Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

123B 0Q0W D6VN NMB6

Încărcat de

macTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

123B 0Q0W D6VN NMB6

Încărcat de

macDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Int J Psychoanal 2006;87:104958

A review of Lacans seminar on anxiety1

GILBERT DIATKINE

48 bd Beaumarchais, F-75011 Paris, France gilbert.diatkine@wanadoo.fr

(Final version accepted 20 December 2005)

The seminar on anxiety marks a turning point in the development of Lacans

thought from several perspectives. First, Lacan implicitly abandons his theory that

the unconscious is structured like a language. He also abandons the endeavour

to identify Freuds theory with his own. He develops some original new ideas

about anxiety, some of which are of great interest, such as the connection between

castration anxiety and narcissism; others, such as his denial of the existence of

separation anxiety, are absurd. Lacans main point of divergence from Freud, his

rejection of the inner world, also emerges clearly in this seminar.

Keywords: anxiety, object a, jouissance, separation anxiety, intrusion anxiety,

affect

The seminar on anxiety (Lacan, 2004) was held during the academic year 19623.

In 1953, Lacan had produced a ercely polemical manifesto, arguing that the

leaders of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA)Hartmann, Kris

and Loewensteinhad misrepresented Freuds thought and that his own original

ideas concerning a structural identity between psychoanalysis, linguistics and

anthropology constituted a return to genuine Freudian thinking, hitherto misunderstood through hasty readings and faulty translations. In this manifesto, he also put

forward the justication for his most controversial innovation, the practice of short

sessions of varying length. A schism had emerged at this time within the Socit

Psychanalytique de Paris (SPP) and Lacan had become the leader of a new group,

the Socit Franaise de Psychanalyse (SFP), which had requested admission to the

IPA. The year before this seminar, in August 1961, the SFP had been accepted as

a Study Group, and active international negotiations were being conducted for its

admission as an IPA component society at the 1963 Congress. The main obstacle

to this reinstatement was the practice of short sessions, which Lacan saw no reason

to abandon. This is why only a part of the SFP rejoined the IPA in 1963 under

the name Association Psychanalytique de France, while Lacan then created a new

group, outside the IPA, the cole Freudienne de Paris. This diplomatic context may

explain why this seminar was written in a less polemical tone than the previous

ones. It seems to me, however, that Lacans personal development had led him to

accept the originality of his own ideas in relation to those of Freud, and that he

therefore felt less of a need to demonstrate in polemical fashion that he was the only

genuine Freudian.

Translated by Sophie Leighton.

2006 Institute of Psychoanalysis

1050

GILBERT DIATKINE

The end of the return to Freud

In fact, it is interesting to note that in this seminar, instead of striving to demonstrate

at all costs, as he had done previouslynot without some difcultythat his ideas

concurred perfectly with those of Freud, Lacan now identies many vacillations in

Freuds doctrine (2004, p. 377). He clearly sets out where he disagrees with it, so

that the reader can decide more easily on which points he has to choose between

Freud and Lacan, and on which points Lacans contributions usefully amplify

psychoanalytic theory. The divergences primarily relate to the theory of anxiety

as it is developed in Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety (Freud, 1926) (Lacan,

2004, p. 18). For Lacan, the signal of anxiety is not in the ego but in the ideal ego

(p. 138); birth anxiety is not phylogenetic, and he nds the notion of ancestral fear

absurd (p. 74). The childs separation anxiety relates not to the mother but to the

embryonic envelopes (pp. 1423), and the idea of the bedrock of castration that

Freud put forward in Analysis terminable and interminable (1937, p. 252) needs

to be transformed (Lacan, 2004, pp. 58, 161). Freud did not understand very much

about the uncanny (p. 60). Freuds theories of masochism (p. 125) and mourning are

inadequate (p. 132): it is not enough to say that mourning is an identication with

the lost object. We are only in mourning for someone of whom we can say I was

his lack (p. 166). In The psychogenesis of a case of homosexuality in a woman

(1920a), Freud is undoubtedly right to state that the young homosexual womans

scandalous behaviour conceals the unconscious wish to receive a child from her

father: but it is the phallus more than a child that she wants from her father (Lacan,

2004, p. 145). In general, Freud overlooked the question of femininity (p. 152).

However, beyond femininity, it is Freuds entire theory of the inner world that needs

to be challenged (p. 328). Freud also missed the essential point in Totem and taboo

(1913): the important issue is circumcision (Lacan, 2004, p. 239). The concept of

the automatism of repetition is questionable: why should repetition be automatic?

We repeat in order to awaken the memory of God (p. 290). Freud is also wrong to

see the Wolf Mans defaecation during the primal scene as a sacrice. In fact, it is

a passage to the act in the Lacanian sense (p. 301).

With this departure from Freud, Lacan relegates an essential part of his

programme in the Rome discourse (1956). In the discourse, delivered in 1953,

he sought to demonstrate that psychoanalysis was the same as linguistic analysis.

In 19623, Lacan may still have thought that the unconscious is structured like a

language but this ceased to be his watchword. Perhaps because he no longer has

to demonstrate his orthodoxy, here Lacan has stopped forcing himself to distort

Freuds concepts in order to make them accord with his own.

Affect

Affect was particularly ill suited to the above operation, and it had therefore disappeared from Lacanian theory altogether, as Green (1999) has pointed out. Questioned

on television about Greens criticism that he had neglected the question of affect,

Lacan (1990) replied that he had discussed it in his seminar on anxiety (2004). In fact,

the question is dismissed at the very beginning of the seminar (21 November 1962,

A REVIEW OF LACANS SEMINAR ON ANXIETY

1051

p. 29), in which Lacan, commenting on an article by Rapaport (1953), condemns

affect as a blanket psychological term that has no place in psychoanalytic theory.

He goes on to demonstrate this throughout the seminar by gradually drawing up a

two-dimensional picture in which the words from the title Inhibitions, symptoms and

anxiety (Freud, 1926) intersect, along with certain affects such as concern, seriousness and expectation (p. 12). In the course of the year, this picture is lled in from

one session to the next. The nal result is enigmatic (pp. 93, 131; see Table 1).

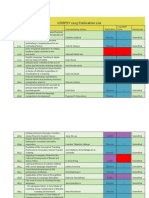

Table 1

Inhibition

Emotion

Agitation

Impairment

Symptom

Acting out

Embarrassment

Passage to the act

Anxiety

Something that appears nonsensical in a Lacanian text can always testify to the

readers intellectual incapacities. However, it can also indicate that Lacan regards

the problem posed as meaningless. Lacan did not change his views on the question

of affect: you can invent as many affects as you like, and interconnecting them is

even less worthwhile than Freud (1926), an essential reference point for American

analysts and the main target of Lacans critique. There is only one affect that interests

Lacan: anxiety.

Anxiety

Anxiety about returning to the mothers breast

This seminar is very unusual in containing two excerpts from Lacans own clinical

practice. One is a clinical extract (Lacan, 2004, p. 219) and the other is the following

fantasy.

Lacan imagined himself, wearing a mask, facing a huge female praying mantis,

not knowing whether she thinks he is male or female because he cannot see himself

in her gaze (p. 14). What does she want from him? (Che vuoi?) The fantasy of

returning to the maternal breast, which for others is the ultimate image of happiness,

is for Lacan the primary source of every form of anxiety (p. 215). What causes

anxiety is everything that tells us or enables us to see that we are going to go back to

her lap (p. 67). This type of anxiety plays an important role in the psychopathology

of romantic love, in which a subject, having obtained the favourable response that

he desired from the loved object, suddenly draws back, wondering what the other

person is going to do to him, illustrating the essential relationship of anxiety to the

desire of the Other: What does he/she want from me? (p. 14). It also appears almost

constantly in the impulse by which adolescents free themselves of their maternal

objects. The fear that excessive maternal concern will lead to the elimination of the

subjects desire is primordial for Lacan: What is most anxiety provoking for the

child is precisely when the relation on which he founds himself, from the lack that

produces desire, is disturbed, and it is most disturbed when there is no possibility of

lack, when the mother is on his back all the time, specially to wipe his bottom, as a

model of the demand, of the demand that could never falter (p. 67).

1052

GILBERT DIATKINE

It was also by giving a central position to this type of anxiety that Jean Laplanche,

a student of Lacan who broke with him at an early stage, went on to develop his own

theory of enigmatic signiers: what does this breast that is approaching me want

from me?

Castration anxiety

Secondary to this anxiety about returning to the mothers breast is castration anxiety,

which Lacan describes as a total captivation by the mirror image (p. 19). The only

form of resistance to this threat of absorption is the autoerotic cathexis of the phallus,

which constitutes a libidinal reserve (p. 57) for the subject. This results in a break in

the specular image, which forms the basis for Lacans theory of the castration fantasy.

The only thing that protects the subject from his desire to be absorbed by Others

mirror image is a massive phallic cathexis. In this theory, the castration fantasy is no

longer an infantile sexual theory that results from the confrontation of the subjects

sexual desires with the reality of sexual difference, as with Freud, but relates solely

to narcissism and to a conception of narcissism that is itself highly specic, based on

the relation to the mirror image. Besides, Lacan also accepts in more classical terms

that castration anxiety is therefore connected with the perception of sexual difference, which he expresses in his terminology by stating that it arises when the phallic

lack appears in the place of the object of desire (p. 53). The idea that a libidinal

reserve is constituted at the threshold of a love relationship that appears to satisfy

all the subjects desires provides a good account of some paradoxical behaviours,

such as the sexual adventures that certain subjects embark on with despised gures

just before a marriage to a loved object. Lacans concept therefore constitutes a

useful supplement to Freuds theory.

Separation anxiety

In contradiction to common experience, on several occasions Lacan denies the

reality of separation anxiety. Many witnesses have described Lacans distress when

one of his patients, infuriated, put an end to the treatment. He was very well aware

of the anxiety provoked by loss of the object. Notwithstanding this, Lacan asserts

several times that it is not the absence but the presence of the mothers breast (p. 66)

or of the object in general (p. 67) that causes anxiety. He turns Freuds demonstration in Beyond the pleasure principle (1920b) on its head: if the child throws the

bobbin away, this is not in order to master its disappearance but to remove a source

of anxiety (Lacan, 2004, p. 80)! As it is nevertheless very difcult to argue that there

is no such thing as separation anxiety, Lacan concedes that the child experiences an

anxiety about separationnot from the mother but from the embryonic envelopes!

These envelopes are still only parts of the child, detachable from him, just like the

breast. It is therefore not the child who is sucking the breast; it is the breast and the

placenta that are sucking the mothers body (pp. 195, 337).

Birth anxiety

For Lacan, it is this anxiety about separation from the embryonic envelopes that

accounts for birth anxiety, and not, as Freud believes, some form of phylogenetic

A REVIEW OF LACANS SEMINAR ON ANXIETY

1053

reproduction (p. 142). Moreover, the anatomical model of the relations between

the placenta and the foetus is fairly similar to one of the geometrical shapes that

represent for Lacan the new topography of the psychic space that he has invented,

namely the cross-cap (p. 143). However, birth anxiety is predominantly an anxiety

about intrusion (air into the lungs) and not an anxiety about leaving the maternal

environment (pp. 3778).

Signal anxiety

Signal anxiety therefore does not alert to the alleged loss of the penis or reproduce

a supposed phylogenetic event; it is only the signal of the failure of support that

comes from lack to protect the subject from returning to the lap, that is losing

himself completely in the specular image. Freud was mistaken. There is no internal

danger but only an anxiety about the Other: Although the ego is the site of the

signal, it is not for the ego that the signal is given. The signal warns the ego that the

Other desires it and is therefore seeking to annihilate it (p. 179).

Jouissance

Why is the ego at risk of being annihilated by the desire of the Other? First, as we

have seen, because it can be absorbed entirely by the specular image that the Other

represents for him, like Narcissus in the myth; second, because even if the subject

has secured this absorption for himself through castration anxiety, he is exposed to a

second, yet more formidable, danger. A child being held by his mother in the mirror

does not only see his own image and that of his mother, by which he wants to be

absorbed. He also sees that he is not adequate to satisfy his mother, and that there

is something that exists other than him, which she does not have and which arouses

her desire: the fathers phallus. This phallus appears solely as that which is lacking

in the Other, and therefore only as castrated, which Lacan denotes (pp. 53, 197).

Although making oneself the object of the mothers desire is always hazardous, there

is a more certain means of attaching the Other to oneself, which is to make oneself

the cause of her desire, by identifying with this castrated phallus. This is what Lacan

means by becoming the object of the Others jouissance. In the castration fantasy,

although the subject loses a valuable component of his specular image, he may also

acquire an identication with a faecalized, fallen and deposed object, which will be

certain to provoke the Others jouissance.

It appears at rst that in describing jouissance, Lacan is merely emphasizing

the role of the Other in that which Freud has long since described using the term

moral masochism. The existence of moral masochism is Freuds main clinical

argument in support of the death drive (1924). Without taking an explicit standpoint

on the question of the death drive, Lacan also situates that which he calls jouissance

beyond the pleasure principle (2004, pp. 148, 213). In this sense, jouissance is

radically different from orgasm, and the small amount of satisfaction that it brings

(p. 303). It is well known that neurotics unconsciously enjoy their symptoms and

therefore that the symptom is jouissance (p. 148). We did not need to wait for Lacan

to describe couples, or parentchild relationships, in which a subject prefers to be

1054

GILBERT DIATKINE

the faecalized object of the partners jouissance than to nd pleasure in a mutual

relationship. We are probably more indebted to Lacan for having demonstrated that

if the analyst reveals to the patient his desire to cure or to teach him, he simultaneously indicates to him how to make himself the object of his jouissance, by staying

ill or remaining stricken by intellectual inhibition.

The object a

The most certain way of becoming the object of the Others desire is therefore to

make oneself the cause of his jouissance by becoming his part object. However,

Lacan rejects the term part object because Freud (1926) regards the various part

objects as objects from which it is possible to separate, and Lacan will brook no

reference to separation anxiety.

The breast, the phallus, the scybalum and the childFreuds part objects

(1926)are what Lacan terms objects a. However, Lacan describes many

others, such as the foreskin in circumcision (2004, p. 247), the eye (p. 276), the

voice (p. 342), the superego (p. 341) and even Jesus Christ, who makes himself an

object a in the Passion, as a residue, fallen object, for the Other, God (p. 192).

The object a causes anxiety not because it might be lost but because it might

have to be shared (pp. 53, 107). It is never a case of an object being lost by the

subject, but objects lacking in the Other (p. 337). The object a is not the object

of the subjects desire but its cause (p. 323). The object a is that which eludes

specularization and signiantisation (p. 204).

The object a is itself the representative of a thing that is unnameable and

unrepresentable for the Other (p. 148). This is reminiscent of those subjects who,

constantly behaving abjectly towards those close to them, restore to life before their

eyes objects that have been lost to the previous generation in conditions that cannot

be represented in any other way.

Love

This theory of jouissance and the object gives rise to a disillusioned view of love,

since there is no better means of making oneself loved than to become a castrated

phallus and thus to be for the Other that which one does not have oneself (p. 139):

the formula love is giving what you do not have (p. 128) is the new watchword

which, in this seminar, replaces the unconscious is structured like a language.

The rejection of interiority

The object a initially appears as that which resists assimilation by the Other, and

therefore as the guarantor of the separation between ego and non-ego (p. 121).

However, the space in which the psychic events described by Lacan occur is not

well adapted to the internal/external distinction (pp. 290, 328). There is no internal

danger and the neurological apparatus has no interior (p. 179).

For the model that Freud proposes in The ego and the id (1923), in which the

psychic apparatus, with ego, id and superego, confronts the external world, Lacan

A REVIEW OF LACANS SEMINAR ON ANXIETY

1055

substitutes various models without interior or exterior, such as Kleins bottle (p. 238)

or the Mbius strip, which has only one surface, so that by following it from one

end to the other you move from one side to the other without crossing it (p. 116). To

move from one side of the Mbius strip to the other, you have to make a hole in it:

the hole is the object a. However, this hole cannot be symbolized (p. 161). Like the

object a, the Mbius strip therefore has no specular image (p. 110). Conversely, the

object a has the shape of the Mbius strip.

The cross-cap (pp. 13, 51, 113, 115, 143) is another topographical model that

has both an exterior and an interior but in section it is the shape of an inner eight,

which resembles the Mbius strip (p. 115). Topographical shapes like the crosscap exist in nature (p. 377). For example, embryonic envelopes have this structure

(p. 143). This explains Lacans enduring interest in embryonic envelopes and the

placenta (pp. 1423, 195, 267).

Passage to the act and acting out

French analysts used to translate the term acting out by passage lacte (literally,

passage to the act). Lacan draws a distinction between passage to the act and acting

out (pp. 93, 135, 372). Passage to the act is the leap into the void at the moment of

conjunction between desire and the law (p. 130); i.e. the identication with an object

a and the simultaneous condemnation of this identication by the subject whose desire

was in fact thought to be provoked by this identication (p. 131). The object a is that

which is dropped (p. 136). Lacan gives the example (p. 145) of the young homosexual

woman seen in consultation by Freud (1920a), who had thrown herself off a bridge

after being seen by her father in the company of the woman she loved.

In the passage to the act, the subject leaves the scene (p. 136). In acting out,

however, the subject remains on the scene. We might suppose the scene to be the

psychic scene or the scene of the transference, in which case acting out would be

an act that could be interpreted. However, Lacan gives it a broader denition. The

scene is the scene of the Other, which exists in every relationship between two

people. It stands in contrast to the world. The world is the place in which the real

occurs (p. 137). When Freuds homosexual woman throws herself on the tracks,

this is a passage to the act because the judgement read in her fathers gaze removes

her from her position as cause of his desire. When she has an affair with the Lady,

this is acting out because nothing that occurs between her and the lady has dislodged

her from this position as subject.

Similarly, in the Dora case (Freud, 1905), when Dora slaps Mr K, this is a

passage to the act, because Mr Ks declaration, You know I get nothing out of

my wife (p. 98), has dislodged her from her position as cause of desire for the two

members of the couple. When she has had a love story with Mr and Mrs K, this is

acting out, because nothing that has occurred has deprived her of this position.

Femininity

Lacan takes a rm stance against Freuds theory of penis envy in women (pp.

152, 211, 214). He draws (without naming it) on Andreas-Saloms theory of

1056

GILBERT DIATKINE

the location of the vagina in the anus (1916) to deny the existence of alleged

vaginal jouissance on the grounds that the vagina is insensitive (Lacan, 2004,

p. 307). Here, jouissance has to be understood in the orgasmic sense. However,

if we distinguish jouissance from orgasm, the female orgasm occurs at a fairly

primitive point and is therefore older than the existing compartmentalization of

the cloaca (p. 307). It is therefore easier for women than men to put themselves

in the position of the object a for the Other. They have a simpler relationship

to the desire of the Other (p. 214) and a better understanding than men of the

relationship of desire to jouissance (p. 208). This means that female analysts have

an easier access to their countertransference and it is therefore no surprise that it

should be mainly women who have written on this subject (pp. 208, 214).

Unlike men, women are not afraid of losing their phallus (p. 214) since they

dont have it (p. 233), but they are afraid of provoking castration anxiety in men

(p. 58; see also Cournut-Janin and Cournut, 1993). The womans object a is the lost

member of Osiris or the sacred heart of Marie Alacoque, or alternatively the priests

penis for the woman who loves priests. Don Juan is a female fantasy, that of an

uncastratable man (p. 233). Adopting the more traditional hypothesis of the woman

as phallus, Lacan writes that the woman presents herself as a non-detumescent

phallus (p. 308).

The analytic process

The analytic process consists in the successive abandonment of every form of

identication with the object a of the Other: It is to the extent to which you leave

the demand unanswered that there arises what? Not aggression followed by

regression, but a

re-examination of that which aggression intrinsically seeks out, namely the relation to the

specular image. It is the extent to which the subject exhausts his passions on this image

that determines the emergence of this series of demands, leading to an ever more original

demand, in historical terms, and that regression as such is modulated. (p. 65)

There is no genetic reconstruction but there is a reinterpretation of the bedrock

of castration: In fact, it is to the extent to which all the forms of the demand are

exhausted to their term, to the end of the line, until the zero demand, that we see the

relation of castration emerge.

Newspeak

Lacan always deploys paradoxical formulations that have a shock effect and pose

a challenge to received ideas. They occur particularly frequently in his seminar on

anxiety. For example:

It is not castration from which the neurotic draws back; it is making of his castration that

which the Other lacks [p. 58].

Do you not realize that it is not the nostalgia for the maternal breast that engenders anxiety,

but its imminence? [p. 66].

The security of presence is the possibility of absence [p. 67].

It is not a question of loss of the object but its presence; objects are not missed [p. 67].

A REVIEW OF LACANS SEMINAR ON ANXIETY

1057

What is the relation of desire to the law? Answer: It is the same thing. Desire is the law [p. 97].

The castration of the complex is not a castration [pp. 113, 125].

After all, the mother herself is not the most desirable object [p. 125].

Anxiety is the signal of the real [p. 188].

The object of male desire is the absence of the phallus [pp. 215, 231].

Metaphor does not oppose the intrinsic meaning to the represented meaning [p. 250].

Of all the forms of anxiety, orgasm is the only one that really ends [p. 275].

The phallus constitutes castration itself [p. 308].

These pervasive shock formulae often form the introduction to an interesting new

idea. Sometimes, they are rank absurdities, such as the idea that the mother is not

desirable to the child. Their abundance ultimately leaves the reader with a sense of

having read them somewhere before. They are reminiscent of the Newspeak watchwords from the Ministry of Truth in George Orwells 1984 (1954, p. 7), which were

themselves inspired by communist slogans such as the democratic dictatorship of

the proletariat:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

This is not a new comparison. The abrupt alternations between seduction and threat

that characterize Lacans oratorical style in his seminar, in which his patients participated, have often been compared with the police technique of brainwashing. Lacan

knows this and replies to itin Newspeak. It is extremely good for a psychoanalyst

to wash his brainof his erroneous ideas:

Therefore, what I am evoking for you here is not metaphysics. It is rather a form of

brainwashing.

This is a term that I had allowed myself to use a few years before it was done any injury by

current events. What I mean by this is a method of teaching you how to recognize that which

appears in your experience in its correct position

I may sometimes have been criticized for the presence of some of my analysands in my

seminars. After all, the legitimacy of this coexistence of these two relationships with me

listening to me and having me listen to youcan only be judged from the inside

As I said, brainwashing (2004, p. 85)

There could be no better way of expressing it.

Translations of summary

Eine Neubetrachtung von Lacans Seminar ber Angst. Das Seminar ber Angst markiert in

verschiedenerlei Hinsicht einen Wendepunkt in der Entwicklung von Lacans Denken. Erstens rckt Lacan

implizit von seiner Theorie ab, dass das Unbewusste wie eine Sprache strukturiert sei. Er verzichtet auch auf

den Versuch, Freuds Theorie mit seiner eigenen in eins zu setzen. Er entwickelt neue, originelle Ideen ber

die Angst, die zum Teil, wie beispielsweise die Verbindung zwischen Kastrationsangst und Narzissmus,

auerordentlich wichtig sind; andere, etwa seine Verleugnung der Existenz von Trennungsangst, sind

absurd. Der wichtigste Punkt, in dem Lacan von Freud abweicht, nmlich seine Ablehnung einer inneren

Welt, wird in diesem Seminar ebenfalls deutlich.

Una resea del seminario de Lacan sobre la angustia. El seminario sobre la angustia marca un punto

crucial en el desarrollo del pensamiento lacaniano desde varias perspectivas. Primero, Lacan implcitamente

abandona su teora de que el inconsciente est estructurado como un lenguaje. Tambin abandona el intento

1058

GILBERT DIATKINE

de identicar la teora de Freud con la suya propia. Lacan desarrolla algunas nuevas y originales ideas

sobre la angustia, algunas de gran inters, como la conexin entre la angustia de castracin y el narcisismo;

otras, en cambio como la negacin de la existencia de la angustia de separacin, son absurdas. La principal

divergencia de Lacan con Freud es su rechazo del mundo interno, lo cual tambin surge claramente en este

seminario.

Compte-rendu de Langoisse de Lacan. Le sminaire sur Langoisse marque un tournant dans lvolution

de la pense de Lacan plusieurs points de vue. Lacan y renonce implicitement sa thorie que linconscient

est structur comme un langage. Il cesse de chercher identier la thorie de Freud la sienne propre. Il

dveloppe de nouvelles ides originales sur langoisse, les unes trs intressantes, comme le lien quil

tablit entre langoisse de castration et le narcissisme, les autres absurdes, comme le dni de lexistence

de langoisse de sparation. Sa diffrence principale avec Freud, son refus du monde intrieur, apparat

clairement dans ce sminaire.

Resoconto del seminario di Lacan sullangoscia. Il seminario sullangoscia segna una svolta importante

nello sviluppo del pensiero lacaniano sotto diversi punti di vista. Innanzitutto, Lacan abbandona

implicitamente la teoria secondo la quale linconscio strutturato come un linguaggio. Abbandona inoltre

il tentativo di identicare la teoria di Freud con la propria. Sviluppa poi nuove idee originali sullangoscia,

alcune molto interessanti, come il nesso che stabilisce fra angoscia di castrazione e narcisismo; altre invece,

come il suo diniego dellesistenza dellangoscia di separazione, risultano assurde. In questo seminario

emerge inoltre chiaramente il suo riuto dellesistenza di un mondo interiore che costituisce la sua maggiore

divergenza da Freud.

References

Andreas-Salom L (1916). Anal und sexual [Anal and sexual]. Imago 4:24973.

Cournut-Janin M, Cournut J (1993). La castration et le fminin dans les deux sexes [Castration

and the feminine in the two sexes]. Rev Fr Psychanal 57(suppl):13538.

Freud S (1905). Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria. SE 7, p. 3122.

Freud S (1913). Totem and taboo. SE 13, p. 1161.

Freud S (1920a). The psychogenesis of a case of homosexuality in a woman. SE 18, p. 14772.

Freud S (1920b). Beyond the pleasure principle. SE 18, p. 764.

Freud S (1923). The ego and the id. SE 19, p. 366.

Freud S (1924). The economic problem of masochism. SE 19, p. 15770.

Freud S (1926). Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety. SE 20, p. 77174.

Freud S (1937). Analysis terminable and interminable. SE 23, p. 21653.

Green A (1999). The living discourse: The psychoanalytic conception of affect [1973]. London:

Routledge. 320 p.

Lacan J (1956). The function and eld of speech and language in psychoanalysis. In: crits,

Fink B, translator, p. 197268. New York, NY: Norton, 2005. [Fonction et champ de la parole

et du langage en psychanalyse. In: crits, p. 237322. Paris: Seuil, 1966.]

Lacan J (1990). Television: A challenge to the psychoanalytic establishment, Copjec J, editor,

Hollier D, Krauss R, Michelson A, translators. New York, NY: Norton. [(1974). Tlvision.

Paris: Seuil. 72 p. (Le champ freudien.)]

Lacan J (2004). Le sminaire, Livre X: Langoisse [The seminar, Book 10: Anxiety] [19623],

Miller JA, editor. Paris: Seuil. 382 p.

Orwell G [Blair E] (1954). 1984. London: Penguin. 352 p. [(1950) 1984, Audiberti A, translator.

Paris: Gallimard. 438 p. (Folio.)]

Rapaport D (1953). On the psycho-analytic theory of affects. Int J Psychoanal 34:17798.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Ex2 SystemDocument78 paginiEx2 SystemAllan B80% (5)

- Intro To ZentangleDocument5 paginiIntro To Zentangleapi-457920671Încă nu există evaluări

- David Deida - On How To Attract So Many Women You Will Have To Eliminate ThemDocument14 paginiDavid Deida - On How To Attract So Many Women You Will Have To Eliminate ThemKate Hucack100% (1)

- Lacan and AddictionDocument257 paginiLacan and Addictionmac100% (12)

- Positive Psychology BooksDocument6 paginiPositive Psychology BooksSelectical infotech100% (1)

- 11 2 Multi-Step Subtraction ProblemsDocument2 pagini11 2 Multi-Step Subtraction Problemsapi-291287741Încă nu există evaluări

- The Grip of Ideology: A Lacanian Approach To The Theory of IdeologyDocument25 paginiThe Grip of Ideology: A Lacanian Approach To The Theory of IdeologymacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Umbra Aesthetics and Sublimation 1999Document86 paginiUmbra Aesthetics and Sublimation 1999macÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbstractBook CPSYC 2015Document58 paginiAbstractBook CPSYC 2015macÎncă nu există evaluări

- Istanbulpublicationlist2015 CpsycDocument23 paginiIstanbulpublicationlist2015 CpsycmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economies of Excess: ParallaxDocument3 paginiEconomies of Excess: ParallaxmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of The American Psychiatric Nurses Association-2006-Kutney-22-7Document6 paginiJournal of The American Psychiatric Nurses Association-2006-Kutney-22-7macÎncă nu există evaluări

- J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2012 Kirshner 1223 42Document20 paginiJ Am Psychoanal Assoc 2012 Kirshner 1223 42macÎncă nu există evaluări

- From The SAGE Social Science Collections. All Rights ReservedDocument12 paginiFrom The SAGE Social Science Collections. All Rights ReservedmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Body & Society 2005 Aho 1 23Document23 paginiBody & Society 2005 Aho 1 23macÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy Today Fall 2009 53, 3 Proquest Research LibraryDocument21 paginiPhilosophy Today Fall 2009 53, 3 Proquest Research LibrarymacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uq351611 OaDocument38 paginiUq351611 OamacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75Document28 paginiJournal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75macÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75Document28 paginiJournal of Research in Crime and Delinquency-1990-GROVES-348-75macÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art:10.1007/s11841 008 0078 ZDocument14 paginiArt:10.1007/s11841 008 0078 ZmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: KarlssonDocument13 paginiIntroduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: KarlssonmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: KarlssonDocument13 paginiIntroduction To Phenomenological Psychological Research: KarlssonmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zizek Avec BadiouDocument14 paginiZizek Avec BadiouJoshua BarnesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parrhesia12 MeillassouxDocument11 paginiParrhesia12 MeillassouxBenny Apriariska SyahraniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theatre of Alain BadiouDocument12 paginiTheatre of Alain BadioumacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alain Badiou-The Event in DeleuzeDocument8 paginiAlain Badiou-The Event in DeleuzeonesplitsintotwoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nirenbergs Badiousnumber Complete PDFDocument32 paginiNirenbergs Badiousnumber Complete PDFRui MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- HallwardDocument3 paginiHallwardmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- 22 1-2 GirouxDocument14 pagini22 1-2 GirouxmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagonals NorrisDocument39 paginiDiagonals NorrismacÎncă nu există evaluări

- DocDocument9 paginiDocmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- ContentDocument23 paginiContentmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jenkins 2012 Philosophy CompassDocument10 paginiJenkins 2012 Philosophy CompassmacÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Lippitt - Nietzsche, Zarathustra and The Status of LaughterDocument11 paginiJohn Lippitt - Nietzsche, Zarathustra and The Status of LaughterMarelin Hernández SaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Owen-2003-European Journal of PhilosophyDocument24 paginiOwen-2003-European Journal of PhilosophymacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Posthuman BodiesDocument281 paginiPosthuman BodiesKasraSr100% (1)

- 9.21 GER210 Lecture NotesDocument2 pagini9.21 GER210 Lecture NotesLiting ChiangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital FootprintsDocument2 paginiDigital FootprintsOfelia OredinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MODULE 9: Personal Relationships: Albert Abarabar, Erica Soriano, Lloyd Sarandi, Julius Dela CruzDocument18 paginiMODULE 9: Personal Relationships: Albert Abarabar, Erica Soriano, Lloyd Sarandi, Julius Dela CruzMark Gil GuillermoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of Planned Behavior - WikipediaDocument9 paginiTheory of Planned Behavior - Wikipediawaqas331100% (1)

- Coleridge - Biografia Literaria - 10, 13, 14Document12 paginiColeridge - Biografia Literaria - 10, 13, 14AdamalexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Session 0 Leveling of Expectations Grade 9Document4 paginiSession 0 Leveling of Expectations Grade 9Dhan BunsoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- External and Internal Environment of Organization PDFDocument2 paginiExternal and Internal Environment of Organization PDFMarc100% (1)

- Bruxaria e Historia Cultural PDFDocument25 paginiBruxaria e Historia Cultural PDFGeorge Henri FernandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rubric For Final ProjectDocument3 paginiRubric For Final ProjectMark Gura100% (1)

- Beta B - I1 Form (Debraj Chatterjee)Document2 paginiBeta B - I1 Form (Debraj Chatterjee)Vindyanchal KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: A Case Study of Hotel Industry in VietnamDocument14 paginiService Quality and Customer Satisfaction: A Case Study of Hotel Industry in VietnamkaiserousterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salary NegotiationDocument1 paginăSalary Negotiationtempo97217483Încă nu există evaluări

- Emmas Crazy Day PDFDocument11 paginiEmmas Crazy Day PDFCC CCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rosemarie Rizzo Parse's Theory of Human BecomingDocument17 paginiRosemarie Rizzo Parse's Theory of Human BecomingCINDY� BELMESÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Connection Between Strategy and Structure: Published by Asian Society of Business and Commerce ResearchDocument12 paginiThe Connection Between Strategy and Structure: Published by Asian Society of Business and Commerce ResearchPranav KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faculty Survey 2019Document8 paginiFaculty Survey 2019api-484037370Încă nu există evaluări

- Attributes and Skill Required of A Counsellor 2Document19 paginiAttributes and Skill Required of A Counsellor 2simmyvashishtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Itroduction To LinguisticsDocument3 paginiItroduction To LinguisticsLaura BenavidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- RPH ActivityDocument5 paginiRPH ActivityChristian Gabriel Gonsales Plazo100% (2)

- Shine From Within - Konko GuidebookDocument80 paginiShine From Within - Konko GuidebookStephen Willis100% (1)

- 100 Report Card Comment IdeasDocument7 pagini100 Report Card Comment IdeasVanessa Sabanal BenetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jungian SpaceDocument9 paginiJungian SpaceArkava DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Choosing A Mixed Chapter 4Document32 paginiChoosing A Mixed Chapter 4yochai_ataria100% (1)

- M4.11 Eng102 Apa PDFDocument34 paginiM4.11 Eng102 Apa PDFjeanninestankoÎncă nu există evaluări