Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Conclusion - Maharashtra Tarriff Story

Încărcat de

Mandar Vaman SatheDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Conclusion - Maharashtra Tarriff Story

Încărcat de

Mandar Vaman SatheDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

11.

Conclusions: Looking

Back to Look Ahead

Tariff is an important tool of governance

of public services. It can bring in not only

economic but social and environmental

changes in the way water resources are

managed by the service provider as well as the

service users. Water provides a unique case for

regulation through tariff due to the plurality of

values attached to water as a resource. Tariff

system cannot be designed by treating water as

a pure commodity. It needs to integrate social,

political, environmental, cultural, aesthetic and

recreational values. There is a tendency to

segregate and isolate these values from one

another to allow better management of water.

For example, it is often said that tariff should be

determined purely based on economic concerns

by isolating it from other concerns. Social and

other non-economic values should be

addressed by some other policy instruments

such as allocation criteria or subsidy regime.

But there are reasons why such a segregated and

dis-integrated approach will not be useful in

long-term. The reasons for this can be found in

the understanding that water is totally different

than any other public service. This poses a great

challenge in managing and governing water.

The complexity around the multiplicity of

values attached to water is one of the major

challenges in water governance. Apart from

this, water as a mere physical resource also

poses serious challenges. It is a purely natural

resource managed through artificial man-made

structures. We cannot produce water. Water

availability is highly variable, both temporally

and spatially. It is fluid in nature and has a

natural gravitation-based flow. It evaporates

and seeps into the ground. It is highly connected

38

Maharashtra Water Tariff Story

to other ecosystem components. It is a product

of ecosystem services. It is so strongly

embedded into the complex of web of

ecosystem that more we want to manage it

artificially more damage can happen to the

ecosystem services. Overall it can be said that

unlike other infrastructure services and

products water is a highly complex and difficult

to manage. It needs to be handled with extreme

care. Tariff being an important aspect of water

governance a similar care is needed while

designing the tariff system by giving due

consideration to all its facets.

The experience of the tariff determination

process in Maharashtra initiated by MWRRA

showcases the complexities involved in

developing a tariff system. This experience

gains importance due to the multiplicity of

issues and concerns that could be discussed and

considered in designing the tariff system. It

brings into focus the complexities, peculiarities

and challenges of water governance discussed

in the previous paragraphs. These broader

substantive issues came into picture during the

consultation process mainly because of the

participatory nature of the tariff process and

because the process was focussed on bulk

water instead of retail water supply. Bulk

water governance involves the water system

right from its source (such as the storage dam)

to its distribution network. Hence, it brings the

sense of resource unlike the sense of service

that dominates the discussion on retail water

tariff. Bulk water also brings into light the

dynamics between the major categories of

water users (industry, agriculture, domestic)

which also represents the major economic

sectors competing for the limited water

resource. It is in this context of broader issues of

water governance that the tariff process by

MWRRA needs to be seen.

The tariff determination process initiated

by MWRRA, being the first of its kind in India,

provides vital lessons in this regard. The

attempt in this report has been to look back to

look ahead. Thus, the analysis of the past

process and substantive issues around the tariff

process is undertaken in a critical way, not to

just keep indulging and digging out past

failures but to move on to develop a new vision

for the future. Thus, drawing constructive

lessons from the past is important.

There are several lessons from the

procedural and substantive analysis of the tariff

process. Procedural robustness has been

considered as one of the important dimension

of the legitimacy of independent regulators,

especially when such non-majoritarian

institutions are delegated with function of

policy making on issues pertaining to

distribution of costs and benefits (Prayas and

CSLG-JNU, 2007). Tariff is an instrument that

pertains to cost implications on water users and

distribution of the cost burden among the water

users. MWRRA is an independent regulatory

agency entrusted to make decisions on

distribution of these costs and benefits. Hence,

even the minor looking procedural lessons such

as publication of consultation documents in

local language or publishing a comprehensive

reasoned report, gains tremendous importance.

It is in these apparently small looking

procedural lacunas that the larger goal of

gaining legitimacy through procedural

robustness starts losing grounds in the minds of

the stakeholders and the public at large. It is

important to note that MWRRA was responsive

and not totally dismissive to the major demands

made related to enhancing the transparency,

accountability and participationthe three

pillars of procedural robustnessin the tariff

process. The stakeholder group that came

together in form of a loose civil society

coalition played an important role in opening

the spaces of public participation. This is an

important lesson in itself in all future regulatory

processes.

But there is another picture that can be

seen from looking at the broader implications of

the participatory process. The enhanced public

participation provided the grounds-view of the

various social and environmental aspects of

water tariff. It led to making the tariff system

more socially sensitive by ensuring

incorporation of several social criteria in tariff

determination. The overall cost burden on

agriculture, industry and domestic sectors was

also fixed in a way so that the prevalent crosssubsidy regime remains undisturbed. However,

these social-sensitization remained limited to

provision of concessions and did not translate

into the broader demand for basing the tariff on

the criteria of ensuring right to water for life and

livelihoods.

Another vital lesson to draw is that

MWRRA and the public at large lost an

important opportunity to ensure stronger

regulatory purview on financial aspects of

project development, management and

maintenance in water sector. This is the area

that forms the core of sectoral regulation and it

also forms the source of most of the

malpractices, irregularities, corruption and

inefficiencies that cripple the performance of

water sector today. Unfortunately this crucial

and most important dimension of regulation

remained untouched in the process conducted

Maharashtra Water Tariff Story

39

by MWRRA. Was this issue sidelined due to the

heavy focus on socially-relevant concessions?

Was it to be like this by the very design of the

tariff provisions in the MWRRA Act? Or was it

that the MWRRA was not ready to make any

such moves which will disturb the longestablished interests and networks within the

water bureaucracy and politics? More study is

needed to understand the real causes. But it is

clear from the analysis presented that there

were adequate grounds, especially based on the

argument for physical efficiency, to bring

financial aspects of projects under regulatory

purview of MWRRA. This shows how certain

crucial issues such as regulation of costs and

other financial aspects can go unaddressed,

especially when the debate on concessions

and subsidies get centre-staged. Financial

inefficiencies and irregularities will have

implications on the quality of infrastructure and

this in turn will affect the sustainability of

projects. If the public infrastructure fails it is the

disadvantaged sections of the society that will

be most affected, thus making the socialconcessions useless. Hence, regulating the

financial and costs related aspects of water

project/ service is the foundation on which all

other aspects of regulation can be built. Hence,

this area of regulation needs to be given equal

importance, if not more.

There are several instances, apart from

cost & financial regulation, where regulatory

mechanisms remained weak. More specifically

the regulatory process failed to deliver stronger

and effective regulatory mechanisms for

pollution control, water losses, water pilferagetheft, and wasteful use of water. Why does such

an elaborate and participatory process

supplemented by professional consultants does

not deliver on such crucial aspects? One

important lesson that can be drawn in this

40

Maharashtra Water Tariff Story

regard is about the logical flow and consistency

in the process of designing regulations.

MWRRA started with a positive note by

allowing stakeholders to comment on the ToR

for consultancy assignment. The public

consultation was also initiated on the basis of an

approach paper and not on the basis of any

fixed proposed design of regulations. An

approach paper will provide more space for the

public to comment and suggest alternative

approaches and principles to be adopted before

going into the specifics. Thus, it opens more

spaces for thinking on alternative ways to

address the problem and also can allow

focussing on the principles or normative

concerns to address the problem. Starting a

consultation process with this thinking will

certainly allow a smooth and logically correct

flow of discussion and design of regulations.

The beginning of the tariff process

conducted by MWRRA seemed to be heading

in the correct direction. But it was not so. The

first draft approach paper prepared by the

Consultant was not really an approach paper.

It had a very short discussion on principles and

normative aspects of water tariff. Leaving aside

the discussion on the overall approach and

principle, the approach paper directly proposed

a concrete methodology for tariff determination

based on its cost-apportionment model. It

should be noted that the same cost

apportionment methodology was used till the

end of the consultation and also accepted in the

final criteria with some minor changes. Thus,

the whole consultation process along with

MWRRAs thinking was fixated to the costapportionment model and later on the

concessions to certain sections of water users.

The approach paper, which was supposed to be

actually giving rise to several methodological

options to be assessed, itself provided one

specific method that sealed the boundary of

discussion in the consultation process. It

became a fate-accompali. What is interesting to

note is that the approach paper was totally silent

on the crucial aspect of regulating financial and

cost related aspects of water projects and

services. Thus, the various rounds of

consultations did not bring any major structural

change in the light-handed regulation (on

governmental affairs of publicly-managed

water utility) assumed in the first approach

paper on all the crucial aspects of water tariff.

This probably explains the failure of this

process to deliver strong and effective

regulatory mechanisms on critical issues such

as costs, operations, water losses, pilferagethefts, water-use efficiency, pollution control

and other aspects.

These are some of the vital lessons to be

drawn from the first-ever regulatory process in

tariff. Independent regulators such as MWRRA

work in a very complex and challenging

governance and regulatory space. Although

such regulatory models are now well

operationalized in electricity sector, water is a

completely different terrain. Constraints and

compulsions arising from mainstream politics

in water sector are far intense than in any other

sector. But ways and mechanisms have to be

developed to overcome these constraints and

compulsions. Intense public participation for

regulatory design is one such way forward. The

initial experience related to water tariff is

encouraging in this direction. But the process is

constrained by the limitations of the larger

normative and governance framework in form

of the legal provisions. The participatory

regulatory design should begin at its source, i.e.

right at the level of the policy and law

formulation. An open, transparent,

participatory process of independent regulation

coupled with a legally coded pro-people and

pro-poor normative framework may provide a

new avenue of strengthening and protecting

public interest in water sector.

Maharashtra Water Tariff Story

41

S-ar putea să vă placă și

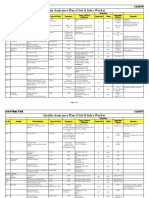

- Quality Assurance Plan - CivilDocument11 paginiQuality Assurance Plan - CivilDeviPrasadNathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stakeholder CommunicationDocument19 paginiStakeholder CommunicationMohola Tebello Griffith100% (1)

- 2002 CT Saturation and Polarity TestDocument11 pagini2002 CT Saturation and Polarity Testhashmishahbaz672100% (1)

- Cognitive Coaching AdelaideDocument3 paginiCognitive Coaching AdelaideBusiness-Edu100% (2)

- Water Resources Systems Planning and ManagementDocument10 paginiWater Resources Systems Planning and ManagementChandra MouliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Administration: Key Issues Challenging PractitionersDe la EverandPublic Administration: Key Issues Challenging PractitionersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Information Security Master PlanDocument6 paginiInformation Security Master PlanMarubadi Rudra Shylesh Kumar100% (2)

- Integrated Water Resources ManagementDocument44 paginiIntegrated Water Resources ManagementMuhammad HannanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Water Resources Management: Module - 3Document9 paginiIntegrated Water Resources Management: Module - 3Suhas.V Suhas.VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Resource Management PDFDocument47 paginiWater Resource Management PDFvandah7480Încă nu există evaluări

- Exam Ref 70 483 Programming in C by Wouter de Kort PDFDocument2 paginiExam Ref 70 483 Programming in C by Wouter de Kort PDFPhilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution of Management AccountingDocument35 paginiEvolution of Management AccountingNuqiah Fathiah Seri100% (1)

- Project Report On HeritageDocument39 paginiProject Report On HeritageBALA YOGESH YANDAMURIÎncă nu există evaluări

- GWP - Social Equity and Integrated Water Resources Management - 2011Document88 paginiGWP - Social Equity and Integrated Water Resources Management - 2011nicolasbujakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Individuals Make Decisions and They Mobilize and Manage ResourcesDocument5 paginiIndividuals Make Decisions and They Mobilize and Manage Resourcesferhan loveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Allocation MethodsDocument43 paginiWater Allocation MethodsGabriel VeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iisa PaperDocument13 paginiIisa PaperSanatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability 12 06327Document18 paginiSustainability 12 06327Umar DiwarmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Negotiating Water Rights in Contexts of Legal Pluralism: Priorities For Research and ActionDocument19 paginiNegotiating Water Rights in Contexts of Legal Pluralism: Priorities For Research and ActiontolandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSS For Equatable Water SharingDocument12 paginiDSS For Equatable Water SharingSudharsananPRSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Efficient Water AllocationDocument52 paginiEfficient Water AllocationEnoch ArdenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conclusions and Directions For Future Research: RD THDocument4 paginiConclusions and Directions For Future Research: RD THjohn_himaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comments On Water Policy 2012Document4 paginiComments On Water Policy 2012ManthanShripadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFDocument22 paginiAddressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFGino MontenegroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final - RetallackDocument14 paginiFinal - RetallackMachubuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conflict Resolution Benchmarking Water UDocument15 paginiConflict Resolution Benchmarking Water UlealÎncă nu există evaluări

- Participatory Irrigation ManagementDocument4 paginiParticipatory Irrigation ManagementIndependent Evaluation at Asian Development BankÎncă nu există evaluări

- Singapore and Sydney Regulation and Market-MakingDocument16 paginiSingapore and Sydney Regulation and Market-MakingAbhishekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Downstream of Irrigation Water PricingDocument20 paginiDownstream of Irrigation Water Pricingquestiones11Încă nu există evaluări

- PRAYAS Wagle Warghade Paper IRA Sawas Web PublishedDocument30 paginiPRAYAS Wagle Warghade Paper IRA Sawas Web PublishedSachin WarghadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q3Document3 paginiQ3haikal MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 Book GlobalizedWater-1Document303 pagini2014 Book GlobalizedWater-1Daniel NaroditskyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Water Management - 2-1Document37 paginiSmart Water Management - 2-1Vishal S SonuneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Value Is NothingDocument34 paginiThe Value Is NothingAslam SaifiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Uttar Pradesh Water Management and Regulatory CommissionDocument16 paginiAnalysis of Uttar Pradesh Water Management and Regulatory CommissionSachin WarghadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Aid Sustainability FrameworkDocument4 paginiWater Aid Sustainability FrameworkkaksalampayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water ModeelingDocument36 paginiWater ModeelingNtakirutimana ManasséÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Conference Full Report 0Document32 paginiWater Conference Full Report 0rentingh100% (1)

- Evaluation of An Integrated Asset Life-Cycle ManagDocument7 paginiEvaluation of An Integrated Asset Life-Cycle ManagbilalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exsum Water PolicyDocument2 paginiExsum Water PolicyImam EffendiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning in WRE ManagementDocument28 paginiPlanning in WRE ManagementHerman Buenaflor BibonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The River Chief System and River Pollution Control in China: A Case Study of FoshanDocument14 paginiThe River Chief System and River Pollution Control in China: A Case Study of FoshanBilly LadasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decentralised Governance 1110 eDocument4 paginiDecentralised Governance 1110 eMun VongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter VIDocument5 paginiChapter VISatadru Chakraborty KashyapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tariff Structures For Water and Sanitation Urban Households: A PrimerDocument19 paginiTariff Structures For Water and Sanitation Urban Households: A PrimerEzhilarasi BhaskaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Pricing - Potential and ProblemsDocument4 paginiWater Pricing - Potential and ProblemsVANISHA SINGHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uts Amdal RajivDocument15 paginiUts Amdal RajivrajivÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natural Resource Governance: New Frontiers in Transparency and AccountabilityDocument69 paginiNatural Resource Governance: New Frontiers in Transparency and Accountabilitymahdi sanaeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decentralized Water SolutionDocument22 paginiDecentralized Water SolutionPaulineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utilities Regulation in GhanaDocument25 paginiUtilities Regulation in GhanaAshwin RaparthiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Participatory Policy, AudreyDocument2 paginiParticipatory Policy, AudreyRamanujam RajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social AlternativesDocument53 paginiSocial AlternativesfungedoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Issues and Challenges in Water Governance in MalaysiaDocument10 paginiReview Issues and Challenges in Water Governance in MalaysiaAshvitha SegaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of Price and Enforcement in Water Allocation: Insights From Game TheoryDocument16 paginiRole of Price and Enforcement in Water Allocation: Insights From Game Theorylawakhamid1Încă nu există evaluări

- Water Law ProjectDocument48 paginiWater Law ProjectSurabhi ChaturvediÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Theories of Government: (CITATION Ele14 /L 1033)Document2 paginiThe Theories of Government: (CITATION Ele14 /L 1033)Amaan KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- NPTEL - Civil Engineering - Water Resources Systems Planning and ManagementDocument4 paginiNPTEL - Civil Engineering - Water Resources Systems Planning and ManagementMohitTripathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iwrm GWPDocument4 paginiIwrm GWPCacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENP23806 Sofia Van SettenDocument9 paginiENP23806 Sofia Van SettenSofia van SettenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 8Document6 paginiChapter 8Mesfin Mamo HaileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water InternationalDocument10 paginiWater Internationalirina_madalina2000Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2Document16 paginiChapter 2Mesfin Mamo HaileÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dublin Principles Revisited For WSSDocument4 paginiThe Dublin Principles Revisited For WSSyogaprasetyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability in A Failed State: Ben Taylor Rachel Lock Derek OakleyDocument5 paginiSustainability in A Failed State: Ben Taylor Rachel Lock Derek OakleyFarai MandisodzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Paradigms of Sustainability in the Contemporary EraDe la EverandNew Paradigms of Sustainability in the Contemporary EraRoopali SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- African TallDocument4 paginiAfrican TallMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation - TISS - v2Document28 paginiPresentation - TISS - v2Mandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- NWP 20025617515534Document10 paginiNWP 20025617515534pradipkbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Background Note On DirectivesDocument6 paginiBackground Note On DirectivesMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploiting Policy Obscurity For Legalising Water Grabbing in The Era of Economic Reform: The Case of Maharashtra, IndiaDocument19 paginiExploiting Policy Obscurity For Legalising Water Grabbing in The Era of Economic Reform: The Case of Maharashtra, IndiaMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visit To Water BankDocument26 paginiVisit To Water BankMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sachin Tendulkar's CVDocument3 paginiSachin Tendulkar's CVhemant117100% (1)

- Visit To Water BankDocument26 paginiVisit To Water BankMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rural Drinking Water 2ndApril-SoftDocument120 paginiRural Drinking Water 2ndApril-SoftMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hydro Power PolicyDocument20 paginiHydro Power PolicyMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arjun SenguptaDocument4 paginiArjun SenguptaMandar Vaman SatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Determination of Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in Honey Using The LAMBDA SpectrophotometerDocument3 paginiDetermination of Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in Honey Using The LAMBDA SpectrophotometerVeronica DrgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bsa2105 FS2021 Vat Da22412Document7 paginiBsa2105 FS2021 Vat Da22412ela kikayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Passive Income System 2Document2 paginiPassive Income System 2Antonio SyamsuriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Direct and Indirect Pulp CappingDocument9 paginiJurnal Direct and Indirect Pulp Cappingninis anisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Intermediate 2 Workbook AnswerDocument23 paginiHigh Intermediate 2 Workbook AnswernikwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Case Analysis-Team ProjectDocument5 paginiSupreme Court Case Analysis-Team ProjectJasmineA.RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rfis On Formliners, Cover, and EmbedmentsDocument36 paginiRfis On Formliners, Cover, and Embedmentsali tahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Technological UniversityDocument3 paginiDr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Technological UniversityalfajÎncă nu există evaluări

- SST Vs BBTDocument7 paginiSST Vs BBTFlaxkikare100% (1)

- Growth Kinetic Models For Microalgae Cultivation A ReviewDocument16 paginiGrowth Kinetic Models For Microalgae Cultivation A ReviewJesús Eduardo De la CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electronic Waste Management in Sri Lanka Performance and Environmental Aiudit Report 1 EDocument41 paginiElectronic Waste Management in Sri Lanka Performance and Environmental Aiudit Report 1 ESupun KahawaththaÎncă nu există evaluări

- NHD Process PaperDocument2 paginiNHD Process Paperapi-122116050Încă nu există evaluări

- 3114 Entrance-Door-Sensor 10 18 18Document5 pagini3114 Entrance-Door-Sensor 10 18 18Hamilton Amilcar MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enzymes WorksheetDocument5 paginiEnzymes WorksheetgyunimÎncă nu există evaluări

- GSP AllDocument8 paginiGSP AllAleksandar DjordjevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student Committee Sma Al Abidin Bilingual Boarding School: I. BackgroundDocument5 paginiStudent Committee Sma Al Abidin Bilingual Boarding School: I. BackgroundAzizah Bilqis ArroyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship (1) FinalDocument12 paginiInternship (1) FinalManak Jain50% (2)

- Unix SapDocument4 paginiUnix SapsatyavaninaiduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Paper Book StandardDocument24 paginiSample Paper Book StandardArpana GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Evolution of Knowledge Management Systems Needs To Be ManagedDocument14 paginiThe Evolution of Knowledge Management Systems Needs To Be ManagedhenaediÎncă nu există evaluări

- C7.5 Lecture 18: The Schwarzschild Solution 5: Black Holes, White Holes, WormholesDocument13 paginiC7.5 Lecture 18: The Schwarzschild Solution 5: Black Holes, White Holes, WormholesBhat SaqibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement On Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument5 paginiThesis Statement On Corporate Social Responsibilitypjrozhiig100% (2)

- Curriculum Policy in IndonesiaDocument23 paginiCurriculum Policy in IndonesiaEma MardiahÎncă nu există evaluări