and Discourses and Hybrid SpaceDocument10 paginiFunds of Knowledge and Discourses and Hybrid SpaceCris Leona100% (1)

- Waley,,,,stratDocument8 paginiWaley,,,,stratEditha DelacruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self-Regulated Learning - Where We Are TodayDocument13 paginiSelf-Regulated Learning - Where We Are Todayvzzvnumb100% (1)

- Lbs 303 Research PaperDocument10 paginiLbs 303 Research Paperapi-404427385Încă nu există evaluări

- DISCUSSIONSDocument8 paginiDISCUSSIONSEdmar PaguiriganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zhu2013 - Examining School Culture in Flemish and Chinese Primary SchoolsDocument19 paginiZhu2013 - Examining School Culture in Flemish and Chinese Primary SchoolsAlice ChenÎncă nu există evaluări

- 97 Toward A Theory of Thematic CurriculaDocument25 pagini97 Toward A Theory of Thematic CurriculacekicelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of Thematic CurriculaDocument18 paginiTheory of Thematic CurriculaDwight AckermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Review S3 0201622002 HermansyahDocument8 paginiCritical Review S3 0201622002 HermansyahIvan MaulanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Paul C. GorskiDocument10 paginiTeaching and Teacher Education: Paul C. GorskiBri MagsinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching in Higher Education: Is There A Need For Training in Pedagogy in Graduate Degree Programs?Document11 paginiTeaching in Higher Education: Is There A Need For Training in Pedagogy in Graduate Degree Programs?xvlacombeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3502Document28 pagini3502UMSOEÎncă nu există evaluări

- CurriculumDocument4 paginiCurriculumWan Normah Wan Manan100% (1)

- Evaluation Tool For The Application Discovery Teaching Method in The Greek Environmental School ProjectsDocument12 paginiEvaluation Tool For The Application Discovery Teaching Method in The Greek Environmental School ProjectsWardahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Analytics To Understand Cultural Impacts On Technology Enhanced LearningDocument8 paginiLearning Analytics To Understand Cultural Impacts On Technology Enhanced LearningVianey Sánchez FigueroaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science TeachersDocument16 paginiScience TeachersNashwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boring and Stressful or Ideal Learning Spaces Pupils Constructions of Teaching and Learning in Chinese Supplementary SchoolsDocument22 paginiBoring and Stressful or Ideal Learning Spaces Pupils Constructions of Teaching and Learning in Chinese Supplementary SchoolsliuevelynyunheÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Culturally Diverse ClassroomDocument11 paginiThe Culturally Diverse ClassroomDanusa Jeremin100% (1)

- trtr1126 PDFDocument12 paginitrtr1126 PDFNicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Wallace - Leadership and Professional Development in Science Education - New Possibilities For Enhancing Teacher Learning (2003)Document265 paginiJohn Wallace - Leadership and Professional Development in Science Education - New Possibilities For Enhancing Teacher Learning (2003)André FonsecaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educ2420 Final Essay Part 1 CsvilansDocument3 paginiEduc2420 Final Essay Part 1 Csvilansapi-359286252Încă nu există evaluări

- How Will I Get Them To Behave?'': Pre Service Teachers Re Ect On Classroom ManagementDocument14 paginiHow Will I Get Them To Behave?'': Pre Service Teachers Re Ect On Classroom ManagementfatmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definisi AutonomiDocument18 paginiDefinisi AutonomiRichard ColemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- i01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationDocument9 paginii01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationMuhammad Iwan MunandarÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Community of Practice in Teacher Education: Insights and PerceptionsDocument14 paginiA Community of Practice in Teacher Education: Insights and PerceptionscharmaineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophical Perspectives in TeacherDocument12 paginiPhilosophical Perspectives in TeacherDexter GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophical Perspectives in TeacherDocument12 paginiPhilosophical Perspectives in TeacherDexter GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophical and Historical Perspectives On EducationDocument11 paginiPhilosophical and Historical Perspectives On Educationreema yadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self-Perceived Competence, Learning ConceptionsDocument23 paginiSelf-Perceived Competence, Learning Conceptionsmarcus winterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yana Weinstein - Megan Sumeracki - Oliver Caviglioli - Understanding How We Learn - A Visual Guide-Routledge (2018)Document140 paginiYana Weinstein - Megan Sumeracki - Oliver Caviglioli - Understanding How We Learn - A Visual Guide-Routledge (2018)elenamarin1987100% (1)

- Barem Clasa A 10 Sectiunea ADocument1 paginăBarem Clasa A 10 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Ten Steps To Equity in EducationDocument8 paginiTen Steps To Equity in Educationelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1Document23 paginiUnit 1elenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiecte Clasa A 10 Sectiunea ADocument4 paginiSubiecte Clasa A 10 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Barem Clasa A 9 - A - Sectiunea BDocument3 paginiBarem Clasa A 9 - A - Sectiunea Belenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Zelazo EF Implications For Education PDFDocument148 paginiZelazo EF Implications For Education PDFDanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 - Info GraphDocument8 pagini2018 - Info Graphelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea ADocument3 paginiSubiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea ADocument1 paginăSubiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea ADocument3 paginiSubiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A IX A Sectiunea BDocument4 paginiSubiect Clasa A IX A Sectiunea BTololoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A IX A Sectiunea BDocument4 paginiSubiect Clasa A IX A Sectiunea BTololoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea ADocument1 paginăSubiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- UNICEF Learnig Lessons PISA Results Proof 9Document146 paginiUNICEF Learnig Lessons PISA Results Proof 9elenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Progress FOR Children: A Report Card On Immunization Number 3, September 2005Document17 paginiProgress FOR Children: A Report Card On Immunization Number 3, September 2005elenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A XI Sectiunea BDocument4 paginiSubiect Clasa A XI Sectiunea Belenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A X Sectiunea BDocument4 paginiSubiect Clasa A X Sectiunea Belenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea ADocument3 paginiSubiect Clasa A 9 Sectiunea Aelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Subiect Clasa A XII Sectiunea BDocument5 paginiSubiect Clasa A XII Sectiunea Belenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- FOHE-BPRC2 - Final Report - Bucharest ConferenceDocument16 paginiFOHE-BPRC2 - Final Report - Bucharest Conferenceelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- UNICEF Learnig Lessons PISA Results SummaryDocument28 paginiUNICEF Learnig Lessons PISA Results SummaryDiana ChilomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Are Today's General Education Teachers Prepared To Face Inclusion in The Classroom?Document6 paginiAre Today's General Education Teachers Prepared To Face Inclusion in The Classroom?elenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Enabling The Use of Research Evidence WithinDocument21 paginiEnabling The Use of Research Evidence Withinelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Inclusive Classroom Profile (ICP) : A Cultural Validation and Investigation of Its Perceived Usefulness in The Context of The Swedish PreschoolDocument18 paginiInclusive Classroom Profile (ICP) : A Cultural Validation and Investigation of Its Perceived Usefulness in The Context of The Swedish Preschoolelenamarin1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Donna Niday, Jean Boreen, Joe Potts, Mary K. Johnson - Mentoring Beginning Teachers, Second Edition - Guiding, Reflecting, Coaching-Stenhouse Publishers (2009)Document207 paginiDonna Niday, Jean Boreen, Joe Potts, Mary K. Johnson - Mentoring Beginning Teachers, Second Edition - Guiding, Reflecting, Coaching-Stenhouse Publishers (2009)elenamarin1987100% (1)

- 2020 - Rethinking Learning - A Review of Social and Emotional Learning For Education SystemsDocument308 pagini2020 - Rethinking Learning - A Review of Social and Emotional Learning For Education Systemselenamarin1987100% (2)

- Yerevan Communique FinalDocument5 paginiYerevan Communique Finalnicu_boevicuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competente+PARINTI - DRMDocument7 paginiCompetente+PARINTI - DRMalexionctÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching in Focus #19Document6 paginiTeaching in Focus #19Vlad Corina-MariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructor II: Instructor and Course EvaluationsDocument42 paginiInstructor II: Instructor and Course Evaluationsjesus floresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diss Quarter 1 Module 1 For StudentDocument24 paginiDiss Quarter 1 Module 1 For StudentBeverly Anne Eleazar87% (15)

- Trends Summative 3Document3 paginiTrends Summative 3fio jennÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4mat Paper #2 Hope-Focused MarriageDocument9 pagini4mat Paper #2 Hope-Focused Marriagemyyahoo2Încă nu există evaluări

- Measurement Driven InstructionDocument5 paginiMeasurement Driven InstructionDuncan RoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sergiu REDNIC Rezumatul Tezei de Doctoratmanutriff Zoricaeng 2016-08!24!15!36!40Document15 paginiSergiu REDNIC Rezumatul Tezei de Doctoratmanutriff Zoricaeng 2016-08!24!15!36!40kimberly mahinayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enhanced Intervention PosterDocument1 paginăEnhanced Intervention PosterInclusionNorthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivation and Goal SettingDocument4 paginiMotivation and Goal SettingEdher QuintanarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pedagogy HW - HemalataDocument2 paginiPedagogy HW - Hemalataswetha padmanaabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Entrance Exam TEFLDocument5 paginiEntrance Exam TEFLSandro JonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activity StsDocument3 paginiActivity StslittlepreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brit J of Edu Psychol - 2021 - Snijders - Relationship Quality in Higher Education and The Interplay With StudentDocument22 paginiBrit J of Edu Psychol - 2021 - Snijders - Relationship Quality in Higher Education and The Interplay With Studentcharbel_945Încă nu există evaluări

- Sociology: Dr. Ram Mahohar Lohiya National Law UniversityDocument4 paginiSociology: Dr. Ram Mahohar Lohiya National Law University' Devansh Rathi 'Încă nu există evaluări

- Personality and Personal GrowthDocument23 paginiPersonality and Personal GrowthSalima HabeebÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preparing The Emotional and Physical Space: Emotions ChartDocument12 paginiPreparing The Emotional and Physical Space: Emotions Chartzettevasquez8Încă nu există evaluări

- Presentation - 0Document12 paginiPresentation - 0Mvrx XventhÎncă nu există evaluări

- TEST 11th Grade - Compulsive ShoppingDocument3 paginiTEST 11th Grade - Compulsive Shoppingvalentina-serebreanuyandex.ruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investigatory Project BiologyDocument14 paginiInvestigatory Project BiologyF Jackson Kennedy75% (8)

- Organizational BehaviorDocument10 paginiOrganizational BehaviorSean Hanjaya PrasetyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, Research, ApplicationsDocument44 paginiHandbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, Research, ApplicationsElena KuzminaÎncă nu există evaluări

- USYD PSYC 1002 Abnormal Psychology NotesDocument17 paginiUSYD PSYC 1002 Abnormal Psychology NotesYinhongOuyang100% (1)

- Personal Development: InstructionsDocument6 paginiPersonal Development: InstructionsKinect Nueva EcijaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Brand Related Attributes On Purchase Intention ofDocument7 paginiImpact of Brand Related Attributes On Purchase Intention ofxaxif8265Încă nu există evaluări

- 1 JasDocument12 pagini1 JasRaymond LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-4 Learners' Packet in PRACTICAL RESEARCH 1Document33 pagini1-4 Learners' Packet in PRACTICAL RESEARCH 1Janel FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Experimental Study To Assess-5996Document5 paginiAn Experimental Study To Assess-5996Priyanjali SainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Systemic Functional Linguistics: Ideational MeaningsDocument19 paginiSystemic Functional Linguistics: Ideational MeaningsA. TENRY LAWANGEN ASPAT COLLE100% (1)

- Critical ReflectionDocument6 paginiCritical ReflectionFiona LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPL Portfolio Components enDocument9 paginiCPL Portfolio Components enapi-343161223Încă nu există evaluări

- ManagementDocument10 paginiManagementMohammad ImlaqÎncă nu există evaluări