Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

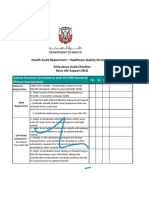

Guidlines Ambulance Operation PDF

Încărcat de

IdarosyadaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Guidlines Ambulance Operation PDF

Încărcat de

IdarosyadaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

NHS

Modernisation Agency

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Best Practice Guidelines on

Ambulance Operations

Management

www.modern.nhs.uk/ambulance

Improvement Partnership for

Ambulance Services (IPAS)

NHS Modernisation Agency

Third Floor,

Heron House,

322 High Holborn,

London,

WC1V 7PW.

Tel: 0207 061 6820

The NHS Modernisation Agency is

part of the Department of Health

NHS

Modernisation Agency

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

READER INFORMATION

Policy

HR/Workforce

Management

Planning

Clinical

Estates

Performance

IM & T

Finance

Partnership Working

Document Purpose

For information

ROCR Ref:

Gateway Ref: 3423

Title

Operations Management for

Ambulance Services

Author

DH/NHS MA/IPAS

Publication date

November 2004

Target Audience

Directors of Operations

Circulation List

Description

Contents

Introduction

Ambulance Trust CEs

Demand Based Cover/Dynamic Cover Plan

A document which covers key tactical

deployment facts, points of learning

and issues which zero starred and CHI

challenged trusts may appreciate.

Utilising Resources:

Cross Ref

N/A

Superseded Docs

N/A

Action Required

N/A

Timing

N/A

Contact Details

Phoebe White

NHS MA/IPAS

3rd Floor, Heron House

High Holborn

WC1V 7PW

020 7061 6820

www.modern.nhs.uk/ambulance

www.modern.nhs.uk/scripts/default.

asp?site_id=60&id=17018

Single Responders

Deployment Regime

Urgent Cases

11

Activation Times

12

Ambulance Turnaround Times

13

Intermediate Tier

14

Helicopter Emergency Medical Service

15

British Association of Immediate Care Schemes (BASICS)

16

Community and Corporate Responders

17

Pre-Determined Response

17

Deployment of Officers/Managers to Serious or Untoward Incidents

18

Performance Updates

18

For Recipients Use

This document is also available on

the Improvement Partnership for

Ambulance Services (IPAS) website

at www.modern.nhs.uk/ambulance

Special Measures

19

Roles

20

Leadership and Communication

20

Managing Rotas

21

Appendix 1: National Standards, Local Action: Health and Social Care

Standards and Planning Framework 2005/06-2007/08.

22

Appendix 2: Definitions for Completion of KA34

23

Appendix 3: Table of Contributors

24

Appendix 4: Definitions and Useful Information

25

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Introduction

The revised National Standards, Local

Action: Health and Social Care

Standards and Planning Framework

2005/06-2007/08 sets out the

framework NHS organisations and

social service authorities are to use in

planning for the next three financial

years and the standards which all

organisations should achieve in

delivering NHS care. Appendix 1of the

National Standards, Local Action

document, lists the existing

commitments to be maintained and

achieved by March 2005 (see

Appendix 1 of this document). These

include the ambulance response time

measures for Category A and B.

Although it is recognised that the first

priority for a Trust is to achieve and

sustain the key target of responding to

75% of all calls categorised as

immediately Life-Threatening within 8

minutes, performance improvement

should be designed to address wider

performance measures as indicated by

the Core and Developmental

Standards in the National Standards,

Local Action document. These include

improving clinical outcomes,

particularly those, which are the

subject of National Service

Frameworks. In addition, there is a

need to comply with Improving

Working Lives, Health and Safety

legislation, Controls Assurance and the

Clinical Governance framework and

other guidance.

This document aims to offer

information and good practice

examples in terms of Ambulance

Operations Management and has been

developed with generous assistance

from Greater Manchester Ambulance

Service, Hereford and Worcester

Ambulance Service and Kent

Ambulance Service. These

organisations experienced a trend of

significant service improvement of up

to 40% by implementing the best

Demand Based Cover/Dynamic Cover Plan

practice cited in this document to

achieve and maintain the Category A

75% of calls within 8 minutes target.

Demand Based Cover relies on

monitoring and analysing historic

activity and extrapolating this data

to predict future demand. It is an

important and useful tool when

drawing up rotas and predicting

when and where to deploy vehicles.

The principle underlying this

approach is to ensure that all

despatch points are situated in areas

where they can reach high priority

Category A scenes within 8 minutes

and that they have the necessary

available resource to meet expected

demand situated within them. They

are often not at the sites of existing

ambulance stations which were

located for different reasons.

In writing this document we recognise

that all trusts experience different

challenges and constraints and that

some issues may impact on an

organisations ability to implement the

suggested good practice. However,

evidence, some of which is presented

in this document, has shown that

implementing such good practice ideas

can lead to real and sustainable

improvements.

The contributors to this document

from Greater Manchester, Hereford

and Worcester and Kent, listed in

Appendix 3, are happy to be

contacted for further guidance on

implementing these practices. These

best practice guidelines are also

covered in more depth in the System

Status Management training

programme, which is run by Keele

University.

It is recommended that the

information and good practice offered

within this document be adopted

within a wider whole systems change

and a service improvement approach

that responds to the Department of

Healths Reforming Emergency Care

agenda. 999 calls to ambulance

services have increased over the years,

(7.7% for the Service as a whole last

year, however some individual Trusts,

for example Bedfordshire and

Hertfordshire, saw increases of 20%)

and consequently this has had an

impact on the demand placed on the

service and the ability of trusts to

meet targets. In June 2002, Margaret

Edwards, Director of Access and

Choice at the Department of Health,

wrote a letter to all ambulance trusts

entitled Delivering the NHS Plan

Strengthening Accountability:

Appropriate Use of Ambulance

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Services which highlighted local

action that should be taken in

response to malicious and hoax callers

and in response to 999 calls where

sending an ambulance would be

appropriate. This led to many services,

for example London Ambulance

Service, developing a no send policy

for such instances.

Through the modernisation of

ambulance services and the

introduction of new roles, ambulance

trusts are in the position to respond to

the increased demand more

innovatively (for example, it may not

be an appropriate response to take all

999 callers to A&E. Some Category C

callers could be more appropriated

treated at Walk in Centres, Minor

Injuries Units or by links to NHS Direct

etc). Improved relationships with

Primary Care Trust commissioners of

emergency ambulance services and

non emergency patient transport

services can also help ensure that

ambulance services are commissioned

and used appropriately. More

information on this subject is available

in an IPAS document around

commissioning entitled Driving

Change (please refer to Appendix 4).

The annual demand for call outs must be

identified, taking into account the reason

for the call, the category (ref Healthcare

Commission Performance Rating Targets

2004/5), the area of call out etc.

ANALYSE DEMAND

OVER A PERIOD

OF TIME PAST

BREAK DOWN

INTO DEMAND

PER UNIT HOUR

There are various command and control

or stand alone software solutions on the

market to help with demand analysis.

These can cost as little as 7,000.

Contact a neighbouring service or a 3

star service for advice on those systems

they use. Contacts from the services in

Appendix 3 can also provide guidance.

An excel spread sheet can be used as a

backup.

The demand analysis then needs to be

extrapolated to produce weekly rotas,

detailing the demand per hour (over 168

hours) for each week of the year. This

will form the baseline for the generic

rota. Adjustments for known increases

in demand will need to be imposed on

top for example seasonal demand (the

Christmas period and school holidays

etc) and large scale public events etc.

The demand per unit hour should be

mapped over a geographic area to

enable the most suitable areas for

despatch points to be identified.

DEPLOY AMBULANCES

ACCORDING TO THESE

HOURLY PATTERNS

The despatch points generated by the

unit hour demand should be located

within 1.5km or 6 minutes response time

from the centre of the area of high

demand. (It is recommended not to

work on an 8 minutes response time as

this does not allow for activation time. It

is established practice for trusts to aim

for a 4 minute response time as this

increases the chance of a positive clinical

outcome for the patient suffering from

cardiac arrest).

Note: Demand varies on each day of the

week and by each hour of the day. The

resources deployed at each despatch

point should reflect these fluctuations in

demand.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 5

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Good Practice Example:

In 2001, Hereford & Worcester employed a software company to help them work out their

demand analysis and deployment strategy.

The use of the software let to the consistent achievement of life threatening best

practice measures.

Vehicles are no longer solely stationed at ambulance stations.

Involve staff and unions in any

discussions around reviewing the

demand and deployment process

from the beginning. Its best to be

open, honest and transparent

about the process

Maximum priority cover

should be provided at all

times on all points

DISPATCH POINTS

Try not to deploy more

than one available resource

on any of the despatch points

unless the unit hour

demand dictates

Remember to take into account

rest times and staff changeover

times, including briefing and

debriefing on station management

issues and incidents when doing

the hourly plan

USEFUL TIPS

Talk to neighbouring

ambulance services or staff at 3

star Trusts about software to

analyse and predict demand.

Your demand plan will dictate

the priority of your despatch

points. When moving single

crewed staff from one despatch

point to another in order to

establish a crew, move staff to

the higher priority station.

When priority points have been

covered, move additional

resources to support the highest

priority points as they represent

the highest demand. Also to

cover meal breaks, training etc.

Despatch points dont have to

be ambulance service owned

some services use primary

healthcare facilities, hence

integrating with the local health

economy. Others use fast food

outlet premises, other

emergency services or military

bases too. Approach these and

others to see if you can share

their premises for a nominal fee.

This approach is not the best for

all services and it is advisable to

consult staff and unions about

any planned changes.

Remember:

The Control Room can help in managing demand.

An ambulance may not be necessary for all 999

callers some services employ an NHS Direct Nurse

or other suitably trained staff to offer alternative

care suggestions to Category B or C callers.

Remember:

Not all cases responded to will require treatment at

hospital A&E. It may be more appropriate to refer

patients to alternative care centres, (for example

Minor Injury Units, Walk in Centres or to Treat and

Refer) or develop protocals which allow direct

access to Coronary Care Units, Stroke Units etc.

Remember - Least Vehicle

Moves. This is time saving when

moving vehicles between

despatch points, when adopted

to vehicles that have the least

distance to travel.

Do not ask resources to patrol

mid points between despatch

points.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 7

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Utilising Resources

USEFUL TIPS

Either ambulances or single

responders can cover priority

despatch points however,

there should not be more than

one available resource in each

despatch point at any given

time.

Single Responders

Ambulance single responders (paramedic or technician) in cars, motor bikes,

or bicycles have an obvious advantage over ambulance vehicles. Bikes and

cars can negotiate the traffic faster and easier and can be up to 50% faster

than an ambulance.

AMBULANCE VEHICLE

showing 8 minutes

response time on

Can assume BIKE/CAR

BIKE/CAR

AND

showing 8 minutes

response time on

the CAD

In these circumstances

the responder should

continue to the call.

However, if a subsequent

Red call is received within

their vicinity whilst en

route to an Amber or

Green call, they must be

redeployed as priority.

time should

be 4 MINUTES

the CAD

Depending on the geographical nature of the service, single responders

should be targeted at Category A calls. If the call is confirmed as an Amber

once en route, they can be stood down. However, the responders can be

utilised if attending cases that will maintain their skills or levels of utilisation

and thus benefiting patient care, for example:

ONE

actual response

MEANS

TWO

Once on scene of an

Amber or Green call the

responder must be ready

and prepared to respond

to any subsequent Red

call as soon as possible,

and must keep the

control room updated

regarding the patients

condition, in particular if

the ambulance can be

stood down.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Chest Pain

Diabetic

Epileptic

Unconscious patient

Falls over 6 feet

Road Traffic Crash

THREE

A Single Responder is

seen as available

after the arrival of

an ambulance or any

other professional that

they hand the patient

over to.

Motorcycles can provide great

advantages of speed and

versatility in built up areas and

road networks congested by

slow or stationary traffic,

therefore it is essential they

patrol high traffic density areas

during rush hours and any

location where a gridlock

situation has occurred.

Motorcycles are also useful at

large scale public events

where there will be a high

density of people e.g. open-air

events.

Consider fitting child seats to

the rear of responder cars to

enable vehicles to be able to

transport children under the age

of 4 years.

Suitably trained officers and

managers can be utilised as

first responders to respond to

Category A calls if they are in

the vicinity.

Officers and managers should

keep their blue lights

attached to their vehicles when

on duty and when travelling to

duty. This practice can save up

to 45 seconds! (Trusts should

inform the Police of this

practice).

Deployment Regime

Calls should be allocated to the

nearest available resource in the

following priority:

Cat A

Red

Single Responder

Emergency Ambulance,

Intermediate Tier

Community/Corporate

Responder

Cat B

Amber

Single

Responder

Emergency

Ambulance

Local

Category C

Arrange

-ments

Green

Single

Responder

Emergency

Ambulance

Good Practice Example:

Kent Ambulance Service anticipate that utilising their

intermediate tier will increase their response rates

by 2.1%

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 9

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Deployment Regime

continued:

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Urgent Cases

Urgent journeys should be allocated a vehicle(s) as soon as possible after

they are received in the control room, in the following priority order:

PTS / ACVS

Urgent

Admissions/

Transfer/

Discharge

Discharges

Routine

Admissions

Intermediate Support

initially / PTS, then

Emergency Ambulance if

necessary. ACVS can be

used if the GP agrees

PTS/Intermediate

Support/ACVS initially,

then Emergency

Ambulance if necessary

PTS/Intermediate

Support/ACVS initially,

then Emergency

Ambulance if necessary

On occasions, this may mean that a vehicle

from one area is deployed to another area to

deal with the urgent case.

Intermediate tier and PTS vehicles, no matter

what their location, should be deployed in

preference to A&E vehicles

It may also be worth slightly delaying the

deployment of a resource to an urgent case

to allow time for an intermediate crew to

clear and then be allocated again, rather

than commit an A&E resource

West Midlands Ambulance Service are introducing a Response Generator based on a

simple philosophy of treating the sickest patients first. The Trust is currently working towards a

process of managing Emergency and Urgent calls via a single stream, so that patients are

allocated an appropriate response and resource according to their presenting clinical

condition, irrespective of origin or entry into the system. When fully realised, the Response

Generator, seeks to grade calls into priorities such as: Immediate, Urgent, Sequential and Routine,

with the relevant response delivered by differing members of the health care team, such as, NHS

Direct, primary care and the ambulance service, from paramedics to patient carers, and would

serve to progress the Reforming Emergency Care agenda.

Current identified priority areas

requiring emergency cover (it may

be more appropriate to send a

vehicle which will need to travel

through an uncovered area to

reach the urgent patient).

Whether the crew is due a meal

break.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Emergency vehicle from

nearest lower priority

despatch point

Good Practice Example:

The selection of an A&E vehicle for

deployment to an urgent call will

take into account the following

points:

10

Intermediate crew

(see page 14)

Whether the crew are

approaching the shift end time.

It is good practice that, as well as

continuing to determine the latest

time by which the patient should be

admitted to hospital, that call takers

check if we have an ambulance

available before that time, is the

patient ready to admit now?

NSF/CHD - Chest Pain

Any Cardiac related chest pain

requested as an urgent, must

immediately be upgraded, by

the control room/

communication centre to an

emergency and responded

to accordingly

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 11

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Good Practice Example:

Good Practice Example:

Hampshire Ambulance Service introduced a new procedure for GP Urgents in December

2003 with the aim of reducing response times and ensuring the most appropriate

resources are dispatched in relation to the patients clinical profile. Urgent bookings can

only be booked by a doctor or nurse caring for the patient to enable booking staff to take the

necessary information about the patients condition. Urgent transfers are taken with a pick up

time of two hours (120 minutes) or an emergency (999) transfer may be requested. The

Communications Team Leader (CTL) will be informed of any cases where an ambulance will not

arrive to collect the patient within 80 minutes of the initial request. In such case the CTL will

initiate a comfort call to the patient to assess if their condition has changed/worsened. If it

has, an emergency ambulance (999) will be dispatched. If not the patient is informed that an

ambulance will be with them as quickly as possible. If the ambulance has not arrived within 100

minutes, the call is immediately upgraded to an emergency (999). This procedure has since

seen a marked improvement in performance (96.2% average over the 6 months since the

implementation) and a notable reduction in complaints from patients, GPs and acute units.

Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Ambulance and Paramedic Service has taken advantage of

the fact that BT allocate telephone dialling codes and the first part of telephone numbers

geographically by holding a database in the bespoke Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD)

system identifying the telephone exchange areas to which numbers relate. As a

consequence, when 999 calls come from a BT land line number, the CAD automatically crosschecks the database and, if a match is found, displays the general area in which the telephone

number is located.

Activation Time

Ambulance

Turnaround Times

Reduction in activation time is one of the most effective ways to improve

response times. It is established practice for trusts to aim for an activation

time of 3 minutes, 95% of the time.

3 minutes

Clock start

5 minutes available for the journey if necessary

Activation

On scene

It is recommended that a faster activation time standard is aimed for as this

allows for increased journey time to meet the 8 minute target. The easiest

way to reduce response times is to deploy vehicles as soon as the area of the

incident is identified by the callers telephone number.

1.5 minutes

Clock start

6.5 minutes available for the journey if necessary

Activation

USEFUL TIPS

Audit the activation times at each despatch point and then customise

the standard for each to ensure deployed vehicles reach incidents in the

area within 8 minutes.

12

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

On scene

This has the benefit of allowing the relevant dispatcher to commence the allocation of a

vehicle process while the call taker is ascertaining the exact location, thus shaving

precious time from the Activation process.

Configuration of the database was relatively fast as BT readily provided the information needed

and the bespoke CAD software had the capacity to deal with the database already.

Ambulance turnaround times (ie the

time between an ambulance arriving

at the hospital receiving department

and the time of handing over the

patient to the care of hospital staff)

can impact on an ambulance trusts

ability to free up capacity and

respond to other patients. The

Sitreps Guidance and Definitions

2003/04 state that 15 minutes is

thought to be a reasonable time to

allow completion of handover at

A&E. However, it is recognised that

the turnaround times vary in

different areas and that they are a

problem in some counties.

Some trusts are working with

hospitals to agree solutions to the

problem. Greater Manchester

Ambulance Service have

implemented the following

approach:

Good Practice Example:

GMAS have put in place an Escalation Policy which is

triggered when the combined at hospital time of one or

more ambulances at a receiving unit/hospital is more than two

hours, and the delay is due to the inability of the crew to

transfer the patient into the care of hospital staff. The

Paramedic Emergency Control (PEC) Duty Manager continually

monitors the situation at hospitals and mobilises a Local Officer

to the affected hospital once pressures start building and the

trigger time is reached.

The Local Officer liaises with the hospital department heads and

bed managers to assess the situation and offer any help or

takes the necessary action to ease the situation for example

ensuring all ambulance discharges/transfers from the receiving

unit/hospital are actioned immediately. These actions may

require action to free bed space and create capacity at other

acute trusts.

If it is felt that the problems cannot be resolved within a

reasonable time (for example 15 minutes), the GMAS General

Manager is contacted and plans to divert ambulances will be

implemented.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 13

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Intermediate Tier

Many Services operate an intermediate tier service targeted at GP Urgents.

These can be an additional resource when targeting Category A calls,

however the core function of most are:

Routine admissions, transfers and discharges.

Urgent admissions.

Hospice admissions.

Discharges home.

Urgent transfers.

In addition, some services also use the intermediate tier to respond to some

Category C calls, for example to pick up non injury or in-house assistance.

Depending on the training of the staff, the intermediate tier can also be

utilised for:

Post assessment transport.

Emergency transfers.

PTS may also be deployed to render assistance

to an A&E crew requiring assistance with lifting

or handling their patient; (using emergency

procedures if necessary).

After the patient has been assessed and it

is clear that the PTS crew can provide their

individual care requirements, the A&E

attending resource should be stood down. It

is permissible for the PTS crew to transport

the patient to A&E or other appropriate

location in these circumstances

PTS crews may also be deployed to a

confirmed RED call, if they are the closest

resource in order to render aid until an A&E

crew or single responder arrives. Suitably

trained and equipped PTS crews may

also be deployed to Category A calls

Helicopter Emergency

Medical Service (not

applicable to all services)

If an Air Ambulance is available for

deployment it can be targeted at any

suitable calls that have been

categorised as RED (life threatening)

under the prioritisation system. The

following examples indicate other

incidents where the Helicopter

Emergency Medical service could be

deployed:

All Road Traffic Accidents

involving:

Persons reported trapped.

Persons thrown or ejected from

vehicles.

Possibility of fatalities involved.

Any road traffic accident involving

more than 3 vehicles.

Other means of entrapment:

Any suspected burial or cave-in

incidents.

Any other suspected types of

entrapment.

Traumatic amputations.

High velocity blasts,

penetrating injuries, industrial

accidents, etc taking into

account the type of

situation i.e. firearms.

Collapse/cardiac problems/

chest pains (with long scene to

hospital times or long ETA of

ambulance if cardiac related).

Lower priority calls in remote

or difficult to access by road

areas.

In accordance with best practice in

patient care, the transport time of critically ill

patients or those involved in entrapment MUST be

kept to an absolute minimum. For this reason it is

recommended to land the helicopter at all

confirmed entrapments to assess the patients

suitability for air transfer

In addition to the above they can

also be essential in the transfer

of:

Clinical personnel to the scene of

an incident.

Seriously ill patients being

transferred from one hospital to

another for specialist treatment.

If the aircraft is unable to fly (e.g. due to

mechanical or weather conditions), consider

deploying the paramedic staff in a car to

utilise staff on duty

Good Practice Example:

Westcountry Ambulance Service have in place a policy that minimises the risks of lifting for

ambulance crews attending patients at care homes that come under the auspices of the National

Care Standards Commission (NCSC). This policy has the support of the Care Standards Agency

and the Health and Safety Executive and those care homes who call the ambulance service

out unnecessarily or only to lift uninjured patients (because of an absence of lifting equipment

or trained staff) can be reported to the NCSC who will follow the incident up if appropriate.

14

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 15

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

BASICS - British

Association of

Immediate Care

Schemes (for those who

operate the BASICS

scheme)

BASICS are a team of doctors who

are trained in pre-hospital care.

They carry life support equipment

and complement the paramedic

response at an incident. Members of

BASICS generally arrange the criteria

for call out locally by the ambulance

communications centre/control

room. Most schemes cover the

following list:

Road Traffic Crash (RTC) with

reported entrapment of any

kind.

RTC with ejection.

RTC with vehicle overturned.

RTC death in vehicle and other

casualties.

Fire with reported persons on

scene.

Paediatric cardiac arrest.

When an ambulance crew requires

immediate BASICS assistance on

the scene of an incident.

When the communications centre

has strong reason to believe that

BASICS assistance may be

beneficial to any casualtys care

prior to the true and full extent of

the incident being known.

When recognition of life extinct

is excluded for staff and a

BASICS member is attending.

When a request is made via the

communications centre from

another emergency service for

the attendance of a scheme

member.

In the event of a Major Incident

or Major Incident Standby

being declared.

16

Good Practice Example:

BASICS in Sussex will attend incidents at the instigation of

the Emergency Patient Communications Centre (EPCC) at

Sussex Ambulance Service. It is the responsibility of the

allocator on duty initially but also the Duty Communications

Officer to recognise when BASICS should be alerted to an

incident. BASICS are called out by pager reading EPCC

Respond Red followed by the location, type of incident, where

Sussex Ambulance are responding from and the incident

number. BASICS will be stood down if, once at the scene, the

paramedics determine they are not required.

In Sussex, it has been agreed that BASICS can be called if a crew

request them, if any incident sounds potentially serious or if

EPCC staff feel it appropriate. However, they will always be

called out for RTC with entrapment, RTC with ejection, RTC

where a vehicle has overturned and RTC involving a fatality.

Good Practice Example:

USEFUL TIPS

BASICS should not be used when:

If waiting for the scheme

members attendance, would

delay the transfer of the

casualty by the ambulance

service to hospital and/or cause

further foreseeable harm to the

casualty.

When the attendance of a

police surgeon would be more

appropriate.

When the attendance of the

patients GP or other primary

care provider would be more

appropriate.

When the attendance of a

scheme member is as a

substitute for the attendance of

the ambulance service.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Some services, e.g. GMAS,

operate with good success, a

diagnostic of death

procedure which results in

crews leaving from such

incidents faster, thereby

rendering themselves available

for other calls.

Community and

Corporate Responders

Many services operate a community

single/ first responder scheme, these

operate within predefined

boundaries, and are deployed when

Category A calls are received within

this boundary.

Consideration must be given to

providing timely support and, if

necessary, counselling to community

responders following incidents.

Agree Volunteer Contracts with the HR

department to set out the expectations of each

party, and the entitlements of the volunteers are

stated for example access to counselling and

occupational health schemes.

Pre-Determined Response

Some services have developed a predetermined response to improve

patient care and staff welfare.

An initial pre-determined response of

two resources would always be

deployed to the following;

Cardiac arrests.

Maternity cases if a multiple

birth is expected.

Suspected serious or entrapment

RTCs or multiples casualty

incidents.

Major Incidents at international

airports.

The two resources can be either

2 x ambulances or an ambulance

and single responders.

Crews should be informed if any additional

resources are being deployed in association

with them. This will allow for enhanced

communication and the standing down of

additional resources at an early stage

if not required

In addition a resource being deployed to

back up the original response should be

notified that they are the second or more

crew / resource

Good Practice Example:

Surrey Ambulance Service have a Pre-determined Response in place for the expected

home delivery of twins. The Emergency Dispatch Centre (EDC) will immediately dispatch the

nearest two ambulances to such an incident. The EDC will ask the caller for the details of the

hospital that the expectant mother is booked in to and then call the delivery suite to inform them

that paramedics are attending the expected home delivery of twins and that a midwife may be

required. The EDC will consider the possibility of a midwife requiring transport and move

emergency cover appropriately. The cover may be an ambulance, single responder or Trust

Manager. The first arriving ambulance crew will inform the EDC if a midwife is required, enabling

the EDC to either stand down the midwife or arrange transport (if required) to get the midwife to

the scene.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 17

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Deployment of

Officers/Managers to

Serious or Untoward

Incidents

Officers/Managers must be notified

at all times of the following

incidents:

Crew requests for officer

involvement.

Major Incident, (standby or

declared).

Three or more ambulances

required on scene.

Multiple casualties (over three

patients).

Confirmed entrapments likely to

be more than 20 minutes.

Injury to staff on duty.

Injury to patient whilst in trust

care.

Any incident of a dangerous or

hazardous nature.

Serious malfunction of equipment

that requires completion of

incident reporting procedure.

Any road traffic accident, no

matter how minor, involving trust

vehicles.

Civil disorders, terrorist attacks,

bomb/suspect device.

Fire calls with confirmed persons

reported.

Damage to or from trust property

or vehicles (to include theft of

vehicle).

Confirmed fire at

hospital/nursing/residential

home site.

Confirmed fire at any trust

property.

18

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Performance Updates

Good Practice Example:

All managers should be paged

regularly during the day with the

relevant information to ensure

effective performance management

and to be able to reallocate

resources as necessary.

At West Midlands

Ambulance Service,

appropriate managers have

access to the Trust's CAD

system which holds details of

incidents that are either

current or have been managed

by the Trust.

It is recommended that the pager

message has the following

information:

current performance for

Category A;

current activation standard;

field resource total;

number of all 999 calls;

number of red calls;

percentage of red calls.

The pager message should be sent

to all managers at regular intervals

e.g. Monday to Friday at 0900

hours, 1200 hours and 1600 hours.

Managers should utilise this data to

modify resources to improve

performance. Some services operate

a special measures procedure (see

next page).

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

The Trust have introduced

the 'SmarTerm' software

system which allows

password protected access

to real and post time data,

thereby allowing managers

to actively interrogate the

system in a number of ways

to ensure that responses and

clinical care are managed

appropriately. Such

interrogations may include

National Charter Standards

performance on a cumulative

and individual case basis, as

well as mobilisation, call

assignment, hospital turn

around times etc.

The availability of such

information has proved vital

for enabling Trust managers

at all levels to proactively

manage issues and delays

as they arise.

Special Measures

The decision to implement Special

Measures will take into account the

following elements:

Time of day.

Number of Category A calls.

Number of Category A calls

missed.

Staff hours lost/gained.

Number of outstanding urgents.

1. Once a decision has been

made to implement special

measures, the control room

must be informed immediately

and all staff and managers

paged accordingly.

2. Ensure that all managers are

paged with the message

Special Measures

Implemented giving details of

current performance status.

3. On receipt of a Special Meas

ures Implemented pager message,

all officers and managers are to

clear their diaries and report their

availability for operational duties

to the control room.

4. The Fleet Department is to

immediately establish which

vehicles can be released from

workshops for operational use

and inform communications

centre and general managers.

5. The Training Department is to

establish if any personnel can be

made available for operational

duty and inform the control

room accordingly.

6. Senior Managers should ensure

that all resource information is

recorded adequately and that all

managers take appropriate action

upon receipt of Special Measures

Implemented notification.

7. The decision to stand down

from Special Measures will be

made by the Senior Managers /

Directors.

8. Once the decision has been

made to stand down, the duty

control room officer will ensure

that all managers are paged and

that relevant personnel are

informed.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 19

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Roles

There is some good practice

guidance on roles and

responsibilities in control rooms in

various trusts and it is advisable that

those wishing to review their own

practices make contact with other

services.

Managing Rotas

The contacts from GMAS and Kent

listed in Appendix 3 of this

document, would be happy to

discuss their arrangements with you.

Leadership and Communication

There has been much research and

evidence to indicate that effective

leadership and communication are

crucial tools that are necessary to

bring about and manage change

and sustain improvements. This is

also true within the ambulance

service, as the example below

suggests. However, IPAS would not

prescribe a particular leadership style

or communications approach but

leave it to individuals and

organisations to determine a style

and approach that is appropriate to

their circumstances. IPAS can be

contacted for reference points or

training and development advice by

those wishing to explore this area

further.

20

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Good Practice Example:

To engender accountability, responsibility and a sense of

belonging for individuals, GMAS introduced a team structure

for Control and Operations staff. Each of the 4 teams

consists of a Control Manager, Resource Manager, Supervisor

and 6 Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD) Call Takers and 10

EMD Dispatchers. These 24-hour teams work the same shift

patterns and there are also alternating teams and additional

shift staff to help cover Thursday, Friday and Saturday night

peak demand times.

Each team is given key performance indicators (that include the

Category A, B, C and GP Urgent targets) and the Control

Manager for each team is accountable for the performance of

the team and the individual team members.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Advantages, for example, better

leave management and effective

matching of resource to demand,

can be gained through central

management of rotas. It is

recommended that local self

rostering between crews be applied

to allow adjustments after the

central rota is set. Overlap for shift

starts and ends should be factored in

to allow of cleaning and restocking

of vehicles unless you are following

the model of skill mixing on these

tasks.

Planned Leave

For example annual leave, study

leave etc.

There are various factors that can

adversely affect unit hour resource

availability and need to be

considered when planning and

managing rotas:

In conjunction with the Human

Resources Department, unplanned

leave should be analysed and

planned into the demand analysis.

The average relief rate is 33% of the

whole time equivalent in order to

provide an effective service for

annual, sick and study leave.

Seasonal Demand

Demand analysis will highlight

seasonal demand which will affect

all services, for example increases

during December and January.

However, depending on geography,

demand can significantly alter during

summer months due to:

The weather (the Met Office can

predict future demand in

healthcare based on their weather

forecasts).

Epidemic illnesses.

Large scale public events.

School or public holidays

(impending changes to educational

holidays will influence demand).

It is advisable to calculate the

maximum hours allocated to

planned leave per location, per

week, and not to allow actual leave

to exceed this calculation. Advance

plans should be made for the

appropriate number of staff to be

off per week during the year.

Unplanned Leave

For example sickness.

Staff sickness levels need to be

monitored and proactively managed

and reported through performance

reports, especially if levels are above

4%. Systems, such as the Bradford

Index or other suitable system,

should be used for monitoring and

analysis. Further guidance can be

found in Section 5 of the IPAS

document Human Resources

Information for Ambulance Services

To assist in the delivery and

measurement of your HR Services

from IWL to CNST published in

October 2004 (see Appendix 4 of

this document for further

information).

Part-time Staff, Bank Staff,

Annualised Hours

Huge advantages can be gained

from the lateral use of part time and

bank staff and annualised hours

during peak demand hours and to

cover planned and unplanned leave.

Job share practices also allow for

flexibility. These staff groups should

be recruited and trained on the basis

that they will be used e.g.

recruitment adverts should state that

they will be used during periods of

high demand only.

Appraisals and Training

Uninterrupted time should be

secured to enable regular appraisals

to be conducted and appropriate

training to be provided. Appraisal

should be used to discuss an

individuals performance and analysis

on their response rates etc should be

fed back.

Vehicle Maintenance

This should be planned during times

when demand is low, for example

weekday evenings after 11pm, and

should be co-ordinated and agreed

with the Fleet Department.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 21

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Appendix 1 - National Standards, Local Action:

Health and Social Care Standards and Planning

Framework 2005/06-2007/08

Existing commitments

to be maintained

Commitments due to be achieved

before March 2005

Reduce to four hours the

maximum wait in A&E from arrival

to admission, transfer or

discharge.

Guaranteed access to a primary

care professional within 24 hours

and to a primary care doctor

within 48 hours.

All ambulance trusts to respond to

75% of Category A calls within 8

minutes.*

All ambulance trusts to respond to

95% of Category A calls within 14

(urban)/19(rural) minutes.*

All ambulance trusts to respond to

95% of Category B calls within 14

(urban)/19(rural) minutes.*

Maintain a two-week maximum

wait from urgent GP referral to

first outpatient appointment for all

urgent suspected cancer referrals.

Maintain a maximum two-week

wait standard for Rapid Access

Chest Pain Clinics.

3 month maximum wait for

revascularisation by March 2005.

From April 2002 all patients who

have operations cancelled for nonclinical reasons to be offered

another binding date within 28

days or fund the patients

treatment at the time and hospital

of the patients choice.

Commitments due to be achieved

after March 2005

Improve life outcomes of adults

and children with mental health

problems by ensuring that all

patients who need them have

access to crisis services by 2005,

and a comprehensive Child and

Adolescent Mental Health service

by 2006.

Ensure that by the end of 2005

every hospital appointment will be

booked for the convenience of the

patient, making it easier for

patients and their GPs to choose

the hospital and consultant that

best meets their needs. By

December 2005, patients will be

able to choose from at least four

to five different health care

providers for planned hospital

care, paid for by the NHS.

Ensure a maximum waiting time of

one month from diagnosis to

treatment for all cancers by

December 2005.

Achieve a maximum waiting time

of two months from urgent

referral to treatment for all cancers

by December 2005.

800,000 smokers from all groups

successfully quitting at the 4-week

stage by 2006.

*Note: The underlying definitions for

these standards and the split between

rural and urban services will be

clarified later in 2004, as part of the

current ambulance review.

22

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

In primary care, update practicebased registers so that patients

with CHD and diabetes continue

to receive appropriate advice and

treatment in line with NSF

standards and, by March 2006,

ensure practice-based registers and

systematic treatment regimes,

including appropriate advice on

diet, physical activity and smoking,

also cover the majority of patients

at high risk of CHD, particularly

those with hypertension, diabetes

and a BMI greater than 30.

A minimum of 80% of people

with diabetes to be offered

screening for the early detection

(and treatment if needed) of

diabetic retinopathy by 2006, and

100% by 2007.

Achieve a maximum wait of 3

months for an outpatient

appointment by December 2005.

Achieve a maximum wait of 6

months for inpatients by

December 2005.

Deliver a ten percentage point

increase per year in the proportion

of people suffering from a heart

attack who receive thrombolysis

within 60 minutes of calling for

professional help.

Delayed transfers of care to reduce

to a minimal level by 2006.

Appendix 2 - Definitions for Completion of KA34

Emergency calls and patient

journeys:

Category A emergency calls are

those classified as immediately lifethreatening. Urgent and nonurgent transport requests may be

classified as Category A calls after

interrogation and the agreement of

the caller. Where there have been

multiple calls to a single incident,

only one call should be recorded

(except in line 01 where all

emergency calls are to be counted).

Category B &C emergency calls are

those classified as being other than

immediately life-threatening. Urgent

and non-urgent transport requests

may be classified as Category B or C

calls after interrogation and the

agreement of the caller. Where there

have been multiple calls to a single

incident, only one call should be

recorded (except in line 01 where all

calls are to be counted).

Patient journeys: each patient

conveyed is counted as an individual

patient journey.

Urgent patient journeys are those

resulting from an urgent transport

request. An urgent transport request

is defined as a request when a

definite time limit is imposed such

that the vehicle and crew must be

despatched quickly, although not

necessarily immediately, to collect a

patient, perhaps seriously ill, on the

advice of a doctor for admission to

hospital.

Exclude urgent transfer requests

which, after interrogation and the

agreement of the caller, are treated

as Category A, B or C emergency

calls. "High dependency" calls

should be included only if they

satisfy the definition of an "Urgent"

Patient Journey.

Non -urgent patient journeys exclude non-urgent transfer

requests, which after interrogation

and the agreement of the caller are

treated as Category A, B or C

emergency calls or Urgent Patient

Journeys

Timing of response times

An Association of Ambulance

Services (ASA) publication defines

"clock starts" as the time

according to the current Department

of Health guidelines ie after

confirmation of the location and

chief complaint. For AMPDS users

this will be when the response to

Question 13 is entered or when

ProQA protocol is commenced. For

CBD users this will be when the

chief complaint is entered.

For all users there will be automatic

clock start 60 seconds after the first

key stroke if the points defined

above have not yet been reached.

(Reference: ASA A report into the

measurement of emergency

response times and 999 call

categorisation, August 2002)

The "clock stops" when the

emergency response vehicle arrives

at the scene of the incident.

Urban/rural services

Urban services are those where the

population density of the area

covered was greater than 2.5

persons per acre in 1991.Rural

services are those where the

population density of the area

covered was less than 2.5 persons

an acre in 1991.The following areas

are classified as urban:

London, Avon, Merseyside, South

Yorkshire, West Midlands, West

Yorkshire, Greater Manchester,

Surrey.

Source of info:

AMBULANCE SERVICES: GUIDANCE

NOTES FOR COMPLETION OF KA34,

2002-03

Pg17 of Ambulance Services,

England: 2002-03 (National Statistics

prepared by Government Statistical

Service)

NB: The underlying definitions for

the above targets and the split

between rural and urban services

will be clarified as part of the current

ambulance review.

A response within eight minutes

means eight minutes zero

seconds or less. Similarly, 14

minutes means 14 minutes 0

seconds and 19 minutes mean 19

minutes 0 seconds or less.

Emergency response

An emergency response may be by:

an emergency ambulance: or a rapid

response vehicle equipped with a

defibrillator to provide treatment at

the scene; or an approved first

responder equipped with a

defibrillator, despatched by and

accountable to the ambulance

service.

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 23

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Appendix 3 - Table of Contributors

Appendix 4 - Definitions and Useful Information

This document has been written with the kind contributions of:

Control Room - this is terminology used

in this document to mean communication

centre also

Ray Creen

Director of Patient Services, Kent Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Anna Garrett

Ambulance Policy, Department of Health

Keith Prior

General Manager, Paramedic Emergency Control,

Greater Manchester Ambulance Service NHS Trust keith.prior@gmas.nhs.uk

Dom Robertson

Deputy Director of Operations, Hereford and Worcester Ambulance Service NHS Trust

dominic.robertson@hwas-tr.wmids.nhs.uk

Manjit Smith

Business Manager, IPAS

Julia R A Taylor

National Programme Director, IPAS

Phoebe White

Support Worker / PA, IPAS

IPAS would also like to thank the following for their contributions:

Anthony Marsh

Chief Executive, Essex Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Barry Johns

Chief Executive, West Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Anne Walker

Chief Executive, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Simon Featherstone

Chief Executive, North East Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Gary Butson

Director of Operations, Surrey Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Andy Cashman

Director of Operations, Sussex Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Mike Cassidy

Director of Operations, Hampshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Steve Pryor

Director of Operations, WestCountry Ambulance Service NHS Trust

24

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

Dynamic Cover Plan - Where despatch

points are allocated

Despatch Point - A point (which is worked

out by data analysis) from which an

ambulance can be deployed to an incident

within the target time. This point is not

only the ambulance station, but can be the

side of a road, GP surgery/healthcare

centre, other emergency service partners (ie

Police or Fire station). Some fast food

outlets may let ambulances park on their

premises free of charge and may even

provide refreshments. The added benefit is

that most of these premises are in high

priority areas.

High Priority Area - An area, which

through demand analysis, has indicated a

high density of Category A incidents at

specific periods of time.

AMPDS - Advanced Medical Priority

Despatch System

CBD - Criteria Based Despatch

PTS - Patient Transport Service

ACA - Ambulance Care Assistant

Intermediate Tier This has different

definitions at different Trusts i.e. at Kent

this called Special Transport Service

resourced by a Technician and ACA, and at

Hereford and Worcester this is called High

Dependency Service resourced by an ACA

with additional skills.

National Standards, Local Action:

Health and Social Care Standards and

Planning Framework 2005/06-2007/08 sets out the framework NHS organisations

and social service authorities are to use in

planning for the next three financial years

and the standards which all organisations

should achieve in delivering NHS care. The

document can be found of the Department

of Health website at:

www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAnd

Statistics/Publications/Publications

PolicyAndGuidance/fs/en

Delivering the NHS Plan Strengthening

Accountability: Appropriate Use of

Ambulance Services (28th June 2002)

Can be found at the Department of Health

website at

www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/01/37/27/040

13727.pdf

Good Practice Guide on Human

Resource for Ambulance Services

To assist in the delivery and

measurement of your HR Services from

IWL to CNST (2004) - A best practice

document developed by IPAS which

summarises the key requirements of HR

standards and provides a checklist for all

actions required. Available on the IPAS

website at www.modern.nhs.uk/ambulance

Improving Working Lives -The Improving

Working Lives Standard (IWL) sets out a

model of human resources practice. NHS

employers will be kite-marked against their

ability to show that they are providing a

better deal for NHS staff in their working

lives. For guidance on how to apply the

practice, refer to the Human Resources

Guidelines for Ambulance Services.

The following documents/toolkits are also

available:

NHS Childcare Toolkit III: The new

dimension Published by the

Department of Health & Daycare Trust,

July 2004.

Available at the Department of Health

website

www.dh.gsi.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/

HumanResourcesAndTraining/Model

Employer/ImprovingWorkingLives/fs/en

Or: www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04

/08/42/65/04084265.pdf

Improving Working Lives for

Ambulance Staff For a copy of the

document email doh@prolog.uk.com

quoting reference 40206 or at the

Department of Health website at

www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAnd

Statistics/Publications/PubliationsPolicy

AndGuidance/fs/en

Or view at

www.doh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/

46/16/04084616.pdf

Improving Working Lives: Practice

Plus National Audit Instrument

Hard copies available from the NHS

Response Line on 08701 555 455 or

via the Department of Health

website at

www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAnd

Statistics/Publications/PubliationsPolicy

AndGuidance/fs/en

Or view at

www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/44/

63/04084463.pdf

Health and Safety Legislation Guidance around ensuring the health and

safety legislation is implemented can be

found in the Human Resources Guidelines

for Ambulance Services, or visit the

Department of Health website

www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/

OrganisationPolicy/HealthAndSafety/fs/en

Controls Assurance - The NHS Controls

Assurance project requires NHS boards to

give assurances that their organisations are

doing their reasonable best to protect

patients, staff, visitors and other

stakeholders against risks of all kinds.

Consult the Human Resources Guidelines

for Ambulance Services for guidance on

implementing the assurances or visit the

Department of Health website

www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/HealthAn

dSocialCareTopics/ControlsAssurance/fs/en

Clinical Governance - Clinical governance

is the system through which NHS

organisations are accountable for

continuously improving the quality of their

services and safeguarding high standards of

care, by creating an environment in which

clinical excellence will flourish. The Human

Resources Guidelines for Ambulance

Services are useful in ensuring a suitable

system is in place. The Department of

Health website also provides useful

information

www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/Health

AndSocialCareTopics/ClinicalGovernance/fs/

en

Driving Change Good Practice

Guidelines for PCTs on Commissioning

Arrangements for Emergency

Ambulance and Non Emergency Patient

Transport Services - Available on the IPAS

website at www.modern.nhs.uk/ambulance

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services 25

Best Practice Guidelines on Ambulance Operations Management

This document is also available on

the Improvement Partnership for

Ambulance Services (IPAS) website

at www.modern.nhs.uk/ambulance

26

Improvement Partnership for Ambulance Services

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Patient Transport PolicyDocument15 paginiPatient Transport Policydrwaheedhegazy100% (2)

- QPS Sample GuidelinesDocument23 paginiQPS Sample GuidelinesSafiqulatif AbdillahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nurse Bob's MICU/CCU Survival Guide Critical Care Concepts General Nursing Requirements of The Intensive Care PatientDocument7 paginiNurse Bob's MICU/CCU Survival Guide Critical Care Concepts General Nursing Requirements of The Intensive Care Patientlil' princessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Operating ProceduresDocument13 paginiStandard Operating Proceduresmeow meowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lsti Emt B ManualDocument190 paginiLsti Emt B ManualPonzidiane123Încă nu există evaluări

- Policy For Ambulance ServicesDocument11 paginiPolicy For Ambulance Servicesummuawisy0% (1)

- Policies and Procedures For Ambulance ServiceDocument3 paginiPolicies and Procedures For Ambulance ServiceLymberth Benalla100% (1)

- BLS Ambulance Checklist New Standards 2019Document7 paginiBLS Ambulance Checklist New Standards 2019Gerard Alfelor100% (1)

- 8.1 Initial Assessment and Resuscitation Skill Station Guidance1 2010Document4 pagini8.1 Initial Assessment and Resuscitation Skill Station Guidance1 2010brianed231Încă nu există evaluări

- Preceptor EvaluationDocument2 paginiPreceptor Evaluationapi-380898658Încă nu există evaluări

- Improving Healthcare Through Advocacy: A Guide for the Health and Helping ProfessionsDe la EverandImproving Healthcare Through Advocacy: A Guide for the Health and Helping ProfessionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy For Community First Responders V3.0Document14 paginiPolicy For Community First Responders V3.0f4phixerukÎncă nu există evaluări

- prehospital-EMS-COVID-19-recommendations - 4.4Document19 paginiprehospital-EMS-COVID-19-recommendations - 4.4MEONEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peer Review Process: Official Reprint From Uptodate ©2018 Uptodate, Inc. And/Or Its Affiliates. All Rights ReservedDocument18 paginiPeer Review Process: Official Reprint From Uptodate ©2018 Uptodate, Inc. And/Or Its Affiliates. All Rights ReservedMiguel RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Practice in AmbulanceDocument4 paginiClinical Practice in Ambulancengurah_wardanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Penn Medical Emergency Response Team ProtocolsDocument70 paginiPenn Medical Emergency Response Team ProtocolsPennMERTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategy For A National EMS Culture of Safety 10-03-13Document98 paginiStrategy For A National EMS Culture of Safety 10-03-13Em SyArifuddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPR Team DynamicsDocument31 paginiCPR Team Dynamicsapi-205902640Încă nu există evaluări

- Crowd Management PolicyDocument3 paginiCrowd Management PolicyAffan sami rayeenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ambulance OperationsDocument36 paginiAmbulance OperationsUliuliauliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ambulance Contigency PlanDocument1 paginăAmbulance Contigency Planrhu lalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Department Director ResponsibilitiesDocument6 paginiEmergency Department Director ResponsibilitiesLuis NavarreteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Medical Response - Instructor Trainer Bridge InstructionsDocument8 paginiEmergency Medical Response - Instructor Trainer Bridge Instructionsjohnnathan riveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Department PolicyDocument18 paginiEmergency Department PolicyKumar Gavali Suryanarayana100% (1)

- Toledo Code Blue PolicyDocument4 paginiToledo Code Blue PolicySt SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accident and Emergency DepartmentDocument9 paginiAccident and Emergency Departmentshah007zaadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inter Hospital Transfer SopDocument2 paginiInter Hospital Transfer SopNATARAJAN RAJENDRANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intensive Care UnitDocument12 paginiIntensive Care UnitAnt OnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accident and EmergenciesDocument5 paginiAccident and EmergenciesArnel AlmutiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ambulance Response Protocol DraftDocument3 paginiAmbulance Response Protocol DraftCommand CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Medical ServiceDocument30 paginiEmergency Medical ServiceKeLvin AngeLes100% (1)

- Hospital Emergency Codes FinalDocument35 paginiHospital Emergency Codes FinalaldibaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scheduling of Patients For SurgeryDocument7 paginiScheduling of Patients For SurgeryAllein Antonio-GeganteÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCM Participant's ManualDocument144 paginiMCM Participant's ManualRex Lagunzad Flores100% (1)

- Policies and Procedures On Disposition of Dead Bodies With Dangerous CDDocument19 paginiPolicies and Procedures On Disposition of Dead Bodies With Dangerous CDsurigao doctors'100% (2)

- Internship Logbook 2nd Edition 1436 MaleDocument15 paginiInternship Logbook 2nd Edition 1436 MaleJESEE GITAUÎncă nu există evaluări

- Procedure Manual HospitalDocument196 paginiProcedure Manual HospitalMarian StrihaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPR Critical SkillsDocument2 paginiCPR Critical SkillsErickson TiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short Term Training Curriculum Handbook - EMT-B - 1 June 2017 - 1Document48 paginiShort Term Training Curriculum Handbook - EMT-B - 1 June 2017 - 1navneetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hospital Emergency Operations Plan TemplateDocument53 paginiHospital Emergency Operations Plan TemplateNicholaiCabadduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ambulance ManualDocument6 paginiAmbulance ManualSumit SardanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Department DesignDocument32 paginiEmergency Department DesignVivek Patwardhan100% (2)

- Medical Incident CommandDocument71 paginiMedical Incident CommandPaulhotvw67100% (3)

- Code Blue EvaluationDocument1 paginăCode Blue EvaluationJessica Garlets0% (1)

- Educational Catalog 2015 WebDocument20 paginiEducational Catalog 2015 WebFranciscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contingency Plan in Case of Vehicle BreakdownDocument1 paginăContingency Plan in Case of Vehicle BreakdownDessaryl ElgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preoperative Assessment PolicyDocument10 paginiPreoperative Assessment PolicymandayogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Part 1 Multiple ChoiceDocument4 paginiChapter 1 Part 1 Multiple ChoiceArlanosaurusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Er ManualDocument27 paginiEr ManualQuality Manager100% (2)

- ProtocolsDocument153 paginiProtocolsnutrientz100% (1)

- Orientation Booklet For Emergency DepartmentDocument10 paginiOrientation Booklet For Emergency Departmentshahidchaudhary100% (1)

- Ambulance Best Practice Report EnglishDocument23 paginiAmbulance Best Practice Report EnglishYasir RazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Preparedness: OrientationDocument32 paginiEmergency Preparedness: OrientationElizabella Henrietta TanaquilÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHECC Field Guide 2011Document125 paginiPHECC Field Guide 2011Michael B. San JuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Missing Patients ProcedureDocument16 paginiMissing Patients ProcedureAgnieszka WaligóraÎncă nu există evaluări

- IcuDocument8 paginiIcuBikul Nayar100% (1)

- Ambulance Inspection Checklist-7-2-08 - The Word Draft RemovedDocument5 paginiAmbulance Inspection Checklist-7-2-08 - The Word Draft RemovedAnonymous GsCkcq8fÎncă nu există evaluări

- 31-Nursing Assessment For Out Patient DepartmentDocument2 pagini31-Nursing Assessment For Out Patient DepartmentakositabonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Checklist - HospitalDocument21 paginiFinal Checklist - HospitalZandra Lyn Alunday100% (1)

- Hospital Emergency Response Teams: Triage for Optimal Disaster ResponseDe la EverandHospital Emergency Response Teams: Triage for Optimal Disaster ResponseÎncă nu există evaluări