Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Effects of Extrinsic Product Cues On Consumer Perceptions of Quality, Sacrifice and Value

Încărcat de

Dante EdwardsTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Effects of Extrinsic Product Cues On Consumer Perceptions of Quality, Sacrifice and Value

Încărcat de

Dante EdwardsDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

RESEARCH NOTE

The Effects of Extrinsic Product

Cues on Consumers' Perceptions

of Quality, Sacrifice, and Value

R. Kenneth Teas

Sanjeev Agarwal

Iowa State University

The authors report the results of two experiments designed

to test the effects of extrinsic cues--price, brand name,

store name, and country of origin--on consumers'perceptions of quality, sacrifice, and value. The results of the experiments support hypothesized linkages between (a) each

of thefour experimentally manipulated extrinsic cues and

perceived quality, (b) price and perceived sacrifice, (c)

perceived quality and perceived value, and (d) perceived

sacrifice and perceived value. The results also indicate

that the linkages between the extrinsic cues and perceived

value are mediated by perceived quality and sacrifice.

Several researchers have developed and/or tested models of buyers' perceptions of value with particular emphasis on buyers' use of extrinsic cues (such as price and brand

name) as indicators of quality and value ~awar and

Parker 1996; Dodds and Monroe 1985; Erickson and

Johansson 1985; Monroe and Chapman 1987; Monroe and

Krishnan 1985; Stokes 1985; Zeitham11988). On the basis

of a meta-analysis of the results of empirical tests of the

effects of extrinsic cues on consumers' perceptions of

product quality (Rao and Monroe 1989), Dodds, Monroe,

and Grewal (1991) specified a model in which perceived

quality and perceived sacrifice mediate linkages between

(a) brand name, store name, and price and (b) perceived

value. The model is based on two premises. First, conJournal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

Volume 28, No. 2, pages 278-290.

Copyright 9 2000 by Academy of Marketing Science.

sumers' perceptions of value are based on a trade-off

between product benefits (e.g., product quality) and monetary sacrifice. Second, consumers' perceptions of product

quality and monetary sacrifice can be based, at least in

part, on extrinsic cues. Test results reported by Dodds et al.

(1991) suggest that three extrinsic cues (price, brand

name, and store name) are associated with quality and

value perceptions.

This study extends the Dodds et al. (1991) study by

examining linkages specified but not tested in the Dodds et

al. (1991) study (i.e., linkages involving perceived sacrifice) and by examining the degree to which perceived

quality and sacrifice mediate the relationships between the

extrinsic cues and perceived value. In addition, this study

extends the Dodds et al. (1991) model via an additional

extrinsic cue---country of origin. Although the literature

suggests consumers may be influenced by several extrinsic cues beyond those specified by Dodds et al. (1991),

such as warranty (Bearden and Shimp 1982), packaging

(Stokes 1985), and advertising (Milgrom and Roberts

1986), a particularly important extrinsic cue is country of

origin (Chao 1993; Darling and Arnold 1988; Hart and

Terpstra 1988; Hastak and Hong 1991; Johansson, Douglas, and Nonaka 1985; Thorelli, Lim, and Ye 1989; Tse and

Gorn 1993; Wall, Liefeld, and Heslop 1991). Furthermore,

the literature suggests that country of origin may moderate

quality perceptions generated by extrinsic cues (Chao

1993; Erickson, Johansson, and Chao 1984; Hart and Terpstra 1988; Wall et al. 1991). In the following two sections,

the model is developed and the hypotheses are specified.

The third section contains a description of the research

method. The fourth section reports the results of mani-

Teas, Agarwal/ EFFECTS OF EXTRINSIC CUES 279

FIGURE 1

A Conceptual Model of Extrinsic-Cue Effects on

Perceived Quality, Perceived Sacrifice, and Perceived Value

[cor I

Brand

Name

Store

Name

Price

a. Hypothesis6 predictsthat countryof origin willhavea positiveeffecton perceivedquality,and Hypotheses7a-cpredictthat countryof origin willnegatively moderatethe linkages betweenthe other three extrinsic cues (i.e., brand name, store name, and price) and perceivedquality.

pulation checks, measurement validity tests, and tests of

the hypotheses. The fifth section contains discussions of

the findings.

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

The conceptual model examined in this study, which is

diagrammed in Figure 1, suggests that quality and sacrifice

perceptions mediate linkages between (a) antecedents of

consumers' quality and sacrifice perceptions (e.g., brand,

store, and price) and (b) consumers' perceptions of value.

Country of origin is specified as an extrinsic quality cue

and as a moderator variable.

The Impact of Price on Consumers'

Perceptions of Quality and Sacrifice

Considerable theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that price is often used by consumers as an extrinsic

product-quality cue (Bearden and Shimp 1982; Dodds and

Monroe 1985; Dodds et al. 1991; Erickson and Johansson

1985; Lichtenstein, Block, and Black 1988; Lichtenstein,

Ridgway, and Netemeyer 1993; Monroe and Krishnan 1985;

Rao and Monroe 1989; Zeithaml 1988). Theoretical rationales underlying an expected positive price-quality linkage

can be based on expected market forces--high-quality

products often cost more to produce than low-quality

products and competitive pressures limit firms' opportunities to charge high prices for low-quality products (Curry

and Riesz 1988; Erickson and Johansson 1985; Lichtenstein et al. 1993). Complicating the extrinsic cue effect of

price is that price also is an indicator of sacrifice (Dodds et

al. 1991; Erickson and Johansson 1985; Grewal, Monroe,

and Krishnan 1998; Lichtenstein et al. 1993; Zeithaml

1988).

The Impact of Brand and Store on

Consumers' Perceptions of Quality

Research evidence indicates that brand names (Dodds

and Monroe 1985; Stokes 1985) and store names (Wheatley and Chiu 1977) are extrinsic quality cues. Researchers

have viewed brand name as a "summary" construct (Hart

1989; Johansson 1989) or a "shorthand" cue (Zeithaml

1988) for quality because consumers can make product

quality inferences based on brand name. The process can

be explained via the "affect-referral" process discussed by

Wright (1975), which suggests consumers do not examine

brand attributes every time they make brand choice decisions; they simplify their decision-making process by basing their judgments on brand attitudes (summary information) rather than on product attribute information.

Empirical test results reported by Dodds et al. (1991) indicated significant brand and store treatment effects on consumers' perceptions of product quality.

280

JOURNALOF THEACADEMYOFMARKETINGSCIENCE

Country of Origin as an

Additional Extrinsic Quality Cue

The results of several published studies (see Bilkey and

Nes 1982 and Han 1989 for reviews) suggest that country

of origin may directly affect consumer perceptions of

quality and/or may moderate the effects of other product

quality cues.

Main effects. Research results reported by Erickson et al.

(1984) and Johansson et al. (1985) indicate positive relationships between country-of-origin image favorability

and respondents' ratings of automobiles on specific features. Research results reported by Hastak and Hong

(1991) indicate that the impact of country of origin on

quality perceptions can be comparable with that of price,

and research results reported by Darling and Arnold

(1988) suggest that country of origin can be more important than brand name as an influencer of quality perceptions. Thorelli et al. (1989) conducted an experiment to

examine the impact of country-of-origin cue (in conjunction with product warranty and retail-store cues) on perceived quality, overall attitude, and purchase intention.

The results suggest that consumers' perceptions of country

of origin affect their perceptions of quality, attitude, and

purchase intention. Wall et al. (1991) examined the impact

of country-of-origin, price, and brand cues on perceived

product quality, perceived risk associated with purchasing

the product, perceived value, and likelihood of purchasing.

All three cues were found to be significantly related to perceived product quality. Experimental research results by

Tse and Gorn (1993) indicated that country of origin,

brand name, and consumers' experience with the product

resulted in significant main effects on respondents' perceived product quality. Experimental research results reported by Chat (1993) indicated that price, country of

design, and country of assembly were statistically significant predictors of respondents' quality perceptions. Han

and Terpstra (1988) also reported significant main effects

of country of origin and brand name on overall evaluation

of automobiles.

Moderator variable effects. On the basis of the concept

of country-of-origin halo effects (Erickson et al. 1984;

Han 1989; Hanssens and Johansson 1991), Chat (1993)

argues that the effects of extrinsic quality cues such as

price may be different across different countries' products.

He argues that when consumers have high (low) confidence in a country's ability to produce high-quality products, they may perceive that the products produced in the

country will be generally high-quality (low-quality) products; consequently, consumers may be less (more) likely to

use price as an indicator of quality. Empirical findings reported by Chat (1993) suggested that for television sets

manufactured in a high-quality-image country (Japan),

price differentials were not translated into quality image

SPRING2000

differentials. However, for television sets designed in

countries with the lower-quality image (e.g., Taiwan),

higher prices were associated with significantly higherquality ratings. Research also suggests that country of origin may moderate brand name--perceived quality and store

name-perceived quality linkages. Han and Terpstra

(1988) report findings that indicated United States' brands

that were manufactured in the United States were perceived to be of much higher quality than the United States'

brands manufactured in Korea--the country of origin for

the brand moderated the impact of the brand on perceived

quality ratings. Wall et al. (1991) reported similar

country-by-brandinteraction effects in predictions of consumer quality perceptions. In addition, Thorelli et al. (1989)

argue that a high (low)country-of-origin image may enhance (reduce) the impact that store image has on the perceived quality.

Antecedents of Perceived Value

Consumer perceptions of value are posited by Dodds et

al. (1991) to involve a trade-off between perceived quality

and perceived sacrifice that results in a positive linkage

between perceived quality and perceived value and a negative linkage between perceived sacrifice and perceived

value. This conceptualization of value is similar to conceptualizations posited by Hauser and Urban (1986) and

Zeithaml (1988) and suggests (a) perceived quality mediates the linkages between extrinsic cues and perceived

value and (b) perceived sacrifice mediates the linkage

between price and perceived value. Empirical findings

reported by Dodds et al. (1991) indicated strong support

for their hypothesized positive linkage between perceived

quality and perceived value, their hypothesized positive

linkages between two extrinsic cues (i.e., brand and store

name) and perceived value, and their hypothesized negative linkage between price and perceived value.

Hypotheses

This study extends the Dodds et al. (1991) study by examining the role of an additional extrinsic cue---country of

origin--and by testing the degree to which perceived quality and perceived sacrifice mediate the effects of the extrinsic cues on consumers' perceptions of value. It is important

to note that the mediating role of perceived sacrifice was

hypothesized but not tested by Dodds et al. (1991). Furthermore, although the model proposed by Dodds et al.

(1991) implies that the impact of the extrinsic cues on perceived value is mediated via perceived quality and sacrifice, they did not specify formal hypotheses or tests for

mediation they examined relationships between the extrinsic cues and perceived value independent of the impact

of the perceived quality and perceived sacrifice mediating

variables. Our research extends the Dodds et al. (1991)

Teas,Agarwal/ EFFECTSOFEXTRINSICCUES 281

study by examining the impact of the extrinsic cues on perceived value after controlling for perceived quality and

sacrifice. On the basis of the Dodds et al. (1991) model, the

following direct-effect hypotheses are specified:

Hypothesis la: Price level is positively related to perceived quality.

Hypothesis lb: Price level is positively related to perceived sacrifice.

Hypothesis 2: Favorability of the brand name is positively related to perceived quality.

Hypothesis 3: Favorability of the store name is positively

related to perceived quality.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived quality is positively related to

perceived value.

Hypothesis 5: Perceived sacrifice is negatively related to

image favorability and (b) realistic price ranges. The pretest led to the selection of two products (handheld business

calculators and wristwatches), four brand names (Hew,lea

Packard and Royal for calculators and Seiko and Precis for

wristwatches), four retail outlets (Campus Bookstore and

K-Mart for calculators and Belden Jewelers and K-Mart

for wristwatches), four countries of origin (Japan and

Mexico for calculators and Switzerland and Mexico for

wristwatches), and six price levels ($15, $32, and $50 for

calculators and $50, $175, and $300 for wristwatches).

Handheld business calculators (with Hewlett Packard and

Royal brand treatments) were used by Dodds et al. (1991),

thus providing us the opportunity to replicate their study.

Wristwatches were used by MacKenzie and Lutz (1989) in

a study involving a similar participant population.

perceived value.

Sample

On the basis of the empirical evidence that country of origin may be an important extrinsic quality cue, the following hypothesis is specified:

Hypothesis 6: Favorability of the country-of-origin image is positively related to perceived quality.

Hypotheses 1-6 indicate that perceived quality and perceived sacrifice mediate the linkages between the extrinsic

cues and perceived value.

On the basis of the previously cited empirical evidence,

country of origin is also hypothesized to moderate the effects of other extrinsic cues (Chao 1993); hence, the hypotheses are the following:

Hypothesis 7a: Country of origin moderates the pricequality relationship hypothesized in Hypothesis la.

Hypothesis 7b: Country of origin moderates the brand

name--quality relationship hypothesized in Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 7c: Country of origin moderates the store

name--quality relationship hypothesized in Hypothesis 3.

THE EXPERIMENT

Experimental Design

The hypotheses were tested via experiments based on a

2 x 2 x 2 x 3 between-subjects full-factorial design. The

experimental manipulations involved two brand-image

levels (high and low), two store-image levels (high and

low), two country-of-origin image levels (high and low),

and three price levels (high, medium, and low).

A pretest involving 70 university undergraduate students was used to determine (a) the type of products, brand

names, store names, and countries of origin recognizable

to the participants and distinguishable on the basis of

The participants in the experiment consisted of 5301

undergraduate students attending a major midwestern university. Similar to procedures used by Dodds et al. (1991),

students were randomly assigned to 24 treatment cells for

the calculator study. The cell assignments for the wristwatch experiment were also random and independent

from the experimental cell assignments for the calculator

experiment.

The Stimuli and Measures

Data were collected via two questionnaire surveys,

separated by 1 week, that were administered to the same

sample of students. The time lag between the surveys was

planned to reduce carryover effects (note that Dodds et al.

1991 obtained responses for two separate stimuli at the

same time). The product represented in the stimulus advertisement was handheld business calculators in one survey

and wristwatches in the other. The advertisement, which

displayed a black-and-white picture of the product,

remained unchanged across the treatments. The experimentally manipulated brand name, store name, country of

origin, and price information were displayed beside the

picture.

The questionnaires contained measures for the endogenous variables followed by manipulation check measures.

Perceived quality and perceived value were assessed via

five-item scales developed by Dodds et al. (1991). Since

Dodds et al. ( 1991) did not measure perceived sacrifice, a

scale was constructed for this study based on published

discussions of perceived sacrifice (Dodds et al. 1991;

Monroe and Chapman 1987). The following two items

were used to measure perceived sacrifice (5-point

response scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 =

strongly agree): (I) If I purchased the (watch/calculator)

for the indicated price, I would not be able to purchase

some other products I would like to purchase now; and (2)

282

JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE

If I purchased the (watch/calculator) for the indicated

price, I would have to reduce the amount of money I spend

on other things for a while.

Since students possess varying levels of financial

resources, they can be expected to have different perceptions of the degree to which a particular price represents a

sacrifice. Thus, we measured the concept of sacrifice from

a budget constraint perspective. This measure allows for

the possibility that the perception of sacrifice will vary

depending on an individual's financial situation. The same

price may involve a higher level of sacrifice for a financially constrained individual when compared with a financially endowed individual (Schmidt and Spreng 1996).

The manipulation check measures consisted of respondents' perceptions of the brand (7-point scale where 7 =

high quality and 1 = low quality), price (7-point scale

where 7 = very high and 1 = very low), store (three 7-point

scales measuring the likelihood that the store "sells highquality merchandise," "is a prestigious store:' and "is a

high-quality store"), and country of origin (six 5-point

agree~disagree scales involving expectations about the

product's quality, durability, prestige, reliability, workmanship, and dependability).

RESULTS

Preliminary Tests

Manipulation checks. One-way analyses of variance

(ANOVAs) were conducted to assess the impact of the

three price levels (calculators: F2. 527= 135.26, p < .000;

wristwatches: Fz 52~= 127.96, p < .000), the two brand levels (calculators: F1. s28= 592.65, p < .000; wristwatches:

F~.527= 274.78, p < .000), the two store names (calculators:

F~.52s= 118.73, p < .000; wristwatches: F L527= 342.74, p <

.000), and the two countries of origin (calculators: Fl.52s=

238.60, p < .000; wristwatches: F~. s27= 460.52, p < .000).

Each of the manipulation checks indicated that the four

extrinsic-cue experimental treatments were perceived by

the respondents as intended. For the calculators, Hewlett

Packard received more favorable brand-image ratings than

Royal; Campus Bookstore received more favorable storeimage ratings than K-Mart; Japan received more favorable

country-image ratings than Mexico; and $50, $32, and $15

were considered by the respondents to represent high, medium, and low prices, respectively. For the wristwatches,

Seiko received more favorable brand-image ratings than

Precis; Belden Jewelers received more favorable storeimage ratings than K-Mart; Switzerland received more favorable country-image ratings than Mexico; and $300,

$175, and $50 were considered by the respondents to be

high, medium, and low prices, respectively.

SPRING 2000

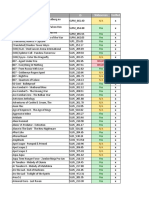

TABLE 1

Factor Analysis Results

Watch Data

Item

Factor Factor Factor Factor Factor Factor

1

2

3

1

2

3

Quality perception

Reliability

.85

Workmanship

.86

Quality

.90

Dependability

.90

Durability

.74

Value perception

Value for money

.42

Economical

.09

A good buy

.32

An acceptable price ,22

A bargain

.03

Sacrifice perception

. . . unable to purchase some other

products I would

like to purchase

now.

-. 11

. . . reduce the

amount of money

I spend on other

things for a while. -. 11

Eigenvalue

Percentage of

variance

explained

Calculator Data

.18

.12

.14

.19

.25

-.10

-.09

-.06

-.03

-.08

.91

.90

.93

.94

.85

.12

.18

.16

.13

.22

-.01

.02

.03

.02

.04

.69

.87

,86

.85

.79

.05

.18

.09

.19

.16

.39

.07

,33

,13

.06

.77

.88

.85

.91

.86

.06

-.24

-.I0

-.17

-.19

.18

.86

.04

-.21

-.91

.24

.87

.04

-.25

.90

5.57

3.06

1.17

5.84

3.09

1.19

46.40

25.50

9.80 48.60 25.80

9.90

Preliminary assessment of the measures. Following the

procedures used by Dodds et al. (1991), we assessed the

measures of perceived quality, value, and sacrifice via factor analysis by using varimax rotation, Cronbach's alpha,

and correlation analysis. The results of the factor analyses,

which are reported in Table 1, indicate three factors that

are consistent with the intended measures and that account

for more than 80 percent of the variance in the two sets of

data. 2 Coefficients alpha for the quality, sacrifice, and

value measures are .94, .89, and .93, respectively, for the

wristwatch data and .96, .85, and .94, respectively, for the

calculator data. Average interitem correlations for the

quality, sacrifice, and value measures are .75, .81, and .72,

respectively, for the wristwatch data and .81, .75, and .74,

respectively, for the calculator data.

Preliminary MANOVA Tests

Before examining specific hypothesized linkages, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to test

the hypothesized linkages between the set of treatment

variables and the set of endogenous variables. The results

Teas, Agarwal / EFFECTS OF EXTRINSIC CUES 283

TABLE 2

Analysis of Variance and Covariance (wristwatch data)

MANOVA

Treatment

Wilks

Brand (B)

Country (C)

Store (S)

Price (P)

Bx C

SxC

P C

Bx S

Bx P

Sx P

.933

.898

.928

.637

.989

.984

.988

.977

.980

.997

df

3; 512

3; 512

3; 512

6; 1024

3; 512

3; 512

6; 1024

3; 512

6; 1024

6; 1024

ANOVA

F Value

Quality

F Value

12.29"**

19.43"**

13.19"**

43.22***

1.85

2.81'

1.01

4.07**

1.74

.22

21.09"**

56.56***

20.57***

5.57**

1.04

.69

.17

5.70*

1.61

.01

Sacrifice

F Value

2.33

.04

.43

43.03***

.65

1.65

1.57

2.95

2.43

.40

ANCOVA

Value

F Value

26.53***

18.58"**

35.12'**

84.18"**

.98

7.76**

1.66

8.35**

2.00

.32

Covariates

Quality

Sacrifice

Mean square explained

Mean square residual

F

13.28

1.52

8.74***

8.69

1.17

7.43

29.28

1.50

19.52

Value

F Valuea

Value

F Valueb

Value

F Valuec

14.32"**

.64

16.87"**

85.19"**

3.63

5.78*

1.27

2.42

1.06

.27

11.63"**

1.11

18.37"**

125.54"**

2.55

7.29**

1.59

4.14"

.91

.42

30.20***

18.85"**

34.77***

56.54***

1.32

6.70**

1.45

6.83**

2.08

.23

148.27"**

37.58***

123.80"**

37.66

1.13

33.33

17.05"**

37.33

1.21

30.85

28.98

1.46

19.85

NOTE: MANOVA = multivariate analysis of variance; ANOVA= analysis of variance; ANCOVA= analysis of covariance.

a. Covariates = quality and sacrifice.

b. Covariate = quality.

c. Covariatc = sacrifice.

*Significant at .05. **Significant at .01. ***Significantat .001.

of the analyses of the wristwatch data, which are reported

in Table 2, indicate that each of the extrinsic-cue variables

is significantly related to the set of dependent variables.

These results indicate that testing specific hypothesized

linkages specified in Figure 1 is justified. In addition, the

store-by-country (S x C) and the brand-by-store (B x S)

interactions are significant. The results of the analyses of

the calculator data, which are reported in Table 3, indicate

that three of the four extrinsic cues are significantly related

to the set of endogenous variables. These results indicate

that testing specific hypothesized linkages specified in

Figure 1 is justified. However, none of the two-way interaction terms were significant at the .05 level.

The univariate homogeneity of variance across the 24

groups was assessed via the Bartlett-Box test. The results,

based on the wristwatch data, were nonsignificant for

quality (p = .488) and value (p = .116) but significant for

sacrifice (p = .002). The results, based on the calculator

data, were nonsignificant for quality (p = .206) and sacrifice (p = .639) but significant for value (p = .024). Multivariate tests of homogeneity of covariance matrices using

the wristwatch data and calculator data were statistically

significant (Box's M = 195.28, p = .01) and statistically

insignificant (Box's M = 173.85, p = .06), respectively. It is

important to note, however, that violation of the equality of

variance-covariance matrices assumption has minimal

impact if the groups are of approximately equal size (Hair,

Anderson, Tatham, and Black 1995:275).

Hypotheses Tests Involving the

Prediction of Perceived Quality

and Perceived Sacrifice

The hypotheses focusing on the prediction of perceived

quality and perceived sacrifice were tested via ANOVA

procedures.

Price. T h e results for the wristwatch experiment (Table 2)

indicate that the price-level manipulation_positively affected perceived quality (Xt, p~ = 4.47 vs. X . ~ , m ~ = 4.72

vs. Xh~r~ = 4.95; Fz52s= 5 . 5 7 , p < .01) and perceived sacrifice (X~o,p~ = 3.35 vs. Xm~i,~,~ = 4.18 vs. X ~ r ~ = 4.36;

/72. 52s = 43.03, p < .001). Similarly, the results for the experiment involving calculators (Table 3) indicate that the

price-level manipulation p__ositively affected p.e.rceived

quality (Xj, r ~ = 4.75 vs. Xm~i r ~ = 4.98 VS. ~ ~.~ =

5.10; F2.52__9= 3.24, p < .05) and_perceived sacrifice (Xk,,p,~ =

2.21 VS. X~d~mp,~ = 3.09 VS. Xh~jh~ = 3.58; F2.s29= 74.55,

p < .001). Thus, the relationships between price and perceived quality and sacrifice proposed in Hypothesis 1a and

Hypothesis lb are supported in both experiments.

B r a n d . T h e results for the wristwatch experiment (Table 2) indicate a significant effect of brand name on perceived quality, F(1, 528) = 21.09, p < .001. Since the

brand-by-store interaction 3 is statistically significant, the

brand effect is interpreted within store levels. The brand

effect is significant within the low-store condition but is

284

JOURNALOF THE ACADEMYOF MARKETINGSCIENCE

SPRING 2000

TABLE 3

Analysis of Variance and Covariance (calculator data)

MANOVA

Treatment

Wilks

Brand (B)

Country (C)

Store (S)

Price (P)

Bx C

Sx C

Px C

BxS

Bx P

SxP

.897

.865

.996

.627

.991

.996

.977

.996

.984

.992

df

3; 513

3:513

3; 513

6; 1026

3; 513

3; 513

6; 1026

3; 513

6; 1026

6; 1026

ANOVA

F Value

Quality

F Value

19.74'**

26.76***

.77***

45.04***

1.54

.73

2.03

.65

1.36

.72

59.36***

76.96***

.43

3.24*

2.39

.05

1.94

1.60

1.08

.60

Sacrifice

F Value

.10

1.40

1.55

74.55***

1.70

.32

1.85

.28

2.88

.92

ANCOVA

Value

F Value

12.49'**

18.80"**

.19

74.34***

2.78

1.48

2.88

.15

.31

1.25

Covariates

Quality

Sacrifice

Mean square explained

Mean square residual

F

18.23

1.64

11.12

13.66

1.16

11.78

23.90

1.73

13.82

Value

F Valuea

Value

F Valueb

Value

F Valuec

.07

.93

.26

56.40***

.72

1.82

2.35

.00

.12

.66

.06

.36

.63

106.40'**

1.23

2.10

3.22*

.03

.44

.99

12.63"**

22.29***

.03

36.10'**

1.97

1.24

2.01

.27

.06

.93

115.76"**

28.98***

115.22'**

--

33.57

1.35

24.87

33.21

1.42

23.39

28.37***

25.42

1.65

15.41

NOTE: MANOVA= multivariate analysis of variance; ANOVA= analysis of variance; ANCOVA= analysis of covariance.

a. Covariates = quality and sacrifice.

b. Covariate = quality.

c. Covariate = sacrifice.

*Significant at .05. **Significantat .01. ***Significantat .001.

insignificant within the high-store condition (high store:

X~ow~,d._y3.75 vs. Xh~ ~,~d= 3.98; F~.~ = 2.40,p <. 123; low

store: X~o,b,~,d= 2.99 VS. X~ghb~,~d= 3.74; F~.563= 20.38, p <

.000). These findings indicate that the relationship between brand name and perceived quality hypothesized in

Hypothesis 2 is supported under the low-store condition

but is not supported under the high-store condition. The resuits for the calculator experiment (Table 3) indicate a significant effect of brand name on perceived quality (X~o~,,~ =

4.48 vs. X~h b,~d= 5.39; F1.559 -- 59.36, p < .001); therefore,

Hypothesis 2 is supported. Note that the brand name treatment has no significant effect on perceived sacrifice in either experiment as expected.

Store. The results for the wristwatch experiment (Table 2)

indicate a significant effect of store name on perceived

quality, F(1,528) = 20.57,p < .001. The store treatment effects were interpreted within brand treatment levels

(brand-by-store interaction is significant). The store treatment effect is significant within the low-brand condition

but is insignificant in the high-brand condition (high

brand: Xio,,to~ = 3.74 vs. Xhi~ ~ = 3.98; Fi. 5~ = 3.37, p <

.125; low brand: Xjow~ = 2.99 vs. Xh~gh~o~= 3.75; F~. 561=

21.04, p < .000). 4Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported under the low-brand condition but is not supported under the

high-brand condition. However, the results for the calcula-

tor experiment (Table 3) indicate that the store name treatment has no significant effect on consumers' perception of

quality; thus, Hypothesis 3 is not supported in the experiment involving calculators. Note that the store name treatment has no significant effect on perceived sacrifice in

either experiment as expected.

Country o f origin. The results for the experiment involving wristwatches (Table 2) indicateasignificant effect

o f country name on perceived quality (X,...... ~ = 4.31 vs.

Xh~h~n~ = 5.13 ; F1.558= 56.5 6, p <.001). In addition, the resuits for the experiment involving calculators (Table 3) indicate a significant e f f e c t o f country name on perceived

quality (X,o~m~ = 4.46 VS. X~'~con,~r= 5.41; F1.559= 76.96, p <

.001). Thus, Hypothesis 6 is supported in both experiments. Note that the country name treatment has no significant effect on perceived sacrifice in either experiment

as expected.

Moderating effects o f country o f origin. The results for

the experiments involving wristwatches (reported in Table 2) and calculators (reported in Table 3) indicate that

none of the second-order interaction terms involving

country of origin have a significant effect on perceived

quality. Thus, the results of both experiments do not support Hypotheses 7a-c.

Teas, Agarwal/ EFFECTSOF EXTRINSICCUES 285

Hypotheses Teats Involving the

Prediction of Perceived Value

The hypotheses involving the prediction of perceived

value, and the associated mediation effects, were tested via

ANOVA and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) following

Baker, Grewal, and Parasuraman (1994) and Grewal et al.

(1998). Three conditions must be met to establish mediation: (1) the independent variables affect the mediator; (2)

the independent variables affect the dependent variable;

and (3) when the independent variables and the mediators

are regressed on the dependent variable, the mediators are

significant and the effects of the independent variables are

reduced (Grewal et al. 1998).

The ANOVA results presented in the previous section

satisfy the first condition, except for the insignificant store

effect in the calculator experiment. The second condition

was tested via ANOVA in which the dependent variable is

perceived value and the independent variables are the four

extrinsic cues. The results involving wristwatches (Table 2)

indicate that each of the extrinsic cues is significant (p <

.001). In addition, two interaction effects (S x C and B x S)

are significant (p < .01). The results of the calculator

experiment (Table 3) indicate that three of the four extrinsic cues--brand, country, and price--are significant. With

the exception of the insignificant store effect in the calculator experiment, these results satisfy the second condition

needed to establish a mediation effect.

ANCOVA was used to assess the third condition for

mediation. The results of the wristwatch experiment

(Table 2), which indicate that perceived quality and sacrifice are significant (F = 148.27, p < .001 and F = 37.58, p <

.001, respectively), support Hypotheses 4 and 5. In addition, price, brand, and store are significant (p < .001) and

the brand-by-store interaction is significant (p < .05). The

results of the calculator experiment (Table 3), which indicate that perceived quality and sacrifice are significant (F =

115.76, p < .001 and F = 28.98, p < .001, respectively),

support Hypotheses 4 and 5. Furthermore, price is a significant predictor in the estimate. Since the F values associated with the direct effects of the extrinsic cues on perceived value are generally smaller in the presence of the

covariates than in their absence, these findings largely satisfy the third condition for mediation.

DISCUSSION

Price as a Quality and Sacrifice Cue

Similar to the empirical results reported by Dodds et al.

(1991), the findings support the hypothesized positive

linkage between price and perceived quality. Also, the

findings extend the Dodds et al. (1991) empirical results

by testing the price-perceived sacrifice linkage hypothe-

sized but not empirically tested by Dodds et al. (1991 ) and

by demonstrating that price continues to be a significant

quality cue in the presence of other extrinsic quality cues,

including country of origin.

Brand, Store, and Country

of Origin as Quality Cues

Similar to the results reported by Dodds et al. (1991),

the findings indicate that the brand treatment is a statistically significant quality cue in the presence of a price cue

and that this effect continues to be significant in the presence of a store quality cue. In addition, the results indicate

that the effect of brand treatment is significant in the presence of the country-of-origin cue. This suggests that, when

the other quality cues are controlled or held constant,

brand can affect consumers' perceptions of product quality. It should be noted, however, that the brand treatment

administered in this study did not significantly affect

wristwatch quality perceptions in the context of a high

store image. Similarly, the findings involving wristwatches indicate the retail name treatment is a significant

quality cue in the context of a low brand image but is insignificant in the context of a high brand image. In general,

the pattern of results concerning the store-by-brand interaction effect indicates that the effect of one cue on wristwatch quality perceptions is stronger when the other cue is

weak, which suggests perceived quality and value can be

enhanced by improving brand image o r by distributing

through high-image stores. The findings indicate the retail

store is not a significant quality cue in the calculator

experiment.

The country-of-origin cue was found to have a significant main effect on the perceived quality for both of the

products examined. However, the findings do not support

the hypothesized effects of country of origin as a moderator variable. A possible explanation for this finding is that

the brands and stores used in this study have somewhat

unambiguous images; consequently, the brand and store

main effects are stable across situation (e.g., country-oforigin condition). The respondents may have perceived

that wristwatches and calculators are routinely manufactured in many different countries using standardized

manufacturing and quality control procedures. Moreover,

with the trend toward increased globalization of business,

Seiko watches made in Mexico may be perceived by consumers to be made by Seiko, or at least under the control or

supervision of Seiko, rather than by a Mexican manufacturer without the control or supervision of Seiko. Consequently, the brand effect on perceived quality is not moderated by country of origin. Furthermore, if these kinds of

products are perceived by consumers to be routinely

manufactured in different countries, the effects of price

and store as quality cues may be unaffected by country of

origin as suggested by our findings.

286

JOURNALOF THE ACADEMYOF MARKETINGSCIENCE

Perceived Quality and Sacrifice

as Predictors of Perceived Value

The results support the hypothesized linkages between

the perceived quality and perceived value and between

perceived sacrifice and perceived value. These findings

extend the Dodds et al. (1991) findings in that perceived

sacrifice is found to be a significant predictor of perceived

value.

The results indicate that the effects of the extrinsic

product cues--price, brand, store, and country of origin---on perceived value are mediated by perceived quality and sacrifice. First, the findings of the wristwatch

experiment indicate that the extrinsic cues have significant

direct linkages with perceived quality, which, in turn, has a

significant positive linkage with perceived value. However, the findings indicate that three extrinsic cues-brand, store, and price--have significant direct linkages

with perceived value that are not completely mediated by

perceived quality and/or perceived sacrifice. Second, similar to the findings of the wristwatch experiment, the findings of the calculator experiment indicate a direct linkage

between price and perceived value in addition to indirect

linkages mediated by perceived quality and sacrifice.

These findings suggest the price-value relationship is

complex--price has positive linkages with perceived sacrifice and perceived quality, which, in turn, have negative

and positive relationships, respectively, with perceived

value. The ultimate effect of a price decision in a particular

situation is affected by the relative strengths of these sets

of linkages.

Effect Size

Table 4 contains a comparison of effect sizes reported

by Dodds et al. (1991) with effect sizes estimated in this

study.

Price. As indicated in Table 4, the effect size of price on

perceived quality is smaller in the current study under the

four-cue condition (rl 2= .015) than the effect size resulting

from the Dodds et al. (1991) three-cue condition (rl 2 =

.030). This supports the Dodds et al. (1991) findings that

the effect of price on perceived quality tends to be reduced

in the presence of additional extrinsic cues. However, a

comparison of our findings with Dodds et al. (1991) findings does not indicate that the effect of price on perceived

value is smaller under the four-cue condition than it is under the three-cue condition.

Brand. The effect sizes of brand on both perceived

quality (rl 2 = .065) and perceived value (rl 2 = .025) are

smaller in the current study under the four-cue condition

than the effect sizes resulting from the Dodds et al. (1991)

three-cue condition.

SPRING2000

TABLE 4

Average Main Effects of Independent Variables:

Dodds, Monroe, and Grewal (1991) Compared

With the Current Study

Combined Effect Size (1]2)

Independent

Perceived Perceived Perceived

Variable TreatmentConditiona Quality Sacrifice Value

Price

Withbrandand store

(DMG91)

Price

Withbrand,store,

and country(Coo)

Brand

Withpriceand store

(DMG91)

Brand

Withprice, store,and

country(Coo)

Store

Withprice and brand

(DMG91)

Store

Withprice,brand,and

country(C~176

Country Withprice,brand, and

store (C~176

.030

NA

.195

.015

.180

.210

.295

NAt

.090

.065

.005

.025

.015

NA

.010

.020

.000

.020

.105

.000

.030

NOTE:NA = not applicable.

a. DMG9~designatesfindingsfromDodds,Monroe,and Grewal(1991);

C~ designatesfindingsfromthe currentstudy.

Store. The effect sizes of store on perceived quality

(112= .020) and perceived value (rl 2= .020) are not smaller

in the current study under the four-cue condition than the

effect sizes resulting from the Dodds et al. (1991) threecue condition. It is important to note, however, that the effects of store in general are small.

Country. The estimated effect sizes of the country-oforigin treatment on perceived quality under multiple cue

conditions are larger than the effect sizes of price and store

reported by Dodds et al. (1991). This finding suggests that

country of origin is a potentially important extrinsic quality cue. However, our findings indicate that under multiple

extrinsic-cue conditions, the effect size of country of origin is small when compared with the effect size of price on

perceived value reported by Dodds et al. (1991) and found

in this study.

Product Differences

The results suggest that there may be product-related

variables that moderate the effects of the extrinsic quality

and sacrifice cues. In the wristwatch experiment, the store

treatment significantly affected perceived value both

directly and indirectly via the perceived quality mediator

variable. On the other hand, in the calculator experiment,

the store treatment had no significant direct or indirect

linkages with perceived value. One explanation for these

results is that, when compared to wristwatches, calculators

may be perceived by consumers to be more widely

Teas, Agarwal / Eb'FEL-'TSOF EXTRINSIC CUES

available across retail stores. Consequently, store name

may not be an important factor affecting the perceived

quality of calculators. However, the selection of wristwatches in a particular retail store is usually limited. Consequently, the retail stores through which the wristwatch is

marketed may be a factor that differentiates wristwatches.

The result may be that the retail store affects perceived

value of wristwatches through more complex processes.

Examples of these processes could be the effect of the

retail store on the perceived risk and the degree to which

the product is congruent with self-image.

There may be product differences that explain the brand

effect differences found in the two experiments. In the case

of calculators, brand name may function primarily as a

perceived quality cue. However, in the case of wristwatches, brand name may be a more complex cue. For

example, because of the personal-image implications of a

wristwatch, the image associated with a brand name may

be more likely to enhance the benefits associated with a

wristwatch than the benefits associated with a calculator.

Price differences across wristwatch brands may be

larger than price differences across the types of calculators

examined in this study. This may have caused the respondents to associate different acquisition and transaction values with the wristwatch than they associated with the calculator. Grewal et al. (1998) tested models involving the

effects of price comparisons on consumers' value perceptions and behavioral intentions. In contrast to our conceptualization of value, Grewal et al. (1998) specified perceived value in terms of two separate dimensions-acquisition value and transaction value. Acquisition value

is defined as "the buyers' net gain (or tradeoff) from

acquiring the product or service . . . which takes into

account both price and quality" (Grewal et al. 1998).

Transaction value is defined as "the perception of psychological satisfaction or pleasure obtained from taking

advantage of the financial terms of a price deal" (Grewal

et al. 1998). To the degree to which price differences

across wristwatches (calculators) are large (small),

acquisition value and transaction value may be more (less)

important mediator variables in the evaluation of wristwatches (calculators).

Implications for Future Research

The results support the findings reported by Dodds et

al. (1991) that indicate strong associations between extrinsic quality cues and perceived quality. Although the Dodds

et al. (1991) findings suggested that the role of price as a

quality cue may be diminished as additional cues are

added, our findings indicate that the respondents continued to rely on price as a quality cue in the presence of other

extrinsic cues. In addition, the results extend the Dodds et

al. (1991) findings by providing support for their hypothesized positive linkage between price and perceived

287

sacrifice and by indicating that both perceived quality and

perceived sacrifice mediate the relationships between the

extrinsic cues examined and perceived value.

The concept of perceived sacrifice was operationalized

as a measure of monetary sacrifice. However, according to

Zeithaml (1988), consumers may also incur nonmonetary

sacrifices such as time, effort, and search costs. If consumers assemble durable goods, prepare packaged foods, or

travel large distances to acquire products, they incur additional costs that might influence the assessment of product

value. Future research should incorporate these nonmonetary sacrifices in the model of perceived value by developing a formalized definition of perceived sacrifice and by

empirically testing the model using measures based on the

formalized definition. 5

The fact that the linkages between the extrinsic cues

and perceived value may not be completely mediated by

perceived quality and sacrifice suggests that there may be

additional variables that mediate the linkages. One variable that could be examined in future research is perceived

risk (Shimp and Bearden 1982). Wood and Scbeer (1996),

for example, suggest that consumers' evaluations of a

"deal" may be a function of perceived benefits, costs, and

risk. A possible explanation for the differences in the

results of the two experiments is that, for the students participating in the study, the effects of risk perceptions on

perceived value may be stronger for watches than for

calculators.

Given the nonsignificant findings concerning the

country-of-origin moderator variable effects, a question

for future research involves the degree to which the impact

of country of origin as a moderator of brand, store, and/or

price quality cue effects may be decreasing over time.

With the increasing globalization of business and the tendency of manufacturers to locate production facilities in

different countries to produce branded products, consumers may be increasingly likely to assume that the quality of

an established branded product will be about the same

regardless of production location. 6 On the other hand,

some products may be less likely to be routinely or effectively manufactured in different countries. For example,

the manufacturing of some complex, high-technology

products may be perceived by consumers to involve manufacturing processes that are difficult to manage or that

require a highly educated workforce. Consequently, the

effect of a strong brand name may be diminished if the

product is manufactured in a country characterized by

questionable manufacturing or workforce sophistication.

The possibility that country of origin effects are product specific has been examined by Kaynak and Cavusgil

(1983). In a study conducted in Canada, they found that

consumers ranked countries differently for different products. Japan, for instance, ranks high in electronic products

but low in food products. France, on the other hand, ranks

high on fashion merchandise but lower on other product

288

JOURNALOF THE ACADEMYOF MARKETINGSCIENCE

classes that were examined. Even in today's environment

where technologies and finns freely migrate across borders, consumers sometimes assess higher quality to a

product when they think that the country in which it is

made is capable o f producing a high-quality product

(Agarwal and Sikri 1996; C h a t 1993).

Grewal et al. (1998) specify and test models involving

the effects of price comparisons on consumers' value perceptions and behavioral intentions. In contrast to our conceptualization of value, Grewal et al. (1998) specified perceived value in terms of acquisition value and transaction

value. An issue that should be examined in future research

is the effects of quality and value cues on acquisition value

and transaction value. Grewal et al. (1998) argue that

acquisition value is related to both price and quality. Quality cues, therefore, can be expected to affect acquisition

value via their effect on the perceived quality. Furthermore, Grewal et al. (1998) argue that transaction value

involves satisfaction derived from the price deal and that

transaction value is a predictor of acquisition value. This

causal linkage between transaction value and acquisition

value suggests complex price-perceived value linkages.

First, the results of our study suggest price cues may positively a f f e c t a c q u i s i t i o n value i n d i r e c t l y via the

price---~perceived quality--~acquisition value route. Second, the Grewal et al. (1998) model (Figure 2, p. 49) suggests that the price cue may negatively affect acquisition

value via a negative direct effect on transaction value,

which, in turn, is positively related to acquisition value.

Third, the price cue may positively affect acquisition value

via a positive linkage with internal reference price, which,

in turn, Grewal et al. (1998) argue, has a positive linkage

with transaction value.

Limitations

Important limitations of this study involve the mediation analyses. The findings involving mediation are

exploratory and inconclusive and, therefore, should be

interpreted with caution. First, the model tested in this

study is incomplete and, therefore, underspecified (see

Zeitham11988 for an alternative model specification). The

findings of incomplete mediation, however, are consistent

with the Zeithaml (1988) model. Second, the constructs,

especially the perceived sacrifice construct, are not fully

developed conceptually. Perceived sacrifice is conceptualized to be a unidimensional construct measured via two

items. Research by Zeithaml (1988) indicates that perceived sacrifice may be multidimensional.

These measurement limitations represent a possible

explanation for our findings suggesting incomplete

mediation. Third, the use of summed scales for covariates

that are measured with error can lead to incorrect inferences with respect to the effect of a manipulation (Huitema

1980).

SPRING 2000

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the three anonymous reviewers and

A. Parasuraman, the editor, for their numerous helpful

comments on previous drafts of this article. Both authors

contributed equally to this article.

NOTES

1. One respondent did not complete the questionnaire involving

wristwatches. As a result, the sample size for the wristwatch experiment

was 529.

2. Factor analysis of the wristwatch data indicated that the item

"value for the money,"althoughloadinghigh (.69) on the intended factor,

also loaded somewhathigh on another factor (.42). Thus, the analysis reported in the article was repeated by using a perceived-value summated

scale with this item omitted. This modificationdid not alter the findings

of the study.

3. We specify specifictwo-way interactions in our hypotheses;thus,

we focused our tests on these a priori specified interaction effects. We

note, however,that the experimental design allowedthe estimation of all

possible interaction effects and that the four-wayinteractionwas statistically significant. On the basis of Cohen and Cohen (1983), we do not attempt to interpret this four-wayinteraction--"Interaction IVs, like any

other kind, should only he included if there is serious reason to believe

that they ate real. Otherwise, the value of the conclusions from the research investigation.., is jeopardized" (Cohen and Cohen 1983:348).

4. As recommendedby a reviewer,two additional analysisof covariante (ANCOVA)tests were performed--one entering quality only as a

covariate and one entering sacrifice only as a covariate. The results involvingwristwatches, which are presented in Table2, indicate that, with

the exception of a significantbrand-by-storeinteraction (R < .05), entering only perceived quality as a covariateproduced results similar to the

two-covariatemodel. The results indicate entering only sacrifice as a covariate resulted in the countrymain effect and the brand-by-storeinteraction becoming significant (p < .01). The results involving calculators,

which are presented in Table 3, indicate that, with the exception of a significant price-by-countryinteraction (p < .05), entering only perceived

qualityas a covariateproducedresults similarto the two-covariatemodel.

However,the results indicatethat entering only sacrifice as a covafiateresuited in two additional significant main effects (/7 < .001)--brand (B)

and country(C). In general, these findings suggestthat perceivedquality

is a more important mediator variable than perceived sacrifice.

5. Researchinvolvingthe linkages between exogenouscues, quality,

sacrifice, and value is sufficientlymature to benefit from attempts to formalizethe definitions of the variables (see Teas and Palan 1997for procedures and examples of the theory formalizationprocess).

6. A recent editorial in The EconomistCMercedes Goes to Motown"

1998) supports this proposition in a discussion of the Daimler/Chrysler

merger by suggesting the following: "At a time when cars and components all resemble one another, a national identity has become a vital part

of the brand. Those who buy Mercedes are baying German engineering.., regardless of where the car is built" (p. 15).

REFERENCES

Agarwal, Sanjeev and Samir Sikri. 1996. "Country Image: Consumer

Evaluation of Product CategoryExtensions." InternationalMarketingReview 13 (4): 23-39.

Baker, Julie, Dhruv Grewal, and A. Parasuraman. 1994. "The Influence

of Store Environmenton Quality Inferencesand Store Image."Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 22 (4): 328-339.

Teas, Agarwal / EFFECTS OF EXTRINSIC CUES 289

Bearden, William O. and Terence A. Shimp. 1982. "The Use of Extrinsic

Cues to Facilitate Product Adoption,' Journal of Marketing Research

19 (May): 229-239.

Bilkey, Warren J. and Edk Nes. 1982. "Country-of-Origin Effects on

Product Evaluations,' Journal of International Business Studies 13

(Spring-Summer): 89-99.

Chao, Paul. 1993. "Partitioning Country of Origin Effects: Consumer

Evaluations of a Hybrid Product,' Journal of international Business

Studies 24:291-306.

Cohen, Jacob and Patrieia Cohen. 1983. Applied Multiple Regression~Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2d ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Curry, David J. and Peter C. Riesz. 1988. "Prices and Price/Quality Relationships: A Longitudinal Analysis,' Journal of Marketing 52 (January): 36-51.

Darling, John R. and Danny R. Arnold. 1988. ''Foreign Consumers' Perspective of the Products and Marketing Practices of the United States

Versus SelectexlEuropean Countries,' Journal of Business Research

17 (November): 237-248.

Dawar, Niraj and Philip Parker. 1996. "Marketing Universals: Consumers' Use of Brand Name, Price, Physical Appearance, and Retailer

Reputation as Signals of Product Quality." Journal of Marketing 58

(April): 81-95.

Dodds, William B. and Kent B. Monroe. 1985. "The Effect of Brand and

Price Information on Subjective Product Evaluation,' Advances in

Consumer Research 12:85-90.

- - , and Dhruv Grewal. 1991. "Effects of Price, Brand, and

Store Information on Buyers' Product Evaluation." Journal of Marketing Research 28 (August): 307-319.

Erickson, Gary M. and Johny K. Johansson. 1985. "The Role of Price in

Multi-Attribute Product Evaluations." Journal of Consumer Research 12 (September): 195-199.

--,

and Paul Chao. 1984. "Image Variables in MultiAttribute Product Evaluations: Country-of-Origin Effects." Journal

of Consumer Research 11 (September): 694-699.

Grewal, Dhruv, Kent B. Monroe, and R. Krishnan. 1998. "The Effects of

Price-Comparison Advertising on Buyers' Perceptions of Acquisition Value, Transaction Value, and Behavioral Intentions?' Journal of

Marketing 62 (April): 46-59.

Hair, Joseph E, Rolph E. Anderson, Ronald L. Tatham, and William C.

Black. 1995. Multivariate Data Analysis With Readings. 4th ed.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Han, C. Min. 1989. "Country Image: Halo or Summary Construct" Journal of Marketing Research 26 (May): 222-229.

and Vern Terpstra. 1988. "Country-of-Origin Effects for UniNational and Bi-National Product,' Journal oflnternational Business Studies 19 (Summer): 235-255.

Hanssens, Dominique and Johny K. Johansson. 1991. "Rivalry as Synergy? The Japanese Automobile Companies' Export Expansion."

Journal of lnternational Business Studies 22:503-526.

Hastak, Manoj and Sung-Tal Hong. 1991. "Country-of-Origin Effects on

Product Quality Judgments: An Information Integration Perspective?' Psychology and Marketing 8 (Summer): 129-143.

Hanser, John R. and Glen Urban. 1986. "The Value Priority Hypotheses

for Consumer Budget Plans,' Journal of Consumer Research 12

(March): 446-462.

Huitema, B. E. 1980. The Analysis ofCovariance and Alternatives. New

York: John Wiley.

Johansson, Johny K. 1989. "Determinants and Effects of the Use of

'Made in' Labels,' International Marketing Review 6 (1): 47-58.

, Susan P. Douglas, and Ikujiro Nonaka. 1985. "Assessing the Impact of Country of Origin on Product Evaluations: A New Methodological Perspective." Journal of Marketing Research 22 (November):

388-396.

Kaynak, Erdener and S. Tamer Cavusgil. 1983. "Consumer Attitudes Towards Products of Foreign Origin: Do They Vary Across Product

Classes ?" International Journal of Advertising 2:147-157.

Lichtenstein, Donald R.. Peter H. Block. and William C. Black. 1988.

"Correlates of Price Acceptability." Journal of Consumer Research

15 (September): 243-252.

; Nancy M. Ridgway, and Richard G. Netemeyer. 1993. "Price

Perception and Consumer Shopping Behavior: A Field Study." Journal of Marketing Research 30 (May): 234-245.

MacKenzie, Scott B. and Richard J. Lutz. 1989. "An Empirical Examination of the Structural Antecedents of Attitude Toward the Ad in an

Advertising Pretesting Context." Journal of Marketing 53 (April):

48-65.

"Mercedes Goes to Motown" 1998. The Economist, May 9, p. 15.

Milgrom, Paul and John Roberts. 1986. "Price and Advertising Signals of

Product Quality" JournalofPoliticalEconomy 55 (August): 10-25.

Monrr Kent B. and Joseph D. Chapman. 1987. "Framing Effects on

Buyers' Subjective Product Evaluations."Advances in ConsumerResearch 14:193-197.

~and

R. Krishnan. 1985. "The Effect of Price on Subjective Product Evaluation,' In Perceived Quality: How Consumers Hew Stores

and Merchandise. Eds. Jacob Jacoby and Jerry C. OIson. Lexington,

MA: Lexington Books, 209-232.

Rao, Akshay R. and Kent B. Monroe. 1989. "The Effect of Price, Brand

Name, and Store Name on Buyers' Perceptions of Product Quality:

An Integrative Review." Journal of MarketingResearch 26 (August):

351-357.

Schmidt, Jeffrey B. and Richard A. Spreng. 1996. "A Proposed Model of

External Consumer Information Search?' Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science 24 (3): 246-256.

Shimp, Terence A. and William O. Bearden. 1982. "Warranty and Other

Extrinsic Cue Effects on Consumers' Risk Perception." Journal of

Consumer Research 9 (June): 38-46.

Stokes, Raymond C. 1985. "The Effects of Price, Package Design, and

Brand Familiarity on Perceived Quality." In Perceived Quality: How

Consumers View Stores and Merchandise, Eds. Jacob Jacoby and

Jerry C. Olson. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 233-246.

Teas, R. Kenneth and Kay Palan. 1997. "The Realms of Scientific Meaning Framework for Constructing Theoretically Meaningful Nominal

Definitions of Marketing Concepts." Journal of Marketing 61

(April): 52-67.

Thorelli, Hans B., Jeen-Su Lira, and Jongsuk Ye. 1989. "Relative Importance of Country-of-Origin, Warranty and Retail Store Image on

Product Evaluation." International Marketing Review 6 (1): 35-46.

Tse, David K. and Gerald G. Gore. 1993. "An Experiment on the Salience

of Country-of-Origin in the Era of Global Brands." Journal of International Marketing 1 (1): 225-237.

Wall, Marjorie, John Liefeld, and Louise A. Heslop. 1991. "Impact of

Country-of-Origin Cues and Patriotic Appeals on Consumer Judgments: Covariance Analysis,' Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science 19 (Spring): 105-113.

Wheatley, John J. and John S. Y. Chiu. 1977. "The Effects of Price, Store

Image, and Product and Respondent Characteristics on Perceptions

of Quality,' Journal of Marketing Research 14 (May): 181-186.

Wood, Charles M. and Lisa K. Scheer. 1996. "Incorporating Perceived

Risk Into Models of Consumer Deal Assessment and Purchase Intent." Advances in Consumer Research 23:399-404.

Wright, Peter L. 1975. "Consumer Choice Strategies: Simplifying vs.

Optimizing." Journal of Marketing Research 11 (February): 60-67.

Zeithaml, Valerie A. 1988. "Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and

Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence." Journal of

Marketing 52 (July): 2-22.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

R. Kenneth Teas is a distinguished professor of business in the

Department of Marketing, College of Business, Iowa State University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Oklahoma. His areas of research include consumer behavior and

decision processes, marketing research methods, services marketing, and sales force management. His articles have been published in numerous journals, including the Journal o f Marketing,

the Journal of Marketing Research, the Journal of Consumer Research, the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, the

American Journal of Agricultural Economics, the Journal o f Re-

290

JOURNALOF THE ACADEMYOF MARKETINGSCIENCE

tailing, the Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management,

SPRING 2000

ing Management.

search include multinational marketing strategies, modes of foreign

market entry, and sales force management. His articles have been

published in the Journal of ConsumerResearch, the Journal of

Sanjeev Agarwal is an associate professor in the Department of

Marketing, College of Business, Iowa State University. He received his Ph.D. from The Ohio State University. His areas of re-

International Marketing, International Marketing Review, Industrial Marketing Management, the Journal of International

Business Studies, the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, and the Journalof PersonalSelling and SalesManagement.

the Journal of Occupational Psychology, and Industrial Market-

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Century 21 South Western Accounting Answer Key Free PDF Ebook Download Century 21 South Western Accounting Answer Key Download or Read Online Ebook Century 21 SouthDocument8 paginiCentury 21 South Western Accounting Answer Key Free PDF Ebook Download Century 21 South Western Accounting Answer Key Download or Read Online Ebook Century 21 SouthJohn0% (4)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Service ManualDocument582 paginiService ManualBogdan Popescu100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Transformative SERVICE Research An Agenda For The FutureDocument8 paginiTransformative SERVICE Research An Agenda For The FutureDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- X Blocker Et Al. 2011 Applying A TCR Lens To Understanding and Alleviation Porverty PDFDocument9 paginiX Blocker Et Al. 2011 Applying A TCR Lens To Understanding and Alleviation Porverty PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- BLOCKER - Et Al - 2013 - Understanding Poverty and Promoting Poverty Alleviation Through Transformative Consumer Research PDFDocument8 paginiBLOCKER - Et Al - 2013 - Understanding Poverty and Promoting Poverty Alleviation Through Transformative Consumer Research PDFaugustofhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using The Base-Of-The-Pyramid Perspective To Catalyze PDFDocument6 paginiUsing The Base-Of-The-Pyramid Perspective To Catalyze PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Practice of Transformative Consumer Research PDFDocument7 paginiThe Practice of Transformative Consumer Research PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Costs and Benefits of Consuming PDFDocument7 paginiThe Costs and Benefits of Consuming PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Macromarketing-2014-Viswanathan-8-27 PDFDocument21 paginiJournal of Macromarketing-2014-Viswanathan-8-27 PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aula 2 The Four Service Marketing Myths PDFDocument12 paginiAula 2 The Four Service Marketing Myths PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Macromarketing-2014-Saatcioglu-122-32 PDFDocument12 paginiJournal of Macromarketing-2014-Saatcioglu-122-32 PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mick Origins Qualities and Envisionments of TCR-libre PDFDocument54 paginiMick Origins Qualities and Envisionments of TCR-libre PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incorporating Transformative Consumer Research Into The Consumer Behavior Course Experience PDFDocument9 paginiIncorporating Transformative Consumer Research Into The Consumer Behavior Course Experience PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transformative Consumer ResearchDocument4 paginiTransformative Consumer ResearchDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Small Scale Farming and Agricultural Products Marketing For Sustainable Poverty Alleviation in NigeriaDocument8 paginiSmall Scale Farming and Agricultural Products Marketing For Sustainable Poverty Alleviation in NigeriaDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Uses of Marketing TheoryDocument20 paginiThe Uses of Marketing TheoryDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer SymbolismDocument14 paginiConsumer SymbolismDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture Fashion BlogDocument24 paginiCulture Fashion BlogDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aula 12 Understanding Retail Experiences PDFDocument29 paginiAula 12 Understanding Retail Experiences PDFDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer Fantasies HollbrookDocument9 paginiConsumer Fantasies HollbrookDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Youth CultureDocument18 paginiYouth CultureDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- National CulturesDocument29 paginiNational CulturesDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Positivism and InterpretativismDocument15 paginiPositivism and InterpretativismDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender MasculinityDocument20 paginiGender MasculinityDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social ClassDocument14 paginiSocial ClassDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture StarbucksDocument13 paginiCulture StarbucksDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- SelfconceptDocument15 paginiSelfconceptDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group e TribaliztionDocument13 paginiGroup e TribaliztionDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aula 4 Historical MethodDocument17 paginiAula 4 Historical MethodDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature of AttitudesDocument33 paginiNature of AttitudesDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Consumer Research, Inc.: The University of Chicago PressDocument17 paginiJournal of Consumer Research, Inc.: The University of Chicago PressDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Consumer Research, IncDocument9 paginiJournal of Consumer Research, IncDante EdwardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ground Vehicle Operations ICAODocument31 paginiGround Vehicle Operations ICAOMohran HakimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fuses f150Document7 paginiFuses f150ORLANDOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3: Literature Review and CitationDocument3 paginiModule 3: Literature Review and CitationLysss EpssssÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exposition Text Exercise ZenowskyDocument8 paginiExposition Text Exercise ZenowskyZenowsky Wira Efrata SianturiÎncă nu există evaluări

- IES 2001 - I ScanDocument20 paginiIES 2001 - I ScanK.v.SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- PC-ABS Bayblend FR3010Document4 paginiPC-ABS Bayblend FR3010countzeroaslÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labour Law Assignment - Gross NegligenceDocument6 paginiLabour Law Assignment - Gross NegligenceOlaotse MoletsaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Algebra1 Review PuzzleDocument3 paginiAlgebra1 Review PuzzleNicholas Yates100% (1)

- Nokia 2690 RM-635 Service ManualDocument18 paginiNokia 2690 RM-635 Service ManualEdgar Jose Aranguibel MorilloÎncă nu există evaluări