Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cannonball Adderley Issue

Încărcat de

Francesco GiambersioDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cannonball Adderley Issue

Încărcat de

Francesco GiambersioDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 9, no. 1, pp.

101-106 (Summer 2013)

Portrait of Cannonball: Cary Ginell's Walk Tall

Dustin Mallory

Walk Tall: The Music and Life of Julian Cannonball Adderley. By Cary Ginell.

Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Books, 2013. 190 pp. $18.99.

Very few jazz musicians can say that their band had a Top 20 single and a Top

20 album. Within that elite group of artists, only two men can state in the

same breath that they also performed on jazzs best-selling album of all time,

Kind of Blue. One is Miles Davis and the other is Julian Cannonball

Adderley. Cannonballs success in album sales is just one measure of his

achievements, albeit a tangible one. However, a casual stroll through the

practice rooms of any jazz school in the country or jazz club in a city will

aurally reveal the sheer volume of musicians that practice, perform, and revere

the vocabulary that poured from Cannonballs saxophone.

Yet, despite the respect that Cannonball has been accorded over the years,

both measureable and immeasurable, there is relatively little in the way of

published biographical information. With the exception of the occasional

feature in a periodical, an entry in The Encyclopedia of Jazz, a handful of

scholarly works, and a few publications geared toward theory or discography,1

Mr. Adderleys biography has gone largely unwritten. Furthermore, it can be

said definitively that there is nothing in the marketplace that even closely

resembles a comprehensive biography.

Cary Ginells Walk Tall is one of the first publications that sets theory,

analysis, and discography on the back burner in favor of history/biography.

The book is also the first in Hal Leonards Jazz Biography Series, which,

according to the publishers press release for Walk Tall, will be a set of concise

and accessible jazz biographies. This description is important to keep in

mind when evaluating Ginells book. It is a very short work that hits the

1

Chris Sheridan's Dis here: A Bio-Discography of Julian "Cannonball" Adderley, (Westport:

Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000) is a useful resource.

copyright by author

101

102

Journal of Jazz Studies

noteworthy signposts of Adderleys career without delving into academic

jargon, critical theory, or any other type of deep analysis. In fact, Chapter 1,

Cannibal, details Cannonballs life from birth to age twenty-seven (19281955) in just eight pages! Rather, Ginell, known primarily for his work as a

folklorist, radio broadcaster, journalist, and author of books on American

Roots music, provides a very crisp and conventional form of biography. He

succinctly states his perspective of Adderleys career in his introduction:

What Cannonball Adderley did was make jazz accessible to the average

persons ears. Previously, jazz was an in-group genre. You had to get it

from the inside out. With Adderley, you didnt have to understand

complex chord progressions, modal scales, or arcane musical references. All

you had to do was dig the groove (xv).

This statement reveals the lens through which Ginell views his subjects

story.

Nevertheless, Walk Tall contains some new information that could be

appealing to the layperson and researcher/academic alike., For example, Ginell

provides some family history from census documents as well as the familys

multi-generational relationship with Florida A&M University. Although some

of this information has been public before, Ginells book is the first widely

published source to include it.2 The author also provides an insert with rare

photographs and copies of membership cards that Cannonball carried in his

wallet, including his National Education Association and Broward County

Teacher Association cards. Also included in the chapters titled The New

Bird and Cannonball Takes Charge (Chapters 3 and 7), are brief

reconstructions of Cannonballs touring history. Ginell even takes time to align

the events chronologically with Cannonballs teaching engagements and

recording sessions:

For the remainder of 1955 Cannonball taught school during the daytime;

at night he assembled a band that played six nights a week at Porkys, a

local Fort Lauderdale nightclub. The Porkys gig lasted from September

2

Gig Brown's Know What I Mean: The Life and Music of Julian Cannonball Adderley (Rutgers

University, 1999) and Ricky Alonzo's Julian "Cannonball" Adderley: Selected Highlights of His

Life and Music (Florida State University, 2001) are two dissertations that predate Ginell's

publication and also make for excellent further reading.

Dustin Mallory / Ginell's Walk Tall

103

27, 1955, until the end of January 1956; the only break came when Bob

Shad flew Cannonball to New York to participate in Sarah Vaughns

inaugural session for EmArcy (18).

This historical retracing of Cannonballs life makes up the crux of Ginells

book. Other substantial details include well-known recording sessions,

wedding information, and events surrounding Cannonballs final days.

Another significant contribution are some new interviews, most

noteworthy those with Cannonballs widow, Olga Adderley Chandler. Some of

the details she expounds upon may seem mundane to some readers, but they

provide some insights into the character and personal life of the Adderleys. For

example, Olga stated: After we got married, Miles offered us an apartment in

his townhouse. We lived way out in Queens and Julian did not want to live in

town, and as much as he admired Miles, he did not want to be part of that

scene (95). Olga also revealed much about Cannonballs struggle with his

health problems: Julians weight certainly had a lot to do with his diabetes. He

never seriously tried losing weight but would go on minor diets and lose ten

pounds. But then hed get away from me and go out on the road and Id find

candy bars in his suitcase when he came home (97). Olga also cleared the air

about what had been known as Cannonballs nervous breakdown and near

institutionalization in 1963:

He was under a lot of stress because of touring and had been having

trouble with his teeth and embouchure. We were in Philadelphia and

apparently he and Nat were opening at this club and had an argument and

some people called me and said that Julian was crying and couldnt stop

He was out of it for quite a while and I had to beg Dr. Leffall not to

put him into an institution. While he was asleep I called my internist,

who taught at NYU, Dr. Herbert Chasis Dr. Chasis obtained his

records, so thats how I found out that he had had a minor stroke, (101102).

The only unfortunate thing about Ginells interview material is that there is

not more of it. While the concise nature of the publication leaves little room

for additional interview material, there is no such thing as too many research

interviews to inform a biography. By the authors own admission he only

104

Journal of Jazz Studies

conducted interviews with five people who were close to Adderley for the

book. This fact has created some critical backlash.3

Ginell does not attempt in any way to be musically analytical in Walk Tall,

resulting in few musical insights. He does, however, sprinkle in a few details

for musicians like the following: The set included the ironically titled With

Apologies to Oscar (based on the chord changes to Sweet Georgia Brown)

(12). Ginells musical descriptions do get sticky in some places though. One

instance is when he proposes that Miles Davis wanted to emphasize modal

patterns, which are based on only the white keys of the piano, rather than the

traditional Western scale system, (30). Most musicians would find this

definition puzzling, but, fortunately, the book has very few of these musical

missteps.

In the chapter called Country Preacher, Ginell describes the arc of

change that marked the period 1968-1970. These years are known for

significant social stresses in the country as well as in jazz , and Cannonball was

certainly affected by them. Ginell also goes to great lengths to discuss

Cannonballs contributions as an educator in this chapter. He details

Cannonballs two-day lecture/seminar programs that he conducted at colleges

throughout the country in 1968 and 1969. Ginell outlines the curricular

framework of an Adderley clinic and how each member of the band was

expected to contribute:

Each was given a different topic to research and would then be asked to

conduct individual seminars at the schools. Roy McCurdy, who studied

percussion at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York,

gave lectures on African instruments and rhythm. Joe Zawinul, a

graduate of the Vienna Conservatory, discussed the differences between

European and African musical styles (136).

Ginell continues the chapter with a description of the Quintets college

performances and a recording session with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The

chapter ends with an account of Joe Zawinuls departure from the band.

Regrettably, Ginell makes a false claim in his description of Zawinuls

departure, stating: The seeds of it were most likely planted during Miles

3

See Lee Mergners book review: Lee Mergner, Walk Tall: The Music and Life of Julian

Cannonball Adderley, Jazz Times, August 2013, 70.

Dustin Mallory / Ginell's Walk Tall

105

Davis Bitches Brew sessions in 1968, when Zawinul first met Shorter and

began talking about their common aspirations (140). First, the Bitches Brew

(Columbia) sessions took place in 1969, not 1968. Second, Shorter and

Zawinul had played together and known each other for several years. Both

men were part of the Maynard Ferguson Orchestra which performed live at

the Newport Jazz Festival in 1959 (which was incidentally Shorters first issued

recording) a full decade before the Bitches Brew sessions.

The most fascinating and controversial aspect of the book is probably

Ginells canonization of Cannonballs recordings. One of the most difficult

aspects of writing a concise history of such a prolific musician is deciding

which music to talk about and which will have to be excluded. As most

biographers, Ginell makes sure to cover the commercially successful

recordings: Milestones, Something Else, Kind of Blue, Nancy Wilson and

Cannonball Adderley, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy, etc. However, Ginell also provides

an overview of Cannonballs lesser-known later recordings in the chapters

titled Accent on Africa, Country Preacher, and As Ambient as All Hell.

Ginell then extends his take on the Adderley canon by devoting three entire

chapters to Cannonballs final work, Big Man, and a live fusion album

recorded in 1971, The Black Messiah (Capitol, 1970). Ginells description of the

musical Big Man is not only a depiction of the work itself but also an account

of Cannonballs final days. Ginell posits the work as the saxophonists magnum

opus. The Adderley brothers spent four years writing and finally recording the

songs for the musical. Unfortunately, Cannonball did not live long enough to

see the 1976 world premiere on-stage.

The emphasis placed on The Black Messiah can be viewed from multiple angles

and will hopefully open some discourse on the importance of Cannonballs

contribution to fusion. Part of what makes Ginells emphasis on the album so

titillating is that the album is somewhat hard to find these days; it has not been

reissued on CD.4 In a sense Ginell is using his power as a biographer to

historically overdub the album onto the Adderley canon. Cannonball was a

pioneer of fusion, but jazz history has forgotten his contributions in favor of

4

As of the time of this writing, The Black Messiah cannot be purchased new on Amazon.com

or other similar sites. However, some of the material can be found on anthologies and

collections like The Definitive Cannonball Adderley (Blue Note), and an import titled Walk Tall:

The David Axelrod Years (EMI).

106

Journal of Jazz Studies

Bitches Brew, Head Hunters, Heavy Weather, and the like. Ginell calls The Black

Messiah an intriguing and overlooked remnant from the early days of jazzrock fusion, and points out that Adderleys band spent much of 1971 and

1972 touring with another fusion forerunner known as the Mahavishnu

Orchestra (145).

Finally, the organization of the book provides a solid framework for a

concise biography. The Foreword by Quincy Jones and Preface by Dan

Morgenstern are immense contributions to the work. Not only did both men

know Adderley personally, but they are both revered figures in the history of

jazz. Jones recalled setting up one of Cannonballs first recording sessions while

Morgenstern describes, among other things, Adderleys participation in the

now infamous Point of Contact debate. Both men carefully describe

Cannonballs demeanor with a personal touch. Jones finishes with a short

paragraph that almost acts as an epitaph. He lovingly ends with As long as I

live, Cannon will always be with us, and deep within our hearts (x).

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

DUSTIN MALLORY is a recent graduate of the Jazz History and Research

Masters program at RutgersNewark. He is a freelance writer and regular

contributor to Cadence, The Independent Journal of Creative Improvised Music.

He is also an active musician/educator near his home in Norristown,

Pennsylvania, where he is currently working on a biography of drummer

Philly Joe Jones.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

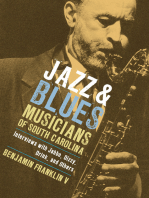

- Jazz and Blues Musicians of South Carolina: Interviews with Jabbo, Dizzy, Drink, and OthersDe la EverandJazz and Blues Musicians of South Carolina: Interviews with Jabbo, Dizzy, Drink, and OthersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sax Heavyweight Sam Dillon On Developing A Jazz Vocabulary, Career Priorities, and More Best. Saxophone. Website. EverDocument7 paginiSax Heavyweight Sam Dillon On Developing A Jazz Vocabulary, Career Priorities, and More Best. Saxophone. Website. Eversolarissparc242100% (1)

- A Lesson From Lester: "Rhythm Changes"Document3 paginiA Lesson From Lester: "Rhythm Changes"Paulo Giovani ProençaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Glide: Sax SopranoDocument1 paginăThe Glide: Sax SopranoFilippoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chris PotterDocument27 paginiChris PotterNareshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhythm Changes Etude 2 AltoDocument1 paginăRhythm Changes Etude 2 AltoMin GloRexÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Favourite Things - John Coltrane Jazz Score - The Sound of MusicDocument11 paginiMy Favourite Things - John Coltrane Jazz Score - The Sound of MusicSimona Simo NataliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhythmic GroupingsDocument4 paginiRhythmic GroupingsJoshua Rager100% (1)

- Dick Oatts - BarbarianDocument3 paginiDick Oatts - BarbarianMichele Polga100% (1)

- Sonny Stitt - Alone TogetherDocument4 paginiSonny Stitt - Alone TogetherMolayjacobo DE MolayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warne Marsh's Blues in Gb Solo TranscriptionDocument5 paginiWarne Marsh's Blues in Gb Solo Transcriptionrit724Încă nu există evaluări

- Open SesameDocument3 paginiOpen Sesameanon-778653Încă nu există evaluări

- Alligator BoogalooDocument1 paginăAlligator BoogalooMaciej CierleckiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jazzrep PDFDocument5 paginiJazzrep PDFjohn0% (1)

- Seamus Blake Glossary PDFDocument1 paginăSeamus Blake Glossary PDFArmen MovsesyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Jazz MessengersDocument16 paginiThe Jazz Messengersandoni_losada350167% (3)

- Meridianne: Wayne Shorter Herbie HancockDocument1 paginăMeridianne: Wayne Shorter Herbie HancockmadcedmadcedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chris Potter PDFDocument11 paginiChris Potter PDFDanielDickinsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Too Close For Comfort: B B B B B B B BDocument2 paginiToo Close For Comfort: B B B B B B B BIgorÎncă nu există evaluări

- FacesDocument3 paginiFacesMiryam MéndezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swinging Man 1Document3 paginiSwinging Man 1Juan VillegasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pentatonic Index II V I SampleDocument8 paginiPentatonic Index II V I Samplemartin.iglesiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- You and the Night and the Music by Bob BergDocument3 paginiYou and the Night and the Music by Bob BergИван СтепаненкоÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foolin' PDFDocument2 paginiFoolin' PDFIsabelle CortvriendtÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mean TimeDocument53 paginiThe Mean Timethe best gaming100% (1)

- Alto Multiphonic FingeringsDocument3 paginiAlto Multiphonic FingeringsJames KarsinoffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eternal Triangle Eb PartDocument1 paginăEternal Triangle Eb PartJerryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dig Dis Hank MobleyDocument2 paginiDig Dis Hank MobleyMicmac53Încă nu există evaluări

- Swangalang PDFDocument32 paginiSwangalang PDFsylvainbeufÎncă nu există evaluări

- Das'Dat - Jackie McLean - Lead SheetDocument1 paginăDas'Dat - Jackie McLean - Lead SheetLallouetÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Tribute To Lee Morgan PDFDocument1 paginăA Tribute To Lee Morgan PDFDamion Hale0% (1)

- Nobody Else But Me BBDocument1 paginăNobody Else But Me BBMiguel Arribas García100% (1)

- Mac1098 Kenny Garrett Dyd Bio Final RevDocument2 paginiMac1098 Kenny Garrett Dyd Bio Final RevAlessio BusancaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oliver Nelson Lick 35: I-VI-ii-VDocument1 paginăOliver Nelson Lick 35: I-VI-ii-VDouglas HolcombÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getz Stella by StarlightDocument2 paginiGetz Stella by StarlightEnrique FlautaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bemsha SwingDocument27 paginiBemsha Swingr-c-a-d100% (2)

- Slow Swing Slow Swing 3 Tim Warfield From "A Cool Blue" (1995)Document1 paginăSlow Swing Slow Swing 3 Tim Warfield From "A Cool Blue" (1995)To TòÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dick OattsDocument2 paginiDick OattsChris SullivanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tom Harrell & Wayne Escoffery - Blue Caribe Comparison ViewDocument3 paginiTom Harrell & Wayne Escoffery - Blue Caribe Comparison ViewBird LivesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charlie Parker - OmniBook EbDocument3 paginiCharlie Parker - OmniBook EbAyud Jazz Trio100% (1)

- Blues HeadsDocument10 paginiBlues Headssaxophonist42Încă nu există evaluări

- Partitura para Trabajo 4 - Transcripción JazzDocument2 paginiPartitura para Trabajo 4 - Transcripción JazzOscarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Billie's BounceDocument3 paginiBillie's BounceAl DaphnéÎncă nu există evaluări

- David Baker - Ear TrainingDocument3 paginiDavid Baker - Ear TrainingLucas Lorenzi100% (1)

- Billie's BounceDocument4 paginiBillie's BounceDana WrightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yes - Mark SoloDocument1 paginăYes - Mark SoloShaul Barkan100% (1)

- The Summit: Lead SheetDocument2 paginiThe Summit: Lead SheetSeth LewisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zoltan1 PDFDocument1 paginăZoltan1 PDFthejackedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhythm Changes Etude 4 Tenor PDFDocument1 paginăRhythm Changes Etude 4 Tenor PDFemanueleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joel Frahm MasterclassDocument3 paginiJoel Frahm MasterclassArmen Movsesyan100% (1)

- Kenny Wheeler Jazz Standard Mark TimeDocument2 paginiKenny Wheeler Jazz Standard Mark TimeStelarson SinnermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plum IslandDocument1 paginăPlum Islandfischermans8316Încă nu există evaluări

- Domingo (Benny Golson)Document1 paginăDomingo (Benny Golson)Leo AlvarezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Measure Licks For The V7 Chord: Name "Bebop" Scale Used by David Baker - Indiana UniversityDocument1 paginăMeasure Licks For The V7 Chord: Name "Bebop" Scale Used by David Baker - Indiana UniversitynevimnicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhythm Changes Etude 4 Alto PDFDocument1 paginăRhythm Changes Etude 4 Alto PDFMattia SonzogniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1 - Sonny Stitt - All God's Chillun Got Rhythm (Eb)Document3 paginiLesson 1 - Sonny Stitt - All God's Chillun Got Rhythm (Eb)戴嘉豪Încă nu există evaluări

- Michael Brecker SolosDocument49 paginiMichael Brecker SolosAlen PavlićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dick Oatts Bird Blues 12 KeysDocument4 paginiDick Oatts Bird Blues 12 KeysHowie Clark50% (2)

- Half NelsonDocument2 paginiHalf NelsonMatthew MaldonadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marketing Analysis PresentationDocument10 paginiMarketing Analysis PresentationFrancesco GiambersioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts Based Initiatives in The WorkplaceDocument51 paginiArts Based Initiatives in The WorkplaceFrancesco GiambersioÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cross Listing Decision PDFDocument53 paginiThe Cross Listing Decision PDFFrancesco GiambersioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines For Leadership AwardsDocument4 paginiGuidelines For Leadership AwardsDindo Arambala Ojeda100% (1)

- HR QuestionsDocument3 paginiHR QuestionsTilak DongaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6-10 Business Letters Writing Exercises ArmelDocument4 pagini6-10 Business Letters Writing Exercises ArmelArcel Varias Esquelito0% (1)

- Department of Education: Contextualized Lesson Plan in Practical Research IiDocument23 paginiDepartment of Education: Contextualized Lesson Plan in Practical Research IiKeziah UbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Case of The Lonely Lady (Intermediate)Document68 paginiThe Case of The Lonely Lady (Intermediate)woraje1834Încă nu există evaluări

- New Developments in The Study of NarrativeDocument12 paginiNew Developments in The Study of NarrativeRehab ShabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivating Kids to ExerciseDocument2 paginiMotivating Kids to ExerciseFlorentina TerghesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 224 School Speech Topics for All GradesDocument3 pagini224 School Speech Topics for All GradesAudrey DiagbelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handicraft Needlecraft CGDocument11 paginiHandicraft Needlecraft CGMeliza Abella100% (1)

- DAILY LESSON LOG OF M8AL-If-1 (Week Six-Day 0ne of Three) : X - and Y-Intercepts (C) The Slope and A Point On The LineDocument7 paginiDAILY LESSON LOG OF M8AL-If-1 (Week Six-Day 0ne of Three) : X - and Y-Intercepts (C) The Slope and A Point On The LineJamillah Ar GaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Format - 4: Eligibility Certificate For Appearing at All India Trade Test AlongwithDocument2 paginiFormat - 4: Eligibility Certificate For Appearing at All India Trade Test AlongwithPradeep KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deloitte Cloud - Task 1 - Client Background & ContextDocument1 paginăDeloitte Cloud - Task 1 - Client Background & ContextsatyamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pidato Bahasa Inggris Be The Success YouthsDocument2 paginiPidato Bahasa Inggris Be The Success YouthsBayu SoetrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appendices SummaryDocument32 paginiAppendices SummaryLynssey DanielleÎncă nu există evaluări

- MSN Comprehensive ExamDocument11 paginiMSN Comprehensive ExamReginah KaranjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benefits and Detrimental Effects of Internet On StudentsDocument10 paginiBenefits and Detrimental Effects of Internet On Studentscheryl limÎncă nu există evaluări

- School Performance, Leadership and Core Behavioral Competencies of School Heads: Does Higher Degree Matter?Document7 paginiSchool Performance, Leadership and Core Behavioral Competencies of School Heads: Does Higher Degree Matter?Manuel CaingcoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- PersuationDocument11 paginiPersuationalpha0125100% (1)

- Jobsfit Report 2020 Vision 03112019Document33 paginiJobsfit Report 2020 Vision 03112019Noelson Codizal100% (1)

- Philippine History Primary SourcesDocument4 paginiPhilippine History Primary SourcesBryan Lester M. Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctor FaustusDocument86 paginiDoctor FaustusAbhishek KashyapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bachelor of Technology with Education Programme StructureDocument3 paginiBachelor of Technology with Education Programme StructureKhairul IzzatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 PretestDocument3 paginiChapter 4 Pretestapi-357279966Încă nu există evaluări

- RPH Cuti-CrkDocument12 paginiRPH Cuti-CrkFrancis JessiusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plumbing 3Document5 paginiPlumbing 3Darwin AgitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Invectives of Sallust and CiceroDocument234 paginiThe Invectives of Sallust and CiceroEster Buonaiuto100% (7)

- 1st Exam - EDENG 1Document3 pagini1st Exam - EDENG 1Joy MagbutongÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2006 Sloan PHD HandbookDocument48 pagini2006 Sloan PHD Handbookboka987Încă nu există evaluări

- B2 First Unit 3 Test: VocabularyDocument2 paginiB2 First Unit 3 Test: VocabularyNatalia KhaletskaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scrivener J. - Classroom Management Techniques - Compressed - CompressedDocument318 paginiScrivener J. - Classroom Management Techniques - Compressed - CompressedBùi Trọng Thuỳ LinhÎncă nu există evaluări