Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Nestorius Heretic or Harassed - Libre

Încărcat de

Allan AraujoTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Nestorius Heretic or Harassed - Libre

Încărcat de

Allan AraujoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Nestorius: Heretic or Harassed?

A Reexamination

of the Evidence in light of the Bazaar of Heracleides

David C. Strobolakos

trewn across the history of the Church lay heretics anathematized

by conciliar pronouncement. From the first ecumenical council of

Nicaea to the second, Church leaders heatedly defined and

defended orthodox theology in attempts to preserve Apostolic kerygma

for future generations. No stranger to the history of these councils is the

theology of the once Bishop of Constantinople: Nestorius. Since the

time of his condemnation at the Council of Ephesus (AD 431) Nestorius

and his namesake heresy Nestorianism have become a beleaguered

ecclesiastical anecdote illustrating the power of conciliar decree.

However, the 19th century discovery of Nestorius work The Bazaar of

Heracleides sparked a renewed interest in this infamous heretic and

subsequent inquiry has cast doubt over the legitimacy of Nestorius

condemnation. 1 Could it be that Nestorius actually never believed or

taught Nestorianism? Could Nestorius claims actually more

authentically reflect the biblical data as opposed to the widely accepted

Alexandrian Christology? Was Nestorius merely the unfortunate

interlocutor for a scheming politician named Cyril?2 In response to the

conventional replies to these questions, another look at the evidence will

prove that Nestorius cannot be substantively accused of postulating a

distinctly Nestorian Christology.

Definitions

For the purposes of this essay, several terms need particular care given to

them. First, and most importantly, is the term . In the Bazaar,

Nestorius uses this term to denote the totality of essential attributes that

compose a nature.3 For example, each individual person has a particular

1

For an overview of 20th scholarship on Nestorius post-discovery of The

Bazaar see: Carl E. Braaten, Modern Interpretations of Nestorius, Church History 32,

no. 3 (September 1963): 251-267.

2

Richard Kyle, Nestorius: The Partial Rehabilitation of a Heretic, Journal of

the Evangelical Theological Society 32, no. 1 (March 1989): 78.

. Each individual animal has a particular , etc. To

take anything away from this totality of attributes would degrade the

nature in question, leaving the subject lacking essential qualities.

Nestorius understood this term to be fundamentally synonymous with

his opponent Cyrils term . In doing so, he followed the tradition of

Nicaea and the general understanding of the Greek-speaking world.4

The second term needing definition is proswpon. For Nestorius,

proswpon refers to the person as regarded from the outside.5 Situated

in a Christological setting, Nestorius believed Christs proswpon united

the two (divine and human) into one visible countenance,

providing for the interplay between the human and divine. This is

perhaps better understood as the dynamic equivalent of the Alexandrian

communicatio idiomatum. 6 Nestorius was clear that it was only through

positing this common proswpon that both the human and divine

natures of Christ would be preserved unaltered.7

Nestorius Speaks

Nestorius primary opponent at the Council of Ephesus was Cyril of

Alexandria. During council proceedings, Cyril levied twelve anathemas

against Nestorius concerning his Christological construction. 8

Subsequently, Nestorius spends a great deal of time in the Bazaar

responding to Cyrils accusations and attempting to vindicate his

position. His approach centers on the specific point where Cyril takes

issue with his Christology: the nature of the union between the human

and divine elements.

Nestorius has no problem agreeing with Cyril that God and man

were both present in Jesus Christ. Indeed he claims, I have said that the

name Christ is indicative of two natures, of God indeed one nature [and

3

George Kalantzis, Is There Room for Two? Cyrils Single Subjectivity and

the Prosopic Union, St. Vladimirs Theological Quarterly 52, no. 1 (2008): 98.

4

Milton V. Anastos, Nestorius Was Orthodox, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 32

(1962): 125; J.F. Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching: A Fresh Examination of the

Evidence (1908; repr., New York: Kraus Reprint Co., 1969), 47.

5

Nestorius, The Bazaar of Heracleides, trans. and eds. G. R. Driver and L.

Hodgson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925), 402.

6

Kalantzis, 100.

7

Anastos, 126.

8

John McGuckin, St. Cyril of Alexandria: The Christological Controversy

(Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimirs Seminary Press, 2004), 273-275.

of man one nature].9 Their disagreement arises over the nuances of the

union. Cyril argues that the union occurs in the essentially a

human nature/substance fully intertwined with the Divine

nature/substance. Nestorius, on the other hand, maintains a union

through the proswpon.10 Perhaps a helpful analogy for this is that of a

figure skating team gliding over the ice in perfect rhythm even hardly

distinguishable from one other. They form a singular, dynamic presence

on the ice and work together to accomplish a successful routine.

Although this illustration is not perfect, it serves to illustrate the

underpinnings of Nestorius Christology; namely, two persons appearing

as one. Nestorius prefers this type of Christological construction because

he believes it preserves the orthodox understanding of Christs full

divinity and full humanity.

Nestorius was keenly aware of the danger of reducing the

incarnation to inadequate terms. Subsequently, one of his primary goals

was to circumvent any possible misunderstanding regarding the union of

deity and humanity in Christ. He could not square with Apollinaris who

had denied that Christ possessed a human soul, but he also could not

accept the adoptionistic presuppositions of Paul of Samosata who saw

the incarnation as nothing more than human assumption.11 Conversely,

Nestorius fundamentally believed that the proswpon of Christ

contained two complete and distinct . 12 Most importantly,

each of these retained their essential qualities as they

conjoined in the human/divine union.13

For Nestorius, Cyrils construction of the incarnation, although

attempting to account for the two natures, does absolute injustice to the

reality of two complete elements present in Jesus Christ. 14 He says,

they predicate a change of natures by union, attributing nothing either

to the humanity or to the divinity in making over the things of humanity

to the nature and those of the divinity to the nature. 15 Therefore,

neither the Godhead nor the manhood retains their particular qualities.

In Nestorius mind, this type of union could not help but form a sort of

tertium quid; neither nature any longer exhibiting distinct characteristics.

9

Nestorius, 209.

10

Nestorius, 157.

11

Thomas Weinandy, Does God Change? (Still River, Mass.: St. Bedes

Publications, 1985), 25.

12

Nestorius, 217-218.

13

Nestorius, 145-146.

14

Nestorius, 155-156.

15

Nestorius, 94.

With that being said, Nestorius does not go as far as saying that these two

natures are distant and divided from each other.16 Although they are

distinct natures they operate as one being, united through their common

proswpon.

In making these claims, Nestorius believed he was directly in line

with orthodox theology. He even desperately appeals to widely respected

church fathers Ambrose and Athanasius to ground his claims, arguing

that he says the very same things they do. 17 Needless to say, his

condemnation took him by surprise and he was left wondering exactly

where he went wrong.18 He makes his final petition in the Bazaar of

Heracleides as a last attempt to clear his name and propose his true

thoughts in favor of what he believes to be safely within the bounds of

orthodoxy.

Scholars Speak

Ever since the recent discovery and circulation of the Bazaar of Heraclides,

many scholars have renewed their interest in reexamining what Nestorius

actually taught. Subsequent findings have fallen at various places on the

spectrum of orthodoxy. While some remain committed to the traditional

condemnation of Nestorius, others seek to portray a different picture of

him a more positive picture. A variety of factors play into these

scholars final assessments of Nestorius including an examination of his

metaphysics, prodding his definitions, and questioning the clarity of his

presentation.

Completely Unorthodox

H.A. Wolfson believes a traditional, heretical read of Nestorius to be the

most plausible assessment. Wolfson contends that Nestorius fails to fall

in line with orthodoxy based on his metaphysical understanding of the

incarnation. He understands Nestorius to hold that, prior to the

incarnation, both the Divine and human elements of Christ were two

complete persons.19 As such, they each possessed the complete set of

qualities required to define them as a person; namely, a and a

16

Nestorius, 233.

17

Nestorius, 261.

18

Nestorius, 95; 145.

19

H. A. Wolfson, The Philosophy of the Church Fathers, vl. 1 (Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 1956), 454.

proswpon. Subsequently, when these two persons conjoined in the

incarnation, neither of them lost any of their essential attributes.20

With this, Wolfson understands Nestorius to depart from standard

orthodoxy. For the orthodox fathers of the church, the incarnation

consisted of a complete Divine person ( and proswpon)

conjoined only with a human . Otherwise understood as two

natures within one person. Because Wolfson believes that Nestorius

never departs from what appears to be a mere juxtaposition of two

complete persons within Christ, he remains unconvinced that Nestorius

should be properly understood as orthodox.21

Completely Unsure

Nevertheless, there are those who take a more charitable read of

Nestorius in light of the Bazaar. Richard Kyle assesses Nestorius claims

and agrees with some of Wolfsons statements. Nestorius did argue for

the presence of two complete persons in the incarnation. 22 He did

believe their natures to be distinct and in no way compromised in the

Divine/human conjunction.23 However, Kyle denies Wolfsons ultimate

conclusion that Nestorius divides Christ into two persons conjoined only

through juxtaposition. 24 Kyle understands Nestorius to posit a much

more intimate connection between the two persons. In fact, the two

persons are so conjoined that they display themselves to the world

through a single, common proswpon not two separate ones.25 He claims

that Nestorius could not fathom the idea of complete duality in

sonship.26

In light of this, Kyle argues that Nestorius censure came primarily

because of his poor use of language; particularly his use of proswpon.

Because Nestorius was somewhat careless in defining his use of this term,

a cloud of unnecessary confusion arose that might have been

circumvented and avoided his condemnation.27 Ultimately, Kyle believes

that Measured by what he said in the BazaarNestorius was not

Nestorian: He did not split Jesus Christ into two persons, the divine and

20

Wolfson, 455.

21

Wolfson, 462.

22

Kyle, 79.

23

Kyle, 79.

24

Kyle, 81.

25

Kyle, 79.

26

Kyle, 79.

27

Kyle, 80.

the human, loosely connected. 28 Kyle makes it clear that this

assessment, however, does not apply to Nestorius earlier life, where he

may have held to traditional Nestorian tenets, but to his final

Christological understanding as evidenced in the Bazaar. 29 So, while

Nestorius was probably not Nestorian at the end of his life, there is no

absolute way to prove he was not at the beginning of his episcopate.

Completely Orthodox

Additionally, there are scholars who disagree with both Wolfson and

Kyle arguing that Nestorius was actually completely orthodox in

persuasion. J.F. Bethune-Baker stands at the forefront of this group for a

peculiar reason. In fact, Bethune-Baker originally held to the belief that

Nestorius was completely unorthodox.30 However, after reading through

the Bazaar, he changed his mind saying, Nestorius did not hold the

belief commonly attributed to him that in Jesus Christ two persons, the

person of God and the person of man, were mechanically joined

together31 How then does Bethune-Baker assess the same evidence

and arrive at this alternative conclusion?

Bethune-Baker observes Nestorius repeatedly argue for the

singular personhood of Jesus Christ.32 Inherent to that person are two

distinct substances: one of God and one of man. However, in spite of the

union occurring, there was no mixing or comingling of either

substance so that they lost their otherness. 33 Bethune-Baker believes

Nestorius is adamant about this because he thought, any view of the

Incarnation which does not recognize the continued existence of the ousia

[] of the human nature is not a real incarnation.34 In short,

full humanity must be preserved in order for full redemption to occur.

The difficulty arises when Nestorius starts using terms like

conjunction to describe the relationship between the Godhead and the

manhood. With terms like these, it appears that he posits merely a

collaboration of two separate substances in the incarnation without any

28

Kyle, 81.

29

Kyle, 82.

30

See: J. F. Bethune Baker, An Introduction to the Early History of Christian

Doctrine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1903).

31

Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching, 82.

32

Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching, 84.

33

Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching, 87.

34

Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching, 96.

real cohesion of sorts. However, Bethune-Baker argues that this is not

the case. Nestorius actually intends to communicate something more

along the lines of cohesion when using this term. 35 Therefore, the

incarnation consists of two intimately conjoined in the Godman Jesus Christ; a relationship going much further than simple

collaboration.

So, Nestorius posits two complete substances in the incarnation to

retain the elements necessary for redemption and uses specific terms to

rule out any confusion concerning the way these elements combine in

Jesus Christ. With these considerations in mind, Bethune-Baker

concludes, Reading his own words, carefully and consecutively, as we

can read them now, it is impossible to believe that Nestorius was

Nestorian.36

Conclusion

Despite even the best intentions, decisions are made at times with biased

presuppositions and hasty judgments. Given the evidence, it appears that

this may be what happened with the decision against Nestorius at the

Council of Ephesus (AD 431). With careful analysis of Nestorius

theological presuppositions and his use of particular terminology, it

cannot be conclusively determined that he held to an essentially

unorthodox Christological formulation. At best, he can be accused of

speaking unclearly and thereby producing confusion in the minds of the

other bishops who condemned him. Truly, the discovery of The Bazaar of

Heracleides has greatly assisted in the effort to exonerate Nestorius from

false accusations and vindicate his name for further generations. With

this new tool in hand, scholarship presses on to further discover the

nuances of Nestorius argument in order to hear him on his own terms

and judge him accordingly.

35

Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching, 90.

36

Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching, 198.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- One of a Kind: The Relationship between Old and New Covenants as the Hermeneutical Key for Christian Theology of ReligionsDe la EverandOne of a Kind: The Relationship between Old and New Covenants as the Hermeneutical Key for Christian Theology of ReligionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Being Salvation: Atonement and Soteriology in the Theology of Karl RahnerDe la EverandBeing Salvation: Atonement and Soteriology in the Theology of Karl RahnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Reassessment of Cyril of Alexandria's Christology: A Relational PerspectiveDocument19 paginiThe Reassessment of Cyril of Alexandria's Christology: A Relational PerspectiveTimothy Lam100% (1)

- Nestorius and His Place in the History of Christian DoctrineDe la EverandNestorius and His Place in the History of Christian DoctrineÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Nicaea to Chalecdon: A Guide to the Literature and Its BackgroundDe la EverandFrom Nicaea to Chalecdon: A Guide to the Literature and Its BackgroundEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Augustine and Nicene Theology: Essays on Augustine and the Latin Argument for NicaeaDe la EverandAugustine and Nicene Theology: Essays on Augustine and the Latin Argument for NicaeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vincent of Lérins and the Development of Christian Doctrine ()De la EverandVincent of Lérins and the Development of Christian Doctrine ()Încă nu există evaluări

- Crucified and Resurrected: Restructuring the Grammar of ChristologyDe la EverandCrucified and Resurrected: Restructuring the Grammar of ChristologyEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- Truth Is Symphonic: Aspects of Christian PluralismDe la EverandTruth Is Symphonic: Aspects of Christian PluralismEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- As It Is in Heaven: Some Christian Questions on the Nature of ParadiseDe la EverandAs It Is in Heaven: Some Christian Questions on the Nature of ParadiseÎncă nu există evaluări

- For the Unity of All: Contributions to the Theological Dialogue between East and WestDe la EverandFor the Unity of All: Contributions to the Theological Dialogue between East and WestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Person, Personhood, and the Humanity of Christ: Christocentric Anthropology and Ethics in Thomas F. TorranceDe la EverandPerson, Personhood, and the Humanity of Christ: Christocentric Anthropology and Ethics in Thomas F. TorranceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mutual Hierarchy: A New Approach to Social TrinitarianismDe la EverandMutual Hierarchy: A New Approach to Social TrinitarianismÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology: Evangelical Catholicism in the Mid-Nineteenth CenturyDe la EverandA Companion to the Mercersburg Theology: Evangelical Catholicism in the Mid-Nineteenth CenturyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Early Creeds: The Mercersburg Theologians Appropriate the Creedal HeritageDe la EverandThe Early Creeds: The Mercersburg Theologians Appropriate the Creedal HeritageÎncă nu există evaluări

- Divine Simplicity: A Biblical and Trinitarian Account: A Biblical and Trinitarian AccountDe la EverandDivine Simplicity: A Biblical and Trinitarian Account: A Biblical and Trinitarian AccountÎncă nu există evaluări

- Illumination in Basil of Caesarea's Doctrine of the Holy SpiritDe la EverandIllumination in Basil of Caesarea's Doctrine of the Holy SpiritEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Transformed in Christ: Christology and the Christian Life in John ChrysostomDe la EverandTransformed in Christ: Christology and the Christian Life in John ChrysostomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dogmatic Aesthetics: A Theology of Beauty in Dialogue with Robert W. JensonDe la EverandDogmatic Aesthetics: A Theology of Beauty in Dialogue with Robert W. JensonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reformed Epistemology and the Problem of Religious Diversity: Proper Function, Epistemic Disagreement, and Christian ExclusivismDe la EverandReformed Epistemology and the Problem of Religious Diversity: Proper Function, Epistemic Disagreement, and Christian ExclusivismÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Concept of Nature in the Thought of John Philoponus And Other EssaysDe la EverandThe Concept of Nature in the Thought of John Philoponus And Other EssaysÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Patristic Understanding of Creation: An Anthology of Writings from the Church Fathers on Creation and DesignDe la EverandThe Patristic Understanding of Creation: An Anthology of Writings from the Church Fathers on Creation and DesignÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traditions of Exegesis - Frances M. Young PDFDocument18 paginiTraditions of Exegesis - Frances M. Young PDFPricopi VictorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ever-Moving Repose: A Contemporary Reading of Maximus the Confessor’s Theory of TimeDe la EverandEver-Moving Repose: A Contemporary Reading of Maximus the Confessor’s Theory of TimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Receiving 2 Thessalonians: Theological Reception Aesthetics from the Early Church to the ReformationDe la EverandReceiving 2 Thessalonians: Theological Reception Aesthetics from the Early Church to the ReformationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian DoctrineDe la EverandRetrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian DoctrineEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- Engaging Ecclesiology: Papers from the Edinburgh Dogmatics Conference 2021De la EverandEngaging Ecclesiology: Papers from the Edinburgh Dogmatics Conference 2021Încă nu există evaluări

- Cosmology Without God?: The Problematic Theology Inherent in Modern CosmologyDe la EverandCosmology Without God?: The Problematic Theology Inherent in Modern CosmologyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Embodied Words, Spoken Signs: Sacramentality and the Word in Rahner and ChauvetDe la EverandEmbodied Words, Spoken Signs: Sacramentality and the Word in Rahner and ChauvetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richard of Saint Victor, On the Trinity: English Translation and CommentaryDe la EverandRichard of Saint Victor, On the Trinity: English Translation and CommentaryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recognizing the Gift: Toward a Renewed Theology of Nature and GraceDe la EverandRecognizing the Gift: Toward a Renewed Theology of Nature and GraceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Birth of Modern Belief: Faith and Judgment from the Middle Ages to the EnlightenmentDe la EverandThe Birth of Modern Belief: Faith and Judgment from the Middle Ages to the EnlightenmentEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (3)

- Doctrine and Power: Theological Controversy and Christian Leadership in the Later Roman EmpireDe la EverandDoctrine and Power: Theological Controversy and Christian Leadership in the Later Roman EmpireEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- Theological Authority in the Church: Reconsidering Traditionalism and HierarchyDe la EverandTheological Authority in the Church: Reconsidering Traditionalism and HierarchyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comments on Fr. Thomas White’s Essay (2019) "Thomism for the New Evangelization"De la EverandComments on Fr. Thomas White’s Essay (2019) "Thomism for the New Evangelization"Încă nu există evaluări

- Neoplatonist Stew: How Pagan Philosophy Corrupted Christian TheologyDe la EverandNeoplatonist Stew: How Pagan Philosophy Corrupted Christian TheologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient Apologetic Exegesis: Introducing and Recovering Theophilus’s WorldDe la EverandAncient Apologetic Exegesis: Introducing and Recovering Theophilus’s WorldÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Greek Thomist: Providence in Gennadios ScholariosDe la EverandA Greek Thomist: Providence in Gennadios ScholariosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Procession of the Holy Ghost from the Father and the SonDe la EverandThe Procession of the Holy Ghost from the Father and the SonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dominican Theology at the Crossroads: A Critical Editions and a Study of the Prologues to the Commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard by James of Metz and Hervaeus NatalisDe la EverandDominican Theology at the Crossroads: A Critical Editions and a Study of the Prologues to the Commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard by James of Metz and Hervaeus NatalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Evil, Providence, and Freedom: A New Reading of MolinaDe la EverandOn Evil, Providence, and Freedom: A New Reading of MolinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Law of the Eucharist: Radbertus vs. Ratramnus—Their Controversy as to the Nature of the EucharistDe la EverandThe Law of the Eucharist: Radbertus vs. Ratramnus—Their Controversy as to the Nature of the EucharistÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christ in Christian Tradition: Volume Two: Part ThreeDocument695 paginiChrist in Christian Tradition: Volume Two: Part Threejean nedeleaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swords and Plowshares: American Evangelicals on War, 1937–1973De la EverandSwords and Plowshares: American Evangelicals on War, 1937–1973Încă nu există evaluări

- An Essay on the Development of Christian DoctrineDe la EverandAn Essay on the Development of Christian DoctrineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusDe la EverandPostmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (3)

- Atonement and Violence: A Theological ConversationDe la EverandAtonement and Violence: A Theological ConversationEvaluare: 2.5 din 5 stele2.5/5 (3)

- Christ and Analogy: The Christocentric Metaphysics of Hans Urs von BalthasarDe la EverandChrist and Analogy: The Christocentric Metaphysics of Hans Urs von BalthasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Virgin-Birth of Our Lord A paper read (in substance) before the confraternity of the Holy Trinity at CambridgeDe la EverandThe Virgin-Birth of Our Lord A paper read (in substance) before the confraternity of the Holy Trinity at CambridgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 11 The Doctrine of Salvation PDFDocument25 paginiLecture 11 The Doctrine of Salvation PDFZebedee TaltalÎncă nu există evaluări

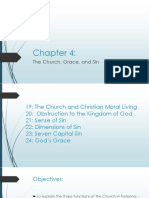

- Chapter 4 PDFDocument39 paginiChapter 4 PDFJohn Feil JimenezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter+4 Grade+10Document16 paginiChapter+4 Grade+10dǝʍdǝʍÎncă nu există evaluări

- Religion Finals: SacramentDocument17 paginiReligion Finals: SacramentMYKRISTIE JHO MENDEZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who and What Is The Holy Ghost?Document5 paginiWho and What Is The Holy Ghost?Friends of Max Skousen100% (2)

- Grade04 PriesthoodDocument24 paginiGrade04 PriesthoodForchia CutarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Marrow ControversyDocument45 paginiThe Marrow ControversyNick_MaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immaculate Conception Why Thomas Aquinas PDFDocument70 paginiImmaculate Conception Why Thomas Aquinas PDFAndrei DumitrescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alpha Course Is It Good For CatholicsDocument175 paginiAlpha Course Is It Good For CatholicsFrancis LoboÎncă nu există evaluări

- 30th October 2016 Parish BulletinDocument4 pagini30th October 2016 Parish BulletinourladyofpeaceparishÎncă nu există evaluări

- 35 Christian SectsDocument5 pagini35 Christian SectsMohammed Abdul KhaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Contribution of Congar's Theology of The Holy SpiritDocument28 paginiThe Contribution of Congar's Theology of The Holy SpiritAlvi Viadoy0% (1)

- Two Feet of Love, and Evangelization, in Action by Susan Stevenot SullivanDocument25 paginiTwo Feet of Love, and Evangelization, in Action by Susan Stevenot SullivanCCUSA_PSMÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Commandments: Our Blueprint For Moral LifeDocument9 paginiThe Commandments: Our Blueprint For Moral LifeRodelyn RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide For The Holy RosaryDocument1 paginăGuide For The Holy RosaryCharmaine JonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- SB057 - The DISPENSATION of GRACE PDFDocument5 paginiSB057 - The DISPENSATION of GRACE PDFRaftini100% (1)

- The Greatest MiracleDocument2 paginiThe Greatest MiracleCharles Walter AresonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 29 The Third CommandmentDocument11 pagini29 The Third CommandmentSaturday Doctrine ClassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amazing Grace: RefrainDocument2 paginiAmazing Grace: RefrainJohn Clifford MantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- What It Means To Surrender 100% To Jesus Christ.Document1 paginăWhat It Means To Surrender 100% To Jesus Christ.AndrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- One God, Why Many ChurchesDocument5 paginiOne God, Why Many ChurchesSamuel DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- EschatologyDocument2 paginiEschatologyraj_lopez9608Încă nu există evaluări

- Uriah SmithDocument2 paginiUriah SmithJayhia Malaga JarlegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Slaves of RighteousnessDocument8 paginiSlaves of RighteousnessKibet TuiyottÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Converts Complete Lessons Book 1Document31 paginiNew Converts Complete Lessons Book 1Michelle AnsahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feb 11Document1 paginăFeb 11matthewadanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ephesians CH 1 Pt1Document3 paginiEphesians CH 1 Pt1Jaesen XyrelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basis of The Catholic FaithDocument43 paginiBasis of The Catholic Faith爪フÎncă nu există evaluări

- Missionary Work Part 1 TimesDocument4 paginiMissionary Work Part 1 TimesTafadzwa KusangayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Become A ChristianDocument2 paginiHow To Become A ChristiandomomwambiÎncă nu există evaluări