Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Phys221 Research Project Guidelines

Încărcat de

Truc TaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Phys221 Research Project Guidelines

Încărcat de

Truc TaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Research Project Guidelines

PHYS &221

RESEARCH PROJECT GUIDELINES

I. WHY A RESEARCH PROJECT?

In short, because it represents a genuine research activity. Your physics research project is an opportunity to

exercise your creativity, interests, critical thinking, ability to make contacts, procure resources and information, and

ultimately to provide you with increased opportunity, including a nice, polished example of your work that you can

show to college admissions boards and/or future employers that will set you apart from your competition.

II. TYPES OF PROJECTS: EXPERIMENTAL vs. THEORETICAL

Physics project types fall into two basic classes: Experimental or Theoretical1

Experimental

Experimental projects are very hands-on, involving setting up, and in many cases, construction of your

own experimental equipment. You will be able to borrow whatever equipment we have available for your

project, and sometimes you might have to purchase some miscellaneous (but inexpensive) items, or build

them from scraps you hunt-down. Experimental projects tend to be very straightforward to do once youve

come up with your idea, and they also tend to be self-running in the sense that once you get started, the

ideas and results keep flowing-in quite naturally.

Theoretical

Theoretical projects tend to be much more difficult because (1) there is a much higher knowledge-base

required before most people are ready to carry out an original calculation, and (2) because of this, one

can easily fall into the trap of producing merely a scientific book-report a collection of other peoples

ideas with little or no original student input. Original student input does not necessarily mean an original,

earth-shattering discovery; rather it can be a calculation that is not necessarily original to others, but is

original to you; nevertheless, it must also be a calculation that isnt so common that it can simply be copied

from elsewhere. There have been a few very successful theoretical student research projects in the past, so

they are certainly do-able, and you are free to do one if thats what youre interested-in.

Keep in-mind that your physics research project will be something very different from a Book Report or a Research

Essay that you may be familiar with from some of your other classes. The skills that you have practiced in your

other writing-requirement classes will come in very handy for doing the background research, but in addition to that,

you will have to formulate your own research questions, design and construct your own experiments, collect and

analyze data, and form conclusions which are based on quantitative measurements and calculations. You will

actually have to do something, and then write about what youve done, rather than simply summarizing what some

other people have done.

III. LEVELS of PROJECTS

Both Experimental and Theoretical projects may be at different levels, depending on the interests, level of challenge,

and goals sought by the student, for example:

One-Quarter Projects

Minimal, course-requirement-fulfilling projects are those that can be finished in one quarter and reflect

about four weeks worth of work, with consideration given of your regular course load, background

research, experimental time, equipment procurement/construction time, and writing time.

Multi-Quarter Projects

Most researchers spend all of their time doing either Experiment or Theory because each in itself requires such

substantial and different special knowledge and skills that it is practically impossible to do both. Every now and

then, however, Nature will provide us with someone like Enrico Fermi, who was capable of doing both equally-well.

Page 1 of 6

Research Project Guidelines

PHYS &221

Oftentimes, a student will shoot for a one-quarter project and then find that they want to continue building

on the same project in subsequent quarters. Likewise, a student might start-off interested in topics that will

necessarily take more than one-quarter to complete. With these more-ambitious projects, getting to an endresult in one quarter is not always possible, but that is fine - simply demonstrating the same kind of

progress outlined in the minimal one-quarter requirements towards the eventual goal is sufficient. Most

one-quarter projects tend to turn into multi-quarter projects quite naturally as the student progresses.

IV. RESEARCH POSTER REQUIREMENTS

A. TYPESETTING and LAYOUT

There are no tight rules here. Your typeset must be big enough and clear enough to read from 3-5

ft away (imagine a group of about 4 people all trying to read your poster at the same time).

Posters are a visual product, so you want images to dominate, but use your text to explain the

images and insert the real content.

Make sure that your poster has a natural flow, so viewers are guided through the information in a

meaningful way.

Finally, make sure that your poster is both attractive and professional looking! Use colors, fonts,

and decorations to attract viewers, but not distract viewers.

C. USE of EXTERNAL CITATIONS and RESOURCES

Your research project must be your own, original work, written in your own words. Nevertheless,

research papers and posters necessarily include references to the work of others. All referenced

work must be properly cited, and any sentences or paragraphs which are directly taken from

external resources must be properly cited and attributed to the original authors.

Sentences and paragraphs which are directly taken from other works must appear in blockquotations, and under no circumstances may the word-count of any poster (or future paper) exceed

10% directly-quoted or paraphrased material.

Please see Section VI: Formatting of Citations and References below for more information about

citations and references.

D. FORMATTING AND SECTIONS

The below are general guidelines for the information to include in your poster. In the back of our

lab there are some example posters to make the formatting described below a little more clear.

ABSTRACT

An abstract is a really brief summary of your poster. This should include

(1) A brief description about the specific physical phenomenon you studied.

(2) A statement of your testable hypotheses.

(3) A brief description of your experiments.

(4) Whether your experimental data supports or rejects your hypotheses.

(5) A brief summary of your conclusions.

BODY

Introduction

The purpose of this section is to provide readers who may not be experts in your specific

topic with sufficient background information to be able to understand what your poster is

about.

Page 2 of 6

Research Project Guidelines

PHYS &221

Experiment

Materials and Apparatus

This purpose of this section is to provide other researchers with sufficient information

about the materials and apparatus that you used that they would be able to independently

reproduce your experiment. A picture is worth a 1000 words here!

If you are using apparatus manufactured by a third party, you should include enough

information about the apparatus, such as names, descriptions, and model numbers that

another researcher would be able use the same or similar apparatus.

If you are constructing your own apparatus, you should provide sufficient materials

descriptions, instructions, diagrams, and photographs that other researchers would be able

to independently construct and use the same apparatus.

Procedure

The purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to follow the same procedures

that you did in order to independently verify (or refute) your findings.

Data and Analysis

This section should contain clearly-labeled data tables, charts, and graphs, and your data analysis

and error analysis. When planning your experiment, you should think carefully about how much

and what kind of data you will need in order to be able to accept or reject your hypothesis.

Conclusions

This is where you will conclude that you must either accept or reject your hypothesis based on

your experimental findings. Your conclusion needs to be supported by your experimental

evidence.

Future Work

This is where you make suggestions for experimental improvements and further work related to

your experiment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is where you thank other people who were helpful with your research. If, for example, you

got help with your project from somebody in another department or another at EdCC, someone in

the community, or at another institution you should acknowledge them here.

REFERENCES

This is where you list all of your references cited on your poster.

V. PRESENTATION REQUIREMENTS

FORMAT

You will participate in three (or more) poster sessions during our final class meeting. During one of these

sessions you will guide viewers through your poster with a short (~3 minute) presentation, and then be

available for questions. As people mill about during the poster session, you may make your presentation 3

or more times. During the other 2 (or more) sessions, you will be a viewer, learning about your classmates

projects, reading posters, and asking questions. Participation in the poster session will count for 15% of

your poster grade.

Page 3 of 6

Research Project Guidelines

PHYS &221

VI. FORMATTING of CITATIONS and REFERENCES

A. The Big Idea

All scholarly fields share in the idea that information and work taken by an author from other authors

should be clearly attributed to the original authors. Information and work used by an author without

attribution to the original authors is called plagiarism.

Since the discovery of even a seemingly minor scientific fact or insight often has come only from a person

having invested their entire lifes work in it, plagiarism is considered to be a very serious transgression

among scientists. Even unintended plagiarism can result in permanent excommunication from ones

scientific community.

In practice, the accepted format for presenting these attributions depends not only on accepted norms of the

particular discipline, but also on the particular journals in which an author is seeking to be published.

Most, if not all, of you are already familiar with the MLA and APA citation formats used for research

papers in your English and other Humanities courses. The reason these citation formats are taught to you

is because they are the ones generally preferred by the people and professional journals in the Humanities.

For example, when the APA citation format prefers that your in-text citations cite external resources in

(Name, Year, Page) format. An in-text citation might be, for example:

In 1932, Jones was the first to discover that peanuts went well with chocolate, stating:

Hey, this chocolate goes really well with peanuts! (Jones, 1932, p.1539).

Then, in the References section of the poster, the reference for this citation would be given in (Name/Year)

format:

Jones, A. B. (1932). Peanuts enhance chocolate flavor. Peanut Psychology, 34, 1257-1794.

On the other hand, many Physics journals dont use either APA or MLA format, preferring instead a certain

minimalism on their in-text citations. The typical in-text citation appearing in Physics journals uses a

[Citation Number] format. For example, the same citation above would appear in the journal Physical

Review as:

In 1932, Jones was the first to discover that peanuts went well with chocolate [3].

Or

In 1932, Jones was the first to discover that peanuts went well with chocolate, stating Hey, this

chocolate goes really well with peanuts! [3]

Then, in the Reference section of the poster, the reference for this citation would be given in [Citation

Number] format:

[3] A.B. Jones, Peanut Psychology, 34 (1932).

Notice how the Physical Review style is much more minimalistic than the APA style. The in-text citation

appears as just [3], and the reference includes only the author, journal name, volume number and year.

Page 4 of 6

Research Project Guidelines

PHYS &221

Exactly how an article versus a book versus an internet references versus a phone conversation, ad

nauseum, should be formatted is determined solely by how a particular journal (or teacher) wants it

formatted. APA is very specific, Physical Review is very minimalistic, and other journals tend to be inbetween these two extremes. The only way to know these details is for them to be provided to you as a

required style. English teachers will often refer you to APA or MLA styles as their required style. (See

for example http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/section/2/10/ for APA and MLA styles, and see

http://forms.aps.org/author/styleguide.pdf for the Physical Review Style Guide.)

Regardless, what all citation formats have in-common are that they contain enough information for your

audience to be able to easily verify an attribute the sources you use. Both the APA and Physical Review

styles are the same in this regard.

B. Specific Citation and References Style for Your Research Poster (and future papers)

For the purposes of your poster, please use a [Citation Number] format like in the Physical Review style.

Give me an in-text number [N] for your citations and a corresponding numbered-entry in your References

section that is sufficient for another party to be able to independently verify your citations. You will

otherwise not be expected to become experts in all the details of Physical Review style.

C. The 10% Rule

If you take word-for-word material from another resource, you must (1) cite it in your text, (2) include the citation in

your references, and (3) put it in block-quotes. For example,

Jones indicated that she

observed unusual amplification of salivary responses among patients consuming peanut-doped

chocolate emulsions. [3]

On a word-count basis, your writing may consist of no more than 10% of this type of quoted material.

D. Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing means to say the same thing that someone else has said but in a slightly different way, using perhaps a

slightly different sentence structure and/or different words. For example, suppose that you use an internet reference

in your poster that reads:

Einstein revolutionized the way that early 20th-century physicists understood the nature of space and

time.

This statement is of course true, and because of its linguistic simplicity it would not be hard to imagine that several

authors over the past 100 years could have made exactly that same comment independently and originally. Such an

accident of sentence structure independently-made would of course not be plagiarism, but one would never, ever

want to be in a circumstance where someone else says I found exactly this same sentence published by Jones five

years ago. I think you plagiarized it!

If you really like the way the sentence is said, but you did not honestly think of the sentence yourself, feel free to use

it, but just cite it and put it in block-quotes.

A paraphrasing of the above sentence would be a variation on it such as

The way that 20th century physicists though about physics was changed dramatically by Einstein.

Was this sentence original and spontaneous, or did somebody just steal the former sentence and change the wording

around in and attempt to hide the fact that they stole it?

Page 5 of 6

Research Project Guidelines

PHYS &221

Again, its hard to tell for sentence structures that occur with high-probability such as the two above. It is on the

other hand very easy to tell for more complicated sentence structures that include less-than-common knowledge.

Deliberate honesty is always the guide to not accidentally falling into the abyss of plagiarism. Question yourself and

question how others may question you about your claims, and you will very comfortably never have to deal with

accusations of plagiarism.

Page 6 of 6

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Logo 3Document1 paginăLogo 3Truc TaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- We Have Successfully Recalibrated The Camera Connected To Your WindshieldDocument1 paginăWe Have Successfully Recalibrated The Camera Connected To Your WindshieldKelly BedonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workshop Practice Series 17 - Gears and Gear CuttingDocument138 paginiWorkshop Practice Series 17 - Gears and Gear CuttingSpyros DagklisÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- LinkagesDocument29 paginiLinkagesRubén GonzálezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Brief DescriptionDocument53 paginiBrief DescriptionTruc TaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Fanuc LATHE CNC Program Manual Gcodetraining 588Document104 paginiFanuc LATHE CNC Program Manual Gcodetraining 588DOBJAN75% (12)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- General Machinist HandbookDocument320 paginiGeneral Machinist HandbookHakuna Matata100% (7)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Fanuc LATHE CNC Program Manual Gcodetraining 588Document104 paginiFanuc LATHE CNC Program Manual Gcodetraining 588DOBJAN75% (12)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- 3d Printing TutorialDocument25 pagini3d Printing TutorialTruc Ta100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Hex - Holder: Solidworks Student License Academic Use OnlyDocument1 paginăHex - Holder: Solidworks Student License Academic Use OnlyTruc TaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elect Raining SchoolsDocument3 paginiElect Raining SchoolsTruc TaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Từ Nối Và Ví Dụ Minh Họa Dành Cho IELTS EssaysDocument6 paginiTừ Nối Và Ví Dụ Minh Họa Dành Cho IELTS EssaysTruc TaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADocument1 paginăATruc TaÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Merger of Bank of Karad Ltd. (BOK) With Bank of India (BOI)Document17 paginiMerger of Bank of Karad Ltd. (BOK) With Bank of India (BOI)Alexander DeckerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Analysis of The SPM QuestionsDocument5 paginiAnalysis of The SPM QuestionsHaslina ZakariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- 1.3 Digital Communication and AnalogueDocument6 pagini1.3 Digital Communication and AnaloguenvjnjÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Blind Chinese SoldiersDocument2 paginiBlind Chinese SoldiersSampolÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Mathematical InvestigationDocument1 paginăWhat Is Mathematical Investigationbj mandia100% (1)

- Eco 407Document4 paginiEco 407LUnweiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Individual Workweek Accomplishment ReportDocument16 paginiIndividual Workweek Accomplishment ReportRenalyn Zamora Andadi JimenezÎncă nu există evaluări

- AMBROSE PINTO-Caste - Discrimination - and - UNDocument3 paginiAMBROSE PINTO-Caste - Discrimination - and - UNKlv SwamyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- CabillanDocument12 paginiCabillanvivivioletteÎncă nu există evaluări

- P.E and Health: First Quarter - Week 1 Health-Related Fitness ComponentsDocument19 paginiP.E and Health: First Quarter - Week 1 Health-Related Fitness ComponentsNeil John ArmstrongÎncă nu există evaluări

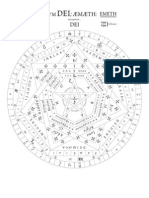

- John Dee - Sigillum Dei Aemeth or Seal of The Truth of God EnglishDocument2 paginiJohn Dee - Sigillum Dei Aemeth or Seal of The Truth of God Englishsatyr70286% (7)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- History RizalDocument6 paginiHistory RizalIrvin LevieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subculture of Football HooligansDocument9 paginiSubculture of Football HooligansCristi BerdeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIW Unit Plan - Ind. Tech ExampleDocument4 paginiAIW Unit Plan - Ind. Tech ExampleMary McDonnellÎncă nu există evaluări

- BTCTL 17Document5 paginiBTCTL 17Alvin BenaventeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- LESSON 6 Perfect TensesDocument4 paginiLESSON 6 Perfect TensesAULINO JÚLIOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operations Research Letters: Meichun Lin, Woonghee Tim Huh, Guohua WanDocument8 paginiOperations Research Letters: Meichun Lin, Woonghee Tim Huh, Guohua WanQuỳnh NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 101-160Document297 paginiChapter 101-160Dipankar BoruahÎncă nu există evaluări

- AL Applied Mathematics 1989 Paper1+2 (E)Document7 paginiAL Applied Mathematics 1989 Paper1+2 (E)eltytanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christian Education of Zendeling-Based at The Kalimantan Evangelical Church (GKE)Document16 paginiChristian Education of Zendeling-Based at The Kalimantan Evangelical Church (GKE)Editor IjrssÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7: Identifying and Understanding ConsumersDocument3 paginiChapter 7: Identifying and Understanding ConsumersDyla RafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 - Nature and Role of Science in SocietyDocument10 pagini02 - Nature and Role of Science in SocietyMarcos Jose AveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume - General Manager - Mohit - IIM BDocument3 paginiResume - General Manager - Mohit - IIM BBrexa ManagementÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Gift Shopper - Proposal - TemplateDocument67 paginiE-Gift Shopper - Proposal - TemplatetatsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 1 Course Objectives and OutlineDocument15 paginiWeek 1 Course Objectives and Outlinechrisbourque13Încă nu există evaluări

- Christiane Nord - Text Analysis in Translation (1991) PDFDocument280 paginiChristiane Nord - Text Analysis in Translation (1991) PDFDiana Polgar100% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- A Guide To Conducting A Systematic Literature Review ofDocument51 paginiA Guide To Conducting A Systematic Literature Review ofDarryl WallaceÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMPOSITION Analysis of A Jazz StandardDocument9 paginiCOMPOSITION Analysis of A Jazz StandardAndresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theater - The View ArticleDocument2 paginiTheater - The View ArticleRishi BhagatÎncă nu există evaluări

- La FolianotesDocument4 paginiLa Folianoteslamond4100% (1)