Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Untitled

Încărcat de

outdash2Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Untitled

Încărcat de

outdash2Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Toronto Torah

Yeshiva University Torah MiTzion Beit Midrash Zichron Dov

Parshat Vayikra/HaChodesh

1 Nisan, 5775/March 21, 2015

Vol. 6 Num. 27

This issue is sponsored by Miriam and Moishe Kesten

in memory of Larry Roth, who was so dedicated to Torah MiTzion

On Sacrifice

Rabbi Baruch Weintraub

This Shabbat, with its two facets,

engages us twice with the world of the

korbanot (sacrifices). First, in the

weekly parshah we begin to read

Vayikra, a book mainly dedicated to

the Temple service in general, and the

detailed laws of the korbanot in

particular. Second, the annual

calendar appends a special reading

HaChodesh HaZeh for the start of the

month of Nisan. Here, too, the main

part of the reading is dedicated to a

korban: the Korban Pesach.

through the shedding of the animals

blood and the burning of its carcass,

its owner would internalize the

punishment that was his due for his

sins, and advance toward repentance.

Ramban offers a second suggestion,

according to what he terms the way

of truth, i.e. Kabbalah. The details

are esoteric, but the general theory

seems to be clear: the korbanot serve

to bring the sacrifice, the sacrificer,

and even the universe, closer to

Hashem.

bringing a korban at Divine command

represents a reversal of roles, and a

profound surrender. Shifting the

destination of korbanot from idols to

Hashem is not only a change of address;

it requires man to abandon his illusion

of control over the Divine realm,

replacing it with a willing acceptance of

the heavenly yoke. The Korban Pesach

does not appease G-d; it fulfills His

commands, differentiating between

those who fulfill them and those who do

not.

It seems, then, that this Shabbat

presents an opportunity to better our

understanding of the central role of

korbanot in the Torah. In quantity, the

laws of korbanot are presented in

much more detailed fashion than

those of Shabbat, for example. In

quality, the Korban Pesach is

connected directly to our foundational

redemption from Egypt (Shemot

12:13), and the korbanot are described

as a pleasing fragrance to

Hashem. (Vayikra 1:9) Why are the

korbanot so important?

According to the third way, we can

readily understand the immense

importance of the korbanot and the

connection of our national birth with

the Korban Pesach. However, the first

two approaches present a challenge.

Why, within Rambams view, do we

assign such importance to an act that is

merely a re-direction? And why,

a c cor d i n g t o th e p sy ch ol ogi cal

explanation offered by Ramban, is there

a need for a Korban Pesach, which does

not atone for sin? I would like to

suggest an understanding which

combines these two approaches, based

on ideas expressed by Rabbi Yosef Dov

Soloveitchik in his Festival of Freedom

[reviewed in the Book Review column in

last weeks Toronto Torah, available at

http://bit.ly/1CrGySJ] .

Abandoning ones hope of manipulating

the metaphysical world might be seen

as an act of weakness; we are

accustomed to judging the strength and

success of individuals and societies by

their power and control. However,

Mishlei 16:32 teaches, One who is slow

to anger is greater than the mighty

man, and the ruler of his spirit is

greater than a conqueror of cities. Or in

the words of our sages, Who is mighty?

He who overcomes his desires. (Avot

4:1)

This question, of course, is not new.

Early sages discussed the reasoning

underlying the korbanot thoroughly,

and we will bring here three of their

main explanations:

Rambam (Moreh HaNevuchim 3:32,

3:46) explains that G-d commanded

us to sacrifice in order to lead us

away from Avodah Zarah. The

common practice was to sacrifice for

the gods, and G-d commanded us to

bring offerings to Him alone, as a

way to reject idolatry and channel

those idolatrous impulses.

Ramban (Vayikra 1:9) finds a reason

for korbanot in human psychology:

The sacrifices in the pagan world were

intended to butter up the gods, or even

to bribe them outright. These were

manipulations of the gods by man; by

offering something the gods wanted

animals, fruit, etc. man could bait the

gods into helping him with his own

goals. One could then contend that

Rambams approach to the korban

presents it as more than an outlet;

The Korban

Pesach taught our

ancestors a greater aspiration than

control of the world around us. The

korban is more than an outlet, or a

means of learning to repent; the korban

is an act of abandoning our attempt to

control G-d, and instead fulfilling His

commands and developing a

relationship. This higher aspiration is

worthy of the Torahs focus on the

details of korbanot, and the Korban

Pesach, seen in this light, is surely as

basic to our Judaism as the Exodus

itself.

bweintraub@torontotorah.com

OUR BEIT MIDRASH

ROSH BEIT MIDRASH

RABBI MORDECHAI TORCZYNER

AVREICHIM RABBI DAVID ELY GRUNDLAND, RABBI JOSH GUTENBERG, YISROEL

MEIR ROSENZWEIG

COMMUNITY MAGGIDEI SHIUR

RABBI ELAN MAZER, RABBI BARUCH WEINTRAUB

CHAVERIM DAR BARUCHIM, DANIEL GEMARA, SHMUEL GIBLON, YOSEF HERZIG, BJ

KOROBKIN, RYAN JENAH, JOEL JESIN, SHIMMY JESIN, AVI KANNER, YISHAI KURTZ,

MITCHELL PERLMUTTER, JACOB POSLUNS, ARYEH ROSEN, DANIEL SAFRAN, KOBY

SPIEGEL, EFRON STURMWIND, DAVID SUTTNER, DAVID TOBIS, EYTAN WEISZ

We are grateful to

Continental Press 905-660-0311

Book Review: The Haggadah of Rabbi Kook

Haggadah shel Pesach: Olat Raayah

Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook

Mossad haRav Kook, Hebrew

1948 ed. http://hebrewbooks.org/11155

New edition: http://bit.ly/1HVBc0V

Also appears in Olat Raayah, Vol. 2

What is in this Haggadah?

This haggadah is composed of two

parts: one part was written as a

commentary to the different parts of the

haggadah, and the rest is collected from

Rabbi Kooks diverse ouevre. The latter

part is marked as likutim.

Despite coming from different sources,

the two parts blend well together. The

likutim add a key component to the

haggadah, since Rabbi Kooks general

approach is to explain the haggadah not

as an independent text, but as part of

broader Torah, expressing the themes

of Judaism as a whole.

Students of Rabbi Kooks thought will

find many links between his haggadah

commentary and ideas he discusses

elsewhere. For example: Rabbi Kook is

known for his belief that all that occurs

is a positive part of the Divine plan. The

fact that good results at the end of a

process indicates that all previous steps

were also good. [See, for example, Orot

haTe shuvah.] Writing on the

haggadah, Rabbi Kook uses this to

describe our national exile in Egypt as

neither punishment nor obstacle, but

part of a Divine plan and a key

element of creating ultimate goodness.

He uses this to explain why the

haggadah begins by detailing our

national disgrace; our lowly beginnings

were the springboard that launched us

toward our ultimate exaltation.

Rabbi Kooks popular theme of

recognizing the value of all people, and

his emphasis upon appreciating both

the physical and spiritual, both play

significant roles in his haggadah

commentary. An ideal example is his

commentary to Koreich, in which he

discusses the union of multiple

aspects of our spiritual lives as

represented by matzah and marror, as

well as the union of Jews whose

actions demonstrate these different

aspects.

Why is this Haggadah different?

Many haggadot split Maggid from the

rest of the Seder, providing a running

commentary on the Maggid text and

then addressing the other parts of the

613 Mitzvot: #431: Loving the Convert

The Torah commands us to be careful in our treatment of

people who convert to Judaism, instructing us to take special

care in avoiding inflicting verbal or financial harm upon

them. (Shemot 22:20 and Vayikra 19:33) Sefer haChinuch

includes these as Mitzvah 63 and 64 in his count of our

biblical commandments. Separately, Devarim 10:19

commands us, You shall love the convert, for you were

converts when you left Egypt. This presents a separate,

positive mitzvah, which Sefer haChinuch lists as the 431st

biblical mitzvah, saying, We must be careful not to pain

them in anyway; rather, we must benefit them and perform

acts of generosity toward them, to the extent appropriate and

possible.

Many commandments governing our relations with other

human beings, but the Torah clearly regards the convert as

special. Rambam (Sefer haMitzvot, Aseh 207) says that this is

because someone who approaches Judaism on her own

initiative achieves a great spiritual level; the Sefer haChinuch

(Mitzvah 431) adds that one who converts to Judaism lacks a

natural support system and needs extra assistance. Rabbi

Avraham Shirman contends that according to Rambam, the

mitzvot of treating a ger with special care apply even before

conversion, when this person has already demonstrated

spiritual greatness.

This mitzvah may explain two challenging talmudic sources:

First, the Talmud (Shabbat 137b) states that the blessing

performed when circumcising a convert blesses G-d who

sanctified us with His mitzvot, and commanded us to

circumcise converts.

Second, the Talmud (Yevamot 47b) states that once a

convert has accepted mitzvot, we do not delay the rest of

the conversion, because we do not delay mitzvot.

Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner

Seder as separate units. In contrast,

Rabbi Kooks commentary portrays the

entire Seder as a process of growth

and elevation, beginning with the

clarion call of Kadesh! [Sanctify!] and

continuing all the way through Nirtzah

[accepted], when we have achieved

the lofty state in which G-d is satisfied

with us. We learn how every element of

the Seder, from the breaking of the

middle matzah to the singing of Hallel,

contributes to our personal and

national elevation. [This haggadah

does not offer detailed commentary on

the text of Hallel and Nirtzah, though.]

A cautionary note

Rabbi Kooks writing can be florid,

making for slow reading. Also, Rabbi

Kooks haggadah commentary

occasi onal ly emp loys te chn i cal

philosophical terminology. Therefore,

study is strongly recommended; one

who picks up this haggadah for the

first time during the Seder will likely

not find it particularly helpful.

There is an English haggadah based

on the writings of Rav Kook, but this

writer has not read it. (http://

amzn.to/1ANyRzf)

torczyner@torontotorah.com

Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner

Both of these sources indicate that there is a mitzvah of

aiding conversion but where does the Torah command us

to help people convert to Judaism? Rabbi Avraham Shirman

explains that given Rambams view that we are to love

converts because of their great spiritual level, perhaps the

mitzvah of loving the convert begins even before the

conversion. This mitzvah of loving the convert is also what

requires us to aid in conversion. (For more on this point, see

Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Berachot 11:7; Zohar haRakia to

Aseh Mem; Dvar Avraham 25; Mishneh Halachot 15:92.)

One might wonder why Jews have historically discouraged

conversion, given the mitzvah of loving the convert. Two

primary reasons may be identified within Jewish tradition:

The Talmud (Yevamot 47b) says to give the conversion

candidate the opportunity to abandon conversion,

because those who convert are difficult for Israel.

Commentators struggle to explain what this difficulty is,

suggesting multiple explanations, including that they err

due to their lack of training in Judaism, and that they

make born Jews look bad for our lack of piety. (See

Rashi and Tosafot to Yevamot 47b and Niddah 13a.)

We are prohibited from causing others to stumble, and

accepting a convert who was insincere would cause

stumbling. As Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook explained

(Daat Kohen 154), either the conversion would be invalid

and cause people to erroneously think of this person as a

Jew, or the conversion would be valid and the insincere

convert would be liable for any sins. The same idea was

expressed by Rabbi Yechiel YaakovWeinberg (Sridei Ish

2:96) and Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (Minchat

Shlomo 1:35:3).

torczyner@torontotorah.com

Visit us at www.torontotorah.com

Biography

Rabbi Yaakov Emden

Rabbi Yair Manas

Rabbi Yaakov Emden, son of Rabbi Tzvi

Ashkenazi (Chacham Tzvi), was born on

June 4, 1697, in Altona. Altona, located

in present-day Germany, was then a

Danish harbour town. Jews were not

permitted to live in Hamburg, Germany,

and they instead settled in Altona. Rabbi

Emden passed away in 1776.

Rabbi Emden studied Talmud with his

father until he married, and became

expert in philosophy, kabbalah, and

grammar. Other than serving as Rabbi of

Emden, Germany for a short period,

Rabbi Emden did not work professionally

as a rabbi; he dealt in jewelry, and later

in life he operated a printing press.

Rabbi Emden is known for the more than

thirty books he wrote and published,

including the Sheelat Yaavetz collection

of responsa, and Mor UKtziah on

Shulchan Aruch. Beyond his writing,

though, Rabbi Emden is known for his

controversies.

Among

Rabbi

Emdens

more

controversial opinions are claims that

Maimonides did not write the Guide for

the Perplexed - because of seemingly

heretical ideas contained therein - and

that the Zohar was a forgery. Also, Rabbi

Emdens opponents accused him of

deviating from the common text in the

siddur that he published. Arguably,

Rabbi Emden is best known for his

conflict

with

Rabbi

Yehonatan

Eybeschutz, in which he accused Rabbi

Eybeschutz of following the false

messiah, Shabbtai Zvi, a charge that has

been much debated without any

definitive conclusion.

Torah and Translation

Against the Kitniyot Custom

Rabbi Yaakov Emden, Mor UKetziah Orach Chaim 453

Translated by Rabbi Josh Gutenberg

Note: The following source is brought for the sake of Torah study,

not practical halachah. For practical halachah, please speak to your Rabbi.

,

,

,

.

(

[ ]

, ) , ,

.

,

.

] ,[

.

.

( )

.

In dire situations, certainly one should

permit to eat all legumes, for even our

master, author of the Tur, who was of

Ashkenazi descent and in whose days

the stringent custom had already begun,

did not follow it and wrote that it is an

excessive stringency which they did not

observe. Implying, that our Ashkenaz

ancestors did not accept [this practice]

in his days (therefore, the annotation to

Rama 453:1, that the Tur originated this

stringency, is incorrect) and it was not

widespread among them. Several

authorities think it is foolish and a

mistaken custom, which does not even

require regret or annulment [in order to

cancel it]. Such is demonstrated by an

explicit talmudic passage (Pesachim

114b) that no one is concerned for Rabbi

Yochanan ben Nuris [ruling that it is

forbidden to eat] rice [on Pesach]. Rava

would specifically seek out beets and

rice for the two cooked foods [on the

Seder plate]. All of the stringencies for

legumes were born and grown from rice

(based on Rabbi Yochanan ben Nuri),

and since the roots have been uprooted,

the plants have dried out by themselves.

I testify regarding my father and mentor,

the Gaon [Chacham Tzvi], how much

that righteous one was pained by this

matter. For the entire holiday of Pesach

he would complain and say: If I had the

strength I would nullify this deficient

custom, which is a stringency that will

result in a leniency and from it will come

destruction and obstacle causing people

to violate the prohibition of actual

chametz. Since the legume species are

not [permissibly] available for the

ymanas@gmail.com

masses to cook and sate themselves,

they must bake more matzah. This is

especially true for the poor and for those

who have large households. They will

There will be no

not have enough dishes to satisfy their

Toronto Torah

hunger, and will be forced to obtain

matzah for their households and as

next week

sustenance for their adolescents. Due to

this, they are not scrupulous with the

dough as is necessary and required.

They make it very large, and they delay

a lot [before baking it]. It is probable

Look for our

that they will violate a prohibition whose

Pesach Seder

punishment is karet, G-d forbid. The matzah is also very expensive for them and

Companion

not everyone can afford to make enough for his household. They are not able to find

even enough leavened bread during the year. Legumes can be found cheaper

in your shul

without exerting any effort, permissibly. This prevents joy on the holiday, for a

stringency that has neither taste nor smell.

Visit us at www.torontotorah.com

,

,

:

,

,

,

,

.

,

.

.

,

,

,

,

.

This Week in Israeli History: 3 Nisan, 1966

Launch of Israeli Educational Television

Yisroel Meir Rosenzweig

3 Nisan is Monday

Like many Israeli cultural institutions, Israeli Educational

Television [IETV] was born out of a partnership between the

Israeli government and the Batsheva de Rothschild Fund.

The Rothschild Fund helped provide the initial funding to

launch the network, before handing it over to the Israeli

Ministry of Education. The creation of IETV , which first

broadcast programming on 3 Nisan (March 24) 1966,

represented the beginning of television broadcasts in Israel.

In its original form, IETV was billed as a way to supplement

curricular material from school in the home. As such, the

vast majority of the programming was purely educational,

ranging from chemistry for beginners to English language

programming. In the beginning years of IETV, televisions

were distributed to schools to help assess the quality of the

programming. Over time, however, more entertainmentfocused programming was introduced during daytime

hours, affecting the overall educational character of the

network. In recent years, there has been a shift toward

returning to programming that is more educational in nature.

Currently, IETV broadcasts over 200 hours of programming

weekly spread across three separate channels. Until recently,

it was only available through subscription. However, as of

2012, the Knesset Economics Committee made IETV available

for free through the public access digital TV broadcasting

system. Israel has gradually been replacing many of its

conventional radio broadcast methods with satellite and

terrestrial digital broadcasting.

In Spring 2015, new reforms will, among other things, create a

dedicated childrens channel. Many of the networks recent

shows can be found on their YouTube channel. Their popular

shows include Ma Pitom, Rechov Sumsum, and Bli Sodot.

yrosenzweig@torontotorah.com

Weekly Highlights: Mar. 21 Mar. 27 / 1 Nisan 7 Nisan

Time

Speaker

Topic

Location

Special Notes

9:30 AM

R David Ely Grundland

Torah Temimah

Shaarei Shomayim

10:30 AM

Yisroel Meir Rosenzweig

Meshech Chochmah

Clanton Park

Before minchah

R Mordechai Torczyner

Daf Yomi

BAYT

Rabbis Classroom

After minchah

R Mordechai Torczyner

Gemara Avodah Zarah

BAYT

West Wing Library

8:45 AM

R Mordechai Torczyner

When Questions Matter

More Than Answers

TCS

(Aish Thornhill)

Breakfast

8:45 AM

R Josh Gutenberg

Contemporary Halachah

BAYT

Third floor

9:15 AM

R Shalom Krell

Kuzari

Zichron Yisroel

with light breakfast

8:00 PM

R Mordechai Torczyner

When Questions Matter

More Than Answers

532 Arlington Ave.

Toronto

with

The Village Shul

8:30 PM

R David Ely Grundland

Gemara: Mind, Body, Soul

Shaarei Shomayim

Beit Midrash

Mar. 20-21

Sun. Mar. 22

Mon. Mar 23

8:00 PM

R David Ely Grundland * R Josh Gutenberg * Yisroel Meir Rosenzweig

Haggadah Night at Shaarei Tefillah

Tues. Mar 24

1:30 PM

8:00 PM

R Mordechai Torczyner

Book of Job: End of Round 1 Shaarei Shomayim

R David Ely Grundland * R Josh Gutenberg * Yisroel Meir Rosenzweig * R Mordechai Torczyner

Haggadah Night at BAYT

Wed. Mar. 25

10:30 AM

R Mordechai Torczyner

Sociology and the Synagogue

Beth Emeth

12:30 PM

R Mordechai Torczyner

Ransoming Captives

from ISIS

SLF

2300 Yonge St.

R Mordechai Torczyner

The Book of Yehoshua:

Dividing the Land

49 Michael Ct.

Thornhill

R Mordechai Torczyner

Advanced Shemitah

Yeshivat Or Chaim

Week 5 of 5

Lunch served

RSVP to

jonathan.hames@slf.ca

Thu. Mar. 26

1:30 PM

Fri. Mar. 27

10:30 AM

For Women Only

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- CATCH 22 Complete TextDocument157 paginiCATCH 22 Complete Textmicksoul100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The List of The Tribes in Revelation 7 AgainDocument18 paginiThe List of The Tribes in Revelation 7 AgainIustina și ClaudiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Introduction to Biblical HebrewDocument15 paginiIntroduction to Biblical HebrewJody C. McLeary100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- A ... Marathon BeginsDocument23 paginiA ... Marathon BeginsDaiszyBaraka100% (6)

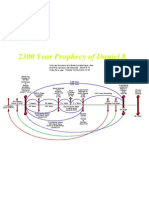

- 2300 Day Prophecy-ColorDocument1 pagină2300 Day Prophecy-ColorDominique Lim YanezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Jehovah WitnessesDocument12 pagini5 Jehovah WitnessesDarren Alex Bright100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- How To Overcome FornicationDocument3 paginiHow To Overcome FornicationEbenezer Agyenkwa ColemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777Document4 paginiParashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 17 - Age of Enlightenment OutlineDocument12 paginiChapter 17 - Age of Enlightenment OutlineEmily FeldmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nubian Moses, Ethiopian/Eritrean Exodus, Arabian SolomonDocument31 paginiNubian Moses, Ethiopian/Eritrean Exodus, Arabian SolomonBernard LeemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fiqh of Salah Notes MadinataynDocument139 paginiFiqh of Salah Notes MadinataynrashadhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dictionaries of Hebrew and Greek WordsDocument956 paginiDictionaries of Hebrew and Greek Wordsgheorghe3Încă nu există evaluări

- Decalogue ReflectionDocument2 paginiDecalogue ReflectionMagat AlexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shofar What The Jewish Laws?Document13 paginiShofar What The Jewish Laws?Arthur FinkleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trude Dothan-The Philistines and Their Material Culture-Israel Exploration Society (1982)Document325 paginiTrude Dothan-The Philistines and Their Material Culture-Israel Exploration Society (1982)Xavier75% (4)

- Lessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi RommDocument5 paginiLessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi Rommoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- 879645Document4 pagini879645outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocument28 paginiChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- 879547Document2 pagini879547outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- The Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)Document4 paginiThe Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocument2 paginiShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- The Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny JoelDocument2 paginiThe Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny Joeloutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- The Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli BelizonDocument3 paginiThe Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli Belizonoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Flowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra SchwartzDocument2 paginiFlowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra Schwartzoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- 879510Document14 pagini879510outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Performance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel ZylbermanDocument6 paginiPerformance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel Zylbermanoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Consent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. SchacterDocument3 paginiConsent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacteroutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Reflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of BrachosDocument3 paginiReflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of Brachosoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- What Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery JoelDocument3 paginiWhat Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery Joeloutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- I Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah NagarpowersDocument2 paginiI Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah Nagarpowersoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Why Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of IsraelDocument5 paginiWhy Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of Israeloutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocument2 paginiShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Chag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. JoelDocument2 paginiChag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Experiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem PennerDocument3 paginiExperiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem Penneroutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Lessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus ProcessDocument3 paginiLessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus Processoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- A Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua FassDocument3 paginiA Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua Fassoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Nasso: To Receive Via Email VisitDocument1 paginăNasso: To Receive Via Email Visitoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- The Power of Obligation: Joshua BlauDocument3 paginiThe Power of Obligation: Joshua Blauoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Kabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther JoelDocument2 paginiKabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther Joeloutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Yom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel DavisDocument1 paginăYom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davisoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Torah To-Go: President Richard M. JoelDocument52 paginiTorah To-Go: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- 879399Document8 pagini879399outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- José Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37Document16 paginiJosé Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- 879400Document2 pagini879400outdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Hymn to Labor Poem Celebrates Filipino Work EthicDocument1 paginăHymn to Labor Poem Celebrates Filipino Work EthicDianne Mendoza100% (1)

- Muslim Army of Jesus & Mahdi & Their 7 SignsDocument13 paginiMuslim Army of Jesus & Mahdi & Their 7 SignsAbdulaziz Khattak Abu FatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arab Nationalism PDFDocument36 paginiArab Nationalism PDFApurbo Maity100% (2)

- Abu Atallah - Answers For Muslims - Has The Bible Been Corrupted PDFDocument2 paginiAbu Atallah - Answers For Muslims - Has The Bible Been Corrupted PDFmsdfli0% (1)

- Echo Mime 2Document2 paginiEcho Mime 2api-389449997Încă nu există evaluări

- Kwetu Pazuri1Document5 paginiKwetu Pazuri1kastimoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investigation Into Child Protection in Religious Organisations and SettingsDocument39 paginiInvestigation Into Child Protection in Religious Organisations and SettingssirjsslutÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class of 2009!: by Michael Howland, Youth PastorDocument4 paginiClass of 2009!: by Michael Howland, Youth PastorJohn C StarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Aspects of The Crucifixion of Jesus ChristDocument19 paginiMedical Aspects of The Crucifixion of Jesus ChristJimmellee EllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heaven Is Hotter Than HellDocument12 paginiHeaven Is Hotter Than HellA. HeraldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islam ReligionDocument5 paginiIslam Religionjaknoll7341Încă nu există evaluări

- End of Time PT 2 PDFDocument87 paginiEnd of Time PT 2 PDFJohn KingsÎncă nu există evaluări

- KissingerDocument4 paginiKissingerAlperUluğÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Study Hebrew by MartinDocument6 paginiWhy Study Hebrew by MartinStephen HagueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romans 2.1-29Document24 paginiRomans 2.1-29Ardel B. CanedayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scavenger HuntDocument4 paginiScavenger Huntapi-249038203Încă nu există evaluări