Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

GFL 587 Trade Vs Aid

Încărcat de

avaniTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

GFL 587 Trade Vs Aid

Încărcat de

avaniDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Geo file

Online

January 2009

587

Callum Rae

Trade Versus Aid

Introduction

Since the 1950s we have been familiar

with the concept of the third world

or developing world, a recognition

of the gross inequalities that exist

between the worlds nations. This

difference between countries

is sometimes referred to as the

Development Gap. Todays LEDCs

actually make up over two-thirds of

the world, in terms of both area and

population, consisting of the majority

of Africa, Latin America and much

of Asia. These countries are almost

all former colonies of the European

powers, and are characteristically

very poor in economic terms when

compared to the West. A typical

LEDC has little in the way of

industry or technological advances,

with the majority of production being

low-level agriculture. Many of these

countries also suffer from chronic

poverty and related issues of famine,

disease and violence.

For the last 60 years efforts towards

the development of the impoverished

world have been characterised by

two key approaches, with highly

debateable results in each case. The

first is the concept of using trade

to promote economic growth. The

second is the provision of aid by the

wealthy West to the poor South. This

Geofile will look at both approaches,

how they have been applied and what

effect they have had upon the third

world.

Trade and economic growth

When the concept of the developing

world gained recognition in the 1950s

and 1960s, the principal approach

to improving conditions was to find

ways for those countries to generate

high levels of economic growth.

Economic growth can be defined as

the increase in output of goods and

services that a country produces over

a period of time, which can be seen

by an increase in GDP. Economic

growth is considered essential to the

development of a country, increasing

the amount of wealth being generated

in the country, and in theory that

extra wealth allows for the living

conditions of the countrys population

to improve.

In the 1950s and 1960s the approach

taken was that developing countries

needed to increase economic growth

via a process of modernisation.

Essentially this consisted of two key

elements, the first being an increase

in international trade and the

second being a process of intensive

industrialisation to help provide

goods for export. In effect, developing

Figure 1: World map showing percentage of population living below poverty line

Key

>50%

3050%

<30%

No data

Source: CIA World Factbook, 2008

Geofile Online Nelson Thornes 2009

GeoFile Series 27 Issue 2

countries were being encouraged

to use the same kind of model that

Western countries had adopted in the

past, a capitalist system of trading

coupled with a powerful industrial

sector. The theory was that since it

had worked for the West, it should

work for the rest of the world too.

Even though it was clear by the end

of the 1960s that this model was

not having the desired impact upon

economic growth, the basic concept

of using trade to promote economic

growth to improve a countrys

conditions has remained at the core

of much of development thinking

to this day. This is partly because

the attitude that the West did it, so

can they has remained strong with

certain international groups, but

also because economic growth is

still seen as highly desirable. This is

true even for development thinkers

who are less concerned with simply

economic results. As the majority of

any population is seen to be involved

with the local market in one way or

another, the generation of economic

growth is seen to have a trickledown effect, providing extra money

and resources. This extra wealth

should ideally allow for new industry

to begin and for more goods to be

produced, allowing for more trade

and further economic growth. The

January 2009 no.587 Trade Versus Aid

adoption of Western-style capitalism

is also seen to be beneficial politically,

as capitalism tends to foster

democratic institutions, allowing

for the population to be better

represented and for fairer conditions

to be established.

These ideas about trade and

economic growth have become closely

associated with a concept known

as neoliberalism. Neoliberalism

is an idea which became popular

during the 1970s as an answer to

problems with the global market

at that time, and since then has

dominated ideas about international

development, right up to the present

day. Neoliberalism is basically the

idea that free trade is essential for

economic growth, so markets should

be allowed to be as open as possible,

with no restrictions. The fewer

restrictions there are, the more trade

can take place, the more growth and

benefits there will be. Neoliberalists

tend to dislike governments and

the state, and believe that their

ability to make rules should be kept

to a minimum, so that they do not

interfere with markets and trading.

Key international organisations

such as the World Bank and the

International Monetary Fund (IMF),

as well as powerful Western countries

like the USA and the UK, have been

strong supporters of neoliberal ideas.

As a result of this strong international

support for neoliberalism, many

developing countries have been

encouraged to reduce the power of

their governments and to allow for

as much free international trade as

possible. This was especially the

case in Latin America during the

1980s. However neoliberalism and

trade-led growth models have also

received a high degree of criticism,

and their effectiveness is increasingly

challenged.

Criticisms of trade-led

growth

Despite the vehement support of

various institutions like the World

Bank, IMF and the World Trade

Organisation for systems of trade-led

growth, this approach is subject to

numerous criticisms. There have,

after all, been efforts towards trade-led

growth for the last 60 years, and yet

the majority of developing countries

still remain very poor in comparison

to the West. The development gap

has in some cases widened, as rich

countries have become richer and

Geofile Online Nelson Thornes 2009

Figure 2: The World Trade Centre in

Seoul, South Korea.

poorer countries have declined

under the weight of increasing

socioeconomic problems. So the

approach is seen to be flawed.

In their defence, neoliberalists

often point to a small group of

countries which have experienced

significant economic success as a

result of trade, the so-called Asian

Tigers: Taiwan, South Korea,

Hong Kong and Singapore. These

countries were all very poor in the

1960s, but have since experienced

incredible rates of economic growth

and industrialisation thanks to the

opening up of their markets and

free international trade. As such,

neoliberalists claim that their theory

works, but only if properly applied,

suggesting that developing countries

remain poor because they are not

implementing the trade model

correctly. However this view is often

challenged; the economic miracle

of the Asian Tigers is attributed

to factors other than simply trade,

such as protectionist methods by

their governments, a distinctly antineoliberalist approach.

One strong criticism of using free

trade is that LEDCs cannot be truly

competitive in the global market

because of the disparity between the

wealth of the super-rich Western

countries and the majority of

developing countries. Developing

countries lack the ability to invest

in the same level of industrial

production and technological skill as

Western countries, and so struggle to

compete. A related issue is that the

majority of developing counties rely

on agricultural exports, and indeed

have been encouraged to do so in

the past. The problem is that the

price of agricultural goods has been

steadily decreasing for the last few

decades and has only recently begun

to level out, so there is little profit to

be made in this sector. This problem

is further exacerbated by Western

countries seeking to protect the

interests of their own farmers. A good

example of this is the EU Common

Agricultural Policy. Countries also

leave themselves open to exploitation

by allowing totally free trade and

restricting the strength of their

governments, as countries with high

levels of natural resources such as

oil or diamonds frequently become

targeted by wealthy countries or

transnational corporations.

Another issue with trade is that it

is often very difficult to ensure that

the growth that is generated has the

desired trickle-down effect and

benefits the majority of the people

who live in the country. Programmes

of free trade and industrialisation

often fail to generate the pro-poor

growth that is desired, and instead

end up benefiting only a certain few

elite groups of a society. For example,

in countries such as Brazil and

Mexico, there is a continuing problem

that people with formal employment

in the big corporations do very well

financially and have good social

security, but only make up a fraction

of the number of people living in the

country. Instead of helping the poor,

the gap between the poor and the rich

within the country seems to widen.

Given these limitations, one might

ask why so many developing countries

still pursue policies of free trade

and reduced state intervention. The

answer in some cases is that they do

have little choice. Many of the worlds

poorest countries suffer from a high

level of debt that they owe the World

Bank, which puts them in a difficult

position. In exchange for further

financial help, the World Bank and

the IMF often enter agreements with

indebted countries where the country

must implement recommended

changes. These are often referred to as

structural adjustment programmes

(SAPs), although there are variations

on this kind of policy. These

programmes are strongly based on

the neoliberal attitudes of the World

Bank and IMF, encouraging reduced

state control and increased exports

and trade. Developing countries have

little choice in the matter if they are

to continue to borrow money.

One final thing to consider is the

question of whether trade and

economic growth can really be

enough to develop a country? Whilst

neoliberalists and others argue that

it is, others challenge this theory.

January 2009 no.587 Trade Versus Aid

They question whether trade and

wealth alone are enough to deal with

problems like famine, war, corruption

and health epidemics such as HIV/

AIDS, and whether significant

economic growth will ever take place

with these kinds of problems holding

a country back.

Figure 3: ActionAid project: women

in this Indian village now market their

own produce.

Aid

Like the concept of trade, the

approach of using aid to help

LEDCs develop has been around

since the 1950s. In many ways it

can be seen to have started with

the United States Marshall Plan

(194851), a programme designed

to provide money to help western

European countries which had been

economically devastated by the

Second World War. The concept was

broadened to create a means by which

developing countries could be helped

to improve their economic situation.

There are three main systems by

which aid is distributed:

1. Bilateral aid is where aid is given

directly by the government of

a donor country to a recipient

country.

2. Multilateral aid is given by a

donor country to an international

organisation, such as the

World Bank or the European

Development Fund, who then use

the money in programmes to assist

developing countries.

3. NGOs (non-governmental

organisations) also provide and

distribute aid in a variety of

different ways. Some NGOs are

charities, which raise money to

use for aid programmes, others

are more involved with the

management of aid projects,

ensuring that aid is effectively

used and distributed. The number

of NGOs has increased rapidly

since the 1990s.

Aid can involve transfers of finance,

goods or technical assistance (which

makes up around half of all bilateral

aid). Even though initially aid

was mostly focused on economic

concerns, aimed at building up

infrastructure and industry, over

time it has diversified as a concept

to include many different forms.

For example, the Cold War led to

high levels of military aid being used

by the superpowers to keep certain

countries on their side and to expand

their spheres of influence. Another

common use of aid is as a source of

debt relief.

Geofile Online Nelson Thornes 2009

Courtesy of ActionAid

Given that aid is such a wide-ranging

concept, it is useful to try and divide

it into different categories:

Short-term initiatives, such as

disaster relief aid, which has a

specific objective to help a country

recover from a particular event

and to save lives. For example the

World Food Programme provided

food aid to more than 1.3million

people in the wake of the Indian

Ocean tsunami of December 2004.

Alternatively aid is often used as

part of long-term development

projects, with particular goals

being worked toward over time.

These can take many different

forms, from investing in industry

or agriculture, to building schools

and hospitals, to supporting the

countrys budget.

Some aid is seen as being

top-down, meaning that it is

coordinated by a senior body like

a government or international

organisation, who are at the

top. These are typically capitalintensive schemes aimed at

improving the country as a whole.

For example, the Akosombo

Dam in Ghana was constructed

by the government with the help

of foreign aid as part of a plan to

improve electricity production and

industry.

Other forms of aid are described

as bottom-up, referring to

NGOs and other organisations

who work with communities

and local groups to improve

their conditions. For example,

Actionaid is a charity NGO which

invests in individual villages.

These are sometimes called

grassroots initiatives. They often

involve a lot more dialogue with

people receiving the aid than topdown methods.

One of the most important ways

that aid differs from trade is in its

diversity. As you can see there are

many different kinds of aid and

they all have different objectives.

Like trade, aid can be to help with

economic development, but it can also

be targeted at many other concerns

such as basic human needs, social

development, or environmental

conservation. This can be seen as one

of the greatest strengths of using aid

within a development framework.

The problems with aid

Aid is not without its drawbacks

and difficulties. By the 1990s some

observers began to claim that

an aid crisis had emerged. The

achievements of aid programmes

were increasingly questioned, as

the conditions of the majority

of LEDCs did not seem to be

improving. Popular support for aid

was dwindling as a result and many

countries were cutting back on their

aid expenditure. Since the end of the

Cold War, not only has military aid to

developing countries been reduced,

but a substantial amount of bilateral

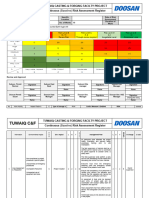

Figure 4: Net overseas development aid in 2005, as a percentage of GNI

Country

Sweden

Norway

Netherlands

Austria

France

UK

Germany

Spain

United States

ODA, as % of GNI

0.94

0.94

0.82

0.52

0.47

0.47

0.36

0.27

0.22

January 2009 no.587 Trade Versus Aid

financial aid has been cut too. Many

donor countries lost the political will

to maintain aid programmes. The

current figures on aid expenditure for

members of the OECD (a group of the

30 highest income countries in the

world) remain far below the amount

of aid that is regarded as minimum by

the UN. The UN suggests that high

income countries should give 0.7%

of their gross national income in aid;

however, as Figure 4 shows, only a

handful of countries actually commit

to this. It is estimated that aid figures

for 2006 would have been $280 billion

higher if countries had committed to

the 0.7% figure.

Perceived problems with aid as

a concept are many. One of the

concerns is that aid money frequently

does not get to where it is needed

or that it is used ineffectively. This

can be due to corruption in the

governments and institutions of

developing countries, who use the

money for themselves. It can just as

easily be an unintended outcome, as

sometimes it is simply too difficult

to use aid money effectively, due to a

lack of resources or infrastructure. For

example it is not easy to invest money

in schools or hospitals when those

places have no roads or power, as is

the case in many parts of rural Africa.

Perhaps the most significant issue

with aid is that it is often subject

to conditionality. Aid is not

actually free, but comes at a price,

as a developing country must agree

to certain conditions in order to

receive aid. These conditions often

undermine the effectiveness of aid

programmes, or even lead to more

problems for the country receiving

aid. One of the most common forms

of conditionality is what is called tied

aid. Tied aid is when bilateral aid is

given to a developing country, on the

condition that this money must be

spent on goods or services that come

from the donor country. A famous

example of this occurred in 1991

when the UK gave 234 million in aid

to Malaysia towards the construction

of a hydroelectric dam. This was later

revealed to be tied to an arms deal

that Malaysia made with the UK to

buy a substantial number of weapons.

Another significant occurrence of

conditional aid involves the structural

adjustment programmes forced onto

developing countries by the World

Bank and IMF, which we discussed

earlier. Developing countries must

agree to the conditions of structural

Geofile Online Nelson Thornes 2009

adjustment if they are to receive

much-needed financial aid from these

institutions.

Despite these problems and

criticisms, some people argue that

there is a new movement with regard

to aid. Since the end of the Cold War

there has been a dramatic rise in

the number of conflicts in the third

world, and aid is seen as necessary

to help deal with the increase in

refugees and economic problems that

have been caused. Some also claim

that there is a new shift towards

development partnership, where

recipient countries will have much

more of a say in the aid they receive

and how it is used. The IMF has

introduced what it calls Poverty

Strategy Reduction Papers (PRSPs),

which are meant to replace SAPs and

involve a much greater dialogue with

the countries involved. However,

these have been criticised as being

just as bad as SAPs, as PRSPs still

focus on a neoliberal agenda. Also

developing countries have little choice

in whether they agree, as adopting a

PRSP is required in order to qualify

for the IMF and World Banks HIPC

programme, which provides debt

relief. So the future of aid and how

it will be carried out remains an

uncertain prospect.

trade by themselves are enough to

make a significant difference to the

developing world, but must be used as

part of a much greater framework of

international development.

Websites

http://www.worldbank.org World

Bank website.

http://www.actionaid.org.uk website

of a UK Aid NGO.

http://www.mdgmonitor.org an

interactive website allows you to

explore the progress of the UNs

Millennium Development Goals

worldwide.

http://real-lives.en.softonic.com

allows you to download Real Lives,

a free educational game that simulates

the conditions people experience

around the world.

Conclusion

It can be seen that aid and trade

policies both come with their

problems and historically have

been limited in what they have

accomplished. This is not to say

that use of either approach has been

an outright failure, as there are

numerous success stories, but both

can be seen to have failed in many

other cases as well. Both could be

said to require careful changes and

monitoring if they are going to have

a chance of creating success stories. It

can also be said that neither aid nor

Focus Questions

1. Choose either trade or aid. Analyse the strengths and weaknesses of this

development concept.

2. Examine the different ways aid is distributed and decide which

methods you think work best, explaining your reasons.

3. What is neoliberalism? What have been the positive and negative

effects of using neoliberal policies?

4. What is poverty? Is it purely to do with income or are other factors

important?

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Aditipatra HR Sem7th AssignmentDocument2 paginiAditipatra HR Sem7th AssignmentADITI PATRAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ow To AVE Lobalization ROM TS HeerleadersDocument33 paginiOw To AVE Lobalization ROM TS HeerleadersKarin PotterÎncă nu există evaluări

- MB0037Document8 paginiMB0037Venu GopalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Global Contexts: Aims of This ChapterDocument21 pagini4 Global Contexts: Aims of This ChapterstephjmccÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Muhammad Yunus) Creating A World Without Poverty - (Z Lib - Org) Páginas 35 72Document38 pagini(Muhammad Yunus) Creating A World Without Poverty - (Z Lib - Org) Páginas 35 72Raquel FranciscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Integration in Pursuit of Sustainable Human Development: Analytical PerspectivesDocument25 paginiGlobal Integration in Pursuit of Sustainable Human Development: Analytical PerspectivesCarmel PuertollanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examine The Relevance of The Modernization TheoryDocument7 paginiExamine The Relevance of The Modernization TheoryShonhiwa NokuthulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Master of Business Administration-MBA Semester 4cDocument15 paginiMaster of Business Administration-MBA Semester 4cChitra KotihÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Two Faces of GlobalizationDocument4 paginiThe Two Faces of GlobalizationSunail HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization Is An Inevitable Pdohenomenon in Human History ThatDocument2 paginiGlobalization Is An Inevitable Pdohenomenon in Human History Thatbenazi22Încă nu există evaluări

- GlobalizationDocument3 paginiGlobalizationsameer shaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stiglitz Glob and GrowthDocument20 paginiStiglitz Glob and GrowthAngelica MansillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BY Registration Date Submitted To: Rabail Awan 3361 15 December 2010 Sir, Qazi SalmanDocument9 paginiBY Registration Date Submitted To: Rabail Awan 3361 15 December 2010 Sir, Qazi Salmankanwal1234Încă nu există evaluări

- How To Save GlobalizationDocument34 paginiHow To Save GlobalizationkevinfromexoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization and Its DiscontentsDocument2 paginiGlobalization and Its DiscontentsrizkielimbongÎncă nu există evaluări

- The West and The Rest Free Trade Imperialism (1850-1914)Document4 paginiThe West and The Rest Free Trade Imperialism (1850-1914)gollum_lauraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Business Environment Strategy D2Document10 paginiGlobal Business Environment Strategy D2DAVIDÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Trade and BusinessDocument8 paginiInternational Trade and BusinesssyyleeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yunus PDFDocument19 paginiYunus PDFArya Vidya UtamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization: by Tina RosenbergDocument14 paginiGlobalization: by Tina RosenbergnalamihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global PoliticsDocument3 paginiGlobal PoliticsANTONIA ANGEL ARISTIZABALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structural Adjustment - A Major Cause of PovertyDocument10 paginiStructural Adjustment - A Major Cause of PovertyBert M DronaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization and Its Impacts On PAK ECODocument23 paginiGlobalization and Its Impacts On PAK ECOwaqasidrees393Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction and History of Globalization: Charles Taze RussellDocument4 paginiIntroduction and History of Globalization: Charles Taze RussellGhulamKibriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Business Environment and Foreign Exchange EconomicsDocument3 paginiInternational Business Environment and Foreign Exchange EconomicsVivek SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contemporary World Module 3Document6 paginiContemporary World Module 3Vina Marie OrbeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Global Is at IonDocument18 paginiImpact of Global Is at IontalwarshriyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Difference Between Developed and Developing CountriesDocument8 paginiDifference Between Developed and Developing Countriesnabeeha_ciit100% (4)

- The Future of Economic ConvergenceDocument50 paginiThe Future of Economic ConvergenceScott N. ChinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rostow's Theory: Examples of The Different Stages of The Rostow ModelDocument19 paginiRostow's Theory: Examples of The Different Stages of The Rostow ModelShahriar HasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neo Liberalism StarDocument5 paginiNeo Liberalism StarLisbonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vision VAM 2020 (Essay) Reverse GlobalizationDocument8 paginiVision VAM 2020 (Essay) Reverse GlobalizationGaurang Pratap SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q1. Write A Note On Globalization.: 1. Trade: Developing Countries As A Whole Have Increased Their Share of World TradeDocument6 paginiQ1. Write A Note On Globalization.: 1. Trade: Developing Countries As A Whole Have Increased Their Share of World TradeYogesh MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization CoverageDocument43 paginiGlobalization CoverageJennifer Maria Suzanne JuanerioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Issues Brief - Globalization - A Brief OverviewDocument12 paginiIssues Brief - Globalization - A Brief OverviewVon Rother Celoso DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization: Historical DevelopmentDocument9 paginiGlobalization: Historical DevelopmentManisha TomarÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Does Globalization MeanDocument6 paginiWhat Does Globalization Meangervel2102Încă nu există evaluări

- States of Disarray: The Social Effects of GlobalizationDocument13 paginiStates of Disarray: The Social Effects of GlobalizationUnited Nations Research Institute for Social DevelopmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comments On Goldberg and Reed July 2023Document4 paginiComments On Goldberg and Reed July 2023Carding Amazon TrustedÎncă nu există evaluări

- FEER Final Edited by Restall and BhagwatiDocument8 paginiFEER Final Edited by Restall and BhagwatiDmitry SergeevÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Survey of Development TheoriesDocument2 paginiA Survey of Development Theoriesbsma.tenoriorcÎncă nu există evaluări

- AssignmentDocument3 paginiAssignmentRicha ILSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grp04 S03 - Bhagwati Ch05Document4 paginiGrp04 S03 - Bhagwati Ch05api-3695734Încă nu există evaluări

- 23 Things They Don't Tell You about CapitalismDe la Everand23 Things They Don't Tell You about CapitalismEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (21)

- Breakthrough Elfren S. Cruz: Washington Post in The US and The London Times, Guardian, Financial Times in The UKDocument6 paginiBreakthrough Elfren S. Cruz: Washington Post in The US and The London Times, Guardian, Financial Times in The UKKay Tracey A. Urbiztondo100% (1)

- Handout 4 The Pros and Cons of GlobalizationDocument9 paginiHandout 4 The Pros and Cons of GlobalizationSYMONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Issues in Economic DevelopmentDocument4 paginiIssues in Economic DevelopmentMôhámmąd AàmèrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization in The World EconomyDocument6 paginiGlobalization in The World EconomyRonaldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Croitoru Adrian-Marian Rise An Ii The Challenge of GlobalisationDocument3 paginiCroitoru Adrian-Marian Rise An Ii The Challenge of Globalisationflory82floryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 4:: Science For Sustainable DevelopmentDocument27 paginiGroup 4:: Science For Sustainable DevelopmentSheina Elijah PenetranteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Globalization TodayDocument2 paginiEconomic Globalization TodayAllie LinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islam and Economic GrowthDocument6 paginiIslam and Economic GrowthpathanthegeniusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does Globalization Help or Hurt (Sci Am 2006)Document3 paginiDoes Globalization Help or Hurt (Sci Am 2006)FRANCISCO JAVIER ESTRADA ORD��EZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angielica N. Rabago Ii-Bstm Activity No. 1Document4 paginiAngielica N. Rabago Ii-Bstm Activity No. 1Clerk Janly R FacunlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Plight of The Poor: The US Must Increase Development AidDocument6 paginiThe Plight of The Poor: The US Must Increase Development AidMelissa NewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strong Globalisation ThesisDocument6 paginiStrong Globalisation ThesisBuyCustomPapersOnlineChicago100% (2)

- BIG A2 Global Development RevisionDocument19 paginiBIG A2 Global Development RevisionAhhh HahahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization - A Brief OverviewDocument8 paginiGlobalization - A Brief OverviewfbonciuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Man and SupermanDocument4 paginiMan and SupermanSrestha KarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kornet ''Contracting in China''Document31 paginiKornet ''Contracting in China''Javier Mauricio Rodriguez OlmosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incident Summary Report: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 8535 Northlake BLVD West Palm Beach, FLDocument5 paginiIncident Summary Report: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 8535 Northlake BLVD West Palm Beach, FLAlexandra RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loss of ReputationDocument6 paginiLoss of ReputationHanis AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay IiDocument44 paginiEssay IimajunyldaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Components of Culture: Reported By: Kristavilla C. OlavianoDocument13 paginiComponents of Culture: Reported By: Kristavilla C. OlavianoKristavilla OlavianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interaction AnalysisDocument2 paginiInteraction Analysisapi-302499446Încă nu există evaluări

- Buslaw08-Mutual Assent and Defective AgreementDocument27 paginiBuslaw08-Mutual Assent and Defective AgreementThalia SandersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simple Red and Beige Vintage Illustration History Report PresentationDocument16 paginiSimple Red and Beige Vintage Illustration History Report Presentationangelicasuzane.larcenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pacta Sunt Servanda - Agreements Must Be KeptDocument3 paginiPacta Sunt Servanda - Agreements Must Be KeptByron Jon TulodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance Appraisal Is Also Considered As A "Process of Establishing or Judging The ValueDocument9 paginiPerformance Appraisal Is Also Considered As A "Process of Establishing or Judging The ValueKhondaker Fahad JohnyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jihad Brown Metaphysical Dimensions Tabah Essay enDocument31 paginiJihad Brown Metaphysical Dimensions Tabah Essay ensalleyyeÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES of The Phil Vs Dorico Et Al PDFDocument8 paginiPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES of The Phil Vs Dorico Et Al PDFYsabel MacatangayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grup 2Document6 paginiGrup 2FatihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urgent Updated Notice and Actions 4/10: South Bronx NEWS! Casa Atabex Ache Asked To Vacate Their Space!Document1 paginăUrgent Updated Notice and Actions 4/10: South Bronx NEWS! Casa Atabex Ache Asked To Vacate Their Space!Casa Atabex AchéÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACTIVITY # 1: The Mini-IPIP (International Personality Item Pool Representation of The NEO PI-R) Scale (20 Points)Document6 paginiACTIVITY # 1: The Mini-IPIP (International Personality Item Pool Representation of The NEO PI-R) Scale (20 Points)cheysser CueraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of The Applied Social Sciences ProcessesDocument6 paginiThe Effects of The Applied Social Sciences ProcessesEdgar Espinosa II0% (1)

- Essentials of CrimeDocument4 paginiEssentials of CrimerajesgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conciencia Emoción PDFDocument22 paginiConciencia Emoción PDFdallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Surprising Way To A Stronger Marriage - How The Power of One Changes EverythingDocument34 paginiThe Surprising Way To A Stronger Marriage - How The Power of One Changes EverythingSamantaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Four Stages of Psychological Safety Behavioral GuideDocument47 paginiThe Four Stages of Psychological Safety Behavioral GuideDebora Amado100% (1)

- PM ProjectDocument13 paginiPM ProjectYaswanth R K SurapureddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Intentionality Without Subject or ObjDocument25 paginiAn Intentionality Without Subject or ObjHua SykeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assertive, Aggressive and Passive BehaviourDocument5 paginiAssertive, Aggressive and Passive BehaviourJohn Lordave Javier100% (1)

- Special Law VandalismDocument3 paginiSpecial Law VandalismmaechmÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Precariedade de LiberdadeDocument35 paginiA Precariedade de LiberdadeSuzana CorrêaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mooting Manual: What Does Mooting Involve?Document4 paginiMooting Manual: What Does Mooting Involve?Amarjeet RanjanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ngwa Joseph Neba: AcknowledgementsDocument8 paginiNgwa Joseph Neba: AcknowledgementsLuma WilliamÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA 18 (Well Bore Using Excavator Mounted Earth Auger Drill) 2Document8 paginiRA 18 (Well Bore Using Excavator Mounted Earth Auger Drill) 2abdulthahseen007Încă nu există evaluări

- Part of Essay: Body Paragraph, Paragraphing, Unity and CoherenceDocument3 paginiPart of Essay: Body Paragraph, Paragraphing, Unity and CoherenceSari IchtiariÎncă nu există evaluări