Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Mukundan, Et Al. (2013) - World Applied Sciences Journal 22

Încărcat de

Labirin MazeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Mukundan, Et Al. (2013) - World Applied Sciences Journal 22

Încărcat de

Labirin MazeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

World Applied Sciences Journal 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

ISSN 1818-4952

IDOSI Publications, 2013

DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.22.12.730

Malaysian Secondary School Students ESL

Writing Performance in an Intensive English Program

1

Jayakaran Mukundan, 1Elaheh Hamed Mahvelati, 2Mohd Amin Din and 3Vahid Nimehchisalem

Faculty of Educational Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia

2

Secondary Education Division, Mara, Malaysia

3

Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia

1

Abstract: The available literature regarding the effect of intensive programs on students English as a Second

Language (ESL) writing indicates inconsistencies that necessitate further research in the area. This paper

presents the results of one of the phases of an on-going school adoption project that aims at developing lowscoring learners general English proficiency. The present study focused on the learners English writing

performance before and after an intensive intervention program. A quantitative method with a single group

quasi-experimental design was followed to meet this objective. The findings indicated that the participants

writing skills improved in reference to five different domains of writing that included content, language use,

organization, vocabulary and mechanics. The results of paired samples t-tests also showed that the mean

differences between the pre- and post-test scores assigned for the participants written samples were

statistically significant (p<.05) for all the five domains. The findings and their pedagogical implications have

been discussed.

Key words: English as a Second Language writing

School students

INTRODUCTION

In October 2011, the UPM-MRSM School Adoption

Program was initiated by the Faculty of Educational

Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), a research

university in Malaysia. The focus was on students from

MRSM*, Maktab Rendah Sains Mara (in Malay), MARA

Junior Science College (in translation) in Kuala Krai

(Kelantan, Malaysia). Established in 1972, MRSM is a

group of boarding schools for bright Malaysian students.

As a part of this project, an intensive four-week English

program was provided by the ELS Language Centres,

Malaysia, for a group of Form 4 students. The program

was proposed with the primary objective of improving

low-scoring Malaysian school students general English

proficiency. The intensive English program, conducted at

ELS Language Centres, is called the Certified Intensive

English Program (CIEP), a full-time English language

proficiency course in 9 levels of 101 to 103 (Beginning),

104 to 106 (Intermediate) and 107 to 109 (Advanced).

Previous research indicated

the CIEP could

Intensive English program

Malaysian Secondary

significantly improve the English language proficiency of

a group of adult learners over a period of 6 months [1].

A more recent study also indicated the statistically

significant effect (p<.05) of the same intensive program on

the Form 4 students general English language proficiency

[2].

The present paper focuses on the effect of the

intensive program on the students writing performance.

Within the scope of the present study, writing

performance is evaluated by the student writers total

writing scores as well as their scores in each of the

sub-scales of the ESL Composition Profile [3]. These

sub-scales help raters assign scores for students writing

with respect to their:

Content: development of thesis and relevance to the

assigned topic,

Organization:

fluent

expression;

clearly

stated/supported, succinct, well-organized, logically

sequencing and cohesive presentation of ideas,

Vocabulary:

sophisticated

range,

effective

Corresponding Author: Dr. Vahid Nimehchisalem, Department of English Language,

Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, Universiti Malaya, 60603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Tel: +60-3 7967 3089, H/P: +60-17 667 8715.

1677

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

word/idiom choice and usage, word form mastery,

appropriate register,

Language use: effective complex constructions, few

errors of agreement, tense, number, word,

order/function, articles, pronouns and prepositions,

and

Mechanics: mastery of conventions, few errors of

spelling,

punctuation,

capitalization

and

paragraphing [3].

Objective and Research Questions: This study focused

on the effect of an intensive program on the students

writing performance. The following research questions

were addressed to meet the aforementioned objective:

Does the intensive program significantly affect the

students writing performance with respect to their

content scores?

Does the intensive program significantly affect the

students writing performance with respect to their

organization scores?

Does the intensive program significantly affect the

students writing performance with respect to their

vocabulary scores?

Does the intensive program significantly affect the

students writing performance with respect to their

language use scores?

Does the intensive program significantly affect the

students writing performance with respect to their

mechanics scores?

Literature Review: Second language (L2) writing has

always presented serious difficulties for language

learners. Hence, it has been widely studied and hotly

debated by various researchers and scholars since 1960s.

Traditionally, there was a widely-held view that writing

was nothing more than the written representation of

speech which only functioned as a tool for the practice

and learning of certain lexical and grammatical rules [4].

Indeed, writing was not seen as one of the goals of

language learning which was worth spending the time of

class since the dominant idea was that as far as language

learners had enough knowledge of grammar and spelling,

they would have the ability of writing.

However, this view has been challenged by many

researchers from various linguistic fields in the recent

decades. In fact, the prevalence of information

technology, learners practical needs and the

development in the various areas of English for Specific

Purposes have highlighted the significance of L2 writing

as a crucial skill which needs time and practice in

language learning settings [5, 6, 7]. Thus, finding viable

ways to improve L2 learners writing skill has become a

serious concern for L2 writing specialists [8, 9].

In some learning-teaching contexts where learners

face time constraints in learning the language skills,

intensive programs have emerged. The aim of these

courses is to facilitate students learning of ESL writing

skills in a shorter period. For example, in the case of the

present study, intensive teaching format was inevitable

due to the fact that the subjects were the low scoring

students who needed more practice to catch up with their

peers in Kuala Krai, while their school and ELS Language

Centres were located far apart from each other. Therefore,

time planning was an important determinant since they

could attend the English courses for only a short period

during their school holidays.

There has been debate about the efficacy of

intensive courses. Advocates of intensive courses assert

that accelerated teaching programs have a significant

effect on learners English knowledge development

[10-13]. The superiority of the outcome of intensive

English programs over regular courses has been

corroborated in the related literaturte [14]. Lightbown and

Spada (1989) conducted a study on the second language

development of francophone learners in an experimental

intensive English course in Quebec and their results

indicated that the program had an effective role in

improving the students productive and receptive skills

[14].

The findings of a study

by

Raymond

(1995, cited in 15) revealed that intensive English courses

could help learners develop competence in L2 writing. In

addition, Carson and Kuehn (1992) carried out a study on

a group of Chinese students attending academic and

pre-academic intensive English courses in the US [16].

The main focus of their study was on the possible

relationship between L1 and L2 writing development of

the learners in an L2 environment. However, the positive

results associated with L2 writing development of those

learners attending pre-academic intensive English

programs could be taken as the proof of the program

efficacy.

In the US, Paulus (1999) compared the effect of

teacher feedback with peer feedback in a study on 11 ESL

students attending an intensive writing course [17].

This course which was held four times a week for ten

weeks was regarded as an intensive English language

course by Jun (2008) in his review of L2 writing studies.

However, Paulus himself did not describe the course as

intensive or non-intensive. Pauluss study was conducted

on a group of learners who were attending an intensive

English course and the results indicated some positive

changes in the learners writing performance. The findings

1678

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

of his study also revealed that most of these significant

changes were effected by the teachers comments which

lent support to the claim of teacher intervention

proponents [17].

Contrary to the above-mentioned studies, a study

conducted by the Abestrie School Board reported mixed

results about the effectiveness of intensive English

courses (Gouvernement du Qubec, 1993, cited in 15).

More precisely, the L2 achievement of a group of learners

after having attended an intensive English course was

examined and the results indicated that the intensive

program could not improve the L2 writing competencies

of all the learners. In other words, the findings suggested

that only a group of learners could benefit from the

program and increase the level of their writing

performance. Similarly, although a study by

Jacques-Bilodea (2010) indicated positive effects of

intensive English courses, a deeper analysis of the results

revealed that the participants did not feel satisfied with

their writing competencies. They found writing to be one

of the most challenging skills in the intensive courses

which needed more time and practice [15].

As the review of this body of the related research

indicates, first, studies that investigate the effect of

intensive writing interventions are scarce and second, the

few available studies indicate little consistency in their

results. Hence, there is still a need for more research on

this issue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The objective of the present study was to investigate

the effect of an intensive English program on a group of

ESL students writing performance. To meet this objective

quantitative method was used. A single group quasiexperimental design was followed. This section presents

the participants, treatment, tasks, instrument, evaluators

and the data analysis method of the study.

Participants: The participants of the study were randomly

selected low-scoring students (n=30) in English Language

from Form 4, MRSM Kuala Krai, Kelantan, Malaysia. They

were 16 years of age and about 73% of them were males.

Treatment: The participants went through a four-week

intensive intervention program at ELS Language Centres,

Subang Jaya in December 2011. They took a placement

test and were assigned to 5 different levels (101-105; that

is, elementary to intermediate) based on their scores. In

ELS Language Centres, levels 101-103 are categorized as

basic while 104-106 are referred to as intermediate

levels. Only one student was assigned to level 101 and

one to level 105. A majority of the students (56.7%) were

placed in 103, a few (26.7%) in 102 while only 3 (10%) in

104. After the placement test, the participants went

through the intervention in their respective levels. The

intensive intervention was a full-time

program

(Mondays-Thursdays, 8.30-15.30; Fridays, 8.30-12.30)

and overall lasted 4 weeks (20 days). The participants in

each level took 28 lessons with a duration of 55 minutes

every week in all language skills, including, speaking,

listening, reading, writing, pronunciation, vocabulary and

grammar. The components that the participants went

through comprised (I) Structure and Speaking Practice

(2 periods daily, each period being 55 minutes), (ii)

Reading and Writing (2 periods daily), (iii) Conversation

(1 period daily) and (iv) E-Learning Language Technology

(1 period daily). The overall effect of the program has

been reported in a previous publication [2]. The present

paper focuses specifically on the Reading and Writing

componentof the intensive program.

The Reading and Writing component aimed at

improving learners reading and writing skills in an

integrative way. The focus was on learners reading

comprehension and reading speed while practicing skills

such as predicting content, skimming, scanning, drawing

inferences and conclusions, guessing meanings of new

vocabulary from context and summarizing information.

Then, they responded to the reading material through

group discussions and writing in English. Depending on

their level of proficiency, they were exposed to different

genres of writing ranging from basic descriptive essays at

the beginning levels to more advanced argumentative

essays at the higher levels. The reading materials included

the ELS U.S. Proprietary Materials that emphasize reading

comprehension and reading speed. They provide practice

for reading skills like scanning, skimming, predicting

content, drawing conclusions and inferences and

guessing meanings. Table 1 indicates the writing skills

that the participants covered at their respective levels:

Tasks and Instrument: The participants were asked to

write a 200-word story about a memorable trip/day (at

the pre-test) and about a terrible experience/day (at the

post-test). The topics were similar and both prompted a

narrative response.

The rating scale that was used to rate the samples

was a generic analytic scale, the ESL Composition Profile

[3]. The scale consists of five ESL writing sub-constructs

of writing, including, content, language use, organization,

vocabulary and mechanics. With a total score range of

34-100, the scale distinguishes four groups of student

writers, namely very poor, fair to poor, good to

average and excellent to very good. Each sub-scale of

1679

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

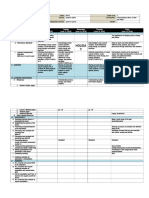

Table 1: Writing skills covered in the Reading and Writing component

Level

Writing skills

101

Description of self, family, friends and daily activities (Personal attributes/ Daily routines) Applying basic punctuation in writing; periods,

question marks and observing capitalization rules Writing a single paragraph with topic and concluding sentences

102

Writing instructions (Process/ Directional) Showing mastery of simple sentence structures Using common punctuation conventions Organizing

a single paragraph using correct form, indentation, basic sentence structure Organizing facts using rank and order into a paragraph

103

Writing a single paragraph descriptive narrative of people and lifestyles or describing an event Writing good topic sentences and supporting

sentences Using correct word order, punctuation and capitalization Editing for mistakes in spelling, punctuation, vocabulary or grammar

104

Writing a 3 paragraph Process Informational essay Writing effective thesis statements to introduce the process Writing good topic sentences and

supporting statements Demonstrate a good mastery of high frequency punctuation principles, capitalization and use of transition words Making

a summary or concluding statement

105

Writing a 4 to 5 paragraph Classification essay Writing effective thesis statements Applying appropriate classification principles Using vocabulary

appropriate to the level Using high frequency punctuation correctly Applying revising and editing skills

the instrument carries a different weight. Content is given

the highest weight (30% of the total score). Language use,

organization and vocabulary have been assigned

moderate weights (25%, 20% and 20% of the total mark,

respectively), while mechanics receives the lowest

(only 5% of the total mark). Based on the scale, the lowest

and highest scores that a rater could assign for different

dimensions of writing include 13 to 30 for content, 5 to 25

for language use, 7 to 20 for organization as well as

vocabulry and finally 2 to 5 for mechanics.

Raters: Two English Language Teaching (ELT) experts

holding PhD degrees in Teaching English as a Second

Language (TESL) with a minimum teaching experience of

10 years rated the samples. It is common practice to have

two raters evaluate the same samples and then have a

third rater evaluate the samples if the two raters fail to rate

consistently [18]. In order to measure the inter-rater

reliability the Pearson Product Moment Correlation was

employed. Inter-rater reliability tests indicated very

high reliability coefficients both for the pre-test

(r = .90) and the post-test (r = .93). Therefore, the samples

were not given to a third rater to be scored. The

average values of the two raters scores were used for

data analysis.

Data Analysis Method: In order to analyze the data SPSS

(Version 18) was used. Paired samples t-tests were used to

test the significance of the difference between the

students pre- and post-test scores. The significance level

was set at .05 for all the tests.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To answer the research question dealing with the

effectiveness of the intensive English program on the

subjects writing performance, their pre-test scores were

compared with their post-test scores (Table 2).

According to Table 2, the result of the within

group comparison indicated that the subjects post-test

(M = 77.21, SD = 4.10) scores were considerably higher

than their pre-test (M = 53.13, SD = 6.60) scores.

Additionally, the statistical significance of the mean

difference between the learners scores in the pre-test and

post-test was tested (Table 3).

As Table 3 demonstrates, the mean difference of

24.08 between the pre-test and post-test scores was

statistically significant, (29) = 15.98, p= .000. Hence, the

result proved that the intensive course could help the

learners improve their writing.

A deeper analysis on separate dimensions of the

subjects written works revealed that the intensive

program could have beneficial effects on all the

sub-constructs

of

writing,

including

content,

organization, vocabulary, language use and mechanics.

In other words, as Table 4 indicates, the subjects pre-test

scores for each sub-scale were significantly lower than

their post-test scores.

The mean differences between the pre-test and

post-test scores for each sub-scale of writing were

tested for their statistical significant using paired samples

t-tests. Table 5 summarizes the SPSS output for these

tests.

According to the table, the difference between

the pre-test and post-test scores for each sub-scale

[Content t(29)= 26.39, p= .000, Organization t(29)= 5.77,

p= .000, Vocabulary t(29)= 8.79, p= .000, Language

use t(29)= 13.49, p= .000 and Mechanics t(29)= 4.78,

p= .000<.05] was statistically significant. That is, all the

dimensions of the learners writing were positively

affected by the intensive teaching format provided at ELS

Language Centres.

The significant improvement observed in the writing

performance of the subjects of this study corroborates the

results of the previous studies which proved the

efficacy of intensive instructional formats [10,12,19,13].

1680

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for pre and post-test scores

N

Mean (upon 100)

SD

Pre-test

30

53.13

6.60

Post-test

30

77.21

4.10

Table 3: Paired samples t-test results

Mean

df

-24.08

-15.98

29

Sig (2-tailed)

Pair 1

Pretest-Posttest

.000*

* Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed)

Table 4: Descriptive statistics for pre and post-test scores (n=30)

Dimension

Test

Mean

SD

Content

Pre-test

20.10

1.91

(score upon 13-30)

Post-test

29.76

.62

Organization

Pre-test

11.73

2.33

(scores upon 7-20)

Post-test

14.36

.96

1.25

Vocabulary

Pre-test

10.53

(scores upon 7-20)

Post-test

13.60

1.22

Language use

Pre-test

7.46

2.19

(scores upon 5-25)

Post-test

15.20

2.36

Mechanics

Pre-test

3.26

.44

(scores upon 2-5)

Post-test

3.76

.56

Table 5: Paired samples t-test results

Mean

df

Sig (2-tailed)

-9.66

-26.39

29

.000*

-2.63

-5.77

29

.000*

-3.06

-8.79

29

.000*

-7.73

-13.49

29

.000*

-.50

-4.78

29

.000*

Pair 1 (Content)

Pretest-Posttest

Pair2 (Organization)

Pretest-Posttest

Pair 3 (Vocabulary)

Pretest-Posttest

Pair 4 (Language use)

Pretest-Posttest

Pair 5 (Mechanics)

Pretest-Posttest

* Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed)

Furthermore, these findings are consistent with Carson

and Kuehns study [16] which revealed that the language

learners writing abilities could be enhanced through

intensive courses. They conducted a study on 48 Chinese

students attending pre-academic intensive English

courses, universities and graduate schools in the U.S. to

explore the possible relationship between their L1 and L2

writing competence. Although Carson and Kuehn [16] did

not mention anything directly about the impact of the

intensive programs on their subjects L2 writing

development, their results can be regarded as proof of the

effectiveness of intensive courses on L2 learners writing

enhancement. In other words, the results associated

with the performance of those subjects enrolled in

pre-academic intensive English programs revealed

the positive effects of the programs on their writing.

Moreover, the findings of the present study are in

line with Raymonds (1995, cited in 15) study which

indicated that an accelerated teaching format could have

a beneficial effect on L2 writing development. The study

aimed to compare the effectiveness of the intensive

English program with the regular English program on

the learners oral and written language performance.

The analysis of the data revealed that although the

learners could develop their writing competence in both

intensive and regular programs, attending compressed

courses could help them achieve their goals in a shorter

period.

In summary, the present study suggests that

enhancing L2 writing through time-shortened courses is

not beyond the bounds of possibility. Hence, the results

reported in this study are in contrast to the claim of

intensive program opponents [20, 21] that accelerated

language courses are too rapid and compressed to be

beneficial for language learners. In addition, this study

does not support the findings of previous research [15].

Jacques-Bilodeau (2010) carried out a study on 15 high

school students attending an intensive English program

in Quebec in order to investigate the long-term effect of

intensive English courses on the learners language

knowledge development [15]. Jacques-Bilodeaus findings

showed that majority of the participants believed their

writing competence was far from the satisfactory level

[15].

Furthermore, as the analysis of the data revealed, the

kind of the teaching techniques used in the four-week

intensive intervention, including integrating writing and

other language skills and sub-skills, encouraging learners

to respond to the reading material, teaching them

paragraph and essay development skills, focusing on

both form and meaning, exposing them to different models

of genres and emphasizing revision and editing skills,

proved to be highly effective in assisting the L2 learners

with their writing enhancement. Additionally, a deep

analysis of the subjects writing indicated that the course

had an effective role in improving all the five aspects of

their writing; that is, organization, content, vocabulary,

1 grammar and mechanics.

1681

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

Thus, these findings are in sharp contrast to the

expressivists theoretical view that rejects any kind of

teacher intervention and solely emphasizes the

importance of peer evaluation. In other words, the

advocates of expressivism, like Elbow [22] and Moffett

[23], believe in a teacherless writing class where only the

writer, as the individual, matters and peers are the only

sources of responses since the teachers authority and

feedback hamper the natural relationship between the

writer and the reader.

The significant progress observed in the written

works of the participants of this study at post-test stage

also

backs up Hatlens [24] claim that teacher

intervention is necessary in writing classes to help

learners with their writing development. Hatlen

criticizes expressivist theory on the ground that it

wrongly supposes that students already have within

themselves everything they need in order to write well"

(citedin 25, p. 648). In addition, Bartholomae [26] also

emphasized the need for an active role of teachers in

composition courses and challenged Peter Elbows

pedagogical theory [22] in his Writing with Teachers: A

Conversation with Peter Elbow.

The necessity of teacher intervention was also

supported by Pauluss study [17] which compared the

effect of teacher feedback to peer feedback and

demonstrated that although peer feedback could be

beneficial for language learners, teacher feedback

could affect their performance more significantly.

Furthermore, Ferris [27] also reported positive results

associated with teacher intervention in her study,

which examined the influence of teacher feedback

on the students writing performance. Similarly, the

findings of Saitos [28] study, which was done on 39

students attending ESL intensive programs and an

ESL Engineering writing class, indicated the students

preference for teacher feedback. The data from the

questionnaire given to the subjects of his study

revealed that all types of providing teacher

feedback were preferred to peer and self-feedback.

On the whole, the significant improvement in the

writing performance of the participants in this

study proved that intensive teaching formats could be

highly beneficial for language learners in L2 learning

settings.

Another point worth noting is the effect of

integrating reading and writing skills. A wealth of

literature is available on the positive effect of

approaching reading and writing skills in a

transactional way. According to Flower et al. [29],

literacy is more than being able to read or to write;

it is the ability to use reading and writing skills in an

integrative way to achieve a purpose in the context at

hand. As Leki [30] argues,

If we use reading and writing reciprocally in L2

classrooms, focusing less on teaching language, reading,

or writing and more on allowing students to engage

intellectually with text, the engagement with text fosters a

view of reading and writing as active construction of

meaning. (p. 22)

The idea behind integrating reading and writing is

to teach the student to read like a writer and to

write like a reader [31]. Reportedly, although both

traditional and integrative methods could have a

positive effect on learners reading comprehension and

writing expression skills, integrating reading and writing

proved to be significantly more effective on the

experimental groups achievement and retention levels

[32]. Based on the findings of the present study, it seems

logical to assume that learners benefit from integrating

language skills.

CONCLUSION

The results showed that language teachers and

program developers should reconsider the role of

intensive courses. Based on the findings of this

study intensive programs can have a positive effect

on learners writing skills. As it is the case in

Malaysia students experience only a 45-minute

period every other week the effect of which is

negligible compared with that of an intensive course.

In Malaysia, researchers have pointed out the

students unsatisfactory writing skills after years of

taking English lessons at school [33, 34]. Based on

the results of the present study, it seems logical to argue

that these students should go through writing courses

more frequently than they do.

Another important implication that this study

has is the strong relationship between reading and

writing. As mentioned earlier, the intensive program

consisted of different components one of which was

called Reading and Writing. The students went

through this component twice a day. Reading is regarded

as one of the best pre-writing activities which can engage

the learner in writing (as a response) [35]. In addition, from

1682

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

a pedagogical perspective, suitable reading passages can

provide useful models for student writers by showing

them the characteristics of an acceptable piece of writing.

The related literature emphasizes integration of reading

and writing skills [36] and the findings of this study, at

least in part, indicate its positive outcome.

The study may have useful implications for language

instructors but research-wise it has some limitations.

However, a number of points should be considered before

such findings can be generalized. One of the limitations of

this study was the short time interval (one month)

between the pre- and post-tests. This could control the

threat of maturation effect, but the pre-test itself could

have helped the participants to write better at the

post-test. Further studies with more sophisticated

designs, replicating the procedure followed in this

research, may lead to more useful findings. Adding a

delayed post-test to the design or making it more in-depth

through qualitative research methods could also result in

richer findings.

REFERENCES

1. Mukundan, J., 2003. An evaluation of the certificate

in the English language course for jobless graduates

in the Graduate Training Scheme (GTS). Serdang:

UPM.

2. Mukundan, J., E.H. Mahvelati and Nimehchisalem,

V. (2012). The effect of an intensive English program

on Malaysian Secondary School students language

proficiency, English Language Teaching, 5(11): 1-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n11p1

3. Jacobs, H., S. Zingraf, D. Wormuth, V.F. Hartfiel and

J. Hughey, 1981. Testing ESL composition: A

practical approach. MA: Newbury House Publishers.

4. Tribble, C., 1996. Writing. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

5. Holmes, N., 2009. The use of a process-oriented

approach to facilitate the planning and production

stages of writing for adult students of English as a

Foreign or Second Language. Retrieved August 13,

2012, from: http://www. developing teachers.

com/articles_tchtraining/processw1_nicola.htm

6. Matsuda, P.K., A.S. Canagarajah, L. Harklau,

K. Hyland and M. Warschauer, 2003. Changing

currents in second language writing research: A

colloquium. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12:

151-179.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S10603743(03)00016-X

7. Onozawa, C., 2010. A Study of the Process Writing

Approach-A Suggestion for an Eclectic Writing

Approach. Retrieved August 25, 2012 from:

http://www.kyoai.

ac.jp/college/ronshuu/no10/onozawa2.pdf

8. Ismail, S.A.A., 2011. Exploring students perceptions

of ESL writing. English Language Teaching,

4(2): 73-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n2p73

9. Moghaddam, M.M. and S.H. Malekzadeh, 2011.

Improving L2 writing ability in the light of critical

thinking. Theory and Practice in Language

Studies, 1(7): 789-797. http://dx.doi.org/10. 4304/tpls.

1.7.789-797

10. Burton, S. and P. Nesbit, 2002. An analysis of student

and faculty attitudes to intensive teaching. Paper

presented at the celebrating teaching and Macquire,

Macquire University.

11. Buzash, M.D., 1994. Success of two-week intensive in

program in French for superior high school students

on a university campus. Paper presented at the

Annual Meeting of the Central State conference on

the Teaching of Foreign Languages, Kansas City,

MO. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED

403 740)

12. Daniel, E.L., 2000. A review of time-shortened courses

across disciplines. College Student Journal, 34: 298308.

13. Hong-Nam, K.

and

A.G.

Leavell, 2006.

Language learning strategies of ESL students in

an intensive English learning context. System,

34(3): 399-415. http://dx.doi. org/10. 1016/j.

system.2006.02.002

14. Lightbown, P.M. and N. Spada, 1989. Intensive ESL

Programmes in Quebec Primary Schools. TESL

Canada Journal, 7(1): 11-32.

15. Jacques-Bilodeau, M., 2010. Research project: A

study of the long term effects of Intensive English

programs on secondary school ESL students.

Retrieved on July 27, 2012, from www.csbe. qc. ca/

projetrd / doc_projet/marie_jac_bil_2010.pdf

16. Carson, J.E. and P.A. Kuehn, 1992. Evidence of

transfer and loss in developing second language

writers. Language Learning, 42(2): 157-182. http://dx.

doi. org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1992.tb00706.x

17. Paulus, T.M., 1999. The effects of peer and teacher

feedback on student writing. Journal of Second

Language Writing, 8(3): 265-289. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/S1060-3743(99)80117-9

1683

World Appl. Sci. J., 22 (12): 1677-1684, 2013

18. Hamp-Lyons, L., 1990. Second language writing:

Assessment issues. In: B. Kroll (Ed.), Second

language writing: Research insights for the

classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

19. Gleason, J., 1986. Economic models of time in

learning. Unpublished PhD, University of Nebraska.

20. Gallow, M.A. and M. Odu, 2009. Examining the

relationship between class scheduling and student

achievement in college algebra. Community College

Review, 36(4): 299-325. http://dx.doi. org/10.

1177/0091552108330902

21. Nasiri, E. and N. Shokrpour, 2012. Comparison of

intensive and non-intensive English courses and

their effects on the students performance in an EFL

university context. European Scientific Journal, 8(8):

127-137.

22. Elbow, P., 1973. Writing without teachers. London:

Oxford University Press.

23. Moffett, J., 1968. Teaching the universe of discourse.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

24. Hatlen, B., 1988. Michel Foucault and the

Discourse[s] of English. College English, 50: 786-801.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/377681

25. Fishman, S.M. and L.P. McCarthy, 1992. Is

expressivism dead? Reconsidering its romantic roots

and its relation to social constructionism. College

English 54(6): 647-661. http://dx. doi.org/10.

2307/377772

26. Bartholomae, D., 1995. Writing with Teachers: A

Conversation with Peter Elbow. College Composition

and Communication 46(1): 62-7. http://dx. doi. org/10.

2307/358870

27. Ferris, D.R., 1997. The influence of teacher

commentary on student revision. TESOL Quarterly,

31(2): 315-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3588049

28. Saito, H., 1994.Teachers' practices and students'

preferences for feedback on second language writing:

A case study of adult ESL learners. TESL Canada

Journal, 11: 46-70.

29. Flower, L., V. Stein, J. Ackerman, M.J. Kantz, K.

McCromick and W.C. Peck, 1990. Reading to write:

Exploring a cognitive and social process. New York:

Oxford University Press.

30. Leki, I., 1993. Reciprocal themes in ESL reading and

writing. In J. G. Carson and I. Leki (Eds.), Reading in

the composition classroom: Second language

perspectives (pp: 9-32). Boston: Heinle and Heinle

Publishers.

31. Kroll, B., 1993. Teaching writing is teaching reading:

Training the new teacher of ESL composition. In J.G.

Carson and I. Leki, (Eds.), Reading in the composition

classroom: Second language perspectives (pp: 61-82).

Boston: Heinle and Heinle Publishers.

32. Durukan, E., 2011. Effects of cooperative integrated

reading and composition (CIRC) technique on

reading-writing skills. Educational Research and

Reviews, 6(1): 102-109.

33. Pandian, A., 2006. Whatworks in the classroom?

Promoting literacy practices in English. 3L:Language,

Linguistics, Literature, 11: 1-25.

34. Ramaiah, M., 1997. Reciprocal teaching in enhancing

the reading ability of ESL students at the tertiary

level. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of

Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

35. McGinley, W., 1992. The role of reading and writing

while composing from sources. Reading Research

Quarterly,

27(3):

227-248.

http://dx.

doi.

org/10.2307/747793

36. Campbell, C., 1998. Teaching second language

writing: Interacting with text. Boston: Heinle and

Heinle Publishers.

1684

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Vijanabhairava TantraDocument23 paginiVijanabhairava TantraSreeraj Guruvayoor S100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Psychoanalytical Impact On O Neill S Long Day S Journey Into NightDocument2 paginiPsychoanalytical Impact On O Neill S Long Day S Journey Into NightKinaz Gul100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Log Ucsp RevisedDocument53 paginiDaily Lesson Log Ucsp RevisedAngelica Orbizo83% (6)

- Handbook of Organizational Performance PDFDocument50 paginiHandbook of Organizational Performance PDFdjquirosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership Study BenchmarkingDocument7 paginiLeadership Study BenchmarkingPaula Jane MeriolesÎncă nu există evaluări

- RCOSDocument3 paginiRCOSapi-3695543Încă nu există evaluări

- Day3 Marcelian ReflectionDocument13 paginiDay3 Marcelian ReflectionAva Marie Lampad - CantaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Candidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To QuestionsDocument2 paginiCandidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To Questionsmbrnadine belgica0% (1)

- Alcohol Is A Substance Found in Alcoholic Drinks, While Liquor Is A Name For These Drinks. ... NotDocument7 paginiAlcohol Is A Substance Found in Alcoholic Drinks, While Liquor Is A Name For These Drinks. ... NotGilbert BabolÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Civil Aviation Organization Vacancy Notice: Osition NformationDocument4 paginiInternational Civil Aviation Organization Vacancy Notice: Osition Nformationanne0% (1)

- Chapter 1: Professional Communication in A Digital, Social, Mobile World 1. Multiple Choices QuestionsDocument4 paginiChapter 1: Professional Communication in A Digital, Social, Mobile World 1. Multiple Choices QuestionsNguyễn Hải BìnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Causal EssayDocument8 paginiCausal Essayapi-437456411Încă nu există evaluări

- EnglishDocument7 paginiEnglishganeshchandraroutrayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human DevelopmentDocument4 paginiHuman Developmentpeter makssÎncă nu există evaluări

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachDocument1 paginăGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachIrene Tayone GuangcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection EssayDocument4 paginiReflection Essayapi-266336267Încă nu există evaluări

- Interactive Module 9 WorkbookDocument21 paginiInteractive Module 9 WorkbookIuliu Orban100% (1)

- Developing The Leader Within You.Document7 paginiDeveloping The Leader Within You.Mohammad Nazari Abdul HamidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Format. Hum - Functional Exploration Ofola Rotimi's Our Husband Has Gone Mad AgainDocument10 paginiFormat. Hum - Functional Exploration Ofola Rotimi's Our Husband Has Gone Mad AgainImpact JournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Themes Analysis in A NutshellDocument2 paginiThemes Analysis in A Nutshellapi-116304916Încă nu există evaluări

- Engaging D'aquili and Newberg's: The Mystical MindDocument8 paginiEngaging D'aquili and Newberg's: The Mystical MindPatrick Wearden ComposerÎncă nu există evaluări

- WEEK 1 DLL Math7Document9 paginiWEEK 1 DLL Math7GLINDA EBAYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speech On MusicDocument2 paginiSpeech On MusicPutri NurandiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proficiency Testing RequirementsDocument5 paginiProficiency Testing RequirementssanjaydgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bert Johnson Letters of Support in Sentencing To Judge Leitman, MIEDDocument52 paginiBert Johnson Letters of Support in Sentencing To Judge Leitman, MIEDBeverly TranÎncă nu există evaluări

- USM PLG 598 Research Thesis Preparation Tips and Common ErrorsDocument10 paginiUSM PLG 598 Research Thesis Preparation Tips and Common ErrorsPizza40Încă nu există evaluări

- BPRS PDFDocument2 paginiBPRS PDFAziz0% (1)

- DLL For COT 2ndDocument3 paginiDLL For COT 2ndAllan Jovi BajadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 1 BARC CaseDocument14 paginiGroup 1 BARC CaseAmbrish ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subject Offered (Core and Electives) in Trimester 3 2011/2012, Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia UniversityDocument12 paginiSubject Offered (Core and Electives) in Trimester 3 2011/2012, Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia Universitymuzhaffar_razakÎncă nu există evaluări