Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Case Report: Implementation of Measurement Instruments in Physical Therapist Practice: Development of A Tailored Strategy

Încărcat de

NelsonRodríguezDeLeónTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Case Report: Implementation of Measurement Instruments in Physical Therapist Practice: Development of A Tailored Strategy

Încărcat de

NelsonRodríguezDeLeónDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Case Report

Implementation of Measurement

Instruments in Physical Therapist

Practice: Development of a

Tailored Strategy

J.G. Anita Stevens, Anna J.M.H. Beurskens

Background and Purpose. The use of measurement instruments has become

a major issue in physical therapy, but their use in daily practice is infrequent. The

aims of this case report were to develop and evaluate a plan for the systematic

implementation of 2 measurement instruments frequently recommended in Dutch

physical therapy clinical guidelines: the Patient-Specific Complaints instrument and

the Six-Minute Walk Test.

Case Description. A systematic implementation plan was used, starting with a

problem analysis of aspects of physical therapist practice. A literary search, structured

interviews, and sounding board meetings were used to identify barriers and facilitators. Based on these factors, various strategies were developed through the use of a

planning model for the process of change.

Outcomes. Barriers and facilitators were revealed in various domains: physical

therapists competence and attitude (knowledge and resistance to change), organization (policy), patients (different expectations), and measurement instruments (feasibility). The strategies developed were adjustment of the measurement instruments,

a self-analysis list, and an education module. Pilot testing and evaluation of the

implementation plan were undertaken. The strategies developed were applicable to

physical therapist practice. Self-analysis, education, and attention to the practice

organization made the physical therapists aware of their actual behavior, increased

their knowledge, and improved their attitudes toward and their use of measurement

instruments.

J.G.A. Stevens, PT, MSc, is Researcher and Teacher, Center of

Research Autonomy and Participation of People With Chronic Illnesses, Department of Physiotherapy, Zuyd University, Nieuw

Eyckholt 300, PO Box 550, 6400

AN Heerlen, the Netherlands. Address all correspondence to Ms

Stevens at: a.stevens@hszuyd.nl.

A.J.M.H. Beurskens, PT, PhD, is Associate Professor, Center of Research Autonomy and Participation of People With Chronic

Illnesses, Department of Physiotherapy, Zuyd University.

[Stevens JGA, Beurskens AJMH.

Implementation of measurement

instruments in physical therapist

practice: development of a tailored strategy. Phys Ther. 2010;

90:953961.]

2010 American Physical Therapy

Association

Discussion. The use of a planning model made it possible to tailor multifaceted

strategies toward various domains and phases of behavioral change. The strategies

will be further developed in programs of the Royal Dutch Society for Physical

Therapy. Future studies should examine the use of measurement instruments as an

integrated part of the process of clinical reasoning. The focus of future studies should

be directed not only toward physical therapists but also toward the practice organization and professional associations.

Post a Rapid Response to

this article at:

ptjournal.apta.org

June 2010

Volume 90

Number 6

Physical Therapy f

953

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

onitoring the health status

of patients through the use

of outcome measures is considered to be an aspect of good clinical practice in physical therapy.13

The clinical guidelines of the Royal

Dutch Society for Physical Therapy

recommend the use of measurement

instruments. Until now, this recommendation has been implemented in

a passive way by mailing the clinical

practice guidelines containing the

measurement instruments. Despite

the overall positive attitude of physical therapists, the daily use of outcome measures in physical therapist

practice is remarkably low.2,4 8

In Europe and Australia, implementation is a common term for what in

the United States is called knowledge translation or exchange. In this

article, the term implementation,

which means a systematic process

in which innovations or changes of

proven value become structurally

embedded in professional practice,

was used. It is well known that passive implementation strategies are

not effective.9,10 Systematic reviews

of the effectiveness of implementation interventions have shown that

strategies should be targeted toward

specific barriers to and facilitators of

change that have been assessed in a

thorough problem analysis of the target group and setting.9,1118 Although

education is an important strategy,

implementation should not be restricted to educational interventions

for individual health professionals

only. Factors concerning practice

policy and organization, patients,

Available With

This Article at

ptjournal.apta.org

Audio Abstracts Podcast

This article was published ahead of

print on April 22, 2010, at

ptjournal.apta.org.

954

Physical Therapy

Volume 90

and the measurement instruments

themselves also are important.4,12

The Dutch Scientific College of Physiotherapy of the Royal Dutch Society

for Physical Therapy has made a systematic approach to the implementation of outcome measures in daily

practice a focal point of its policy.

The aims of this case report were to

develop and evaluate a systematic implementation plan for the use of 2

measurement instruments frequently

recommended in Dutch physical

therapy clinical guidelines: the PatientSpecific Complaints (PSC) instrument,19 which is comparable to the

Pain-Specific Functional Scale,20 and

the Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT).21

To meet our aims, we sought answers

to 2 questions:

1. Which barriers and facilitators

contribute to the use of the PSC

and 6MWT in physical therapist

practice?

2. Which implementation strategies

can be tailored to these barriers

and facilitators and applied to

physical therapist practice?

Target Setting

The implementation plan was aimed

at physical therapists in private practice in the community. This group is

the largest group of physical therapists in the Netherlands; they are easily accessible and are not restricted

by complicated and formal institutional rules. It also appears that these

physical therapists use fewer measurement instruments than their colleagues in hospitals and other

institutions.7

Development and

Application of the Process

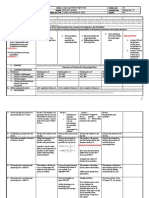

As a guideline for a systematic approach, the implementation model

of Grol et al10 was used. The 5 steps

in this model and the methods used

in this case report are shown in the

Figure.

Number 6

Step 1: Proposal for

Improvement

We focused on the implementation

of 2 easily applicable measurement

instruments that are frequently recommended in Dutch physical therapy guidelines. The first instrument

was the PSC, a Dutch instrument that

is comparable to the Pain-Specific

Functional Scale.19,20 In both instruments, patients must list 3 activities

and score them. Differences are the

scoring method (visual analog scale

versus numerical rating scale), the

time frame on which the score is

based (1 week versus 1 day), and the

availability of a sample activity list in

the PSC to help patients identify

their main complaint. The second instrument was the 6MWT, which is

used to assess the aerobic exercise

capacity of a patient by measuring

the walking track length in 6

minutes.21

Step 2: Problem Analysis

To obtain a complete and valid overview of relevant barriers and facilitators, we used various methods to collect information. First, a literature

search of the PubMed and Cochrane

databases was carried out to identify

studies about barriers and facilitators

in the use of measurement instruments and clinical guidelines. From

this information a topic list was formulated (the list is available on request from the authors). Second,

physical therapists in several private

practices were interviewed. We

searched for a wide variety in terms

of expertise and number of employees and considered the use of clinimetrics (purposive sampling).

The

semistructured

interviews

(45 60 minutes) were digitally audiotaped, summarized, and member

checked by the physical therapists.

The interviews started with general

inquiries on the following themes:

information about the practice, patient categories, and measurement

instruments used. Thereafter, open

June 2010

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

Figure.

Implementation model of Grol et al10 and the methods used in this case report. KNGFKoninklijk Nederland Genootschap voor

Fysiotherapie (Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy).

questions were asked about perceived barriers and facilitators in the

use of measurement instruments in

daily practice. At the end of each

interview, the topic list was presented to the interviewees, and additional relevant items could be indicated. The barriers and facilitators

identified were ordered in various

domains: the physical therapist, the

organization, patients, and the measurement instruments themselves.

The number of interviews was estimated at between 15 and 20, and the

interviews were stopped when a saturation of data was reached.22

Step 3: Development of

Implementation Strategies

The information from step 2 guided

the selection of both the type and

June 2010

the specific content of the implementation strategies developed; a

planning model for the process of

change was used.10,16 In addition, a

literature survey on how to select

and tailor strategies to the information from the problem analysis was

performed. Until now, not many implementation studies have been

based on a problem analysis. Therefore, studies about the effect of implementation on general health were

used. The results from both the literature search and the interviews were

discussed with the project group

(experts in the field of guideline implementation) and a sounding board

(the interviewed physical therapists).

Subsequently, implementation strategies were selected and developed.

Steps 4 and 5: Testing and

Evaluation of the

Implementation Plan

In the literature, recommendations

were made about testing interventions initially in small groups, in

which active education and professional support seemed to be effective in improving physical therapists

attitudes and adherence.4,23,24 Therefore, pilot testing of the implementation plan was undertaken with 2

groups of physical therapists from 4

physical therapist practices. The

evaluation focused on feasibility and

readjustment of the strategies developed. The results of the first pilot

program were used to make adjustments in the second pilot program. It

was not our intention to evaluate the

effectiveness of the strategies, but the

Volume 90

Number 6

Physical Therapy f

955

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

Table 1.

Summary of Barriers to and Facilitators of the Use of Measurement Instruments Reported in the Interviews

Domain

Barriers

Facilitators

Physical therapist

Competence

Attitude

Lack of knowledge, education, routine, and

experience

Sufficient knowledge and education

Diagnosis focused on ICFa domain: body

functions

Measurement instruments are already used in

daily routine

Resistance to change

Readiness to change

No conviction of additional value on the plan

of care

Positive attitude toward the use of

measurement instruments

Being overloaded with information

Conviction of contribution to quality of physical

therapy care

Headstrong in own working method

Defining therapy outcome otherwise

Lack of confidence in own skills

Organization

Practice

Takes too much time

Patient computer system

No financial compensation

Colleagues

Patient

Absence of practice policy

Presence of practice policy

Lack of discussions, meetings, and feedback

from colleagues

Regular meetings and feedback from colleagues

No adherence to the agreements made

Innovative team and cooperative colleagues

Different expectations and preferences: needs

no measurement instruments, wants only

therapy, and puts pressure on therapist

Patient wants objectives to evaluate outcome of

therapy

Linguistic problems and lack of understanding

Measurement instrument

Poor availability

Good availability

Difficult choice

Feasibility: extensive, difficult interpretation,

and unclear instructions

a

ICFInternational Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

therapists were asked whether their

knowledge, attitudes, and use of measurement instruments had changed.

Outcome

Step 2: Problem Analysis

All of the physical therapists who

were invited for the interviews attended the interviews. After 11 interviews with 13 physical therapists, a

saturation of data was reached, and

the interviewing was stopped. The

physical therapists, whose ages

ranged from 22 to 54 years (median43), were interviewed in the

southern region of the Netherlands.

Their working experience varied

from 2 to 30 years (median21), and

956

Physical Therapy

Volume 90

the number of colleagues in the practice varied from 1 to 11 (median6).

The interviewed physical therapists

specialized in different areas. The report of the interview was sent to

each therapist for member checking, and the reports were all in

agreement.

The 13 therapists indicated that they

were familiar with the PSC and

6MWT, but less than half of them

indicated that they used these measures. Almost all interviewed physical therapists were motivated to use

the instruments and were convinced

of the additional value. Barriers and

Number 6

facilitators reported in the interviews are summarized in Table 1.

In the sounding board, discussions

about the identified barriers and facilitators took place. During these

discussions, some physical therapists

were very honest and admitted that

they did not use the measurement

instruments as often as they claimed.

Because of the gap between claiming

to use and actually using the instruments, the physical therapists made

a commitment to use the PSC and

6MWT for 1 month and then discuss

their experiences in a subsequent

meeting. In the second meeting,

they indicated that the instruments

June 2010

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

Table 2.

Planning Model for the Process of Changea

Domain

Phase of Behavioral Change and

Implementation Goals

Implementation Strategies

Physical therapist

Competence

Orientation:

Awareness, interest, and involvement

Insight:

Increasing knowledge and understanding

Attitude

Insight:

Insight into own working method

Acceptance:

Positive attitude and motivation

Intention and decision to change

Change:

Confirmation of the benefit

Organization

Education:

Homework tasks

Practical training and role playing

Self-analysis list:

Increasing awareness, self-reflection, and insight

into own working method

Education:

Discussions about resistance, advantage, and

added value of clinimetrics

Coaching style, own responsibility, individual

learning goals, and interactions with colleagues

Insight:

Insight into own working method

Self-analysis list:

Insight into practice policy

Acceptance:

Positive attitude and motivation

Intention and decision to change

Education:

Discussions and agreements with colleagues,

development of practice policy, and formulation

of learning and practice goals

Change:

Implementation in daily practice

Preservation of change:

Integration in daily routines

Anchoring in the organization

Measurement instrument

KNGF:

Dissemination by publications

Offering education possibilities

Insight:

Increasing knowledge and understanding

Acceptance:

Positive attitude and motivation

Change:

Implementation in daily practice

KNGF:

Embedding in future electronic patient dossier

Adjustments in PSC and 6MWT:

Increasing feasibility and simplifying instructions

Extending PSC activity lists

Education:

Practical training and homework tasks

Formulation of practice policy

Preservation of change:

Integration in daily routines

Anchoring in the organization

a

The developed implementation strategies are based on various domains and phases of behavioral change, each with specific implementation goals.10,16

KNGFKoninklijk Nederland Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie (Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy), PSCPatient-Specific Complaints instrument,

6MWTSix-Minute Walk Test.

were useful in daily practice. For

example, 1 therapist previously

thought that he could not use the

instruments because his patients

only wanted therapy and no measurements; however, the patients appreciated the use of the measurement instruments and asked him to

use them regularly to monitor their

progress. These experiences led to

the identification of new barriers and

facilitators, which made the implementation a cyclic process.

June 2010

Step 3: Development of

Implementation Strategies

There is no consensus about the

best general implementation strategy.9,17,25,26 It is clear, however, that

active, multifaceted strategies tailored to a problem analysis are the

most effective.13,16,18,24 In addition,

different models of behavioral

change are recommended, but there

is no agreement about which model

should be used.10,12,14 16 Grol and

colleagues10,16 described a planning

model for the process of change in

which different theories of behavioral change are integrated to induce

changes in professional behavior. Table 2 shows various domains, phases

of behavioral change (orientation, insight, acceptance, change, and preservation of change), and specific implementation goals. On the basis of

this information, we tailored the outcome of the problem analysis to the

appropriate implementation strategies. The definitive strategies, resulting from the project group and

sounding board discussions, were

Volume 90

Number 6

Physical Therapy f

957

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

critically evaluated and readjusted

several times. An overview of these

strategies is shown in Table 2.

To improve the feasibility of using

the PSC and 6MWT, we made several

adjustments:

The instructions were slightly adjusted to improve interpretation.

The original PSC was developed for

patients with low back pain, and

the sample activity list contained

activities with which only those patients would have difficulties. A list

of sample activities was made for

patients with other disorders.

The visual analog scale of the original PSC was replaced with an 11point numerical rating scale. Practical use by the physical therapists

and information from the literature

revealed that this scoring method

was more feasible for some (older)

patients.27 Changing the visual analog scale to a numerical rating scale

did not change the principle of the

test; the scoring methods are highly

correlated.28 A numerical rating

scale also is used in the PainSpecific Functional Scale.20

A self-analysis list was developed to

provide insight into and selfawareness of barriers and phases of

behavioral change. This list was

based on a questionnaire on the selfreported use of outcome measures in

physical therapy and was obtained,

along with other items, from the

problem analysis.7 It contained 3 sections with questions concerning the

phases of change for the physical

therapist, the organization and its

policy, and an inventory of the actual

use of measurement instruments in

daily practice. A few examples of

questions from sections 1 and 2,

rated on a Likert scale, are shown in

the Appendix. The self-analysis list

was pretested by the physical therapists of the sounding board and was

used as a guide for the education

module.

958

Physical Therapy

Volume 90

An education module focusing on

the physical therapist and the practice organization was developed.

The aims of the education module

were to provide insight into the use

of measurement instruments and

phases of behavioral change, to optimize the use of the PSC and 6MWT

in the process of clinical reasoning,

and to fit the use of the PSC and

6MWT to practice policy. The education module consisted of 3 sessions of 2.5 hours. The first 2 sessions were planned to take place

within 1 month, and the last session

was planned to take place after 2

months. The program was not completely determined in advance but

was tailored to the professionals. Active teaching methods, such as discussion and role playing, were used

in a coaching style instead of a teaching style. We expected the attendees

to show an active learning attitude,

initiative, and responsibility.

Steps 4 and 5: Testing and

Evaluation of the

Implementation Plan

Pilot testing and evaluation of the

implementation plan were undertaken. The adjusted instruments, the

self-analysis list, and the education

program were tested with 2 groups

of physical therapists from 4 private

practices in the community. The first

group consisted of colleagues from

the same practice (n11); the second group consisted of colleagues

from 3 different practices (n10).

After each session, the process and

the program were evaluated orally;

after the third session, an evaluation

form was filled out.

The strategies developed could be

applied to physical therapist practice. The evaluation of the adjusted

measurement instruments was positive. The adjusted instructions were

easier to interpret, and the additional

activity lists were useful for determining treatment goals. The selfanalysis list appeared to be valuable

Number 6

because physical therapists became

aware of their own barriers in daily

practice. The link with their phases

of behavioral change was revealing

and stimulated them to use the instruments in daily practice. Working

with heterogeneous groups made it

difficult to accommodate the individual barriers of the physical therapists

but, on the other hand, they could

learn from one another.

After the evaluation of the first pilot

education program, the second program was adjusted at several points.

The program became more fixed in

advance. In the first session, attendees began to devise a practice policy.

Individual learning goals were discussed, and homework tasks were

checked. More time was allocated

for practical rehearsal of the tests.

The outline of the final education

program is shown in Table 3.

All of the physical therapists appreciated the active teaching methods,

discussions, and role playing during

training. Developing a practice policy was an issue of major importance, especially for the preservation

of change. During busy daily practice, the therapists never took the

time to discuss these matters.

The physical therapists indicated

that they were interested in practicing with other instruments besides

the PSC and 6MWT and would appreciate sets of short, feasible, and

methodologically sound instruments. At the last meeting, most

physical therapists indicated that

they actually used both instruments.

Discussion

In this report, we have shown that it

is possible to develop and evaluate a

systematic implementation plan for

the use of 2 measurement instruments. A thorough analysis was used

to identify practical barriers and facilitators. In the interviews and discussions, we could continue asking

June 2010

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

Table 3.

Outline of the Education Programa

Day

1

Main Issues

Goals

Working Methods

Introduction

Explicating expectations of therapists:

active learning attitude, responsibility,

initiative, active teaching methods, and

coaching style

Plenary

Self-analysis list

Insight into own working method and

phase of behavior

Individual

Individual learning goals and practice

policy

Responsibility for own learning process in

professional and practice organization

domains

Working group of 3 or 4 people

Advantages and disadvantages of

PSC and 6MWT

Insight and acceptance

Plenary

Training on PSC: clarification of the

patients main complaint

Increasing knowledge and practical skills

Working group of 3 or 4 people

Homework on PSC

Using PSC in practice for the next month

Plenary

Evaluation of the session

Reflection

Plenary

Results of self-analysis list

Insight on working method and phase of

behavior

Presentation

Evaluation of homework task

Insight and acceptance

Plenary

Training on 6MWT: standardization

and interpretation

Knowledge and practical skills

Working group of 3 or 4 people

Use of measurement instruments in

practice policy

Integration in the practice organization to

obtain (or preserve) change

Working group of 3 of 4 people

Homework on 6MWT

Using 6MWT in practice for the next 2 mo

Plenary

Evaluation of the session

Reflection

Plenary

Evaluation of homework task

Insight and acceptance

Plenary

Theory of clinimetrics

Insight and knowledge

Lecture

Step-by-step plan to search for other

measurement instruments

Transfer to the use of other instruments

Lecture

Evaluation of practice policy

Integration in the practice organization to

obtain (preserve) change

Working group of 3 or 4 people

Integration of instruments in clinical

reasoning and daily practice

Preservation of behavioral change

Plenary

Written and oral evaluations of total

education module

Reflection

Plenary and individual

PSCPatient-Specific Complaints instrument, 6MWTSix-Minute Walk Test.

about underlying thoughts and possible solutions and strategies. In this

way, the problem analysis produced

a larger amount of information than

earlier reports, in which only written

inquiries were used.4 8,29 31 The revealed factors matched the barriers

and facilitators described in the

literature.4,6 8,29,30,32

Many studies2,4 8,14,29 32 have focused on identifying the extent of

use of measurement instruments as

well as factors that affect that use.

June 2010

We took the additional steps of developing various strategies based on

these factors and evaluating their applicability in a pilot program in several physical therapist practices. The

involvement of a sounding board

during the development phase guaranteed interest in and acceptance of

the implementation strategies by the

target group.12,14,15

Starting education with self-analysis

provides therapists with the opportunity to formulate their own learn-

ing goals, and trainers can tailor strategies to the professionals as well as

the organization. This approach

has been recommended in other

studies.13,18

Using the planning model of Grol

and colleagues10,16 for the process of

change, we were able to tailor multifaceted strategies to various barriers and phases of behavioral change.

In this way, a change in behavior was

initiated. The physical therapists indicated that they used the measure-

Volume 90

Number 6

Physical Therapy f

959

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

ment instruments more often, and

they were convinced that doing so

contributed to the process of clinical reasoning. For the preservation

of change, more time is needed.

It is evident that quality improvements should start with small, simple

projects.23 This case report involved

a small group of selected physical

therapists in the southern region of

the Netherlands; therefore, generalization of the results is unjustifiable.

Further studies and additional designs with other measurement instruments are needed to evaluate the

effects of implementation strategies.

Our recommendations for the policy

of the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy are as follows. First, information about measurement instruments should be disseminated

through publication in professional

journals, newsletters, and guidelines.

This strategy represents the orientation phase, in which awareness of

the existence and use of measurement instruments is an important issue. The information should not be

restricted to the measurement instruments alone but also should focus on

how to use and interpret the results

of the instruments in daily practice.

Second, educational opportunities

should be offered for physical therapists to increase their knowledge

and skills regarding the use of these

and other measurement instruments

in the process of clinical reasoning,

with attention to behavioral change.

This education should be included

in mainstream physical therapist

schools. Third, the measurement instruments should be embedded in

the future electronic patient dossier.

The actual use of measurement instruments should not be the only objective in implementation programs.

The integration of the instruments in

the process of clinical reasoning is of

major importance. Therefore, future

programs should focus not only on

960

Physical Therapy

Volume 90

the physical therapist but also on the

practice organization and professional associations.

Both authors provided concept/idea/project

design, writing, and project management.

Ms Stevens provided data collection and

analysis. Dr Beurskens provided fund procurement and facilities/equipment.

The authors are grateful to members of

the project group (Dr Rob de Bie, Dr Erik

Hendriks, Mr Pieter Wolters, Dr Raymond

Swinkels, Mrs Anja van den Donk, and Mr

John Meijers) and the sounding board (the

physical therapists interviewed).

This work was funded by the Dutch Scientific

College Physiotherapy of the Royal Dutch

Society for Physical Therapy (TD/2008/01).

This work, in part, was presented at the Annual Congress of the Royal Dutch Society for

Physical Therapy; November 9, 2007; Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

This article was received March 30, 2009, and

was accepted February 24, 2010.

DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20090105

References

1 Glasziou P, Irwig L, Mant D. Monitoring in

chronic disease: a rational approach. BMJ.

2005;330:644 648.

2 Haigh R, Tennant A, Biering-Sorensen F,

et al. The use of outcome measures in

physical medicine and rehabilitation

within Europe. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:

273278.

3 Jette DU, Bacon K, Batty C, et al. Evidencebased practice: beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of physical therapists.

Phys Ther. 2003;83:786 805.

4 Abrams D, Davidson M, Harrick J, et al.

Monitoring the change: current trends in

outcome measure usage in physiotherapy.

Man Ther. 2006;11:46 53.

5 Leemrijse CJ, Plas GM, Hofhuis H, van den

Ende CH. Compliance with the guidelines

for acute ankle sprain for physiotherapists

is moderate in the Netherlands: an observational study. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:

293299.

6 Maher C, Williams M. Factors influencing

the use of outcome measures in physiotherapy management of lung transplant

patients in Australia and New Zealand. Physiother Theory Pract. 2005;21:201217.

7 Van Peppen RP, Maissan FJ, Van Genderen

FR, et al. Outcome measures in physiotherapy management of patients with

stroke: a survey into self-reported use, and

barriers to and facilitators for use. Physiother Res Int. 2008;13: 255270.

Number 6

8 Pisters M, Leemrijse C. Het gebruik van

aanbevolen meetinstrumenten in de fysiotherapiepraktijk. Weten is nog geen meten! [The use of measurement instruments

in physiotherapy practice. Knowing it

isnt measuring it!] Nederlands Tijdschrift

voor Fysiotherapie. 2007;5:176 180.

9 Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, et al.

Changing provider behavior: an overview

of systematic reviews of interventions.

Med Care. 2001;39(8 suppl 2):112145.

10 Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M. Improving

Patient Care: The Implementation of

Change in Clinical Practice. Edinburgh,

Scotland: Elsevier Butterworth Heineman;

2005.

11 Grimshaw JM, McAuley LM, Bero LA, et al.

Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of

quality improvement strategies and programmes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:

298 303.

12 Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in

health care. JAMA. 2003;289:1969 1975.

13 Bosch M, van der Weyden T, Wensing MG,

Grol R. Tailoring quality improvement interventions to identified barriers: a multiple case analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;

13:161168.

14 Garland AF, Kruse M, Aarons GA. Clinicians and outcome measurement: whats

the use? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2003;

30:393 405.

15 Grol R, Grimshaw JM. From best evidence

to best practice: effective implementation

of change in patients care. Lancet. 2003;

362:12251230.

16 Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change:

barriers to and incentives for achieving

evidence-based practice. Med J Aust.

2004;180(6 suppl):S57S60.

17 Haines A, Kuruvilla S, Borchert M. Bridging the implementation gap between

knowledge and action for health. Bull

World Health Organ. 2004;82:724 731;

discussion 732.

18 Shaw B, Cheater F, Baker R, et al. Tailored

interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional

practice and health care outcomes.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:

CD005470.

19 Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Koke AJ. Responsiveness of functional status in low

back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain. 1996;65:7176.

20 Stratford PW, Gill C, Westaway M, Binkley

JM. Assessing disability and change on individual patients: a report of a patientspecific measure. Physiother Can. 1995;

47:258 263.

21 Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, et al. Two-,

six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed).

1982;284:16071608.

22 Strauss ALC. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for

Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

June 2010

Implementation of Measurement Instruments

23 Geboers H, Mokkink H, van Montfort P,

et al. Continuous quality improvement in

small general medical practices: the attitudes of general practitioners and other

practice staff. Int J Qual Health Care.

2001;13:391397.

24 van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T,

et al. Multifaceted strategies may increase

implementation of physiotherapy clinical

guidelines: a systematic review. Aust J

Physiother. 2008;54:233241.

25 Bekkering GE, Engers AJ, Wensing M, et al.

Development of an implementation strategy

for physiotherapy guidelines on low back

pain. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49:208 214.

26 Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G,

et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation

strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:

iiiiv, 172.

27 Peters ML, Patijn J, Lame I. Pain assessment

in younger and older pain patients: psychometric properties and patient preference

of five commonly used measures of pain

intensity. Pain Med. 2007; 8:601 610.

28 Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of

three commonly used pain rating scales.

J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:798 804.

29 Metcalfe CL, Lewin R, Wisher S, et al. Barriers to implementing the evidence base in

four NHS therapies: dieticians, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech

and language therapists. Physiotherapy.

2001;87:433 441.

30 Pollock AS, Legg L, Langhorne P, Sellars C.

Barriers to achieving evidence-based

stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2000;

14:611 617.

31 Jette DU, Halbert J, Iverson C, et al. Use of

standardized outcome measures in physical therapist practice: perceptions and applications. Phys Ther. 2009;89:125135.

32 Copeland JM, Taylor WJ, Dean SG. Factors

influencing the use of outcome measures

for patients with low back pain: a survey

of New Zealand physical therapists. Phys

Ther. 2008;88:14921505.

Appendix.

Examples of Questions in the Self-Analysis Lista

Questions

Fully

Disagree

Disagree

Neither

Agree nor

Disagree

Agree

Fully

Agree

Section 1: questions about yourself

I am able to interpret the outcome of measurement

instruments in the right way

I think it is important to document patient data in

an objective way

I think that the use of measurement instruments

does not take too much of my time

The use of measurement instruments is a fixed part

of my methodical approach

Section 2: questions about policy in your practice

In my practice, enough measurement instruments

are available

My supervisor supports employees in using

measurement instruments

The colleagues in my practice use measurement

instruments

a

The complete list is available on request from the authors.

June 2010

Volume 90

Number 6

Physical Therapy f

961

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Action Plan in School LibraryDocument3 paginiAction Plan in School LibraryRosanno David93% (15)

- Education: Nur Atiqah Nabilah RazaliDocument1 paginăEducation: Nur Atiqah Nabilah RazaliAtiqah Nabilah RazaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- KN ClinicalGuidelines2Document2 paginiKN ClinicalGuidelines2Mhmd IrakyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of Patient Preference Studies in HTA Decision Making: A NICE PerspectiveDocument5 paginiUse of Patient Preference Studies in HTA Decision Making: A NICE Perspectiveaxel pqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outcome Assessment in Routine Clinical Practice inDocument21 paginiOutcome Assessment in Routine Clinical Practice inicuellarfloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medidas en FT ImporDocument10 paginiMedidas en FT Imporleidy tatiana clavijo canoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conjoint in HEALTH ResearchDocument17 paginiConjoint in HEALTH ResearchDiana Tan May KimÎncă nu există evaluări

- COSMINDocument9 paginiCOSMINTamires NunesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient-Reported Physical Activity Questionnaires A Systematic Review of Content and FormatDocument18 paginiPatient-Reported Physical Activity Questionnaires A Systematic Review of Content and FormatHanif FakhruddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Published Researches in The Year 2010Document16 paginiPublished Researches in The Year 2010hsrimediaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Which Tool GuideDocument10 paginiWhich Tool GuideVina EmpialesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient CenteredDocument12 paginiPatient CenteredNina NaguyevskayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Body Metric Measuring MachineDocument22 paginiSmart Body Metric Measuring MachineIshimwe Moise SeboÎncă nu există evaluări

- GeografoDocument19 paginiGeografoSzelca Frien ZuñigaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 556-Appropriateness of Clinical Decision Support - Final White Paper-Wei WuDocument15 pagini556-Appropriateness of Clinical Decision Support - Final White Paper-Wei Wuapi-398506399Încă nu există evaluări

- Review Literature Hand Hygiene ComplianceDocument5 paginiReview Literature Hand Hygiene Complianceixevojrif100% (1)

- Developing A Theory-Based Instrument To Assess The Impact of Continuing Professional Development Activities On Clinical Practice: A Study ProtocolDocument6 paginiDeveloping A Theory-Based Instrument To Assess The Impact of Continuing Professional Development Activities On Clinical Practice: A Study ProtocolSjktraub PahangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etoshow QuityDocument8 paginiEtoshow QuityAr JayÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Common Threads in ProgramDocument5 paginiThe Common Threads in Programdate6Încă nu există evaluări

- Fasilita RefDocument10 paginiFasilita RefsukrangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quality Improvement ModelsDocument64 paginiQuality Improvement ModelsShahin Patowary100% (2)

- Implications in Practice and Conclusions - EditedDocument11 paginiImplications in Practice and Conclusions - EditedAtanas WamukoyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work-Related Medical RehabilitDocument12 paginiWork-Related Medical RehabilitMonicawindyÎncă nu există evaluări

- HospitalDocument7 paginiHospitalBENNY WAHYUDIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utility of Evidence Based NursngDocument12 paginiUtility of Evidence Based NursngrovicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- An To Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (Proms) in PhysiotherapyDocument7 paginiAn To Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (Proms) in PhysiotherapyAline VidalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy FrameworksDocument61 paginiPolicy FrameworksaninnaninÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Slade CERTDocument30 pagini2016 Slade CERTdamicarbo_297070015Încă nu există evaluări

- Implementation Strategies and Outcomes For Occupational Therapy in Adult Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping ReviewDocument26 paginiImplementation Strategies and Outcomes For Occupational Therapy in Adult Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping ReviewNataliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short-And Long-Term Effects of A Quality Improvement Collaborative On Diabetes ManagementDocument10 paginiShort-And Long-Term Effects of A Quality Improvement Collaborative On Diabetes ManagementBhisma SyaputraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outcome Research Methodology: BY Sumaira Naz BSN, MPHDocument40 paginiOutcome Research Methodology: BY Sumaira Naz BSN, MPHFatima AnxariÎncă nu există evaluări

- JHD 11 jhd220549Document19 paginiJHD 11 jhd220549NataliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 7 - EBP 2012-2013Document1 paginăModule 7 - EBP 2012-2013EspilfoviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physical Therapy Tests in Stroke RehabilitationDocument22 paginiPhysical Therapy Tests in Stroke Rehabilitationmehdi.chlif4374Încă nu există evaluări

- Updated Integrated FrameworkDocument17 paginiUpdated Integrated FrameworkE. Jimmy Jimenez TordoyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying The Analytic Hierarchy Process in Healthcare Research: A Systematic Literature Review and Evaluation of ReportingDocument27 paginiApplying The Analytic Hierarchy Process in Healthcare Research: A Systematic Literature Review and Evaluation of Reportingnormand67Încă nu există evaluări

- 1 Pressure Ulcer Case StudyDocument6 pagini1 Pressure Ulcer Case StudyTony MutisyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Comparative Analysis of Six Audit Systems For Mental Health NursingDocument10 paginiA Comparative Analysis of Six Audit Systems For Mental Health NursingByArdieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical PracticeDocument10 paginiClinical PracticeLenny Ronalyn QuitorianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Article Postop Recovery ProfileDocument8 paginiResearch Article Postop Recovery ProfileNi'mahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Value Based Healthcare Initiatives in Practice A.5Document26 paginiValue Based Healthcare Initiatives in Practice A.5Mario Luna BracamontesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Influencing The Implementation of Clinical Guidelines ForDocument11 paginiFactors Influencing The Implementation of Clinical Guidelines ForFhiserra RharaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Treatment Schedule of Conventional Physical Therapy Provided To Enhance Upper Limb Sensorimotor Recovery After Stroke Expert Criterion Validity and Intra-Rater ReliabilityDocument10 paginiA Treatment Schedule of Conventional Physical Therapy Provided To Enhance Upper Limb Sensorimotor Recovery After Stroke Expert Criterion Validity and Intra-Rater ReliabilityGeraldo MoraesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical Guide To Using Service User Feedback Outcome ToolsDocument99 paginiA Practical Guide To Using Service User Feedback Outcome ToolsPeter LawsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- MS-747 - Unit 23 - FORIDADocument24 paginiMS-747 - Unit 23 - FORIDANijam DulonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updated Integrated Framework For Making Clinical Decisions Across The Lifespan and Health ConditionsDocument13 paginiUpdated Integrated Framework For Making Clinical Decisions Across The Lifespan and Health ConditionsmaryelurdesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Practice Guideline For Physical Therapist Management of People With Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument16 paginiClinical Practice Guideline For Physical Therapist Management of People With Rheumatoid Arthritis1541920001 LUIS GUILLERMO PAJARO FRANCO ESTUDIANTE ACTIVO ESPECIALIDAD MEDICINA INTERNAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eip Gpe Eqc 2003 1Document24 paginiEip Gpe Eqc 2003 1rhuÎncă nu există evaluări

- IFOMPT Examination Cervical Spine Doc September 2012 DefinitiveDocument37 paginiIFOMPT Examination Cervical Spine Doc September 2012 DefinitiveMichel BakkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- SGPP Bestpracticescriteria en 0Document11 paginiSGPP Bestpracticescriteria en 0testÎncă nu există evaluări

- Omeract 3-799Document4 paginiOmeract 3-799damien333Încă nu există evaluări

- Healthcare Analytics 012Document9 paginiHealthcare Analytics 012bennettsabastin186Încă nu există evaluări

- tmp7BD7 TMPDocument25 paginitmp7BD7 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rounsaville. A Stage of Behavioral Therapies ResearchDocument10 paginiRounsaville. A Stage of Behavioral Therapies ResearchRubí Corona TápiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Article 1371Document10 pagini2016 Article 1371boyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to Clinical Effectiveness and Audit in HealthcareDe la EverandIntroduction to Clinical Effectiveness and Audit in HealthcareÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5com. Med - Mang.modified11Document22 pagini5com. Med - Mang.modified11Saad MotawéaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 Model and Process For Nutrition and Dietetic Practice 1Document20 pagini2020 Model and Process For Nutrition and Dietetic Practice 1Saba TanveerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Implementation of A Multidisciplinary Guideline For Low Back Pain Process Evaluation Among Health Care ProfessionalsDocument12 paginiImplementation of A Multidisciplinary Guideline For Low Back Pain Process Evaluation Among Health Care Professionalscallisto69Încă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Care PathwayDocument3 paginiIntegrated Care PathwayFitri EmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghid de OsteoporozaDocument55 paginiGhid de OsteoporozaMarius Creanga100% (1)

- 9.50 - 10.35 Mark Laslett Patho-Anatomic SourcesDocument78 pagini9.50 - 10.35 Mark Laslett Patho-Anatomic SourcesNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unraveling The Challenge of Head and Face Pain: EditorialDocument1 paginăUnraveling The Challenge of Head and Face Pain: EditorialNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- PolarityDocument13 paginiPolarityNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physical Exercise Intervention in Depressive Disorders: Meta-Analysis and Systematic ReviewDocument14 paginiPhysical Exercise Intervention in Depressive Disorders: Meta-Analysis and Systematic ReviewNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unstable Surface Improves Quadriceps:Hamstring Co-Contraction For Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention StrategiesDocument6 paginiUnstable Surface Improves Quadriceps:Hamstring Co-Contraction For Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention StrategiesNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Booklet LLLT July2014Document36 paginiResearch Booklet LLLT July2014NelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Randomized Clinical Trial of The Effectiveness of Mechanical Traction For Sub-Groups of Patients With Low Back Pain: Study Methods and RationaleDocument10 paginiA Randomized Clinical Trial of The Effectiveness of Mechanical Traction For Sub-Groups of Patients With Low Back Pain: Study Methods and RationaleNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yoga and Distractibility: Lee N. Burkett, PH.D., Megan A. Todd, M.S., Troy Adams, PH.DDocument11 paginiYoga and Distractibility: Lee N. Burkett, PH.D., Megan A. Todd, M.S., Troy Adams, PH.DNelsonRodríguezDeLeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activity Design For SSG Election 2021Document3 paginiActivity Design For SSG Election 2021ROZEL MALIFICIADO100% (2)

- Parent Presentation-Spring Registration Resources 9-11 2 22Document29 paginiParent Presentation-Spring Registration Resources 9-11 2 22api-548723359Încă nu există evaluări

- Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT)Document17 paginiTask-Based Language Teaching (TBLT)AlexanderBarreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan-MicroteachingDocument2 paginiLesson Plan-MicroteachingSella RanatasiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Pronunciation Without Using Imitation: Why and How - Messum (2012)Document7 paginiTeaching Pronunciation Without Using Imitation: Why and How - Messum (2012)Pronunciation ScienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sean M. SullivanDocument1 paginăSean M. Sullivanapi-309930792Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1 TPDocument2 paginiLesson 1 TPapi-228848608Încă nu există evaluări

- DLL Math Grade10 Quarter3 Week10 (Palawan Division)Document8 paginiDLL Math Grade10 Quarter3 Week10 (Palawan Division)MICHAEL MAHINAYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regional Safeguarding Standards During Online Interaction With Learners 1Document85 paginiRegional Safeguarding Standards During Online Interaction With Learners 1Tanglaw Laya May PagasaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of LLDocument55 paginiTheories of LLMoe ElÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOCSTUD 102 (World Hist & Civ 1)Document17 paginiSOCSTUD 102 (World Hist & Civ 1)Frederick W GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Susan Pinker Review ArticleDocument2 paginiSusan Pinker Review ArticleMuhammad Ali NasirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dividing Fractions Performance TaskDocument9 paginiDividing Fractions Performance TaskRyan McLeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cbar 2Document14 paginiCbar 2Chessa Mae PelongcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRF (MT) - Surname, First Name - Sy2022-2023Document2 paginiMRF (MT) - Surname, First Name - Sy2022-2023Romeo PilongoÎncă nu există evaluări

- LeannacrewsresumestcDocument3 paginiLeannacrewsresumestcapi-250337748Încă nu există evaluări

- Grammar Lesson Plan, English. Year4Document1 paginăGrammar Lesson Plan, English. Year4Kasthuri Bai ThangarajahÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPARW1Document2 paginiCPARW1Glenda ValerosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Certification Manual 5 20180511Document51 paginiCertification Manual 5 20180511Grupo Musical EuforiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- I. Objectives: Daily Lesson Log School: Grade Level: Teacher: Learning Area: Teaching Date: Quarter: Teaching TimeDocument5 paginiI. Objectives: Daily Lesson Log School: Grade Level: Teacher: Learning Area: Teaching Date: Quarter: Teaching TimeMelanie BitangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of ExercisesDocument78 paginiEvaluation of Exercisestitoglasgow100% (1)

- Classification of Standardized Achievement Test TestsDocument6 paginiClassification of Standardized Achievement Test TestskamilbismaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes For Letter of ExplanationDocument4 paginiNotes For Letter of ExplanationHHÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL in Math Week 4, Q3Document4 paginiDLL in Math Week 4, Q3Leonard Plaza100% (3)

- Em 314Document32 paginiEm 314Aristotle GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- English As A Second Language GuidelinesDocument10 paginiEnglish As A Second Language GuidelinesNataliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection Paper in Multigrade SchoolDocument7 paginiReflection Paper in Multigrade SchoolEden Aniversario0% (1)

- Community Helpers LessonDocument4 paginiCommunity Helpers Lessonapi-302422167Încă nu există evaluări