Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

GEAI Position Paper On Wind Energy

Încărcat de

Good Energies Alliance IrelandTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

GEAI Position Paper On Wind Energy

Încărcat de

Good Energies Alliance IrelandDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Table of Contents

Abstract................................................................................................................................................................... 3

1.

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 5

2.

Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 6

3. Thesis ................................................................................................................................................................. 7

4.

5.

6.

7.

Arguments against Wind Energy .................................................................................................................... 7

4.1

Project Planning Process and Consultation ............................................................................................... 8

4.2.

Intermittency ............................................................................................................................................. 9

4.3.

Environmental impacts/concerns .............................................................................................................. 9

a)

Noise pollution........................................................................................................................................... 9

b)

Visual aspect .............................................................................................................................................. 9

c)

Wildlife....................................................................................................................................................... 9

d)

Tourism ..................................................................................................................................................... 9

Counter-arguments....................................................................................................................................... 10

5.1

Project Planning Process and Consultation ............................................................................................. 10

5.2.

Intermittency ........................................................................................................................................... 11

5.3.

Environmental impacts ............................................................................................................................ 11

a)

Noise and visual impact ........................................................................................................................... 12

b)

Wildlife ..................................................................................................................................................... 12

c)

Tourism .................................................................................................................................................... 12

Case studies .................................................................................................................................................. 13

6.1

Isle of Gigha, Scotland.............................................................................................................................. 13

6.2

Languedoc-Roussillon Region, France (1) ................................................................................................ 13

6.3

Languedoc-Roussillon Region, France (2) ................................................................................................ 13

6.4

Rheinland-Pfalz Region, Germany ........................................................................................................... 13

Sustainable Development Pillars underpin the Thesis ................................................................................. 14

7.1.

Social implications of Wind Energy Development ................................................................................... 14

7.2.

Economic gains ........................................................................................................................................ 15

7.3.

Environmental gains ................................................................................................................................ 16

8.

Our position on Wind Energy........................................................................................................................ 17

9.

References .................................................................................................................................................... 18

Page | 1

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Abstract

Wind power is considered to be a clean source of energy with an important role in the global development of

renewable energy. The objective of this paper is to present both the pros and the cons of wind energy in Ireland,

with a focus on the most important issues: the planning process and consultation, intermittency and

environmental impacts.

Throughout the paper, a clear difference will be made between three types of projects: community-led,

developer-led and developer-led with shares owned by the community. Each of these approaches to wind

energy development has social, economic or environmental gains and obstacles. Adopting a collaborative

approach to planning and involving different players in the process is one of the practices that has positive

outcomes. Regarding environmental impacts, the analysis proves these to be generally subjective and good

practice in reducing opposition to wind farms is the involvement of local communities in choosing the location

and resulting in real benefits to them.

These conclusions are supported by four case studies from Scotland, France and Germany. In each of these, a

new approach to the problem is presented which could be used for future wind energy development in Ireland.

Finally, the paper will present the position of Good Energies Alliance Ireland regarding wind development in

Ireland with arguments supported by the three pillars of sustainable development: social implications, economic

gains and environmental impacts.

Page | 3

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

1. Introduction

20th century, fossil

fuels become the

main source of

energy

Causing global

warming and

changes in the

climate system

Vital to keep

global warming

to 20C

Before the industrial revolution energy demand per person was modest. People relied on the

sun and wood for heating and on wind for sailing ships and pumping water. With the invention

of the steam engine, there was a shift in resources used and coal became the main source of

th

energy. In the 20 century, people started using oil and petroleum, reducing the cost of energy

and improving the quality of transportation, industry, residential heating and so on [1]. Globally,

fossil fuels, such as coal, oil and gas, are still being used as a primary source of energy. In

Ireland, it has been calculated that 98% of everything we use has been made or grown with the

aid of fossil fuels.

However, along with facing depletion, fossil fuels are a source of concern regarding their effects

on the environment through CO2 emissions, causing global warming and extreme weather

(climate change) [2]. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (UNIPCC)

from November 2014 states that continued emission of greenhouse gases will cause further

warming and changes in the climate system.

Such impacts of climate change can be:

Ecological impacts (sea level rising, glaciers melting, artic sea ice cover continuing to

shrink, biodiversity loss etc.),

Financial impacts (increased poverty, coastal flooding, etc.) or

Social impacts (food and water shortages, increased displacement of people and so on).

Before the invention of the steam engine, the atmosphere contained about 280 molecules of

CO2 for every one million molecules in the air (280 ppm). Atmospheric CO2 concentration in

1958, as measured by Dr. Charles Keeling on top of Mauna Loa in Hawaii, was 320 ppm. With the

increasing use of coal, oil and gas, today CO2 concentration has reached 400 ppm [3]. If we

continue to burn fossil fuels and release CO2 in the atmosphere, on a business as usual

trajectory, the temperature by the end of the century could increase by as much as 4 to 7

o

degrees centigrade ( C), which would have devastating effects on the planet [4]. It is vital to

o

keep global warming to 2 C and an immediate international response to climate change is

required to achieve this.

Figure 1

Three Pillars of

CO2 reduction

Figure 1: Three Pillars of Co2 reduction

Source: Authors own

Page | 5

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Ireland needs to

develop a bold

approach

In trying to achieve the carbon targets set through the Kyoto Protocol , many countries are

developing strategies that focus on reducing carbon emissions through the use of renewable and

clean energy sources, such as wind and solar. To reduce the effects of climate change, the EU has

ambitious objectives as part of its strategy for Climate and Energy, such as 40% reduction in

carbon emission by 2030 and 80% by 2050. To achieve these targets Ireland needs to develop a

bold approach. The focus must be on three main areas: energy savings on the demand side,

efficiency improvements in the energy production, and replacement of fossil fuels by various

sources of renewable energy [5] (Figure 1).

Developing the

position of GEAI

on wind energy

The aim of this paper is to present an objective overview of wind energy industry in Ireland,

looking at objections to further development of the industry, presenting counter arguments and

developing a theme which will form the position of Good Energies Alliance Ireland (GEAI) on

wind energy in Ireland.

2. Background

90% of Irelands

fossil fuels are

imported

Today, energy is essential in shaping the human condition, with fossil fuels supplying about 81%

of the global economy [6]. In Ireland, 84.7% of our energy comes from fossil fuels, 90% of which

is imported. But this dependence cannot continue without putting the economy and the

environment at risk. Major threats that we are facing today are energy insecurity and the rising

prices of conventional energy sources, with significant effects on the economy and political

stability [7].

Figure 2: Energy imports, net (% of energy use)

Source: Word Bank

Roadmap for

Ireland critical to

achieve 80%

reduction of CO2

by 2050

Are these threats something that can be addressed? Yes, they are. Recently, many countries

have developed different pathways to achieve a carbon neutral status. One example is The

Solution Project in the United States, where the authors present a roadmap for each individual

state to convert all-purpose (electricity, transportation, heating/cooling, and industry) energy

infrastructures to ones powered by wind, water, and sunlight (WWS) by 2050 [8]. The

development of such a roadmap for Ireland is critical in achieving the EU target of at least 80%

carbon emissions reduction by 2050. Taking into account our well-developed agriculture sector,

along with the renewable resources available, Irelands strategy could be focused on several

solutions, among them being solar photovoltaics (PVs); biofuel from animal residue and

sustainable crops, wind power, developed onshore as well as offshore, and wind powered

pumped hydro storage systems.

Kyoto Protocol is an international treaty produced by the the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate

Change (UNFCCC) that sets targets of greenhouse gasses emissions for industrialized countries, having 1990 as

a base year. http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php

Page | 6

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

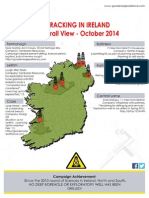

The first Irish commercial wind farm was commissioned at Bellacorrick, Co Mayo in 1992,

comprised of 21 wind turbines with a total installed capacity of 6.45 Megawatts (MW). By

November 2014, the island of Ireland had an installed wind capacity of 2816 MW from a total of

216 wind farms. From this, 182 are located in the Republic of Ireland representing 2190 MW

installed capacity. In 2013, according to the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI), wind

power supplied 16.4% of total electricity consumption.

Small wind

projects in Ireland

resulted in little

resistance

Now, many antiwind groups and

networks have

sprung up

Up to recently, wind projects in Ireland were small scale, creating little or no public resistance. In

fact, many of them resulted in a feel-good factor among local communities and one of the

electricity supply companies (Airtricity) marketed its electricity as mainly coming from clean

(wind) energy [9]. However, in 2013, the Midland Energy Export Project was announced, which

proposed a major project exporting wind energy to Britain. This plan included the construction

of over 2,000 turbines across five counties with associated electricity power lines. Media reports

suggested that the turbines could each have up to 5 MW capacity and be 183m high. This

resulted in an outcry from local communities, raised peoples awareness about wind energy

impacts and created controversy about the planning and decision-making process for the entire

industry.

Following the Midland Energy project proposal, many anti-wind groups and networks have

sprung up (e.g. Wind Aware Ireland). Most of these are in the Midlands, in communities that

would be most impacted by the project; others are in different parts of the country. Even small

proposals for wind farms now can be opposed by local communities and it is recognised by the

Department of Energy that difficulties lie ahead for larger projects, given the current opposition

[10].

3. Thesis

The thesis propounded by this paper is:

The development

of wind energy is

an essential part of

decarbonisation of

energy production

in Ireland

The development of wind energy is an essential part of the decarbonisation of

energy production in Ireland but such development must have genuine benefits for

and buy-in from the Irish people.

In this paper, we will

look at the arguments against wind energy development in Ireland,

counter those arguments and

develop our thesis.

4. Arguments against Wind Energy

Project Planning,

Intermittency

and

Environmental/

health issues

Important arguments can be summarised as

1. Project planning process and consultation issues associated with wind energy

developments

2. Intermittency

3. Environmental/health issues and concerns

Other concerns include economics and jobs claims which have been noted but will not be

discussed at length in this paper. One point to make is that, in the absence of a significant oil or

gas industry in Ireland, jobs in the wind energy industry do not substitute for jobs elsewhere.

Page | 7

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

4.1

Developer-led plans

lead to opposition

Few benefits for

local communities

Public

participation

inadequate

Turbines sited in

unsuitable

locations

Project Planning Process and Consultation

In Ireland, until now, the government has not encouraged community led projects and has

been focused more on developer-led plans; from the perspective of the authorities this may be

seen as an easier approach, as they have to deal only with the developers. But this approach is

the biggest reason why wind projects now face such opposition. Developments led by electricity

companies with no other stakeholders taking part in the planning process can lead to many

issues being overlooked. In Ireland, out of 182 operational wind farms, only one is community

owned. In other countries, such ownership is common (see Case Studies).

In addition, none of the developer-led projects bring significant economic benefits to the local

communities nearby, e.g. reduction in energy bills, opportunity to invest in the wind farm. With

the existing technology for wind energy, increased efficiencies, and the high potential for Ireland

to develop the industry, an important aspect when proposing a developer led wind project

should be community payback. This would not only lead to improved quality of life in the

community but also would help with the acceptance of the project. The drop in wholesale

electricity price in December 2013 and January 2014 that resulted from the strong wind

recorded in that period benefited only the electricity companies, with citizens having no benefits

from this increased efficiency and lower costs. This supports the concept of local community

ownership of power.

Public participation in decisions regarding wind energy project proposals can also be

b

considered inadequate. Under the Aarhus Convention , the state is obliged to make

environmental information available and to involve the public (individuals and their associations)

in environmental decision making. A public consultation process must be engaged in before a

final decision is agreed upon. In Ireland, the Aarhus Convention was only ratified in June 2012;

before then, smaller projects in essence bypassed a public consultation phase. (Requirements

for public notices of planning applications were minimal and these notices often escaped the

notice of the public.)

Another problem derived from lack of consultation in the development of wind farms is around

turbine location. For example, construction too close to houses, situation in a protected area,

interfering with wildlife and visual impact on the landscape are just some of the issues regarding

the siting of the wind farms. These are referred by planners and decision makers as

communication problems, an expression that could be seen to denigrate genuine concerns felt

by the public. However, research done on public perception or on the planning process regarding

wind power schemes suggest that, in fact, poor communications may indeed play a role in the

success of the projects [11].

Irelands main anti-wind campaign was developed after the proposal for the Energy Export

Project in the Midlands was made public. The scale of the project and the fact that the

communities were not involved in planning the project were two major points of concern for

everybody. Social acceptance of different energy projects represents an issue in many countries.

However, several solutions that involve the communities have already been developed [12].

Midlands Energy

Project:

developing a wind

market rather than

improving

quality of life

Some objectives for developing renewable energy projects can be perceived as having a

detrimental outcome. For example, in Ireland, the Midlands Energy Project was proposed with

the aim of exporting clean energy to the United Kingdom. This was not regarded with favour by

many communities. Furthermore, the authorities were seen to be focusing more on developing

the wind industry as a method of reducing carbon emissions, whereas many would prefer an

emphasis on increasing energy efficiency, e.g. through retro-fitting the existing housing stock.

The perception of the Government focussing on developing a wind market instead of trying to

improve quality of life has alienated many citizens, especially in the local areas proposed for

such development.

Aarhus Convention - http://ec.europa.eu/environment/aarhus/

Page | 8

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

4.2.

Intermittency

Wind is intermittent (sometimes blows, sometimes does not) and requires a permanent backup

called Spinning Reserve. When the wind is blowing, gas and coal plants (at 50% efficiency)

continue to run in the background, in reserve, ready to come in on short notice when the wind

dies. Wind energy must be permanently supported by reliable power sources, usually gas

turbines. When the costs of these are included, electricity produced by wind becomes expensive

affecting national competitiveness and fuel poverty (Wind Aware Ireland).

4.3.

Environmental impacts/concerns

The main concern that people have regarding wind projects is their impact on the environment.

Noise perception Although some consider wind power to be environmentally benign, issues like noise pollution,

differs from person the visual aspect and the impacts on wildlife, particularly bird endangerment, are being raised by

to person some experts [2; 13].

a)

Wind turbines can

be considered

visually pleasing

or intrusive

b)

Fears that landscape

may be

compromised

Noise pollution

Noise perception tends to differ from individual to individual, depending of the persons hearing

acuity and the level of acceptance towards the wind project. Opposition to the development

often increases the perception of the noise produced by the turbines. This can create major

annoyance in peoples lives and can lead to stress symptoms such as headaches, feeling tense

and irritable [2; 14]. Furthermore, some research studies claim that low-frequency aerodynamic

noise of wind turbines can bother people by causing sleep disturbances and hearing loss, and can

also hurt the vestibular system [2].

Visual aspect

The visual aspect has proven to be a crucial factor for wind development, but it is difficult to

assess because of the subjective and unquantifiable nature of landscape evaluation [15].

Whilst, for some, wind turbines appear visually pleasing, even beautiful, others find them

intrusive. Even so, many people oppose the development of wind turbines because of the

proximity to their homes [16]. This is also one of the reasons for opposition in Ireland. In

addition to this, the turbines are seen as destroying Irelands world-renowned scenery.

Opponents have also discussed the impacts that the turbines have on the landscape during the

construction phase, such as tracks or the upgrading of the electricity grid. In rural areas, it is

referred to as transforming natural landscapes into landscapes of power [15]. Furthermore, site

preparation activities, machineries, transportation of turbine elements, and siting of

transmission lines can lead to loss of vegetation, birds habitats and wildlife (small animals), soil

erosion and even changes in hydrologic features [16].

c)

wildlife impacted

d)

and tourism affected

Wildlife

The construction of wind projects also impacts on wildlife. It has been demonstrated that wind

facilities kill birds and bats and can lead to disruption in the migration patterns. In addition the

construction of wind farms creates loss in vegetation and loss of habitat for some species of

small animals [16]. The main causes for negative impacts are the location of the turbines, wind

farm in the proximity of habitat resources (such as nesting sites, prey, water, and other

resources), turbine height and design, rotor velocity and so on.

Tourism

Both the perceived visual aspect and the impacts of wind development during construction

created fear among the local communities that the landscape will be compromised. This is an

important aspect because in Ireland tourism plays a major role in the economy and people are

attracted by the pristine landscapes that are found all over the country. Thus, with the

development of wind energy and the erection of wind farms, both in the midlands and in the

coastal areas, there are fears that tourism could be affected.

Page | 9

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

5. Counter-arguments

5.1

Project Planning Process and Consultation

The Irish planning process has always caused controversy, no matter what the issue: housing,

commercial buildings, transport infrastructure, energy infrastructure and so on and recently

deficiencies in the process has caused resistance to energy development projects, especially

wind. It is true that consultation with involved communities has not been done properly in the

past and this has created many problems, but deficiencies in the planning process are not an

argument against wind energy in general.

Communicative

approach

minimises

opposition to

complex projects

Internationally, several practices have been developed to overcome problems with planning

processes. In the 1990s, the communicative approach was introduced involving different

stakeholders in the planning process, such as local authorities, local or national agencies and

other types of organisations, as a new way of approaching the planning of a complex project

tackling a multitude of issues. This wider consultation in the planning process minimises the

chances of opposition in the implementation phase of such projects. Gaining public acceptance

and agreement on the sitting of the turbines is often resolved through collaboration during the

planning process, bottom-up projects can deliver a range of benefits which do not materialise

from topdown, corporate developments [15]. Adopting a communicative approach to planning

has proven to be very effective in many countries. In the Netherlands, research on public

attitudes has proven the ineffectiveness of hierarchical planning compared to collaborative

approaches [11].

Figure 3: Collaborative Planning

Source: Authors own

Another method proving to be effective and used in countries like Germany and Denmark is the

development of community led projects. In general, those opposing wind energy projects do

not explain to the general public the differences between community-led and developer-led

projects. Is this because giving this information could lead to people deciding that wind energy is

actually a good solution for reducing climate change and providing real benefits to local

communities, something that could work against the anti-wind movement?

Community-led

projects

However, it must also be pointed out that developer led projects can have multiple benefits

and, especially in the case of offshore wind, are the most viable option. These projects usually

have a higher generating capacity, which means faster access to the grid and bigger financial

gains. Furthermore, the development of offshore wind farms has proven to be effective in

countries like Denmark, Sweden and United Kingdom and with many projects being proposed for

the future.

Page | 10

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Developer-led

projects can be

accepted

For developer-led projects factors of success are how well-informed local residents are about

wind energy, what the chosen site was previously used for, quality of communication with the

public and public participation in the planning process [17]. In Germany, Denmark, UK and other

European countries the involvement of the community in the development process has led to

general acceptance and a faster implementation of the project [15; 18].

In addition, allowing the community to own one or more turbines within a wind farm (and get

the revenue generated by it) has proven to be more locally acceptable and have fewer problems

obtaining planning permission than others [19]. People will be more inclined to accept wind

farms if they know that this will bring economic gains to them.

Although the development of individual or community owned wind farms did not have priority

Communities must for the government in the past, their position is changing and nowadays national agencies and

get real benefits even energy companies are promoting this approach (Bord na Mona, 2014 anecdotal

evidence). In addition, the government is tackling the connection to the grid problem and

policies are in place to make this more accessible. The creation of Group Processing Approach in

October 2004 had the objective to help communities and speed up the connection of renewable

energy plants by providing standardised procedural steps, and to increase connection security.

Project

Management

is an important

factor

Project Management is an important factor for energy projects. Issues regarding local

integration of the developers, information given to and participation of the public, a network of

support, the ownership of the park and financial support are crucial to the final result [17].

People are more inclined to trust developers that come from their area or, in the case of a small

country like Ireland, if they are local. Who supports the development of the project is also

important. If there are people in the community or local representatives that advocate for the

realisation of the energy project and are involved in promoting it, the chances of acceptance are

higher. Experience has shown that key committed individuals or entrepreneurs can be essential

to success, as are supportive local institutions of various forms [19]. Furthermore, the financial

gains that the development brings either to the community as a whole or the each individual are

often seen as major points of interest.

5.2.

The more wind

power, the more

constant the

electricity output

Intermittency

A study from the American Wind Energy Association (2015) [20] discusses the topic of

intermittency from the perspective of grid operators (in Ireland this is Eirgrid) and states that

contrary to most peoples assumption that winds are highly variable and electricity

demand/supply is fairly stable, the opposite is actually true demand is variable and can change

very rapidly, e.g. at the interval during the Eurovision! The reality is that the more wind power is

added to the grid, the more constant the electricity output as increases in output at one wind

plant tend to cancel out decreases in output at others.

"Moreover, weather forecasting makes changes in wind energy output predictable, unlike the

abrupt outages at conventional power plants" [20]. With regards to the costs needed for the

backup power sources, data collected and presented in the study shows that "the operating

reserve costs for conventional power plants are far larger than the operating reserve costs for

wind generation."

5.3.

General

acceptance of

wind power

Environmental impacts

Surveys have discovered that, compared to other energy sources, there is a general acceptance

of wind power. It seems, therefore, quite puzzling why it is so hard to succeed in building new

wind turbines when people are so much in favour of wind energy [13]. The reason why this

happens is because peoples attitudes regarding wind power vary significantly in the different

stages of development. They suggest a U-shaped curve with attitudes ranging from very

positive (that is when people are not confronted by a wind power scheme in their

neighborhood), to much more critical (when a project is announced), to positive again (some

reasonable time after the construction) [11]. So why does this happen? For many people, the

Page | 11

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

idea of a wind farm being in the proximity of their house, thinking it will destroy the landscape

and impose health risks, becomes a reason for opposing the development.

Figure 4: U-Shaped Curve of attitudes

Source: Authors own based on Wolsink (2007) [11]

a)

Noise and visual

impact are

subjective

b)

Fossil fuel

developments

or deforestation

and urbanisation

have much greater

impact on wildlife

Noise and visual impact

Both the noise and the visual impact caused by wind energy projects are subjective and differ

from individual to individual; different people have different values as well as different levels of

sensitivity [16]. Studies done in Sweden and the Netherlands have found that the perception of

noise is linked with peoples visual perception of the turbines and the belief that they are

intrusive. It is also linked with the lack of economic benefits [21; 22].

Wildlife

The impacts of business as usual on the environment are much more devastating than the

impacts of the wind farms on the landscape. Coal mining, gas extraction through fracking, oil

spills and technologies using refineries are far more harmful to the environment than the

development of wind energy or any other kind of renewable energy source. Fossil fuels use leads

to extensive air, water and ground pollution and, besides harming animals, leads to loss of

vegetation and displacement of habitats. They are also a leading cause of health problems in

humans [7].

In addition, even if turbines do lead to some loss of habitat and birds deaths, these are

negligible compared to other human developments such as deforestation and urbanization [2]. A

study done in the United States has discovered that Buildings, power lines and cats are

estimated to comprise approximately 82 percent of the mortality, vehicles 8 percent, pesticides 7

percent, communication towers 0.5 percent, and wind turbines 0.003 percent, with an estimated

1 billion birds killed globally every year [23].

c)

Tourism

The impact of wind farms on tourism also depends on the perception of the individual. Tourists

supporting wind energy will not be influenced in their decision of vising a place by the

development of a wind farm. An example is the Isle of Gigha where a survey was done on

tourists and nine out of ten people said that the presence of wind farms would have no bearing

on the likelihood of their making a return visit [15].

Wind farms need

not negatively

impact on tourism

Furthermore, with right promotion wind farms can be transformed into attractions. The

Australian Wind Energy Association reports that hundreds of thousands of people visit the wind

farms, either as casual observers stopping in the vicinity of the turbines or by paying to

participate in organized tours. In a number of cases, tourists are able to walk right up to the

base of the tower, gaining a full appreciation of their size and the power generated by these

machines [24].

Page | 12

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

6. Case studies

This chapter will give a short presentation of four study cases from Scotland, France and

Germany. These are examples of wind projects that had favourable results and that present

relevant solutions for the future development of wind energy projects in Ireland.

6.1

Turbines are seen

as symbols of

prosperity

This is a community owned project on the Isle of Gigha in Scotland. It consists of three wind

turbines with a total capacity of 0.7MW. This project is a good example of how the community

ownership increased the acceptance of the turbines, now even being considered as part of the

community, perhaps most tellingly of all, the positive psychological effect of community

ownership is revealed in the fact that the Gigha islanders have given their turbines an

affectionate nickname: the Three Dancing Ladies. [15] In addition, the turbines are seen as

symbols of prosperity, enhancing the islands green image, with no negative effects on the

tourism.

6.2

Link between the

wind project and

the wine-growers

Languedoc-Roussillon Region, France (1)

The second example is a 9-turbine, developer-led project in the Languedoc-Roussillon Region in

France, a project that was first approved in 1999, but not until 2001 did most of the people and

various actors from the community heard about it. Proposed in an area known for its vineyards

and with a well-developed tourism, the main concern of the local people was that the project

will give an industrial look to the landscape. Facing opposition from the winegrowers, the

developers thought of a unique approach and decided to join a nearby wine-cellar cooperative

to create a link between the project and the winegrowers; e.g. combine a visit to the wine caves

with a visit to the wind park [17]. It was in 2004 when the wind farm was realized.

6.3

Turbines located in

more isolated site

Isle of Gigha, Scotland

Languedoc-Roussillon Region, France (2)

This example, a 4-turbine wind park also in the Languedoc-Roussillon Region in France, shows

how the developers learned for previous experience. To gain public acceptance and not face

opposition for the project they choose a more isolated site. This way the turbines will not

interfere with the landscape and together with the economic situation that the commune was in

led to a fast approval.

In the examples from France, the first project shows an example of the failure to integrate the

public into the planning process and the second one shows how the developers learned from

previous experiences and acted accordingly. The isolation of the site and its invisibility to the

nearby community along with the economic situation of the community were major points for

gaining acceptance [17].

6.4

Community-led

project led to

economic gains

for all

Rheinland-Pfalz Region, Germany

A fourth example is a 14 turbine wind park in Rheinland-Pfalz Region in Germany. What is

interesting about this project is that the commune itself initiated the project. The local

authorities decided to transform an old abandoned military zone into an energy park. After

decided to approve the project, a public information meeting was held for the residents, and

with the help of the German Federal Armed Forces who put weather balloons over the site, an

image of how the wind park will look was given to the people. This led not just to a fast approval

but also to economic gains for the community itself and for private investors, some shares of

2500 were jointly owned by several persons [17].

Page | 13

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Practices that can

be used by

communities or

developers

leading to

positive impact

These examples present several practices that can be used either by communities or developers

in the development of future wind farms:

1. The community taking the lead and deciding to develop a renewable energy project in

the area.

2. Involving the community from the beginning in the planning process.

3. Making it possible for the local people to buy shares and so having direct benefits from

the wind park.

4. Choosing an area to site the turbines so that they will have little to no impact on the

landscape

5. Using an old, abandoned area for the location of the project

Other examples of practices that that have proven to have a positive impact are:

1. Creating development plans for an area or county, with regulation as to where wind

farms can be positioned.

2. When the initiative for an energy park comes from the community, the local players can

propose sites from which the developers can choose, so that it fits their needs as well

[17].

3. The developers research and propose several areas suitable for development, but the

final decision regarding the location of the wind park will be made through consultation

with the local authorities and the residents

4. Ensuring that the communities experiences real benefits from the development, either

by part-ownership or reduced bills.

7. Sustainable Development Pillars underpin the Thesis

The propounded thesis is based on the three pillars of sustainable development:

1. Social implications,

2. Economic gains and

3. Environmental protection.

7.1.

Social implications of Wind Energy Development

The impact on the community from the development of wind farms is closely related to how the

project is developed. Community or developer-led projects with a strong involvement from the

local community have been categorized by many critics as good practices [15].

When wind energy project is proposed, either community owned or developer-led, the main

Impact closely factor needed is agreement between all stakeholders. This requires effective public consultation

related to how the and participation as well as a coming together and working as a team for the implementation

project is developed phase. In addition to involvement, community projects must be fair to all the residents, It has

often been argued that local ownership not only produces more active patterns of local support

and higher levels of planning acceptance but is also more equitable [15].

Agreement

between all

stakeholders

vital

In the case of Isle of Gigha, the ownership by the community of the three wind turbines built led

not just to greater acceptance, but also to an increase in community pride. The turbines were

described by the residents as a sign of the islands success and our image as a progressive

community with a sustainable future [15]. Furthermore, the financial side of the project, with

equitable sharing of costs and benefits, led to a more prosperous community, due to the income

generated on a regular basis.

In the case of a developer-led project, especially land based, either new or where more turbines

Community are being built, if the community has a share in the project, benefits can include the lowering of

ownership leads to energy bills for residents living near the turbines and jobs created, as well as income generated.

community pride All of these can have a big impact on the quality of life for the people in the community.

Page | 14

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Gets people

involved in

community life

Another advantage of having a project where the community has a real stake in the project is

that it develops a bond between the residents and gets people more involved in community

life. This, combined with the experience of developing a project, can lead to different plans for

the community that in the longer term have goals to improve quality of life. Furthermore, the

research phase of projects in general includes a more in-depth look at how the community

functions. This can include energy requirements, local jobs or the potential for the community to

provide basic needs, e.g. water, for all the people. Getting to know these issues and what can be

done to improve them can lead to a higher involvement of the residents.

7.2.

Economic gains

The development of wind energy can bring economic gains to the state and to communities.

In 2012, Irelands import bill was estimated at 6.5 billion and the use of the fossil fuels was

Wind energy responsible for 58 million tons of CO2 emissions [25]. For the 2010 2014 period, wind

substitutes for generation meant 1 billion less spend on energy imports, a 12 million tones reduction in CO2

fossil fuels emissions and no extra costs to consumers bills [26]. Besides decreasing the dependence on

energy import, on the national scale, the development of wind energy, or any kind of clean

energy will make Ireland less susceptible to the prices of oil, coal or gas. The increase in fossil

fuels prices come from a rising in global energy demand and the diminishing fossil resources

which, in the future, will impose additional costs on households and enterprises [12].

Figure 5: Co2 Emissions by Source 1990 - 2012

Source: SEAI Energy in Ireland 1990 2012 (2013 Report)[24]

Good for smaller

areas and

communities

Wind energy

projects can give

revenue to local

communities

At the same time, development of wind energy can positively impact smaller areas and

communities. In the case of community owned wind farms and developer-led with shares

offered to the community, both the local authorities and the residents from the area will feel the

benefits. These can be direct gains through the renting of the land, shares owned or jobs created

by the development or indirect benefits from taxes, and energy prices, which do not depend on

the variability of fossil fuels costs. There also can be an increase in tourism if schemes to

integrate the wind parks in tourism strategies are put in place.

The revenues that a wind park can bring may be:

When the location of the park is on public land, the community can benefit from tax

and from rent [17].

When the location is on private land the benefits can go directly to the landowners.

When the project is community-led or developer-led with shares for the residents,

there can be direct economic benefits for the people in the community.

Where wind parks are integrated in tourism strategies, impacts on tourism can be

positive with increased revenues in this sector.

Page | 15

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

Wind energy will

create more jobs

In addition, the development of wind energy will create more jobs for Irish people. Some would

argue that switching from fossil fuels to renewables means that jobs in the coal, oil and gas

industries will disappear so that the development of clean energy does not mean extra jobs but

just displacement of the existing ones. While it might be the case in some countries, in Ireland

the situation is different, mostly because 90% of fossil fuels are imported and the industry is

small, suggesting that wind development will create jobs without displacing existing ones.

7.3.

Environmental gains

Besides social and economic gains, the development of wind is beneficial to the environment.

Along with solar power, hydro-energy, wave, tidal, geothermal, biomass and nuclear, wind

power is a low carbon energy supplier. Actions are being taken in an effort to keep global

0

warming under 2 C and plans involving these low carbon energies have already been developed.

Wind energy will

reduce carbon

emissions in Ireland,

combat global

warming

and reduce air

pollution

Wind turbines less

intrusive than

fossil fuel power

plants

Increase in

agricultural output

means that we

need deep

decarbonisation of

all other sectors

In Ireland, in 2012, 85% of the energy used came from fossil fuels oil, gas and coal, and out of

this 90% was imported from countries like the United Kingdom, Norway, Australia and so on

[24]. Since fossil fuels are the main emitters of CO2, being responsible for the 58 million tons of

CO2 emissions, the development of wind will not only reduce Ireland dependence on import but

will also help reach the CO2 emissions targets for 2030 and 2050. These targets are important in

the context of climate change. Continued increase in greenhouse gases use will accelerate global

warming, which will have devastating impacts on humans: more frequent floods caused by

melting glaciers and rising sea levels; displacement of people and water insecurity. Furthermore,

in some areas droughts will increase leading to declining crop yields. In Africa, for example, this

means leaving millions of people without the ability to produce food.

The development of wind power not only helps in combating global warming, it also reduces

air pollution, which is the sixth leading cause of death, causing over 2.4 million deaths

worldwide [7]. Thus, a main impact that wind energy development has on the people is

reducing the health impacts caused by air pollution from fossil fuels.

Besides air pollution from CO2 emissions, fossil fuels can also pollute the ground and the water.

Coal mining, oil and gas extraction and oil spills have great impacts on the environment, the

wildlife and the people. Wind energy, although it can pose some impacts on people and the

environment, is definitely safer than fossil fuels.

The landscape is an important characteristic for Ireland and future energy developments need

to take this into consideration. In the case of community owned projects or developer-led with

significant stakeholding by residents, the location of the project can be agreed on places with no

strong impact on the landscape. Furthermore, the development of small scale projects near a

community, with the main purpose of providing energy for that community, reduces the need

for big energy grids, If they closely match the existing load in an area they can defer expensive

upgrades and extensions of the network, create islands of security during grid outages, and

contribute to voltage stability [19]. In addition, the development of wind requires less space

than solar or any other renewable sources and turbines are considered to be less intrusive than

power plants.

In Ireland, the emissions from the agriculture sector were 31% in 2012. Considering that an

increase in the number of animals is proposed for the future and that Ireland wants to develop

the agriculture sector even more, it is clear that there is a need for deep decarbonisation of all

the other sectors: transport, industry and residential. For transport this means a shift from fossil

fuels to biofuels and electric cars and for industry it means that the energy used should be low

carbon. With a high potential for development of wind, together with the future increase in

electricity demand, Ireland should work towards developing energy projects from renewable

source/making the most out of its potential for renewable energy sources and gaining

independence from import.

Page | 16

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

We should become

global clean

energy systems

leaders

Denmark first presented in 2012 a strategy to reduce the dependence on fossil fuels and to

develop a green economy, a strategy based in a great part on wind energy. One of the reasons

for this approach is to enable prevention of climate change and in so doing prevent having to

leave a large bill to pay for future generations [12]. Although the reduction of greenhouse

gasses that Denmark is hoping to achieve are not sufficient to slow down global warming, the

government hopes that by taking the lead and showing that it is possible to develop an economy

on clean energy, they will encourage the rest of the world to join global efforts to combat

climate change [12]. As Ireland has the resources necessary, we should follow Denmarks

example and become a world leader in implementing clean energy systems.

8. Our position on Wind Energy

Given the climate

change crisis,

fossil fuels

damaging the

environment and

human health,

and our wind

resource,

Having established:

1. That the issue of climate change and global warming is so acute that, to keep increases

0

in global surface temperature below 2 C, severe reductions in emissions of greenhouse

gases, in particular CO2, must be made immediately;

2. That since fossil fuels are the main source of CO2 emissions and in Ireland, 85% of our

energy is sourced from fossil fuels, there is a requirement that we decrease our use of

fossil fuels in energy production and turn to renewable energy sources;

3. That the use of fossil fuels to produce energy is far more harmful to the environment

and human health than the development of wind energy;

4. That Ireland is the second most windy country in Europe after Scotland and wind energy

can be exploited both on-shore and off-shore;

5. That, using collaborative planning, wind projects can be developed with the acceptance

of and buy-in from local communities;

GEAI supports a GEAI supports the future development of wind energy and considers that the development of

wind energy, both on-shore and off-shore, is an essential part of the decarbonisation of energy

planning process production in Ireland.

for wind projects

However, GEAI believes that wind energy projects must include a fully consultative planning

process involving different stakeholders in the development process; and also must include

genuine benefits for the Irish people and, in the case of on-shore developments, local

communities.

which includes

full consultation

and genuine

benefits for the GEAI fully supports and encourages community ownership of wind energy projects and small

Irish people neighbourhood wind energy projects.

GEAI encourages Government to move effectively towards a collaborative planning approach in

the development of wind energy as a national resource owned by and benefiting the Irish

people.

Finally, GEAI asserts that the thesis defended in this paper summarises the position of Good

Energies Alliance Ireland: The development of wind energy is an essential part of the

decarbonisation of energy production in Ireland but such development must have genuine

benefits for and buy-in from the Irish people.

Page | 17

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

9. References

1

Brower, M. (1992). Cool energy: renewable solutions to environmental problems. MIT press. book on google

Leung, D. Y., & Yang, Y. (2012). Wind energy development and its environmental impact: A review. Renewable and

Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16(1), 1031-1039

3

Stern, N. H. (2006). Stern Review: The economics of climate change (Vol. 30). London: HM treasury.

Jeffrey Sachs, 2014, The Age of Sustainable Development

Lund, H. (2007). Renewable energy strategies for sustainable development. Energy, 32(6), 912-919.

Word Bank: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator

Jacobson, M. Z. (2009). Review of solutions to global warming, air pollution, and energy security. Energy & Environmental

Science, 2(2), 148-173.

8

Jacobson M.Z., Bazouin G., Bauer Z.A.F., Heavey C.C., Fisher E., Hutchinson E.C., Morris S.B., Piekutowski D.J.Y., Vencill

T.A., Yeskoo T.W. (2014), 100% Wind, Water, Sunlight (WWS) All-Sector Energy Plans for the 50 United States

Airtricity: http://www.sseairtricity.com/ie/home/who-we-are/about-us/

10

Green Paper on Energy Policy in Ireland

11

Wolsink, M. (2007). Wind power implementation: the nature of public attitudes: equity and fairness instead of backyard

motives. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 11(6), 1188-1207.

12

The Danish Government, Our Future Energy Report, November 2011

13

Wolsink, M. (2000). Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: institutional capacity and the limited significance of public

support. Renewable energy, 21(1), 49-64.

14

Knopper, L. D., & Ollson, C. A. (2011). Health effects and wind turbines: A review of the literature. Environmental Health,

10(1), 78.

15

Warren, C. R., & McFadyen, M. (2010). Does community ownership affect public attitudes to wind energy? A case study

from south-west Scotland. Land Use Policy, 27(2), 204-213.

16

National Research Council (2007), Environmental impacts of wind-energy projects

17

Jobert, A., Laborgne, P., & Mimler, S. (2007). Local acceptance of wind energy: Factors of success identified in French

and German case studies. Energy policy, 35(5), 2751-2760.

18

Centre for Sustainable Energy (CSE), Garrad Hassan and Partners Ltd., Capener, P. and Bond Pearce LLP, 2007. Delivering

community benefits from wind energy development: a toolkit. Report for the Renewables Advisory Board and DTI,

Department of Trade and Industry, London.

19

Walker, G. (2008). What are the barriers and incentives for community-owned means of energy production and use?.

Energy Policy, 36(12), 4401-4405.

20

American Wind Energy Association (2014). Wind energy helps build a more reliable and balanced electricity portfolio

Page | 18

Wind Energy in Ireland A Position Paper by GEAI

21

Pedersen, E., van den Berg, F., Bakker, R., & Bouma, J. (2009). Response to noise from modern wind farms in The

Netherlands. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 126(2), 634-643.

22

Rideout, K., Copes, R., & Bos, C. (2010). Wind turbines and health. National Collaborating Centre for Environmental

Health February 2013 accessed on line at http://www. ncceh. ca/sites/default/files/Wind_Turbines_Feb_2013. pdf.

23

Erickson, W. P., Johnson, G. D., & Young Jr, D. P. (2005). A summary and comparison of bird mortality from

anthropogenic causes with an emphasis on collisions. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PSWGTR-191, 10291042.

24

Australian Wind Energy Association: http://www.w-wind.com.au/downloads/CFS4Tourism.pdf

25

Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (2013); Energy in Ireland 1990 2012 Report

26

Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland: http://www.seai.ie/

Page | 19

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Conference ReportDocument4 paginiConference ReportGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAI Position Paper On Solar EnergyDocument28 paginiGEAI Position Paper On Solar EnergyGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECO-activity ManualDocument53 paginiECO-activity ManualGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation of GEAI Position Paper On Wind EnergyDocument11 paginiPresentation of GEAI Position Paper On Wind EnergyGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAI - Draft National Adaptation Framework Public Consultation SubmissionDocument15 paginiGEAI - Draft National Adaptation Framework Public Consultation SubmissionGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feasibility Study SummaryDocument1 paginăFeasibility Study SummaryGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Part I. Project Identification and SummaryDocument38 paginiPart I. Project Identification and SummaryGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAI - Renewable Electricity Support Scheme Public Consultation SubmissionDocument15 paginiGEAI - Renewable Electricity Support Scheme Public Consultation SubmissionGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Energy Survey ReportDocument7 paginiEnergy Survey ReportGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fracking in Ireland. Overview October 2014Document2 paginiFracking in Ireland. Overview October 2014Good Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biomass WorkshopDocument3 paginiBiomass WorkshopGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar Energy WorkshopDocument26 paginiSolar Energy WorkshopGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Permaculture. Fighting For A Sustainable LivingDocument23 paginiPermaculture. Fighting For A Sustainable LivingGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shale Gas Extraction: The Next Boom?Document32 paginiShale Gas Extraction: The Next Boom?Good Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- About GEAIDocument2 paginiAbout GEAIGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tamboran PresentationDocument31 paginiTamboran PresentationGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Fracking?Document2 paginiWhat Is Fracking?Good Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law Leitrim CymkDocument1 paginăLaw Leitrim CymkGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report Public Meeting Rathlin Basin Drilling ApplicationDocument13 paginiReport Public Meeting Rathlin Basin Drilling ApplicationGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tamboran Looking For Investment April '13Document2 paginiTamboran Looking For Investment April '13Good Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letter To MEPs Re EIA DirectiveDocument2 paginiLetter To MEPs Re EIA DirectiveGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letter To MEPs Re EIA DirectiveDocument2 paginiLetter To MEPs Re EIA DirectiveGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law Leitrim CymkDocument1 paginăLaw Leitrim CymkGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fossil and Nuclear Energy - A Supply OutlookDocument178 paginiFossil and Nuclear Energy - A Supply OutlookGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law Leitrim CymkDocument1 paginăLaw Leitrim CymkGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fossil and Nuclear Fuels - The Supply OutlookDocument30 paginiFossil and Nuclear Fuels - The Supply OutlookGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Australian Gas Fields - Personal Insights Into The Health Impacts and Limitations of RegulationDocument7 paginiThe Australian Gas Fields - Personal Insights Into The Health Impacts and Limitations of RegulationGood Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cleary Fermanagh Poster 28.01.2013Document1 paginăCleary Fermanagh Poster 28.01.2013Good Energies Alliance IrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Generation Plan - Sri LankaDocument7 paginiGeneration Plan - Sri LankaKawshyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grid-connected PV System for EV Charging StationDocument15 paginiGrid-connected PV System for EV Charging StationLam VuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards Free Carbon-Dioxide and More Sustainable EnvironmentDocument2 paginiTowards Free Carbon-Dioxide and More Sustainable EnvironmentRowan SalemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mitsubishi Gas Turbine 07Document4 paginiMitsubishi Gas Turbine 07Felipe Melgarejo100% (1)

- Internship Report INHOUSE 23decDocument16 paginiInternship Report INHOUSE 23decMohit SinghalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Registered CompaniesDocument6 paginiRegistered Companiessnehil saxenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clean Tech Handbook for Asia PacificDocument348 paginiClean Tech Handbook for Asia PacificfdeadalusÎncă nu există evaluări

- State of The Art and Outlook of Chinese Wind Power IndustryDocument39 paginiState of The Art and Outlook of Chinese Wind Power Industrywangwen zhaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIWE Traiing MaterialDocument5 paginiNIWE Traiing MaterialnmkdsarmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP Transco Metering Protocol - Solar PlantDocument5 paginiAP Transco Metering Protocol - Solar Plantkuchiki86Încă nu există evaluări

- Electric PV PPT New3Document32 paginiElectric PV PPT New3Anushka PagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financing Sources for Energy Projects in Developing CountriesDocument57 paginiFinancing Sources for Energy Projects in Developing Countrieshunter8213Încă nu există evaluări

- Visualizing The 3 Scopes of Greenhouse Gas EmmisionsDocument3 paginiVisualizing The 3 Scopes of Greenhouse Gas EmmisionsKonstantinos NikolopoulosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bahrain WTCDocument12 paginiBahrain WTCvenkatareddy dwarampudiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar farms in France and Germany from ground-mounted and roof systems between 2010-2018Document2 paginiSolar farms in France and Germany from ground-mounted and roof systems between 2010-2018Elias RizkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 paginiDaftar PustakaRizky Ardias DarmawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 2012 Global Green Economy IndexDocument12 paginiThe 2012 Global Green Economy IndexDual Citizen LLCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piepl-Tmills-15-Module Layout-R3-02.08.2022Document1 paginăPiepl-Tmills-15-Module Layout-R3-02.08.2022DIVAKARÎncă nu există evaluări

- My PreliminaryDocument8 paginiMy PreliminaryTripÎncă nu există evaluări

- EV ReportDocument3 paginiEV ReportBavithra KÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar Pavement - A New Emerging TechnologyDocument13 paginiSolar Pavement - A New Emerging TechnologyMauricio Pertuz ParraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated Bibliography-Solar EnergyDocument6 paginiAnnotated Bibliography-Solar Energyapi-355597172Încă nu există evaluări

- Non Conventional Energy Sources PDFDocument1 paginăNon Conventional Energy Sources PDFPRE-GAMERS INC.Încă nu există evaluări

- A Comprehensive Review On Renewable Energy Integration For Combined Heat and Power ProductionDocument38 paginiA Comprehensive Review On Renewable Energy Integration For Combined Heat and Power ProductionKentner Chavez CorreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Energy Systems and Resources ExplainedDocument22 paginiEnergy Systems and Resources ExplainedTayani Tedson KumwendaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar EnergyDocument8 paginiSolar EnergyNadeem ButtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ocean Energy Potential in LuzonDocument21 paginiOcean Energy Potential in LuzonJoshua AbadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Energising A Sustainable Future: Cypark Resources Berhad (642994-H)Document142 paginiEnergising A Sustainable Future: Cypark Resources Berhad (642994-H)wan ismail ibrahim100% (1)

- PD Jun 2021 EnglishDocument180 paginiPD Jun 2021 EnglishsomsangliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solarized Palawan Quotation FormatDocument12 paginiSolarized Palawan Quotation FormatAaronFajardoÎncă nu există evaluări