Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ryan Patrone's Thesis - Improper Capitalization of Expenditures Who Dropped The Ball

Încărcat de

Lương Thế CườngTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ryan Patrone's Thesis - Improper Capitalization of Expenditures Who Dropped The Ball

Încărcat de

Lương Thế CườngDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Improper Capitalization of Expenditures:

Who Dropped the Ball?

Ryan Patrone

Spring 2012

Patrone1

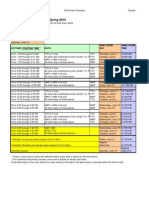

Table of Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................................2

Thesis ...............................................................................................................................................3

Appendix A ....................................................................................................................................18

Appendix B ....................................................................................................................................19

Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................20

Patrone2

Abstract

From 2000 through 2002, WorldCom improperly capitalized fees charged by third party

telecommunication network providers for access rights to their networks. During this time

period, the company overstated earnings by more than $3.8 billion. Though it has been

proclaimed that WorldComs improper capitalization of expenditures is indicative of

fundamental issues underlying the rules-based approach of U.S. GAAP, the standards themselves

were actually inconsequential to the development of the WorldCom scandal.

WorldComs access fees were improperly accounted for relative to both GAAP and the

more principle-based IFRS. The company would have actually found it easier to support its

fraudulent activity had it been following principle-based standards. By claiming that the line

costs were a cost of obtaining customers, managers could align the improper treatment with the

objective of capitalizing expenditures: matching expenses with the revenues they helped to

generate. Rather, the scandal was a product of ineffective controls and issues with the structure

and integrity of management. As is the case with most fraudulent activity, managements lack of

integrity was at the core of WorldComs scandal. Fueled by greed, executives violated basic

ethical principles and their managerial responsibilities to shareholders in order to temporarily

inflate profits. The companys highly bureaucratic structure enabled the executives to control the

accounting methods and created barriers to detection and corrective action. These barriers,

coupled with the internal audit teams lack of competence and independence, contributed to the

ineffectiveness of the companys control mechanisms. The last line of defense against the

fraudulent activity and related financial misstatements was the external audit function, which

failed due to the absence of professional skepticism and independence.

Patrone3

Thesis

WorldCom was a major global communications provider of data transmission and

telecommunication services. From 2000 through 2002, the company improperly capitalized fees

charged by third party telecommunication network providers for access rights to their networks

(line costs). During this time period, WorldCom overstated earnings by more than $3.8

billion. The collapse of the telecommunications giant resulted in the loss of more than 17,000

jobs and billions of dollars in pensions and investments (Knapp, 2010, p. 327). Though it has

been proclaimed that WorldComs improper capitalization of expenditures is indicative of

fundamental issues underlying the rules-based approach of U.S. GAAP, the accounting fraud

was actually a result of ineffective internal and external controls, the companys highly

bureaucratic structure, and a lack of integrity among the executive officers.

In a statement made by WorldCom on June 25th, 2002, the company admitted that it had

improperly capitalized over $3.8 billion of line costs. According to European Union Briefings,

the WorldCom scandal undermined investors confidence in the superiority of US GAAP and

suggested fundamental problems with rules-based standards (European Union Center of North

Carolina, 2007). Relative to rules-based accounting standards, principle-based standards

increase the application of professional judgment. This increase should promote a focus on

economic substance over form, resulting in higher quality financial information. Nonetheless,

the absence of principle-based standards was irrelevant to WorldComs fraudulent activity.

Financial Accounting Standard 13.1 defines a lease as an agreement conveying the right

to use property, plant or equipment usually for a stated period of time (Ernst & Young, 2005, p.

453). International Accounting Standard 17.4 offers a similar definition, describing a lease as

an agreement whereby the lessor conveys to the lessee in return for a payment or series of

Patrone4

payments the right to use an asset for an agreed period of time (Ernst & Young, 2005, p. 452).

WorldComs line costs represented fees in exchange for rights of access to other companies

assets, and hence qualify as leases under both GAAP and IFRS.

IAS 17.4 and 17.8 indicate that a lessee should account for a lease as a finance lease

when the lease transfers substantially all the risks and rewards incidental to ownership to the

lessee, even if title is not transferred. All other leases are operating leases (Ernst & Young,

2005, p. 460). The section goes on to list several qualities that indicate, but do not necessarily

require, that a contractual arrangement should be categorized as a finance lease. These include

the transfer of ownership to the lessee by the end of the lease term, the existence of a bargain

purchase option, the lease term being for the major part of the assets economic life, the present

value of the minimum lease payments amounts to at least substantially all the fair value of the

leased asset, or the leased assets are of such a specialized nature that only the lessee can use them

without major modifications (Ernst & Young, 2005, p. 462). WorldComs contractual

arrangements with third parties did not contain any of these indicators.

Additionally, the lessors of the telecommunications lines retained the major risks and

rewards of ownership: they depreciated the assets on their books, bore the risk of obsolescence,

and were accountable for maintaining the lines. This indicates that WorldComs leasing

arrangements did not align with the conceptual foundation set forth by IAS 17 for financing

leases: that substantially all risks and rewards incidental to ownership be transferred.

Financial Accounting Standard 13 states that a lease is required to be treated as a capital

lease if any of a number of criteria is met. Otherwise, the lease should be classified as an

operating lease. The criteria set forth are the transfer of ownership to the lessee by the end of

the lease term, the existence of a bargain purchase option, the lease term being for seventy-five

Patrone5

percent or more of the leased assets estimated economic life, or the present value of the

minimum lease payments being greater than or equal to ninety percent of the fair value of the

asset to the lessor at the inception of the lease less any investment tax credit retained by the

lessor (Ernst & Young, 2005, p. 463).

Consequently, under both International Financial Reporting Standards and Generally

Accepted Accounting Principles, WorldComs line costs should have been recorded in

compliance with the methods set forth for operating leases. Such methods prescribe that the

expenses be reported as line items on the income statement for the appropriate periods, not

capitalized as was the case with WorldCom. Furthermore, consistent with IAS 17 and FAS 13,

under a finance or capital lease the lessee must recognize an asset and a liability on its balance

sheet at the inception of the lease (Ernst & Young, 2005, p. 462). Even if WorldComs

contracts had qualified as capital leases, the company failed to record any assets on its balance

sheet at the onsets of the agreements (refer to Appendix A). WorldCom instead used adjusting

journal entries to capitalize its line costs, further violating the provisions set forth by IAS 17 and

FAS 13 (refer to Appendix B).

In order for GAAPs rules-based nature to be the primary cause of the misclassification,

WorldCom would have had to mislead investors while complying with the rules of GAAP.

However, since the companys line costs were accounted for improperly relative to both IFRS

and GAAP, the sustainment of WorldComs accounting fraud must be a product of other factors.

The European Union Briefings cited the WorldCom case as an illustration of a major criticism

with GAAP: companies can strictly adhere to the rules-based standards while not respecting their

conceptual foundations. Accepting this criticism as true and ignoring the fact that WorldCom

was not in compliance with the rules of GAAP, it must be noted that the deliberate

Patrone6

misrepresentation of financial substance typically requires some degree of unprofessionalism or

deceitful intent.

Contrarily, the Briefings state that the imprecise nature of principle-based standards

makes it more difficult for accountants to exploit loopholes in the wording of the standards

(European Union Center of North Carolina, 2007). With principle-based standards, the absence

of precise guidelines increases the scale and frequency of professional judgment. As previously

mentioned, the augmented application of professional judgment should theoretically result in

higher quality financial information. However, given the existence of the deceitful intent

necessary for financial misrepresentation under rules-based standards, this increase in

professional judgment enables accounting fraud. As a result of inherent flexibility of principlebased standards, accounting records can be distorted through innovative interpretations of

economic substance. Accordingly, in the presence of unprofessionalism, disregard for

conceptual foundations can result in slanted financial information under both rules-based and

principles-based standards.

Moreover, in the case of WorldCom, the company likely would have found it easier to

rationalize its fraudulent activity had it been acting in accordance with principle-based standards.

According to the July 4th New York Times, a June 24th memo prepared by Sullivan attempted to

justify the capitalization by arguing that WorldCom was paying for excess capacity that it would

need in the future (Lyke & Jickling, 202). By claiming that the fees were a cost of obtaining

customers, Sullivan aligns the improper accounting treatment with the objective of capitalizing

expenditures: matching expenses with the revenues they helped to generate. Since the line costs

were necessary for growth and would help to obtain customers, they would provide benefit

during future periods and their capitalization could be supported under principle-based standards.

Patrone7

Thus, the rules-based nature of the accounting standards is not to blame for the WorldCom

scandal.

Since the standards were not properly applied and the resulting misstatement was highly

material, it follows that the ineffectiveness of WorldComs internal and external controls was a

critical factor in the accounting scandal.

According to The Institute of Internal Auditors, internal auditing is intended to be an

independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an

organization's operations. It helps an organization accomplish its objectives by bringing a

systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management,

control, and governance processes (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2001).

Bernard Ebbers, Chief Executive Officer, told his directors almost nothing and

prevented them from having meaningful contact with other than a few carefully selected and

complicit corporate officers. He carefully scripted and dominated all board meetings. Up until

the time they fired him in April 2002, the board had never met without Ebbers present (Hindery,

2005, p. 89). Due to the efforts of Ebbers, the internal audit committee was unsuccessful in

maintaining an objective mindset, and the internal audit function was ineffective in providing

independent, objective assurance.

The Institute of Internal Auditors also prescribes competency in its rules of conduct as a

required attribute, stating that internal auditors shall engage only in those services for which

they have the necessary knowledge, skills, and experience (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2001).

However, of the four members of WorldComs internal audit committee, none had any

significant financial expertise (Hindery, 2005, p. 90). Moreover, the committee only met

between three and five times a year, and tended to confer for only about an hour when they did

Patrone8

get together (Hindery, 2005, p. 90). The irregularity of its meetings and incompetence of its

members contributed to the internal audit committees failure. It took the internal auditors over

two years to detect the three and a half billion dollars of improperly capitalized expenditures.

Subsequent to the exposure of WorldComs accounting scandal, Steven Brabbs, Director

of International Finance and Control, submitted a memorandum to aid the internal auditors in

their investigation. In the memo, Brabbs indicates that following the close of the first quarter of

2000, financial information for the international division was relayed to senior finance managers

in the United States. An additional journal entry was then added to modify the treatment of line

costs. The adjustment resulted in a nearly $34 million reduction in the line costs for the division.

When the international department inquired as to the basis for the adjustment, the entries were

reported to be under the instruction of Scott Sullivan. Even after several requests by the

international division, no support or explanation for the entry was given by Sullivan

(Eichenwald, 2002). The fact that an inappropriate 34 million dollar adjusting entry was

essentially disregarded speaks volumes to the inadequacy of internal controls for WorldComs

information systems. Not only does Brabbs memo illustrate WorldComs insufficient checks

and balances, but also reveals procedural concerns in that the internal auditors were not informed

of an alleged departure from GAAP.

WorldComs internal controls were ineffective in exposing the financial misstatements

largely because of the companys organizational structure. As was the case with the majority of

large corporations at the time, WorldComs management was designed as a vertical hierarchy.

This highly bureaucratic structure results in a predominantly downward flow of communication.

Inherent in such systems of management is a strong concept of subordination, with centralized

management staff holding the position of power (McCubbrey, 2010). The minimal upward

Patrone9

communication and emphasis on subordination that is typical of such a tall structure generates an

environment that is not conducive to confrontation of executives. This situation was exacerbated

by the inadequate protection afforded to whistleblowers in public companies prior to Section 806

of the Sarbanes Oxley Act.

David Myers, former Controller for WorldCom, met in Sullivans office in January of

2001 with Sullivan and Buford Yates, an accountant. According to testimony given by Myers,

the three agreed to reclassify some of the WorldComs biggest expenses, knowing the company

would not meet analyst expectations for the coming quarter (Knapp, 2010, p. 328). Myers

stated that he didnt think it was the right thing to do, but he had been asked by Sullivan to do it

and was asking Yates to do it (Knapp, 2010, p. 328). Myers situation suggests that the

fraudulent activity at WorldCom was aggravated by the emphasis on chain of command

encouraged by the companys vertical organizational structure. The clear lines of authority

and resulting downward flow of communication encouraged Myers to follow instructions and

made it more difficult for him to confront the Chief Financial Officer to whom he directly reports

(McCubbrey, 2010). Conversely, a flatter organizational hierarchy would have promoted

greater task interdependence with less attention to formal procedures (McCubbrey, 2010). In

such a system Myers would have been less restricted in his regulation of the companys

accounting policies. Additionally, the flatter structure would have deemphasized the chain of

command, creating an environment more conducive to confrontation of Sullivan.

The issues with WorldComs vertical hierarchy are confirmed by correspondence

between Myers and Brabbs. According to Brabbs memo, he was contacted by Myers after

issuing a report to Arthur Andersen notifying the accounting firm of his concerns. Myers,

already immersed in the fraudulent activity, was angry with him for disclosing the issue to the

Patrone10

accounting firm without consulting him. The following quarter, a suggestion was made to

Brabbs that he make the expense transfers at his level, rather than at the high corporate level.

When he refused, he was ordered to do so, and was told this was at Mr. Sullivan's direction. He

continued raising concerns about the matter. But senior finance managers were reluctant to

discuss it, and simply continued to refer back to the fact that the entry had been made at Scott

Sullivan's direct instruction (Eichenwald, 2002). In this circumstance, Brabbs actually

confronted executives in an effort to comply with appropriate accounting standards and mitigate

erroneous procedures. However, WorldComs vertical hierarchy and clearly defined chain of

command trumped virtue and the accurate portrayal of financial data.

As evidenced by Brabbs memo and Myers testimony, WorldComs bureaucratic

structure contributed to employees reluctance and sometimes inability to expose executive

fraud. Moreover, when employees were actually able to challenge lines of authority and

confront executive officers, they were disempowered by the vertical hierarchy. The fraudulent

activity persisted and remained unexposed to stakeholders. Consequently, in order for the

company to avoid fraud and financial misrepresentation, WorldCom relied upon its officers to

act with the utmost integrity.

The responsibilities and role of management in the modern business world is outlined by

two prevailing theories: the stakeholder theory and the stockholder theory. Traditionally,

management has been viewed as an agent for the stockholders (Bowie & Werhane, 2005, p.

21). The manager works for the stockholders and should act in accordance with their objectives.

Since stockholders primary objective is profits, the purpose of management is to increase the

companys stock price. This view is captured by Milton Friedmans stockholder theory, which

states that there is one and only one social responsibility of business- to use its resources and

Patrone11

engage in activities designed to increase its profits as long as it stays within the rules of the

game, which is to say, engages in free and open competition without deception or fraud (Bowie

& Werhane, 2005, p. 21). R. Edward Freemans stakeholder theory defines the duties of

management in a broader context and is gaining acceptance in the modern business world. It

states that management bears a fiduciary relationship to all stakeholders and that the task of the

manager is to balance the competing claims of the various stakeholders (Bowie & Werhane,

2005, p. 25).

Obviously WorldComs executive management was in violation of Friedmans

stockholder theory in that they did not act within the rules of the game (Bowie & Werhane,

2005, p. 21). However, even when disregarding this aspect of stockholder theory, it is clear that

the actions of WorldComs management were in violation of both theories. Although Freeman

defines managements accountability in a broader context, both the stockholder theory and

stakeholder theory indicate that executives have at least some obligation to manage a company in

an effort to earn a return for shareholders. The deceitful accounting methods utilized by

WorldComs executives were an effort to fabricate short-term profits, but in no way were

intended to generate a legitimate return. Furthermore, by committing fraud the executives

exposed WorldCom to potential litigation from creditors and the resulting contingent obligations.

This threatened the companys ability to continue as a going concern and jeopardized the capital

invested by stockholders.

By 2002, eight of the fifteen directors each owned more than a million shares in the

company (Hindery, 2005, p. 89). As a result, much of their wealth was tied up in WorldCom

stock, which would have been steadily declining had it not been for the recurrence of illicit

accounting maneuvers. Fueled by greed, WorldCom executives disregarded the interests of all

Patrone12

of the companys stakeholders in order to mitigate personal losses. In that they violated the

stockholder and stakeholder theories, the actions of WorldCom executives were clearly

unethical. By acting without integrity, these executives exploited the ineffective internal controls

and engaged in fraudulent accounting practices for over two years. However, the ineffective

internal controls and lack of integrity among management are not the only factors contributing to

the financial misrepresentation. The external audit function was also ineffective in detecting and

exposing the improper classifications, making it another causal factor in the sustainment of

WorldComs accounting scandal.

Prior to the establishment of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, the

AICPA governed the audits of public accountants. As of June 1, 2000, the third general standard

of the AICPAs Generally Accepted Auditing Standards was that due professional care be

exercised in the planning and performance of the audit and the preparation of the report

(American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2000). A significant factor in exercising

due professional care is the application of professional skepticism (American Institute of

Certified Public Accountants, 2000). According to the AICPA, the auditor should neither

assume that management is dishonest nor assume unquestioned honesty. In exercising

professional skepticism, the auditor should not be satisfied with less than persuasive evidence

because of a belief that management is honest (American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants, 2000). Arthur Andersen violated this standard in June of 2001. The firm held an

internal brainstorming session to run scenarios as to how WorldCom might deceive the

investment community should it ever choose to do so. One of the scenarios they ran involved the

inappropriate capitalization of costs. But Andersen, deciding that it wasnt likely, simply

discarded the scenario (Hindery, 2005, p. 91).

Patrone13

The firm had a responsibility to act with professional skepticism and diligently perform

the gathering and objective evaluation of evidence (American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants, 2000). Instead, accountants at Andersen disregarded the scenario based on a blind

assessment of its likelihood. The objective of public auditors is to obtain reasonable assurance

that financial statements are free of material misstatements. Auditors design and execute the

audit plan and related substantive procedures with this objective in mind. Obviously accounting

firms must consider economic factors when conducting an audit. Regardless, obtaining

verification that expenses were not being improperly capitalized is relatively inexpensive,

especially through analytical procedures.

This was not the first time Arthur Andersen missed signs of fraudulent activity. When

Brabbs noticed the unsupported adjustment to his divisions line costs, he sent a report to

WorldComs external auditor, Arthur Andersen, providing relevant information and expressing

concern. This report effectively notified Andersen of the accounting issue nearly two years prior

to formal investigations and the restatement of earnings. Nevertheless, in February of 2002

Andersen told WorldComs audit committee that it had reviewed the processes management

was using to account for line costs and found those processes to be effective, and had no

disagreements with them (Partnoy, 2003, p. 370). Yet when the scandal was exposed and

representatives from Arthur Andersen were contacted by WorldCom managers, the firm said

that Sullivans reasoning was contrary to GAAP (Partnoy, 2003, p. 372). So how was it that

Andersen overlooked the inappropriate shift of line costs and the nearly four billion dollar

inflation of income that resulted? One possibility is that the huge fees Andersen was collecting

compromised its independence. The firms aggregate fee from performance of tax, audit, and

Patrone14

consulting services for WorldCom between 1999 and 2001 was over $64 million, which may

have caused some of Andersens accountants to ignore obvious indicators.

Andersen dropped the ball again the following year, failing to expose the accounting

scandal during a due-diligence examination. In May 2001 WorldCom completed an $11.9

billion debt deal, the largest in U.S. history (Partnoy, 2003, p. 369). J.P Morgan and Salomon,

the firms arranging the deal, executed a supposedly extensive due-diligence, as did Arthur

Andersen. Nonetheless, the $771 million of line costs that had been improperly shifted were

either overlooked or disregarded. Failure to detect such a pervasively material financial

misstatement during the due-diligence process for the largest debt deal in U.S. history testifies to

the ineffectiveness of the financial markets control mechanisms and raises questions as to the

intentions of the participating companies.

In comparison with Enron and several other scandals of the time, WorldComs

accounting maneuver was extremely rudimentary. Enron utilized offshore entities and debt

mark-to-market to hide losses, inflating its profits and thereby its stock price. WorldComs

accounting scandal, however, relied directly upon accruals. The company utilized very basic

journal entries to shift expenditures from a period account on the income statement to an asset

account on the balance sheet. So how could financial specialists from the top banks and

accounting firms in the world fail to detect such a simple accounting scheme? It is certainly

possible that corruption existed among WorldCom and the other firms. Several of WorldComs

banks- including J.P. Morgan Chase and Citigroup, Salomons parent- loaned billions of dollars

to WorldCom (Partnoy, 2003, p. 370). The fees associated with the billions in loans would be a

big hit to the banks if WorldCom were to go belly up. This relationship caused the banks to have

a vested interest in WorldComs success. Such an interest decreases the independence of

Patrone15

underwriters and undermines incentive to expose financial misstatements, leading to a highly

ineffective due-diligence process.

In the case of WorldCom, it is clear that the rules-based nature of GAAP is not to blame

for the scandal; the access fees were improperly accounted for relative to both GAAP and the

more principle-based IFRS. Furthermore, the company would have found it easier to support its

fraudulent activity had it been following principle-based standards. By claiming that the line

costs were a cost of obtaining customers, managers could align the improper treatment with the

objective of capitalizing expenditures: matching expenses with the revenues they helped to

generate. In actuality, the scandal was a product of ineffective controls and issues with the

structure and integrity of management. As is the case with most fraudulent activity,

managements lack of integrity was at the core of WorldComs scandal. Fueled by greed,

executives violated basic ethical principles and their managerial responsibilities to shareholders

in order to temporarily inflate profits. The companys highly bureaucratic structure enabled the

executives to control the accounting methods and created barriers to detection and corrective

action. These barriers, coupled with the internal audit teams lack of competence and

independence, contributed to the ineffectiveness of the companys control mechanisms. The last

line of defense against the fraudulent activity and related financial misstatements was the

external audit function, which failed due to the absence of professional skepticism and

independence.

As was mentioned, the ineffectiveness of the internal and external audit functions was

partially due to a lack of independence. It has been argued that independence is the only

justification for the existence of accounting firms that provide outside audits (Moore, Tetlock,

Patrone16

Tanlue, & Bazerman, 2006). In actuality, pure independence in appearance and fact is neither

necessary nor sufficient for an effective audit.

The effectiveness of an audit is a function of two major components: detecting material

misstatements and then actually reporting them. Even if auditors are independent, they may lack

the competence necessary to detect material misstatements. Once a material misstatement has

been detected, however, the likelihood of its exposure and correction is positively correlated with

the auditors independence in fact. However, an auditor need not be emotionally and mentally

detached from a company to act independently. The key attribute of independence is that

auditors not bias their opinion in favor of their client (Nelson, 2006). The assumption of legal

and financial responsibility over damages resulting from the opinion expressed can persuade

auditors to give unbiased opinions, thereby acting as though they are independent. This

accountability is produced by legislation, such as Sarbanes Oxley.

Given the components of an effective audit, it is evident the auditing standards

themselves were not to blame for the WorldCom accounting scandal. The standards for both the

IIA and the AICPA required that auditors be competent, act with due professional care, and

maintain independence. These are the elements that are essential to an effective audit. The issue

with WorldCom was there were no external factors motivating compliance with these standards.

The internal and external auditors failed to maintain independence in fact, and sparse litigation

existed at the time of the scandal to encourage the auditors to act as though they were

independent.

As the accounting profession works toward the convergence of GAAP and IFRS, there is

a preconception that the adoption of new standards will preclude the recurrence of a scandal as

large as WorldComs. However, WorldComs improper capitalization of expenditures did not

Patrone17

point toward problems with the rules-based approach of U.S. GAAP. Rather, the companys

scandal was a result of ineffective control mechanisms and issues with the structure and integrity

of management. While the provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the creation of the Public

Company Accounting Oversight Board do address many of these concerns, they are by no means

justification for the discount of professional skepticism in future engagements.

Patrone18

Appendix A

GAAP Journal Entries for Capital Lease:

At inception of lease:

Telecommunication Lines (asset account)

XX

Lease Payable

XX

To recognize an asset and related liability on the Balance Sheet

Adjusting entry at end of each period:

Interest Expense

XX

Lease Payable

XX

Cash

XX

To amortize the portion of the lease being paid and record incurred interest

Adjusting entry at end of each period:

Depreciation Expense

XX

Accumulated Depreciation

XX

To depreciate the asset for the period

WorldComs Journal Entries*:

At beginning of fiscal year:

Prepaid Line Expenses

XX

Cash

XX

To record the prepayment of fees for leasing telecommunications lines

Adjusting entry at the end of each quarter:

Telecommunications Lines (asset account)

XX

Prepaid Line Expenses

XX

To improperly capitalize the expenses for telecommunications line as an asset

Adjusting entry at the end of each each quarter:

Depreciation Expense

XX

Accumulated Depreciation

XX

To depreciate the fabricated asset

*Note: due to privacy issues related to accounting records, WorldComs account titles and journal entries are projected

Patrone19

Appendix B

GAAP Journal Entries for Operating Lease:

At beginning of fiscal year:

Prepaid Line Expenses

XX

Cash

XX

To record the prepayment of fees for leasing telecommunications lines

Adjusting entry at the end of each quarter:

Line Expenses

XX

Prepaid Line Expenses

XX

To record the incurrment of telecommunications line expenses

WorldComs Journal Entries*:

At beginning of fiscal year:

Prepaid Line Expenses

XX

Cash

XX

To record the prepayment of fees for leasing telecommunications lines

Adjusting entry at the end of each quarter:

Telecommunications Lines (asset account)

XX

Prepaid Line Expenses

XX

To improperly capitalize the expenses for telecommunications line as an asset

Adjusting entry at the end of each each quarter:

Depreciation Expense

XX

Accumulated Depreciation

XX

To depreciate the fabricated asset

*Note: due to privacy issues related to accounting records, WorldComs account titles and journal entries are projected

Patrone20

Works Cited

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2000). AICPA Professional Standards: U.S.

Auditing Standards as of June 1, 2000. New York: Wiley Publishing.

Anastasi, J. (2003). The New Forensics: Investigating Corporate Fraud and the Theft of

Intellectual Property. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Berenson, A. (2003). The Number. New York: Random House.

Bowie, N. E., & Werhane, P. H. (2005). Management Ethics. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Eichenwald, K. (2002, July 15). Auditing Woes At WorldCom Were Noted Two Years Ago.

Retrieved February 4, 2012, from The New York Times:

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/15/business/auditing-woes-at-worldcom-were-notedtwo-years-ago.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

Ernst & Young. (2005). IFRS/US GAAP Comparison. London: William Clowes Ltd.

European Union Center of North Carolina. (2007). The European Union and the Global

Convergence in Accounting Standards. Retrieved February 3, 2012, from European

Union Centers of Excellence:

http://euce.org/assets/doc/business_media/business/Brief0709-accounting-standards.pdf

Hamilton, S., & Micklethwait, A. (2006). Greed and Corporate Failure: the Lessons from

Recent Disasters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hindery, L. (2005). It Takes a CEO. New York: Free Press.

Institute of Internal Auditors. (2001). Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal

Auditing. Altamonte Springs: Institute of Internal Auditors.

Knapp, M. C. (2010). Contemporary Auditing: Real Issues and Cases, 7e. Mason: SouthWestern Cengage Learning.

Lyke, B., & Jickling, M. (202, August 29). WorldCom: The Accounting Scandal. Retrieved

February 4, 2012, from CRS Report for Congress:

http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/13384.pdf

McCubbrey, D. D. (2010, October 6). Flat Versus Tall Organizations. Retrieved February 3,

2012, from Connexions: http://cnx.org/content/m35370/latest/?collection=col11227/latest

Meehan, C. L. (2012). Advantages & Disadvantages of the Vertical Functional Organizational

Structure. Retrieved February 4, 2012, from Demand Media:

http://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-disadvantages-vertical-functionalorganizational-structure-1268.html

Patrone21

Moore, D. A., Tetlock, P. E., Tanlue, L., & Bazerman, M. H. (2006, January). Conflicts of

Interest and the Case of Auditor Independence: Moral Seduction and Strategic Issue

Cycling. Academy of Management, 31(1), pp. 10-29.

Nelson, M. W. (2006, January). Ameliorating Conlficts of Interest in Auditing: Effects of Recent

Reforms on Auditors and Their Clients. Academy of Management, 31(1), pp. 30-42.

Partnoy, F. (2003). Infectious Greed. New York: Times Books.

Spiceland, D., Sepe, J., & Nelson, M. (2011). Intermediate Accounting, 6e. New York: McGrawHill/Irwin.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2002, November 5). United States District Court,

Southern District of New York: First Amended Complaint (Securities Fraud). Retrieved

February 4, 2012, from Securities and Exchange Commission:

http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/comp17829.htm

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Planet Maths 5th - Sample PagesDocument30 paginiPlanet Maths 5th - Sample PagesEdTech Folens48% (29)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Entity-Level Control QuestionnaireDocument28 paginiEntity-Level Control QuestionnaireLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- chp04 CevapDocument3 paginichp04 CevapdbjnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barings - A Case Study For Risk ManagementDocument5 paginiBarings - A Case Study For Risk ManagementGyanendra Mishra100% (1)

- Aicpa - New Cpa Exam ReportDocument119 paginiAicpa - New Cpa Exam ReportLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Welcome Week Schedule 2013Document6 paginiWelcome Week Schedule 2013Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 CA Application PacketDocument10 pagini2014 CA Application PacketLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homework Exercises - 9 AnswersDocument9 paginiHomework Exercises - 9 AnswersLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ten Questions About LeadershipDocument47 paginiTen Questions About LeadershipLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5.campus MapDocument1 pagină5.campus MapLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- And Get $5 in FREE Driving.: Enter As The Promo Code On Your ApplicationDocument2 paginiAnd Get $5 in FREE Driving.: Enter As The Promo Code On Your ApplicationLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Student Payroll CalendarDocument1 pagină2015 Student Payroll CalendarLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- WalmartDocument10 paginiWalmartLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Exam Schedule - Spring 2015Document1 paginăFinal Exam Schedule - Spring 2015Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Exam Schedule - Winter 2015Document1 paginăFinal Exam Schedule - Winter 2015Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seattle University: Academic Calendar 2014-2015 (Summer Quarter - Spring Quarter)Document2 paginiSeattle University: Academic Calendar 2014-2015 (Summer Quarter - Spring Quarter)Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excel FlyerDocument2 paginiExcel FlyerLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 CA Application PacketDocument10 pagini2015 CA Application PacketLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seattle University: Academic Calendar 2014-2015 (Summer Quarter - Spring Quarter)Document2 paginiSeattle University: Academic Calendar 2014-2015 (Summer Quarter - Spring Quarter)Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- PS Leadership Cruise FlyerDocument1 paginăPS Leadership Cruise FlyerLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- GradAppEDU13 14pdfDocument16 paginiGradAppEDU13 14pdfLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAQ - Albers Excel CertificationDocument2 paginiFAQ - Albers Excel CertificationLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5.campus MapDocument1 pagină5.campus MapLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14SQ Final ScheduleDocument1 pagină14SQ Final ScheduleLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Su Illiad Article Download: Ill@Seattleu - EduDocument15 paginiSu Illiad Article Download: Ill@Seattleu - EduLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- SUmmer Student Course Guide 051713Document4 paginiSUmmer Student Course Guide 051713Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics, GovernanceDocument11 paginiEthics, GovernanceLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Derivatives CaseDocument10 paginiDerivatives CaseLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA Supplemental Application 2012-13Document2 paginiRA Supplemental Application 2012-13Lương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ten Questions About LeadershipDocument47 paginiTen Questions About LeadershipLương Thế CườngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Southeast Asian Fabrics and AttireDocument5 paginiSoutheast Asian Fabrics and AttireShmaira Ghulam RejanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Implementation of 7s Framenwork On RestuDocument36 paginiImplementation of 7s Framenwork On RestuMuhammad AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15 Melodic Uses of Non-Chord TonesDocument3 pagini15 Melodic Uses of Non-Chord TonesonlymusicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIDA Deconstruction of Surf Excel AdDocument6 paginiAIDA Deconstruction of Surf Excel AdRoop50% (2)

- Commercial CrimesDocument3 paginiCommercial CrimesHo Wen HuiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pace, ART 102, Week 6, Etruscan, Roman Arch. & SculpDocument36 paginiPace, ART 102, Week 6, Etruscan, Roman Arch. & SculpJason ByrdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gothic Revival ArchitectureDocument19 paginiGothic Revival ArchitectureAlexandra Maria NeaguÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 2 Foundations of CurriculumDocument20 paginiUnit 2 Foundations of CurriculumKainat BatoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radiopharmaceutical Production: History of Cyclotrons The Early Years at BerkeleyDocument31 paginiRadiopharmaceutical Production: History of Cyclotrons The Early Years at BerkeleyNguyễnKhươngDuyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Darkness Points Reminder 2Document2 paginiDarkness Points Reminder 2Tata YoyoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ubi Jus Ibi RemediumDocument9 paginiUbi Jus Ibi RemediumUtkarsh JaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ang Tibay Vs CADocument2 paginiAng Tibay Vs CAEarl LarroderÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Paper-2) 20th Century Indian Writing: Saadat Hasan Manto: Toba Tek SinghDocument18 pagini(Paper-2) 20th Century Indian Writing: Saadat Hasan Manto: Toba Tek SinghApexa Kerai67% (3)

- Donna Claire B. Cañeza: Central Bicol State University of AgricultureDocument8 paginiDonna Claire B. Cañeza: Central Bicol State University of AgricultureDanavie AbergosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sta. Lucia National High School: Republic of The Philippines Region III-Central LuzonDocument7 paginiSta. Lucia National High School: Republic of The Philippines Region III-Central LuzonLee Charm SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excellent Inverters Operation Manual: We Are Your Excellent ChoiceDocument71 paginiExcellent Inverters Operation Manual: We Are Your Excellent ChoicephaPu4cuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filipino HousesDocument4 paginiFilipino HousesjackÎncă nu există evaluări

- ThesisDocument58 paginiThesisTirtha Roy BiswasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Consequences of UnemploymentDocument3 paginiSocial Consequences of UnemploymentvillafuerteviÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Thi Hoc Ki 2 Lop 3 Mon Tieng Anh Co File Nghe So 1Document3 paginiDe Thi Hoc Ki 2 Lop 3 Mon Tieng Anh Co File Nghe So 1huong ngo theÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of Courts in Granting Bails and Bail Reforms: TH THDocument1 paginăRole of Courts in Granting Bails and Bail Reforms: TH THSamarth VikramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bug Tracking System AbstractDocument3 paginiBug Tracking System AbstractTelika Ramu86% (7)

- India Marine Insurance Act 1963Document21 paginiIndia Marine Insurance Act 1963Aman GroverÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Global StudyDocument57 paginiA Global StudyRoynal PasaribuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Navamsa Karma and GodDocument9 paginiNavamsa Karma and GodVisti Larsen50% (2)

- Vrushalirhatwal (14 0)Document5 paginiVrushalirhatwal (14 0)GuruRakshithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Afia Rasheed Khan V. Mazharuddin Ali KhanDocument6 paginiAfia Rasheed Khan V. Mazharuddin Ali KhanAbhay GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Personalization, Engagement and Trust in Online CommunitiesDocument17 paginiThe Role of Personalization, Engagement and Trust in Online CommunitiesAbiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appellees Brief CIVILDocument7 paginiAppellees Brief CIVILBenBulacÎncă nu există evaluări