Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Understanding seizures in diabetes

Încărcat de

sohailsuDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Understanding seizures in diabetes

Încărcat de

sohailsuDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Farishta and Shaik UJP 2015, 04 (01): Page 60-65

www.ujponline.com

Universal Journal of Pharmacy

Review Article

ISSN 2320-303X

Take Research to New Heights

UNDERSTANDING SEIZURES IN DIABETES

Farishta Faraz1*, Shaik Abdul Suhale2

1

Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Mediciti institute of Medical sciences, Hyderabad, India

2

Registrar, Internal Medicine, Mediciti institute of Medical sciences, Hyderabad, India

Received 06-12-2014; Revised 04-01-2015; Accepted 02-02-2015

ABSTRACT

In diabetic patients, abnormal blood glucose levels may be associated with exacerbation of focal seizures.

Hyperglycemia leads to hyperexcitability of the neurons that make up the central nervous system, including the brain.

With the brain's overexcited imbalance, hyperglycemic seizures can be triggered. Hypoglycemia reduces the activity of

neurons in the brain ,which in turn reduces the activity across synapses ,the microscopic spaces in between neurons

that propagate the brains activities and preserve bodily function, thus leading to a seizure. Impaired activity across

synapses may lead to seizures. In the clinical setting, hypoglycemic seizures occur most commonly in individuals with

poorly regulated type 1 diabetes mellitus, especially at times of altered insulin availability or function. In children, 75%

of hypoglycemic seizures occur at night, which is the most vulnerable period for hypoglycemia, since sleep blunts the

counter regulatory responses to hypoglycemia. In young children, there is concern that severe hypoglycemic events can

cause permanent neurologic sequelae. It is therefore critical to know how long hypoglycemia can be tolerated before a

severe hypoglycemic event (seizure or coma) occurs. Recording of blood glucose levels before, during, or after seizures

rarely occurs. Without this information, it is difficult to determine whether hypoglycemia was the cause of the seizure.

Focal seizures associated with nonketotic hyperosmolar hyperglycemia are refractory to anticonvulsant treatment and

respond best to insulin and rehydration. It is difficult to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship between

hypoglycemia and seizures in the diabetic population. In the future, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology

may aid in the diagnosis.

Keywords: Diabetes, Seizures, Hypoglycemia, Hyperglycemia, Neuron, Brain.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common metabolic

and endocrine disease, defined by World Health

Organization as a syndrome consisting of a group of

metabolic

entities

characterized

by

chronic

hyperglycemia as the result of inadequate insulin

resistance and/or resistance to its biological effect1. An

epileptic seizure (or fits) is defined as a transient

symptom of abnormal excessive or synchronous

neuronal activity in the brain2. About 4% of people will

have an unprovoked seizure by the age of 80 and

chance of experiencing a second seizure is between

38% and 40%3. Seizures are categorized into generalized

and focal (or partial) types, depending upon whether

they arise deep within thalamocortical circuits, or from

a specific site (or focus) within the brain, respectively.

*Corresponding author:

Dr. FARAZ FARISHTA,

Assistant professor,Department of Internal Medicine,

Mediciti institute of Medical sciences Hyderabad, India.

Etiology of Seizures can vary from high fevers, viral

infections of the brain, head injuries, drug reactions or

insulin shock. Mixed signals from brain cells cause

seizures which are similar to those caused by a head

injury or a high fever.

Health care providers and patients have become aware

of the relationship between insulin, seizures and

coma4. Seizures are a common complication of

endocrine disease, either as a result of general

biochemical and metabolic abnormalities, or as a

specific syndrome related to the primary disease

process5. Hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) or

hypoglycemia (low blood glucose <3.9 mmol/L) can

cause seizures, which could lead to coma, convulsion,

or death if untreated6.

It is critical to know how long hypoglycemia can be

tolerated before a severe hypoglycemic event (seizure

or coma) occurs7. There is a paucity of data to support

whether it is absolute serum levels of glucose or rather

rapid changes that are more important for

epileptogenesis. Anticonvulsants used at doses that

control seizures in other disorders, often seem

Universal Journal of Pharmacy, 04(01), Jan-Feb 2015

60

Farishta and Shaik UJP 2015, 04 (01): Page 60-65

ineffective in treating seizures resulting from hypo- or

hyperglycemia5.

Clinical studies in diabetic patients have yielded varied

results, episodes of severe hypoglycemia have been

shown to alter brain structure and are reported to

cause significant cognitive damage in many, but not all

studies.8 Medical literature on the prevalence of

diabetes along with seizures is scarce. This article will

explore the features of seizures in diabetes mellitus,

including their incidence, prevalence, potential

underlying mechanisms that lead to seizures among

diabetic patient, treatment, and clinical evidence

available for this association.

Prevalence of seizures in diabetes mellitus

Hypoglycemia is the most prevalent clinical

complication in diabetic patients on insulin treatment

and continues to be the limiting factor in the glycemic

management of diabetes. Since severe hypoglycemia

affects 40% of insulin-treated people with diabetes,

concern regarding the hazardous potential for severe

hypoglycemia to cause brain damage continues to be

a very real barrier in striving to fully realize the

benefits associated with intensive glycemic control8.

Seizures have been reported to occur in 7-20% of all

diabetic patients. In the clinical setting, hypoglycemic

seizures occur most commonly in individuals with

poorly regulated type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM),

especially at times of altered insulin availability or

function. Hypoglycemic seizures also occur frequently

in infants of diabetic mothers and in newborns with

asphyxia, sepsis, congenital heart disease, and a

variety of hereditary metabolic disorders and

endocrinopathies9.

In children, 75% of hypoglycemic seizures occur at

night. Among patients with T1DM, there is a 6% lifetime

risk of dead-in-bed, which may in part be a result of

severe nocturnal hypoglycemia.7 In young children,

there is also concern that severe hypoglycemic events

can cause permanent neurologic sequelae.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial reported

the frequency of hypoglycemic loss of consciousness

events in patients with T1DM. In the studys intensive

therapy group, loss of consciousness events occurred at

a rate of 16.3 episodes per 100 patient-years, which

falls within the range of other reports4.

A study conducted by Ramakrishnan and Appleton

(2010) in the Paediatric Diabetes Clinic at Alder Hey

Childrens Hospital, UK, evaluated the prevalence of

epilepsy in 285 T1DM children below 16 years of age.

The prevalence of epilepsy in diabetic children was

found to be 21/100 (6 out of 285 children had

epilepsy), which was 6 times greater than the

prevalence in the general population of children in the

UK10.

Schober et al (2011)11 estimated the prevalence of

epilepsy and possible risk factors in children and

adolescents with DM. They conducted an observational

www.ujponline.com

cohort study, based on the Diabetes Patienten

Verlaufsdokumentation (DPV) database, including data

from 45,851 patients (52% male) with T1DM, aged

between 13.9 4.3 years (mean SD) and duration of

diabetes mellitus 5.4 4.2 years. The database was

searched for the concomitant diagnosis of epilepsy or

epileptic convulsions and for antiepileptic medication.

A total of 705 patients with epilepsy were identified,

giving a prevalence of 15.5 of 1000. Patients with

epilepsy were younger at onset of DM and shorter than

patients without epilepsy, and their weight and body

mass index were comparable. No difference could be

demonstrated for metabolic control, type of insulin

treatment, insulin dose, and prevalence of B-cell

specific autoantibodies. The frequency of severe

hypoglycemia was lower in patients treated with

antiepileptic medication. The risk for diabetic

ketoacidosis (DKA) was almost double in patients with

epilepsy compared with patients with T1DM alone

(P < 0.01). Children and adolescents with diabetes

mellitus show an increased prevalence of epileptic

seizures. For unknown reasons, there is an association

between epilepsy and diabetic ketoacidosis in children

with T1DM11.

Causes for diabetic seizures

In diabetic patients increase or decrease in blood sugar

levels can be attributed of different reasons, and these

fluctuations in blood sugar levels are primary cause of

seizures in these patients. With majority of episodes

occurring at night when the blood sugar levels are low.

Hypoglycemia can also be the result of pancreatic islet

cell dysfunction such as islet cell hyperplasia or

insulinoma. In such cases the seizures present during

the night or early morning are resistant to conventional

antiepileptic treatment5.

The long-term regulation of cerebral energy substrates

undoubtedly involves glycogen storage and release,

during acute seizures resulting from hypoglycemia, the

brains energy needs might be unmet, leading to the

adverse consequences for seizure susceptibility and

cognition9.

Glucose transport across the blood brain barrier is

reduced during seizures and therefore, it is assumed

that tissue hypermetabolism during the ictus is

independent of the plasma glucose level. It is unclear if

this presumed energy substrate deficiency may prolong

the seizures5.

Pathophysiology of hypoglycemic seizures

Glucose is known to play a critical role in brain

functions because it represents the main source of

metabolic energy generation. Hypoglycemic episodes,

particularly at night, are known to be a common

problem in patients with insulin-treated diabetes12.

Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) is the enzyme that

catalyzes the conversion of glutamic acid into -aminobutyric acid (GABA),

one of the classical

neurotransmitters with neuroinhibitory function. GAD is

Universal Journal of Pharmacy, 04(01), Jan-Feb 2015

61

Farishta and Shaik UJP 2015, 04 (01): Page 60-65

present only in GABAnergic neurons, but also in

pancreatic -cells, testis, liver, kidney, and adrenal

glands. AntiGAD antibodies are now considered to be a

marker of T1DM, since they can be found in the sera of

the majority of individuals with preclinical and early

phase T1DM13.

The mechanisms underlying the epileptic phenomena

during hypoglycemia have not yet been fully

understood, however, experimental studies suggest

that the loss of high-energy substrates for the

tricarboxylic acid cycle may cause a neurotransmitter

imbalance that result in a massive release of excitatory

amino acids and possible subsequent excitotoxic

effects. Consequently, hypoglycemia may, on the one

hand, induce epileptic symptomatic seizures and, on

the other, predispose to the development of

epileptogenic processes12.

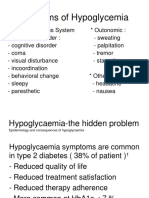

Symptoms of diabetic seizures

Seizures are the most common presenting neurological

symptoms of hypoglycemia at any age. Hypoglycemic

seizures usually occur at a serum glucose level of less

than 40 mg/dL.

The symptoms of diabetic seizures are similar to the

symptoms of epileptic or other types of seizures.6

Symptoms could be as faint as staring into space or

blinking, or as strong as violent convulsions6. Seizures

can range from mild to severe. Mild seizures may take

place and end in a matter of seconds. Severe seizures

may involve uncontrollable muscle spasms, rigidity, loss

of consciousness, loss of bladder and bowel control,

and in some cases, breathing that stops temporarily.6

A diabetic person experiencing seizures may have any

of the following symptoms5,6: muscles may twitch, jerk,

or slowly become rigid (clonic seizures); can, but do

not always causes violent convulsions; loss of muscle

tone (tonic seizures); can affect involuntary body

movement and function (clonic seizures); alter

sensation, awareness or behaviour; body parts can

become numb; tachycardia, palpitations, nervousness,

dizziness;

nausea;

sweating;

fatigue;

hunger,

headache; tremor, and brief loss of memory. These

symptoms may be followed by a change in mental

status, focal neurological signs, seizures, and coma5. A

diabetic person experiencing grand mal seizures could

call out, pass out, fall down, and injure themselves6.

Clinical evidence

Although there have been some reports of the

frequency of insulin-induced unconsciousness events,

validating the formal relationship in a clinical setting

may be difficult for several reasons4.Insulin induced

unconsciousness sometimes

can mimic a seizure

activity.

The association between T1DM and epilepsy is unclear

and requires more definitive epidemiologic analysis,

despite the fact that antibodies to glutamic acid

decarboxylase may provide a link between the two

conditions14.

www.ujponline.com

Hypoglycemia-induced Seizures

Hypoglycemia, common in diabetic patients treated

with insulin, can induce various neurological

disturbances. Of these, seizures are the most common

acute symptom, mainly of the generalized tonic-clonic

type, with focal events only exceptionally being

reported and documented. The relationship between

hypoglycemia and epileptic phenomena is complex and

has not yet been fully understood. Hypoglycemia can

modify cortical excitability by determining an

imbalance between excitation and inhibition; some

brain structures, such as the temporal lobe and

hippocampus, appear to be particularly susceptible to

this insult12.

Seizure caused by hypoglycemia is a benign and curable

situation, but it may be fatal if unrecognized.15 CNS

complications of diabetes mellitus increase with the

severity and chronicity of disease. Most seizures result

from severe metabolic abnormalities associated with

Nonketotic Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemia (NHH), DKA,

hyperglycemia, or from increase in cerebrovascular

disease from diabetes16.

Hypoglycemia can occur at anytime during the night,

most typically around 3 am. Undetected night time

hypoglycemia can lead to seizures and convulsions but

it is important to remember that not all seizures result

in convulsions. Two indications that a person has had a

severe night time episode of hypoglycemia (whether or

not seizures were involved) include waking with a high

fasting blood glucose level (Somogyi, or Rebound

Effect) and morning headache, and being drenched in

sweat.

Hart and Frier (1998)17 retrospectively analyzed the

clinical features of patients with acute hypoglycemia

admitted to the hospital with hypoglycemia in a large

teaching institution in a 12-month period. Of 51

patients, 41 had diabetes mellitus and the other had

hypoglycemia.

Neurological

manifestations

of

hypoglycemia were the main reason for hospital

admission, and 11 events (20%) had precipitant

convulsions. Patients who require hospital admission

for treatment of hypoglycemia have a high incidence of

neurological manifestations, a high rate of mental

illness and other medical disorders, and may represent

a high-risk subgroup with a poor long-term prognosis.17

Recently, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)

technology has allowed researchers to capture data

furthering the understanding of hypoglycemia-induced

seizures. The capturing of these seizure events on CGM

suggests that several factors, including nocturnal

timing, sleep status, and preceding duration of

hypoglycemia, may be necessary to create the clinical

event of a hypoglycemic seizure4.

Hyperglycemia-induced Seizures

The importance of glucose balance has been identified

in

studies

demonstrating

that

hyperglycemia

exacerbates ischemia-induced brain damage9.

Universal Journal of Pharmacy, 04(01), Jan-Feb 2015

62

Farishta and Shaik UJP 2015, 04 (01): Page 60-65

It is common practice to measure blood sugar content

in patients with acute episodes of convulsions.

However, very few reports deal with blood glucose

levels during fits in infancy. One study found raised

values (from 117 to 296 mg/100 mL) in 6 out of 12

children examined during or immediately after a febrile

convulsion. It appears that the hyperglycemia during a

convulsive episode is due to stress, is of short duration,

and probably has no pathological significance. It may

be important to bear in mind because of its possible

effects on the glucose level of the cerebrospinal fluid18.

Epileptic seizures or insulinoma in diabetes

Insulinoma, a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm deriving

mainly from pancreatic islet cells can secrete insulin in

short bursts and cause fluctuation of blood glucose

level correspondingly, and then the patients will have

intermittent neuroglycopenic symptoms, such as

conscious disorder, abnormal behavior, psychiatric

symptoms, or convulsion. Therefore, it is sometimes

misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures. Hypoglycemia can

activate focal abnormality in electroencephalography

(EEG) in epileptic who have an old lesion in the cortex.

The EEG for hypoglycemia usually shows diffuse or focal

slowing and enhanced response to hyperventilation.

However, the EEG in some patients with insulinoma

showed focal slowing (over the left mesial temporal

lobe) and later generalized spikes and sharp waves as

well as slow waves. An EEG slowing caused by

hypoglycemia represents an inhibitory state and

adaptive hypometabolism of the brain; additionally,

epileptiform discharges could reflect disarrangement of

neuronal excitation and inhibition as a result of

selective neuronal vulnerability to neuroglycopenic

damage. Various experimental studies confirmed that

severe hypoglycemia is able to induce spontaneous

synchronic discharges in vitro and in vivo, thus even

generate a hypermetabolic state and further deplete

the brain energy reserve. This seizure-like event cannot

be blocked by the common antiepileptic drugs15.

Diabetic ketoacidosis and epileptic seizures

Diabetic ketoacidosis, an acute complication of

diabetes mellitus, is characterized by the triad of

hyperglycemia, ketosis, and metabolic acidosis. DKA is

an emergency situation, can complicate mainly T1DM,

and hospitalization of the patient is necessary for

immediate treatment19. The American Diabetes

Association estimates that 5-25% of children with newly

diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus have DKA20.

There is a lower incidence of seizures in ketotic

hyperglycemia compared with NHH. Ketosis itself has

an anticonvulsant action due to intracellular acidosis

which is known to increase GAD activity leading to

enhanced GABA synthesis5,21. Ketogenic diets in

patients with intractable epilepsy are thought to be

effective through a similar mechanism5.

In the presence of hyperglycemia, GABA metabolism is

increased and the levels of this important inhibitory

www.ujponline.com

neurotransmitter may be depressed resulting in a

reduction of seizure threshold. Focal reduction in blood

flow may be important and is known to occur in

hyperglycemia but even when this was severe enough

to cause cerebral infarction focal seizures occurred

only when blood glucose was high21.

Nonketotic hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and focal

seizures

Nonketotic Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemia is one of the

most serious acute complications of diabetes, with

significant morbidity and mortality. It is characterized

by usually extreme hyperglycemia (> 600 mg/dL

[33.3 mmol/L),

hyperosmolality,

and

profound

dehydration, without significant ketoacidosis.

Focal seizures in adults may indicate diabetes mellitus.

Recurrent focal motor seizure was the first

manifestation of NHH of diabetes mellitus. The seizures

were characterized by stereotypical tonic changes in

body posture and arrest of speech that have been

associated with supplementary motor area seizures22.

In NHH, seizures occur early in hyperglycemia, when

the osmolality is only modestly increased, with minimal

reduction in sodium levels, and usually when

consciousness is preserved5. In general, 6% of the NHH

cases present with focal motor seizures, and 25% of

NHH patients eventually develop seizures5. Seizures

related to NHH may occasionally have strange features:

reflex seizures, speech arrest or have a visual

component, or transient subcortical T2 and fluid

attenuated inversion recovery hypointensity due to the

accumulation of free radical and iron deposition.

Focal seizures associated with NHH are refractory to

anticonvulsant treatment and respond best to insulin

and rehydration. The occurrence of focal seizures in a

middle aged to elderly patient should signal the

possibility of diabetes mellitus22.

Recognition of the link between this unusual form of

focal epilepsy and NHH would help in the early

diagnosis and treatment of the serious underlying

metabolic disturbance22.

Correlation between epileptic seizures and diabetes

mellitus during and after stroke

Epilepsy can occur as the first symptom of stroke

(associated seizure) during the acute stroke phase

(early epileptic seizure) within 2 weeks of the stroke

onset or as a consequence of stroke after 14 days or

later (late epileptic seizures). A retrospective study

conducted by Aljbegovi (2002)1 evaluated the impact

of diabetes on the onset of stroke and of the early/late

epileptic seizures in 7001 stroke patients. Of 114

patients with epileptic seizures, 34 (29.8%) had

diabetes mellitus (7.9% type 1 and 20.2% type 2): 19

with early seizures (3 with type 1 and 12 with type 2)

and 15 with late seizures (3 with type 1 and 11 with

type 2). The mean duration of diabetes after stroke in

patients with late and early seizures was 10 years and

14.7 years,

respectively.

Hyperglycemia

was

Universal Journal of Pharmacy, 04(01), Jan-Feb 2015

63

Farishta and Shaik UJP 2015, 04 (01): Page 60-65

significantly more common in the group of patients

with early seizures than in the group with late seizures

(60.9%). Diabetes mellitus was found to be a significant

risk factor for the onset of stroke as well as for the

occurrence of early epileptic seizures during stroke

(P< 0.1). In diabetics with stroke, hyperglycemia is a

significant factor that can lead to the occurrence of

early epileptic seizures1.

Relevance of electroencephalography in diabetic

seizures

The EEG is more responsive to acute hypoglycemia than

hyperglycemia. Generalized seizures with high voltage

spike activity, as well as focal discharges, can be seen

in metabolic disorders causing acute hypoglycemia,

such as insulinomas23. In severe hyperglycemia,

pronounced slowing is typical although focal

abnormalities can be seen. Exaggerated response to

hyperventilation and accentuation of underlying

interictal patterns can be seen during hypoglycemia.

The EEG changes in hypoglycemia are nonspecific. A

study performed by Bjrgaas and colleagues (1998)24

recorded quantitative EEG in 19 diabetic children

(mean age 14.2 [SD 1.4] years, mean HbA1c 9.8 [SD

1.2]%) and 17 nondiabetic children (mean age 14.3

[SD 1.1] years) exposed to a gradual reduction in serum

glucose. At specific serum glucose level of 4 mmoL,

diabetic children displayed significantly more EEG

deterioration during hypoglycemia than nondiabetic

children. This suggests that seizure thresholds may be

lower in diabetic patients, and factors other than

absolute serum glucose levels are responsible for the

seizures24.

Seizure management in diabetes mellitus

Hypoglycemia should be in the differential diagnosis of

any individual with seizures. Because diabetes is a

condition that typically uses hypoglycemia-causing

agents (insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents in the

sulfonylurea and meglitinide drug classes), it is

important to be aware that seizures in this population

could be iatrogenic4.

In seizing patients, particularly those taking insulin,

sulfonylureas, or meglitinides, hypoglycemia-induced

seizure should be considered. If clinically appropriate,

a seizing patient should be administered glucose as a

possible remedy4.

To prevent serious events such as seizures, glucose

sensors must both detect hypoglycemia and provide a

sufficiently robust alarm to awaken the patient or some

other member of the household7. It is difficult to

establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship between

hypoglycemia and seizures in the diabetic population.

In the future, CGM technology may aid in the

diagnosis4. If a person shows any of the symptoms of

diabetic seizure, then immediately seek medical help.

In case of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), honey or

syrup can be placed inside the gums or glucose

injection can be given to raise blood sugar levels. In

www.ujponline.com

case of hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), insulin

injections can be given to lower blood sugar levels.6

A diabetic person having a seizure can fall, bang their

bodies against objects or bite their tongues. Acute

seizures should be controlled, seizure prophylaxis with

antiepileptics should be instituted, and any causative

factors, including biochemical/metabolic abnormalities

and the primary disease process, should be corrected.5

It is important to measure antiGAD antibodies in

cerebrospinal fluid in case of T1DM whenever

accompanied by neurological disorders, such as seizure,

ataxia, rigidity, or painful spasms.13 Prompt treatment

of hypoglycemic seizures may help avert those

complications,

possibly

in

conjunction

with

neuroprotective agents that work independently of

glycogen (eg, NMDA receptor antagonists, GABA

receptor agonists)9.

Patients and caregivers must know how to avoid

seizures and to recognize their signs so that proper

immediate assistance is provided.

CONCLUSION

The potential cognitive consequences of severe

hypoglycemia, including coma and seizure, are a key

concern for clinicians, patients, and families. Diabetes

increases the risk of seizures. The magnitude of this

problem will continue to expand as the prevalence of

diabetes increases worldwide, thus presenting

numerous challenges for the future. There needs to be

greater awareness of the association of NHH and focal

epilepsy. If not recognized the diagnosis of diabetes

mellitus may be missed and the patient subjected to

unnecessary

investigations

and

inappropriate

treatment. Seizures in chronic diabetic patients

with/out comorbid conditions such as stroke, seizures

or other metabolic problems and antiepileptic drugs

effect on diabetes in general illustrates the importance

of appropriate education of patients with diabetes and

the techniques to prevent hypoglycaemia and needs

further evaluation and research. Self-report of severe

hypoglycaemia is an important prognostic indicator that

should be included in the clinical assessment of each

patient with diabetes. There is also need to undertake

more studies to correlate the blood and cerebrospinal

fluid glucose levels in convulsive episodes.

REFERENCES

1. Aljbegovic A, Metelko Z, Aljbegovic S,

Kantardzic D, Bratic M, Suljic E, Hrnjica M, and

Resi H. Correlation between early and late

epileptic seizures and diabetes mellitus during

and after stroke. Diabetologia Croatica 2002;

31-3: 173-177.

2 Fishcer R, van Emde Boas w, Blume W, Elqer C,

Genton P, Lec P, Engel J. Epileptic seizures &

epilepsy: definitions proposed by the ILAE &

IBE. Epilepsia 2005; 46(4): 470.

Universal Journal of Pharmacy, 04(01), Jan-Feb 2015

64

Farishta and Shaik UJP 2015, 04 (01): Page 60-65

3

10

11

12

13

Elerman ST. Single unprovoked seizures-current

treat options. Neurology 2004; 6 (3)243-255.

doi 10-1007/s 11940-004-0016-5.

Brennan MR and Whitehouse FW. Case Study:

Seizures and Hypoglycemia. Clinical Diabetes

2012; 30 (1): 23-24.

Beaumont A and Vespa PM. Chapter 7 Seizures

in fulminant hepatic failure, multiorgan failure,

and endocrine crisis. From: Seizures in Critical

Care: A Guide to Diagnosis and Therapeutics:

Clinical Current Neurology. Second Edition.

Edited by Panayiotis Varelas. ISBN 978-1-60327531-6. DOI 10.1007/978-1-60327-532-3-7.

Whitehead C. Symptoms of a Diabetic Seizure.

Available at: http://www.ehow.com/about_

4740229 _ diabetic - seizure - symptoms. html.

Accessed on 03 March 2012.

Buckingham B, Wilson D, Lecher T, Hanas R,

Kaiserman K, and Cameron F. Duration of

Nocturnal Hypoglycemia Before Seizures.

Diabetes Care 2008; 31 (11):21102112.

Bree AJ, Puente EC, Daphna-Iken D, and Fisher

SJ. Diabetes increases brain damage caused by

severe hypoglycemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol

Metab

2009;

297:

E194E201.

doi:10.1152/ajpendo.91041.2008.

Stratsform CE. Not all sweetness and light: the

role of glycogen in hypoglycemic seizures.

Epilepsy Currents, 2008; 8 (4): 105107.

Ramakrishnan R and Appleton R. Study of

prevalence of epilepsy in children with type 1

diabetes mellitus. Seizure. 2012 Feb 18. [Epub

ahead of print]

Schober E, Otto KP, Dost A, Jorch N, Holl R;

German/Austrian DPV Initiative and the BMBF

Competence Network Diabetes. Association of

Epilepsy and Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in

Children and Adolescents: Is There an Increased

Risk for Diabetic Ketoacidosis? J Pediatr. 2011

Nov 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Lapenta L, Bonaventura CD, Fattouch J, Bonini

F, Petrucci S, Silvia Gagliardi, Casciato S, et al.

Focal epileptic seizure induced by transient

hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetes.

Epileptic Disord 2010; 12 (1): 84-7.

Yoshimoto TY, Doi M, Fukai N, Izumiyama H,

Wago T, Minami I, Uchimura I, and Hirata Y.

Type 1 Diabetes mellitus and Drug-resistant

Epilepsy: Presence of High Titer of AntiGlutamic Acid Decarboxylase Autoantibodies in

www.ujponline.com

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Serum and Cerebrospinal Fluid. A Case Report.

Internal Medicine November 2005; 44 (11):

1174-77.

Vincent A and Crino PB. Systemic and

neurologic autoimmune disorders associated

with seizures or epilepsy. Epilepsia May 2011;

52 (Supplement s3): 1217.

Wang S, Hu H, Wen S, Wang Z, Zhang B, and

Ding M. An insulinoma with clinical and

electroencephalographic features resembling

complex partial seizures. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B

2008; 9(6):496-499.

Jane Boggs. Seizures and organ failure From

Seizures: medial causes and management.

Edited by Normal Delanty. ISBN 0-89603-827-0.

Hart SP and Frier BM. Causes, management and

morbidity of acute hypoglycaemia in adults

requiring hospital admission. Q J Med 1998;

91:505510.

Spirer Z, Weisman J, Yurman S, and Bogair N.

Hyperglycaemia and convulsions in children.

Arch Dis Child October 1974; 49(10): 811813.

Tentolouris N. and Katsilambros N. Diabetic

ketoacidosis in adults. Chapter 1. From

Diabetic Emergencies: Diagnosis and Clinical

Management. First Edition. Edited by:

Katsilambros N, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Liatis S,

Makrilakis K, and Tentolouris N.

Freeby M and Ebner S. Ketoacidosis and

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State. From:

Diabetes and the Brain. Edited by Biessels and

Luchsinger. Page 159-182. ISBN 978-1-60327849-2.

Hennis A, Corbin D, and Fraser H. Focal

seizures and nonketotic hyperglycemia. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55: 195-197.

doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.195.

Venna N and Sabin TD. Tonic Focal Seizures in

Nonketotic Hyperglycemia of Diabetes Mellitus

Arch Neurol. 1981; 38 (8): 512-514.

Scarpino O, Mauro AM, Del Pesce M, Partial

seizures and insulinoma: a case report.

Electroencephalography Clin Neurophypriol

1985; 61: 90 (abstract):38.

Bjrgaas M, Sand T, Vik T, Jorde R.

Quantitative

EEG

during

controlled

hypoglycemia in diabetic and non diabetic

children Diabet Med 1998; 15(1): 30-37.

Source of support: Nil, Conflict of interest: None Declared

Universal Journal of Pharmacy, 04(01), Jan-Feb 2015

65

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Naplex Complete Study Outline A Topic-Wise Approach DiabetesDe la EverandNaplex Complete Study Outline A Topic-Wise Approach DiabetesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Issa Strength and Conditioning IntroductionDocument7 paginiIssa Strength and Conditioning IntroductionFilip Pavloski0% (1)

- Ultimate Soccer Fitness GuideDocument51 paginiUltimate Soccer Fitness GuideJerricJeevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Homeopathic Treatment of Ear Infections PDFDocument104 paginiThe Homeopathic Treatment of Ear Infections PDFdipgang7174Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Fruit Sugar PDFDocument2 paginiUnderstanding Fruit Sugar PDFBobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perform Pre Lay Lay Activities PDFDocument95 paginiPerform Pre Lay Lay Activities PDFChristopher EstreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metabolic Encephalopathies and Delirium: Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PHDDocument34 paginiMetabolic Encephalopathies and Delirium: Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PHDjorge_suoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach To The Hypoglycemic PatientDocument13 paginiApproach To The Hypoglycemic PatientFiorella Peña Mora100% (2)

- PLR - Me Niche Attack Weight LossDocument21 paginiPLR - Me Niche Attack Weight LossPieter du PlessisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dha McqsDocument32 paginiDha Mcqssohailsu50% (2)

- Colo Vada Plus Hand OutDocument2 paginiColo Vada Plus Hand OutAnurag SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Chronic Liver Disease PDFDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Chronic Liver Disease PDFsohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chevron Safety Bulletin 2008Document12 paginiChevron Safety Bulletin 2008somayajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Symptoms of HypoglycemiaDocument20 paginiSymptoms of Hypoglycemiakenny StefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outpatientassessmentand Managementofthediabeticfoot: John A. DipretaDocument21 paginiOutpatientassessmentand Managementofthediabeticfoot: John A. DipretaAnonymous kdBDppigEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 12: NeurologyDe la EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 12: NeurologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ayurveda Q&A - Detoxification Therapy Cures Fungal Infection - Sify HealthDocument12 paginiAyurveda Q&A - Detoxification Therapy Cures Fungal Infection - Sify Healthsanti_1976Încă nu există evaluări

- MCQ Review For Saudi Licensing Exam (SLE)Document0 paginiMCQ Review For Saudi Licensing Exam (SLE)Rakesh Kumar83% (6)

- Managing Diabetes Through Proper Treatment and MonitoringDocument10 paginiManaging Diabetes Through Proper Treatment and Monitoringjoeln_9Încă nu există evaluări

- New Collect1Document5 paginiNew Collect1sohailsu100% (1)

- 1Document5 pagini1sohailsu100% (1)

- Ok sa Deped Program Accomplishment ReportDocument6 paginiOk sa Deped Program Accomplishment Reportkristine arnaizÎncă nu există evaluări

- HipoglikemiaDocument7 paginiHipoglikemiakarisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Adults Without Diabetes Mellitus - Clinical Manifestations, Causes, and DiagnosisDocument25 paginiHypoglycemia in Adults Without Diabetes Mellitus - Clinical Manifestations, Causes, and Diagnosismayteveronica1000Încă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Critically Ill Children: J Diabetes Sci TechnolDocument21 paginiHypoglycemia in Critically Ill Children: J Diabetes Sci TechnolSuryadi Soekiman RazakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabeticneuropathypart1: Overview and Symmetric PhenotypesDocument21 paginiDiabeticneuropathypart1: Overview and Symmetric PhenotypesPrima Heptayana NainggolanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Title: HypoglycemiaDocument13 paginiTitle: Hypoglycemia025 MUHAMAD HAZIQ BIN AHMAD AZMANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycaemia Unawareness: JP Vignesh, V MohanDocument6 paginiHypoglycaemia Unawareness: JP Vignesh, V MohanFaizudin HafifiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congenital Hyperinsulinism Current Trends in Diagnosis and TheraphyDocument14 paginiCongenital Hyperinsulinism Current Trends in Diagnosis and TheraphyJaka KurniawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 22 MetabolicEncephalopathies FinalDocument19 pagini22 MetabolicEncephalopathies FinalShravan BimanapalliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Hipoglikemik NeonatusDocument25 paginiJurnal Hipoglikemik NeonatusJosephine Ria PitasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypo Glice MiaDocument14 paginiHypo Glice MiaCarlos SandovalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Management of Diabetes in The Elderly: Practical PointersDocument4 paginiClinical Management of Diabetes in The Elderly: Practical Pointersannaafia69969Încă nu există evaluări

- Stress Response in Critical Illness: Laura Santos, MDDocument9 paginiStress Response in Critical Illness: Laura Santos, MDPutri Wulan SukmawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study - Seizures and HypoglycemiaDocument2 paginiCase Study - Seizures and Hypoglycemiamob3Încă nu există evaluări

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument6 paginiNew Microsoft Word DocumentKawther El-FikyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hanhan 2001Document12 paginiHanhan 2001ATIKAH NUR HAFIZHAHÎncă nu există evaluări

- BackgroundDocument3 paginiBackgroundmnyur_red_leechÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hyperglycemic CrisisDocument9 paginiHyperglycemic CrisisRoberto López MataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Toddler With A Diaper RashDocument4 paginiDiabetic Ketoacidosis in Toddler With A Diaper RashKarl Angelo MontanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Patients With Insulin Treated Diabetes: Review ArticleDocument9 paginiHypoglycemia in Patients With Insulin Treated Diabetes: Review ArticleEmanuel BaltigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case 16 QuestionsDocument10 paginiCase 16 Questionsapi-532124328Încă nu există evaluări

- Key Concepts: Susan J. Rogers and Jose E. CavazosDocument24 paginiKey Concepts: Susan J. Rogers and Jose E. CavazosLia Ruby FariztaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijms 24 09357 v2Document14 paginiIjms 24 09357 v2MSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Approach To Hypoglycemia inDocument9 paginiClinical Presentation and Diagnostic Approach To Hypoglycemia inRichard Loor RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kejang Hiperglikemi PDFDocument10 paginiKejang Hiperglikemi PDFNishfullaili Nurun NisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grp.10 DiabetesDocument15 paginiGrp.10 DiabetesVanessa JanneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endocrine Alterations in Critical IllnessDocument56 paginiEndocrine Alterations in Critical IllnessyaminmuhÎncă nu există evaluări

- HypoglicemiaDocument4 paginiHypoglicemiayeniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia 2Document14 paginiHypoglycemia 2ghostmanzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia - 2014 Morales N DoronDocument8 paginiHypoglycemia - 2014 Morales N DoronDian Eka RamadhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Critically Ill ChildrenDocument10 paginiHypoglycemia in Critically Ill ChildrenCiendy ShintyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Link Between Seizures and Type 1 Diabetes ExploredDocument10 paginiLink Between Seizures and Type 1 Diabetes ExploredAbigail PheiliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Diabetes: P E. C, S N. D, H SDocument11 paginiHypoglycemia in Diabetes: P E. C, S N. D, H SFabio FabbriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wernicke Encephalopathy: EtiologyDocument6 paginiWernicke Encephalopathy: EtiologyDrhikmatullah SheraniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Hipoglikemia 1Document11 paginiJurnal Hipoglikemia 1dimas gilang prakosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach To Hypoglycemia in Infants and Children - UpToDateDocument31 paginiApproach To Hypoglycemia in Infants and Children - UpToDateyohanes gabriel dwirianto w.aÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2Document5 paginiLiterature Review of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2c5td1cmc100% (1)

- Addison Disease: Diagnosis and Initial ManagementDocument5 paginiAddison Disease: Diagnosis and Initial ManagementI Gede SubagiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CaseDocument7 paginiCaseDenny EmiliusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in DiabetesDocument12 paginiHypoglycemia in Diabetesnaili mumtazatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- DKADocument12 paginiDKAAisha SyedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hipoglicemiadm2 2004Document8 paginiHipoglicemiadm2 2004Victor Bazan AlvarezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice Essentials: Neonatal HypoglycemiaDocument15 paginiPractice Essentials: Neonatal HypoglycemianadiancupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Hypoglycemia in Neonates Leading To Brain Injury ThesisDocument3 paginiEffects of Hypoglycemia in Neonates Leading To Brain Injury ThesisPratibha AgrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pediatric Type 1 Diabetes MellitusDocument25 paginiPediatric Type 1 Diabetes MellitusmuhammadferhatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predictors of Poor Prognosis in Hypoglycemic EncephalopathyDocument5 paginiPredictors of Poor Prognosis in Hypoglycemic EncephalopathyJennifer JaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- NewbornEmergenices2006 PDFDocument16 paginiNewbornEmergenices2006 PDFRana SalemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hepatic encephalopathy in adults: Treatment (uptodate)Document35 paginiHepatic encephalopathy in adults: Treatment (uptodate)kabulkabulovich5Încă nu există evaluări

- Ketogenic Diet and EpilepsyDocument13 paginiKetogenic Diet and EpilepsyDra Jessica Johanna GabaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jcem 0709Document20 paginiJcem 0709Rao Rizwan ShakoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- HypoglicemicDocument20 paginiHypoglicemicAndreea CreangaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Claire P. SmithDocument6 paginiDiabetic Ketoacidosis: Claire P. SmithPaco OrtezÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Guide to Diabetes: Symptoms; Causes; Treatment; PreventionDe la EverandA Guide to Diabetes: Symptoms; Causes; Treatment; PreventionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionDe la EverandHypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Conversion DisorderDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Conversion DisordersohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Conversion DisorderDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Conversion DisordersohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES ChoreaDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES ChoreasohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Autonomic Neuropathy 2nd EditionDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Autonomic Neuropathy 2nd EditionsohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRCP Recalls May 2014Document15 paginiMRCP Recalls May 2014sohailsu100% (1)

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Autonomic Neuropathy 2nd EditionDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Autonomic Neuropathy 2nd EditionsohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Cervical MyelopathyDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Cervical MyelopathysohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bajaj Allianz receipt for Rs. 19,087Document1 paginăBajaj Allianz receipt for Rs. 19,087sohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Charcot Marie Tooth Disease 2nd EditionDocument2 paginiALSANGEDY BULLETS FOR PACES Charcot Marie Tooth Disease 2nd EditionsohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faq V2.2Document6 paginiFaq V2.2Rrichard Prieto MmallariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q.No. Key Q.No. Key Q.No. Key Q.No. Key: Key To P.G. Medical Entrance Test - 2012 Code - A DATE: 12-03-2012Document1 paginăQ.No. Key Q.No. Key Q.No. Key Q.No. Key: Key To P.G. Medical Entrance Test - 2012 Code - A DATE: 12-03-2012sohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- For Foreign Medical Officers Malaysian LicenseDocument2 paginiFor Foreign Medical Officers Malaysian LicensesohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cardiac Cycle Electrical Mechanical EventsDocument49 paginiCardiac Cycle Electrical Mechanical EventssohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common symptoms and conditions in obstetrics, gynecology, and primary careDocument5 paginiCommon symptoms and conditions in obstetrics, gynecology, and primary caresohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intro To Android and iOS: CS-328 Dick SteflikDocument15 paginiIntro To Android and iOS: CS-328 Dick StefliksohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 IndexDocument1 pagină2013 IndexsohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- TTT of FrostbiteDocument7 paginiTTT of FrostbitesohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6099 March2009Document7 pagini6099 March2009Mohanned TahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Collect3Document7 paginiNew Collect3Mohanned TahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sle Mar2010Document16 paginiSle Mar2010sohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- WD 0000011Document8 paginiWD 0000011sohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2010Document15 pagini2010sohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 IndexDocument1 pagină2013 IndexsohailsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mcqs in DentistryDocument135 paginiMcqs in Dentistrysohailsu50% (2)

- Pancretic Cancer Case Study - BurkeDocument52 paginiPancretic Cancer Case Study - Burkeapi-282999254Încă nu există evaluări

- UGEB2363-1718-week 5 To 6Document70 paginiUGEB2363-1718-week 5 To 6Gladys Gladys MakÎncă nu există evaluări

- GAIN Report ThailandDocument45 paginiGAIN Report ThailandWarrenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metals As Co-Enzymes and Their SignificanceDocument10 paginiMetals As Co-Enzymes and Their Significanceom prakash royÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemical Composition and Nutritional Value of Emmer Wheat (Triticum Dicoccon Schrank) : A ReviewDocument18 paginiChemical Composition and Nutritional Value of Emmer Wheat (Triticum Dicoccon Schrank) : A Reviewthor ragnarokÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Update Food Security MonitoringDocument13 paginiGlobal Update Food Security MonitoringNasrul SetiawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- IDA REGISTERED DIETITIAN EXAMINATIONDocument9 paginiIDA REGISTERED DIETITIAN EXAMINATIONVinodMoreMoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature ReviewDocument5 paginiLiterature Reviewapi-534395189Încă nu există evaluări

- SPM 4551 2006 Biology k2 BerjawapanDocument15 paginiSPM 4551 2006 Biology k2 Berjawapanpss smk selandarÎncă nu există evaluări

- B1-VSTEP Speaking Simulation TestsDocument5 paginiB1-VSTEP Speaking Simulation TestsHữu NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09 Prostate Cancer LRDocument154 pagini09 Prostate Cancer LRDiana Pardo ReyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 16Document19 pagini16phanisai100% (2)

- 150 FactsDocument13 pagini150 Factsapi-256471149Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Vitamins: With Dr. Georgina CornwallDocument11 paginiIntroduction To Vitamins: With Dr. Georgina CornwallimnasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coa Sas 1 23 CfuDocument50 paginiCoa Sas 1 23 Cfuella retizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Consumer Preference For Coconut Sugar Using Conjoint Analysis Approach 121212Document5 paginiUnderstanding Consumer Preference For Coconut Sugar Using Conjoint Analysis Approach 121212Ralph Justin IIÎncă nu există evaluări

- OpdDocument341 paginiOpdzahrabokerÎncă nu există evaluări

- CXS 256eDocument5 paginiCXS 256eFatima AucenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- OOD MICROBIOLOGY: THE BASICS OF CHEESE PRODUCTIONDocument5 paginiOOD MICROBIOLOGY: THE BASICS OF CHEESE PRODUCTIONGeorge MarkasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Berg Has Devised A Unique Ketogenic Diet That Is Adaptable To Any LifestyleDocument3 paginiDr. Berg Has Devised A Unique Ketogenic Diet That Is Adaptable To Any LifestylePR.comÎncă nu există evaluări